Abstract

The new rural collective economy is an important external mechanism for promoting the common prosperity of Chinese farmers. At the same time, the livelihood capital of farmers provides an essential internal support. Achieving an effective match between the two elements is a significant research issue. This article, based on the survey data from 1024 rural households in 43 villages in Zhejiang Province, China, defines the economic functions, social functions, management functions, and cultural functions of the new rural collective economy. The study employs the qualitative comparative analysis method to explore the role of the new rural collective economy in the promotion of the common prosperity of rural households. The necessity analysis shows that the single-factor condition is not the necessary condition for the common prosperity of farmers. However, the adequacy analysis reveals that the linkage and match between the new rural collective economy and the farmers’ livelihood capital can create multiple equivalent pathways for the farmers’ common prosperity. These pathways include the economic function-driven model of the new rural collective economy, the driven model of the high-level livelihoods combined economic functions, the joint model of social function and management functions, the natural capital-driven model, and the joint model of human capital and social capital. Based on these findings, this article proposes targeted governance strategies, including creating pillar industries, strengthening public management services, expanding the scope of social services, and building a coordination mechanism between the new type of rural collective economy and farmers’ livelihood capital.

1. Introduction

The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) concluded that socialism with Chinese characteristics has entered a new era of its development. The Congress set a significant objective as part of the second centenary goal, which focuses on the attainment of common prosperity for all the people of China by the middle of this century. However, compared to urban residents, rural farmers face greater challenges in achieving common prosperity. To meet the goals of rural revitalization and attain common prosperity, it is crucial to objectively assess the current state of agricultural and rural development, and to identify the main obstacles to the common prosperity of farmers and people in the rural areas [1]. Document No. 1 of the Central Committee in 2023 emphasizes that it is necessary to consolidate and improve the achievements of the reform of the rural collective property rights system. This includes building an operating mechanism with clear property rights relations, scientific governance structure, stable operation mode, and reasonable income distribution. The document also advocates for diversified ways to develop a new rural collective economy such as resource contracting, property leasing, intermediary services, and asset participation [2]. These measures underscore the effort and determination of the Chinese government to develop a new type of rural collective economy and to achieve rural revitalization and common prosperity. Zhejiang is the only demonstration area for promoting the construction of common prosperity in China, and its level of rural collective economic development is at the forefront in the country. As of the end of 2022, there were 23,148 new rural collective economic organizations, with total village-level collective assets of 89.01 billion yuan in the province, a total collective economic income of 76 billion yuan, and operating income of 48.5 billion yuan [3]. In 2022, the implementation opinions of the People’s Government of Zhejiang Province on promoting comprehensive rural revitalization with high quality proposed to focus on promoting the integrated reforms to strengthen villages and enrich the people with a rural collective economy as the core, and fully leverage the important role of the new rural collective economy in promoting common prosperity among farmers. Therefore, our survey and analysis of the rural collective economy in Zhejiang Province provide positive valuable insights for promoting rural collective economic reform and achieving common prosperity for farmers in China.

The development of the new rural collective economy is driven by the integration and interaction of high-quality production resources which promote development benefits [4]. Since the founding of New China, the evolution of the rural collective economy can be roughly divided into four stages. In the early stage, from 1949 to 1958, the rural collective economy began to take shape in the form of rural mutual assistance. Subsequently, from 1958 to 1983, the people’s commune system was created on the basis of “three-level ownership with the team as the foundation”. From 1983 to 2004, the rural collective economy turned to the contract responsibility system, marking the beginning of a new stage. Since 2004, the introduction of a land transfer system has opened a new chapter of the rural collective economy [5]. At present, the new rural collective economy relies on large-scale production and effective allocation of labor force, and facilitates the process of urbanization and the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy by promoting the development of healthy labor–capital relations [6]. Even after achieving the comprehensive poverty alleviation in rural areas, the attainment of farmers’ common prosperity is still the core task and foundation of the realization of comprehensive common prosperity. Therefore, it is particularly important to explore the mechanism of the new rural collective economy in promoting the common prosperity of farmers.

The existing research on the new rural collective economy to promote the common prosperity of rural households mainly focuses on the theoretical frameworks, with a notable lack of empirical evidence. Firstly, the new rural collective economy aids farmers in increasing their income through dividends, transfer income [7], and operational income [8]. Secondly, rural collectives play a crucial role in maintaining social stability and improving rural governance [9]. These collectives realize the function of social insurance by expanding service supply and commercial insurance [10]. Additionally, the rural collectives realize the dual power of economy and society by participating in the supply of public goods [11] and also realize the isomorphism of the village’s two committees and collective economic organizations by embedding rural governance [12]. Moreover, rural collectives significantly contribute to the common prosperity of rural households. Yang et al. [13] took the “Wang Jiabian experience” in Shaanxi Province and the “Tangyue model” in Guizhou province as examples, and found that the new rural collective economy plays a vital role in attaining common prosperity by realizing the double effect of the growth of farmers’ market ability and the cohesion of collective power. Furthermore, Yang and Mu [6] believe that it is necessary to promote the two-way balanced and complementary flow of urban and rural resource factors to promote common prosperity.

