Abstract

This paper explores the key professional and institutional factors that influence the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into financial evaluation and auditing processes. The study investigates the impact of legal familiarity, ESG experience, professional qualifications, and digital competencies on ESG readiness among financial analysts, auditors, and economists. By integrating a structured review of academic literature with an in-depth analysis of European regulatory instruments, the research identifies how dual materiality principles, standardized ESG metrics, and taxonomy-aligned disclosures reshape professional practices. A structured, ethics-approved survey (10 items) was administered nationally, and 145 responses were retained for analysis across economists, analysts, and auditors. Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, and linear/multiple regressions were used to test three hypotheses regarding ESG experience, legislative familiarity, and multifactor effects. The results reveal that familiarity with EU legislation is the strongest predictor of ESG integration capacity, while ESG-related experience and digitalization also show moderate to strong influence. The multiple regression model confirms the multifactorial nature of ESG implementation, though not all professional predictors contribute equally. Residual analysis confirms the statistical robustness of the models. The study highlights the need for regulatory literacy, targeted training, and digital adaptation as critical components of ESG competency.

1. Introduction

The transition from non-financial information to sustainability information within the European Union (EU) legislative framework introduces a paradigm shift in corporate reporting and the professional responsibilities of financial analysts and auditors. Sustainability reporting has evolved from a voluntary disclosure practice into a legally binding requirement in the European Union, redefining the responsibilities of financial analysts and auditors [1,2]. Also, sustainability reporting has become a central element in the global shift towards more responsible and transparent economic behaviour [3].

A pivotal element in this transition is Directive (EU) 2022/2464 [1], known as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) [4]. This directive officially replaces the term “non-financial information” with “sustainability information,” thereby indicating a more integrated and substantive approach to ESG disclosures. Under the CSRD, large enterprises and publicly listed companies (excluding micro-entities) are now mandated to report on both the influence of sustainability factors on their performance and their own impact on people and the environment [5].

Complementing this regulatory change, Regulation (EU) 2020/852 [2], commonly referred to as the Taxonomy Regulation, establishes a classification system to define environmentally sustainable economic activities. It codifies principles such as “substantial contribution” to environmental objectives, “do no significant harm” (DNSH), and adherence to minimum social safeguards, all aimed at enhancing the consistency, comparability, and credibility of ESG-related reporting [6,7].

These legislative initiatives aim to align corporate disclosures with the goals of the European Green Deal and facilitate the transition to a low-carbon economy. These legal innovations emphasize the principle of dual materiality, which involves two dimensions of reporting:

- The influence of sustainability-related risks and opportunities on a company’s financial outlook;

- The company’s direct impact on sustainability issues. This duality requires that financial analysts and auditors enhance their technical capabilities by integrating taxonomy-aligned disclosures and ESG metrics into traditional financial valuation, risk assessment, and assurance frameworks.

The shift from voluntary to regulated sustainability reporting is reshaping the role of financial professionals [8]. ESG indicators are no longer peripheral to financial reporting; instead, they are being institutionalized through binding regulations, digital reporting standards, and third-party verification requirements. The CSRD requires companies to report in accordance with the ESRS, obtain independent (limited) assurance, and digitally label sustainability data using the ESRS XBRL taxonomy [9]. Outside the EU, a growing number of jurisdictions are introducing IFRS S1/S2 on sustainability disclosure. For example, Australia has adopted mandatory climate-related financial disclosure with assurance provisions [10], and the climate rules of Taiwan and Singapore’s SGX include IFRS S2 requirements for listed issuers [11]. These developments necessitate a re-evaluation of the methodologies employed in economic analysis and auditing, particularly in the context of environmental investment decisions.

Financial evaluation and statutory auditing are designed to obtain reasonable assurance that financial statements present an accurate and fair view, based on sufficient appropriate evidence and grounded in professional judgment. When these principles are extended to sustainability disclosures, the assurance logic remains continuous. Still, the subject matter, criteria, and evidence shift toward non-financial dimensions, which reconfigure both professional preparedness and institutional oversight. ESG assurance, in continuity with traditional financial assurance, clarifies how established assurance objectives interact with emerging sustainability requirements and why professional and institutional determinants remain pivotal for credibility and comparability in practice [12].

The purpose of this paper is to examine the role of sustainability reporting in redefining the responsibilities of financial analysts and auditors, with particular emphasis on the implications of recent EU legislation. By conducting a structured review of relevant literature and regulatory documents, the study aims to clarify how sustainability information is produced, interpreted, and validated, as well as the impact of these processes on organizational performance and financial decision-making.

This study addresses the research problem of the gap between the expanding regulatory framework on sustainability reporting in the European Union and the degree of preparedness of financial professionals to integrate ESG indicators into financial evaluation and auditing practices. While the CSRD and the EU Taxonomy impose binding obligations, the actual ability of analysts, auditors, and economists to operationalize these requirements remains uneven. Accordingly, the study is guided by the following research question: How do professional qualifications, ESG-related experience, and digital competencies influence the integration of sustainability indicators into financial evaluation? This formulation establishes the link between regulatory expectations and professional adaptation, thereby framing the empirical analysis undertaken in the subsequent sections.

