1. Background

“Wicked” problems are characterized by complexity, uncertainty, and large-scale effects and are resistant to being solved in totality by usual policy solutions [

1]. Examples of wicked problems are climate change, poverty, and waste, all of which persist despite policy interventions. Termeer and Dewulf [

2] suggest that interventions to address wicked problems are necessarily imperfect, and the aim should be to generate enough small-scale concrete and positive changes that accumulate and can lead to transformative change.

Our research team contributes social science perspectives within a publicly funded applied science institution, with a focus on maximizing beneficial impact for public good. We do this through methodological innovation with strong theoretical underpinning to address complex real-world problems. As part of ongoing work in the environmental sustainability area, the team undertook a study to explore the wicked problem of waste by looking at the effectiveness of interventions to minimize waste. A secondary objective was to test the methodological combination of realist review and system dynamics, both of them methodologies that team members had used in other contexts, such as health, but not in combination. The full waste intervention study has been published elsewhere [

3], while the secondary objective of methodological exploration is the subject of this paper.

Waste minimization interventions are defined here as those that seek to reduce waste disposed in landfills or incineration by avoiding generating waste. In contrast, waste management interventions are defined as those that seek to divert produced waste from landfill or incineration through reuse and recycling. Both waste minimization and waste management interventions attempt to create and embed change into long-term practice, where the theory of change can be explicit or implicit. Often, that theory is based on changing the behavior of individuals, even though there is clear evidence that systemic factors out of the control of individuals have considerably greater impact than individual actions alone [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

This study was a qualitative evidence synthesis that aimed to describe a theory of change for waste minimization interventions, taking systemic factors into account. The assumption was that waste has significant negative impacts on our world, and waste minimization interventions have the potential to mitigate these impacts, yet also require a lot of time, money, people, and other resources to implement [

9,

10]. Therefore, the effectiveness of waste minimization interventions, although a socially constructed concept, is a material problem in the real world. Further, the problem of waste minimization intervention effectiveness was seen as only partially knowable, and any production of a model to explain effectiveness would necessarily be imperfect. This uncertainty when dealing with a wicked problem was expected and was dealt with in part by a multimethodology approach.

Multimethodology is the process of combining different methodologies and their associated methods in one study. Multimethodology encompasses not only mixing qualitative and quantitative methods but also combinations of different qualitative methods, or different quantitative methods [

11]. The principle of multimethodology is that all methodologies give a partial understanding of the problem under investigation, and using different methodologies appropriate to the research question gives overlapping perspectives of the problem and allows a greater depth of understanding [

11,

12,

13].

The question of which methodologies can be legitimately combined, and whether the associated methods can be separated from their traditional methodologies, has been a matter of debate [

12,

14,

15]. At the core is the argument around paradigm (in)commensurability, recognizing that different methodologies are rooted in different paradigms which have different ontological, epistemological, and axiological assumptions. Some theorizing of multimethodology has employed a metamethodology, such as Habermas’ theory of communicative action, to explain and give coherence to using multiple paradigms [

12]. Pragmatism, on the other hand, disregards the problem of different paradigms and uses whatever methodologies appear to be most suited to the research questions [

11].

There appears to be a general acceptance that some form of multimethodology is useful, despite the difficulties of getting consensus around a logical coherent framework to inform the approach, as long as the assumptions around methodological choice are made explicit [

11,

12,

13]. As far as Bowers [

12] is concerned, “among the possible ways forward all but pluralism are pointless”. Multimethodology, or methodological pluralism, is a fundamental aspect of systemic intervention as developed by Midgley [

13], although he is equally concerned with defining the boundaries of the system that is the subject of the intervention. Like Ulrich [

16], Midgley believes that the emancipatory focus of critical systems approaches requires the critique of system boundaries. This combination of “boundary critique and methodological pluralism” is what Midgley [

13] sees as “the main added value of systemic intervention compared with earlier systems approaches” (p. 8). Again, the important point is that practitioners are explicit about the boundaries they are using in the intervention, as well as which discourses and whose voices are being heard.

This study of waste minimization interventions follows the principles of Midgley’s systemic intervention. The boundaries of the system of interest were deliberately set to enable a focus on more than individual behavior change and to include Māori (Indigenous) knowledges alongside Western knowledges. The multimethodology approach taken combined critical realist and qualitative system dynamics approaches, a combination suggested as complementary by some commenters [

17,

18,

19].

The objective of this paper is to discuss the benefits of this particular multimethodology combination for the design and evaluation of interventions which address wicked problems, applied here in the context of waste minimization interventions in Aotearoa New Zealand (henceforth “Aotearoa”). The next two sections introduce the two methodologies; firstly, critical realist approaches, specifically realist review methods, and secondly, causal loop diagrams and leverage point analysis from system dynamics. This is followed by a description of how these two methodologies were practically combined in this study and how the results complement each other to give greater insights into the systemic issues. This paper concludes with a reflection on this multimethodology approach.