From the perspective of configuration, the common prosperity of farmers results from the interaction and mutual matching between external factors, such as the new rural collective economy, and internal factors, such as farmers’ livelihood capital level. This ultimately manifests as a complex cause-and-effect relationship caused by different factors. This article integrates four functional conditions of the new rural collective economy and five household livelihood capital conditions to explore the complex path towards the common prosperity of farmers. This study broadens the scope of research around the rural collective economy, especially the verification of the “joint effect” between the rural collective economy and farmers’ livelihood capital. This has significant practical implications for exploring the diversified pathway to achieving common prosperity for rural farmers.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. New Rural Collective Economy

The new rural collective economy is a shared economic model formed by integrating production factors such as labor and capital and utilizing their respective advantages since the reform and opening up, emphasizing the importance of resource integration [14]. Ni et al. [15] believe that the new rural collective economy follows the four principles of clear property rights, complete power, smooth circulation, and strict protection. It achieves collective development through the collective members’ utilization of common resources, democratic management, cooperative operation, and scientific distribution, highlighting the collective development mode supported by the system. Zhao [16] regarded the new rural collective economy as an economic model produced in response to changes in the market economy and the goal of common prosperity under the support of China’s land circulation policy. This has been facilitated by the innovative means of resource and capital transformation, and the transformation of farmers’ identity into shareholders, so as to carry out effective operation and management. Document No. 1 of the Central Committee in 2023 clearly defined the new rural collective economy for the first time and expounded its core characteristics of “clear property rights relationship, scientific governance structure, stable operation mode, and reasonable income distribution” [17]. The new rural collective economy should be compatible with the current rural management system and market economy, releasing productivity and ensuring common prosperity of farmers through collectivization and intensive operation [18].

2.2. Common Prosperity of Rural Households

The academic community’s understanding of the concept of common prosperity has been further developed. For instance, Zhou and Zhang [19] believe that common prosperity is comprehensive prosperity. They contend that, on the one hand, common prosperity is not only the enrichment of material life but also the enrichment of spiritual life. On the other hand, it also refers to the satisfaction of human needs in all aspects and the all-around development of human beings. From the perspective of the new form of socialist civilization, Li [20] pointed out that common prosperity is a general prosperity in which all members of an affluent society have various means of production and means of living to meet their needs for a better life. In this case, everyone has reached an affluent living standard, and the existing gap is reasonable.

For rural households, the common prosperity means fulfilling their growing needs for a better life, including material life needs, spiritual and cultural needs, basic public service needs, and ecological needs for a livable environment [21]. The horizontal dimension of common prosperity of rural households mainly includes economic development level, material living level, and cultural living level [22]. Additionally, some research investigated the level of common wealth among farmers from different dimensions [23].

2.3. The Theoretical Mechanism of the New Rural Collective Economy in Promoting the Common Prosperity of Rural Households

- Economic function. As a typical form of public ownership economy, the rural collective economy not only adapts to the two systems of planned economy and market economy but also effectively plays the market-oriented function of the new rural collective economy under the market economy system. The new rural collective economy has built a support platform for individual economic participants, lowering the threshold to the market, and significantly enhancing their competitiveness in the market and risk resilience. This model gives farmers more rights of speech and more equal participation in the market, thus effectively safeguarding their rights and interests [24]. In addition, based on its advantages in management, the new rural collective economy can effectively cooperate with external market players to introduce capital, technology, and human resources. This cooperation not only promotes the optimization and adjustment of rural industrial structure but also enhances the market competitiveness of rural industries. Additionally, the new rural collective economy can strengthen the self-development power of the countryside as well as promote the rise of new business forms and the expansion of the industrial chain [25]. This economic model has created many jobs in the local and surrounding areas, attracted the return of migrant workers, and provided farmers with more ways to increase their incomes. In this way, the new rural collective economy not only significantly increases the incomes of farmers but also injects new vitality into the rural economy and promotes the sustainable development of the region [26].

- Social function. The new rural collective economy possesses both social and economic attributes [27]. Given its core values of co-creation and sharing, the new rural collective economy carries significant social functions and becomes an important driving force for the development of rural public interests and public welfare undertakings. It plays a key role in improving the comprehensive well-being of rural areas through participating in the improvement of rural infrastructure, ensuring the reliable supply of public services, enriching rural cultural life, and promoting ecological beautification projects [28]. Traditionally, rural public services are largely dependent on government funding. However, the development of a new rural collective economy is bringing about a remarkable transformation. It is able to achieve a major leap from a single “blood transfusion” by the government to “self-hematopoiesis” by the masses, which not only improves the quality of life of farmers but also enhances their sense of happiness and satisfaction.

3. Model Setting, Data Source, and Variable Selection

3.1. Qualitative Comparative Analysis Method

In the research involving the exploration of the factors influencing the new rural collective economy, many scholars tend to adopt the method of regression analysis, which effectively measures the direct influence of various factors on the outcome variables, namely net effect. However, this approach often fails to capture the complex interactions and joint effects that may exist between factors [29]. These interactions can lead to complementarity, where the combined effect of two factors exceeds the sum of their individual effects, a phenomenon often missed by current linear regression models. A thorough understanding of the interactions and joint effects among the influencing factors is essential to fully understand how all factors work together towards the development of common prosperity. In addition, this can also provide more effective ideas for optimizing resource allocation and for formulating development strategies of the new rural collective economy.

The Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), proposed by an American scholar Rangin [30], is a research and analysis method that combines “set theory analysis” and the “case-oriented method”. The QCA method emphasizes that the factors leading to a specific result often exert their influence through mutual combination and dependence, rather than independent action [31]. According to the nature of variables, QCA is divided into csQCA (clear-set qualitative comparative analysis), mvQCA (multi-value qualitative comparative analysis), and fsQCA (fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis). FsQCA has shown its unique applicability in dealing with the problems of category ambiguity and degree uncertainty in the study of the rural collective economy. In this article, the fsQCA module in the FSQCA 3.0 software is used for data processing and analysis [32]. The basic logic and steps are as follows:

First, according to the research purpose and empirical data, the outcome variables and appropriate conditional variables are determined;

Second, data calibration. Based on the theory and case practice, the assignment criteria are established, three meaningful anchors are set for the result variable and the condition variable, and the variables are converted into membership scores of fuzzy sets;

Third, a necessity test. Necessity tests are performed on condition variables in order to test whether there are necessary conditions for a given result;