This research employs a mixed-methods exploratory design, combining a qualitative, document-based analysis of regulatory frameworks and literature with a quantitative survey that empirically assesses professional readiness for ESG integration. The methodological design reflects a document-based approach, with a dual focus: first, to identify the structural changes introduced by recent EU regulations, and second, to examine how these changes reshape the responsibilities of financial analysts and auditors in the context of environmental investment management.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the Materials and Methods, outlining the theoretical foundations of the study, the selection of key regulatory and professional frameworks, and the justification for the applicative research. Section 3 details the Research Methodology, including the formulation of research hypotheses, the operationalization of variables, and the use of statistical techniques. Section 4 presents the Results, highlighting the main empirical findings and the relationships identified between professional characteristics and ESG integration. Section 5 presents a Discussion of the results in relation to the conceptual framework and the EU regulatory context. Finally, Section 6 provides the Conclusions, summarizing the key contributions of the study, limitations, and proposing directions for future research.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Context

The institutionalization of ESG reporting can be understood through the interplay of institutional, stakeholder, and resource-based perspectives. Institutional theory highlights how regulatory frameworks, such as the EU’s CSRD, establish binding rules that redefine professional practices in accounting and auditing. Stakeholder theory emphasizes the pressures exerted by investors, regulators, and society to enhance the credibility and transparency of sustainability disclosures. At the same time, the resource-based view frames professional knowledge, ESG-related competencies, and technological capacities as critical resources that enable organizations to adapt to the evolving reporting landscape. Together, these perspectives provide a coherent theoretical foundation for analyzing the determinants of professional preparedness in ESG reporting [9].

The core normative references for this research are Directive (EU) 2022/2464, which formalizes the transition from non-financial to sustainability reporting, and Regulation (EU) 2020/852, which sets out a detailed taxonomy for sustainable activities. These documents were analysed in conjunction with technical materials and working papers issued by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) [13] and European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) [14].

In addition to the CSRD framework applicable in the European Union, sustainability disclosures are increasingly structured around the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards issued by the ISSB. IFRS S1 provides the general requirements for disclosure of sustainability-related financial information, while IFRS S2 addresses climate-related disclosures. These standards, effective as of 2024, are being adopted or referenced in multiple jurisdictions worldwide, highlighting a global trend towards harmonization of sustainability reporting practices [15].

The transition from voluntary CSR reporting to mandatory sustainability disclosure reflects a growing recognition that financial metrics alone are insufficient for assessing corporate performance [16]. Recent research highlights that robust ESG reporting enhances transparency and comparability across firms and sectors, serving as a strategic governance tool rather than merely a compliance measure. For example, a 2024 study examines how ESG regulation influences financial reporting quality, showing that better alignment with sustainability criteria enhances data reliability for investors and regulators [17].

Corporate sustainability reporting is not only an exercise in transparency but also a strategic tool that enables companies to assess and communicate their ESG performance. Internal analysts and evaluators play a central role in this process, acting as both producers and interpreters of financial and non-financial information [18]. The quality of sustainability reports largely depends on the integration of ESG metrics into internal management systems and the ability of professionals to assess these indicators critically.

Numerous studies have highlighted the connection between sustainability reporting and corporate competitiveness [19,20]. Organizations that actively integrate sustainability principles into their operations are more likely to gain long-term advantages and strengthen their stakeholder relationships [21]. In this context, financial analysts are increasingly required to interpret ESG disclosures, assess sustainability risks, and factor these elements into company valuations. Likewise, auditors are expected to assure sustainability information, raising questions about the adequacy of existing standards and the boundaries of professional accountability [22].

Empirically examining this linkage, Khanchel et al. (2023) found that ESG reporting, combined with green innovation, has a positive influence on firms’ financial performance, particularly in the social and governance dimensions [23]. Moreover, studies on Asian emerging markets corroborate the positive relationship between ESG performance and financial outcomes, highlighting that such reporting can drive market confidence and operational efficiency in diverse economic contexts [24].

Theoretical frameworks, such as dual materiality, require professionals to go beyond traditional financial analysis and integrate environmental and social dimensions. Recent audit-focused research asserts that external auditors play a critical role in bridging gaps between technical ESG guidance and corporate reporting practices [25]. Moreover, the concept of the double materiality audit emphasizes the use of established financial audit procedures to validate ESG disclosures effectively [26].

In emerging economies, mixed-method empirical research reveals that motives and challenges significantly influence ESG disclosure levels [27]. Despite growing regulatory pressure and stakeholder expectations, firms vary considerably in their disclosure quality, reflecting differences in governance, resource capabilities, and the maturity of sustainability practices [28]. This underscores the need for context-sensitive frameworks to guide ESG integration.

The existing body of literature underscores that sustainability reporting is no longer an auxiliary disclosure mechanism but a core driver of corporate governance and strategic decision-making. While prior research has predominantly examined the conceptual and regulatory dimensions of ESG reporting, there is an increasing need to explore its operational implications for key professional actors [29]. Financial analysts and auditors play a central role in this transformation, as they interpret ESG information to inform investment decision-making. In contrast, auditors assure its accuracy, completeness, and compliance with regulatory frameworks [30]. This dual role becomes even more complex in the context of environmental investment management, where both market pressures and legal requirements converge to demand higher technical competence, methodological innovation, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Technological advances, particularly in digital innovation, are emerging as key catalysts for enhancing ESG performance. A recent study reveals that the adoption of generative AI significantly mediates the impact of digital innovation on corporate ESG outcomes, indicating that technology adoption and reporting quality are increasingly interlinked [31]. This aligns with broader findings that automated, digital reporting systems improve accuracy and stakeholder trust.

