How to Apply and Manage Critical Success Factors in Healthcare Information Systems Development? †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

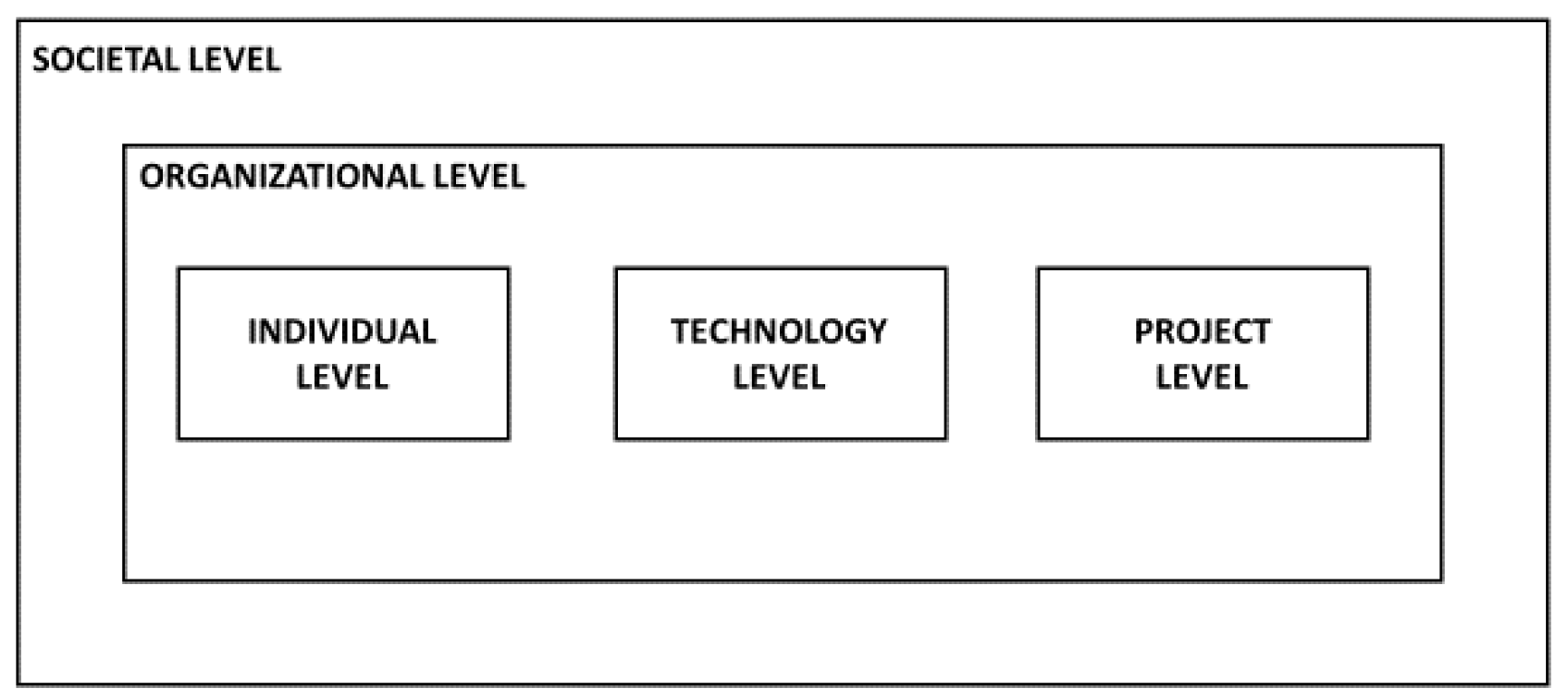

2. Research Background

- CSF1: To learn from failed projects: Organizations must learn from their own experiences and not make the same mistakes over and over again ([35,36]. This relates to Axelsson et al. (2011) [37] stating that adaptation to context is important. Also, ref. [33] highlights that a process for learning from previous mistakes should be institutionalized from the project start. Anantatmula and Rad [38] also claim that learning from past projects is critical to attaining project management maturity. It is also important to understand the earlier experiences and the organizational culture to be able to understand where important and suitable project champions can be found [39];

