1. Introduction

Korea’s unique corporate ecosystem, characterized by the dominance of large family-owned conglomerates (chaebols) and an active policy push for SME development, provides a compelling backdrop to examine how mergers and acquisitions (M&A) can foster sustainable growth for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). M&A plays a pivotal role globally in enabling companies to adapt and remain competitive in dynamic markets [

1]. However, whether any given acquisition ultimately contributes to a firm’s sustainable long-term growth or merely offers a short-term boost depends on how well the deal is strategized and executed [

2]. In this study, we analyze how key deal characteristics—specifically the target firm’s listing status (public vs. private), the acquiring firm’s size, and the strategic scope of the deal (focus vs. diversification)—shape short-term shareholder wealth outcomes for Korean SME acquirers. By focusing on M&A transactions involving Korean SMEs, we explore these issues in an emerging market context [

3], linking immediate market reactions to the longer-term goal of building a resilient, sustainable business model.

As an emerging economy with distinctive institutional features, South Korea offers an important context for these strategic M&A questions. The Korean business landscape is dominated by chaebols that heavily influence industry dynamics and capital flows, often leaving independent SMEs at a disadvantage in terms of access to capital, talent, and technology [

4]. Korean SMEs also tend to have concentrated ownership and founder-led management, resulting in governance dynamics that differ from those of widely held firms in Western economies [

5]. Meanwhile, Korea’s institutional environment—including government policies and regulations aimed at fostering SME innovation and growth—shapes how smaller firms pursue expansion opportunities such as M&A [

6]. These contextual factors can significantly influence M&A outcomes. By examining Korean SME acquirers, we can assess whether established patterns of M&A success hold true in a chaebol-dominated, policy-influenced setting.

Prior research in developed markets provides a baseline for comparison. In the United States and Europe, acquirers typically realize on average zero or slightly negative abnormal returns at M&A announcements (especially when acquiring public companies), whereas acquisitions of private firms or subsidiaries often yield modest positive gains for bidders [

7]. Similarly, numerous studies find that smaller acquiring firms tend to outperform larger ones in announcement-period returns, reflecting the greater strategic agility and disciplined decision-making of SMEs. These patterns suggest that target listing status and acquirer size are key determinants of short-term M&A success. However, it remains uncertain whether the same “listing effect” and “size effect” observed in mature markets apply in the Korean context, where institutional differences—such as the prevalence of business groups and different governance norms—could lead to different outcomes [

8]. In addition, empirical findings on diversification strategy are mixed [

9]: diversifying into new industries can spread risk and open new growth opportunities, but can also strain managerial resources and dilute a firm’s core focus, especially for smaller acquirers. Our study addresses these gaps by investigating 155 M&A events undertaken by KOSDAQ-listed Korean SMEs from 2016 to 2020. Using an event study approach and regression analysis, we identify how the target’s listing status, the acquirer’s size, and the deal’s diversification or focus influence shareholder value in this specific environment. We include two indicator variables for target listing status—Public_Dummy and Private_Dummy—with Subsidiary targets serving as the omitted reference category to avoid the dummy variable trap.

Through this analysis, we aim to contribute new evidence and insights into sustainable business growth via M&A in an underexplored setting. Our study operationalizes sustainable business models (SBMs) through a two-pronged empirical design. Specifically, short-term investor expectations, captured by announcement-period cumulative abnormal returns (CAR

1), and long-term performance realization, captured by post-merger return on operating cash flow (ROCF), serve as proxies for sustainable value creation. The Korean SME context allows us to test established M&A theories under different institutional conditions, thereby extending the literature on M&A outcomes and strategic sustainability. We ground our investigation in resource-based, agency, and signaling theory perspectives, while framing our interpretation of the results around the long-term resilience of the firm rather than just short-term financial gains. In doing so, our study highlights the conditions under which Korean SME acquirers create value for shareholders and how those strategic decisions align with the firms’ capacity to adapt and thrive in the long run. These findings also offer practical implications for both SME executives and policymakers by identifying value-enhancing acquisition strategies for smaller firms and suggesting how supportive policies can help facilitate sustainable growth through prudent M&A.

2. Literature Review

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) have long been examined for their effects on shareholder value. Classic event studies show that targets earn substantial positive abnormal returns at announcements, whereas acquirers often realize small or negative short-term returns. Subsequent research, however, identifies conditions under which bidders do gain value, highlighting deal characteristics and firm fundamentals. More recently, scholars have framed M&A as a lever for sustainable business model (SBM) innovation, noting that post-deal reconfiguration can enhance resilience and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) outcomes [

10]. Large-sample evidence indicates that acquisitions can be followed by improvements in acquirers’ ESG performance, suggesting that strategic deals are not only financial events but also mechanisms for adapting business models to evolving stakeholder expectations.

Multiple theoretical lenses help explain these patterns. The resource-based view (RBV) sees acquisitions as a means to internalize valuable, rare, inimitable, and organizationally embedded resources that underpin sustained advantage. Agency theory cautions that deals may reflect managerial self-interest (e.g., empire-building), particularly in firms with slack, which can erode value. Signaling and information economics emphasize how deal design conveys information to markets (e.g., equity financing can signal overvaluation). Integrating these perspectives clarifies how target listing status, acquirer size, and deal scope shape both near-term market reactions and the longer-run trajectory of the combined firm.

2.1. Target Listing Status (Public vs. Private Targets)

Briefly, RBV implies that value creation depends on the acquirer’s ability to absorb and deploy the target’s resources; agency theory draws attention to governance features—such as ownership concentration and founder leadership, common in Korean SMEs—that may curb empire-building but introduce other frictions. To ground these expectations, we also draw on classic management scholarship [

3,

4,

5], together with finance theory (RBV, agency, signaling). In combination, these perspectives suggest that how information is produced, processed, and acted upon in an acquisition will shape both investors’ immediate assessments and longer-run value creation.

A substantial empirical literature documents a listing effect: acquisitions of private firms (including subsidiaries) tend to generate higher announcement-period abnormal returns for acquirers than acquisitions of public firms. In U.S. data, bidders earn positive abnormal returns when purchasing private companies, whereas buying public targets typically yields zero or negative returns [

7]; similar evidence favoring unlisted targets has been reported [

11]. The common interpretation is that markets expect relatively greater value capture in private-target deals.