For financial analysts and other economists in the category, the shift from traditional performance evaluation to sustainability-integrated analysis presents a fundamental methodological challenge. Analysts must integrate ESG metrics—often qualitative and sector-specific—into valuation models that were historically designed for financial data [32]. This requires rethinking cash flow forecasts, risk assessment frameworks, and capital allocation models to account for environmental performance and climate-related risks. Moreover, EU Taxonomy compliance introduces technical requirements for classifying eligible and aligned activities, necessitating expertise in both financial modelling and ecological science. Recent studies have demonstrated that ESG-related disclosures have a substantial impact on analysts’ earnings forecasts and stock recommendations [33,34]. Still, the lack of standardized sectoral metrics remains a significant barrier to comparability and investment efficiency [35,36].

Auditors face parallel yet distinct challenges, primarily in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of sustainability information. The principle of dual materiality obliges auditors to assess not only how sustainability risks affect financial performance, but also how corporate operations impact environmental and social systems [37]. This expansion of scope demands familiarity with ESG reporting standards (e.g., ESRS, GRI) and the capacity to verify non-financial KPIs with the same rigor as financial figures [38]. Regulatory developments, such as the amendments to Directive (EU) 2022/2464, which introduce explicit obligations for sustainability assurance, are pushing the profession toward integrated audit approaches [1]. Empirical evidence suggests that the credibility of ESG disclosures increases significantly when they are subject to external assurance; however, differences in audit methodologies across jurisdictions can undermine consistency and investor trust [39,40].

This study adopts a qualitative, document-based research design that integrates a structured literature review with a legal-institutional analysis of the European sustainability reporting framework. Following the guidelines proposed by Webster and Watson (2002) for structured literature reviews [41] and supplemented with PRISMA-based document selection criteria [42], the analysis draws on peer-reviewed articles, EU legislative acts, and official technical reports from EFRAG and ESMA [13,14].

In this research, the primary normative sources include Directive (EU) 2022/2464 and Regulation (EU) 2020/852, complemented by sector-specific guidelines from the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). Academic literature was retrieved from Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases, with inclusion criteria limited to publications from 2019 to 2025, peer-reviewed status, and direct relevance to sustainability reporting, ESG metrics, or environmental investment analysis. Technical and policy papers from EFRAG and ESMA were included to capture practical and regulatory perspectives.

The conceptual framework builds on the integration of institutional theory and stakeholder theory in the context of sustainability reporting. Institutional theory explains how regulatory pressures, such as the EU’s mandatory sustainability reporting requirements, shape organizational structures and disclosure practices [43]. Stakeholder theory complements this by emphasizing the role of investors, regulators, and civil society in demanding transparent and comparable ESG information [44]. This dual-theoretical approach enables an understanding of how compliance is not merely a legal obligation but also a strategic instrument for legitimacy, competitiveness, and access to sustainable finance. The model further incorporates the Resource-Based View (RBV) to account for the organizational capabilities required to implement reliable sustainability reporting systems [45].

3. Research Methodology

The methodological approach integrates a qualitative review of EU sustainability legislation and specialized literature with a quantitative survey conducted among professionals. The qualitative stage was used to define the conceptual framework and derive research hypotheses, while the quantitative stage enabled empirical testing through statistical models.

The conceptual framework, which incorporates institutional theory and stakeholder theory, informs sustainability reporting under the dual materiality principle. Their integration leads to three hypotheses on the evolving roles of financial analysts and auditors in environmental investment management.

H1.

Higher levels of ESG-related professional experience are significantly associated with increased use of ESG data in internal analysis.

H2.

Familiarity with EU sustainability legislation significantly predicts the ability to integrate ESG indicators into evaluation models.

H3.

Multiple factors, including professional qualification, ESG experience, legislative familiarity, training, ESG data usage, trust in standards, digitalization, indicator knowledge, and professional adaptation to ESG audit, significantly predict the ability to integrate ESG indicators into evaluation models.

To empirically explore professional readiness for ESG integration and the adaptation of auditing practices, considering the EU’s evolving sustainability regulatory framework, this study utilized a structured survey as its primary data collection method. The survey was designed based on the theoretical constructs discussed in the manuscript, with a particular focus on the roles of professional qualifications, legislative literacy, ESG experience, and digital competencies in shaping sustainability-related skills. This design facilitated the quantitative operationalization of abstract concepts, enabling hypothesis testing through correlation and regression analyses. Additionally, the survey was structured to capture both subjective self-assessments and objectively relevant competencies, making it effective for evaluating individual variations across diverse professional categories. Its clarity, theoretical foundation, and statistical applicability position it as a valid and reliable tool for assessing ESG preparedness in practice. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to synthesize the data. At the same time, correlational tests were conducted to identify relationships between key variables, such as the capacity to integrate ESG into evaluations and the adoption of information technologies.

Drawing on theoretical models of professional competence and regulatory compliance, the analysis uses a structured survey to evaluate perceptions and self-assessed capabilities across a representative sample of economists, analysts, and auditors. By applying statistical techniques including Pearson correlations, simple and multiple linear regressions, and Likert-scale-based ranking, the study seeks to identify the most influential predictors of ESG application. The methodological rigor ensures that each hypothesis is tested against quantifiable indicators, offering both empirical validation and actionable insights for ESG education, professional development, and institutional alignment.

