Political Ideology and Support for Tax-Funded UBI: Political Trust as a Moderation Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Political Ideology and UBI

2.2. Political Trust and UBI

3. Model Specification

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Controls

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, D. South Korea Mulls Universal Basic Income Post-COVID. The Diplomat. 13 June 2020. Available online: https://thediplomat.com/2020/06/south-korea-mulls-universal-basic-income-post-covid/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Banerjee, A.; Niehaus, P.; Suri, T. Universal Basic Income in the Developing World. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2019, 11, 959–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Attitudes towards Universal Basic Income in Korea Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Basic Income Stud. 2025, 20, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Social Spending. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/social-spending.html (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Bidadanure, J.U. The Political Theory of Universal Basic Income. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2019, 22, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees-Jones, A.; D’Attoma, J.; Piolatto, A.; Salvadori, L. Experience of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Support for Safety-Net Expansion. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2022, 200, 1090–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetherington, M. Why Trust Matters: Declining Political Trust and the Demise of American Liberalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, T.J. Political Trust, Ideology, and Public Support for Tax Cuts. Public Opin. Q. 2009, 73, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M.J.; Rudolph, T.J. Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust, and the Governing Crisis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roosma, F.; van Oorschot, W. Public Opinion on Basic Income: Mapping European Support for a Radical Alternative for Welfare Provision. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2020, 30, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlandas, T. The Political Economy of Individual-Level Support for the Basic Income in Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2020, 31, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwander, H.; Vlandas, T. The Left and Universal Basic Income: The Role of Ideology in Individual Support. J. Int. Comp. Soc. Policy 2020, 36, 237–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Moon, K. The Implications of Political Trust for Supporting Public Transport. J. Soc. Policy 2022, 51, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Moon, K. Political Ideology and Trust in Government to Ensure Vaccine Safety: Using a U.S. Survey to Explore the Role of Political Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubello, G. Social Trust and the Support for Universal Basic Income. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2024, 81, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.; Evans, J. Political Trust, Ideology, and Public Support for Government Spending. Am. J. Political Sci. 2005, 49, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.K.; Wan, P.; Hsiao, H.M. The Bases of Political Trust in six Asian Societies: Institutional and Cultural Explanations Compared. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2011, 32, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, D. A Systems Analysis of Political Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, K. The World as a Total System; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Armingeon, K.; Weisstanner, D. Objective Conditions Count, Political Beliefs Decide: The Conditional Effects of Self-Interest and Ideology on Redistribution Preferences. Political Stud. 2021, 70, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Federico, C.M.; Napier, J.L. Political Ideology: Its Sructure, Functions, and Elective Affinities. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 307–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, D.; Valgarðsson, V.; Smith, J.; Jennings, W.; Scotto di Vettimo, M.; Bunting, H.; McKay, L. Political Trust in the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis of 67 Studies. J. Eur. Public Policy 2023, 31, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.; Lee, S.; Ham, J. Human Error Suspected as Hope Fades in Korean Ferry Sinking. The New York Times. 17 April 2014. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/18/world/asia/south-korean-ferry-accident.html (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Choe, S. South Koreans Rally in Largest Protest in Decades to Demand President’s Ouster. The New York Times. 12 November 2016. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/13/world/asia/korea-park-geun-hye-protests.html (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Choe, S. South Korea Removes President Park Geun-hye. The New York Times. 9 March 2017. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/09/world/asia/park-geun-hye-impeached-south-korea.html (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Choe, S. Coddling of ‘Gold-Spoon’ Children Shakes South Korea’s Political Elite. The New York Times. 21 October 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/21/world/asia/south-korea-cho-kuk-gold-spoon-elite.html (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Choe, S. An Overloaded Ferry Flipped and Drowned Hundreds of Schoolchildren. Could It Happen Again? The New York Times. 10 June 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/10/world/asia/sewol-ferry-accident.html (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Choe, S. ‘The Den of Thieves’: South Koreans Are Furious Over Housing Scandal. The New York Times. 23 March 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/23/world/asia/korea-housing-lh-scandal-moon-election.html (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Choe, S.; Yoon, J.; Mozur, P.; Kim, V.; Lee, S.; Young, J. How a Festive Night in Seoul Turned Deadly. The New York Times. 30 October 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/30/world/asia/south-korea-itaewon-crowd-crush-victims.html (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Choe, S. Former President Yoon Suk Yeol of South Korea Is Arrested on New Charges. The New York Times. 9 July 2025. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/09/world/asia/south-korea-arrest-yoon-suk-yeol.html (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Choe, S. In South Korea Vote, Virus Delivers Landslide Win to Governing Party. The New York Times. 15 April 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/15/world/asia/south-korea-election.html (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- McCurry, J. South Korea’s Ruling Party Wins Election Landslide amid Coronavirus Outbreak. The Guardian. 16 April 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/16/south-koreas-ruling-party-wins-election-landslide-amid-coronavirus-outbreak (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Fisher, M.; Choe, S. How South Korea Flattened the Curve. The New York Times. 10 April 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/world/asia/coronavirus-south-korea-flatten-curve.html (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Levi, M.; Stoker, L. Political Trust and Trustworthiness. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2000, 3, 475–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, C.; Park, W.; Lee, Y.; Choi, S.; Kim, Sori. Korean General Social Survey 2003–2021; Sungkyunkwan University: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green: Chelsea, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, B. Aiding Strangers: Generalized Trust and the Moral Basis of Public Support for Foreign Development Aid. Foreign Policy Anal. 2017, 13, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.H.; Richard, S.F. A Rational Theory of the Size of Government. J. Political Econ. 1981, 89, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.; Evans, M.D.R. The Legitimation of Inequality: Occupational Earnings in Nine Nations. Am. J. Sociol. 1993, 99, 75–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, J.S.; Rehm, P.; Schlesinger, M. The Insecure American: Economic Experiences, Financial Worries, and Policy Attitudes. Perspect. Politics 2013, 11, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalit, Y. Explaining Social Policy Preferences: Evidence from the Great Recession. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2013, 107, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, C.; Papadakis, E. A Comparison of Mass Attitudes towards the Welfare State in Different Institutional Regimes, 1985–1990. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 1998, 10, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blekesaune, M.; Quadagno, J. Public attitudes toward welfare state policies: A comparative analysis of 24 nations. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2003, 19, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, I.; Velázquez, F.J. The Role of Ageing in the Growth of Government and Social Welfare Spending in the OECD. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2007, 23, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, S.Y. Women’s welfare attitudes in South Korea. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2025, 34, e12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. Heterogeneity in the Preferences and Pro-Environmental Behavior of College Students: The Effects of Years on Campus, Demographics, and External Factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3451–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, 3rd ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, A.; Dixon, J. Generational Conflict or Methodological Artifact? Reconsidering the Relationship between Age and Policy Attitudes in the U.S., 1984–2008. Public Opin. Q. 2010, 74, 643–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, O.; Jauhiainen, S.; Simanainen, M.; Ylikännö, M. The Basic Income Experiment 2017–2018 in Finland: Preliminary Results; Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: Helsinki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxation on basic income | 679 | 2.77 | 1.15 | 1 | 5 |

