Driving Sustainable Change: The Power of Supportive Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Fostering Environmental Responsibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

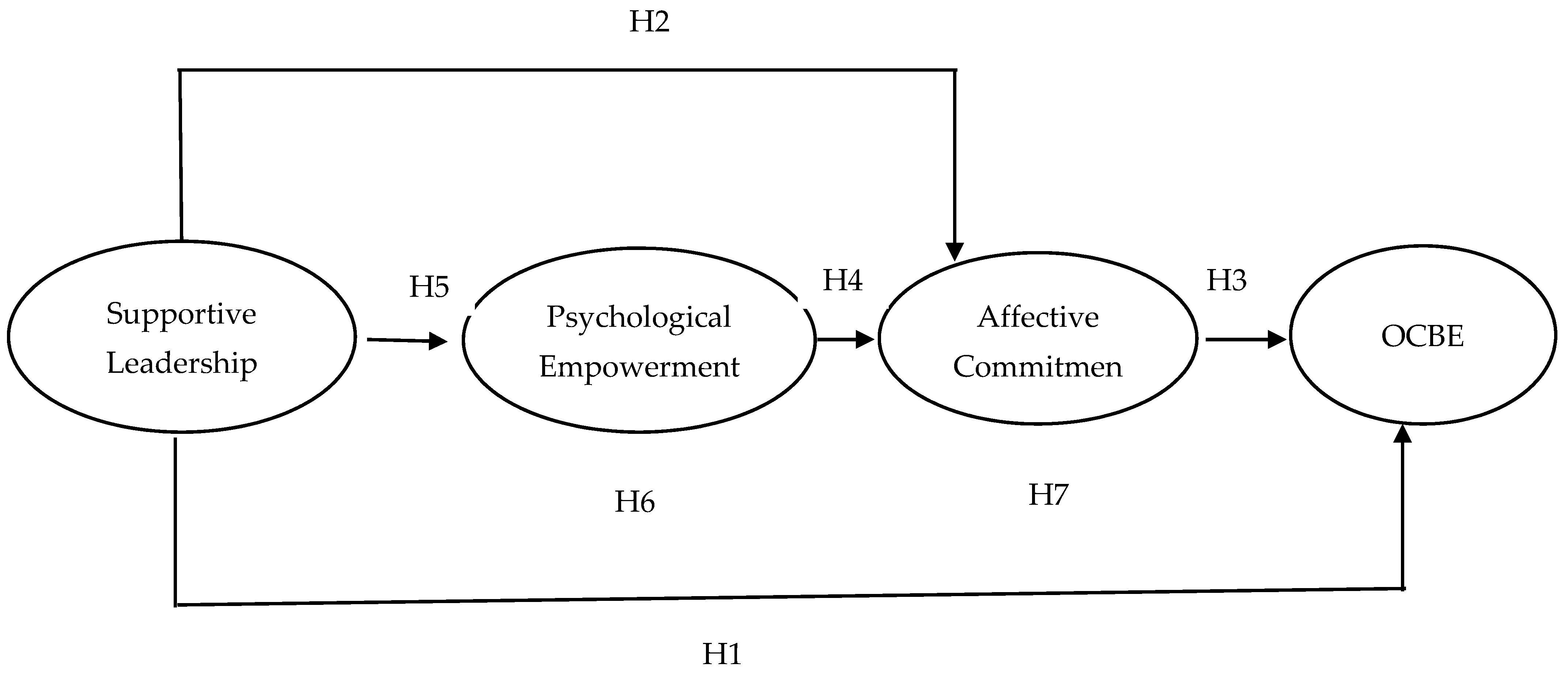

2.2. Supportive Leadership and OCBE

2.3. Supportive Leadership and Affective Commitment

2.4. Affective Commitment and OCBE

2.5. Psychological Empowerment and Affective Commitment

2.6. Supportive Leadership and Psychological Empowerment

2.7. Mediating Influence of Psychological Empowerment and Affective Commitment

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measurement Development

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

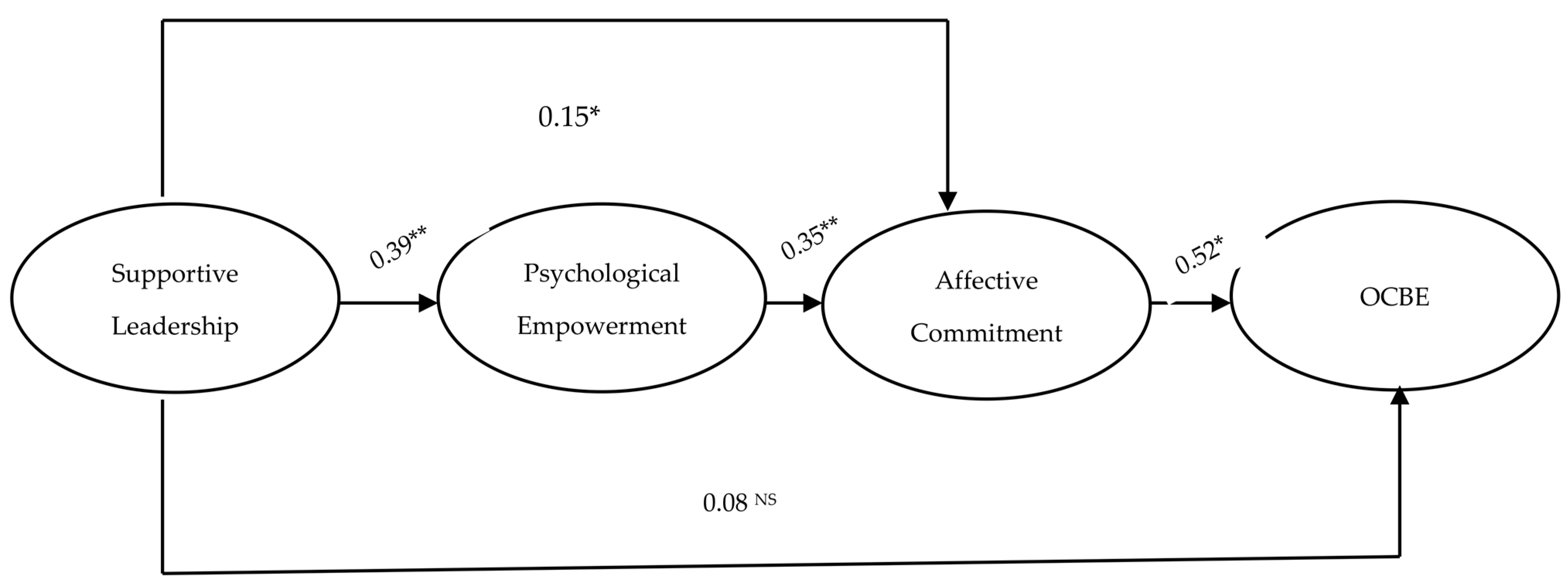

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.-C. Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsibility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galpin, T.; Lee Whittington, J. Sustainability leadership: From strategy to results. J. Bus. Strategy 2012, 33, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felin, T.; Foss, N.J.; Ployhart, R.E. The microfoundations movement in strategy and organization theory. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2015, 9, 575–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Steger, U. The roles of supervisory support behaviors and environmental policy in employee “Ecoinitiatives” at leading-edge European companies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Chen, Y. Linking environmental management practices and organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: A social exchange perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 3552–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The impact of human resource management on environmental performance: An employee-level study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temminck, E.; Mearns, K.; Fruhen, L. Motivating employees towards sustainable behaviour. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J. Ethical leadership and OCBE: The influence of prosocial motivation and self accountability. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; King, C.E. Empowering employee sustainability: Perceived organizational support toward the environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyankara, H.P.R.; Luo, F.; Saeed, A.; Nubuor, S.A.; Jayasuriya, M.P.F. How does leader’s support for environment promote organizational citizenship behaviour for environment? A multi-theory perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M.; Maak, T.; Stahl, G.K. Developing responsible global leaders through international service-learning programs: The Ulysses experience. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kura, K.M. Linking environmentally specific transformational leadership and environmental concern to green behaviour at work. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 1S–14S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Toward a new measure of organizational environmental citizenship behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Wisetsri, W.; Wu, H.; Shah, S.M.A.; Abbas, A.; Manzoor, S. Leadership styles and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The mediating role of self-efficacy and psychological ownership. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 683101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, S.; Farid, T.; Ma, J.; Khattak, A.; Nurunnabi, M. The impact of authentic leadership on organizational citizenship behaviours and the mediating role of corporate social responsibility in the banking sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.P.; Shallice, T. Hierarchical schemas and goals in the control of sequential behavior. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 113, 887–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Making Sense of the Organization, Volume 2: The Impermanent Organization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S.G. Organizational culture and individual sensemaking: A schema-based perspective. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irtaza, A.; Khan, M.M.; Sadia, S.; Mujtaba, B.G. Impact of Psychological Capital on Performance of Public Hospital Nurses: The Mediated Role of Job Embeddedness. Public Organ. Rev. 2022, 22, 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Griffin, M.A. Perceptions of organizational change: A stress and coping perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaied, M. Supportive leadership and EVB: The mediating role of employee advocacy and the moderating role of proactive personality. J. Manag. Dev. 2019, 38, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiippana, K. What is the McGurk effect? Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenberg, S.; Wesseling, H. Making sense of Weick’s organising. A philosophical exploration. Philos. Manag. 2016, 15, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mercurio, Z.A. Affective commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment: An integrative literature review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, D.; Kurian, S. Authentic leadership and performance: The mediating role of employees’ affective commitment. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.S.; Choi, B.K. A multidimensional analysis of spiritual leadership, affective commitment and employees’ creativity in South Korea. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 1035–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.; Williams, E.A. Transformational leadership, self-efficacy, group cohesiveness, commitment, and performance. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2004, 17, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Yücel, İ.; Gomes, D. How transformational leadership predicts employees’ affective commitment and performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 1901–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, P.; Krishnan, V.R. Organizational commitment of information technology professionals: Role of transformational leadership and work-related beliefs. Tec. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, T.; Akram, M.U.; Ijaz, H. Impact of transformational leadership style on affective employees’ commitment: An empirical study of banking sector in Islamabad (Pakistan). J. Commer. 2011, 3, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, S.; Omar, Z.; Ismail, I.A.; Alias, S.N.; Rami, A.A.M. Item Generation Stage: Teachers’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 29, 2503–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Podsakoff, P.M. Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122–141. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, J.; Bolino, M.C.; Kelemen, T.K. Organizational citizenship behavior in the 21st century: How might going the extra mile look different at the start of the new millennium? In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; Volume 36, pp. 51–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.J.; Yoon, H.H. Linking organizational virtuousness, engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: The moderating role of individual and organizational factors. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 879–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Furst-Holloway, S.; Masterson, S.S.; Gales, L.M.; Blume, B.D. Leader-member exchange and leader identification: Comparison and integration. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herda, D.N.; Lavelle, J.J.; Lauck, J.R.; Young, R.F.; Smith, S.M.; Li, C. Auditors’ Engagement Team Commitment and Its Effect on Team Citizenship Behavior. In Advances in Accounting Behavioral Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; Volume 25, pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansereau, F., Jr.; Graen, G.; Haga, W.J. A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the role making process. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1975, 13, 46–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, S.M.; Amin, M.; Winterton, J. Does emotional intelligence and empowering leadership affect psychological empowerment and work engagement? Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 971–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Guo, Q.; Li, J. Employee engagement, its antecedents and effects on business performance in hospitality industry: A multilevel analysis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 4631–4652. [Google Scholar]