- CSF2: To define the system’s boundary, for the whole system and for relevant subsystems: The system’s boundary concerns the business border. It constrains what needs to be considered and what can be left outside [27]. Only if the organization as a whole is clear about its aim and works on a principle of shared values can small units be allowed to take responsibility for running themselves [40]. The system needs to fit the organizational context, and the project manager needs to be fully aware of how well the system matches the organization and its boundaries. A project is more likely to succeed if the change is limited to its boundaries, as the level of risk will be reduced [24];

- CSF3: To have a well-defined and accepted objective aligned with the business objectives: A successful IS should meet agreed-upon business objectives [35,41]. An organization should be examined from different perspectives [42] which in turn is a prerequisite for defining the objective. Commitment from management is crucial if the project affects a large part of the organization [41]. Nasri and Sahibuddin [32] define the related factor of clear and frozen requirements as critical to software projects. Already in 1983, Markus and Robey [43] stressed the importance of the organizational context for the IS. The project manager has to develop a strategy to achieve a successful implementation of the IS [29]. The business environment and both the internal and external needs of the IS need to be analyzed as a prerequisite [34];

- CSF4: To involve, motivate, and prepare the “right” stakeholders: How well an IS will work in an organization depends on the user involvement in the development process [44,45]. The success of this involvement depends on how well people work and communicate [46]. In working together as a team, it is important to adapt and tailor one’s role in the team and communicate well with each other [29]. An important IS project success factor is the ability to incorporate the views of all stakeholders in the project [31]. Moreover, cooperation among the stakeholders reduces the possible risks that may lead to project failure [34]. Furthermore, stakeholders will also act as champions (plural) for the project and it is important that they complement, not resemble, each other, and are committed to the project [39].

3. Research Method

3.1. Case Introduction

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. CSF1: To Learn from Failed Projects

