Abstract

This research examines the evolution of human resource management (HRM) practices within Samsung and Lotte, two major South Korean conglomerates. Both companies have been profoundly influenced by the Japanese management paradigm, especially in areas like seniority-based promotion rooted in Confucian values. Drawing from institutional theory, the study elucidates how similar economic trajectories in South Korea and Japan fostered comparable institutional logics and pressures in HRM. However, as organizations navigate institutional shifts, their responses and resulting HRM adaptations can diverge. Utilizing a comparative approach through the lens of the institutional logic theory, key findings unveil as follows: (1) Samsung and Lotte’s HR practices exhibit a strong Japanese influence, highlighting cultural/historical context’s importance. (2) Despite similar pressures, the conglomerates developed distinct HR practices attributed to differing institutional logics. (3) Institutional logics play a pivotal role in shaping HRM and influencing organizational behavior. (4) Organizations adapt HR practices in response to institutional complexities, leading to practice divergence. (5) The study extends institutional theory’s application in understanding organizations’ varied responses to similar pressures. (6) Findings offer HR professionals insights on tailoring strategies based on contextual understanding. The study extends the application of institutional theory in deciphering varied organizational responses. Practically, it provides HR professionals guidance on contextually appropriate HRM strategies. Companies across Asia can leverage these insights to anticipate HR practice shifts and align them with evolving institutional frameworks.

1. Introduction

In recent years, global interest in the management practices of Korean conglomerates, such as Samsung, Hyundai Motor Company, LG, and Lotte, has grown considerably as these enterprises have showcased noteworthy success and expansion on the global stage. This heightened attention mirrors the surge of interest in Japanese corporate management practices during times when companies from Japan dominated the global market and showcased revolutionary management techniques [1]. As with the Japanese firms in the past, the international business community and academia alike are now keen to understand the unique management strategies and practices that propel South Korean businesses to international success and prominence. Moreover, South Korea’s business environment has evolved rapidly due to globalization, technological advancements, and shifting market demands [2]. Major conglomerates like Samsung, Hyundai motors, Kia, LG, SK, and Lotte have had to adapt their HR practices to stay competitive internationally. For researchers and practitioners aiming to understand and strategize for these conglomerates, recognizing the dynamics of these changes is vital [3].

Human resource management (HRM) practices are deeply influenced by the institutional environment, including the country, society, and culture, in which the company operates. Consequently, firms within the same region or country frequently exhibit similar HR characteristics [4,5]. Particularly in South Korea, the high degree of institutional pressures and homogenization means that many firms often demonstrate comparable HR practices [6]. However, even businesses with similar industrial characteristics and origins can evolve differently over time due to changing institutional logics, leading to divergent HR strategies [7]. Recent studies have explored the influence of multiple institutional logics on sustainability professionals’ work, highlighting how these logics shape their agency and the dynamic nature of their roles [8]. Furthermore, research has delved into the competing institutional logics in talent management, especially in the context of global operations, indicating significant variations in talent identification practices between headquarters and subsidiaries [9]. Additionally, the integration of socio-economic logics within supply chain networks illustrates the complex interplay of power and sustainability principles, further emphasizing the role of institutional logics in shaping sustainable organizational practices [10]. These contemporary studies enrich our understanding of how institutional logics not only influence HRM practices, but also lead to significant variations at the organizational level, addressing the gap in empirical research that compares real-world corporate examples in depth.

This research aims to address this gap by conducting a comparative analysis of two prominent South Korean conglomerates, namely Samsung and Lotte. Despite sharing similar origins and initially exhibiting comparable management styles and HR practices influenced by the Japanese management paradigm, these two companies have evolved to showcase distinct HR practices over time. By delving into these real-world corporate examples, the study seeks to elucidate the underlying reasons and processes that drive the emergence of differences in HR practices between firms operating within the same institutional environment.

For international researchers, this study offers a unique opportunity to gain insights into the dynamics of HRM practices within the context of South Korean conglomerates, which have a significant global presence and influence. By shedding light on the role of institutional logics in shaping sustainable talent management practices, the research contributes to a better understanding of how organizations navigate and adapt to institutional complexities and shifting logics, even within a highly homogenized business landscape.

Furthermore, the comparative approach employed in this study highlights the importance of examining organizational-level factors and strategic choices, rather than relying solely on industry-level or national-level generalizations. This nuanced perspective is particularly relevant for researchers interested in cross-cultural management and the interplay between institutional forces and organizational practices.

This study chooses Samsung and Lotte as the sample since Samsung and Lotte, both being influenced by Japan since their inception, have adopted business ideas and management styles from the country. While Samsung’s founders, Lee Byung-chul and Lee Kun-hee, gained insights from Japan, Lotte has consistently imported business concepts. Current interactions between Lotte’s Japanese and Korean bases highlight Japan’s enduring influence. However, their shared origins have led to unique management styles [11,12]. While research has explored similarities in HR practices between South Korean and Japanese firms [13,14], there is a notable gap in examining the differences within South Korea, especially between Samsung and Lotte. This study fills this void, delving into the reasons behind their HR divergence and the implications [15].

Founded by Lee Byung-chul in 1938, Samsung began as a small trading company in Su-dong, dealing primarily in dried-fish, locally grown groceries, and noodles. Over the decades, it diversified into various sectors, including textiles, insurance, food processing, and securities. It was in the late 1960s that Samsung entered the electronics industry, which would become its most significant and globally recognized sector. Today, Samsung stands as a paragon of success in the global business landscape, with its electronics division being one of its most profitable and influential. Its innovation-driven approach and steadfast commitment to quality have enabled it to compete at the forefront of the global electronics market, setting industry standards and continually pushing technological boundaries [16].

Lotte Group, established by Shin Kyuk-ho in 1967, has its roots as a confectionery company. Shin’s entrepreneurial spirit saw Lotte diversifying into various sectors over the years, echoing the multifaceted growth seen in conglomerates like Samsung. From its beginnings in the sweet treats sector, Lotte expanded into hospitality, retail, construction, and entertainment, reflecting its adaptability and ambition. In recent years, through strategic acquisitions both domestically and internationally, Lotte has further solidified its position as a key player in the global business arena.

The institutional logic theory posits that organizations operate under the influence of various societal-level belief systems, values, and rules that shape their behaviors and practices [17]. These institutional logics provide a framework for understanding how organizations make sense of and respond to their external environments, ultimately guiding their decision-making processes and strategic choices [18,19].

In the context of this research, the institutional logic theory offers a valuable lens for analyzing the variations in sustainable talent management practices between Samsung and Lotte, two prominent South Korean conglomerates. The theory suggests that these organizations have developed unique HR practices over time, influenced by differing business strategies, structures, and contexts [20]. By examining the institutional logics underlying each conglomerate’s approach to talent management, this study aims to unravel the complex interplay between external pressures, organizational responses, and the resulting HR practices.

Specifically, this research intends to dissect these variations in sustainable talent management practices through a comparative case study methodology. By analyzing diverse data sources, the study seeks to offer a nuanced understanding of HRM practices in both conglomerates. Employing the institutional logic theory as a theoretical framework, the study aims to highlight the role of institutional logics in shaping the HR frameworks and organizational responses to external pressures, such as societal expectations, regulatory demands, and industry norms.

