Abstract

With the frequent occurrence of online public opinion events, the problem of product stigma is becoming increasingly serious. Enterprises must use effective quality information disclosure strategies to reduce losses affecting market sales and profit. Therefore, this paper aims to address the supply chain structure composed of one product manufacturer and one component manufacturer under the influence of stigma. It constructs a decision optimization model under three scenarios: no information disclosure, the product manufacturer disclosures information, and the component manufacturer disclosures information, and uses Stackelberg game theory to solve and analyze the model. Furthermore, we use numerical examples to verify the model results, and provide management suggestions for enterprises. The research results show that enterprises suffering from product stigma should actively implement information disclosure strategies to reduce their profit losses, and the lower the stigma level, the better the effect of information disclosure will be; when the stigma level becomes more serious, enterprises should take timely steps to reduce the sales price of products, the sales price of components, and the efforts to disclose information; for industries that value confidentiality of product information, although the implementation of information disclosure by the component manufacturer can require less effort for information disclosure, the two enterprises will suffer higher economic losses.

1. Introduction

The problem of product stigma has existed for decades, but in recent years, with the acceleration of information transmission via online social media, the problem of product stigma has become increasingly serious [1] (Ritvala et al., 2021). In August 2020, a Tesla Model 3 in Wenzhou, China, suffered a serious accident on the highway after suspected brake failure, which triggered a wave of doubts on the Internet about the quality of new energy vehicles. Even though the incident was clarified in 2022 as a driver’s mistake, the stigma relating to the quality of new energy vehicles has had a serious adverse impact on market development in the past two years. After that, although Tesla implemented a series of disclosure measures to provide evidence of the quality of its vehicles to consumers, the effect was generally subpar. The stigma surrounding product quality has become a major problem for Tesla. In fact, in recent years, new energy vehicles (NEVs) have been continuously stigmatized in China. People have learned through social media about occasional accidents such as brake failure, steering loss, and spontaneous combustion of NEVs, causing panic and attributing these to serious quality problems that may be common among all NEV products. According to statistics, in the top 100 list of public opinion risk events in China in the first half of 2023, 13 references to new energy vehicles were listed.

The range of products that have been stigmatized is very broad; in addition to new energy vehicles, food additives, health care drugs, and carbonated drinks in different countries are also in the areas hit hard by stigma [2]. For example, in the healthcare products industry, health supplements produced by Japan’s Kobayashi Pharmaceutical that contain red koji have been widely discussed due to causing health damage to consumers. According to data from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, as of 27 May 2024, there have been 5 deaths and over 280 hospitalizations among consumers who had taken Kobayashi Pharmaceutical’s health supplements containing red koji. This incident sparked public concerns about the safety of health supplements and has had a significant negative impact on both upstream and downstream enterprises in the supply chain, as well as the entire health supplements industry, leading to a short-term decline in industry confidence and a sharp drop in sales. In summary, the problem of product stigmatization not only seriously affects the harmony of trade relations but also has great impact on consumer markets and the future development of industries and is not conducive to the stability of industries and supply chains. Only through understanding the causes of stigmatization can we better propose countermeasures for governance.

Stigma comes from information asymmetry, which means that the quality information of products that consumers know is far from the actual quality information of those products [3]. Therefore, in order to solve the problem of information asymmetry, it is imperative to implement timely and accurate quality information disclosure strategies [4]. Information disclosure refers to the fact that consumers’ lack of understanding of product quality leads to a reduction in demand, so enterprises can take various steps to improve consumers’ understanding of product quality, such as organizing factory visits, free trials, or an advertising push [5]. In fact, information disclosure has been adopted by many enterprises in practice. Tesla has established an information sharing system with supply chain partners such as CATL, Panasonic, and LG, and uses EDR query software to disclose vehicle dynamic and safety systems data to consumers. However, some enterprises are concerned about losing information advantages due to data leakage, and meanwhile, high-quality information disclosure can result in high disclosure costs. Therefore, they would rather bear the loss caused by stigma than disclose quality information. So, how does the stigma of product quality affect enterprise decisions and profits? Is there any difference in the impact of stigma level on different enterprises in the supply chain? What efforts relating to information disclosure should enterprises make to disclose quality information to consumers? How do these affect enterprises’ pricing decisions and profits? These are important issues that need to be addressed.

Compared with previous studies, the theoretical contributions of this study are mainly in the following areas. Firstly, in the previous research on product quality stigma, scholars mainly pointed out the adverse impact of stigma on corporate profits based on theory and case analysis and described the strategies that enterprises can take in the face of stigma, such as prevention and identification. However, there have been no studies like this one, which presents a mathematical model of stigma and explores the different impacts of different stigma levels on corporate decisions and profits through mathematical modeling, as well as the decision-adjustment methods that enterprises should adopt. Secondly, in the previous research on stigma, there was no different management advice for different enterprises regarding their coping strategies. However, in practice, stigma is bound to have different impacts on enterprises with different market distances, such as product manufacturers and component manufacturers in the supply chain. Therefore, it is necessary to study the impact of stigma level on different enterprises. Finally, in the field of information disclosure research, no scholars have yet used a mathematical model to describe the relationship between stigma level and information disclosure efforts based on their characteristics and in-depth exploration of their relationship and impact on enterprises. This study also makes an important theoretical contribution through accurately modeling the relationship between stigma level and information disclosure.

This paper contributes to business operations in three ways. First, it provides guidance for corporations to develop information disclosure strategies. Corporations can choose appropriate subjects for information disclosure, timing, and intensity based on the degree of stigma of their products, industry characteristics, and the market need to minimize profit losses. Second, the conclusions of this paper can serve as a reference for corporations’ supply chain management. Through understanding the impact of different information disclosure strategies on corporate decision making and profits, corporations can flexibly adjust their supply chain optimization plans, optimize resource allocation, and improve the efficiency and stability of the supply chain. Third, the research conclusions can enhance corporations’ market competitiveness. Through actively implementing information disclosure strategies, corporations can enhance their brand image and reputation, increase consumer trust, and thereby enhance their market competitiveness.

