Balancing E-Commerce Platform and Manufacturer Goals in Sustainable Supply Chains: The Impact of Eco-Friendly Private Labels

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- When the platform adopts a wholesale selling format, the manufacturer will consistently be motivated to pursue the direct channel if the associated costs are relatively low. Launching a direct channel can effectively reduce efficiency losses caused by double marginalization, thereby enhancing the manufacturer’s profitability. However, when the platform employs an agency selling format, the manufacturer’s decision to launch an online direct channel is contingent upon consumers’ relative preferences for EFPLs and direct channels. If consumers have a strong preference for EFPLs, the manufacturer will not launch a direct channel, as this would serve only to exacerbate market competition and diminish profit margins. Conversely, when consumers have a stronger preference for direct channels, the manufacturer will decide to initiate the direct channel if the associated costs are low.

- (2)

- The platform’s choice of selling format is affected by the manufacturer’s channel strategy. The platform’s decision regarding its selling format may vary based on the manufacturer’s different channel strategies and consumer preferences for brands and channels.

- (3)

- The platform’s selling format and the manufacturer’s channel strategies are not always in opposition. When consumers demonstrate a greater preference for the manufacturer’s direct channel over the platform’s EFPL, and the costs for the manufacturer to introduce the direct channel are moderate, opting for an agency selling format can create a mutually beneficial outcome for both the platform and the manufacturer.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Private Label