This study adds to the institutional HRM discourse by highlighting the significance of institutional logics in shaping sustainable talent management practices [21]. The main research questions are How have the sustainable talent management practices evolved differently in Samsung and Lotte, despite their shared origins and initial similarities? and What are the underlying institutional logics that have shaped the divergent HR practices within these two conglomerates? By juxtaposing Samsung and Lotte’s HR frameworks, it unveils organizational responses to external pressures and provides insights into how institutional logics influence organizational decision making and strategic choices in the realm of talent management.

The insights derived from this research will benefit HR professionals, managers, and policymakers by enabling them to tailor strategies and informed policy decisions in the South Korean landscape. It enriches the academic dialogue on HRM in institutional contexts [21] and offers practical implications for practitioners and policymakers targeting sustainable business growth.

2. Literature Reviews and Method

2.1. Institutional Logic Theory

Institutional logics refer to the socially constructed norms, values, and beliefs that guide and constrain the behavior of individuals and organizations within a particular institutional environment [17]. These logics serve as a framework for understanding how organizations make sense of their environments, respond to the various pressures they face, and adapt their practices accordingly [22]. Institutional logics have been widely used in the literature to explain various organizational phenomena, including the adoption and implementation of HR practices [21].

Institutional theory posits that organizations operating within the same environment are subject to similar pressures, leading them to adopt similar practices in order to gain legitimacy and ensure survival [23]. This concept, known as isomorphism, has been used to explain the convergence of HR practices among organizations within a given institutional context [24]. However, when organizations face conflicting institutional logics or experience changes in their environments, they may diverge in their practices as they adapt to these new conditions [25].

Recent studies have highlighted the complexity of HR practices in the context of institutional logics, emphasizing how different pressures can lead to varied practices. For example, the study discusses the challenges faced by public organizations in Pakistan in implementing sustainable HR practices due to conflicting institutional logics [26]. Similarly, ref. [27] explores how logics at the field level can merge, creating hybrids that influence organizational practices. These studies suggest that organizations often navigate multiple, competing logics, leading to the development of hybrid practices [28].

When organizations encounter institutional complexity, they may adopt different responses to balance or navigate the competing demands that they face [20]. These responses can include passive conformity, active resistance, or the strategic manipulation of institutional logics [29]. Understanding the specific responses adopted by Samsung and Lotte in the face of institutional complexity can shed light on the divergent paths they have taken in terms of their HR practices. In other words, organizations may diverge in their practices when confronted with conflicting logics or environmental changes [20]. Recent research acknowledges that organizations often navigate multiple, competing logics [30], which may lead to hybrid practices [28]. This complexity is evident in the differing HR practices of Samsung and Lotte, both of which are exposed to various institutional pressures. Additionally, ref. [31] emphasizes that the ‘iron cage’ of institutionalization forces organizations to conform to varying institutional pressures, resulting in heterogeneous responses across different tiers of the supply chain.

2.2. Comparative Institutional Analysis and Institutional Logic Theory

A comparative approach to institutional analysis allows for the identification of similarities and differences between organizations operating within the same or different institutional environments [32]. By comparing Samsung and Lotte’s HR practices, this study seeks to uncover the underlying institutional logics that have influenced their development and divergence. This comparative approach can provide valuable insights into the complex interplay between organizations and their institutional environments, advancing our understanding of the dynamics that shape HR practices.

Institutional embeddedness emphasizes the idea that organizational practices are deeply rooted within the broader socio-cultural and institutional context in which the organization operates [33]. Within this framework, HR practices are not merely functional responses to organizational needs, but are shaped by the historical, cultural, and social influences of the environment. For conglomerates like Samsung and Lotte, their HR practices can be viewed as products of their institutional embeddedness, reflecting the amalgamation of global business demands and traditional Korean organizational norms [34].

While both Samsung and Lotte operate in an increasingly globalized business environment, their responses to global pressures, especially in HR practices, might differ due to their distinct organizational identities and strategies [35]. Samsung’s expansive global footprint might predispose it to adopt more globally standardized HR practices, whereas Lotte, with its deep roots in Korean culture and traditions, may exhibit a higher degree of localization in its HR approaches. Such differences underscore the importance of understanding how organizations interpret and respond to global institutional pressures in the realm of HRM [36].

Recent studies have further elucidated the impact of institutional logics on HR practices. A study examines the institutional complexity of HR practices in public organizations, highlighting the coexistence of multiple logics and their conflicting demands [26]. Similarly, a recent article discusses how institutional logics at the field level merge and create hybrids, influencing organizational practices [27]. Leadership vision and corporate strategy can also play significant roles in shaping HR practices within organizations [37]. The leadership of Samsung and Lotte, with their distinct visions and strategic priorities, might influence the HR practices that they adopt, emphasizing the different aspects of employee development, engagement, and culture. This potential divergence in leadership vision further underscores the intricate nature of institutional influences, suggesting that, while external pressures play a role, internal organizational dynamics and leadership also significantly shape the HR landscape.

Thus, the institutional logic theory offers a valuable lens through which to examine the differences in HR practices between Samsung and Lotte. Through exploring the role of institutional logics in shaping these practices, this study contributes to the growing body of literature on HRM from an institutional perspective and provides a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics between organizations and their environments. Furthermore, the insights gained from this comparative analysis can inform both academic and practical discussions on HR.

2.3. Why Comparing HR Practices in Two Companies Is Important

Understanding the dynamics of HRM practices between two companies like Samsung and Lotte holds paramount significance in both academic and practical realms. The juxtaposition of their HR strategies offers a fertile ground to deepen our comprehension of institutional theory’s applicability in HRM [38]. Given that both are subject to analogous institutional pressures, insights gleaned from how each navigates this landscape can refine the theoretical underpinnings of institutional theory concerning HRM [24].

Multiple institutional logics invariably shape organizational operations, and, by dissecting the HR practices of both conglomerates, this study will illuminate how each adapts to myriad institutional demands [30]. Their responses can, in turn, enrich the literature centered on the interplay of institutional logics within organizational practices, offering a granular view into the realm of organizational decision-making amidst conflicting pressures [28].

A comparative approach, such as employed in this study, enhances the burgeoning literature around comparative institutional analysis, particularly in HRM [32]. By distilling the nuances between Samsung and Lotte’s HRM strategies, we are poised to discern factors that drive the convergence or divergence of HR practices within a unified institutional milieu. Navigating the intricate waters of institutional complexity is a challenge faced by many organizations. Herein, comparing the HRM blueprints of Samsung and Lotte serves as a window into understanding how enterprises reconcile with these complexities-be it through conformance, resistance, or tactical manipulation of prevailing logics [20,29].

Recent studies have further contributed to this field [39]. examined talent management practices in South Korean firms, highlighting the differences between indigenous firms and foreign-owned subsidiaries and their responses to institutional pressures. This study underscores the cultural and institutional nuances that shape HR practices. Additionally, another study explored the role of corporate universities in South Korea, emphasizing their impact on HR development and their adaptation to evolving business needs [40].

Beyond the broad strokes of institutional dynamics, industry-specific elements play a pivotal role in sculpting HR practices. By juxtaposing Samsung and Lotte, which represent diverse sectors, this study endeavors to spotlight the industry-centric factors molding HR practices, even within a singular institutional framework [24]. The realm of organizational agency, especially in how it shapes HR strategies, remains a fertile ground for exploration. By evaluating the active responses of both conglomerates to institutional pressures, insights emerge on the magnitude and manner in which organizations assert their agency, crafting HR strategies that align with or defy the broader institutional script.