This structured survey, validated by the institutional ethics committee, consisting of 10 professional questions, was distributed nationally to economists, analysts, and auditors identified through professional networks. The questionnaire employed a three-point Likert scale to capture respondents’ perceptions in a simple and accessible format. The response options were structured as 1 = low extent, 2 = moderate extent, and 3 = high extent, reflecting the degree to which each determinant was perceived as relevant to ESG preparedness. The three-point format was considered appropriate for ensuring clarity and consistency among professional respondents, while minimizing potential ambiguities associated with more complex scales.

The study employed a convenience sampling strategy, as respondents were selected from professional networks that provided accessible and relevant participants for the research objectives. This non-probabilistic method was deemed suitable for an exploratory study, as it enabled the collection of data from individuals with direct exposure to financial evaluation, auditing, and sustainability reporting practices. While convenience sampling does not ensure representativeness for the entire population of financial professionals, it offers practical advantages in exploratory contexts by capturing insights from respondents that are immediately relevant to the topic being investigated.

The study was conducted from October 2024 to January 2025, during which 150 responses were collected. After processing, 145 of these responses were deemed suitable for analysis using aggregated data in SPSS v30. The participants in the study were selected through convenience sampling, as they were readily available and aligned with the study’s objectives. Each participant was informed about the purpose of the study and provided their consent before completing the survey. Anonymity was maintained for all respondents throughout the data collection and analysis process, ensuring adherence to ethical research standards through institutional certification.

The reliability of the survey instrument was tested using Cronbach’s alpha. The coefficient obtained for the ten-item scale was 0.61, which indicates an acceptable level of internal consistency for exploratory research [46]. Although this value is slightly below the conventional threshold of 0.70, it is consistent with the multidimensional nature of the instrument, which was designed to capture several complementary aspects of professional preparedness. The inclusion of heterogeneous dimensions inevitably reduced the overall homogeneity of responses, but at the same time provided a more comprehensive perspective on ESG readiness. To assess potential common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted through principal component analysis. The results showed that the first factor accounted for 28.67% of the variance, which is well below the 50% threshold. This indicates that common method bias is unlikely to pose a serious threat to the validity of the findings.

Regression models were tested for multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerance values. The obtained VIFs ranged from 1.07 to 3.74, and tolerances from 0.27 to 0.93, all of which fall within conventional thresholds (VIF < 10, tolerance > 0.1). These results indicate that no severe multicollinearity is present in the models.

The robustness of the estimated relationships against potential omitted-variable bias was assessed using the coefficient stability framework of Oster [47]. This method compares reduced and extended regression models, examining how the inclusion of observed controls affects both the estimated coefficients and the explanatory power (R2). On this basis, parametric bounds were calculated to indicate the extent of unobserved selection required to alter the main effects. In line with the approach illustrated by Dantas et al. [48], the analysis was anchored in a fixed-effects logic, with group-level controls (profession, organizational type, and experience) serving as proxies for unobserved heterogeneity. This combined procedure provided a means of testing whether the direction and significance of the coefficients remain stable under plausible assumptions regarding selection on unobservables, thereby reinforcing the internal validity of the findings.

4. Results

These results demonstrate how individual factors, such as professional qualifications, ESG-related experience, familiarity with EU legislation, and digital competencies, contribute to the integration of ESG principles into financial analysis and auditing processes. The sample comprised a total of 145 respondents, representing professionals involved in ESG analysis, reporting, or auditing, categorized into three professional groups: economists (52%), analysts (31%), and auditors (17%). This distribution reflects a diverse professional base, yet one that is predominantly shaped by roles with strong ties to financial modelling and economic reporting. Economists formed the majority, which is consistent with the survey’s emphasis on ESG evaluation, legislative familiarity, and data integration. Analysts and auditors added depth to the sample by representing more technical and compliance-oriented perspectives, respectively.

This composition facilitated a nuanced understanding of how ESG-related competencies vary across professional functions. The inclusion of both operational (analysts), strategic (economists), and assurance (auditors) roles ensures that the regression models are grounded in the complex reality of sustainability reporting, where diverse professional backgrounds intersect.

The professional determinants of ESG preparedness were operationalized through ten survey items. These items capture distinct dimensions of professional and institutional readiness, ranging from qualifications and practical experience to familiarity with legislation, trust in reporting standards, use of ESG data, digitalization, and adaptation to ESG-related auditing. Table 1 presents the complete list of items that constitute the variables used in the subsequent statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of research items.

In Table 1, each item corresponds to a distinct yet interconnected dimension of professional competence in the context of ESG reporting and auditing. This item structure enabled the formulation of precise hypotheses and statistical modelling, ensuring alignment between theory, measurement, and empirical testing. The inclusion of both general and ESG-specific competencies underscores the multifaceted nature of professional readiness in the evolving regulatory environment.