The contributions of this study to social development include the following three aspects. First, the research conclusions can promote market information transparency and protect consumer rights. The research conclusions emphasize the role of information disclosure in reducing the market damage caused by stigmatization, which helps enhance the transparency of product quality information and protect consumer rights, promoting social fairness and justice. Second, the conclusions can guide the healthy development of the industry. For industries that place particular emphasis on the confidentiality of product information, this study provides strategies for reducing economic profit losses while protecting information. This helps guide the industry to find a balance between protecting intellectual property and consumer rights, promoting its healthy development. Third, this study can enhance public confidence in product quality and safety. Through revealing the role of information disclosure in reducing product stigmatization, this study helps enhance public confidence in product quality and safety, improving consumer satisfaction and loyalty. This is of great significance for maintaining social stability and promoting sustainable economic development.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant research progress and analyzes the research gap addressed in this paper. Section 3 describes the problem and model assumptions and explains the notations used in the model. Section 4 constructs and solves the model under three scenarios: no information disclosure, the product manufacturer disclosures information, and the component manufacturer disclosures information, and preliminarily analyzes the model results. Section 5 uses case analysis to verify the model results and provides management insights for optimizing operational decisions. Section 6 summarizes the full paper and proposes extensions that scholars can address in the future.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Definition and Formation of Stigma

Stigma was first proposed by Erving Goffman in 1963, referring to the derogatory and insulting label given to an individual or group due to their characteristics such as disease, defect, or race, leading to a lower social status. In the continuous development of the concept of stigma, scholars have gradually extended it from the individual level to the organizational level [6,7,8]. Among them, the most widely accepted viewpoint is that of [8], who defined organizational stigma as “a label that can make stakeholders realize the existence of essential and deep defects in an organization, thereby making it depersonalized and losing trust”. As a negative social evaluation of an organization, the formation of stigma is not only based on the misconduct of individuals in the organization but is also inseparable from fundamental violation of the organization’s overall belief system, ideology, and values widely recognized by the public and may eventually cause different degrees of disorder and destruction [9]. This kind of destruction is not only targeted at a certain part of the organization but is also completely depersonalized and causes systematic economic or social sanctions [10]. The subject of sanctions is no longer just the public but has evolved into the stakeholder groups of the organization [11]. Stigma is usually scaled, which means that at the beginning, only a few individuals make negative evaluations of the organization but when the scale of the social audience’s negative evaluation reaches a critical point, stigma gradually forms [12].

2.2. Stigma of Product Quality

Among of the important factors that lead to corporate stigma, quality issues are no longer limited to the marketing aspect of the product itself but also represent corporate social responsibility. Once the behavior of the enterprise deviates from the expected quality standards, it may suffer due to criticism from consumers, media, and government departments, which not only damages the reputation of the enterprise for the continued operation of the product but also brings serious quality stigma to the enterprise’s entire organization or even the industry. The quality issues that may lead to stigma are multi-dimensional [13]. Some scholars have divided the dimensions of consumer-perceived quality into service, safety, reliability, lifespan, and appearance [14]. Some scholars have also conducted research based on the way consumers perceive product quality, pointing out that factors such as adverse environment [15], visual characteristics [16], and evaluator status [17] can have a negative impact on perceived quality, resulting in stigma [18]. The main limitation of the above studies is that they focus only on the causes, dimensions, and perception methods of stigma from the perspective of quality, and none of them proposes how to alleviate the practical problems of quality-based stigma through decision optimization.

2.3. Information Disclosure

As the end participants of the supply chain structure, consumers always pay high attention to product performance, market, and quality information, especially the acquisition of actual product quality information, which is the core factor affecting consumers’ purchasing decisions [19,20,21]. However, the asymmetry of quality information acquisition [22] can easily lead to consumers inadequately understanding the actual quality of products. To this end, enterprises can disclose the actual quality information of products to consumers through advertising, trial use, and sample delivery. The subject, the applicable conditions, and the impact on enterprises’ decision making in relation to quality information disclosure have also become the focus of academic attention in recent years [23]. As the producers of products, manufacturers usually have a better understanding of the actual quality status of products and consumers’ quality preferences than retailers [24], so manufacturers are usually the subjects of quality information disclosure. Before information disclosure, manufacturers first need to determine the feasibility and necessity of quality information disclosure [25], including the trade-off between information disclosure benefits and high-level disclosure costs based on customer attention and search costs [26], as well as the negative impact on market and supply chain competition that may be brought about via releasing actual quality information to customers [27]. The impact on the supply chain is mainly based on the “free rider” effect caused by quality information disclosure. Under the disclosure of quality information from manufacturers, although retailers and other supply chain enterprises also benefit from the improvement in consumers’ perceptions of product quality, adjustments to price and other decisions may also damage manufacturers’ benefits, thus negatively affecting manufacturers’ disclosure willingness and efforts. In this context, choosing not to disclose quality information may help manufacturers obtain higher benefits.

2.4. Supply Chain Management

The repeated controversies over supply chain-related events indicate that it is necessary to develop theoretical research on supply chain management to address challenges in practice [28]. Currently, the research field of supply chain management includes ecological social systems, corporate social responsibility, and enterprise economics. Among these, the dynamic capabilities of supply chain management in the enterprise economy [29] and the business environment, along with social factors [30], have been proven to be very important for enterprises’ supply chain management practices. In addition, some scholars have studied the role of supply chain collaboration in new product development processes, providing important theoretical support for researchers and management decision makers [31]; others have studied the important impact of sustainable supply chain management on the environment, society, and corporate responsibility, affirming the important role of supply management in improving organizational competitiveness [32]. All of these studies have certain reference value for enterprise supply chain management practices, but none of them have expanded the research to address the level of stigma that has become increasingly severe in recent years.

2.5. Research Gap

The above literature mainly focuses on the development of enterprises in the supply chain and the strategies for dealing with product quality stigma. However, how to optimize decision making from the perspective of the supply chain in response to product quality stigma has not been studied. Specifically, previous studies on product quality stigma have revealed that consumers’ distrust of product quality leads to significant economic losses for enterprises, so enterprises need to take timely measures such as prevention and identification. However, scholars have not considered the impact of stigma on enterprises’ decision making from the perspective of the supply chain. In the field of information disclosure, scholars have emphasized that information asymmetry is an important reason for the reduction of supply chain operation efficiency and pointed out that enterprises should actively disclose information such as demand, inventory, cost, process, and performance. However, no scholar has been able to use mathematical models to accurately describe the impact of stigma level and disclosure of information about quality on enterprises’ decision making and profit under conditions of stigma. Therefore, in summary, this paper studies the decision-making problem relating to disclosure of supply chain quality information under the influence of stigma and provides theoretical and practical guidance for the operation and management of supply chain enterprises.