Two mechanisms are most often cited. (1) Information asymmetry and competition. Private firms disclose less and lack a continuously updated market price, allowing capable acquirers to identify undervalued assets and negotiate on favorable terms. Public targets, by contrast, face broader scrutiny and more bidders, which elevates premiums and compresses acquirer gains; it has been documented that premiums are materially higher for public than comparable private targets [

12]. (2) Signaling via payment method. Stock-financed purchases of private targets are often viewed positively because target owners’ willingness to accept acquirer stock signals confidence in the combined firm’s prospects [

13]. In contrast—and consistent with prior arguments on adverse selection [

14]—issuing equity to acquire a public firm can provoke a negative reaction. Thus, the same payment instrument (stock) can convey opposite signals depending on the target’s listing status.

From an RBV–sustainability perspective, private-target acquisitions can also advance SBMs by internalizing proprietary know-how and niche capabilities that, once integrated, enhance resilience and long-term competitiveness. Public-target deals, by contrast, often entail higher purchase costs and—absent exceptional synergies—can strain financial and managerial bandwidth, jeopardizing sustainable growth if integration underperforms.

While the listing effect is well established in Western markets, its magnitude in emerging economies depends on institutional conditions (e.g., disclosure regimes, enforcement, business-group prevalence). Recent evidence suggests that the effect often persists in Asia, though country-specific features can alter outcomes [

15,

16,

17]. Against this backdrop, focusing on Korean SMEs provides a stringent test of how listing status operates in an emerging-market setting with distinctive governance and market structures.

2.2. Acquirer Size

The size of the acquiring firm is another critical factor influencing M&A outcomes. Numerous studies document a pronounced “size effect” in acquisitions: smaller acquirers tend to outperform larger acquirers in terms of announcement returns. In an influential study of over 12,000 deals, it was found that small and mid-sized acquiring firms earned significantly higher abnormal returns around M&A announcements than large acquirers [

18]. Conversely, very large bidders often realize zero or negative shareholder returns on average. This inverse relationship between acquirer size and performance has been confirmed in various markets. For example, studies on Korean M&A have reported that smaller acquiring firms earn significantly higher CARs than larger firms, reflecting similar dynamics in an emerging market context [

19,

20,

21].

Several theoretical arguments explain why smaller acquirers often fare better. According to agency theory, large corporations are more prone to agency problems and managerial overreach. With abundant internal cash flows, CEOs of large firms may indulge in value-destroying “empire-building” acquisitions that serve managerial interests (expanding the company or diversifying personal risk) rather than shareholders’ interests. The free cash flow theory argues that managers of cash-rich big companies are tempted to over-invest in acquisitions instead of returning excess cash to shareholders [

22]; such deals often lack a compelling strategic rationale or involve overpayment, leading to poor outcomes. Similarly, the hubris hypothesis [

23] posits that overconfident CEOs in large firms may overestimate their ability to generate synergies and end up paying too much for targets.

In contrast, SMEs and smaller acquirers tend to be more disciplined and strategic in their M&A decisions. Operating with tighter resources and often with owners or founder-managers deeply involved, smaller firms “cannot afford a costly M&A mistake.” Their deals are typically modest in size and carefully vetted for clear value-creation potential. Smaller acquirers also tend to focus on acquisitions that strengthen their core business, rather than chasing diversification for its own sake. Post-merger integration can be easier for smaller firms, as the acquired business represents a relatively larger piece of a simpler organization, allowing synergies to be realized more readily. This combination of prudent deal selection, agile integration, and strategic focus gives smaller acquirers an edge in delivering positive returns.

Empirical evidence strongly supports this narrative. In both the U.S. and Europe, large acquirers have often seen negligible or negative announcement returns, whereas small acquirers show positive returns on average. Notably, shareholders of very large U.S. companies collectively lost hundreds of billions of dollars on deals during a late-1990s merger wave, whereas small-firm acquirers in that period gained value [

24]. Emerging-market data echo the same theme: research on Korean mergers in the KOSDAQ market confirms that the size effect holds, with listed SMEs creating value through M&A while larger firms sometimes destroy it [

25]. From a sustainable business model perspective, this size effect implies that growth-through-acquisition can be an especially effective strategy for nimble smaller firms. Successful acquisitions by SMEs can meaningfully enhance their competitiveness and resilience by injecting new capabilities or market access. Smaller firms also integrate acquisitions without the bureaucratic inertia that plagues very large organizations.

In contrast, for large conglomerates, each acquisition may add complexity and dilute accountability, potentially stalling innovation and eroding long-term performance. The Korean experience provides cautionary examples: in some cases, large chaebol groups undertook M&A not for genuine synergies but to divert resources or prop up struggling affiliates (a form of tunneling), resulting in value destruction. Such cases underscore that when managers of big firms pursue deals for unsound reasons, M&A can undermine sustainable value creation. It is worth noting that larger acquiring firms, despite their weaker average stock market reactions, often have more resources and external pressure to improve sustainability practices after acquisitions [

10]. Recent studies find that acquirers with greater size and capacity tend to achieve higher ESG performance improvements post-merger. This suggests a trade-off: smaller acquirers excel in immediate shareholder gains, while larger acquirers might leverage M&A to advance longer-term ESG and stakeholder objectives. Ultimately, firm size and governance context critically determine whether an acquisition bolsters or hinders a firm’s long-term health.

2.3. Diversification Strategy: Related vs. Unrelated M&A

The third major factor is the strategic relatedness of an acquisition—whether the acquirer expands within its core industry or diversifies into a new one. The performance impact of diversification has been debated for decades. On the benefits side, classic finance highlights a potential “coinsurance” effect in conglomerate mergers, where combining businesses in unrelated industries can stabilize cash flows and reduce overall risk exposure. Diversification can also create economies of scope, as firms share resources, technologies, or distribution channels across divisions. In addition, internal capital markets can allocate funds more flexibly to high-potential projects that external investors might misprice or overlook. When pursued with clear strategic logic, such diversification can increase resilience and open new growth avenues—outcomes aligned with long-term sustainability goals.