Table 2 presents the analysis of the Likert-scale responses across the ten survey items, which reveals valuable insights into participants’ perceptions regarding professional adaptation to sustainability reporting and auditing. The highest-rated item was the capacity to integrate ESG into evaluation models (Item 3), with a mean score of 2.67 and an RII of 0.534, indicating a strong emphasis placed on the analytical ability to incorporate ESG criteria. Close behind, the familiarity with EU sustainability legislation (Item 4) and the use of ESG data in internal analysis (Item 6) also ranked highly, suggesting that both legal knowledge and practical data application are perceived as essential competencies in this evolving professional field. At the lower end of the ranking, Item 1 (Professional qualification level) received the lowest RII, suggesting that respondents may consider formal qualifications less decisive than applied skills and regulatory awareness. The overall distribution reflects a greater appreciation for operational capabilities and ESG-specific knowledge over general credentials.

Table 2.

Data aggregation results.

The Pearson correlation matrix revealed several significant associations among the core constructs measured in the survey (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation results.

The correlation results confirm the theoretical coherence and internal consistency of the item structure. It is found that Items 3 and Items 4 present an almost perfect positive correlation of r = 0.977. Thus, it is considered that respondents who are more familiar with CSRD and the EU taxonomy are much more prepared to integrate ESG considerations into financial assessments. This strong relationship provides direct empirical support for H2. All of Item 3 is included in the multiple regression model to highlight additional possible links, as per H3. On the other hand, it is observed that the support defined for H1 consists of moderate associations, such as those between Items 2 and Item 6 (r = 0.430). The results reveal an interconnection between experience and ESG application, partially validating H1. Therefore, data modelling to substantiate H1 does not proceed further.

For hypotheses H2 and H3, the preparation of the regression models included additional tests to ensure the relationship of the items. The results of these tests are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Anova Test results.

The ANOVA test for H2 utilized a single predictor, and multicollinearity was not an issue, as evidenced by a VIF of 1. This finding confirms that the predictor variable operates independently and does not overlap with other variables in this context. The results from both the ANOVA and collinearity diagnostics reinforce the model’s robustness and simplicity, providing strong empirical support for H2.

The model for H3 yielded a highly significant F-statistic (p < 0.001), confirming that the overall regression model is robust and the set of predictors significantly improves the explanation of variance in the dependent variable. To evaluate collinearity, VIF was computed for each independent variable. Results indicated no critical multicollinearity, with all VIF values remaining well below the conventional threshold. The resulting synthetic models are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Model’s summary for regression.

The strength of the model for H2 was further underscored by an R2 value of 0.954, indicating that 95.4% of the variation in ESG integration can be attributed to differences in respondents’ knowledge of EU sustainability legislation. The model’s coefficient of determination (R2) for H3 was exceptionally high at 0.955, indicating that 95.5% of the variance in ESG integration ability is explained collectively by the predictors: professional qualification (Item 1), ESG experience (Item 2), legal familiarity (Item 4), training (Item 5), ESG data usage (Item 6), digitalization (Item 8), indicator knowledge (Item 9), and ESG audit adaptation (Item 10).

The regression model developed to test H2 thus assessed whether professionals’ familiarity with EU sustainability legislation (Item 4) significantly predicts their ability to integrate ESG indicators into financial valuation models (Item 3), and the result is:

Item 3 = 0.076 + 0.974 × Item 4

The analysis yielded a powerful linear relationship, with a regression coefficient (β1) of 0.974, indicating that for each unit increase in legislative familiarity, the ability to apply ESG indicators increases by nearly one unit. The intercept (β0) was very small, further confirming the tight alignment between the two variables. Most notably, the model produced an R2 value of 0.954, meaning that 95.4% of the variance in ESG integration ability is explained solely by knowledge of legislation. The model is both statistically robust and theoretically coherent, suggesting a high level of predictive validity, validating H2.

The multiple linear regression model for H3 tested whether eight distinct professional attributes jointly predict the ability to integrate ESG indicators into financial evaluation processes. The resulting multiple regression is:

where Item 4 demonstrated the most substantial individual effect, with a coefficient of β = 0.939, confirming its dominant role in enabling ESG integration. Other variables contributed less significantly, with some displaying minimal or negative coefficients when the rest of the model was controlled for. However, this suggests that ESG integration is influenced in a small manner by a diverse set of professional attributes, which validates H3.

Item 3 = 0.025 − 0.017 × Item 1 + 0.025 × Item 2 + 0.939 × Item 4 − 0.001 × Item 5 + 0.009 × Item 6 + 0.033 × Item 7 − 0.012 × Item 8 + 0.019 × Item 9 + 0.006 × Item 10,

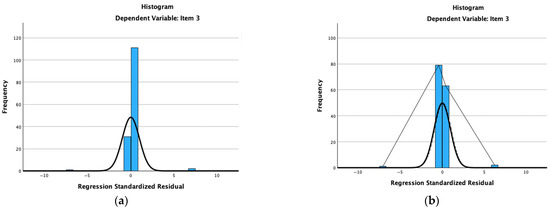

As part of the regression diagnostics, standard residual plots were analysed to assess the validity of key assumptions underlying the multiple linear regression model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Regression standardized results: (a) linear regression of H2; (b) multiple regression of H3.

The regression models illustrated in Figure 1 confirm that familiarity with EU legislation is the strongest determinant of ESG integration ability, while other predictors showed limited or no statistical significance. These results are consistent with methodological checks, including acceptable reliability of the instrument (Cronbach’s α = 0.61), absence of severe multicollinearity (VIF values between 1.07 and 3.74), and no evidence of critical common method bias (Harman’s test: 28.67%).