2.2. Manufacturer Encroachment

2.3. Platform Selling Formats

3. The Model

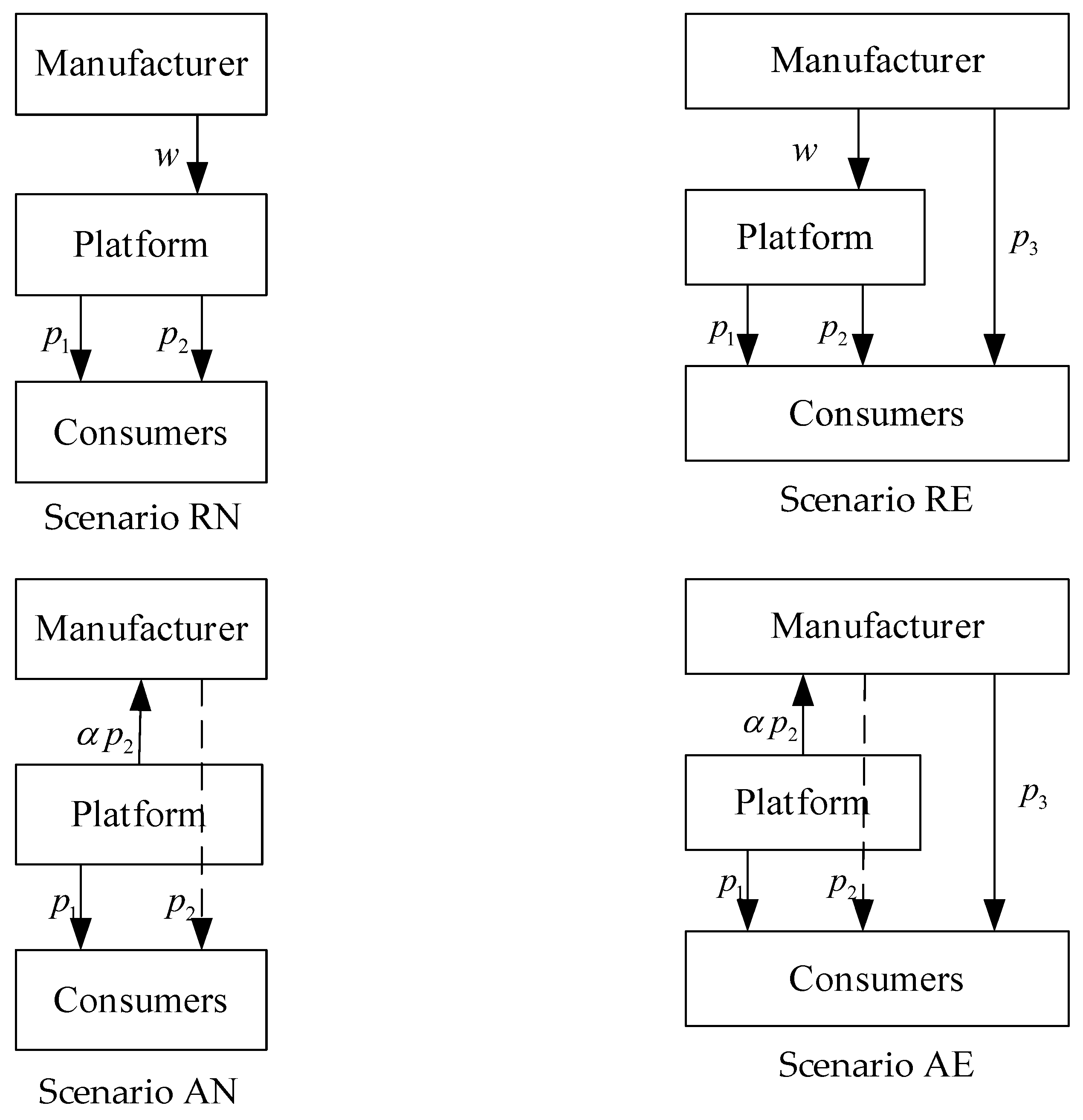

3.1. When the Manufacturer Does Not Introduce an Online Direct Channel

3.2. When the Manufacturer Introduces an Online Direct Channel

3.3. Sequence of Events

4. Equilibrium Results

4.1. The Platform Adopts a Wholesale Selling Format

4.1.1. Scenario RN: Wholesale Selling Without Online Direct Channel

4.1.2. Scenario RE: Wholesale Selling with Online Direct Channel

4.1.3. The Impact of Introducing an Online Direct Channel

- (1)

- When the platform adopts a wholesale selling format and , , , .

- (2)

- When the platform adopts a wholesale selling format and , , , ; when , and when , .

4.2. The Platform Adopts an Agency Selling Format

4.2.1. Scenario AN: Agency Selling Without Online Direct Channel

4.2.2. Scenario AE: Agency Selling with Online Direct Channel

4.2.3. The Impact of Introducing an Online Direct Channel

- (1)

- When and or , ; when , .

- (2)

- When and or , , ; when , .