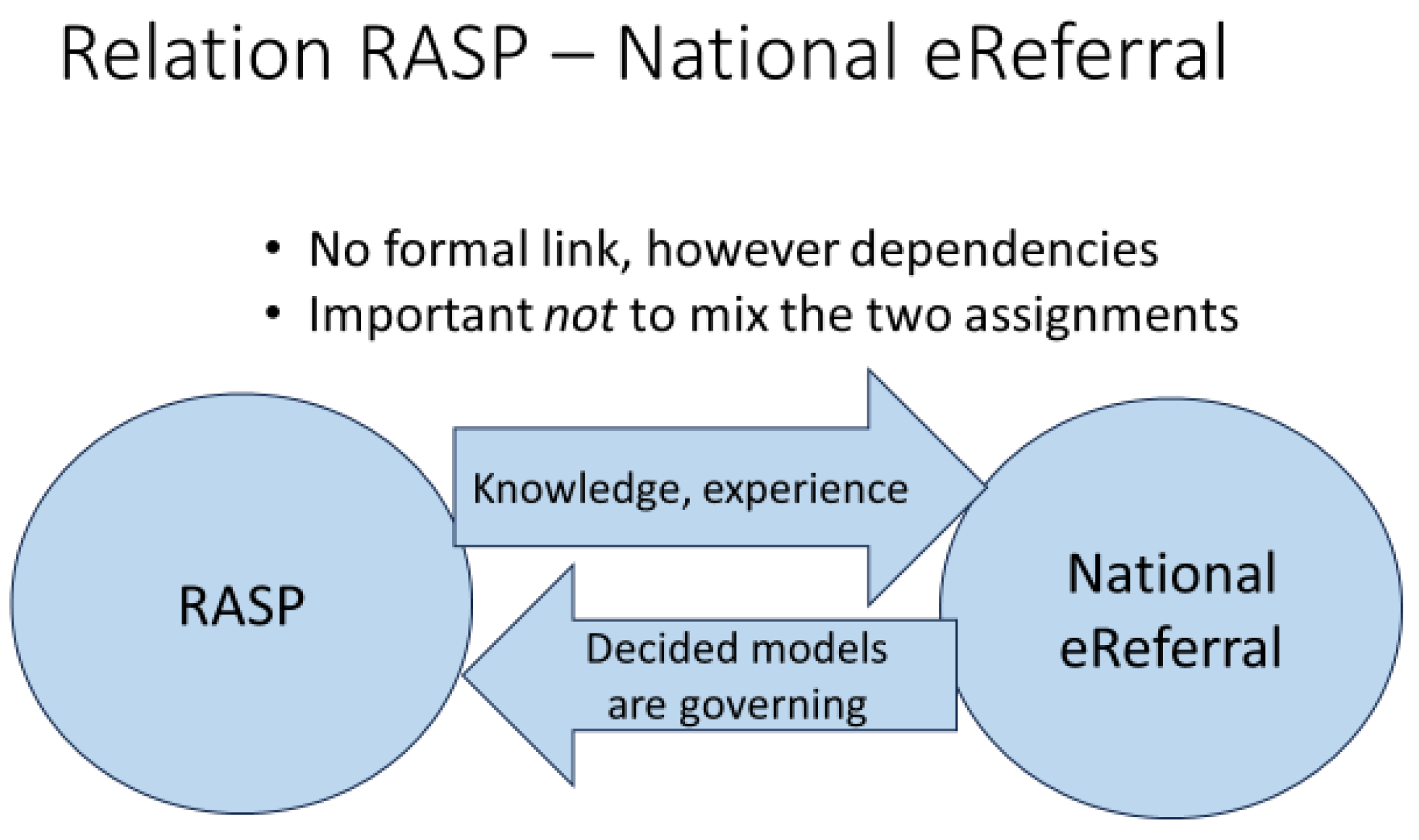

4.2. CSF2: To Define the System’s and Subsystems’ Boundaries

4.3. CSF3: To Have a Well-Defined and Accepted Objective

4.4. CSF4: To Involve the “Right” Stakeholders

5. Discussion

- Research implications: How to prospectively apply and manage CSFs on different system levels HIS development projects can now be investigated both more holistically and in more detail, at least focusing on how they interact between system levels and CSFs. Furthermore, the used CSFs are overarching and general. Thus, the results have the potential to be useful when studying CSFs in other contexts;

- Practical implications: Practitioners that address CSFs to improve their HIS projects need to be more aware of how a single CSF is implemented differently on various levels of the HIS project. The descriptions in this study can be used as practical checklists guiding how to realize situational adaptation in HIS projects. Notably, the main takeaway message may be that general CSFs need to be reformulated to more specific factors and measures on different system levels of the innovation. The tables in this paper could function as a rough checklist to raise questions such as “how do we address this CSF at the individual, technology, project and societal levels?”, forcing the project manager and the project team to be very specific, rather than assuming that the CSFs has been addressed when it has been applied at one level.

6. Conclusions

- CSFs must be managed and applied differently on various system levels;

- Interactions between different system levels have been revealed and interactions between CSFs were confirmed;

- Elaborated and refined formulations of the four CSFs were developed.

7. Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindberg, I.; Lindberg, B.; Söderberg, S. Patients’ and healthcare personnel’s experiences of health coaching with online self-management in the renewing health project. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2017, 2017, 9306192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjellebæk, C.; Svensson, A.; Bjørkquist, C.; Fladeby, N.; Grundén, K. Management challenges for future digitalization of healthcare services. Futures 2020, 24, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, S. Defining Information Systems as Work Systems: Implications for the IS Field. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2008, 17, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, D.; McDonagh, J. The Evolving Nature of Information Systems Controls in Healthcare Organisations. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R. Health information systems: Failure, success and improvisation. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2006, 75, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aanestad, M.; Vassilakopoulou, P.; Øvrelid, E. Collaborative innovation in healthcare: Boundary resources for peripheral actors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Munich, Germany, 15–18 December 2019; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- DeSanctis, G.; Poole, M.S. Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive structuration theory. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnéusson, G.; Andersson, T.; Kjellsdotter, A.; Holm, M. Using systems thinking to increase understanding of the innovation system of healthcare organisations. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2022, 36, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.S.; Thomas, M.; Baskerville, R.L. Going back to basics in design science: From the information technology artifact to the information systems artifact. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 25, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodén, J. Essentials of Information Systems; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2018; ISBN 978-91-44-12348-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, B.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Maglione, M.; Mojica, W.; Roth, E.; Shekelle, P.G. Systematic review: Impact of health information technology on quality. efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, A.; Gustavsson, L.; Svenningsson, I.; Karlsson, C.; Karlsson, T. Healthcare professionals learning when implementing a digital artefact identifying patients’ cognitive impairment. J. Workplace Learn. 2023, 35, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, H.; van Helden, K. Vicious and virtuous cycles in ERP implementation: A case study of interrelations between critical success factors. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. (EJIS) 2002, 11, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggestam, L.; Van Laere, J. How to successfully apply critical success factors in healthcare information systems development? A story from the field. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2012 20th European Conference on Information Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 10–13 June 2012; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, P.; Wagner, C. Critical success factors revisited: Success and failure cases of information systems for senior executives. Decis. Support Syst. 2001, 30, 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockart, J.F. Chief executives define their own data needs. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1979, 57, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Warren, A.M. Increasing the Value of Research: A Comparison of the Literature on Critical Success Factors for Projects, IT Projects and Enterprise Resource Planning. Systems 2016, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul, L.; Tauber, D. Critical success factors in enterprise resource planning systems: Review of the last decade. ACM Comput. Surv. 2013, 45, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameijer, B.A.; Antony, J.; Borgman, H.P.; Linderman, K. Process improvement project failure: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2022, 13, 8–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, L.; Ganvini, C.; Mendoza, L.E. Critical Success Factors Proposal to Evaluate Conditions for eHealth Services. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology & Systems, San Carlos, Costa Rica, 9–11 February 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Remus, U.; Wiener, M. A multi-method, holistic strategy for researching critical success factors in IT projects. Inf. Syst. J. 2010, 20, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, J.; Pastor, J. Organizational and technological critical success factors behavior along the erp implementation phases. In Enterprise Information Systems VI; Seruca, I., Cordeiro, J., Hammoudi, S., Felipe, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Denolf, J.M.; Trienekens, J.H.; Wognum, P.; van der Vorst, J.G.; Omta, S. Towards a framework of critical success factors for implementing supply chain information systems. Comput. Ind. 2015, 68, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrus, K.M.; Aloini, D.; Karimzadeh, S. How to Disable Mortal Loops of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Implementation: A System Dynamics Analysis. Systems 2018, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, R.L.; Carson, E.R. Dealing with Complexity, 2nd ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Avison, D.E.; Fitzgerald, G. Information Systems Development: Methodologies, Techniques and Tools, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gigch, J.P. System Design Modeling and Metamodeling; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard, I.M.; Alexander, J.A.; Hoff, T.J.; Ramanujam, R. Why does the quality of health care continue to lag? Insights from management research. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniawan, M.A.; Ashari, N.; Prastiti, R.T.; Inayah, S.; Gunawan, F.; Putra, P.H. Exploring Critical Success Factors for Enterprise Resource Planning Implementation: A Telecommunication Company Viewpoint. In Proceedings of the 2022 1st International Conference on Information System & Information Technology (ICISIT), Virtual, 27–28 July 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aggestam, L. A Framework for Preparation process In Proceedings of the 11th Doctoral Consortium in CAiSE, Riga Technical University, Riga, Lativa, 7–11 June 2004.

- Von Würtemberg, L.M.; Franke, U.; Lagerström, R.; Ericsson, E.; Lilliesköld, J. IT project success factors: An experience report. In Proceedings of the 2011 PICMET’11: Technology Management in the Energy Smart World (PICMET), Portland, OR, USA, 31 July–4 August 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, M.H.N.; Sahibuddin, S. Critical success factors for software projects: A comparative study. Sci. Res. Essays 2011, 6, 2174–2186. [Google Scholar]

- Fennelly, O.; Cunningham, C.; Grogan, L.; Cronin, H.; O’Shea, C.; Roche, M.; Lawlor, F.; O’Hare, N. Successfully implementing a national electronic health record: A rapid umbrella review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 144, 104281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaokumah, W.; Omane-Antwi, B.B.; Asante-Offei, K.O. Critical success factors of strategic information systems planning: A Delphi approach. Kybernetes 2023, 52, 1999–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewusi-Mensah, K.; Przasnyski, Z.H. Factors contributing to the abandonment of information systems development projects. J. Inf. Technol. 1994, 9, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytinen, K.; Roby, D. Learning failure in information systems development. Inf. Syst. J. 1999, 9, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, K.; Melin, U.; Söderström, F. Analyzing best practice and critical success factors in a health information system case—Are there any shortcuts to successful implementation? In Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 June 2011; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Anantatmula, V.S.; Rad, P.F. Role of organizational project management maturity factors on project success. Eng. Manag. J. 2018, 30, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laere, J.; Aggestam, L. Understanding champion behaviour in a health-care information system development project–how multiple champions and champion behaviours build a coherent whole. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. (EJIS) 2016, 25, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, H.A.; Burke, M.E. The organisation as an information system: Signpost for new investigations. East Eur. Q. 1999, 4, 549–557. [Google Scholar]