The tug-of-war between global influences and local dynamics is yet another dimension that this comparative analysis seeks to elucidate. The shared experience of Samsung and Lotte, both recipients of global market forces and local logics, offers a vantage point to discern the equilibrium they strike in HR practices, straddling global standards and local nuances [41]. Asia’s unique socio-cultural fabric, coupled with its economic dynamism, necessitates a deeper probe into its HRM landscape. Samsung and Lotte, as South Korean flag bearers, offer a pathway into the HRM nuances prevalent in the region, bridging gaps in the literature pertaining to non-western business ecosystems [42].

A contextual understanding of HRM underscores the need to view practices not in isolation, but as part of a larger tapestry of institutional, cultural, and strategic interplays. The juxtaposition of Samsung and Lotte underscores this, revealing the myriad factors sculpting their HRM strategies. This nuanced comprehension can challenge HRM’s universalist paradigms, driving a more tailor-made approach to HRM across diverse contexts [43]. Lastly, this study serves as a beacon for future research directions in HRM. The examination of factors influencing Samsung and Lotte’s HR trajectories can shape new avenues for research, fostering questions, and theoretical frameworks that can further the field’s depth and breadth.

3. Method and Case Setting

In this research, a comprehensive qualitative research protocol was meticulously established to guide the comparative analysis between Samsung and Lotte, with a particular focus on their chemical divisions, Samsung Chemical and Lotte Chemical. This systematic approach was anchored on the principles of methodological congruence and integrity in their framework for mixed-methods research [44]. As ref. [45] emphasizes, the rigor in the case study design involves maintaining a clear chain of evidence and addressing potential biases throughout the data collection process. The qualitative research protocol was structured as follows:

Interviewer and Interviewee Selection: For the purpose of conducting a comparative analysis, we engaged with senior HR executives and HR managers from both Samsung and Lotte. Each conglomerate was represented by four HR executives who participated as interviewees, ensuring a balanced perspective between the two entities. The interviewers, also specialized HR managers from Samsung Chemical and Lotte Chemical, were organized into a Task Force Team (TFT) format for this research endeavor (Table 1). The HR executives from Samsung possessed over 20 years of experience in human resource management within Samsung Group and Samsung Electronics. Similarly, the Lotte executives brought forth two decades of expertise from Lotte’s headquarters (HQs), with a diverse background in HR and financial operations. The HR managers, responsible for recruitment, compensation, organizational culture, and training, were selected based on a minimum of five years of tenure at their respective companies, coupled with substantial experience in HR roles. This selection criterion was established to ensure that the individuals involved in the interviews had a profound understanding of their companies’ HR practices and were capable of providing detailed insights into the operational changes pre and post the strategic merger. Their longstanding involvement in HR afforded them a historical view of the organizational practices and made them privy to the evolution of their respective HR landscapes.

Table 1.

Participant Information (example).

Interview Protocol: We conducted semi-structured interviews with senior HR representatives from both Samsung and Lotte conglomerates from May to September 2017. The interviews were audio-recorded with consent from all participants to ensure data integrity when conducting qualitative research interviews [46]. We developed a detailed interview guide rooted in the Contextual Inquiry framework [47], which included probing questions to explore the depth and breadth of HR practices. Some examples of the interview questions are as follows:

- Can you describe the changes in HR practices of your organization before and after the merger?

- What specific changes were instituted in the talent management approach following the strategic integration with the other company?

- How has the recruitment and selection process evolved over time in your organization?

- Can you elaborate on the performance evaluation criteria and processes used for employees at different levels?

- What are the key factors considered in determining compensation and rewards for employees?

- How does your organization approach leadership development and succession planning?

- What roles do cultural factors or organizational values play in shaping HR practices in your company?

- How does your organization respond to external pressures or changing market dynamics when it comes to HR practices?

- Can you describe the decision-making process and governance structure for HR-related policies and practices?

- In what ways do you believe your organization’s HR practices differ from or align with industry norms or best practices?

This approach ensured a rich, in-depth collection of qualitative data from the senior HR representatives of both conglomerates. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to preserve data integrity, with consent from all participants, adhering to the guidelines [45] on conducting qualitative research interviews.

Audit Trail: An audit trail was rigorously maintained throughout the study, capturing the research process, decisions made, data collected, and analysis steps. This was in line with the recommendations [48] for establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research. The audit trail included detailed notes on the selection of participants, the development of the interview guide, the coding of transcripts, and the synthesis of findings.

Instrumentation: The primary instrument for data collection was the semi-structured interview, complemented by a thorough document analysis protocol [49]. We utilized NVivo (version: NVivo 14) [50], which is a qualitative data analysis software, to facilitate systematic coding and theme development, enhancing the reliability and validity of the data analysis process [51].

Additionally, secondary data were meticulously collected through a comprehensive review of archival records, including official corporate documents, annual reports, and industry publications such as [52,53] and others. This process was informed by established principles of document analysis as a method for qualitative research, ensuring systematic examination and interpretation [54]. Following the guidelines set forth by [55] for qualitative data analysis, documents were subjected to open coding in order to identify themes and patterns relevant to the HR practices of both organizations.

As for case setting, Samsung Chemical, originally established in 1954 as Jeil Mojik, ventured into the apparel business in 1976. By 1989, it expanded its operations by entering the chemical business through Jeil Mojik Chemical. Subsequent pivotal moments for the company were its merger with Samsung SDI in July 2014 and its chemical business spin-off in February 2016. In May 2016, it integrated into the Lotte Group. As of 2016, the company reported a revenue of KRW 2.57 trillion. Samsung’s core business areas include ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene), which constitutes 53% of its operations, and is predominantly utilized in vehicles, refrigerators, and office automation. Another significant segment is PC (Polycarbonate) at 39%, used primarily in mobile and TV IT products, followed by construction materials at 8%. As of December 2016, Samsung employed a total of 1184 individuals, 41% of whom were involved in production, 26.4% in sales, 17.2% in support, and 15.5% in research. Notably, 17% of its workforce comprises female talent, and 21% hold either a Master’s or Doctoral degree.

Lotte Chemical was founded in 1976, and Lotte completed its first plant by 1979. From 1988 to 1991, the company expanded its factories and diversified its product range. Between the 1990s and 2000s, Lotte further augmented its operations through vertical integration, the establishment of a second factory, and business diversification via both domestic and international mergers and acquisitions. By 2016, Lotte reported a standalone revenue of KRW 8.26 trillion. Its primary business is divided among Monomers (39%), utilized widely as raw and chemical products, Polymers (38%), used in various products as synthetic resins, Aromatics (13%), which include aromatic products of ethylene raw material, and other businesses (9%), such as precision chemicals and special resins. As of December 2016, Lotte’s workforce consisted of 2857 employees. A breakdown reveals 48% in production, 36% in business management, 7% in specialized research, and 9% in sales, support, and contracts. Of these, 12% are female professionals, and 15% have advanced academic degrees.

4. Findings

4.1. HR Governance

HR governance practices are reflective of a company’s overarching organizational culture, values, and strategic focus. An analysis of the HR practices of two major conglomerates, Samsung and Lotte, reveals distinct differences in their governance structures, underscored by their unique institutional logics.

4.1.1. Implications of Organizational Size and Structure

The data suggest that the size and structure of the conglomerates play a pivotal role in shaping their HR governance. Samsung, with its extensive employee base and numerous affiliates, appears to centralize certain HR decisions at the group level, possibly to maintain uniformity and control across its vast empire. This is especially evident in areas like global education and organizational diagnostics. Conversely, Lotte, characterized by a higher number of smaller affiliates, seems to allow more autonomy to its subsidiaries in HR matters, though with some apparent constraints in autonomy.