5. Equilibrium Analysis

5.1. Manufacturer’s Channel Decision

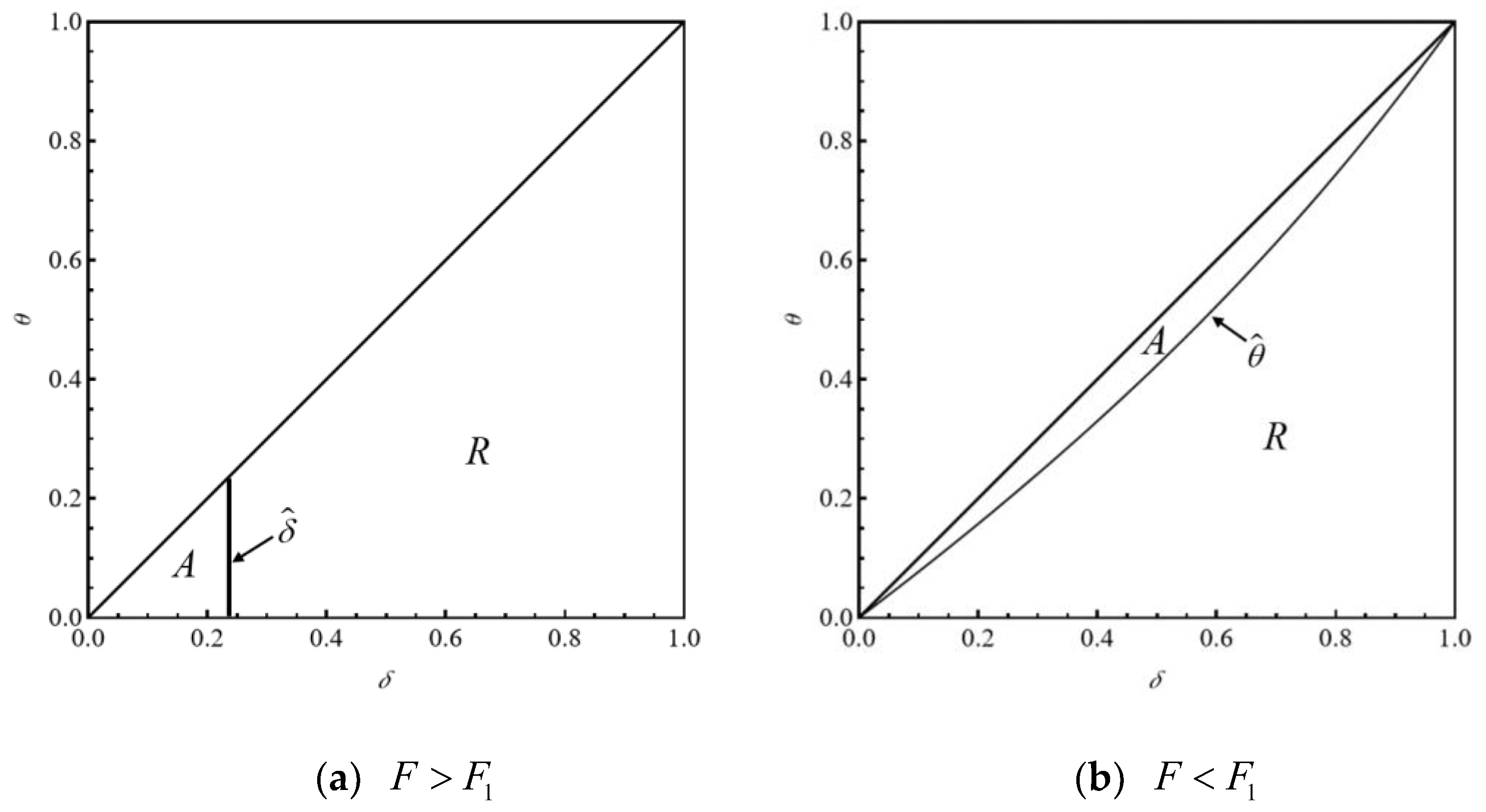

5.1.1. Channel Decision Under the Wholesale Selling Format

- (1)

- Under the wholesale selling format and . If and only if , , the manufacturer launches the online direct channel, where , and when and , .

- (2)

- Under the wholesale selling format and . If and only if , , the manufacturer launches the online direct channel, where , and when and , .

5.1.2. Channel Decision Under the Agency Selling Format

- (1)

- Under the agency selling format and , always holds; the manufacturer does not launch an online direct channel.

- (2)

- Under the agency selling and . If and only if , holds and the manufacturer launches an online direct channel, where .