To assess robustness to omitted-variable bias, coefficient stability was evaluated using the parametric bounds framework [47,48]. A comparison was made between a reduced model, (Item 3 on Item 4; , ) and an extended model that encompasses the complete set of controls (Items 1–2 and 5–10; , ).

β* = β1 − δ × (β1 − β0) × (Rmax − R12)/(R12 − R02)

Setting and , the adjusted bound is , indicating that the sign and economic interpretation of the main effect are preserved under plausible selection on unobservables. The implied required to drive the coefficient to zero would be negative (≈−1.22), reinforcing the conclusion that the relationship between legislative familiarity and ESG integration ability remains directionally robust to omitted correlated factors.

The convergence of graphical results and diagnostic validation supports the robustness of the interpretations, while also underlining that regulatory familiarity outweighs other professional determinants in shaping ESG preparedness. The results indicated that the residuals closely followed the diagonal line, suggesting that the errors are approximately normally distributed.

5. Discussion

Theoretical findings from the literature and regulatory review suggest that integrating ESG principles into financial and audit processes is no longer a voluntary or peripheral task, but a core strategic and legal obligation under the evolving European framework. CSRD and the EU Taxonomy mandate a shift from narrative sustainability statements to quantifiable, verifiable ESG disclosures, effectively redefining the roles of financial analysts, accountants, and auditors. These regulations introduce structured, indicator-based reporting aligned with the principles of double materiality, requiring professionals to interpret financial data not only, but also to assess environmental and social risks and impacts. This reconceptualization positions ESG competence as a regulated form of expertise, not merely a professional preference. As a result, the institutional context demands a new level of alignment between regulatory compliance, technical capacity, and professional development, placing ESG integration at the intersection of legal mandates and practical execution.

This study confirms that familiarity with these legislative frameworks is not only conceptually central but statistically the strongest predictor of ESG integration capabilities. Additionally, the empirical evidence supports the experiential dimension of ESG proficiency: professionals with greater ESG-related experience were significantly more likely to apply ESG data in internal analysis. This validates the view that ESG literacy is both learned and used, and that technical compliance alone is insufficient. The importance of digital tools also emerged as a complementary factor, with strong correlations and regression values, illustrating the interdependence between data capabilities and ESG implementation.

The reliability analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.61, which is acceptable for exploratory research designs, reflecting the multidimensional structure of the instrument that captures several distinct aspects of professional preparedness rather than a single homogeneous construct. While this reduces internal consistency, it provides a broader view of ESG readiness. Nevertheless, the moderate coefficient highlights a methodological limitation of the study, suggesting that future research could benefit from more refined instruments or from confirmatory approaches that ensure higher reliability across different professional categories.

In addition to a cross-sectional design, the study faces limitations related to measurement validity. Some constructs, while theoretically grounded, revealed very high correlations, suggesting possible conceptual redundancy. Although exploratory validity checks (such as Harman’s single-factor test) did not indicate severe common method bias, the discriminant validity of the constructs remains limited. Future studies should refine measurement instruments and apply confirmatory approaches to strengthen construct validity and minimize overlaps between professional determinants.

The strength of this regression model of H2 has several critical implications for future professional development and institutional capacity-building in ESG finance and reporting. First, the overwhelming predictive power of legislative familiarity on ESG integration suggests a solid understanding of frameworks. As such, ESG literacy must become a core component of educational programs for analysts, auditors, and finance professionals. Furthermore, the findings indicate that even highly skilled practitioners may struggle to apply ESG metrics effectively if they lack detailed knowledge of current regulatory requirements. To address this, organizations should implement targeted training programs that focus on regulatory updates, the interpretation of legislative texts, and compliance-driven ESG evaluation. At a policy level, these results support the integration of EU ESG regulations into national professional qualification standards and ongoing certification processes. Ultimately, bridging the gap between legislation and practice will be fundamental to achieving both regulatory compliance and meaningful ESG impact.

The results of this multiple regression of H3 have important implications for both ESG training and human capital development. The overwhelming predictive strength of EU legislative knowledge suggests that regulatory literacy must be prioritized in both academic and professional training curricula. Moreover, the inclusion of additional factors underscores the interdisciplinary skill set required for ESG evaluation. Employers and regulators should view ESG competence as more than a single skill; it involves a composite of legal understanding, technical expertise, and practical engagement. Institutions designing certification programs or recruitment criteria should therefore assess professionals across multiple dimensions rather than focusing solely on experience or academic background. This regression also highlights the need for integrated training programs that simultaneously address ESG law, practical data utilization, and evolving audit practices to develop professionals capable of meeting modern sustainability standards.

The regression results yielded very large effect sizes, with EU legislation familiarity emerging as the dominant determinant of ESG integration ability. While such findings highlight the centrality of institutional drivers, they may also reflect partial conceptual overlap between constructs. To assess potential common method bias, a Harman’s single-factor test was performed, and the first factor explained 28.67% of the variance, well below the critical threshold of 50%. This suggests that measurement artifacts do not entirely explain the extreme effect sizes, although future research would benefit from refined constructs and confirmatory validity testing.