“Samsung’s focus on executive and key talent management is a direct response to its expansive workforce and numerous affiliates, which surpass the capacity for detailed oversight typically exercised within a group structure (Participant 1).”

“Autonomy in recruitment systems is a hallmark of Samsung’s HR governance, with individual affiliates empowered to tailor their hiring processes while still operating under a broader governance framework (Participant 2).”

“Samsung demonstrates a collaborative decision-making process in critical HR tasks such as recruitment and promotion, often requiring close coordination between the conglomerate’s headquarters and its affiliates (Participant 5).”

“Lotte feels the constraints of autonomous operation more acutely due to the smaller scale of its affiliates and a relative lack of internal capabilities, often resulting in perceived limitations in self-directed management (Participant 6).”

“Recruitment and rank promotion systems within Lotte are more centralized, reflecting a governance approach that consolidates control over these key HR functions (Participant 8).”

“Particularly evident in Lotte’s reward system is a tendency towards tight group-level management, suggesting a preference for a more controlled and uniform approach to compensation across the conglomerate (Participant 10).”

4.1.2. Key Differences in HR Governance

The most pronounced divergences between Samsung and Lotte’s HR governance lie in three main areas as follows: recruitment systems, rank/promotion systems, and compensation systems. Lotte displays a higher level of involvement in its subsidiaries’ HR operations, particularly in these areas. This could be attributed to Lotte’s attempt to standardize practices across its myriad of smaller affiliates, ensuring coherence in HR strategies. Samsung, with its vastness, seems to prioritize the management of its executives and global talent to ensure that leadership is aligned with group-wide objectives.

4.2. Job System

4.2.1. Key Differences

Samsung and Lotte, two of South Korea’s largest conglomerates, have distinct approaches to their job systems, reflecting their organizational strategies and historical development. While there exists a standardized job system for both executives and employees across the group, individual affiliates have the flexibility to choose from this standard system. Specifically, for executives, there are four job categories, twenty-seven job types, and seventy-four job roles, while, for regular employees, the system diversifies into nine job categories, one hundred and seven job types, and a staggering seven hundred and twenty-two job roles. A noteworthy observation is Samsung’s limited use and low utility of job description documents. These are primarily employed during job rotations or group management evaluations. Despite having a common framework, Samsung’s future direction appears to be leaning towards customizing job systems for individual affiliates, hinting at a shift towards a role-based HR approach.

For Lotte’s job system, contrasting Samsung’s structure, Lotte’s system has four main categories, which are expanded into seventeen job types and one hundred and thirty-nine specific job roles. Similar to Samsung, they also employ four job categories, twenty-six job types, and eighty-one job roles for regular employees. However, a distinguishing feature of Lotte’s approach is the reflection of specific characteristics of individual business units and subsidiaries in its job system. Even though they manage job descriptions through a system, the frequency of updates is relatively low, indicating a possibly static nature of job roles or a less dynamic HR environment.

Both conglomerates operate with the overarching objective of enhancing the manageability across their vast arrays of subsidiaries through a standardized job system. However, while Lotte focuses on tailoring its job system to reflect the individual characteristics of its various business units, Samsung is displaying an inclination to differentiate job systems even further among its affiliates. This divergence underscores the contrasting institutional logics that underpin the HR strategies of the two giants, with Samsung possibly emphasizing adaptability and specificity, while Lotte stresses uniformity and consolidation.

“Samsung Group maintains a standardized job classification system that is applied across the conglomerate but allows individual affiliates to select from this system to suit their specific needs. Specifically, for executives, the system is categorized into four job groups, 27 job types, and 74 job roles, while for general employees, it expands into nine job groups, 107 job types, and an extensive 722 job roles (Participant 4).”

“The operation of a standardized job classification system across the Samsung Group points to a centralized approach to HR governance, reflecting an organizational culture that values uniformity and consistency across its diverse operations (Participant 5).”

“Lotte’s job classification system is comprised of four job groups, 17 job types, and 139 job roles, which suggests a more streamlined approach compared to Samsung’s extensive categorization (Participant 7).”

“Lotte adopts a more customized approach to its job classification system, which takes into account the unique characteristics of each business unit and subsidiary, thereby demonstrating a decentralized approach that allows for greater specificity and responsiveness to the varied operational demands within the conglomerate (Participant 8).”

4.2.2. Interpretation

From the institutional logic perspective, job systems, as evidenced by the contrasting models of Samsung and Lotte, can be perceived as manifestations of broader organizational beliefs, values, and practices. Institutional logics act as guiding frameworks, shaping the choices that organizations make and the paths they tread [19]. Samsung’s shift towards a role-based HR approach, as indicated by its propensity for customization among affiliates, could be interpreted as a nod to an institutional logic that values adaptability and specificity. Such a logic places an emphasis on responsiveness to dynamic environments, aiming to harness the unique strengths of individual entities within the conglomerate.

Lotte, on the other hand, showcases a different set of underlying institutional logics. Its emphasis on a system that mirrors the individual characteristics of its diverse business units, yet maintains a semblance of standardization, speaks to a logic that cherishes uniformity and consolidation. This approach, while ensuring alignment with overarching corporate objectives, also accentuates the inherent strengths and nuances of each business unit, possibly aiming for a harmony between individuality and cohesion [22]. The variations in the job systems of both conglomerates underscore the influence of differing institutional logics, guiding their HR practices and long-term strategic visions.

Recent studies have provided further insights into how institutional logics shape HR practices. Ref. [26] explored the institutional complexity of HR practices in public organizations, emphasizing the coexistence of multiple logics and their impact on HR effectiveness. Similarly, ref. [27] discussed how field-level institutional logics merge and create hybrids, influencing organizational practices. These studies highlight the nuanced interplay between institutional pressures and organizational responses, shedding light on how Samsung and Lotte navigate these dynamics in their HR systems.

4.3. Promotion

4.3.1. Promotion Process Management

At Samsung, individual subsidiaries have the autonomy to decide the table of organization (TO) for promotions and the final list of promotees. The group-level oversight is limited to providing a general guideline on the promotion rate and overseeing the talent promotion process. This is evident from Samsung’s practice where the promotion rate is generally shared as a range of around 30–40%. In contrast, Lotte underwent a shift in its promotion process management in 2017. While they manage the promotion TO, the final list of promotees is not overseen by group-level management.

“Within the Samsung Group, promotion rates are meticulously managed at the group level, indicating a centralized approach to career progression oversight. This practice suggests a strategic intention to maintain consistency in advancement opportunities across the conglomerate (Participant 3).”

“Despite the centralized control, individual affiliates within the Samsung Group are known to rapidly promote key talents, with the conglomerate overseeing these promotion rates. This dual approach reflects a blend of group-level standardization and subsidiary-level agility in nurturing and advancing high-potential employees (Participant 4).”

“Lotte encourages its subsidiaries to manage their promotion rates, implying a decentralized system of HR governance. This method suggests a philosophy that empowers individual subsidiaries to tailor promotion practices to their unique operational needs and talent landscapes (Participant 9).”

“Regarding the management of key talents, the Samsung Group not only monitors the numbers centrally but also maintains a separate roster for these high-value individuals. This indicates a structured approach to talent management, where the group retains a macro-level view of key personnel while still allowing for targeted development and recognition at the subsidiary level (Participant 6).”