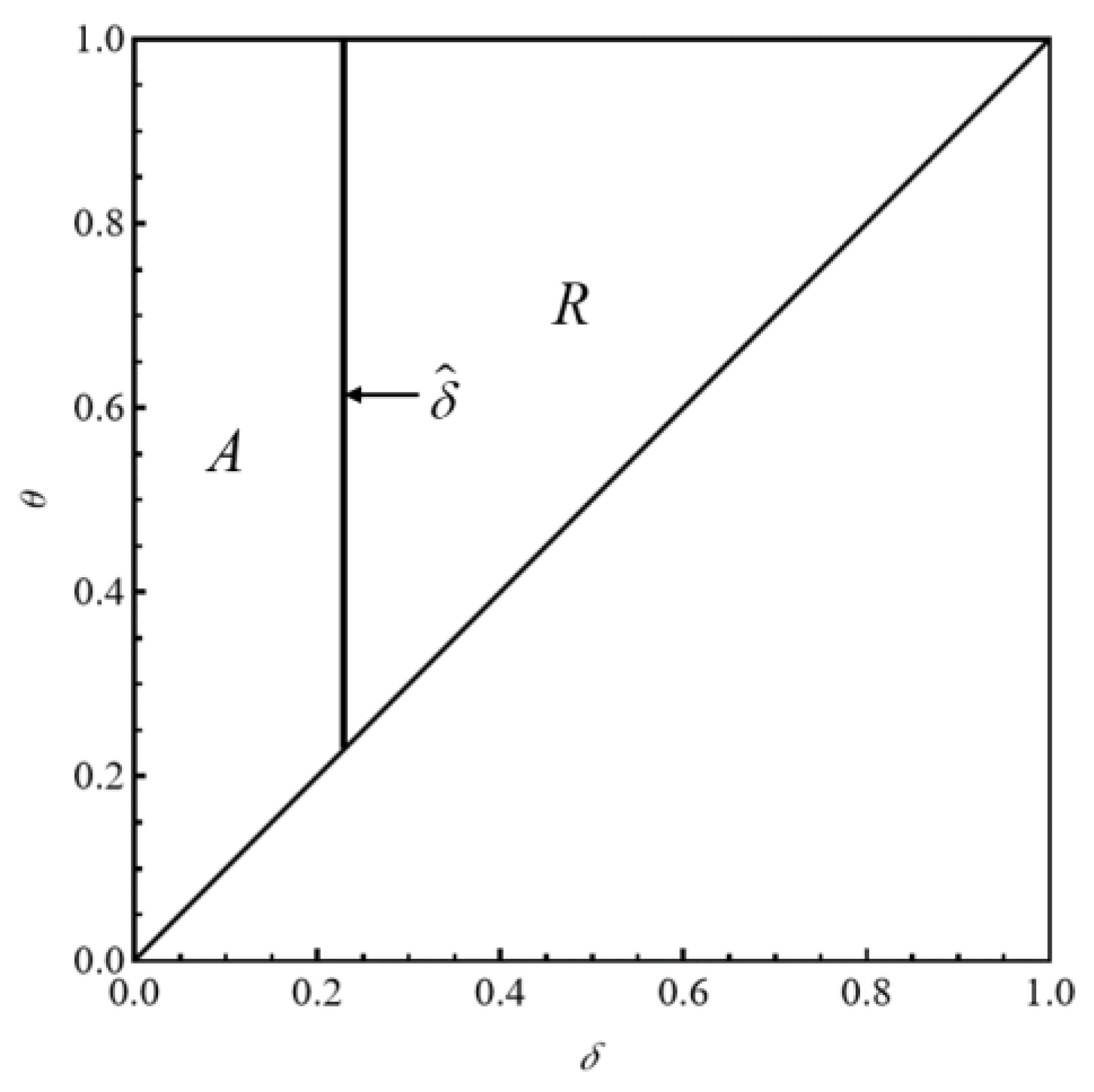

5.2. Decision on the Platform’s Selling Format

- (1)

- When , the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will not introduce the online direct channel. When , the platform adopts the agency selling format (); when , the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will not introduce the online direct channel (); the platform adopts the wholesale selling format. Moreover, .

- (2)

- When , the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will introduce the online direct channel under the wholesale selling format, whereas under the agency selling format, the manufacturer will not introduce the online direct channel. When , the platform adopts the wholesale selling format (); when , the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will not introduce the online direct channel (); the platform adopts the wholesale selling format. Moreover, , .