3. Problem Description and Model Assumptions

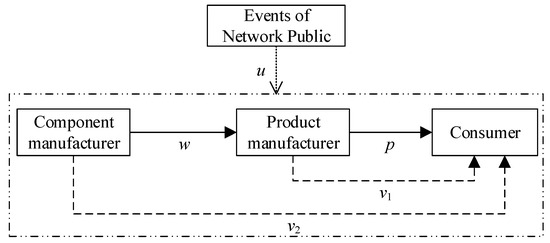

As shown in Figure 1, the supply chain structure studied in this paper includes a product manufacturer and a component manufacturer. Firstly, the component manufacturer produces components with a quality level of q and a unit cost of c2, and sells the components to the product manufacturer at a price of w. After obtaining the components, the product manufacturer produces the product at a unit cost of c1, and sells the product to consumers at a price of p. During the product sales process, the frequent occurrence of online public opinion events leads to the stigma of the product, with a stigma level of u. As the stigma leads to defects in consumers’ perception of the quality of the product’s components, the product manufacturer or component manufacturer can take v information disclosure efforts to disclose the actual quality of the product to consumers. To describe this from the perspective of specific industries, as a typical example, the component manufacturer represents a battery manufacturer in the new energy vehicle industry, and the product manufacturer represents a new energy vehicle manufacturer.

Figure 1.

Supply chain structure studied in this paper.

In order to more accurately describe the decision-making problem relating to disclosure of information about qulaity under the influence of stigma, we put forward the following assumptions:

Assumption 1:

In the game with the product manufacturer, the component manufacturer occupies a dominant position.This is because in the process of product production, the scarcity of technology leads to a small number of key component manufacturers, and the large number of product manufacturers leads to the fact that component manufacturers have absolute discourse power in the process of selecting product manufacturers as partners. Therefore, this paper assumes that the component manufacturer occupies a dominant position in the game with the product manufacturer, and product manufacturer is the follower in the game.

Assumption 2:

In the game between the product manufacturer and component manufacturer, both enterprises optimize decisions such as price and information disclosure efforts with the goal of maximizing their own economic profits. That is, the model constructed in this paper does not consider other irrational behaviors of enterprises, such as fairness concerns.

Assumption 3:

In the operational practice of enterprises, in addition to stigma relating to the quality of key components of products, there may be stigmas regarding service quality and R&D quality. For the sake of simplification of the study, the stigma considered in this paper refers to product quality, without considering other types of stigma.

Assumption 4:

We assume that the impact of product sales price and product quality on demand is linear. That is, when there is no stigma, product demand can be expressed as Q = a − bp + mq, where m is the sensitivity coefficient of product quality to demand. Since “refuting rumors is more difficult than spreading rumors”, that is, compared with information disclosure effort v, the negative impact of stigma level u is exponentially greater. Therefore, when there is stigma, product demand can be expressed as Q = a − bp + (m − u2) q. When enterprises attempt to adopt information disclosure strategies, it can be assumed that the product sales volume is Q = a − bp + (m − u2 + v) e.

Assumption 5:

Similar to the research by Wang et al. (2022) [24], it is assumed that the effort cost of quality information disclosure is jv2/2, that is, the effort cost increases exponentially with the increase in information disclosure effort v. In addition, to ensure that the model is consistent with the actual situation, it is assumed that m − u2 > 0. This is because once m − u2 ≤ 0 occurs, then product quality q negatively affects sales volume, which is contrary to the actual situation.

For convenience, we summarize the notations used in the paper in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notations used in the models.

4. Model Formulation

In this section, we develop decision models for products with stigma effects in three scenarios: no information disclosure, the product manufacturer disclosures information, and the component manufacturer disclosures information. Employing Stackelberg game theory to solve the model, we analyze the results and provide management recommendations for enterprise operational practices.

We used Stackelberg game theory to solve and analyze the model. The Stackelberg game is used to describe market competition with a leader and a follower relationship. In this game model, there is an assumed leader and a follower, and the leader can predict the follower’s actions, while the follower cannot predict the leader’s actions. The leader can influence the follower’s actions via modifying their strategies to achieve maximum benefit. This process is repeated until a Nash equilibrium is reached.

4.1. No Information Disclosure

Due to high costs of information disclosure and financial pressures faced by enterprises, when product quality is stigmatized, enterprises may choose not to disclose information about quality. Therefore, in this section, we study the product manufacturer and component manufacturer in a supply chain structure with stigmatization problems and explore the decision-optimization model without adopting a quality information disclosure strategy. Specifically, as the dominant player in the game, the component manufacturer first optimizes w. After observing the decision of the component manufacturer, the product manufacturer optimizes p. According to the reverse solving method, the profit function of the product manufacturer is first constructed as follows:

The first and second partial derivatives of π1 with respect to p are:

Since b > 0, the second-order partial derivative of π1 with respect to p is −2b < 0, and π1 is thus concave with respect to p. That is, there exists an optimal p^ that allows π1 to reach its maximum value.

Let ∂π1/∂p = 0 be solved, and the result is as follows:

We construct the profit function of the component manufacturer and substitute p^ into the function, i.e.,:

The first and second partial derivatives of π2 with respect to w are as follows:

Since b > 0, the second partial derivative of π2 with respect to w is less than 0, that is, π2 is an concave function with respect to w, and there exists an optimal w^ that allows π2 to reach its maximum value.

Let ∂π2/∂w = 0 and combine it with (2); the optimal decisions w^ and p^ can be solved as shown in Table 2. Substitute p^ and w^ into (1) and (3), and the optimal profits π1^ and π2^ of the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer can be solved as shown in Table 2, without disclosing quality information.

Table 2.

Optimal decisions and profits under different situations of quality information disclosure.