| Liberal | 679 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Conservative | 679 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Political trust | 679 | 1.55 | 0.48 | 1 | 3 |

| Social trust | 679 | 2.49 | 0.60 | 1 | 4 |

| Subjective class | 679 | 5.33 | 1.46 | 1 | 10 |

| Economic insecurity | 679 | 3.02 | 0.86 | 1 | 5 |

| Anti-welfare sentiment | 679 | 2.96 | 0.92 | 1 | 5 |

| Age | 679 | 50.58 | 13.46 | 21 | 87 |

| Female | 679 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Income level | 679 | 6.64 | 3.62 | 0 | 21 |

| Education level | 679 | 3.47 | 1.41 | 0 | 7 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| (2) | 0.15 *** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (3) | −0.14 *** | 0.44 *** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| (4) | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (5) | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.09 ** | 1.00 | |||||||

| (6) | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.13 *** | 0.12 *** | 1.00 | ||||||

| (7) | 0.07 * | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.12 *** | −0.09 ** | −0.40 *** | 1.00 | |||||

| (8) | −0.12 *** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09** | 0.03 | 0.09 ** | −0.12 *** | 1.00 | ||||

| (9) | 0.03 | −0.09 ** | 0.18 *** | 0.02 | 0.07 ** | −0.09 ** | −0.01 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |||

| (10) | 0.07 * | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 1.00 | ||

| (11) | −0.08 ** | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.08 ** | 0.23 *** | −0.21 *** | 0.02 | −0.16 *** | −0.34 *** | 1.00 | |

| (12) | −0.05 | 0.10 *** | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.23 *** | −0.11 *** | 0.00 | −0.54 *** | −0.11 *** | 0.37 *** | 1.00 |

| Taxation for Basic Income | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| Coef. | (S.E.) | Coef. | (S.E.) | |

| Liberal | 0.41 | 0.18 ** | 0.60 | 0.62 |

| Conservative | −0.33 | 0.20 * | −1.53 | 0.67 ** |

| Political trust | 0.27 | 0.16 * | 0.13 | 0.25 |

| Liberal x Political trust | −0.12 | 0.37 | ||

| Conservative x Political trust | 0.80 | 0.41 ** | ||

| Social trust | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| Subjective class | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Economic insecurity | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| Anti-welfare sentiment | −0.26 | 0.10 *** | −0.26 | 0.11 *** |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Female | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.16 |

| Income level | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Education level | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| Cut point 1 | −1.04 | −1.35 | ||

| Cut point 2 | 0.34 | 0.05 | ||

| Cut point 3 | 1.72 | 1.43 | ||

| Cut point 4 | 3.57 | 3.29 | ||

| Log likelihood | −1035.39 | −1032.15 | ||

| 32.99 | 38.41 | |||

| Average Marginal Effects | S.E. | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderates | 0.006 | 0.012 | 0.598 |