- (1)

- When , the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will not introduce the online direct channel. When , the platform adopts the agency selling format (); when , the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will not introduce the online direct channel (); the platform adopts the wholesale selling format. Moreover, .

- (2)

- When , the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will introduce the online direct channel under the wholesale selling format, whereas under the agency selling format, the manufacturer will not introduce the online direct channel. Since always holds, the platform will adopt the agency selling format.

- (3)

- When , the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will always introduce an online direct channel, regardless of the selling format it adopts. Since always holds, the platform will adopt the agency selling format.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Findings

- (1)

- Under the platform’s wholesale selling format, the manufacturer is consistently motivated to establish a direct channel if the associated costs are low. The reason is that by selling online directly, the manufacturer can effectively reduce the efficiency loss brought by double marginalization under the wholesale selling format. Conversely, under the agency selling format and with consumers’ preference for the platform’s EFPL over the manufacturer’s online direct channel, the manufacturer will not be able to improve its profitability by selling online directly in any case. This differs from the findings of Li et al., as their study was based on the context of platforms entering into wholesale contracts with manufacturers [13]. However, when the platform adopts the agency selling format, the introduction of an online direct channel by the manufacturer can lead to fierce competition for NBs across different distribution channels, ultimately diminishing the manufacturer’s profitability. Moreover, since consumers prefer EFPLs over the manufacturer’s online direct channel, the introduction of the online direct channel leads to a lower NB price. Facing EFPL competition, the profit loss from the competition effect outweighs the gain from the increased demand brought by the new channel. At this point, the manufacturer’s direct channel always leads to a reduction in profits. When consumers favor the manufacturer’s direct channel over the platform’s EFPL and the fixed costs of establishing the direct channel are low, the manufacturer is likely to introduce an online direct channel. This is because, when consumers prefer the manufacturer’s direct channel over EFPL, the manufacturer can capture greater demand through the online direct channel, resulting in a profit increase that exceeds the losses from channel competition.

- (2)

- When consumers prefer the EFPL over the manufacturer’s online direct channel, the platform expects that the manufacturer will not implement a direct channel with a high cost. The platform chooses the agency selling format when consumer preference for the EFPL is low, and switches to the wholesale selling format when preference for the EFPL is high. This is because, with low consumer preference for EFPL, the substitutability between the EFPL and NB is reduced, leading to weaker competition. Compared to wholesale selling, agency selling can effectively avoid the efficiency reduction caused by double marginalization. When the cost of the manufacturer’s online direct channel is low, the platform anticipates that the manufacturer will launch the channel under the wholesale selling format, but will refrain from doing so under the agency selling format. When consumer preference for the manufacturer’s online direct channel is low, the platform expects the manufacturer to introduce the online direct channel and choose the wholesale selling format. In this case, the platform adopts the wholesale selling format, which can avoid too much competition through the brand collusion effect of the platform channel. When consumer preference for the manufacturer’s online direct channel is high, the platform expects the manufacturer not to introduce the online direct channel and to choose the agency selling format. Through adopting the agency selling format, the platform can improve efficiency by attenuating the double marginalization effect, and avoid a fierce channel competition brought about by the manufacturer’s online direct channel.

- (3)

- When consumers prefer the manufacturer’s online direct channel over the EFPL, the platform expects that the manufacturer will not introduce an online direct channel if it is costly for the manufacturer. The platform adopts the agency selling format when consumer preference for the EFPL is low, while it switches to the wholesale selling format when preference for the EFPL is high. When it is less costly for the manufacturer to introduce an online direct channel, it can be discussed in the context of two cases. The results indicate that the agency selling format is always the optimal choice for the platform, but the intrinsic mechanisms by which the platform determines its selling format are different.