On the costs side, extensive research documents a persistent diversification discount, with conglomerates often trading below the sum of their parts. An agency–theory perspective suggests that some diversifying deals reflect managerial self-interest (empire-building or employment-risk hedging) rather than value maximization. Operationally, moving far from the core can dilute focus and strain managerial bandwidth; integrating disparate businesses raises coordination costs and execution risk. Empirically, the market frequently reacts skeptically to unrelated expansions: Prior studies report systematically lower announcement returns for unrelated acquisitions than for within-industry deals [

26,

27], and it has also been shown that unrelated acquisitions are more likely to be divested later [

28]. Importantly, unrelated diversification undertaken under managerial overconfidence can depress post-merger performance by diluting managerial attention, raising integration complexity, and misallocating capital; any diversification benefits should thus be expected mainly when relatedness and integration capacity are high. In other words, diversification is not inherently value-creating or value-destroying; outcomes depend on why and how it is pursued, and on the firm’s ability to integrate.

From a sustainable business model perspective, a targeted, related expansion can be powerful: adjacency (e.g., shared technology, customers, or channels) increases the odds that capabilities transfer and synergies materialize. By contrast, broad, unrelated diversification risks overextension and can undermine sustainable growth if it pulls the firm away from core competencies. Notably, in emerging markets such as Korea, diversification also has an institutional dimension. Large business groups (chaebols) historically diversified widely to fill institutional voids (e.g., underdeveloped capital markets). Independent SMEs may feel pressure to diversify to compete or scale, yet they typically lack deep internal capital markets and political connections, making unrelated diversification particularly risky. In the environmental domain, some firms pursue “green” M&As—acquiring clean-tech or environmentally friendly businesses—to accelerate strategic transformation; such moves can improve environmental performance and economics when they fit the acquirer’s capabilities, though greenwashing motives may fail to deliver genuine innovation or financial gains [

29]. Overall, the literature advises a balanced approach: diversify only when the new business clearly complements the firm’s capabilities, and ensure the integration plan matches the deal’s complexity.

2.4. Summary of Literature and Research Gaps

In sum, three factors—target listing status, acquirer size, and deal relatedness—systematically shape M&A outcomes. Acquisitions of private firms and acquisitions by smaller, more agile bidders are generally associated with more favorable short-term returns, while related (focused) acquisitions tend to outperform unrelated (diversifying) ones on average. These regularities underscore that M&A is not homogeneous: deal context and strategic fit critically determine value creation.

Nevertheless, important gaps remain. First, a contextual gap: most evidence comes from large firms in developed Western markets; far less is known about SMEs in emerging economies. Market structures and governance conditions in Korea differ markedly from the U.S. and Europe, and SMEs behave differently from large multinationals. It is not assured that the Western “listing effect” or “size effect” carries over unchanged. Early studies in Asia (e.g., Japan, China) suggest similar patterns, but results vary with institutional context. By examining Korean SMEs, we address this under-represented setting and test whether known M&A factors apply in a chaebol-influenced, policy-active environment.

Second, a sustainability-integration gap: traditional M&A research emphasizes financial performance (short-term stock reactions or accounting metrics), whereas sustainability scholarship focuses on long-term resilience, stakeholder value, and adaptive capacity. Few studies explicitly connect these domains [

10]. We bridge this by interpreting M&A outcomes through the lens of sustainable business model development, pairing short-term market expectations (CAR) with realized operating outcomes (ROCF, 1–2 years) and situating results within an integrated theoretical frame.

Third, a theoretical–integration gap: many studies rely on a single lens (RBV, agency, or signaling). We integrate these perspectives to provide a more complete account of when and why M&As succeed. The next sections develop the research framework, state hypotheses on listing status, acquirer size, and diversification, and detail the empirical strategy. Our goal is to contribute empirically, by providing data-driven evidence from a new context, and theoretically, by showing how combining RBV, agency, and signaling explains conditions under which M&As maximize short-term shareholder wealth while laying foundations for sustainable business model innovation.