4.2. The Product Manufacturer Discloses Information

For products that are severely affected by stigma, if the product manufacturer has sufficient funds and is not worried about information disclosure, they can adopt the information disclosure strategy. In this subsection, we construct a decision-making model for the product manufacturer when they disclose information. Similar to Section 4.1, as the dominant player in the game, the component manufacturer first optimizes the component sales price w. After observing the decision of the component manufacturer, the product manufacturer then optimizes the product sales price p and information disclosure effort v1. According to the reverse solving method, we construct the profit function of the product manufacturer as follows:

Proposition 1.

When 4bi − q2 > 0, there exists an optimal p*, v* that maximizes π1 as follows:

The proof of Proposition 1 is shown in the Appendix A.

According to Proposition 1, we can preliminarily obtain the optimal price and the decision of the product manufacturer regarding efforts to disclose information in the case that the product manufacturer adopts information disclosure, as shown in (5) and (6). However, as (5) and (6) still contain the decision variable w of the component manufacturer, they do not express the final decision. Subsequently, we further study the optimal decision of the component manufacturer based on (5) and (6).

Next, we construct the profit function of the component manufacturer and substitute p*, v1* into it, namely:

The first and second partial derivatives of π2 with respect to w are as follows:

Since b > 0, q > 0, i > 0, only by making q2 − 4bi < 0 can the second-order partial derivative of π2 with respect to w be less than 0. At this time, π2 is a concave function with respect to w, that is, there exists an optimal w* that allows π2 to reach its maximum value.

Making ∂π2/∂w = 0 and simultaneously applying it to (4) and (5), the optimal decisions v1*, w*, and p* can be obtained as shown in Table 2. Substituting v1*, w*, and p* into (4) and (7), the optimal profits π1* and π2* of the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer can be obtained as shown in Table 2.

4.3. The Product Component Disclosures Information

As an important enterprise in the supply chain, the component manufacturer also has actual information about product quality, so they may also be responsible for the disclosure of information about quality to consumers. When the component manufacturer discloses information, as the dominant player in the game, the component manufacturer first optimizes the sales price w and the information disclosure effort v2. The product manufacturer optimizes the product sales price p after observing the decision of the component manufacturer. According to the reverse solving method, we first construct the profit function of the product manufacturer as follows:

The first and second partial derivatives of π1 with respect to p are:

Setting ∂π1/∂p = 0, the optimal p** can be solved as follows:

Constructing the profit function of the component manufacturer and substituting p** into it, we can obtain:

Proposition 2.

When 8bi − q2 > 0, there exists an optimal w**, v** that maximizes π2 as follows:

The proof of Proposition 2 is shown in the Appendix A.

According to Proposition 2, we can obtain the optimal decision for the component manufacturer w**, v2** in the case of information disclosure by the component manufacturer. According to (11) and (12), the component manufacturer has time to adjust the decision relating to component price and information disclosure effort when the stigma level and other factors change, so as to optimize their own profit.

Substitute w**, v2** into (9), and the optimal sales price of the product can be solved as shown in Table 2. Substitute w**, v2** and p** into (8) and (10), and the optimal profits of the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer in the case of the component manufacturer’s information disclosure strategy are shown in Table 2.

Corollary 1.

In the case where the enterprise does not provide quality information disclosure, the stigma level is negatively correlated with the optimal product selling price and the component selling price of the enterprise; in the two cases where the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer provide quality information disclosure, the stigma level is negatively correlated with the optimal product selling price, the component selling price, and the quality information disclosure effort.

The proof of Corollary 1 is shown in the Appendix A.

Corollary 1 provides guidance for how enterprises should adjust their decisions when the stigma level changes. According to Corollary 1, when the product stigma level in the market is more serious, regardless of whether or not the enterprise conducts information disclosure and regardless of which enterprise implements information disclosure, the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer should reduce their profit losses via lowering prices. According to cognition in operational practice, it is reasonable to reduce prices to deal with more serious stigma levels. However, Corollary 1 also shows that when the stigma level increases, the enterprise should not choose to improve but should reduce their information disclosure effort, which is obviously an interesting finding.

Corollary 2.

In the cases where the enterprise does not provide quality information disclosure and the product manufacturer provides quality information disclosure, the stigma level has a negative correlation with the profits of the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer. In the case where the component manufacturer provides quality information disclosure, the stigma level has a negative correlation with the profits of the product manufacturer.

The proof of Corollary 2 is shown in the Appendix A.

Corollary 2 indicates the impact of the change in stigma level on the profits of the enterprise. That is, in the above cases, when the stigma level increases, the profits of both the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer decrease. This corollary is also in line with operational practice. However, through the analysis of this equation, we cannot directly reveal the trend of the change in the profits of the component manufacturer when the component manufacturer discloses information about quality. Therefore, it is tested further in the example calculation analysis in Chapter 5.

Corollary 3.

At the same level of stigma, compared with the product manufacturer, quality information disclosure by the component manufacturer requires less disclosure effort, i.e., v1* > v2**.

The proof of Corollary 3 is provided in the Appendix A.

Although information disclosure is beneficial for enterprises to deal with stigma, information about product quality includes confidential information relating to manufacturing, testing, measurement, transportation, and other aspects of the product, so the higher the disclosure effort is, the greater the risk of exposing corporate trade secrets. Corollary 3 indicates that compared with the product manufacturer, disclosure of quality information by the component manufacturer can require less disclosure effort at the same level of stigma. Therefore, for enterprises with special considerations for product confidentiality, information disclosure by the component manufacturer is a better choice.

Corollary 4.

When 1/16b > i/4(4bi − q2) and 1/16b > 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2, for the product manufacturer, the profit without disclosure of quality information is better than that with disclosure of quality information; when i/4(4bi − q2) > 1/16b and i/4(4bi − q2) > 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2, if the product manufacturer is responsible for disclosure of quality information, then they will obtain higher profits; when 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2 > 1/16b and 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2 > i/4(4bi − q2), if the component manufacturer is responsible for disclosure of quality information, then the product manufacturer obtains higher profits.

The proof of Corollary 4 is shown in the Appendix A.

Corollary 4 indicates that under the influence of stigma, whether to implement information disclosure and who implements information disclosure affect the profit obtained by the product manufacturer. Furthermore, the profit for the product manufacturer in different situations depends on only the actual values of the consumer’s sensitivity coefficient b to price, the product quality q, and the cost coefficient i of information disclosure effort, which are not affected by other factors. Similar to Corollary 2, because the optimal profit equation of the component manufacturer is too complex, we cannot determine the factors that affect the profit of the component manufacturer through directly analyzing the equation. We further study this issue in Section 5.