4.3.2. Promotion Eligibility Criteria and Review Process

Samsung’s criteria for promotion are multi-faceted. An employee’s eligibility is determined via achieving a set number of promotion points which are specific to their rank. Additionally, certain conditions can lead to exclusion from promotion, such as being on leave during the promotion eligibility date (with some exceptions like parental leave), disciplinary actions, and not achieving the required promotion points. On the other hand, Lotte employs a simpler criterion, focusing on the standard tenure associated with a particular rank. However, exclusions are made for those who have received a “D” grade (lowest performance) in the previous year’s performance review and those who have not completed the required promotion qualification courses. The evident difference here is Samsung’s point-based system, which minimizes the administrative efforts by automatically filtering out those with low performance scores or those who have been in a particular rank for an extended period.

Samsung’s promotion review gives weight to performance evaluations, education, and HR discussion sessions. Additional points are awarded for rewards and language skills, while penalties are imposed for disciplinary actions. In contrast, Lotte’s review process places importance on performance evaluations, with additional points being awarded for rewards, language proficiency, current position, organizational evaluations by the CEO, job qualifications, and recommendations from the HR committee.

“At Samsung, employees become eligible for promotion once they meet a set promotion point threshold specific to their rank. This point-based system indicates a meritocratic approach where quantifiable achievements are used to gauge advancement readiness (Participant 2).”

“Lotte determines promotion eligibility based on the fulfillment of standard tenure for each rank. This suggests a system where time and experience within a certain rank are key determinants for progression, reflecting a more traditional and possibly tenure-based approach to career advancement (Participant 8).”

“Samsung’s primary criteria for promotion evaluation hinge on HR assessments, with additional credits given for commendations and language proficiency. Conversely, demerits are applied for disciplinary actions and lack of language skills. This structure underscores the importance Samsung places on both performance and extracurricular competencies as indicators of an employee’s readiness for promotion (Participant 4).”

“Lotte’s evaluation criteria for promotions are also rooted in HR evaluations, but with additional factors that include commendations, language proficiency, holding a key position, passing job qualification exams, and organizational evaluations by the CEO. The broader range of considerations points to a more holistic assessment of an employee’s contributions and potential within the company’s structure (Participant 9).”

4.3.3. Interpretation

Understanding the nuances in the promotion strategies of Samsung and Lotte through the lens of institutional logic offers a profound examination into their organizational values, beliefs, and practices that form the bedrock of their human resource decisions. Institutions define the rules and establish normative frameworks that organizations operate within, guiding them through complex strategic decisions, including promotion criteria and processes [56]. Samsung’s approach, characterized by decentralized decision making and a structured point-based system, embodies an institutional logic that emphasizes autonomy, meritocracy, and specificity. By affording individual subsidiaries the discretion to make promotion-related decisions and focusing on quantifiable metrics, Samsung underscores the institutional values of adaptability, agility, and the pursuit of excellence [57].

In contrast, Lotte’s approach to promotion is demonstrative of a different institutional logic. The transition in its promotion process management in 2017 and its comprehensive review criteria, which factors in both individual performance and organizational evaluations, reflect a holistic, integrative approach. This implies an underlying institutional logic that values not just individual merit, but also organizational cohesion and collective responsibility. By incorporating broader criteria such as CEO evaluations and recommendations from the HR committee, Lotte underscores the institutional importance of aligning individual achievements with broader organizational goals and values [20]. These contrasting strategies underscore how institutional logics can profoundly shape even intricate HR practices like promotion, determining the ways in which conglomerates recognize and reward their workforce.

Recent studies further highlight the impact of institutional logics on HR practices. Ref. [58] discusses the updated concepts in HRM, such as unconscious bias and platform work, which influence current organizational practices. Additionally, ref. [39] examines the distinctions in talent management practices between South Korean and foreign-owned firms, revealing how local institutional logics shape HR strategies. These insights reinforce the view that institutional logics significantly shape HR strategies and practices in large conglomerates like Samsung and Lotte.

4.4. Recruitment and Selection

4.4.1. Document Screening and Interview Process

Samsung’s approach to the initial document screening is designed for efficient candidate filtration, focusing primarily on meeting the minimum qualification criteria. Their subsequent stages involve a written aptitude test (GSAT) to gauge job-related knowledge, and various interviews (including competency, executive, and creativity interviews) to assess job expertise, integrity, talent fit, and creativity. Contrarily, Lotte adopts a more meticulous document screening process, considering the number of interviewees. Their subsequent steps involve an aptitude test (L-TAB) to determine the organizational and job fit, as well as competency interviews, which also include an executive interview and a foreign language oral test. While both conglomerates seek to ascertain candidates’ job suitability, alignment with the company’s values, and overall compatibility, their methods and focus areas diverge. Samsung’s emphasis on creativity and Lotte’s on language proficiency underscore their distinct organizational priorities.

“Samsung Group’s recruitment process initiates with a document screening phase where the applicant’s eligibility is ascertained by verifying minimum qualifications through the application and cover letters. This step illustrates the conglomerate’s emphasis on ensuring that all candidates meet a set baseline of requirements before moving forward in the hiring process (Participant 4).”

“Furthermore, Samsung conducts the GSAT, an aptitude test designed to assess the level of job-related knowledge necessary for the roles they are hiring for. This indicates a systematic approach to evaluating candidates’ competencies, aligning with a data-driven recruitment strategy (Participant 5).”

“Lotte’s document screening process involves a meticulous review of each candidate’s qualifications, with a pronounced consideration for the number of applicants they intend to interview. This suggests a highly selective and strategic approach, potentially aiming to balance the quality of candidates with the practicalities of the interview process (Participant 7).”

“Lotte utilizes the L-TAB, a personality and cognitive ability assessment, to gauge a candidate’s fit with the organization and the specific job function. The use of such assessments indicates Lotte’s commitment to understanding the holistic profile of each applicant, ensuring that they not only have the skills required but also align with the company’s cultural and operational ethos (Participant 10).”

4.4.2. Criteria Emphasized in Document Screening

Both Samsung and Lotte prioritize the confirmation of minimum qualifications, job suitability, and the alignment of the applicant’s values with the company’s during document screening. However, their evaluation mechanisms differ. Samsung employs multiple operational staff to meticulously review each application, further leveraging an essay verification system (EWS) under the group’s oversight, which is sensitive to organizational and societal issues. In contrast, Lotte’s entire document screening process is managed by the Group Talent Acquisition Committee, indicating a centralized approach. This divergence might suggest Samsung’s intention to ensure a more decentralized, ground-up evaluation, while Lotte seeks to maintain consistency and coherence through centralized oversight.

4.4.3. Written Examinations, Personality Assessments, and Interview

Samsung’s GSAT, a written aptitude test, aims to measure the core competencies which are crucial for specific jobs without distinguishing between arts and science backgrounds. Their personality assessment, conducted on the interview day, targets factors influencing organizational life. On the other hand, Lotte’s L-TAB gauges the necessary work abilities with a division between arts and science disciplines, and evaluates the personality traits which are essential for organizational life before the interview. While both groups leverage written and personality tests to discern candidates’ aptitude and organizational fit, the timing, structure, and focus areas of these tests reflect their distinct institutional logics. Samsung’s decision to administer the personality test on the interview day, juxtaposed with Lotte’s pre-interview approach, might suggest differing views on the interplay between inherent traits and interview performance.