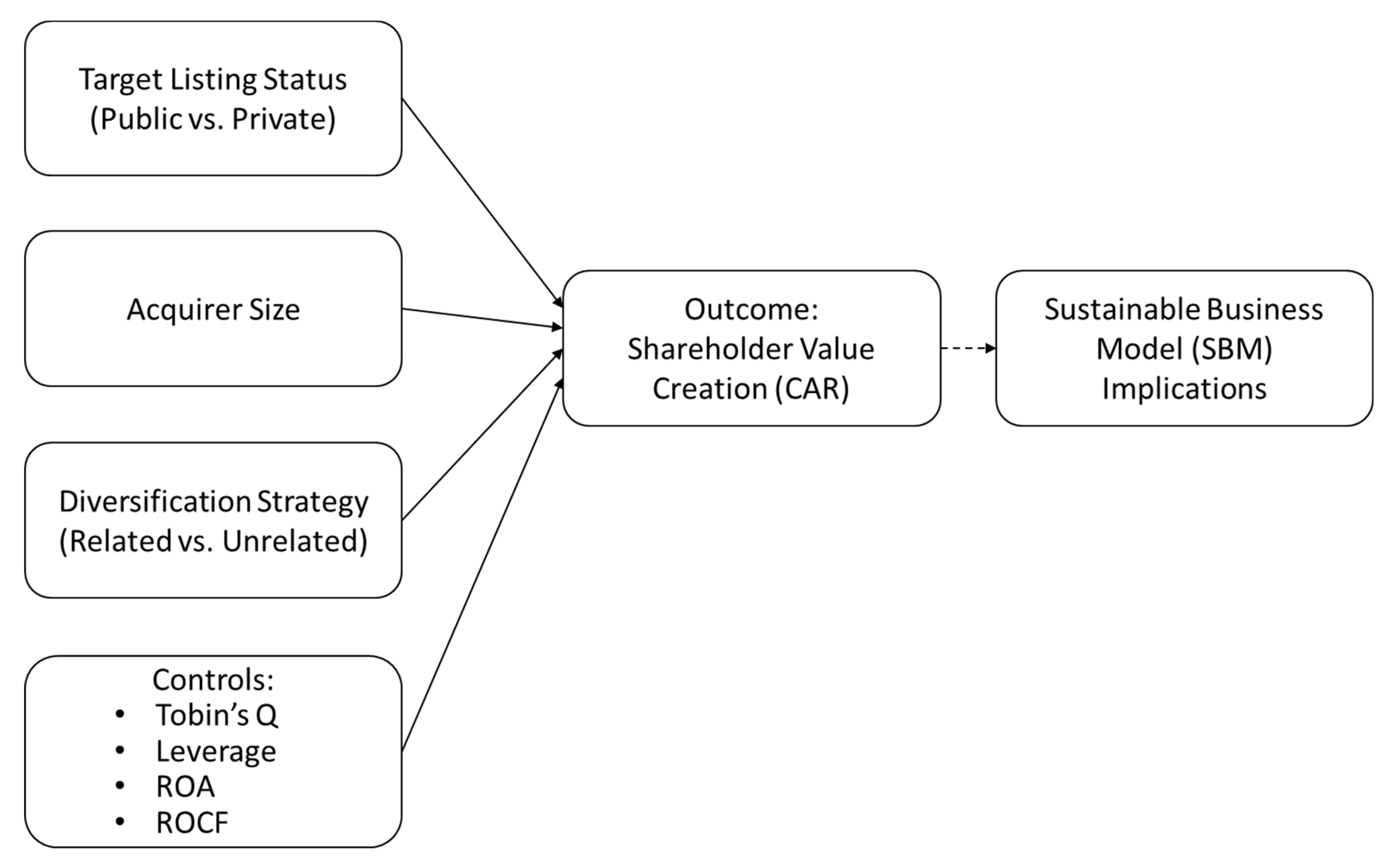

As illustrated in

Figure 1, our conceptual framework visually summarizes the study’s key elements. It shows how the three main factors—target listing status, acquirer size, and deal relatedness (focused vs. diversifying acquisitions)—are hypothesized to influence short-term shareholder value for Korean SME acquirers. This diagram integrates the resource-based, agency, and signaling perspectives, highlighting how these factors not only affect immediate wealth gains but also align with long-term sustainable business model innovation.

Similarly,

Figure 2 presents a flowchart of the research process. This flowchart outlines each major step of the study, from the initial literature review and hypothesis development to data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results. By providing a step-by-step overview,

Figure 2 helps illustrate how the research was conducted and how the hypotheses will be tested in the context of Korean SME M&A transactions.

3. Methodology

We analyze short-term market reactions to M&A announcements using standard event-study techniques and multivariate regressions, and we connect these reactions to medium-term operating outcomes. The event windows are chosen to capture (i) the immediate announcement effect (CAR(−1,+1)), (ii) short-horizon digestion and potential under/over-reaction (CAR(−1,+10)), and (iii) symmetric pre- and post-announcement dynamics (CAR(−10,+10)).

3.1. Research Hypotheses

Grounded in the theoretical framework, we test three hypotheses about M&A outcomes in Korean SMEs:

H1. Acquisitions of privately held (unlisted) targets yield higher cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) for acquirer shareholders than acquisitions of publicly traded targets.

H2. Smaller acquirers experience higher CARs around M&A announcements than larger acquirers; this size effect is expected regardless of target listing status.

H3. Diversifying acquisitions (entries into new industries) generate higher CARs than focused, within-industry acquisitions. Boundary condition: any diversification-related gains should be stronger when the new business is related (capability-complementary) and weaker or absent for unrelated expansions.

These hypotheses map to the paper’s three strategic dimensions: target listing status (H1), acquirer size (H2), and deal scope/relatedness (H3). We evaluate them with an event study and regression analysis as detailed below.

3.2. Data Sources and Sample Selection

Our setting is M&A announcements by non-financial KOSDAQ-listed firms in South Korea during 2016–2020. We begin with the LSEG (London Stock Exchange Group, London, UK) Workspace database, which records a broad universe of global M&A events. From an initial 276,090 announcements worldwide, we apply the following filters to obtain the final sample relevant to our scope:

Market filter: retain transactions with KOSDAQ-listed acquirers (exclude non-KOSDAQ deals).

Industry filter: exclude acquirers or targets in the financial sector to focus on industrial and high-tech SMEs.

Completion filter: remove withdrawn or rumored announcements to ensure reactions correspond to consummated M&A.

Data-availability filter: drop cases lacking required stock price or financial statement data.

After filtering, the final sample comprises 155 M&A events involving KOSDAQ-listed, non-financial acquirers. Each event is aligned on t = 0, the first public announcement date. Daily stock prices and firm-level financials come from FnGuide; prices and the KOSDAQ Composite Index are adjusted for splits and dividends.

3.3. Variables and Measures

Unless noted otherwise, firm characteristics (e.g., ROA (Return on assets), leverage, Tobin’s Q) are measured at the fiscal year-end prior to the announcement (t − 1), consistent with event-study practice. We note that such snapshots may not fully capture very short-run trends immediately preceding the deal. Data treatment: All continuous variables (including CARs and financial ratios) are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers.

Dependent Variable

Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CAR): ARs are computed via the market-adjusted model using the KOSDAQ index as the benchmark, and then cumulated over:

CAR(−1,+1) (one day before to one day after), CAR(−1,+10) (one day before to ten days after), and CAR(−10,+10) (ten days before to ten days after).

Independent Variables

Firm Size (LnSize): Natural log of acquirer market capitalization (common + preferred) at t − 1. We include LnSize to capture the well-documented size effect in M&A; smaller acquirers often earn higher announcement returns [

18].

Tobin’s Q: Market value of equity (common + preferred) divided by book value of assets at t − 1, proxying for growth opportunities. Prior work links higher Q to more favorable M&A announcement returns [

30].

Debt Ratio: Total liabilities/total assets at t − 1. Leverage can constrain value-creating investment [

31] but also impose discipline [

22]; controlling for leverage allows for both channels.

Return on Assets (ROA): Net income/total assets at t − 1, capturing profitability. More profitable, well-managed acquirers tend to execute deals more effectively and are often viewed more favorably by investors [

7].

Return on Operating Cash Flow (ROCF): EBITDA/total assets at t − 1, measuring operating efficiency and internal cash generation. In the free-cash-flow view, abundant cash with limited opportunities can spur value-destroying acquisitions; including ROCF allows us to test that prediction [

18].

Size tier (Size_Dummy): Indicator = 1 if the acquirer’s market cap is below the KOSDAQ 25th percentile at t − 1 (small), 0 otherwise. This isolates the discrete effect of being “small,” complementing the continuous LnSize metric [

18]. For transparency, the overall 25th-percentile threshold in our sample corresponds to approximately KRW 67 billion in market capitalization (median across 2016–2020).