| Liberals | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.954 |

| Conservatives | 0.036 ** | 0.015 | 0.016 |

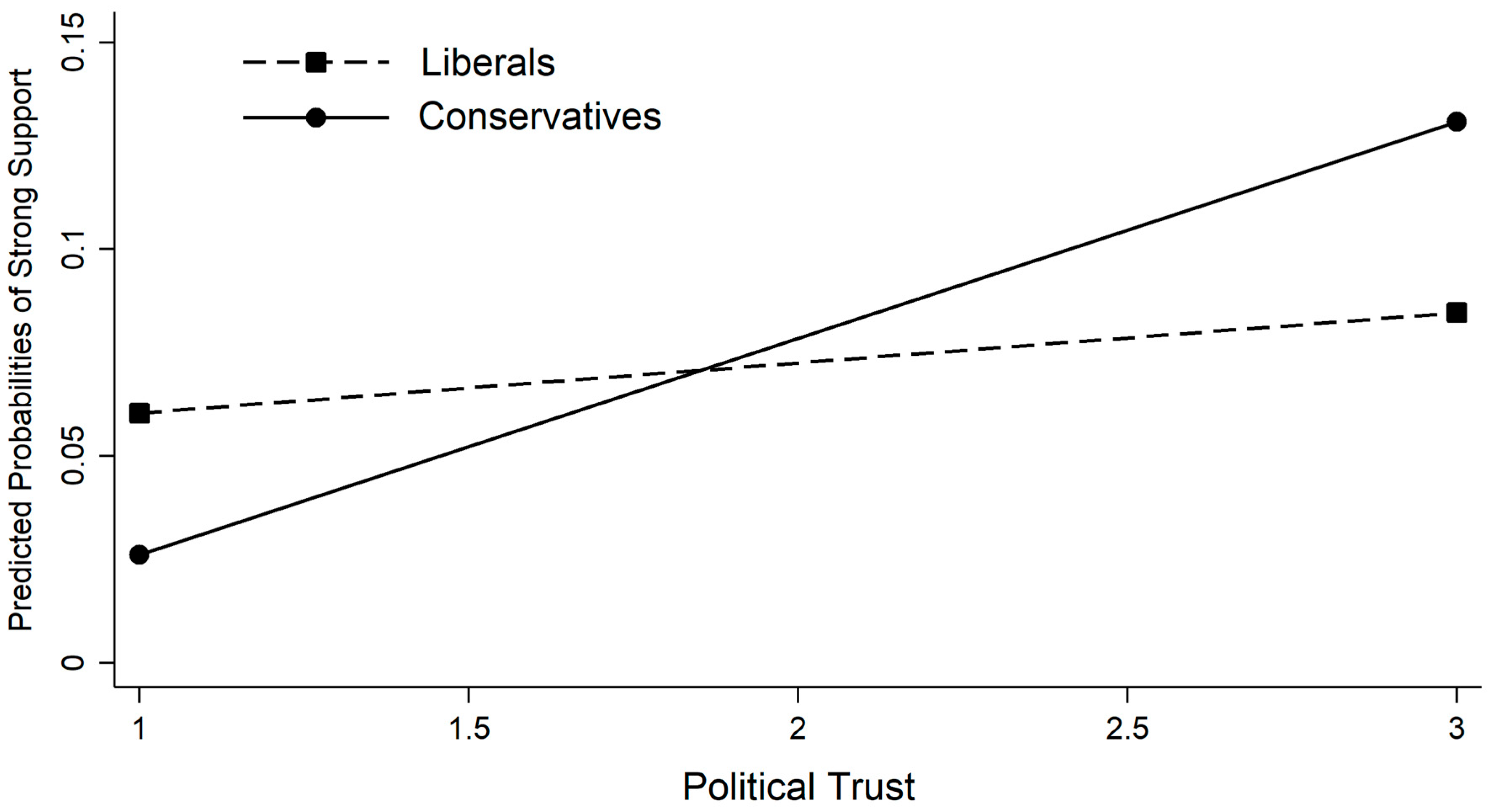

| Political Trust = 1 | S.E. | Political Trust = 3 | S.E. | Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderates | 0.046 *** | 0.011 | 0.059 *** | 0.023 | +0.013 |

| Liberals | 0.072 *** | 0.018 | 0.074 ** | 0.029 | +0.002 |

| Conservatives | 0.022 *** | 0.007 | 0.127 ** | 0.053 | +0.105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moon, K.-K.; Lim, J.Y. Political Ideology and Support for Tax-Funded UBI: Political Trust as a Moderation Mechanism. Systems 2025, 13, 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100846

Moon K-K, Lim JY. Political Ideology and Support for Tax-Funded UBI: Political Trust as a Moderation Mechanism. Systems. 2025; 13(10):846. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100846

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Kuk-Kyoung, and Jae Young Lim. 2025. "Political Ideology and Support for Tax-Funded UBI: Political Trust as a Moderation Mechanism" Systems 13, no. 10: 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100846

APA StyleMoon, K.-K., & Lim, J. Y. (2025). Political Ideology and Support for Tax-Funded UBI: Political Trust as a Moderation Mechanism. Systems, 13(10), 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100846