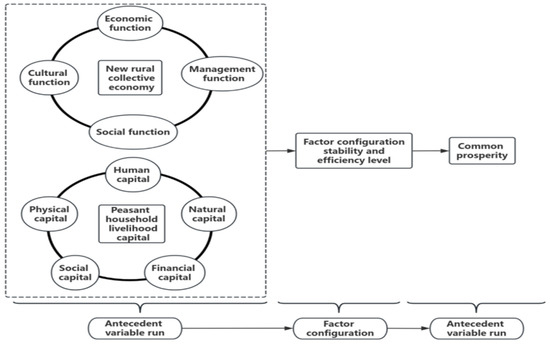

Fourth, configuration analysis. The reliability of the conditional combination generated by the model is tested by two indicators, consistency and coverage, and the reasons for the existence of the resulting configuration combination are evaluated [33]. The configuration analysis frame diagram is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Configuration analysis framework.

3.2. Data Source

This study utilized data from a survey conducted by the research team between July 2023 and September 2023. Before the formal investigation, the research team conducted a preliminary investigation in Zhejiang Province and trained the investigators. During the investigation, the team members used face-to-face interviews and simple sampling methods to learn about the basic situation of farmers’ families, farmers’ views on social development issues, and farmers’ views on the role of the new rural collective economy in increasing residents’ income. The survey covered 46 villages in 35 districts and counties across 9 cities in Zhejiang Province. A total of 55 village-level group questionnaires and 1118 household questionnaires were collected. After excluding the missing samples of the core correlation variables, 1024 samples from 43 villages were retained for analysis. It should be emphasized that to improve the accuracy of the survey, we clearly pointed out in the questionnaire that the new rural collective economy refers to the development by rural collective economic organizations through various channels such as resource contracting, property rental, intermediary services, and participation in operating property. The main management entities include village committees, village-level stock economic cooperatives, stock cooperative companies, and village and town economic cooperatives, among others. The industrial modes of the collective economy include land or property leasing, planting and operation, animal husbandry, agricultural product processing, industrial manufacturing, production service, public service, tourism and leisure industry, e-commerce and logistics, among others.

3.3. Variable Setting

3.3.1. Result Variables

In this article, the outcome variable is the index of common prosperity. The construction of common prosperity needs to start from the perspective of people’s needs. The report of the 20th National Congress of the CPC highlighted that Chinese modernization is the advancement of material civilization and spiritual civilization. Material and spiritual prosperity are the fundamental requirements of socialist modernization [34,35]. Since 2021, many scholars have delved into the evaluation index system of common prosperity, and explored ways to measure common prosperity from multiple dimensions. Liu et al. [36] evaluated common prosperity from the dimensions of overall prosperity and development achievement sharing. Similarly, Wang et al. [21] assessed common prosperity from four dimensions including material wealth, harmonious social life, rich spiritual life, and livable ecological environment. Conversely, Zhang et al. [37] evaluated common prosperity from the dimensions of richness, sharing, and sustainability.

With reference to the evaluation dimension of common prosperity in the existing literature, this article starts from three dimensions of wealth, sharing, and sustainability level. Six secondary indexes are established, including economic income level, spiritual affluence level (wealth level), medical and educational level, pension security level (sharing level), ecological environment level, and public construction level (sustainability level). They are further broken down into twenty-eight tertiary indicators to evaluate the level of common prosperity [38]. The evaluation index system of common prosperity is constructed by using the hierarchical response model, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Evaluation indexes of the common prosperity of farmers.

The reliability and validity of the above data indexes are tested to ensure that the monotony and unidimensional test of the measurement meet the standard. The unidimensional test was passed by the principal component analysis method. The results showed that the Loevinger’s H value of the two primary indicators of relative per capita family income and satisfaction with each physical examination was much lower than 0.30, which did not meet the monotony requirements, so it was deleted in the subsequent model analysis. Table 2 shows the estimation results of household common affluence indicators based on the hierarchical response model; a is the discrimination parameter of the test item, b1~b5 are the cut points for the test item [37]. The results indicate that the values of a range from [0.3, 4] and b ranges from [−4, 4], which are within a reasonable range.

Table 2.

Parameter estimation results of item response theory hierarchical response model.

This article uses the difficulty weighting method to determine the weights of 6 secondary variables, then calculates the common prosperity effect index of farmers, and then calculates the village-level average value as the final result variable. The main reason for using the difficulty weighting method is that the difficulty coefficient represents the probability of the subject passing or reaching a certain response level when the potential ability of the farmer is at a certain level in the GRM model. The gradual increase in the difficulty coefficient reflects that the subject is gradually able to pass the higher level of response level with the increase in potential ability. As an objective evaluation index, it can reflect the differences among the indicators based on the probability of farmers reaching the highest level of each index.

3.3.2. Conditional Variables

When constructing a model, the appropriate conditional variables directly affect the explanatory ability of the model and the ease of interpretation. The simplicity of the model and the reliability of the variables should be comprehensively considered in the selection of the variables. The factors influencing the realization of common prosperity of farmers are mainly divided into two levels. The first is the livelihood capital within farmers which includes farmers’ human capital, material capital, financial capital, natural capital, and social capital, and the second is external environmental factors, that is, the characteristics of the new rural collective economy, including economic functions, social functions, management functions, and cultural functions [39]. In this study, the entropy weight method is used to determine the weights of each index and calculate the fitting values of two types of the condition variables.

- ①

- The function condition variable of the new rural collective economy

In this article, the function condition variables of the new rural collective economy are categorized into economic function, social function, management function, and cultural function. Firstly, the entropy weight method is applied to calculate the functional variables of each farmer, and then the village-level average value is calculated as the indicator of the village-level functional variables. The function condition variable of the new rural collective economy and their weights are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The function condition variable of the new rural collective economy.