Diversification (Diver_Dummy): This variable is a binary indicator that classifies M&A deals based on industrial fit. It is set to 1 if the acquirer’s and target’s primary SIC industries differ at the 3-digit level, classifying the deal as a diversifying acquisition; otherwise, it is set to 0, indicating a focused acquisition. While we acknowledge that strategic relatedness is best viewed as a continuous spectrum, this binary proxy provides a tractable approximation for the scope of this study. It is important to note that the 3-digit SIC classification is a relatively coarse proxy for relatedness. We suggest that future research could use more granular, continuous similarity metrics (such as text-based similarity) as a natural extension, as further elaborated in the Limitations section.

Target type (listing status): We encode target type with two indicators and an omitted base to avoid multicollinearity:

- −

Public_Dummy = 1 if the target is publicly traded, 0 otherwise;

- −

Private_Dummy = 1 if the target is privately held, 0 otherwise;

- −

Reference category: subsidiary targets (omitted baseline).

Prior research shows acquirer returns differ systematically by target type (typically higher for private/subsidiary, lower or neutral for public) [

30].

Model Design

Estimation window. Normal (benchmark) returns for the market-adjusted model are estimated over trading days −150 to −30 relative to t = 0, using the KOSDAQ index as the market proxy. This window provides a sufficiently long baseline while avoiding contamination by event-related information.

Specification and inference. We estimate multiple regressions in which CAR over each event window is the dependent variable, and the key regressors are target type, acquirer size, and diversification, with firm fundamentals as controls. All models are estimated with heteroskedasticity-robust (Huber–White) standard errors. Notation follows.

Yi = α + Xi′β + εi, where Yi is the acquirer’s CAR, Xi includes deal and firm characteristics (e.g., LnSize, Size_Dummy, Diver_Dummy, Public_Dummy, Private_Dummy, Tobin’s Q, Debt Ratio, ROA, ROCF), and εi is the error term. As a robustness check, we re-estimate models with standard errors clustered by acquirer and, alternatively, by 2-digit industry; inferences are unchanged. We also include coarse 2-digit industry fixed effects in robustness specifications, with similar results.

Model 1: Overall Impact without Target Listing Status Separation

This model assesses the influence of the independent variables on CARs without differentiating based on the target firm’s listing status.

Model 2: Impact Considering Target Listing Status

This model includes dummy variables for the target firm’s listing status to examine their specific effects on CARs.

Event Windows:

CAR(−1,+1): Captures immediate market reaction to the M&A announcement.

CAR(−1,+10): Measures short-term effects post-announcement.

CAR(−10,+10): Assesses both pre-announcement anticipation and post-announcement effects.

Statistical Analysis:

One-Sample t-tests: Conducted to determine if the mean CARs are significantly different from zero, indicating a market reaction to the M&A announcement.

Independent Two-Sample t-tests: Used to compare CARs between different groups (e.g., small vs. large firms, diversifying vs. focused acquisitions) to assess the impact of specific variables.

Multiple Regression Analysis: Applied to test the hypotheses and identify factors significantly affecting CARs, controlling for other variables.

By incorporating these variables and models, the study aims to comprehensively analyze the factors influencing the acquiring firm’s shareholder wealth in M&A transactions. The findings will contribute to understanding how strategic M&A decisions affect sustainable business model optimization.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

This section presents the descriptive statistics of the sample used in the study, providing an overview of the key variables and characteristics of the acquiring firms and the M&A transactions analyzed.

4.1.1. Sample Composition

The final sample consists of 155 M&A events involving non-financial firms listed on the KOSDAQ market between 2016 and 2020. The distribution of the sample based on the target firm’s listing status is as follows:

Public Targets: 39 transactions (25.2%);

Private Targets: 68 transactions (43.9%);

Subsidiary Targets: 48 transactions (30.9%).

This distribution indicates that acquisitions of privately held firms and subsidiaries constitute the majority of M&A activities among KOSDAQ-listed firms in the sample period.

4.1.2. Descriptive Statistics of Variables

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the key variables used in the analysis, including both dependent and independent variables.

The mean CAR(−1,+1) is 2.40%, indicating that, on average, acquiring firms experience a positive abnormal return around the M&A announcement. The range of CAR(−1,+1) varies from −8.50% to 15.20%, suggesting variability in market reactions to different M&A announcements. CAR(−1,+10) has a higher mean of 3.58%, implying that positive abnormal returns extend into the short-term post-announcement period. The average natural logarithm of market capitalization is 25.684. Because LnSize is the natural log of market capitalization measured in KRW (not thousands), 25.684 implies an average market capitalization of approximately KRW 143 billion (=exp(25.684)). The observed LnSize range (23.5–28.2) maps to market caps of roughly KRW 16 billion to KRW 1766 billion.

4.1.3. Correlation Matrix

Table 2 displays the correlation coefficients among the key variables to assess potential multicollinearity issues and understand the relationships between variables.

CAR(−1,+1) is negatively correlated with LnSize (−0.220), significant at the 1% level, suggesting that smaller firms tend to experience higher abnormal returns, supporting Hypothesis 2. Positive correlations between CAR(−1,+1) and Tobin’s Q (0.150) and ROA (0.180) indicate that firms with higher growth opportunities and profitability may achieve better M&A outcomes. Size_Dummy is strongly negatively correlated with LnSize (−0.650), as expected, since the dummy differentiates between small and large firms based on size. ROA and ROCF have a strong positive correlation (0.750), reflecting that profitable firms often have strong operational cash flows. Low correlations among other independent variables suggest minimal multicollinearity concerns, allowing for reliable regression analysis.

4.2. Main Regression Results

We estimate ordinary least squares (OLS) models for (i) announcement-period cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) as the short-term outcome and (ii) post-merger operating cash-flow returns (ROCF) over Years 1–2 as the longer-term outcome. All specifications include standard firm-level controls (Tobin’s Q, leverage, ROA), year fixed effects, and heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) are below conventional thresholds, indicating no material multicollinearity. Robustness with 2-digit industry fixed effects yields materially similar estimates.

4.2.1. Announcement-Period Abnormal Returns (Short-Term CAR Results)

We first verify that there was no significant pre-announcement run-up, which is critical for establishing the validity of event studies. Specifically, the Cumulative Abnormal Return (CAR) for the pre-event window, CAR(−10,−1), is minimal, recording a mean of 0.15% with a t-statistic of 0.30 (

Table A1). Because this t-statistic falls well below conventional significance thresholds, the mean abnormal return is statistically indistinguishable from zero, thereby confirming that abnormal returns were appropriately concentrated at the announcement date.