5. Case Study and Discussion

5.1. Case Study

In the above study, we studied the supply chain decision optimization model under the influence of product quality stigma under three scenarios: no information disclosure, the product manufacturer disclosures information, and the component manufacturer disclosures information. The level of product stigma in the market often fluctuates, so we preliminarily analyzed the impact of changes in stigma level on the decision making and profit of enterprises under the different scenarios. In this section, we use the method of case analysis to further analyze the model results and provide management enlightenment for enterprises.

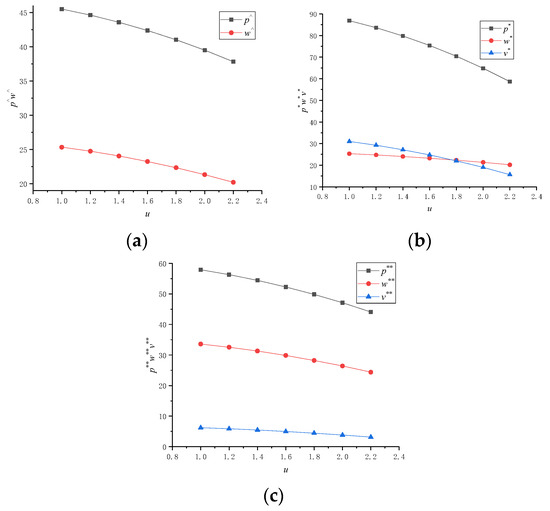

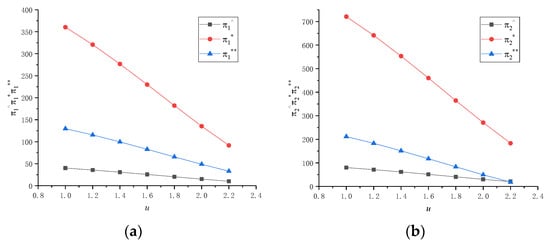

In this section, we assume that the cost to the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer is c1 = c2 = 15, the coefficient of product quality sensitivity to demand is m = 15, the product quality is q = 1, the cost coefficient of information disclosure work is i = 3, the sales volume of the product foundation in the market is a = 20, the coefficient of the impact of retail price on demand is b = 1.5, and that u increases from 1.0 to 2.2 at a rate of 0.2, which means that as the product is sold in the market, the level of stigma of the product starts from 1.0 and increases at a rate of 0.2 to 2.2 over time. We substituted the above values into the research results for the three scenarios in Section 4 and simulated them with Mathematica, and we obtained the data results in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 and further plotted Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Table 3.

Effects of u in the case of no information disclosure.

Table 4.

Effects of u in the case where the product manufacturer discloses information.

Table 5.

Effects of u in the case where the component manufacturer discloses information.

Figure 2.

Effects of u on decision making in three situations: (a) the situation of no information disclosure; (b) the situation of the product manufacturer discloses information; (c) the situation of the component manufacturer discloses information.

Figure 3.

Effects of u on profits in two situations. ((a). the situation of the product manufacturer discloses information; (b). the situation of the component manufacturer discloses information).

Firstly, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, product stigma level has a negative impact on the sales price of products, the sales price of components, and the information disclosure efforts of enterprises, as well as the profits of product manufacturers and component manufacturers. The increase in stigma level exponentially damages consumers’ perception of product quality and significantly reduces product sales. Therefore, in order to minimize their losses, the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer can lower prices to reduce the speed of market sales decline caused by stigma. Interestingly, stigma level also has a negative impact on enterprises’ information disclosure efforts. That is, when the stigma level is low, enterprises can implement high-level information disclosure efforts to minimize the adverse effects of stigma. However, when the stigma level is serious, enterprises should choose to maintain their information disclosure efforts at a lower level. On the one hand, this is because the efficiency of enhancing information disclosure efforts to reduce the adverse effects of stigma is already low at such a time, and on the other hand, this can also reduce the cost of information disclosure.

Secondly, as shown in Table 4 and Table 5, when the component manufacturer compared with the product manufacturer is responsible for information disclosure, the enterprise spends less effort on information disclosure. Product quality information usually contains potentially confidential information about product output, sales volume, transportation volume, and so on. Therefore, the more information an enterprise discloses, the more likely it is for competing enterprises to collect core information, causing serious information security incidents. Therefore, although at the same level of stigma, the profit of enterprises when the component manufacturer implements information disclosure is significantly lower than when the manufacturer does so, lower efforts relating to information disclosure at such times also reduce the potential risk of information leakage. That is to say, when choosing whether to implement information disclosure by the product manufacturer or the component manufacturer, enterprises need to weigh between “disclosure of less information” or “reduction of loss” based on the actual confidentiality level of product information.

Finally, as shown in Figure 3, whether for product manufacturers or component manufacturers, the implementation of information disclosure can help them obtain higher profits, and the effect of information disclosure is most significant when the stigma level is low. This is because although efforts relating to information disclosure incur certain costs, they can also continuously mitigate the adverse effects of stigma, re-boost consumers’ perceptions of product quality in the market, and ultimately reduce losses for product manufacturers and component manufacturers. However, when the stigma level is high, even if the enterprise invests highly in information disclosure, it is difficult to recover market and economic losses due to the fact that “refuting rumors is more difficult than creating rumors”; that is, the improvement of information disclosure efforts is not enough to prevent the damage of stigma. Therefore, compared with situations of high stigma levels, enterprises should actively implement information disclosure when the stigma level is low, to reduce economic losses.

5.2. Results Discussion

This study has some similarities with the existing literature. For example, on the one hand, in order to more accurately assess the impact of information disclosure levels on outcomes, previous studies often used quantitative analysis methods involving building models and collecting data to test hypotheses. Similarly, the mathematical model constructed in this study also uses similar methods to evaluate how information disclosure levels affect the market. On the other hand, these studies all emphasize the importance of information disclosure in shaping and maintaining corporate reputation. When a company faces a reputation crisis due to a quality scandal, the company can better manage its public image and mitigate potential negative impacts through increasing the level of its efforts in information disclosure. This is consistent with previous research on the relationship between information disclosure and corporate reputation.