- (a)

- Economic function. The rural collective economy is a key way to increase farmers’ income and an important force to promote China’s agricultural modernization [40]. Its economic function is to manage assets and formulate collective economic investment strategies, rather than directly participate in daily business activities [41], with the purpose of promoting rural economic development and improving farmers’ income. This article selects the effect degree of the new rural collective economy on the increase in farmers’ total income, operating income, wage income, and dividend income, and comprehensively measures the economic benefits of the new rural collective economy in promoting farmers’ income growth.

- (b)

- Cultural functions. The cultural function of the new rural collective economy covers the organization’s shape and guides the members’ values, norms of behavior, social identity, and other aspects. It can play a role of cultural guidance in the community, provide members with a broader cultural experience, and at the same time transmit positive cultural values. It is of great significance to form a dynamic and cohesive cultural atmosphere and promote the cultural prosperity of the community. This article selects four function indicators, namely, rural cultural activities, publicity of rural civilization, publicity of rural healthy life, and rural cohesion of spiritual emotions, to measure the influence of the new rural collective cultural functions on the common prosperity of rural households.

- (c)

- Social function. The new rural collective economy plays a fundamental and key role in providing rural public goods and maintaining the spiritual home of the farmers. It does not only realize various social functions, such as providing hardship subsidies, medical assistance, and life services for its members, but also plays the role of social stabilizer through the redistribution of collective net income. This reallocation of resources ensures the basic balance of farmers’ income, especially the rural five-guarantees households, poor families, and disabled people, and provides basic livelihood guarantees for rural low-income people [42]. In this article, five functional indicators are selected to comprehensively measure their contribution to improving farmers’ well-being, including farmers’ hardship subsidies, medical assistance, mutual support for the aged, subsistence relief, and education subsidies.

- (d)

- Management functions. The management function of the new rural collective economy refers to the functions of guiding production, coordinating management, infrastructure construction, and supply of public goods in addition to production and business activities. The capacity for effective organization, coordination, decision-making, and control of matters and resources within the collective economic organization helps to ensure that the collective economic organization can function effectively, adapt to change, improve competitiveness, and achieve sustainable development at the economic and social levels. This article selects three function indicators, including rural infrastructure construction, rural public service, and ecological beautiful countryside construction, to measure the influence of the new rural collective economic management function on farmers’ common prosperity.

- ②

- Livelihood capital condition variable.

At the farmer household level, based on the sustainable livelihood analysis framework proposed by the British Agency for International Development in 2000, livelihood capital is divided into five categories, including natural, human, material, social, and financial capital [43]. Firstly, the entropy weight method is used to calculate the functional variables of each farmer, and then the village-level mean value is calculated as the final livelihood capital condition variable. The specific contents of livelihood capital variables are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Condition variables of farmers’ livelihood capital.

- (1)

- Human capital. As a key factor to measure farmers’ production efficiency and income-generating ability, human capital covers farmers’ knowledge, skills, labor ability, and physical conditions [44,45]. The selected indicators in this article include the education level of the householder, whether there are college students in the family, the burden coefficient of the household labor force, and the health status of the householder.

- (2)

- Material capital. Material capital is the means of production and fixed assets owned by families to maintain livelihoods [46], which can raise production efficiency, improve quality of life, and enhance the ability to resist risks. Therefore, three indicators are selected to measure the material capital of households: whether households have production tools such as larger agricultural machinery (tractors, agricultural tricycles, pesticide sprayers, and water pumps), vehicles and other means of transportation (cars, motorcycles), and housing level.

- (3)

- Financial capital. As an important index to measure the level of funds available to households in production and daily life and the ability to obtain external financing, financial capital has a direct impact on the investment decisions of farmers in agricultural production, technological innovation, education investment, and health protection. Therefore, the logarithm of per capita household income, the proportion of agricultural income, the proportion of operating income, and whether the family has financial assets are selected as the measurement indicators of financial capital.

- (4)

- Natural capital. For most rural families, natural capital refers to the land resources owned by the family [47], which is the basic element of agricultural production. Good natural capital can directly improve the efficiency and quality of agricultural production, thus increasing the income of farmers. In addition, a healthy natural environment is also crucial to maintaining ecological balance and ensuring agricultural sustainability. This part selects whether households contract cultivated land and whether households contract other resources (garden land, forest land, aquaculture water area) as indicators to measure natural capital.

- (5)

- Social capital. Social capital reflects the family’s position in the social relationship network and the range of social resources available, including the interaction and communication frequency of family members, as well as the closeness of their connections with all sectors of society [48]. This article chooses whether there are close families (families with various forms of mutual assistance frequently) and whether some family members work for bosses, doctors, teachers, staff of government departments or public institutions as indicators to measure social capital [49].

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Necessity

When using the fsQCA method, each result variable (the common affluence index) and the condition variable are treated as a set, respectively, and a membership score is assigned to each sample in the set. The process of calibration is the process of assigning set membership scores to samples [50]. According to the conventional calibration method of fsQCA research, the direct calibration method is used in this study to convert the raw data into fuzzy-set membership scores, whose range is between 0 and 1. By setting three key anchor points of complete subordination, intersection, and complete non-subordination, the variable is transformed into a fuzzy-set membership score. This process describes the degree to which the case is inside or outside the set. According to the calibration method of Fiss [51], for the four functional variables of the new rural collective economy, the quantile values of 95%, 50%, and 5% of each variable data are used as calibration anchors, respectively. For each variable, 5% of its quantile is calibrated to not belong to the set at all (0), 50% of its quantile is calibrated to the intersection of the set (0.5), and 95% of its quantile is calibrated to belong entirely to the set (1). It reflects more accurately the relative importance of the variable in different contexts. The fsQCA3.0 software was used to calibrate the data.