2. Realist Review

Realist reviews have become a widely used method, especially in the health field. Realist reviews apply a realist approach to a systematic review of the literature and are “fundamentally concerned with theory development and refinement” and provide “an explanation, as opposed to a judgment of how [an intervention] works” [

20]. Realist approaches seek to explain the underlying mechanisms that interventions use to create change in a particular context, informally expressed as “what works for who, in what context” [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. By moving past description and focusing on explanation, the lessons learnt can be applied to more than one situation. At the same time, realist approaches recognize that the context of an intervention is a significant influence on the outcomes, and so the explanatory mechanism should not be separated from its context. Therefore, realist approaches use the heuristic of context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) to analyze how interventions work in practice. Realist reviews compare the CMOs from different reported interventions to develop a program theory, which is a theory of change for that context. The aim is to identify a midrange theory; one that is transferable to more than one specific local context. It is not intended to be a theory that is universally generalizable but instead remains contingent on context.

Social interventions are embedded in multiple complex systems [

13,

18]. Outcomes emerge from interactions within these systems over time. Realist approaches acknowledge the socially constructed nature of these processes, yet hold that the outcomes themselves have real and material effects in the world. A realist synthesis should include an explanation of how interventions interact with the systems in which they are embedded [

17,

19,

21]. Despite this, realist syntheses tend to focus solely on the interventions [

18]. De Souza suggests that the heuristic would be better understood as conditions–mechanisms–outcome, where “conditions” refers to the wider circumstances which are necessary for something to occur. Similarly, he suggests that the concept of “mechanism” should be broad enough to encompass causal interactions across multiple systemic levels, such as individual, community, and society. Lemire, Kwako [

21] argued for greater understanding of the concept of mechanism across different levels of embedded systems.

Dalkin and Lhussier [

17] specifically suggested Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) as a complement to realist thinking. Dalkin et al. [

17] believe that SSM is a useful tool to map the system in a way that helps stakeholders to engage with the process and refine the realist program theory. Codesign and collaborative engagement with stakeholders are important features of systemic intervention, and therefore, tools such as visual mapping which facilitate understanding of the system are important contributions to the multimethodological approach [

13].

3. System Dynamics

System dynamics is a system thinking approach which focuses on how elements fit together, interact in cause-and-effect relationships, and change over time [

26,

27,

28]. It is based on the premise that the dynamic structure of the system, described through interaction of positive and negative feedback loops, is the main determinant of the system’s behavior. The system dynamics approach is useful for visualizing interrelationships between causal factors, while keeping the structure of the whole system in view, and enabling the identification of large- and small-scale patterns through feedback loops.

With system dynamics, various qualitative (causal loop diagrams (CLDs)), quantitative (stock-and-flow diagrams), or integrated models can be created. CLDs are based on causal factors interacting within the system, which are elements that can theoretically be measured and that have some influence on the system. These are connected using system dynamics conventions to show whether their influence on other factors is positive or negative, where the chain of influence returns to the original factor in a feedback loop, and where there are time delays in the effects. Feedback loops can reinforce factors in a positive growth spiral or negative destructive spiral, or they can balance out with the effect of maintaining status quo. By analyzing the CLDs, the overall behavior of the system can be described, and unintended consequences of interventions can be predicted.

CLDs can be converted to quantitative stock-and-flow simulation models, which is a quantitative modeling step in system dynamics. These models can be run through simulation software, which can show the changing behavior of the system over time in graphical form. The approach taken in this study was to use the realist qualitative data from the literature to create a program theory and a CLD in order to visualize and analyze the waste minimization system in Aotearoa. Simulation models were not used, as they would need to be based on quantitative data and these were not generated by the realist review.

Leverage points are an analysis tool within the system dynamics approach, consisting of locations in the system where a small change in an element could create a significant shift in the system [

29,

30]. Such points are important, as by definition a system is a group of interconnected elements where the overall system behavior remains stable over time. When there are changes in the environment, a system tends to adapt so that the overall behavior remains similar. Creating sustainable change in a system is inherently difficult, and leverage points are one tool for identifying ways to effectively create change.

Donella Meadows developed a 12-level framework of leverage points [

27,

29]. Places to intervene in a system could relate to parameters (such as changing standards), feedback (such as making visible the changes created by an intervention), design (changing the rules of the system such as banning single-use plastics), and intent (such as shifting from a goal of managing waste to minimizing waste). Changing parameters and feedback is relatively simple to do and creates visible changes; however, these are known as “shallow” leverage points, as they are not very effective in creating widespread and long-lasting change in the system. Changing the design or intent of the system (deep leverage points) are harder, take longer, and involve many more people and decisions than shallow leverage points; however, they are more effective at embedding sustainable change in the system.