- Grošelj, M.; Černe, M.; Penger, S.; Grah, B. Authentic and transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 677–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Otaibi, S.M.; Amin, M.; Winterton, J.; Bolt, E.E.T.; Cafferkey, K. The role of empowering leadership and psychological empowerment on nurses’ work engagement and affective commitment. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, G.; Mampilly, S.R. Relationships among perceived supervisor support, psychological empowerment and employee engagement in Indian workplaces. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2015, 30, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efiyanti, A.Y.; Ali, M.; Amin, S. Institution reinforcement of mosque in social economic empowerment of small traders community. J. Socioecon. Dev. 2021, 4, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Wu, Y.; He, Z.; Chen, Y.; Quek, T.Q.; Xu, C.-Z. Digital twin empowered mobile edge computing for intelligent vehicular lane-changing. IEEE Netw. 2021, 35, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, H.; Miettinen, M. The role of perceived development opportunities on affective organizational commitment of older and younger nurses. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2019, 49, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.A.S.; Figueiredo, K.F. Brazilian nursing professionals: Leadership to generate positive attitudes and behaviours. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2019, 32, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, A.; Robson, F. Investigation of nurses’ intention to leave: A study of a sample of UK nurses. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2016, 30, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.C.; Johnson, P.D.; Mathe, K.; Paul, J. Structural and psychological empowerment climates, performance, and the moderating role of shared felt accountability: A managerial perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso Castro, C.; Villegas Perinan, M.M.; Casillas Bueno, J.C. Transformational leadership and followers’ attitudes: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1842–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J.; Faerman, S. The role of goal specificity in the relationship between leadership and empowerment. Public Pers. Manag. 2021, 50, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, S.L. On goodness in schools: Themes of empowerment. Peabody J. Educ. 1986, 63, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.A.; Khattak, M.N.; Zolin, R.; Shah, S.Z.A. Psychological empowerment and employee attitudinal outcomes: The pivotal role of psychological capital. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewettinck, K.; Van Ameijde, M. Linking leadership empowerment behaviour to employee attitudes and behavioural intentions: Testing the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2011, 40, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farvour, J.K. The Relationship Between Supervisor Support for Student-Centered Learning Innovation, Psychological Empowerment, and Innovation Readiness Amongst Faculty at Private Four-Year Colleges; Creighton University: Omaha, NE, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Jensen, S.M. Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A. Self-efficacy and psychological ownership mediate the effects of empowering leadership on both good and bad employee behaviors. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2017, 24, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1984; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, L.; Jesus, J. Influence of total quality-based human issues on organisational commitment. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 260–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Reducing employee turnover intention through servant leadership in the restaurant context: A mediation study of affective organizational commitment. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018, 19, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Aboramadan, M.; Dahleez, K.A. Does climate for creativity mediate the impact of servant leadership on management innovation and innovative behavior in the hotel industry? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2497–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franczukowska, A.A.; Krczal, E.; Knapp, C.; Baumgartner, M. Examining ethical leadership in health care organizations and its impacts on employee work attitudes: An empirical analysis from Austria. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2021, 34, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Dhar, R.L. Factors influencing job performance of nursing staff: Mediating role of affective commitment. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Mittal, A. Meaningfulness of work and employee engagement: The role of affective commitment. Open Psychol. J. 2020, 13, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 1405–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H.; Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Griffin, M.A. Dimensions of transformational leadership: Conceptual and empirical extensions. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Paillé, P. Organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: Measurement and validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. An empirical test of a comprehensive model of intrapersonal empowerment in the workplace. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 601–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Gao, Y. Ethical leadership and work engagement: The roles of psychological empowerment and power distance orientation. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Huang, S.S.; Teo, S. Effect of empowering leadership on work engagement via psychological empowerment: Moderation of cultural orientation. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaabani, A.; Naz, F.; Magda, R.; Rudnák, I. Impact of perceived organizational support on OCB in the time of COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary: Employee engagement and affective commitment as mediators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, N.M.; Rodgers, B.; Fogarty, G.J. The relationships of experiencing workplace bullying with mental health, affective commitment, and job satisfaction: Application of the job demands control model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D. Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate data analysis. Uppersaddle River. In Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Kennesaw State University: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1998; Volume 5, pp. 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.; Kooli, C.; Alshebami, A.S.; Zeina, M.M.; Fayyad, S. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Brand Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Green-Crafting Behavior and Employee-Perceived Meaningful Work. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1097–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.A.; DeGeest, D.; Li, A. Tackling the problem of construct proliferation: A guide to assessing the discriminant validity of conceptually related constructs. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 80–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X. How responsible leadership motivates employees to engage in organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A double-mediation model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, N.; Paillé, P. Linking corporate policy and supervisory support with environmental citizenship behaviors: The role of employee environmental beliefs and commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Arasanmi, C.N.; Krishna, A. Employer branding: Perceived organisational support and employee retention–the mediating role of organisational commitment. Ind. Commer. Train. 2019, 51, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Chadee, D. Ethical leadership, self-efficacy and job satisfaction in China: The moderating role of guanxi. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, F.; O’Driscoll, M.P. Psychological ownership in small family-owned businesses: Leadership style and nonfamily-employees’ work attitudes and behaviors. Group Organ. Manag. 2011, 36, 345–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; Volume 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, B.; Naqvi, S.M.M.R.; Khan, A.K.; Arjoon, S.; Tayyeb, H.H. Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: The role of psychological safety. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecka, M.; Woosnam, K.M.; Nisbett, G.S. Self-efficacy mechanism at work: The context of environmental volunteer travel. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2002–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çekmecelioğlu, H.G.; Özbağ, G.K. Leadership and creativity: The impact of transformational leadership on individual creativity. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, D.; Lee, K.; Joshi, K. Transformational leadership and creativity: A meta-analytic review and identification of an integrated model. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 625–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Supportive Leadership | 2.56 | 0.71 | - | |||