Then, a necessity test is conducted on the condition variable (including its non-set) to explore whether the necessary conditions for a particular outcome exist. The necessary condition does not ensure that the result will necessarily occur, but if the outcome does occur, the condition must be present. The key index to evaluate the necessary conditions is the consistency level. If the consistency level of the condition is greater than 0.9, it is considered as the necessary condition to achieve the result [52]. As shown in Table 5, the consistency level of all conditions does not reach the threshold of 0.9, indicating that none of the nine conditions is necessary for the realization of the result variable. Nevertheless, the consistency and coverage of these condition variables showed a relatively high level, suggesting that they can explain the occurrence of the results to some extent. Given that the effect of the development of the new rural collective economy in promoting the common prosperity of farmers is the result of multiple factors, further analysis of the combination of conditional variables will help to obtain more in-depth insights.

Table 5.

Univariate necessity analysis.

4.2. Conditional Configuration Analysis

This article investigates the driving mechanism of five antecedent conditions of farmers’ livelihood capital and four antecedent conditions of the new rural collective economic function, aiming to seek the configuration path that promotes their overall development. By setting the consistency threshold at 0.9 and the frequency threshold at 1, eight configuration paths were finally obtained, which were summarized into four categories, as shown in Table 6. From the output results of the intermediate solution, it can be seen that the consistency of the overall solution is 0.911, surpassing the generally accepted standard of 0.75, which demonstrates the considerable explanatory power of these configurations. The coverage of the total solution is 0.606, indicating that 60.6% of the sample cases can be explained by these eight configurations.

Table 6.

The configuration results of rural households achieving common prosperity.

4.3. Reliance on the New Rural Collective Economic Function Variables to Drive Common Prosperity

The analysis results of the FsQCA3.0 software are shown in Table 6. There are four configurations (CR1, CR2, CR3, CR4) that drive common prosperity through the functional variables of the new rural collective economy. The consistency values of each configuration are 0.941, 0.904, 0.952, and 0.956, respectively. This indicates that these four configurations constitute sufficient conditions for promoting common prosperity. At the same time, the coverage of each configuration is 0.226, 0.27, 0.165, and 0.201, respectively. This reveals that each one has a certain explanatory power to promote common prosperity. Among these, configuration C1 has the largest coverage, making it the main path for the new rural collective economy to foster common prosperity.

- The configuration path of economic function driving common prosperity (CR1). The configuration CR1 indicates that economic function is the core driving condition for the rural collective economy in fostering high-level common prosperity among rural farmers. In configuration CR1, regardless of whether farmers have financial capital or not, even if rural households include non-high-level human capital and non-high-level material capital in the core conditions, as long as the village collective economic organization has high economic function in the core conditions, high social function, high management ability, and high cultural function in the marginal conditions, and rural households have high natural capital and high social capital in the marginal conditions, it can still promote farmers to achieve common prosperity. This configuration reflects that while the economic function of the new rural collective economy is developing at a high level, its strong social functions, management functions, and cultural functions can also drive the improved development of village collectives and the sound development of the natural capital of farmers. Under the condition that the new rural collective economy has a strong economic function, it can improve agricultural efficiency and output, increase agricultural productivity, and optimize the income structure of farmers by integrating farmers’ natural capital and social capital and making effective use of natural resources. At the same time, social capital, including community networks and relationships, promotes knowledge exchange, mutual support, and access to markets, enhancing their competitiveness, while collective organizations provide support through technology, market access, and financial services. They create synergies to achieve sustainable development, raise income levels, strengthen resilience to economic and environmental risks, and promote shared prosperity for the farming communities.

- The configuration path of the collective economy linking high-level livelihood capital for households to achieve common prosperity (CR2). The configuration CR2 shows that the economic function of the rural collective economy matches high-level livelihood capital, which is the core driving condition for farmers to achieve high-level common prosperity. In configuration CR2, regardless of whether farmers have natural capital or not, even if the village collective includes non-high-level cultural functions in the marginal conditions, and rural households include non-high-level social capital in the marginal conditions, as long as the village collective economic organization has high economic functions in the core conditions, high social functions and high management capabilities in the marginal conditions, and rural households have a high level of human capital and material capital in the core conditions and a high level of financial capital in the marginal conditions, it can also promote rural households to achieve common prosperity. This configuration reflects that while the economic function of the new rural collective economy is developing at a high level, farmers with strong human capital, material capital, and financial capital can effectively use existing capital to improve their productivity and innovation ability. This does not only enhance the ability of farmers to participate in the market but also increases farmers’ income and improves their quality of life by improving product quality and production efficiency. In addition, strong human capital and material capital provide farmers with more opportunities to adapt to economic changes and withstand economic risks, playing a key role in promoting rural economic diversification and overall social well-being.

- The configuration path of social function and management function driving common prosperity (CR3, CR4). The configuration of CR3 and CR4 demonstrates that social and management functions are the core driving conditions for the rural collective economy to help farmers to attain high-level common prosperity. In configuration CR3, as long as the new rural collective economy has high social function and high management function in the core conditions, and rural households have a high level of human capital and social capital in the marginal conditions, even if the new rural collective economy includes non-high economic function and non-high cultural function in the marginal conditions, and rural households include a non-high level of physical capital and non-high level of natural capital in the core conditions and non-high levels of financial capital in the marginal conditions, it can also promote farmers to achieve common prosperity. In configuration CR4, as long as the new rural collective economy has high-level social functions and high-level management functions in the core conditions, high-level economic functions and high-level cultural functions in the marginal conditions, and rural households have high-level financial capital in the marginal conditions, even if the core conditions of rural households include non-high-level physical capital and non-high-level natural capital, marginal conditions include non-high-level human capital and non-high-level social capital, it still can help farmers achieve common prosperity.