“Within Samsung, multiple HR representatives from various affiliates are involved in the initial document screening process, indicating a collaborative approach. Additionally, the group employs a proprietary essay verification platform that screens for organizational understanding and awareness of social issues, suggesting a thorough and comprehensive review process that goes beyond basic qualifications (Participant 1).”

“At Lotte, a dedicated recruitment task force team organized by the headquarters intervenes in all document screenings, implying a centralized and meticulous control over the selection of candidates, which may aim to ensure a uniform standard of candidate evaluation across the conglomerate (Participant 6).”

“Samsung mandates that all candidates who pass the document review must undertake the GSAT, an aptitude test that measures the job-specific competencies deemed crucial for the role. This universal application of the GSAT indicates a consistent and standardized approach to assessing candidate suitability (Participant 2).”

“The GSAT not only assesses cognitive abilities across 160 items covering verbal reasoning, mathematical reasoning, inference, visual thinking, and general knowledge within 140 min but also includes a personality assessment with 300 items conducted online on the day of the interview. This two-pronged assessment underscores Samsung’s emphasis on a holistic understanding of a candidate’s capabilities and personality traits (Participant 4).”

“Lotte’s L-TAB evaluates cognitive abilities through tasks in language comprehension, problem-solving, data interpretation, verbal reasoning, and spatial reasoning, encompassing a total of 135 items over 145 min. The personality assessment for Lotte, consisting of 265 items, is administered prior to the interview day within 90 min, reflecting an approach that values a preemptive understanding of the candidate’s traits (Participant 8).”

“Samsung’s interviews are exclusive to individuals who have demonstrated high performance within the organization and have completed specific training and evaluations, which suggests a selective and merit-based approach to candidate advancement in the interview process (Participant 4).”

“For Lotte, interview participation is limited to those who have completed an interviewer certification process and are identified as high performers, indicating a structured and performance-oriented criterion for involvement in the selection process (Participant 7).”

4.5. Evaluation

4.5.1. Evaluation Structure and Weightage

Both Samsung and Lotte structure their evaluations around achievement (performance) and competency (capability). However, they differ in the weightages assigned to each aspect. Samsung maintains a 50-50 split between achievement and competency for most of its evaluations. For certain roles, it modifies this ratio to 66.6% for achievement and 33.3% for competency. Lotte, on the other hand, varies its weightage more extensively based on roles, ranging from a balanced 50-50 split to being as skewed as 30–70 in favor of competency for some positions. This divergence might be rooted in their distinct institutional logics as follows: Samsung’s approach leans towards an even-handed evaluation of what an employee has achieved versus their potential, while Lotte, in certain roles, places a greater emphasis on potential, possibly due to the nature of tasks or the dynamics of the job environment.

“At Samsung, the performance evaluation system is balanced, with an equal 50% weight given to both achievement and competency evaluations. The evaluation is detailed, consisting of five items for achievement and fourteen for competency, and is conducted annually. This parity in evaluation criteria underscores a comprehensive appraisal approach that seeks to equally measure what employees accomplish and their capabilities (Participant 2).”

“Lotte’s approach to performance evaluations varies depending on the job rank, with a 70% focus on achievement for leaders and an even 50-50 split for managers. The number of items in the achievement evaluation is aligned with the Management By Objectives (MBO) approach, while competency is assessed using twelve items. These evaluations are also administered annually, reflecting a tiered approach that adapts the emphasis on achievement and competency according to the level of responsibility (Participant 6).”

4.5.2. Application of Evaluation Results

In Samsung, both achievement and competency evaluations influence the basic pay. Additionally, individual performance bonuses exist across the board, with company-wide performance bonuses being influenced by the achievement evaluations. Promotion, position appointments, and training are all linked to both achievement and competency evaluations. Lotte, in contrast, does not reflect achievement or competency evaluations in the basic pay. Instead, individual and company-wide performance bonuses are tied to achievement evaluations. This differential approach suggests that, while Samsung sees evaluations as a holistic tool influencing multiple facets of an employee’s journey, Lotte employs them in a more targeted manner, primarily for bonus calculations.

“Samsung allocates a higher proportion of favorable ratings to top performers, signaling that receiving lower-than-average ratings is a clear directive for the employee to exit the company. This practice indicates a performance-driven culture where exceptional results are highly rewarded, and underperformance is not tolerated (Participant 1).”

“Samsung does not engage in organizational evaluations but emphasizes differential individual assessments. This highlights a culture that values individual contributions and differentiates employee rewards based on personal performance (Participant 5).”

“Lotte incorporates organizational evaluations into its appraisal process. This inclusion suggests a philosophy that recognizes the collective efforts of groups or teams, alongside individual performance, in achieving company objectives (Participant 8).”

“Lotte adheres to a normal distribution for rating proportions in evaluations, which may suggest a more standardized approach to performance assessments across the organization (Participant 9).”

4.5.3. Interpretation

Evaluation, a crucial component of human resource management, encapsulates an organization’s values, beliefs, and priorities. Samsung and Lotte, although originating from the same national context, portray variations in their evaluation practices, which can be interpreted through the prisms of institutional logics. At its core, institutional logic offers insight into the foundational principles that guide an organization’s decisions, embodying broader societal and industry-based ideologies [5]. Samsung’s balanced emphasis on both achievement and competency mirrors an institutional logic that values both present contributions and future potential. The decision to eschew organizational evaluations, focusing on individual metrics, further underscores a predominant belief in individual agency as a primary driver of corporate success. Such an evaluation system speaks to a meritocratic logic that equates individual contributions to organizational outcomes, reflecting a corporate culture valuing individual innovation and impact [23].

Lotte, conversely, displays a propensity to lean heavily on competency in specific roles, possibly reflecting the organization’s deeper commitment to nurturing potential and fostering growth. By incorporating organizational evaluations, Lotte illustrates an institutional logic that emphasizes collective harmony, teamwork, and the interdependencies within an organization, suggesting the idea that organizational success is a symbiotic outcome of individual and team efforts [59]. Their targeted application of evaluation outcomes, primarily focusing on bonuses, indicates an intent to motivate and reward tangible achievements. Both conglomerates, through their contrasting evaluation methodologies, showcase how deep-rooted institutional beliefs and values guide, shape, and influence the intricate processes of human resource management.

Studies further highlight the impact of institutional logics on HR practices. For instance, ref. [60] examines how competing logics influence HR effectiveness and employee turnover, providing insights into the complex interplay of different logics within organizations. Additionally, ref. [27] discusses how field-level institutional logics merge and create hybrids, influencing organizational practices. These insights reinforce the view that institutional logics significantly shape HR strategies and practices in large conglomerates like Samsung and Lotte.

4.6. Reward and Compensation

4.6.1. Base Salary Structures

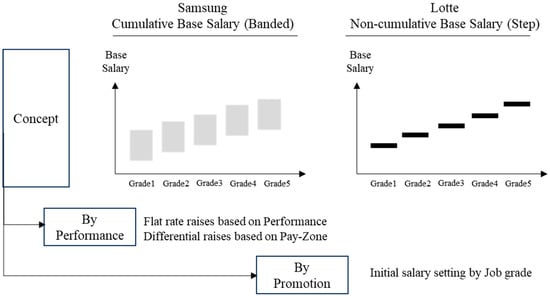

Samsung adopts a meritocratic approach to its base salary, with an emphasis on “Merit Increase” within a defined “compensation band”. This approach underscores performance-driven rewards, suggesting a belief in individual merit and a desire to foster a competitive, performance-oriented culture. In contrast, Lotte’s approach emphasizes equality at each job level, with the philosophy that “equal rank equals equal pay”. Such a practice suggests an institutional logic that values role-based consistency and might aim to promote cohesion within job groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The difference in the base salary setting methods.