The focus in system dynamics on mapping causal relationships complements the realist review focus on explaining causal mechanisms. System dynamics models are understood to be constructed and partial representations of a real-world system. Similarly, realist program theories are constructed and partial representations of a real-world system. The two methodologies can offer complementary views on the same system by highlighting different features, such as the patterns of connections between CMOs for realist review or the operation of feedback loops for system dynamics. The tools taken together promote ways of supporting stakeholder engagement and deeper insights into how interventions can address wicked problems. The following section describes a practical application of this combination of methodologies in a study that examined waste minimization interventions in Aotearoa. A full report of the study has been published elsewhere [

3]. Our aim is to outline the study for the purpose of illuminating the methodological combination presented in this paper.

4. Practical Example: Waste Minimization Interventions in Aotearoa

The growing issue of waste generation, management, and disposal is a complex, wicked problem that requires a systemic approach to understand the problem and identify pathways to effective action. Waste is symptomatic of a myriad of social, economic, and environmental factors, including population growth, production, and consumption, and urban infrastructures that encroach on natural environments. The harmful effects of waste on the environment and human health continue to increase despite behavioral, technological, and policy actions for the management and minimization of waste [

9,

10]. For these reasons, while waste minimization interventions that focus only on changing individual behavior continue to be popular, as of yet, they have proven largely ineffective [

6].

Waste minimization and management in Aotearoa is the responsibility of local government authorities (councils), operating under legislation set by the central government. When faced with existing waste, local authorities must manage the immediate problem of the waste and therefore allocate resources, infrastructure, and people to waste collection, recycling, and disposal. Waste reduction strategies are often a secondary concern and, where implemented, have traditionally focused on influencing consumer behavior through information and education campaigns [

31,

32], despite research which questions the effectiveness of such individual-centered approaches [

33].

Waste interventions have been framed by the waste hierarchy—and versions of it—for many years. Early versions focused on recycling and disposal infrastructure, which tended to prioritize consumer actions. One updated hierarchy consists of “6Rs”—rethink, refuse, replace, reduce, reuse, and recycle, with disposal as a last resort [

31]. Importantly, this includes an orientation to eliminating the waste from entering the production and consumption cycles in the first place. Recent policy interventions have focused on waste minimization, such as regulating product stewardship schemes and banning single-use plastics [

31,

32]. There is also increasing integration of holistic Māori (the indigenous people of Aotearoa) worldviews into waste policies [

31,

33].

The study reported in this article sought to move away from an individual focus towards a systemic perspective on behavior change for waste minimization interventions through the combined use of realist review and qualitative causal loop diagrams. This related to the work of the social systems team within a scientific research institute, particularly in the area of sustainable development and environmental health. The motivation for the study was firstly to promote a systems approach to waste minimization, both within the research institute and the local authorities that the institute’s scientists collaborate with. Secondly, the aim was to explore methodological combinations that might result in greater insights for practical application in real-world problems. The social systems team had experience in causal loop diagramming and in realist reviews, but these had not been combined in one study. The literature suggested that such a combination could be useful for producing more nuanced insights, and therefore, the social systems team embarked on this exploratory project.

In brief, the realist review was completed first, followed by developing the CLD, and then the results from these two approaches were checked with our key informants to see that they made sense. These steps are explained in more detail in the following sections.