The social security function of the new rural collective economy aims to provide rural community members with a series of social welfare measures and services by organizing and mobilizing collective resources, so as to ensure their basic living needs, reduce the burden brought by various social risks, enhance the sense of social security of farmers, and promote the economic and social development of rural areas. It is the basic pillar of the village collective social security network and acts as a bridge between farmers and the broader social security system. With the reform and development of the new rural collective economy, the economic attributes of village collective property rights have also begun to strengthen, and rural labor forces have been transferred to more efficient sectors, thus increasing the income of rural households [53]. This income boost effect does not only improve the economic level of farmers, but also strengthens their market participation ability and economic autonomy. With rising income, farmers are better able to invest in their own and their families’ futures, including investments in education, health, and productivity, further boosting economic and social well-being. These dual functions of rural collective economic organizations complement each other. By playing a dual role in economic construction and social security, it does not only improve the economic income of farmers but also enhances their ability to cope with risks and uncertainties, laying a solid foundation for their long-term well-being and development. By ensuring basic social security and actively promoting economic income growth, it effectively promotes the common prosperity of farmers.

4.4. Prosperity Reliance on the Household Livelihood Capital Variables to Drive Common Prosperity

According to the results in Table 6, there are four configurations (CR5, CR6, CR7, CR8) to drive common prosperity by relying on the variables of household livelihood capital, and the consistency of each configuration are 0.95, 0.969, 0.962, and 0.938, respectively. This indicates that these four configurations constitute sufficient conditions for promoting common prosperity. At the same time, the coverage are 0.242, 0.232, 0.178, and 0.187, respectively, indicating that each one has a certain explanatory power to promote common prosperity. The coverage of CR5 is the largest, which is the main way for the farmers’ livelihood capital to drive common prosperity.

- The configuration paths of natural capital driving common prosperity (CR5, CR6 and CR7). The configurations CR5, CR6, and CR7 reveal that high-level natural capital is the core driving condition for farmers in achieving common prosperity. These paths include CR5, CR6, and CR7. In configuration CR5, regardless of whether farmers have social capital, even if the four functions of the new rural collective economy are lacking, as long as farmers have high natural capital in the core conditions, and high human capital, high material capital, and high financial capital in the marginal conditions, it can still promote farmers to achieve common prosperity. In configuration CR6, regardless of whether farmers have financial capital, even if the four functions of the new rural collective economy are lacking, as long as farmers have high natural capital in the core conditions and high human capital, high material capital, and high social capital in the marginal conditions, it can help farmers to achieve common prosperity. In configuration CR7, as long as farmers have high natural capital in the core conditions, it can promote farmers to achieve common prosperity even if the farmers’ other livelihood capital and new rural collective economic functions are deficient. These three configurations reflect that when the economic function of the new rural collective economy is seriously missing, farmers can improve their living standards through traditional livelihoods by relying on high natural capital, so as to achieve common prosperity. In situations where rural collective economic organizations are underdeveloped, but farmers have strong natural capital, the effective use of these forms of natural capital is crucial to promote shared prosperity, and maximizing the economic potential of natural assets can lay the foundation for a more prosperous and resilient rural economy.

High natural capital provides farmers with basic means of production and ecological services, especially for those pure agricultural farmers who mainly rely on agricultural income. More natural capital does not only bring them higher economic income but also enhances their subjective sense of well-being [54]. As the cornerstone of agricultural production systems, natural capital includes natural resources that provide various goods and services for human well-being, ecosystems, and ecological processes. In order to give full play to the advantages of rural natural resources and ecological conditions, the government should seize the development of key industries, promote the ecological development of traditional industries, focus on industrial development strategies based on the local actual situation, build infrastructure networks actively, and adopt the development strategy of adapting to local conditions. The development of green ecological agriculture featuring leisure agriculture and rural homestaying drives the diversification of the rural economy and helps the villagers to deeply realize that “the lifeblood of humanity lies in mountains, waters, forests, fields, lakes, grasslands and deserts” and that “clear waters and green mountains are invaluable assets”, which makes them more motivated on the road to a well-off life [55]. This also narrows the linkage effect gap between cities, promotes industrial transformation and upgrading, and creates new driving forces for the interconnected development of urban agglomeration [56].

- 2.

- The configuration path of human capital and social capital driving common prosperity (CR8). Configuration CR8 indicates that high-level human and social capital are the core conditions for farmers to reach common prosperity. When economic and cultural functions of the new rural collective are seriously missing, farmers have high human capital and high social capital, which can also promote the farmers to achieve common prosperity. Through the introduction of social capital, farmers have a redistribution effect on the allocation of other social resources. Specifically, they make investment decisions through the characteristics of social capital, such as trust, risk sharing, and norms, and indirectly affect the allocation of household resources through its informality [57]. Strong social support networks and professional status can enhance the possibility of resource sharing and information exchange, provide additional support and assistance in the face of economic or other challenges, and help to provide more development opportunities, social support, and access to resources. At the same time, Sun [58] found that the richer the social capital, the stronger the willingness of farmers to participate in the improvement of the rural living environment, and the support and resources provided by social capital can help individuals overcome challenges and obstacles, thus encouraging them to pursue their goals more actively.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

From the micro-perspective of farmers in Zhejiang Province, this article designs four functional condition variables of the new rural collective economy, including economic function, management function, social function, and cultural function. In addition, it designs five livelihood capital condition variables, including material capital, human capital, financial capital, social capital, and natural capital. The fsQCA method is used to investigate how the new rural collective economic function factors and the farmers’ livelihood capital factors achieve interactive matching to promote the common prosperity of farmers.