“Samsung implements a Merit Increase policy for individual employees and utilizes a compensation band to guide reward amounts. This method reflects a tailored approach to compensation, where individual performance is a significant determinant in salary increments, allowing for personalized rewards within predefined ranges (Participant 4).”

“Lotte maintains uniform basic pay within the same job ranks. This practice suggests a compensation philosophy that emphasizes parity and consistency across employees holding similar positions, potentially fostering a sense of equity and standardization (Participant 7).”

4.6.2. Performance Bonuses and Incentives

Both Samsung and Lotte employ a combination of company-wide and individual performance bonuses. Samsung’s structure includes both a company-wide performance bonus based on overall company objectives (PI) and another based on profit generation (PS), reflecting an emphasis on both strategic alignment and profitability. They also incorporate an individual performance bonus, reinforcing the importance of individual contribution. The calculation of Samsung’s PS involves sophisticated financial metrics such as EVA (Economic Value Added), highlighting their focus on financial value creation. Lotte, on the other hand, offers a company-wide performance bonus (Management Performance Bonus) and an individual performance bonus (Performance Bonus), indicating a simpler yet comprehensive approach to aligning individual and organizational goals.

“Samsung compensates its employees with a bonus calculated as 600% of the basic salary and fixed overtime pay, disbursed monthly. This generous bonus structure points to a performance incentive system that significantly rewards employees beyond their regular pay (Participant 5).”

“For performance bonuses, Lotte integrates business outcomes, individual performance evaluations, and organizational assessments to determine the payout of performance bonuses. This comprehensive bonus system indicates a blended approach where both individual contributions and collective results are recognized and rewarded (Participant 8).”

4.6.3. Interpretation

Reward and compensation practices serve as a testament to an organization’s core beliefs and principles, providing insights into the underlying cultural, strategic, and institutional influences that shape its HR decisions. The contrasting practices of Samsung and Lotte provide a vivid illustration of how institutional logics mold the fabric of HR strategies, even within organizations operating in similar socio-cultural environments. Samsung’s alignment with a meritocratic logic, as seen in their base salary structures, suggests an organizational culture where individual excellence is incentivized and value creation is of paramount importance [56]. The use of EVA as a performance metric further indicates an intricate commitment to ensuring returns above the cost of capital, emphasizing not only profitability, but efficient resource allocation, which aligns with a modernist capitalist logic [22].

Lotte, with its egalitarian salary approach, resonates with an institutional logic that prioritizes role consistency and organizational cohesion. Such a strategy could be indicative of a belief system that values harmony, fairness, and collective welfare, fostering a sense of unity among employees of the same rank [23]. Moreover, Lotte’s less complex yet comprehensive bonus structure, focusing on both individual and organizational goals, further accentuates an institutional logic that seeks a balanced approach, nurturing individual talent while also ensuring organizational growth and stability. Both Samsung and Lotte’s reward and compensation practices are emblematic of the deep-seated institutional logics that shape their HR strategies, offering a profound lens into their organizational psyche and priorities. Furthermore, ref. [61] underscores that effective HRM practices significantly enhance operational performance, with variations observed across different countries and industries.

4.7. Human Resource Development Focusing on High Performer Development

4.7.1. Specialist Development

Samsung’s approach to developing its workforce emphasizes nurturing job-specific experts, often referred to as a “T-shaped” model. This strategy focuses on deepening employees’ expertise in a specific domain, while also broadening their skills across related areas. Such an approach suggests that Samsung values deep technical and domain-specific knowledge, aiming for mastery in specific roles. Contrarily, Lotte emphasizes the cultivation of industry experts through a rotation system. By frequently rotating employees through various positions, Lotte hopes to develop professionals with a broad understanding of the industry, reflecting an institutional logic that values versatility and a holistic understanding of the business landscape.

“Samsung places significant emphasis on strengthening core job expertise in its career development pathways. After enhancing these specialized skills, the conglomerate values the accumulation of related job experiences, suggesting a strategic focus on building deep professional competencies followed by a breadth of experience (Participant 4).”

“Lotte demonstrates a tendency toward fostering a range of competencies by continuously rotating employees through various job functions and leadership roles. This approach indicates a commitment to developing versatile employees with a broad spectrum of experiences (Participant 8).”

4.7.2. High Potential Talent Management

Samsung’s talent management strategy is more comprehensive and rigorous. They identify their top talent based on a multi-faceted assessment, which includes an HR session involving the CEO and the HR committee. This indicates the high importance that Samsung places on nurturing and retaining top talent, to the extent that its CEO’s performance evaluation is significantly influenced by talent management outcomes. On the other hand, Lotte’s approach is in its nascent stages, primarily relying on performance evaluations and business unit recommendations. While both companies maintain confidentiality regarding their talent pools, Samsung’s approach emphasizes the critical role of top talent in the company’s strategic direction.

“In managing its key talent, Samsung identifies the top 20% of performers as part of its selection pool based on evaluation results. The conglomerate further employs a multi-rater diagnostic that includes peer and supervisor assessments, comprehensive competency evaluations, and HR sessions that involve the CEO, underlining a holistic and top-tier engagement in talent management (Participant 3).”

“Samsung maintains confidentiality regarding key talent status, choosing not to disclose this to the individual employees and restricting this knowledge to the highest levels of management and HR departments. This practice points to a discrete and strategic approach to managing high-potential talent (Participant 4).”

“Lotte defines its core talent as the top 30% based on group guidelines, with identification rooted in performance appraisals and business unit recommendations yet retains confidentiality from the individuals concerned. This method reflects a structured, performance-based talent recognition system that aligns with group standards while keeping potential key talent designations internal (Participant 9).”

4.7.3. Succession Planning

Succession planning at Samsung is geared towards identifying potential successors not only for the CEO and critical posts, but also for key managerial positions. Their criteria for selection include comprehensive executive evaluations and recommendations from current position holders. Samsung’s emphasis on strategic job placements, advanced managerial training, and external coaching indicates a proactive approach to ensuring seamless leadership transitions. Lotte’s approach to succession planning, while more streamlined, also underscores the importance of strategic job placements and merit-based promotions. Their focus on recommendations from the CEO and HR divisions suggests a top-down approach, reflecting an institutional logic that values centralized decision making.

“Samsung has established a systematic approach to nurturing CEO candidates by utilizing a pool of potential successors, a listed group of candidates, and a cohort for next-generation leaders. This tiered structure indicates a proactive and planned strategy for executive succession (Participant 1).”

“Within Samsung, candidates for executive and key leadership positions are distinctly classified into first and second priority rankings. Such a system suggests a well-organized and transparent approach to succession planning, providing clarity in the pathway to leadership roles (Participant 1).”

“The selection criteria for these high-potential candidates are stringent, with eligibility being contingent upon receiving an ‘A’ grade in comprehensive executive evaluations. This criterion underscores the emphasis on proven performance and the meritocratic nature of Samsung’s leadership development (Participant 2).”

“The developmental programs for these candidates involve strategic job placements and priority enrollment in in-house management training courses, supplemented by external and CEO coaching. This multi-faceted approach reflects Samsung’s commitment to equipping future leaders with a diverse and robust set of skills and experiences (Participant 2).”