Table 3 reports Model 1, which relates CAR to firm fundamentals, acquirer size, and diversification. For CAR(−1,+1), the coefficient on LnSize is negative and highly significant; economically, an estimate of −0.0085 implies that a one-unit increase in log size is associated with roughly −0.85 percentage points lower abnormal return in the immediate window. The small-acquirer indicator (Size_Dummy) is likewise negative and significant, reinforcing the size effect (H2). Tobin’s Q and ROA enter positively and significantly, consistent with markets rewarding bidders that exhibit strong growth opportunities and profitability at baseline. By contrast, Debt Ratio, ROCF, and the diversification indicator are not statistically significant. Across the longer windows (−1,+10) and (−10,+10), coefficients generally attenuate and lose significance, consistent with announcement effects being concentrated in the immediate window.

Firm Size (LnSize):

- ○

The coefficient of LnSize for CAR(−1,+1) is −0.00849, significant at the 1% level.

- ○

This negative relationship indicates that larger firms experience lower abnormal returns around M&A announcements.

- ○

This finding supports Hypothesis 2, suggesting that smaller firms gain more from M&A activities in terms of immediate market reactions.

Tobin’s Q:

- ○

The coefficient for CAR(−1,+1) is 0.0018, which is positive and significant at the 5% level.

- ○

This implies that firms with higher growth opportunities (higher Tobin’s Q) achieve higher abnormal returns.

ROA (Return on Assets):

- ○

The coefficient for CAR(−1,+1) is 0.00883, positive and significant at the 5% level.

- ○

This indicates that more profitable firms receive better market reactions to M&A announcements.

Size_Dummy:

- ○

The coefficient for CAR(−1,+1) is −0.01218, negative and significant at the 1% level.

- ○

This reinforces the negative effect of firm size on abnormal returns, consistent with Hypothesis 2 (smaller acquirers see greater gains).

Adjusted R2 and F-Value:

- ○

The adjusted R2 of 0.635 indicates that approximately 63.5% of the variance in CAR(−1,+1) is explained by Model 1.

- ○

The F-value of 39.03 is high and statistically significant, confirming the overall significance of the regression.

Model 2 extends the analysis by incorporating the target firm’s listing status as explanatory variables (Public and Private target dummies, with Subsidiary targets as the omitted reference category).

Table 4 below presents the regression results of Model 2.

Tobin’s Q and ROA:

- ○

Tobin’s Q remains positive and significant for CAR(−1,+1), underscoring the importance of growth opportunities for value creation.

- ○

ROA is also positive and significant, suggesting that more profitable acquirers receive stronger positive market reactions.

Diver_Dummy:

- ○

The coefficient on the diversification dummy remains positive but insignificant, suggesting that diversifying versus focused deals does not have a strong effect on CARs when target listing status and other variables are taken into account.

Adjusted R2 and F-Value:

- ○

The adjusted R2 is 0.632 (very similar to Model 1), indicating a good overall fit for CAR(−1,+1).

- ○

The F-value of 30.19 is statistically significant, confirming that Model 2 is jointly significant (as a whole) despite the addition of several insignificant individual predictors.

Longer Event Windows:

- ○

Similarly to Model 1, no variables are significant for the longer windows CAR(−1,+10) or CAR(−10,+10). This reinforces that the market reaction is concentrated around the announcement date, with little sustained abnormal movement afterward.

Table 4 augments Model 1 with target-type indicators—Public_Dummy and Private_Dummy—using Subsidiary targets as the omitted reference category to avoid the dummy-variable trap. Neither public- nor private-target coefficients differ significantly from the subsidiary baseline once acquirer characteristics are controlled, providing no multivariate support for H1 in this sample. The size results remain robust (negative and significant for LnSize and Size_Dummy), and Tobin’s Q and ROA remain positive and significant. As in Model 1, the diversification indicator is not significant, offering no support for H3 in announcement-period returns.

Overall, these estimates indicate that who the acquirer is—in particular, its size and fundamentals—matters more for immediate market reactions than what is acquired (target listing status or a diversifying label). Accordingly, we treat H2 as supported, while H1 and H3 are not supported in multivariate tests; we therefore avoid drawing positive inferences from their non-significant coefficients. Consistent with our robustness checks, extended windows (CAR(−1,+10) and CAR(−10,+10)) do not yield significant effects for the key variables, reinforcing that announcement reactions should not be conflated with longer-run value creation.

4.2.2. Post-Merger Operating Performance (Long-Term ROCF Results)

To connect short-term expectations with realized outcomes, we complement the CAR analysis with post-merger operating performance over Years 1–2 using ROCF (EBITDA/Assets). This approach assesses whether announcement-period reactions are borne out in operating improvements.

To complement the short-term market-based analysis, we examine long-term operating performance using ROCF (EBITDA/Assets) over Years 1–2 post-merger.

Table 5 reports subgroup means, and

Table 6 reports OLS regressions with ROCF as the dependent variable.

Three results stand out. First, the size effect reverses in operating outcomes: the Small-acquirer dummy is negative and statistically significant, indicating that larger acquirers achieve higher post-merger ROCF over Years 1–2. Thus, while smaller firms are rewarded at announcement (agility, focus), resource depth and integration capacity matter for sustaining operating improvements. Second, target listing status shows no robust long-run effect: the Private-target indicator is small and insignificant after controls, implying that any unadjusted mean differences do not persist in ROCF. Third, diversification is associated with weaker operating performance: the Diversification dummy is negative and marginally significant, consistent with integration complexity and strategic misalignment attenuating efficiency gains in unrelated expansions. The attenuation of the size effect in ROCF is consistent with execution frictions—smaller acquirers face tighter resource constraints and higher integration complexity—which can blunt operating improvements despite positive announcement reactions (see Managerial Implications).

Controls behave as expected: pre-M&A ROCF and ROA load positively (capability and profitability facilitate integration), while leverage loads negatively (financial constraints hinder improvement). Overall, the short-term and long-term evidence together indicate that announcement gains do not automatically translate into superior operating performance. The size effect flips between horizons, listing status matters little over the medium term, and diversification’s costs become more visible in operating metrics—patterns that align with our sustainability framing: enduring value creation hinges on integration capacity, financial discipline, and strategic fit.