4.1. Realist Review Integrated Theoretical Framework

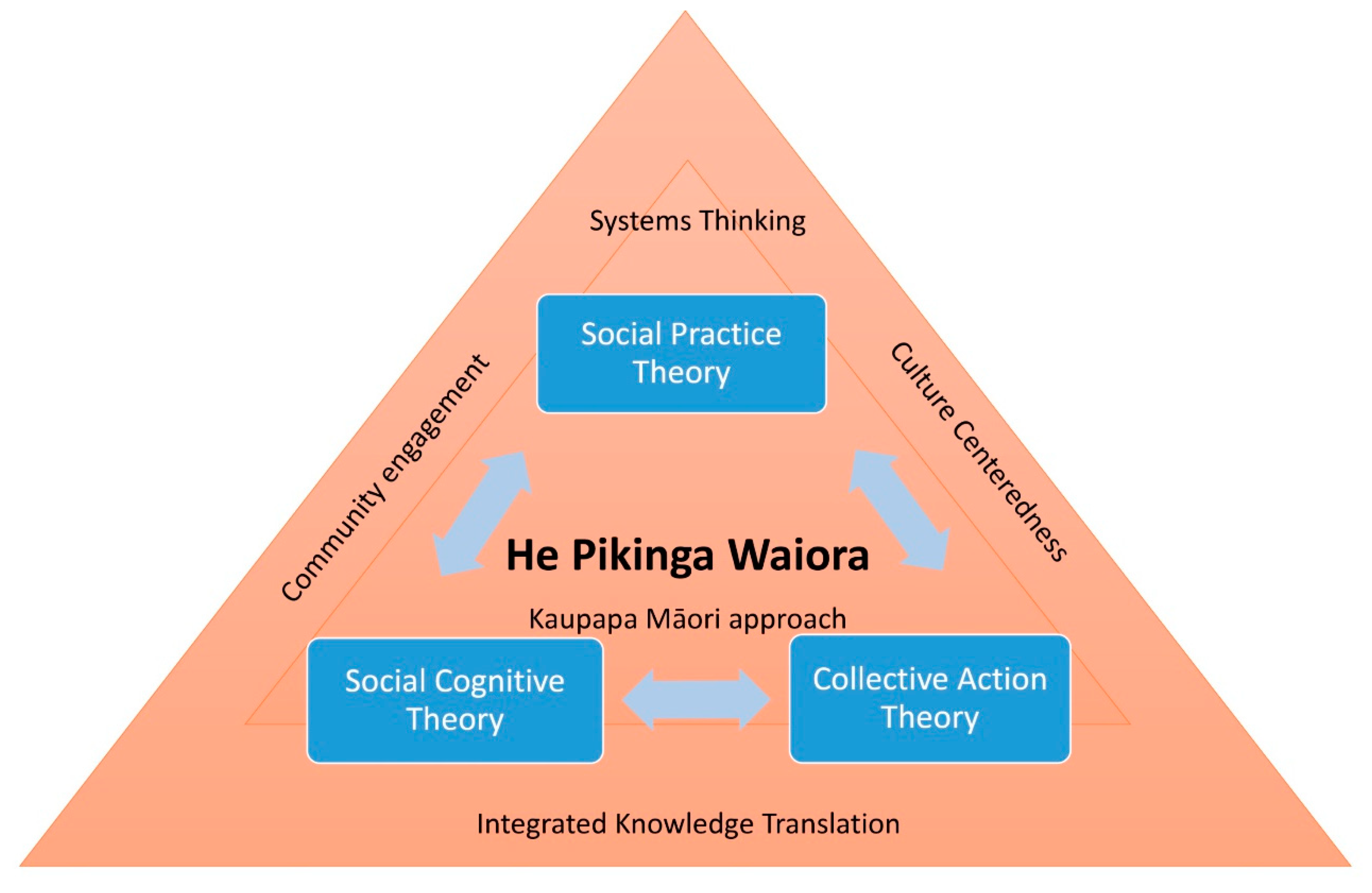

The starting point was to develop an integrated theoretical framework to guide the analysis beyond an individual focus and to ensure inclusion of Māori worldviews (

Figure 1). The framework was based on a Māori approach to evaluating implementation of interventions, named He Pikinga Waiora, which means “enhanced wellbeing” [

34,

35]. Key aspects of He Pikinga Waiora are systems thinking, community engagement, integration of Māori knowledge, and centering of Māori culture. This was used as a lens when developing the realist review program theory and the CLD. Within this overarching perspective, three key theories of change were embedded—social cognitive theory, collective action, and social practices—and the interactions between them acknowledged. Social cognitive theory recognizes environmental influences on individual behavior and seeks to create change through changing the group environment, while collective action theory focuses more on the mechanisms of cooperative behavior within a group as they tackle a social issue together. Thirdly, social practice theory emphasizes understanding everyday practices and routines on a community scale, which change across time and space. Together, these three theories create a multifaceted perspective with which to analyze the data, moving beyond the lens of individual motivation. For a more in-depth discussion of this framework, see Sharma et al. [

36].

4.2. Realist Review Program Theory

The data for the realist review came from both published literature and key informant interviews. Multiple academic databases and the Internet at large were searched for literature that discussed waste interventions in Aotearoa, including journal articles, research reports, annual reports, and policy documents. Additional efforts were made to follow leads presented in the literature to find publications from a Māori perspective, although very little was found. This process yielded 42 pieces of literature that then formed the basis for the realist review. The data were supplemented by interviews with eight key informants who had practical experience with waste interventions. These interviews were not intended to be a comprehensive survey but rather added data about practical experience of waste minimization interventions. The interviews were therefore an important addition to the data for the review. Further details about the search strategy, selection process, and interview questions are contained in the full study report [

3].