This study also has some differences from the existing literature. On the one hand, although many studies have explored the issue of stigma, previous studies have mostly focused on brand management and have paid relatively less attention to research specifically focusing on product quality stigma. Therefore, this study has a certain degree of uniqueness in terms of problem selection. On the other hand, this study takes into account some new factors and assumptions when building the model, such as including the level of information disclosure effort as a key variable, which has been less directly considered in previous studies in the context of the non-economic factor of information disclosure and its effects on decision making. Taking the level of information disclosure effort as a key variable highlights the importance of information transparency in corporate strategy and decision making, providing a new perspective for understanding corporate behavior.

The results of this study fit in with existing theory. On the one hand, the research results can deepen our understanding of the theory of asymmetric information, which holds that the information possessed by different parties in the market is asymmetric and may lead to decision-making mistakes and market failure. The introduction of information disclosure efforts in this study is a direct response to the problem of asymmetric information. In the market, information asymmetry may lead to decision-making mistakes by investors, consumers, or other stakeholders, thereby affecting the market performance and long-term development of enterprises. The model further confirms the crucial role of information disclosure in alleviating the problem of asymmetric information, through considering the level of information disclosure efforts. Through applying the model to actual cases, we can further analyze how information disclosure affects the information structure and trading behavior in the market, thereby driving the development and improvement of the theory. On the other hand, the research results are consistent with stakeholder theory. Stakeholder theory holds that enterprises should consider the interests of all stakeholders. The consideration of different stakeholders in the supply chain in this model reflects that when facing reputational damage, enterprises need to consider the reactions and interests of multiple stakeholders, which is consistent with stakeholder theory. When facing the challenge of product quality stigma, companies can jointly address the issue and achieve common development through actively communicating and cooperating with stakeholders.

This study has successfully addressed the following challenges. First, it helps businesses cope with the challenge of product quality stigma. Product quality stigma poses a serious threat to companies’ reputation and market position, potentially leading to a decline in consumer trust, a reduction in market share, and a shake in investor confidence. This study reveals the crucial role of effort level in information disclosure in mitigating the negative effects of stigma. Companies can enhance their information disclosure efforts to send positive signals to the market and stakeholders, rebuild their brand image, and restore market trust. Second, this study can help formulate inter-firm cooperation and competition strategies. When facing the problem of quality stigma, not only do different supply chain enterprises need to pay attention to their own internal decision making, but they also need to consider their cooperation and competition with other enterprises. The research results of this paper provide a basis for enterprises to formulate effective strategies for cooperation and competition. Third, it helps enterprises respond to the challenges of decision optimization. The stigma problem poses huge challenges for enterprises in decision optimization, as enterprises need to balance the risks and benefits of different strategies to find the optimal response. The decision model built in this paper provides decision support for enterprises facing stigma, helping them to more accurately evaluate the effects of different strategies and formulate corresponding countermeasures to reduce potential risks.

The research framework and model results of this paper can also be applied to other fields, such as food additives, carbonated drinks, and healthcare products. When food additives face stigmatization, such as being questioned about safety or potential health risks, manufacturers should respond promptly and disclose relevant information to mitigate the negative impact. Specifically, when stigmatization is light, effective reduction of profit loss can be achieved through timely and accurate information disclosure. When stigmatization intensifies, in addition to increasing the disclosure efforts, lower product prices may also be considered in order to attract consumers and maintain market share. For healthcare products facing stigmatization, such as questioning about their effectiveness or safety concerns, manufacturers should promptly disclose information to clarify the facts and dispel misunderstandings. When stigmatization is light, transparent information disclosure can help maintain brand image and reduce profit loss. For industries that place a high value on product information confidentiality, such as certain patented drugs, partial information disclosure by suppliers of raw materials can be considered to reduce costs, but the balance between information confidentiality and market demand needs to be carefully maintained.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Results

To address the issue of market damage caused by product stigma, this paper constructs and solves a decision model based on Stackelberg game theory for a supply chain structure composed of a product manufacturer and a component manufacturer. Specifically, this paper constructs models under three scenarios: no information disclosure, the product manufacturer disclosures information, and the component manufacturer disclosures information. Furthermore, this paper solves the equations for the optimal decision and profit of each enterprise and makes a preliminary analysis of the model results. Finally, we use case analysis to verify the model results, combined with operational practices to provide management suggestions for enterprises in terms of information disclosure subjects, disclosure timing, and disclosure efforts.

The main management implications obtained from our model analysis are as follows: for related enterprises suffering from product stigma, we suggest that they should actively implement information disclosure strategies to reduce their profit losses, and the lower the stigma level, the better the effect of information disclosure; when the stigma gradually becomes more serious, enterprises should take timely steps to reduce the sales price of products, the sales price of parts and components, and information disclosure efforts, to reduce their losses; for some industries that attach particular importance to the confidentiality of product information, the implementation of information disclosure by the component manufacturer can cost less information disclosure effort, but at the cost that all enterprises will lose more economic profits.

The results of this study can be explained based on previous research. First, for example, previous stigma-related research suggested that consumers’ incorrect assessment of product quality attributes could lead to product-quality-related stigma. Product quality issues represent the company’s responsibility for social issues, and clear information about corporate social responsibility may enable consumers to maintain a positive attitude towards the company and its products. Therefore, when product manufacturers face stigma, they can effectively respond to consumer doubts and concerns through adopting information disclosure strategies related to product quality. Through timely and transparent disclosure of relevant information, companies can demonstrate their efforts and achievements in addressing stigma issues and eliminate consumer doubts and misconceptions. This disclosure of positive information helps to rebuild the company’s image, restore consumer confidence, and ultimately promote sales and market share growth. Furthermore, when different supply chain companies jointly adopt information disclosure strategies, they can create synergy and collectively enhance the competitiveness and image of the entire industry. Second, in previous research, the impact of decision-making models on supply chains has been widely discussed. Different companies’ cooperation can promote synergy among all parties in the supply chain and achieve resource sharing and complementarity of advantages. When facing the issue of stigma, enterprises in the supply chain can cooperate with each other to jointly develop strategies for information disclosure, coordinate resource allocation, and enhance overall competitiveness. This coordinated approach helps improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the entire supply chain, achieving a win–win situation and enhancing the overall competitiveness of the industry. At the same time, if there is a lack of coordination or trust among stakeholders, it may lead to obstacles in the decision-making process or negative outcomes.