6.2. Managerial Insights

- (1)

- For e-commerce platforms: When a platform introduces eco-friendly private labels, adopting a wholesale selling format helps safeguard its profitability by avoiding direct competition with manufacturers, particularly when consumer preferences for environmentally friendly products are strong. This rationale aligns with the practices of platforms like Amazon.com and JD.com, which prioritize wholesale selling formats while maintaining high-quality private labels. However, when consumer preferences for eco-friendly products are weak, adopting an agency selling format becomes the optimal choice. This approach effectively mitigates efficiency losses caused by the double marginalization effect. To counter the manufacturer’s introduction of an online direct channel, the platform is better off adopting an agency selling format, particularly when consumer preferences for the manufacturer’s direct channel are strong. Additionally, to address the threat of manufacturer entry and to promote eco-friendly private labels, the platform can consider reducing its commission rates appropriately.

- (2)

- For manufacturers: When an e-commerce platform sells eco-friendly private labels alongside the manufacturer’s branded products, the manufacturer must carefully evaluate the decision to establish a direct channel, as this strategy does not always guarantee profitability. In addition to the costs of introducing an online direct channel, manufacturers must also consider the platform’s selling format and consumer preferences for environmentally friendly products. If the platform adopts a wholesale selling format and the cost of establishing a direct channel is low, it is optimal for the manufacturer to introduce the channel. However, when consumer preferences for eco-friendly products are strong, the manufacturer should avoid establishing a direct channel if the platform adopts an agency selling format. In such cases, the manufacturer and platform can achieve a win-win outcome.

- (3)

- For society: On one hand, the potential threat of manufacturers introducing direct channels can incentivize e-commerce platforms to adopt the more efficient agency selling format. If manufacturers can influence platforms to adopt this efficient selling format without actually establishing direct channels, it further avoids the sunk costs associated with direct channel investments, contributing to overall efficiency improvements. On the other hand, the less efficient wholesale selling format facilitates the development of eco-friendly private labels. Thus, when guiding the growth of eco-friendly private labels, governments should balance the efficiency contributions of these two effects. What is more, when consumer acceptance of eco-friendly private labels is initially low, governments can encourage their development through subsidies or other support mechanisms. Simultaneously, attention must be paid to the impact of platform selling formats on overall efficiency.