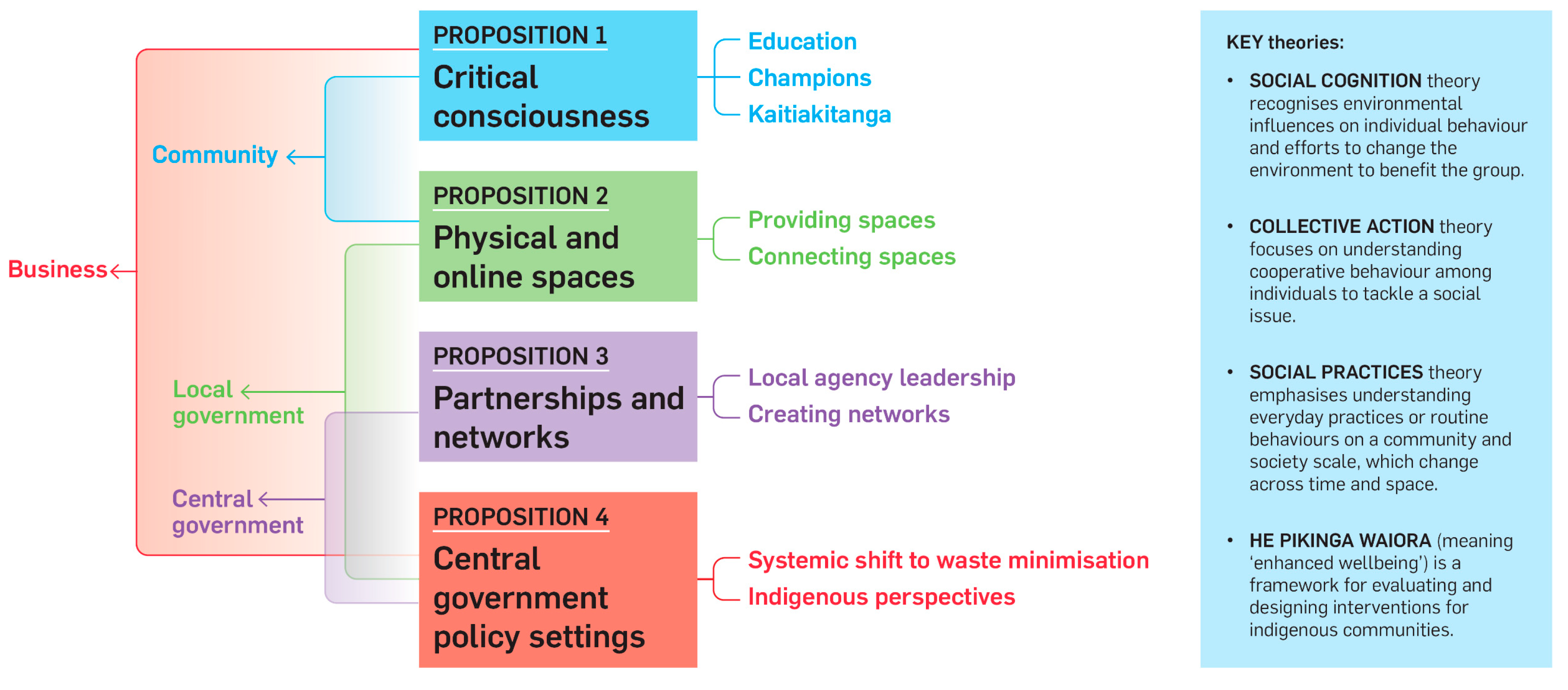

The literature and the interview transcripts were read, coded, and analyzed by the research team. For each intervention, the implicit or explicit theory of change was articulated as CMO statements. The researchers then analyzed the CMOs across the data set to look for commonalities and themes. The themes were discussed by the team to develop an overall theory that explained the data from the perspective of the integrated theoretical framework. The iterative discussions produced a generalized theory of change for waste minimization interventions that was grounded in the context of Aotearoa, in other words, a midrange program theory. The program theory was articulated as four interconnected and mutually reinforcing propositions for creating change within the waste system, as presented in

Figure 2.

The four broad propositions related to community-led interventions (propositions one and two), local government interventions (proposition three), and policy-level interventions (proposition four). All the propositions were interconnected and worked synergistically. An overview of the four propositions is given here. For a fuller discussion of the propositions, including supporting evidence taken from the literature and interviews, see Sharma et al. [

3].

Proposition One: Critical consciousness raising, concerning the need for environmental and social sustainability and kaitiakitanga (guardianship), must be part of any successful waste minimization intervention, as a shared level of knowledge is necessary to change social practices. The critical consciousness of local champions, who drive change initiatives in communities and businesses, is a key factor in effectiveness of interventions through their influence on other people.

Proposition Two: Creating physical community spaces and resources, inclusive of the range of cultures within that community, can raise critical consciousness, empower people, develop relationships, and support sustained involvement in environmental action. These spaces support and coordinate collective action, resulting in improved community wellbeing and social cohesion, as well as a shift in social practices towards waste minimization.

Proposition Three: The success of interventions is enhanced by effective partnerships between local agencies, communities, and businesses. Local government can create and encourage these partnerships through provision of services, advice, and selective resource allocation. Local government can provide leadership, role modeling the use of Indigenous worldviews and systems thinking, influence the critical consciousness of the community and businesses, and provide a supportive context for change in social practices.

Proposition Four: Shifting social practices requires the support of policies focused on waste minimization rather than waste management, which would be facilitated by policy makers who are themselves critically conscious of the need for sustainability and who apply systems thinking and indigenous knowledge principles.

In summary, these interdependent propositions relate to raising the critical consciousness of the population, providing spaces and resources to connect people, leadership from local government, and systemic change from central government. The proposed program theory assumed that to be effective, all four propositions should be implemented simultaneously and would therefore be mutually reinforcing. Further, while the propositions were located at different levels of society, that is, community, local government, and central government, the whole program theory assumed the propositions work across multiple levels, including business and industry. This finding of the importance of the multiple levels of action reinforced the suitability of using tools to depict the system in which the program theory was embedded.