Our results indicate that the economic, management, social, and cultural functions of the new rural collective economy, as well as the livelihood capital of farmers, are not the necessary conditions for high-level common prosperity of the farmers. Instead, the functions of the new rural collective economy and the livelihood capital of farmers depend on each other, and the linkage matches the production of high-level common prosperity for the farmers. The adequacy results indicate that there are eight configurations of high-level common prosperity for producing farmers, with an overall consistency of 0.911 and an overall coverage of 0.606. We can summarize it into five driving paths: the economic function-driven model of the new rural collective economy, the driven model of the high-level livelihoods’ combined economic functions, the joint model of social function and management functions, the natural capital driven model, and the joint model of human capital and social capital.

5.2. Policy Implications

This article puts forward the following policy recommendations. Firstly, it advocates for the establishment of industrial pillars to enhance the economic functions of the new rural collective economy and promote the material prosperity of rural households. It is suggested that local governments are encouraged to support the development of resources aimed at extending the industrial chain and developing characteristic industries. This entails optimizing the allocation of collective economic resources, promoting effective docking with agricultural business entities, ensuring that the front, middle, and back links of the industrial chain are closely linked, building a complete industrial chain, and achieving stable development. Secondly, local governments are encouraged to strengthen public management services, aimed at improving the management function of the new rural collective economy and promoting the sustainable prosperity of rural households. The new rural collective economy should focus on providing high-quality non-basic public and living services for its members [59], such as improving the daily maintenance of rural sanitary toilets, public culture, and fitness facilities, promoting the operation of garbage classification volunteer services, and providing free health examination services for disadvantaged families and the elderly people. Thirdly, through expanding the scope of social services, the rural collective economy is suggested to give full play to the social functions of the new rural collective economy and promote rural households’ social security; for example, further strengthen the role of the new rural collective economy in rural left-behind elderly care services, provide skills training support for home care, and support families to transform their aging home environment. Finally, government departments should build a coordination mechanism between a new type of rural collective economy and farmers’ livelihood capital, in order to leverage a linkage role in promoting the common prosperity of farmers. By optimizing the allocation of internal production resources, improving the property rights mechanism and the benefit distribution mechanism, it can strengthen the role of the new rural collective economy in integrating farmers into the high-quality development of characteristic agriculture, and in increasing income through dividends as well as employment.