6.3. Contributions and Future Studies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Available online: http://www.statista.com/forecasts/1283912/global-revenue-of-the-e-commerce-market-country (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Momentum Commerce. Available online: https://www.momentumcommerce.com/amazons-private-label-market-share-shrinks-by-6-year-over-year-in-q1-2024/?trk=public_post_comment-text (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Tencent. Available online: https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20230318A022BC00 (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Simon-Kucher. Available online: https://www.simon-kucher.com/en/insights/how-make-sustainability-growth-driver (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Abhishek, V.; Jerath, K.; Zhang, Z.J. Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 2259–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.C.; Huang, Z.S.; Liu, B. Interacting with strategic waiting for store brand: Online selling format selection. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.P. The agency model and MFN clauses. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2017, 84, 1151–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pun, H.; Zhang, Q. Eliminate demand information disadvantage in a supplier encroachment supply chain with information acquisition. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhong, L.; Nie, J. Quality and distribution channel selection on a hybrid platform. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 163, 102750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ignatius, J.; Song, H.; Chai, J.; Day, S.J. The impact of platform’s information sharing on manufacturer encroachment and selling format decision. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 317, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K. Should competing suppliers with dual-channel supply chains adopt agency selling in an e-commerce platform? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 312, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Agency selling or reselling: E-tailer information sharing with supplier offline entry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 280, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Leng, K.; Qing, Q.; Zhu, S.X. Strategic interplay between store brand introduction and online direct channel introduction. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 118, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, X.; Zhang, R.; Liu, B. OEM’s sales formats under e-commerce platform’s private-label brand outsourcing strategies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 173, 108708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.E. Why retailers sell private labels. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 1995, 4, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, S.; Turcic, D.; Narasimhan, C. National brand’s response to store brands: Throw in the towel or fight back? Mark. Sci. 2013, 32, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, R.; Matsubayashi, N. Premium store brand: Product development collaboration between retailers and national brand manufacturers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 185, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chu, M.; Bai, X. To fight or not? Product introduction and channel selection in the presence of a platform’s private label. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 181, 103373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, H.; Chai, J.; Shi, V. Private label sourcing for an e-tailer with agency selling and service provision. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, J.; Shi, R.; Zhang, J. Does a store brand always hurt the manufacturer of a competing national brand? Prod. Oper. Manag. 2015, 24, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesen, S. Introducing specialist private labels: How reducing manufacturers’ competing assortment size affects retailer performance. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, H.; Gu, X.; Shi, V.; Zhu, J. How to compete with a supply chain partner: Retailer’s store brand vs. manufacturer’s encroachment. Omega 2021, 103, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Guo, S.; Choi, H.Y. Economic and Environmental Implications of Introducing Green Own-Brand Products on E-Commerce Platforms. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K. Promised-delivery-time-driven reselling facing global platform’s private label competition: Game analysis and data validation. Omega 2024, 123, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shopova, R. Private labels in marketplaces. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2023, 89, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, M.; Fatemi Ghomi, S.M.T.; Sajadieh, M.S. The impact of advertising and product quality on sales mode choice in the presence of private label. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 269, 109164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.Y.K.; Chhajed, D.; Hess, J.D. Direct marketing, indirect profits: A strategic analysis of dual-channel supply-chain design. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, A.; Mittendorf, B.; Sappington, D.E.M. The bright side of supplier encroachment. Mark. Sci. 2007, 26, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, K.; Gilland, W.; Heese, H.S.; Swaminathan, J. Boiling frogs: Pricing strategies for a manufacturer adding a direct channel that competes with the traditional channel. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2006, 15, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G. Channel selection and coordination in dual-channel supply chains. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gilbert, S.M.; Lai, G. Supplier encroachment as an enhancement or a hindrance to nonlinear pricing. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2015, 24, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S.; Lee, E. Internet channel entry: A strategic analysis of mixed channel structures. Mark. Sci. 2011, 30, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Pavlin, J.M.; Shi, M. When gray markets have silver linings: All-unit discounts, gray markets, and channel management. M&SOM-Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2013, 15, 250–262. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H.; Gurnani, H.; Geng, X.; Luo, Y. Strategic inventory and supplier encroachment. M&SOM-Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2019, 21, 536–555. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, Q.; He, X. Manufacturer encroachment with advertising. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2020, 91, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Willems, S.P.; Dai, Y. Channel selection and contracting in the presence of a retail platform. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 28, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Qin, Z.; Yan, Y. Effects of online-to-offline spillovers on pricing and quality strategies of competing firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 244, 108376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Strategic choice of sales channel and business model for the hotel supply chain. J. Retail. 2018, 94, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, C.; Cheng, T.E.; Liu, S. Manufacturer encroachment with an e-commerce division. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023, 32, 2002–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zennyo, Y. Strategic contracting and hybrid use of agency and wholesale contracts in e-commerce platforms. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 281, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zennyo, Y. Platform encroachment and own-content bias. J. Ind. Econ. 2022, 70, 684–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiu, A.; Wright, J. Marketplace or reseller? Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwark, Y.; Chen, J.; Raghunathan, S. Platform or wholesale? A strategic tool for online retailers to benefit from third-party information. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; Wei, W. The impacts of market size and data-driven marketing on the sales mode selection in an Internet platform based supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 136, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhao, R.; Liu, Z. Strategic introduction of the marketplace channel under spillovers from online to offline sales. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 267, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, Q.; He, X. Contract and product quality in platform selling. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 272, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaei, A.M.; Taleizadeh, A.A.; Rabbani, M. Marketplace, reseller, or web-store channel: The impact of return policy and cross-channel spillover from marketplace to web-store. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Vakharia, A.J.; Tan, Y.; Xu, Y. Marketplace, reseller, or hybrid: Strategic analysis of an emerging e-commerce model. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Dong, Y. Product distribution strategy in response to the platform retailer’s marketplace introduction. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 303, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.Y.; Tong, S.; Wang, Y. Channel structures of online retail platforms. M&SOM-Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2022, 24, 1547–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, X.; Zhang, Y. The interplay between marketplace channel addition and pricing strategy in an e-commerce supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 258, 108807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etro, F. Hybrid marketplaces with free entry of sellers. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2023, 62, 119–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, P.; Hu, B.; Watanabe, M. Marketmaking middlemen. Rand J. Econ. 2023, 54, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiu, A.; Teh, T.-H.; Wright, J. Should platforms be allowed to sell on their own marketplaces? Rand J. Econ. 2022, 53, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groznik, A.; Heese, H.S. Supply chain conflict due to store brands: The value of wholesale price commitment in a retail supply chain. Decis. Sci. 2010, 41, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.Y.; Luo, H.; Shang, W. Supplier encroachment, information sharing, and channel structure in online retail platforms. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 1235–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, W.; Peng, J.; Wang, J. Game theoretical analysis of incumbent platform investment and the supplier entry strategies in an e-supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 273, 109234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EFPL | Category | Sustainability and Environmental Contributions |