4.3. Robustness Test and Endogeneity Test

4.3.1. Robustness Test

To validate the reliability of our main findings and ensure that the results are not driven by model specifications or sample characteristics, we conducted several robustness tests. These tests include alternative model specifications, different event windows, subsample analyses, and checks for multicollinearity and heteroskedasticity. To address concerns about model specification, we also estimate abnormal returns using a market-model approach. As shown in

Appendix A,

Table A2, the CAR(−1,+1) remains positive and statistically significant, while CARs over longer or shifted windows (e.g., CAR(0,+5), CAR(−5,+5)) are not significant. These results are directionally consistent with our main findings using the market-adjusted model.

Alternative Event Windows

We assess sensitivity to event-window choice by re-estimating regressions on CAR(0,+5) and CAR(−5,+5).

Announcement effects are highly concentrated and quickly dissipating, appearing significant only within the immediate window CAR(−1,+1). Consistent with this pattern, no variables are statistically significant in the longer or shifted windows. Specifically, the size effect is statistically significant only in CAR(−1,+1), and it is not significant in CAR(0,+5) or CAR(−5,+5) (

Table 7).

Subsample Analyses

To further test the robustness of our results, we conducted subsample analyses by dividing the sample based on certain criteria and re-estimating the regression models. We split the sample into two groups based on the median value of the Return on Assets (ROA):

High-Profitability Group: Firms with ROA above the median.

Low-Profitability Group: Firms with ROA at or below the median.

Table 8 presents the regression results for these two subsamples. The results for both groups are consistent with the main findings. LnSize and Size_Dummy remain negatively and significantly related to CAR(−1,+1) in both high- and low-profitability subsamples, reinforcing the conclusion that smaller firms experience higher abnormal returns around acquisition announcements. The coefficient for Tobin’s Q is positive in both subsamples but only significant in the high-profitability group (at the 10% level), suggesting that growth opportunities are more valued by the market in firms with higher profitability.

We also analyzed subsamples based on the target firm’s listing status to investigate whether the impact of acquirer size varies across different types of targets.

Table 9 reports separate regressions for acquisitions of public targets, private targets, and subsidiary targets. Across all target-type subsamples, the negative and significant relationship between acquirer size (LnSize) and CAR(−1,+1) persists, confirming the robustness of the firm size effect irrespective of the target firm’s listing status. The Size_Dummy is also negative and significant in all cases, consistent with the idea that the smallest acquirers realize the highest announcement gains. The coefficient for Tobin’s Q is positive and significant at the 10% level for the subsidiary-target subsample, suggesting that growth opportunities are particularly valued when acquiring subsidiaries.

Finally, to ensure that multicollinearity does not distort our regression estimates, we calculated the Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) for all independent variables. The VIF values for all variables were below 2, well under the common threshold of 10 that indicates serious multicollinearity concerns. This suggests that multicollinearity is not a significant issue in our models. Additionally, we performed the Breusch–Pagan test for heteroskedasticity. The test results indicated the presence of heteroskedasticity in some models. To correct for this, we used robust (heteroskedasticity-consistent) standard errors in all regression analyses. This adjustment ensures that the reported t-statistics and p-values are reliable despite any heteroskedasticity.

4.3.2. Endogeneity Test

Although our results consistently show that smaller acquirers earn higher announcement returns, there could be concerns about endogeneity—particularly regarding the acquirer’s decision to pursue an acquisition and the choice of target. It is possible that unobserved factors influencing the decision to acquire (or the type of target chosen) might also be related to the acquirer’s size, which in turn could bias the estimated effect of size on CAR. To address potential endogeneity, we employed an instrumental variables IV (Instrumental variables) approach using two-stage least squares (2SLS). The instrumental-variable (2SLS) regression results are summarized in

Table 10.

In the IV regression, we treated the acquirer’s size (LnSize) as potentially endogenous.

Table 10 reports the first- and second-stage estimates. We used two instruments for LnSize: (1) the industry average size (the average logged size of firms in the acquirer’s industry), and (2) the acquirer’s own lagged size (LnSize from the prior year). These instruments are chosen under the assumption that they are correlated with the acquirer’s current size but uncorrelated with the idiosyncratic component of the acquirer’s announcement return. The first-stage regression results confirm that both instruments are strongly correlated with the acquirer’s size, with the excluded-instruments first-stage F-statistic comfortably exceeding the Stock–Yogo rule-of-thumb threshold of 10 (indicating strong instruments). Where applicable, a Hansen, J. test (for over-identifying restrictions) shows no evidence that the instruments are correlated with the error term (

p-value is large, failing to reject the null that instruments are valid). Full first-stage diagnostics are reported in

Appendix A,

Table A3.

In the second-stage 2SLS results, the coefficient on acquirer size (LnSize) remains negative and statistically significant, and its magnitude is very similar to the OLS estimate in the baseline model. In other words, after instrumenting for firm size, smaller acquirers still experience significantly higher CAR(−1,+1) than larger acquirers. This suggests that our earlier finding–that acquirer size is inversely related to announcement-period abnormal returns–is not driven by endogeneity. The IV analysis therefore reinforces the conclusion that the negative size effect is robust and not an artifact of omitted variable bias or selection effects in the acquisition decision.

5. Discussion

Announcement-window regressions show that ROCF does not load significantly—a result that reflects a scope mismatch: CAR captures investors’ near-term expectations, whereas ROCF materializes with integration lags and execution risk. It is therefore unsurprising that a cash-flow-based metric is weakly associated with day-0 reactions. Against this backdrop, our findings jointly indicate that acquirer characteristics and strategic alignment shape market responses more powerfully than externally visible deal labels, and they remain broadly consistent with the RBV, agency, and signaling perspectives.

Acquirer size and market reaction. We document a strong, negative relation between size and announcement-period returns: smaller acquirers earn significantly higher CARs than larger ones. This “size effect” is consistent with agency arguments—smaller firms (often with concentrated ownership and closer oversight) are less prone to empire-building and overinvestment—and with RBV logic, where a given target’s resources are proportionally more transformative for a smaller acquirer [

18,

22,

32]. Investors appear to anticipate more agile integration and a larger marginal impact of the deal at a smaller scale.

Target listing status. In multivariate tests, listing status is not significant once acquirer fundamentals and size are controlled. While private-target deals show higher unadjusted means, their incremental contribution disappears after conditioning on who the buyer is. A plausible interpretation is that markets weigh acquirer preparedness and strategic fit more than the target’s public-versus-private label. Put differently, any information or bargaining advantages in private deals are not decisive without the acquirer’s capacity to capitalize on them—a nuance that tempers simple “listing-effect” predictions from signaling or RBV perspectives.