The program theory was designed to be a stand-alone conceptual tool focused on explaining how change could be created that could be used on its own to inform a systemic approach for waste minimization interventions. However, in this study, the researchers added an additional step by returning to the CMO data generated from the review and visualizing the causal relationships. This was to address the intention of exploring how the two methods could be used in a complementary way. The next section outlines the causal loop diagramming work.

4.3. Causal Loop Diagram

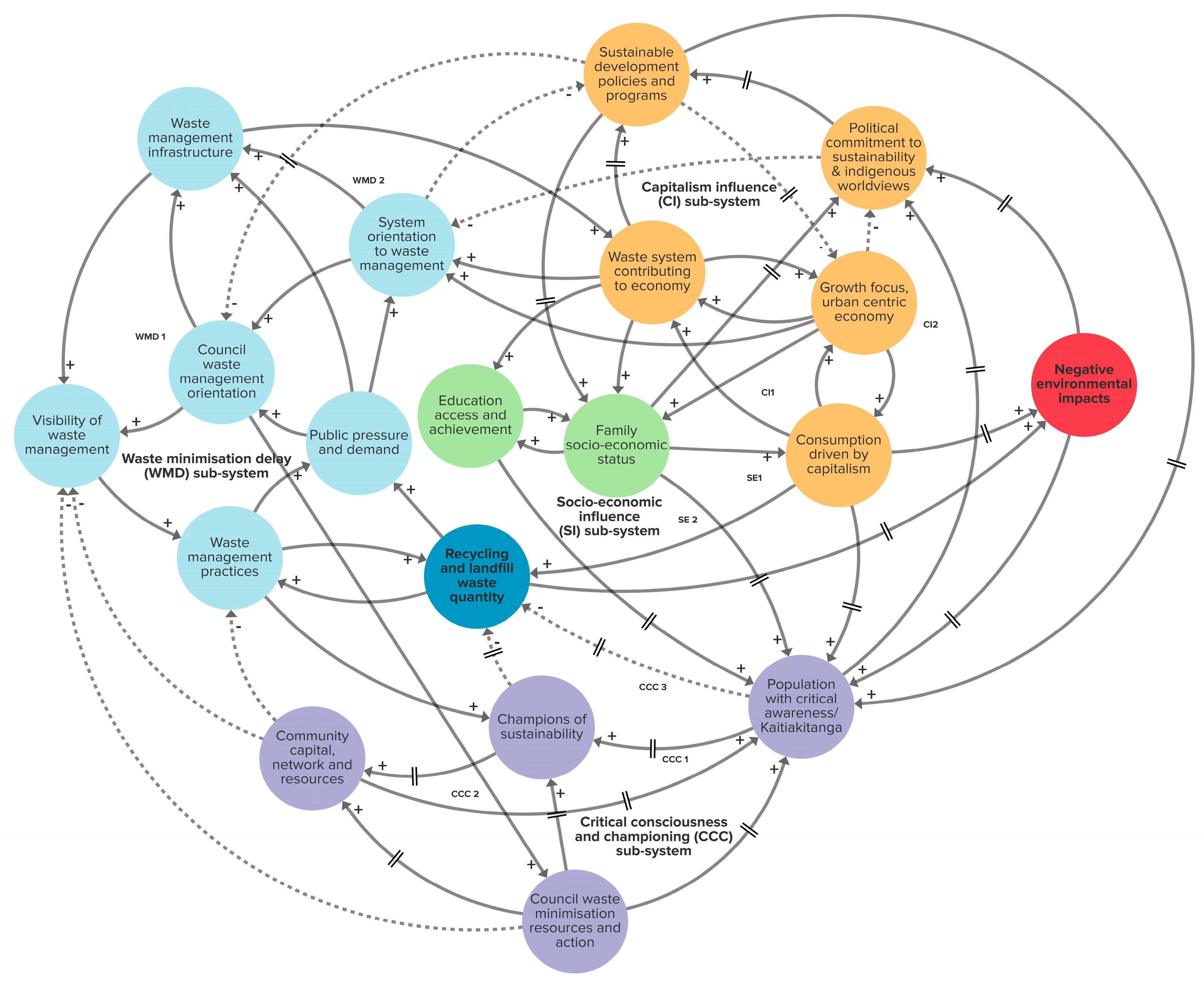

The data for the CLD were taken from the CMO analysis of the realist review and were tabulated in a spreadsheet and reanalyzed to suggest causal relationships that created change. The research team iteratively refined these proposed causal relationships, both before and after the CLD was drawn. The final agreed system CLD is shown in

Figure 3. The CLD was then examined for feedback loops, and groupings of factors that were closely interconnected and could therefore be classified as a subsystem. Four overlapping subsystems were classified, enabling the system to be considered from different perspectives: critical consciousness and championing, waste minimization delay, socioeconomic influence, and capitalism influence. The researchers acknowledge that this CLD is not fully independent of the realist review program theory, hence the similarity of CLD subsystems to the program theory propositions. The intention was to provide a different and complementary perspective to the program theory through examining causal relationships explicitly.