“Lotte does not have a specific process or program designated for CEO selection. The absence of a formalized pathway suggests a potentially more ad-hoc or situational approach to executive succession within the conglomerate (Participant 6).”

4.7.4. Interpretation

Samsung and Lotte, as frontrunners in the South Korean corporate landscape, encapsulate divergent approaches towards human resource development, especially concerning high performer nurturing. Their strategies, when viewed through the institutional logic’s perspective, shed light on deeper organizational beliefs and priorities that have evolved over time. Samsung’s prioritization of the “T-shaped” model—specializing in a particular domain while maintaining competency across peripheral areas—highlights its commitment to producing masters in specialized roles, embodying an institutional logic that champions technical excellence and in-depth knowledge [17]. This expertise-driven approach contrasts starkly with Lotte’s rotational system, aiming to develop all-rounders with comprehensive industry insights. Such a method aligns with an institutional logic that sees value in versatility, promoting adaptability and a broader organizational perspective, echoing the traditional beliefs of holistic talent management [23].

Furthermore, Samsung’s meticulous approach to high potential talent management, involving even the CEO in assessments, illuminates its strategic emphasis on cultivating top-tier talent. The fact that a CEO’s performance evaluation is intertwined with talent management outcomes underscores the critical role that top talent plays in driving Samsung’s strategic goals, resonating with an institutional logic that interlinks organizational leadership with talent cultivation. Meanwhile, Lotte’s nascent, performance-centric approach towards talent management hints at an evolving institutional logic, possibly in transition, that values consistent performance, but might be moving towards a more comprehensive talent development strategy. As both conglomerates navigate the intricate waters of human resource development, their distinct strategies not only reflect their current organizational priorities, but also hint at the future trajectories shaped by deeply ingrained institutional logics [60], and examine how competing logics influence HR effectiveness and employee turnover, providing insights into the complex interplay of different logics within organizations. Additionally, ref. [26] discusses the institutional complexity of HR practices in public organizations, emphasizing the coexistence of multiple logics and their conflicting demands. These insights reinforce the view that institutional logics significantly shape HR strategies and practices in large conglomerates like Samsung and Lotte.

4.8. Summary

In examining the human resource practices of two South Korean conglomerates, Samsung and Lotte, clear distinctions emerge across several key HR dimensions (Table 2). Samsung’s approach predominantly leans towards centralization and meritocracy. This is evident in its centralized HR governance, a comprehensive job system that provides flexibility for affiliates, and a rigorous, performance-based recruitment and selection process. Moreover, Samsung’s evaluation system maintains a balanced focus on achievement and competency, with a reward structure that emphasizes individual merit and economic value creation. In terms of human resource development, the conglomerate adopts a “T-shaped” model for specialist development, emphasizing both the depth and breadth of skills. Recent studies support these practices, highlighting the effectiveness of centralized governance and performance-based recruitment in enhancing organizational performance [62].

Table 2.

Summary of Samsung and Lotte HR practices.

Contrastingly, Lotte’s practices often veer towards decentralization, with a specific emphasis on role-based consistency in the reward system and traditional recruitment methods. Their job system, while less expensive than Samsung’s, is tailored to reflect the unique characteristics of individual business units. In the realm of promotions, Lotte employs a more streamlined approach, relying significantly on standard tenure. Evaluations in Lotte are more varied, sometimes leaning heavily on competency over achievement. Furthermore, Lotte’s human resource development strategy underscores the importance of versatility, achieved primarily through a rotation system, and adopts a top-down approach for succession planning, reflecting an institutional logic rooted in centralized decision-making. Similar findings have been noted in other studies, where decentralization and role-based rewards have been linked to greater adaptability and employee satisfaction [63].

5. Discussion

This study investigates the differences in HR practices between Samsung and Lotte, two leading South Korean conglomerates, from the perspective of the institutional logic theory [17]. By comparing their HR practices, we aim to understand how institutional logics and other contextual factors have shaped the development and divergence of HR practices in these companies [64].

We reviewed the existing literature on the institutional logic theory, which posits that organizations are influenced by the dominant logics in their institutional environments, shaping their beliefs, values, and practices [18]. We also discussed the role of globalization, technological advancements, and stakeholder expectations in shaping HR practices in organizations like Samsung and Lotte [41,65]. Furthermore, ref. [60] explores how competing institutional logics influence HR effectiveness and employee turnover, highlighting the complexity of managing HR practices in diverse institutional contexts. Additionally, ref. [26] discusses the institutional complexity of HR practices in public organizations, emphasizing the coexistence of multiple logics and their conflicting demands.

5.1. Predicting the Differentiation of HR Practices in Samsung and Lotte Using Institutional Logic Theory

The framework of institutional logic offers a unique lens through which to decipher the intricacies of organizational behavior. At its core, institutional logic hinges on the premise that organizations are shaped by the broader societal beliefs, norms, and structures within which they are embedded [56]. In analyzing Samsung and Lotte, two South Korean conglomerates, this theory provides insight into how their distinct HR practices can be understood as reflections of differing institutional logics.

Samsung’s centralized approach to HR governance, particularly in areas like job classification and recruitment procedures, suggests an institutional logic grounded in control, uniformity, and standardization. This can be seen as a strategic move to maintain consistency across its vast network of affiliates and ensure alignment with group-wide objectives. Lotte, with its decentralized governance, particularly in recruitment advertising and compensation policy determination, appears to value flexibility and subsidiary autonomy. This might be rooted in the conglomerate’s organizational structure, characterized by a myriad of smaller affiliates, where decentralized governance can foster adaptability and quick decision making [25].

Regarding job systems and role specification, Samsung’s extensive job categorization and its movement towards role-based HR strategies underscore a logic of specialization. The conglomerate seems to prioritize role clarity and adaptability, allowing individual affiliates to choose from a standardized job system. Lotte, conversely, embodies a logic of uniformity and consolidation, tailoring its job system to the characteristics of its various business units, but maintaining a strong emphasis on role-based consistency.

Samsung’s meritocratic stance in promotions, with a focus on achievement points, combined with its comprehensive evaluation structure, underscores a logic of individual meritocracy. This approach prioritizes individual accomplishments and potential. Lotte’s simpler promotion criteria and its more varied weightage in evaluations reflect an institutional logic that values tenure, role consistency, and a more collectivist approach, emphasizing cohesion within job groups [59].

In terms of recruitment and selection, while both conglomerates’ early HR practices bore Japanese influences, their recruitment and selection trajectories have diverged over time. Samsung’s emphasis on merit-based recruitment and individual performance reflects an institutional logic of adaptability and specificity. Lotte’s stronger emphasis on traditional methods, like academic background, suggests a logic valuing stability and continuity, echoing the more traditional Confucian values that underscore loyalty and long-term commitment [54].

Samsung’s meritocratic reward system, especially its use of the EVA metric, suggests a deep-rooted institutional logic that values economic value creation and individual performance. Lotte’s approach, while comprehensive, leans towards role-based consistency, reflecting an institutional logic that prioritizes cohesion and stability. In terms of HR development, Samsung’s emphasis on the “T-shaped” model suggests a prioritization of deep expertise, while Lotte’s focus on rotation systems indicates a value placed on versatility and broad industry understanding [23].

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study offers pivotal theoretical insights into the domain of HR practices, specifically focusing on South Korean conglomerates such as Samsung and Lotte. Through a comprehensive analysis rooted in the institutional logic theory, our research amplifies the understanding of the underlying factors and nuances influencing divergent HR practices.