- Milis, K.; Mercken, R. Success factors regarding the implementation of ICT investment projects. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2002, 80, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, K.-F. Cultural influences on total quality management adoption in Chinese enterprise: An empirical study. Total Qual. Manag. 2001, 12, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, M.L.; Robey, D. The organisational validity of management information systems. Hum. Relat. 1983, 36, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, C.; Macredie, R.D. The Importance of Context in Information System Design: An assessment of Participatory Design. Requir. Eng. 1999, 4, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, G.J.; Ramesh, V. Improving information requirements determination: A cognitive perspective. Inf. Manag. 2002, 38, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiedian, H.; Dale, R. Requirements engineering: Making the connection between the software developer and customer. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2000, 42, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J.; White, L. A review of the recent contribution of systems thinking to operational research and management science. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 207, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Z. An evaluation of the design and construction of energy management platform for public buildings based on WSR system approach. Kybernetes 2018, 47, 1549–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, R.; Henfridsson, O.; Schultze, U. Design Principles for Competence Management Systems: A Synthesis of An Action Research Study. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 435–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, M.R.; Bartunek, J.M. Insider/Outsider Research Teams: Collaboration Across Diverse Perspectives. J. Manag. Inq. 1992, 1, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R. Reflections on Russell Ackoff’s Legacy in the Centenary Year of His Birth. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 28, 2162–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-7879-6845-5. [Google Scholar]

- Leyh, C.; Sander, P. Critical Success Factors for ERP System Implementation Projects-An Update of Literature Reviews. In Proceedings of the Enterprise Systems-Strategic, Organizational and Technological Dimensions (Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, LNBIP, St. Louis, MO, USA, 12 December 2010; Sedera, D., Gronau, N., Sumner, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 198, pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

| System Level | CSF1: to Learn from Earlier Projects, Both Successful and Failed Ones |

|---|---|

| Individual | Individuals are carriers of organizational culture and of lessons learned from earlier projects. Individual learning is the foundation for everything. Key individuals are as ambassadors crucial in communicating what has been learned, connecting to their earlier experiences, and explaining how lessons learned impact the design of the current project. To develop an individual understanding of what will be done differently this time is critical. |

| Technology | The project is redefined as a work process development project rather than a technology project, but integration of technology in the work process requires that the role of technology is addressed explicitly |

| Project | Learning from earlier projects needs to include both positive and negative experiences. It is important that lessons learned not only create understanding but also result in clear and visible alternative designs and actions in the coming project. The main differences must be communicated in a structured way. |

| Organization | Analyzing many earlier projects over time reveals organizational factors that impact development projects. The complexity of VGR required the development of a participatory structure that dealt with anchoring and creating support at all levels, departments, and roles. |

| Societal | The inertia of national standards hampered innovation and could lead to dissatisfaction with project results. Participants needed to become aware of the benefits of standards and inertia, as well as means of how the national level could be influenced in case of major issues |

| System Level | CSF2: DEFINING Boundaries and Relations |

|---|---|

| Individual | The individual project manager must understand and communicate the project’s role in the big picture. The challenge is to select individuals (project managers and members) who demonstrate the ability to clearly articulate the role of technology in the project and the contribution of the project to the larger organization. |

| Technology | The role of technology is explicitly visualized by incorporating technology as one subsystem in the larger system. Discern between information flows and work processes, as technology supports information flows. Use the swimlane technique where data stored in technological applications is one swimlane. |

| Project | From a holistic perspective, the scope of the project has to be articulated unequivocally. Boundaries of the project, and more importantly relations with and forces from the surrounding organization need to be explored, defined, and maintained over time. Map what benefits are produced for whom and clarify the project’s role in the larger whole. General CSFs need to be translated into project-specific ways of working. |