Diversification strategy. We find no significant announcement-period premium for diversifying deals, even if raw means are slightly higher. This is consistent with a cautious view of unrelated diversification: integration complexity, capability misfit, and managerial overconfidence can offset putative scope or coinsurance benefits, echoing the well-documented diversification discount [

33]. In sustainability terms, unrelated acquisitions are value-enhancing only when clear synergies exist and absorptive capacity is sufficient.

Firm fundamentals. Tobin’s Q and ROA are positive and significant in the immediate window: bidders with stronger growth opportunities and profitability receive more favorable reactions. In signaling terms, high-Q or high-ROA acquirers credibly communicate strategic readiness; in RBV terms, such firms possess internal capabilities that raise the likelihood of successful resource integration.

Long-term operating performance. Linking announcements to outcomes, our ROCF analysis over Years 1–2 reveals that announcement gains do not automatically translate into operating improvements. The size effect attenuates—and can even reverse—over the medium term: smaller acquirers that enjoy short-run market rewards do not consistently outperform larger acquirers in ROCF. By contrast, larger buyers—despite muted short-term returns—often maintain or modestly improve ROCF, consistent with scale and integration capacity supporting execution. Listing status shows little durable impact, and diversification is negatively associated with ROCF, suggesting integration frictions in unrelated expansions. Importantly, pre-deal ROCF and ROA remain positive drivers of post-merger performance, underscoring that the same fundamentals investors reward at announcement also help realize operating gains.

Synthesis and implications for sustainability. Taken together, the evidence indicates that who the acquirer is—its size, fundamentals, and ability to integrate—matters more than what is acquired (target label, diversification category). Enduring value creation hinges on strategic fit, financial discipline, and execution quality, which are central to building resilient, sustainable business models.

Robustness and diagnostics. Results are stable across alternative event windows and subsamples; the size effect persists when using alternative size proxies. VIFs are below conventional thresholds, and we use heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors. An IV specification (2SLS) using industry-average size and lagged size supports the main inferences, though instrument exogeneity may be imperfect if industry-wide expectations correlate with announcement returns; we therefore present IV estimates as robustness rather than definitive causal identification, and report first-stage relevance and, where applicable, over-identification tests.

6. Conclusions

This study examines how target listing status, acquirer size, and diversification strategy shape announcement-period returns in Korean SMEs, and then links these reactions to post-merger operating performance over 1–2 years. We find that smaller acquirers consistently earn higher CARs (supporting H2), whereas listing status and diversification do not exhibit significant incremental effects in multivariate tests (no support for H1 or H3). Interpreting these null results conservatively, we avoid inferring positive effects from non-significant estimates. Extending beyond the event window, medium-term ROCF checks show that the short-run size advantage moderates or reverses, highlighting that execution and scale capabilities ultimately govern operating outcomes. Listing status remains largely irrelevant to ROCF, and diversifying deals do not deliver clear operating gains, consistent with integration frictions in unrelated expansions.

These patterns advance M&A research by linking short-term market expectations (CAR) to realized operating outcomes (ROCF) as a pragmatic operationalization of sustainability in the business-model sense. Here, sustainability denotes business resilience and adaptive capacity—the ability to integrate resources, preserve financial flexibility, and maintain competitive position—rather than environmental or social metrics. The evidence also aligns with behavioral signaling: stock-financed private-target deals can be read as confidence signals, whereas equity issuance for public targets may trigger adverse-selection concerns; yet even these channels are ultimately dominated by acquirer quality and fit.

Managerial implications. Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) should prioritize acquisitions that genuinely complement core capabilities, time deals from a position of financial strength, and adequately resource post-merger integration (PMI) so that anticipated synergies materialize. This emphasis on implementation capacity is critical because, while smaller acquirers are often rewarded at the announcement period (CAR) for perceived agility and focus, this short-term market advantage frequently fails to translate into superior medium-term operating outcomes (ROCF) over Years 1–2 post-merger. The attenuation of the size effect in operating performance is consistent with execution frictions: smaller acquirers face tighter resource constraints and higher integration complexity, which can blunt sustained operating improvements. Therefore, realizing long-term, sustainable value hinges on integration capacity and scale (resource depth), not just initial market sentiment. Rather than chasing private targets per se or diversifying for its own sake, managers should articulate—and be able to execute—a clear strategic rationale, specifying how the acquisition augments technology, market access, or profitability. Communicating this rationale improves investor alignment at announcement and critically eases the integration process by clarifying end goals and guiding the commitment of limited resources toward achieving strategic alignment and integration success.

Policy implications (Korea). Regulators and agencies can foster prudent, value-creating SME M&A by reducing procedural frictions, improving access to financing (e.g., guarantees or designated credit lines for SME acquisitions), and diffusing know-how through advisory programs, toolkits for due diligence and integration, and transparent matchmaking platforms that connect qualified buyers and targets. Targeted, time-bound incentives for acquisitions demonstrably tied to innovation, scaling, or “green” transformation can further level the playing field for SMEs operating alongside chaebol-affiliated competitors.

Limitations and future research. While our IV approach helps address endogeneity, it may not fully eliminate bias; future work could exploit plausibly exogenous shocks, alternative instruments, or panel designs for stronger identification. Our context (155 KOSDAQ-listed SMEs, 2016–2020) is specific and includes the onset of COVID-19, which may limit generalizability. Finally, several constructs and measures in our design are simplified or coarse. For instance, we classify diversification with a binary related/unrelated indicator based on 3-digit SIC commonality—a rough proxy for relatedness. Future studies could employ more granular or continuous relatedness measures (e.g., text-based industry similarity metrics) to better capture diversification scope. Similarly, fundamentals are measured at the prior fiscal year-end; alternative proxies like multi-tier size bins or recent quarterly momentum might better capture firm heterogeneity. Extending the post-merger horizon and incorporating ESG indicators would also help assess durable value creation more comprehensively.

In sum, strategic fit and execution quality are decisive: smaller SMEs can create immediate shareholder value through well-aligned deals, but sustained operating improvements depend on integration capacity and financial discipline. Conversely, simply acquiring private targets or diversifying does not ensure success. When chosen and managed judiciously, acquisitions become a tool not only for short-term performance but also for building resilient, adaptable business models.