|---|---|---|

| Amazon Aware | Apparel | Made from recycled materials and certified with Organic Content Standard 100, Global Recycled Standard. |

| Beauty | Uses natural ingredients and zero plastic packaging. | |

| Home | Certified by OEKO-TEX for eco-friendly production. | |

| Packaging | Certified with “Compact by Design” to reduce packaging waste and improve transportation efficiency. | |

| JD Jing Zao | Batteries | Mercury-free, eco-friendly batteries. |

| Yoga Mats | Made from eco-safe TPE, no glue used. | |

| Bedding | Sheets certified by GOTS with eco-friendly dyeing. | |

| Packaging | Uses biodegradable materials and reduces carbon emissions through new energy vehicle transportation. |

| Related Study | Selling Format | Manufacturer Encroachment | Private Label | Eco-Friendly Product | Consumer Preferences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang and Zhang [12] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Li et al. [13] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Zennyo [41] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Liu et al. [14] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Etro [52] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Matsui [11] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Wang et al. [23] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| This study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Parameters and Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Consumer valuation of the NB. | |

| Demand for under strategy . | |

| Price for under strategy . | |

| Wholesale price of the NB. | |

| Consumer eco-friendly preference for the EFPL. | |

| Consumer preference for the online direct channel. | |

| Commission rate. | |

| Fixed costs for the manufacturer to establish an online direct channel. | |

| Profit of Firm under Strategy . | |

| Subscript | Denote the EFPL, the NB sold through the platform channel, and the NB sold through the online direct channel, respectively. |

| Subscript | Denote the platform and the manufacturer, respectively. |

| Superscript | Denote the wholesale selling and agency selling. |

| Superscript | Denote the equilibrium results under the conditions of and . |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Cui, X.; Ji, Y. Balancing E-Commerce Platform and Manufacturer Goals in Sustainable Supply Chains: The Impact of Eco-Friendly Private Labels. Systems 2025, 13, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13010036

Liu Z, Cui X, Ji Y. Balancing E-Commerce Platform and Manufacturer Goals in Sustainable Supply Chains: The Impact of Eco-Friendly Private Labels. Systems. 2025; 13(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhiheng, Xiangcheng Cui, and Yuanyuan Ji. 2025. "Balancing E-Commerce Platform and Manufacturer Goals in Sustainable Supply Chains: The Impact of Eco-Friendly Private Labels" Systems 13, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13010036

APA StyleLiu, Z., Cui, X., & Ji, Y. (2025). Balancing E-Commerce Platform and Manufacturer Goals in Sustainable Supply Chains: The Impact of Eco-Friendly Private Labels. Systems, 13(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13010036