The critical consciousness and championing (CCC) subsystem (colored purple in the CLD) corresponded with the first and second propositions of the program theory, that is, actions related to individuals and their environment. It highlighted the importance of champions of waste minimization in the community due to their role in increasing the critical consciousness of the general population. This increase in critical consciousness leads to greater local and national political pressure to decrease waste, a greater awareness of the contribution that Māori worldviews can make to sustainable social practices, and ultimately, a reduction in waste. However, these loops have delayed effects, so there is difficulty in maintaining the political pressure in the absence of visible impacts. Impacts on climate change, for example, will take decades to be seen.

The waste minimization delay (WMD) subsystem (colored blue) related to proposition three, concerning action at a local level by local councils and businesses. It showed the reinforcing nature of the waste management system, which acts quickly to remove waste from the public domain but does not reduce the amount of waste being produced. There is public pressure for this system to continue, and resources are therefore allocated to waste disposal and recycling and not to prevention and waste minimization initiatives. It is a feedback loop that dominates the waste system and is hard to alter.

The socioeconomic influences (SE) subsystem (colored green) related to all the program theory propositions, highlighting the fact that our system is geared towards consumerism, making it cheaper to replace than reuse. It also highlighted that the waste management economy significantly contributes to the socioeconomic status of communities, for example, through employment. On the contrary, waste minimization costs individuals time, effort, and money, and this is more difficult for those who work long hours and/or have low incomes.

The final subsystem was capitalism influences (CI) (colored orange), and it connected with proposition four of the program theory, operating at a political level. Capitalism was shown to be a driving force in the system, and it is so embedded that it would be extremely hard to shift. The central capitalist effort towards continual growth of the economy resulted in consumerism, production of waste, and the allocation of resources to short-term growth initiatives rather than a long-term sustainability focus. The Māori perspective of intergenerational sustainability was overridden by the dominant capitalist subsystem.

Overall, the CLD showed a dominance of feedback loops which reinforced managing waste through processes such as recycling and disposal. This meant resources would be targeted to waste management with little left over to pursue waste minimization strategies, despite the long-term benefits of waste minimization. Attempts to shift the system towards waste minimization would be counteracted by capitalist and socioeconomic influences, therefore maintaining the status quo. To find ways of shifting the waste system for a more sustainable future, a leverage point analysis was carried out, as described in the next section.

4.4. Leverage Point Analysis

Leverage points are places in a system where a small shift in one variable could produce significant changes in the system [

27,

29]. As described in the system dynamics section earlier, leverage points can be thought of on a continuum from “shallow” changes, which are easy to do but create minimal change, through to “deep” changes, which are difficult to achieve but have the potential to create long-lasting system change. The whole CLD, along with program theory, were examined by the research team and iteratively analyzed to identify a combination of leverage points for effective waste minimization.

Three key points were identified where interventions might be focused to shift the system away from waste management and towards waste minimization. One key intervention was to increase the number of individuals in the population who are critically aware of the need for change. Critical consciousness is arguably a pivotal element in all social change and forms the basis of proposition one and two in the program theory, as well as the critical consciousness and championing subsystem. This concept refers to an individual’s mindset, where people are aware of systemic inequities and therefore take steps to resist the norms and processes that produce these inequities [

37,

38]. Although this awareness does not always result in action on an individual level, the larger the mass of people who are critically conscious of the need for change, the greater the possibility of change occurring. The “mindset” of people is a deep leverage point and has the potential to create a significant shift in the system [

27,

29].

The second key point for intervention relates to the interconnections between limited resources for waste initiatives and the highly visible and politically appealing nature of waste disposal and recycling strategies. These are some of the reasons that proposition three of the program theory requires the support of community and central government (propositions one, two, and four) to be effective. The whole waste system needs to be redesigned for waste minimization to be achieved. The waste system redesign could use economic policy levers to counteract the capitalism influences subsystem shown in the CLD. Everyone should share the costs of waste, just as everyone shares the negative environmental impacts, acting as a change incentive within a capitalist economic system. This is a “rules” change, which Meadows’ framework suggests is a “deep” level, and therefore is likely to lead to effective systemic change.