The analysis suggests that a combination of professional and technical factors significantly influences the integration of sustainability indicators into financial evaluation. Among these, familiarity with European legislation emerges as the most influential determinant, providing financial professionals with the normative clarity required to operationalize ESG criteria. ESG-related professional experience also contributes positively, facilitating the practical application of non-financial data in evaluation and auditing processes. Additionally, digital competencies facilitate this integration by enabling the use of standardized tools and automated reporting systems, thereby enhancing both efficiency and comparability. Taken together, these findings suggest that professional qualifications alone are insufficient predictors of ESG readiness; instead, effective integration requires a balanced interplay between regulatory literacy, accumulated experience, and digital proficiency.

Although this study focuses on the professional determinants of ESG preparedness, there are situations where the influences on the reporting environment are determined by ESG investors or managers involved in this process. The unprecedented expansion of assets managed by ESG-oriented funds has the potential to shape the incentive structures of analysts and auditors, extending their motivations beyond traditional pecuniary considerations. This external pressure may indirectly influence professional preparedness by creating expectations for greater transparency, comparability, and assurance of sustainability information. Although this dimension was not directly tested in the present analysis, it constitutes a critical contextual factor and a promising direction for future research. Furthermore, in line with Oster’s framework [47] on unobservable selection and coefficient stability, future research could extend the analysis by examining whether professional determinants remain robust when accounting for the confounding effects of ESG investment flows. This direction is consistent with the approach illustrated by other authors [48], who applied the parametric bounds method in a fixed-effects context. Such an expansion would enhance the reliability of the findings and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how regulatory, professional, and investor-driven forces interact in shaping ESG reporting practices.

6. Conclusions

This study confirms that the successful integration of ESG principles into financial evaluation and auditing practices is highly dependent on a combination of regulatory knowledge, professional experience, and practical competencies, including familiarity with digitalization and relevant indicators. The strongest statistical association was observed between familiarity with EU legislation and the ability to integrate ESG information. Moreover, ESG-related experience and digital skills were shown to complement this effect, reinforcing the idea that ESG readiness is not a single competency but a multidimensional construct. The quantitative approach, using Likert analysis, Pearson correlations, and both simple and multiple regression models, provided robust empirical validation for the three hypotheses, aligning well with theoretical assumptions derived from recent EU sustainability policies.

Despite the robustness of the statistical findings, this study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the data are based on self-reported perceptions, which may introduce subjectivity or social desirability bias, especially in areas such as legal knowledge or practical ESG application. Second, the sample is primarily drawn from economist, analyst, and auditor roles, which may limit the generalizability of results to other professional domains. Additionally, although the regression models indicate strong predictive relationships, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not permit conclusions about causality. Finally, this study did not consider cultural or organizational factors that may influence ESG behaviour.

Future studies could expand upon these findings by incorporating longitudinal designs that track the development of ESG competencies over time and their translation into concrete reporting outcomes. Further exploration of organizational culture, leadership support, and internal ESG could help explain variation beyond individual-level predictors. Comparative analyses between sectors or EU vs. non-EU professionals may also reveal how context influences ESG readiness. Additionally, integrating qualitative methods could enrich the understanding of how professionals interpret and apply ESG frameworks in practice. Ultimately, future research could investigate the impact of formal ESG certification programs on enhancing professional adaptation and competence across various industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-I.T., A.-N.C. and L.-C.T.; methodology, V.R., A.-N.C. and F.R.; software, A.-I.T. and V.R.; validation, A.-I.T., V.R. and L.-C.T.; formal analysis, A.-N.C., A.-I.T. and F.R.; investigation, A.-I.T., V.R. and F.R.; resources, V.R., L.-C.T. and F.R.; data curation, A.-N.C., L.-C.T. and F.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-I.T., A.-N.C. and F.R.; writing—review and editing, V.R. and L.-C.T.; visualization, A.-I.T. and V.R.; supervision, V.R. and L.-C.T.; project administration, V.R. and L.-C.T.; funding acquisition, A.-N.C. and F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the DIGIT project, grant number 486-721/2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approved by the Ethics Committee of Valahia University of Targoviste (No. 1067) on 1 July 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make the raw data supporting this article’s conclusions available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| CSRD | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

| DNSH | Do No Significant Harm |

| EFRAG | European Financial Reporting Advisory Group |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| ESMA | European Securities and Markets Authority |

| ESRS | European Sustainability Reporting Standards |

| EU | European Union |

| GAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| IFRS | International Financial Reporting Standards |

| ISSB | International Sustainability Standards Board |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| KPMG | Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler (Audit Firm) |

| MIS | Management Information Systems |

| OJ | Official Journal of the European Union |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

| RII | Relative Importance Index |

| SGX | Singapore Exchange |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SSRN | Social Science Research Network |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| XBRL | eXtensible Business Reporting Language |