Meanwhile, there are also some research limitations in this article. Firstly, from the factors that affect the common prosperity of farmers, the natural environment is an important limiting factor that leads to insufficient income and poverty for farmers. However, this article did not consider the impact of natural environmental factors. Secondly, when examining household livelihood capital, the measurement of household material capital could not be precise enough. For example, which important agricultural machinery should be included in material capital measurement should be judged based on the current production and operation status of farmers. Thirdly, we only used cross-sectional data, and in the future, we should increase research on time series case data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y. and Z.H.; methodology, S.Y.; software, S.Y.; validation, Y.M.; formal analysis, Y.M.; investigation, S.Y. and Z.H.; resources, M.Z.; data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y. and Z.H.; writing—review and editing, S.Y., Z.H. and M.Z.; visualization, S.Y.; supervision, Z.H.; funding acquisition, M.Z. and Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities of Zhejiang, grant number 2023YW79, the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China, grant number 22YJAZH153, and the Research Project of Soft Science in Zhejiang Province, grant number 2024C35091.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lv, D.; Luo, S. The Policy System and Realization Path to Promote the Common Prosperity of Farmers and Rural Areas. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2022, 44, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- China Daily. Central No. 1 document: For the first time, it is clear what the “new rural collective economy” is and how to do it. China Collect. Econ. 2023, 39, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Q. Several Thoughts on Improving the Stock Rights of Rural Collective Assets: Based on a Survey of Zhejiang Province. Manag. Adm. Rural. Coop. 2023, 5, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K. Research on the Historical Evolution, Key Factors and Internal Mechanism of the Development of New Rural Collective Economy. Master’s Thesis, Yanan University, Yanan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. On China’s Rural Collective Economy in the Past Seventy Years: Achievements and Experience. Stud. Mao Zedong Deng Xiaoping Theor. 2019, 40, 53–60+108–109. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Mu, X. Research on Rural Collective Economic Development and Rural Revitalization in New Era: Theoretical Mechanism, Real Predicament and Achieved Breakthrough. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2020, 11, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S.; Huo, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, F. An Empirical Study of New Rural Collective Economic Organization in Alleviating Relative Poverty among Farmers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Q. A Multi-perspective Analysis on Rural Collective Economic Organization Governs Relative Poverty. Soc. Sci. Front. 2020, 43, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, T.; Dong, X. Village Community Rationality: A New Perspective to Solve the Dilemma of “Three Rural Issues” and “Governance in Three Aspects”. J. CCPS 2010, 14, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L. Realization of Economic and Social Safeguard of Rural Collective under Background of Rural Revitalization-a Case Study on Tongxiang, Zhejiang. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2020, 41, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, C.; Wang, J. The Path Innovation of Participation in Public Goods Supply by Rural Collective Economic Organizations: A Case Study of “Purchasing Reform” in Daning County. Chin. Rural Econ. 2020, 36, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, X. Organization Isomorphism and Governance Embeddedness: How Rural Collective Economy Promotes the High Efficiency of Rural Governance—A Case Study of 13 Towns in Pengzhou City, Sichuan Province. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 43, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, T. Innovation of New Collective Economy and Rural Social Governance in Undeveloped Areas—Through the Comparison between Wang Jiabian and Tangyue. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 20, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, W. Analysis on Innovation of New Rural Collective Rconomic System. Soc. Sci. Guangxi 2009, 25, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, K.; He, A.; Gao, M. Perspective on the “New” of the New Rural Collective Economy. Rural. Manag. 2022, 1, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Cooperative Economy, Collective Economy, New Collective Economy: Comparison and Optimization. Econ. Rev. J. 2021, 36, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee and State Council. Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Steadily Advancing the Reform of the Rural Collective Property Rights System; People Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2017; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, W. Research on the Development of New Rural Collective Economy with Chinese Characteristics of Agricultural Modernization. Seeker 2010, 30, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, W. Historical Evolution of the Concept and Connotation of Common Prosperity. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2022, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Common Prosperity: Concept Discrimination, Centennial Exploration and Modernization Goal. Reform 2021, 34, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, M. Evaluation of Common Prosperity Level and Regional Difference Analysis along the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z. The Source of Common Prosperity Thought and the Path Choice of Farmers’ Rural Realization of Common Prosperity. Econ. Rev. J. 2022, 38, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.; Wu, H.; Peng, Y. Research on the Impact of Rural Labor Mobility on the Common Prosperity of Farmers. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plann. 2023, 44, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Z.; Zeng, Y. Developing New Rural Collective Economy: Realistic Dilemma and Possible Path. J. Harbin Inst. Tech. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 24, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. Building the Theory of Collective Action of Rural Communities with Strong Endogenous Development Ability—Based on the Collective Accumulation and Coordination Mechanism of Developed Village and Hollow Village Communities. Stud. Marx. 2017, 35, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Research on the Development of New Rural Collective Economy from the Perspective of Common Prosperity. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi University of Finance & Economics, Taiyuan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Yang, Y. Can the Reform of Rural Collective Property Rights System Promote the Development of Rural Collective Economy? An Empirical Test Based on the Survey Data of China’s Rural Revitalization. Chin. Rural Econ. 2022, 38, 84–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L. The Development of New Rural Collective Economy and Reorgnization of Rural Society—Based on a Case of Tangyue Village in Guizhou. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2021, 43, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; Lan, H. Why Do Chinese Enterprises Completely Acquire Foreign High-Tech Enterprises—A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis(fsQCA) Based on 94 Cases. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 37, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rangin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Jia, L. Configurational Perspective and Qualitative Comparative Analysis: The New Way of Management Research. J. Manag. World 2017, 33, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, S.; Huang, Y.; Long, W. The Influencing Factors and Realization Path of the Development of New Rural Collective Economy in the Underdeveloped Areas of Western China: An Analysis Based on fsQCA Method. J. Yunnan Agric. Uni. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 17, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Qu, B. Analysis on the Influencing Factors of Village-level Collective Economy Development Based on Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) Method. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plann. 2018, 39, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, F. Read Common Prosperity; Citic Press: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, J. Holding High the Great Banner of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics and Striving Together to Build a Modern Socialist Country in an All-Round Way—Report at the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China; People Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Qian, T.; Huang, X. The Connotation, Realization Path and Measurement Method of Common Prosperity for All. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Measurement of Common Prosperity of Chinese Rural Households Using Graded Response Models: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Construction and Empirical Research of Evaluation Index System of Common Prosperity. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University of Finance and Economics, Lanzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, L. Can the Chinese Farmers’ Specialized Cooperatives Realize the Union of the Weak?—Comparative Analysis Based on Chinese and Japanese Practices. Chin. Rural Econ. 2016, 32, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F.; Liao, X. Functional Study of Rural Collective Economy. Seeker 2010, 30, 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Functional Analysis of Rural Collective Economic Organization. Rural. Manag. 2022, 7, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, X. Analysis of the Economic, Social and Ecological Functions of the Rural Collective Economic Organizations. China Townsh. Enterp. Account. 2008, 16, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, F.; Jin, J.; He, R.; Ning, J.; Wan, X. Farmers’ Livelihood Risks, Livelihood Assets and Adaptation Strategies in Rugao City, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z. Research on Changes of Livelihood Capabilities of Rural Households Encountered by Land Acquisition: Based on Improvement of Sustainable Livelihood Approach. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Luo, C. The Rural Left-Behind Women’s Livelihoods Strategy under the Pressure of Price Rising: Livelihood Diversification. China Rural Surv. 2014, 35, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Poor Mountain Farmers Livelihood Capital Impact on Livelihoods Strategy Research: Based on the Survey Data Pingwu and Nanjiang County of Sichuan Province. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Liu, H.; Zhao, B. The Practice and Countermeasures of Increasing the Reform of Farmers’ Property Income in Sichuan Province. Rural Econ. 2016, 34, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Jin, H. The Changes of Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies and the Influencing Factors from the Perspective of the Livelihood Capital: Based on the four periods of the CFPS Tracking Data. Res. Agric. Mod. 2021, 42, 941–952. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Research on the Impact of Digital Financial Development on Rural Household Livelihood. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss, P.C. Building Better Causal Theories: A fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C.; Fiss, P.C. Net Effects Analysis Versus Configurational Analysis: An Empirical Demonstration; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, L. Rural Land Right Verification, “Separation of Ownership Rights” and Revenue-Increasing Effect—Based on the Dual Perspectives of Collective and Peasant Households. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 46, 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Ma, L.; Zong, Y. Research on Differences in Farmers’ Well-being and Enhancement Paths from Subjective and Objective Perspective. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 42, 39–52+134. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Lv, L. Research on the Path of Rural Ecological Civilization Construction under the Concept of Life Community. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Zheng, Y. Study on the Linkage Effect Measurement and Driving Force of Beibu Gulf Urban Agglomeration Based on Green innovation System. Resour. Dev. Market. 2024. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. Mechanism of Social Capital Affect Income: From the Perspective of Resource Allocation Function of Social Capital. Econ. Probl. 2017, 39, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q. Study on the Influencing Factors of the Willingness of Tibetan Peasant Households to Participate in the Improvement of Rural Living Environment. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2019, 35, 976–985. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Qi, X. Research on the Historical Evolution and Development Direction of the Public Service Function Undertaken by Rural Collective Economic Organizations. J. Shihezi Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 37, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).