6.2. Compared with the Previous Research

The similarities between the current study’s findings and those of previous studies include two aspects. Firstly, the research topics are related. Many previous studies have focused on technological development, quality issues, and the importance of information disclosure, aiming to understand how companies respond to market and consumer concerns about quality and performance. The model built in this study reveals how corporate decisions, particularly disclosure strategies, affect market reactions, consistent with other studies that investigate the relationship between corporate decision-making and market reactions, i.e., how a company’s strategic choices and disclosure strategies affect the behavior and attitudes of investors, consumers, and other stakeholders. Secondly, both studies emphasize the importance of information disclosure. Previous studies have recognized the importance of information disclosure in enhancing corporate transparency, boosting investor confidence, and promoting healthy market development. Furthermore, increasing numbers of studies are beginning to focus on how companies manage their reputation and brand image through information disclosure when facing issues of quality or other factors. This paper introduces disclosure level into the mathematical model to provide a more precise analysis of the specific role and impact of disclosure.

The differences between the current research findings and those of previous studies include the following two aspects. First, this study explicitly quantifies the economic impact of stigmatization. Although previous studies also addressed the negative impact of quality stigmatization on corporate revenue, they did not reveal such a clearly quantified relationship. This study provides more direct and specific evidence through building and analyzing a model, showing the negative correlation between the degree of stigma and corporate revenue, providing a more precise perspective on the economic consequences of stigmatization. At the same time, this study quantitatively analyzes the relationship between disclosure level and information asymmetry through the construction of a mathematical model and predicts the impact of different disclosure strategies on corporate performance and market reaction. Moreover, this study provides a deeper insight into the losses affecting the component manufacturer. Although previous studies also focused on the product manufacturer when faced with problems relating to quality, this study particularly emphasizes the greater losses that the component manufacturer may suffer due to the impact of quality stigmatization. This discovery reveals the different vulnerabilities of different links in the supply chain when faced with problems relating to quality, providing targeted risk management strategies for supply chain members.

6.3. Future Research Directions

Our research can be extended in the following aspects in the future. On the one hand, we did not consider the existence of competitors. In the future, scholars can consider including another competition channel and studying the impact of stigma level on the decision making and profits of enterprises in competition. On the other hand, scholars can also focus on the impact of product stigma level on specific industries. For example, scholars can focus on the new energy vehicle industry and examine how levels of stigma affect the decision making and profits of manufacturers in this sector, considering product characteristics and policy factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W.; formal analysis, J.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W.; writing—review and editing, L.Z.; funding acquisition, D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China under Grant No. 2024JC-YBQN-0759, Project of Shaanxi Social Science Foundation under Grant No.2023D017, Natural Science Research Foundation of Shaanxi Provincial Education Department under Grant No. 22JK0481, Xi ’an Social Science Foundation research project under Grant No. 24JX109, Shaanxi Province philosophy and social science research project under Grant No. 2024HZ0757, China College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program under Grant No. 202310700080X.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of Proposition 1.

Take the first partial derivative of π1 with respect to p and v, and we obtain:

We construct the Hessian Matrix of π1 for p,v as follows:

Since the first-order ordering principle submatrix of H1 is −2b < 0, and the second-order ordering principle submatrix is 4bi − q2, only 4bi − q2 > 0 can make all the odd-order ordering principle submatrix of H1 negative and all the even-order ordering principle submatrix positive. Therefore, when 4bi − q2 > 0, H1 becomes a negative definite matrix, and π1[p,v] is an concave function of p and v. That is, there exists an optimal p*, v* that makes π1 reach the maximum value.

Let ∂π1/∂p = 0 and ∂π1/∂v1 = 0; we can solve for p*, v1* as shown in (5) and (6). □

Proof of Proposition 2.

Taking the derivatives of π2 with respect to w and v2, we can solve the following:

We construct the Hessian Matrix of π2 for w,v2 as:

Since the first-order ordering principle submatrix of H2 is −b < 0, and the second-order ordering principle submatrix is 2bi − q2/4, only 2bi − q2/4 > 0 can make all the odd-order ordering principle submatrix of H2 negative and all the even-order ordering principle submatrix positive. Therefore, when 2bi − q2/4 > 0, H2 becomes a negative definite matrix and π2[w,v2] is an concave function of w and v2. That is, there exists an optimal w*, v2* that makes π1 reach the maximum value.

Let ∂π2/∂w = 0 and ∂π2/∂v2 = 0; we can solve for w*, v2* as shown in (11) and (12). □

Proof of Corollary 1.

From Table 2 we can obtain:

Since b > 0,q > 0, we can see that the denominator of p^, w^ is greater than 0, and the coefficient of their numerator u2 is less than 0. Since u ≥ 1, we can see that when u gradually increases, p^ and w^ monotonically decrease. Therefore, we can see that in cases where enterprises do not adopt quality information disclosure, the stigma level has a negative correlation with the optimal product sales price and component sales price.

Since Proposition 1 has proved that 4bi − q2 > 0, we can see that the denominators of v1*, w*, p*, v2**, w**, and p** are all greater than 0. Since the coefficients of u2 in the numerator of the above equation are all less than 0, we can see that as u gradually increases, v1*, w*, p*, v2**, w**, and p** monotonically decrease. Therefore, we can see that in the two cases of quality information disclosure by the product manufacturer and by the component manufacturer, the stigma level has a negative correlation with the optimal product sales price, component sales price, and quality information disclosure efforts of the enterprise. □

Proof of Corollary 2.

According to Table 2, we can see that in cases where the enterprise does not disclose quality information and the product manufacturer discloses quality information, the profits of the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer are as follows:

Since Proposition 1 has proved that 4bi − q2 > 0, and since b > 0, q > 0, the denominator parts of π1^, π2^, π1*, and π2*, above, are all greater than 0. From Table 2, we also obtain:

To make v1* and v2* satisfy v1* > 0,v2* > 0, it is necessary to make the numerical parts of v1* and v2* both greater than 0, which requires a + q(m − u2) − b(c1 + c2) >0.