References

- European Parliament. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 … as Regarding Corporate Sustainability Reporting. OJ L 322, 16 December 2022; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2022; pp. 15–80. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2464/oj/eng (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment. OJ L 198, 22 June 2020; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2020; pp. 13–43. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32020R0852 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Abeysekera, I. A framework for sustainability reporting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2022, 13, 1386–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Jobst, D. An overview of corporate sustainability reporting legislation in the European Union. Account. Eur. 2024, 21, 320–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 Establishing the Recovery and Resilience Facility; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32021R0241 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Choi, S.U.; Lee, W.J. Financial Statement Comparability and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, E.M.; Ionescu-Feleagă, L.; Ferrat, Y. The evolution of environmental reporting in Europe: The role of financial and non-financial regulation. Int. J. Account. 2022, 57, 2250008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novicka, J.; Volkova, T.; Savina, N. Regulation of Sustainability Reporting Requirements—Digitalisation Path. Sustainability 2024, 17, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakuwanika, M.; Panicker, M. The Role of Environmental Accounting in Mitigating Climate Change: ESG Disclosures and Effective Reporting—A Systematic Literature Review. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.C.; Hsu, C.W.; Lin, C.Y. Exploring Key Factors Influencing ESG Commitment: Evidence from Taiwanese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thottoli, M.M.; Islam, M.A.; Sobhani, F.A.; Rahman, S.; Hassan, M.S. Auditing and Sustainability Accounting: A Global Examination Using the Scopus Database. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG). Available online: https://www.efrag.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). Available online: https://www.esma.europa.eu/ (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- ISSB Issues Inaugural Global Sustainability Disclosure Standards. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/news/2023/06/issb-issues-ifrs-s1-ifrs-s2/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Krasodomska, J.; Zarzycka, E.; Zieniuk, P. Voluntary sustainability reporting assurance in the European Union before the advent of the corporate sustainability reporting directive: The country and firm-level impact of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1652–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafni, D.; Palas, R.; Baum, I.; Solomon, D. ESG regulation and financial reporting quality: Friends or foes? Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 105017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, T.M.; Odagiu, A.; Pop, H.; Paulette, L. Sustainability performance reporting. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duric, Z.; Potočnik-Topler, J. The role of performance and environmental sustainability indicators in hotel competitiveness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, P. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Trujillo, A.M.; Gonzalez-Perez, M.A.; Baena-Rojas, J.J. Sustainable strategy as a lever for corporate legitimacy and long-term competitive advantage: An examination of an emerging market multinational. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2024, 36, 112–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, P.; Barac, K. Rational purpose requirement and sustainability reporting assurance. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2025, 16, 156–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanchel, I.; Lassoued, N.; Baccar, I. Sustainability and firm performance: The role of environmental, social and governance disclosure and green innovation. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 2720–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Tang, J.; Walton, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. Auditor sustainability focus and client sustainability reporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2024, 113, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applebaum, D.; Duan, H.K.; Hu, H.; Sun, T. The double materiality audit: Assurance of ESG disclosure. SSRN Electron. J. 2023. Available online: https://sacredheart.elsevierpure.com/ws/portalfiles/portal/39957910/SSRN-id4367032.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Adardour, Z.; Ed-Dafali, S.; Mohiuddin, M.; El Mortagi, O.; Sbai, H.; Bouzahir, B. Exploring the drivers of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure in an emerging market context using a mixed methods approach. Future Bus. J. 2025, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbithi, E.; Moloi, T.; Wangombe, D. An empirical examination of board-related and firm-specific drivers on risk disclosure by listed firms in Kenya: A mixed-methods approach. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2023, 23, 298–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, A.O.; Osei, A.; Kongkuah, M. Exploring the ESG-circular economy nexus in emerging markets: A systems perspective on governance, innovation, and sustainable business models. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 5901–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.S.; Senadheera, S.S.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Withana, P.A.; Chib, R.; Rhee, J.H.; Ok, Y.S. Navigating the challenges of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting: The path to broader sustainable development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellhorn, T.; Wagner, V. The forces that shape mandatory ESG reporting. In Research Handbook on Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance; Kuntz, T., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J. Empirical Analysis of Digital Innovations Impact on Corporate ESG Performance: The Mediating Role of GAI Technology. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.01041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancel, F.; Glavas, D.; Karolyi, G.A. Do ESG factors influence firm valuations? Evidence from the field. Financ. Rev. 2025, 60, 1191–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Candio, P. The independent and moderating role of choice of non-financial reporting format on forecast accuracy and ESG disclosure. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; Castillo-Díaz, F.J.; Batlles-delaFuente, A.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J. Enhancing competitiveness and sustainability in Spanish agriculture: The role of technological innovation and corporate social responsibility. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e70021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshubiri, F. Investment obstacles to sustainable development and competitiveness index. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory ESG and Sustainability Reporting: Economic Analysis and Literature Review. Rev Acc. Stud. 2021, 26, 1176–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, A.; Elshandidy, T. Does sustainability disclosure improve analysts’ forecast accuracy? Evidence from European banks. Financ. Innov. 2025, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. Challenges and Opportunities in ESG Reporting and Assurance. 2022. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/our-insights/esg/challenges-and-opportunities-in-esg-reporting-and-assurance.html (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Tseng, T.Y.; Shih, N.S. The effects of CSR report mandatory policy on analyst forecasts: Evidence from Taiwan. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Brotherton, M.C.; Talbot, D. What you see is what you get? Building confidence in ESG disclosures for sustainable finance through external assurance. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2024, 33, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Q. 2002, 26, xiii–xxiii. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4132319 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Ed-Dafali, S.; Adardour, Z.; Derj, A.; Bami, A.; Hussainey, K. A PRISMA-Based Systematic Review on Economic, Social, and Governance Practices: Insights and Research Agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1896–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Oster, E. Unobservable Selection and Coefficient Stability: Theory and Evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2019, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, M.M.; Merkley, K.J.; Silva, F.B. Government Guarantees and Banks’ Income Smoothing. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2023, 63, 123–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).