| 2. Psychological Empowerment | 3.01 | 0.62 | 0.45 ** | - | ||

| 3. Affective Commitment | 2.84 | 0.81 | 0.27 ** | 0.23 ** | - | |

| 4. OCBE | 3.32 | 0.72 | 0.33 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.19 * | - |

| Construct | Items | Loading | A | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supportive Leadership | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.87 | ||

| SL1 | 0.916 | ||||

| SL2 | 0.861 | ||||

| SL3 | 0.807 | ||||

| Psychological Empowerment | 0.95 | 0.53 | 0.84 | ||

| PE1 | 0.772 | ||||

| PE2 | 0.839 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.933 | ||||

| PE4 | 0.953 | ||||

| PE5 | 0.824 | ||||

| PE6 | 0.727 | ||||

| PE7 | 0.929 | ||||

| PE8 | 0.923 | ||||

| PE9 | 0.813 | ||||

| PE10 | 0.738 | ||||

| PE11 | 0.823 | ||||

| PE12 | 0.706 | ||||

| Affective Commitment | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.83 | ||

| AC1 | 0.916 | ||||

| AC2 | 0.907 | ||||

| AC3 | 0.758 | ||||

| AC4 | 0.827 | ||||

| AC5 | 0.911 | ||||

| AC6 | 0.746 | ||||

| OCBE | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.73 | ||

| OCBE1 | 0.772 | ||||

| OCBE2 | 0.848 | ||||

| OCBE3 | 0.851 | ||||

| OCBE4 | 0.772 | ||||

| OCBE5 | 0.826 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-factor model (hypothesized model) | 2815.42 | 1013 | 2.779 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| 3-factor model (SL & AC combined) | 8589.54 | 1108 | 7.752 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

| 2-factor model (SL, PE & AC combined) | 9788.2 | 1166 | 8.394 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| 1-factor model | 11,974.35 | 1319 | 9.078 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| Hypotheses | Path | β Estimate | T | LLCI | ULCI | p-Value | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HI | SL→OCBE | 0.26 | 4.82 | 0.145 | 0.485 | <0.01 | (**) |

| H2 | SL→AC | 0.47 | 8.41 | 0.278 | 0.526 | <0.01 | (**) |

| H3 | AC→OCBE | 0.29 | 5.63 | 0.129 | 0.456 | <0.01 | (**) |

| H4 | PE→AC | 0.33 | 6.72 | 0.223 | 0.375 | <0.01 | (**) |

| H5 | SL→PE | 0.41 | 7.11 | 0.219 | 0.499 | <0.01 | (**) |

| Bootstrapping | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99% CI (Percentile) | 99% CI (Bias-Corrected) | ||||||||||

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | Z | Sig | LLCI | ULCI | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Direct effects SL→ | OCBE | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.14 | 0.57 | −0.09 | 0.21 | −0.11 | 0.21 | ||

| SL→ | AC | 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.5 | (**) | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | ||

| AC→ | OCBE | 0.52 | 0.06 | 8.67 | (**) | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.60 | ||

| PE→ | AC | 0.35 | 0.06 | 5.83 | (**) | 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.85 | ||

| SL→ | PE | 0.39 | 0.04 | 9.75 | (**) | 0.32 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.55 | ||

| Indirect effects SL→ | PE→ | OCBE | 0.13 | 0.046 | 2.82 | (**) | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.40 | |

| SL→ | AC→ | OCBE | 0.21 | 0.045 | 4.66 | (**) | 0.25 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.54 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jameel, A.; Ma, Z.; Liu, P.; Hussain, A.; Li, M.; Asif, M. Driving Sustainable Change: The Power of Supportive Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Fostering Environmental Responsibility. Systems 2023, 11, 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11090474

Jameel A, Ma Z, Liu P, Hussain A, Li M, Asif M. Driving Sustainable Change: The Power of Supportive Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Fostering Environmental Responsibility. Systems. 2023; 11(9):474. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11090474

Chicago/Turabian StyleJameel, Arif, Zhiqiang Ma, Peng Liu, Abid Hussain, Mingxing Li, and Muhammad Asif. 2023. "Driving Sustainable Change: The Power of Supportive Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Fostering Environmental Responsibility" Systems 11, no. 9: 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11090474

APA StyleJameel, A., Ma, Z., Liu, P., Hussain, A., Li, M., & Asif, M. (2023). Driving Sustainable Change: The Power of Supportive Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Fostering Environmental Responsibility. Systems, 11(9), 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11090474