Since a + q(m − u2) − b(c1 + c2) > 0, when u gradually increases, the π1^, π2^, π1*, and π2* numerical parts of [−a + q(u2 − m) + b(c1 + c2)]2 monotonically decrease. Therefore, it can be seen that in cases of no disclosure of quality information and cases of quality information disclosure by the product manufacturer, the stigma level has a negative correlation with the profits of the product manufacturer and the component manufacturer.

In the case of quality information disclosure by the component manufacturer, the profit of the product manufacturer is as follows:

Since a + q(m − u2) − b(c1 + c2) > 0, [−a + q(u2 − m) + b(c1 + c2)]2 decreases monotonically as u increases. Since the denominator of π1** is greater than 0, the overall π1** decreases monotonically as u increases. Therefore, it can be seen that in the case of quality information disclosure by the component manufacturer, the stigma level has a negative correlation with the profit of the product manufacturer. □

Proof of Corollary 3.

Through comparing v1* and v2**, we find that their numerators are the same, while the denominator of v2** is greater than v1*. According to Corollary 2, both the numerator and denominator of v1* and v2** are greater than 0, so we can conclude that v1*> v2**. □

Proof of Corollary 4.

From Table 3, we know that the profits of the product manufacturer in the three scenarios are as follows:

Comparing π1^, π1*, and π1**, it can be found that their numerical parts contain [−a + q(u2 − m) + b(c1 + c2)]2. Since [−a + q(u2 − m) + b(c1 + c2)]2 > 0, the sizes of π1^, π1*, and π1** can be measured through comparing the remaining parts of the equations of π1^, π1*, and π1**, namely 1/16b, i/4(4bi − q2), and 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2. The following apply: when 1/16b > i/4(4bi − q2) and 1/16b > 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2, for the product manufacturer, the profit without disclosure of quality information is better than that with quality information disclosure;

When i/4(4bi − q2) > 1/16b and i/4(4bi − q2) > 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2, the product manufacturer is responsible for disclosure of quality information and obtains higher profits;

When 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2 > 1/16b and 4bi2/(8bi − q2)2 > i/4(4bi − q2), the part manufacturer is responsible for disclosure of quality information and the product manufacturer obtains higher profits. □

References

- Ritvala, T.; Granqvist, N.; Piekkari, R. A processual view of organizational stigmatization in foreign market entry: The failure of Guggenheim Helsinki. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 282–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, W.S.; Patterson, K.D.W.; Hudson, B.A. Let’s not “taint” stigma research with legitimacy, please. J. Manag. Inq. 2019, 28, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, B.; Fang, Y.; Li, Z. Information acquisition and voluntary disclosure with supply chain and capital market interaction. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 297, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zheng, H.; Li, J. The interplay between quality improvement and information acquisition in an E-commerce supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 329, 847–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, F. Disclosure of quality preference-revealing information in a supply chain with competitive products. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 329, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.I.; Callahan, A.L. The stigma of bankruptcy: Spoiled organizational image and its management. Acad. Manag. J. 1987, 30, 405–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B.A. Against all odds: A consideration of core-stigmatized organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devers, C.E.; Dewett, T.; Mishina, Y.; Belsito, C.A. A general theory of organizational stigma. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmer, K.B.; Jones, K.S. Mental illness in the workplace: An interdisciplinary review and organizational research agenda. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haack, P.; Sieweke, J. Advancing the measurement of organizational legitimacy, reputation, and status: First-order judgments vs second-order judgments—Commentary on “Organizational legitimacy, reputation and status: Insights from micro-level management”. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2020, 6, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E. Stigma and legitimacy: Two ends of a single continuum or different continua altogether? J. Manag. Inq. 2019, 28, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, T.G.; Lashley, K.; Rindova, V.P.; Han, J.-H. Which of these things are not like the others? Comparing the rational, emotional, and moral aspects of reputation, status, celebrity, and stigma. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 444–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.K.; Howe, M.; McElroy, J.C.; Buckley, M.R.; Pahng, P.; Cortes-Mejia, S. A typology of stigma within organizations: Access and treatment effects. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.H.; Lu, C.; Yu, Y.H. Service quality, relationship quality, e-service quality, and customer loyalty in the container shipping service context: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2023, 10049060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, C.; Tracey, P. Introducing a spectrum of moral evaluation: Integrating organizational stigmatization and moral legitimacy. J. Manag. Inq. 2019, 28, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.B.W.; Zhang, M. Decision-Making Model of a Supply Chain Considering Fairness Preference and Information Sharing of the Retailer. J. Syst. Manag. 2021, 30, 552. [Google Scholar]

- Coslor, E.H.; Crawford, B.; Brents, B.G. Whips, chains, and books on campus: How emergent organizations with core stigma gain official recognition. J. Manag. Inq. 2020, 29, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnackenberg, A.K.; Bundy, J.; Coen, C.A.; Westphal, J.D. Capitalizing on categories of social construction: A review and integration of organizational research on symbolic management strategies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 375–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, B. Truthful disclosure of information. Bell J. Econ. 1982, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gilbert, S.M.; Lai, G. Supplier encroachment under asymmetric information. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Chen, Y.J. The interplay between information acquisition and quality disclosure. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2017, 26, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A. The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. In Uncertainty in Economics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.; Tan, Y. Who wants consumers to be informed? Facilitating information disclosure in a distribution channel. Inf. Syst. Res. 2019, 30, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Yu, B. Supplier selection with information disclosure in the presence of uninformed consumers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 243, 108341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, X. Equilibrium decisions for multi-firms considering consumer quality preference. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, R.N.; Mondal, S.K.; Maiti, M. Bundle pricing strategies for two complementary products with different channel powers. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 287, 701–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschstein, T.; Meisel, F. A multi-period multi-commodity lot-sizing problem with supplier selection, storage selection and discounts for the process industry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koberg, E.; Longoni, A. A systematic review of sustainable supply chain management in global supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, M. Sustainable supply chain management practices, supply chain dynamic capabilities, and enterprise performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3508–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzík, P.; Falát, L.; Zimon, D. Supply chain research overview from the early eighties to Covid era–Big data approach based on Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 109520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroufe, R.; Atkins, R.; Curkovic, S. Purchasing and supply management empowerment in the new product development process. Int. J. Value Chain Manag. 2023, 14, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.S.; Bahinipati, B.; Jain, V. Sustainable supply chain management: A review of literature and implications for future research. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).