| Organization | Place the project in that organizational unit that corresponds to the aim of the project. Analyzing the organizational culture and informal decision-making processes, will also contribute to knowing what champions to involve and how to select a project manager. Analyze parallel projects, governing policies, and documents to know how they will impact the project and whether the project result is according to them, if they need to be adapted, and/or how the project can influence other projects. |

| Societal | Map how the project is related to national guidelines and other national innovation initiatives. Relations need to be actively managed, i.e., national decisions influence us but we can also influence them |

| System Level | CSF3: A Well-Defined and Accepted Objective |

|---|---|

| Individual | An accepted objective requires that each individual is involved in creating the objective so it becomes a shared objective. An emotional appeal is important and can be done by communicating the objective with examples that affect it. |

| Technology | The contribution of technology support must be explicitly connected to the overall objective. |

| Project | The project objective must be clearly linked to organizational objectives and unified stakeholder interests. Informal anchoring before formal meetings contributes to acceptance of the objective and the participative way of working. Progress towards the objective should be continuously communicated. |

| Organization | The objective needs to be accepted by all stakeholders in the different parts of the organization. Therefore, it is important to translate the general overall objective to what it actually means for different parts of the organization. It is also critical, not at least from an acceptance perspective, that the objective is formulated and communicated on a “what” level, whereas the respective departments have the freedom to fill in the “how”. |

| Societal | It is critical that the objective should not be in conflict with existing governing policies and should be in line with other strategic development projects and the overall direction for innovation. |

| System Level | CSF4: Involve the Right Stakeholders |

|---|---|

| Individual | A project needs to select and attract a number of individuals who will serve as champions for the project and will help to remove obstacles of different kinds at different levels. |

| Technology | Some of the stakeholders need to serve as a mediator that can build bridges between technological departments and business units. |

| Project | The project team members need to have different backgrounds, affiliations, and competencies that complement each other and that mirror the different stakeholder groups. The project needs an infrastructure that guides and enables interaction between the multiple identified stakeholder groups. |

| Organization | Stakeholder representatives need to cover all the different stakeholder groups and interests at different parts and levels in the organization. The commitment of all these groups needs to be managed and maintained continuously throughout the whole project. |

| Societal | In order to represent the project’s interests, both sharing knowledge developed in the project and keeping the project and the involved organizations updated, representatives from the project need to participate in other projects that have been defined as critical. |

| CSF | Origin Formulation | Elaborated Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| CSF1 | To learn from failed projects | To understand the culture and to learn from earlier projects, both successful and failed ones, and clearly communicate how these lessons learned are addressed in the current project |

| CSF2 | To define the system’s boundary, for the whole system and for relevant subsystems: | To have a holistic approach and to understand systems complexity, i.e., looking at an ISD project based on its role in the “big picture”, including defining the system’s scope and the important system elements, managing relations between system elements and relations with the environment, and paying attention to needed resources and potential risks |

| CSF3 | To have a well-defined and accepted objective aligned with the business objectives | To have well-defined and accepted objectives, on the three levels of inquiry [27], where the why level includes the top management support and the how level can be compared with having an accepted working approach and decision-making processes, as well as having an acceptance of the forthcoming result and how to test it, measure it and follow it up |

| CSF4 | To involve, motivate, and prepare the “right” stakeholders | To involve, motivate, and prepare the “right” stakeholders and develop their roles, including building the “right” team, also from champion behavior and change management perspective. This includes selecting and attracting a number of champions that will serve as sponsors for the project and will help to remove obstacles of different kinds at different levels. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aggestam, L.; van Laere, J.; Svensson, A. How to Apply and Manage Critical Success Factors in Healthcare Information Systems Development? Systems 2023, 11, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11090469

Aggestam L, van Laere J, Svensson A. How to Apply and Manage Critical Success Factors in Healthcare Information Systems Development? Systems. 2023; 11(9):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11090469

Chicago/Turabian StyleAggestam, Lena, Joeri van Laere, and Ann Svensson. 2023. "How to Apply and Manage Critical Success Factors in Healthcare Information Systems Development?" Systems 11, no. 9: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11090469

APA StyleAggestam, L., van Laere, J., & Svensson, A. (2023). How to Apply and Manage Critical Success Factors in Healthcare Information Systems Development? Systems, 11(9), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11090469