The CLD also highlighted that the paradigm of continual growth creates a consumerist society where “more is better”, and the byproduct is increasing waste, with subsequent negative impacts on the environment. This is the third key point for intervention. Raising population critical consciousness and redesigning the waste system will only have a limited effect unless this paradigm is changed. Conversely, changing the paradigm, one of Meadow’s deepest leverage points, has the potential to significantly shift the waste system towards minimization. There is growing support for normalizing alternatives to a growth-focused paradigm at both a community and policymaking level [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Further, shifts to regenerative and redistributive economies are well supported in Mātauranga Māori (indigenous Māori knowledge) [

39,

41]. Greater understanding and widespread use of the Māori concept of kaitiakitanga, based on intergenerational and reciprocal responsibilities to care for the environment which nurtures us, would support such a paradigm shift.

4.5. Feedback from Key Informants

As the realist program theory and the CLD both represent constructed models of the waste system, we checked the models with our key informants to ensure that these models made sense to them. While an in-person workshop was originally planned for this exercise, due to COVID-19 restrictions, asynchronous online tools were used for feedback instead. This was in the form of a Kumu (online interactive system mapping software) presentation that gave a summary of the findings, including presenting the integrated theoretical framework, the refined program theory, and the CLD. The software application allowed stakeholders to investigate the CLD on their own time (see

https://esr.kumu.io/beyond-behaviour-change-project). This was followed with a Qualtrics survey to get feedback on the presentation. We found that there was little feedback through these formal mechanisms, yet in later conversations, our key informants told us that they enjoyed and appreciated the opportunity to look at the findings in this way. They said they found the CLD a little complex and did not feel qualified to comment on it. This feedback was used to simplify some of the wording on the CLD, and the researchers also produced a much-simplified version for public use that showed the basic overall structure.

5. Discussion

This article reports on a methodological combination of realist review and qualitative causal loop diagramming. This was shown to be effective in informing the design principles of interventions with a systemic approach. In this section, we discuss and reflect on the methodological learnings from the case study of waste minimization interventions in Aotearoa.

As the same qualitative data were used to generate both the realist review program theory and the CLD, they were complementary ways of understanding the system, and together added a more complex and nuanced understanding of the system than either method alone. The realist review explained the mechanisms, whereas the CLD visualized the complexity by showing feedback interactions and delays. For example, the effects of sustainability champions at the community level on raising the critical consciousness of the public was noted in both approaches, with the CLD additionally showing the importance of reaching a sufficient mass of critical consciousness to have significant impact. Further, the need for dedicated spaces and places for community work was highlighted in the program theory as an individual proposition and was then shown in context in the CLD as part of the delayed critical consciousness loop. Another theme was leadership, which was noted as significant in both approaches, with the program theory additionally showing how this occurs at each of the levels and including the idea of partnerships to create change. Both approaches clearly showed that waste management (including recycling) dominates resource use at the expense of waste minimization initiatives, and that if this does not change, the system will not shift in any significant way. However, each approach gave a different perspective on this insight and showed it in a different way. These similarities and differences between findings from the two different methodologies support the idea of complementarity between them.

The publication of the protocol was a useful first step for the exploration, enabling a robust preparation for the realist review [

36]. Careful attention to protocol development is considered good practice in qualitative research [

23,

43,

44]. One benefit of the team process of developing the protocol for this study was the ability to distinguish between essential methods and those that could be adapted, allowing flexibility when circumstances change, such as the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic or inclusion of the system dynamics method to complement the realist review. Due to COVID-19, this study was adapted from the face-to-face participant workshop to an online format to achieve the primary purpose of engaging stakeholders in a sense-making exercise. Although this resulted in less participant engagement than we might have expected from a face-to-face workshop, the asynchronous online format had some benefits. The participants’ feedback was that they enjoyed the ability to progress through the presentation at their own pace and explore the diagram using the interactive features. The research team therefore agrees with other researchers who see the potential for such online tools in collaborative research [

45,

46,

47]. They offer a cost-effective and efficient means of collaboration, which is likely to be more effective in the future as people become increasingly familiar with online tools.

We also acknowledge that variations in the steps of the protocol can result in different findings. In this case, the realist review with the associated program theory was completed first. The qualitative data from that process, which included the literature, the interviews, and the program theory, were all used to develop the CLD. Therefore, the program theory and the CLD cannot be considered as independent, but rather, they are different views of the same system model. Alternatively, we could have started with the key informants in a group model building exercise [

48], where the causal factors used in the CLD came directly from the group and the structure of the CLD was agreed on by the group as a first step. The second step would then have been to use the literature in a realist review approach to develop a program theory, and the final step would be to compare the two. The goal of this process would not be to present one comprehensive model that explained the waste system in Aotearoa; rather, it would be to examine the two approaches to see what insights could be gained through looking for similarities and differences.

In the context of Aotearoa, Indigenous Māori communities are often marginalized in research collaborations [

49], and therefore, this study deliberately took a critical systems focus in the emancipatory sense [

12] to ensure that voices of Māori were a significant part of this study. The intention was to center Māori knowledges as much as possible; however, precisely because of historical marginalization, the pool of existing literature is limited, and Māori expertise is overburdened. Further work to integrate Māori knowledges and worldviews would strengthen both program theory and the CLD. Furthermore, in general, the inclusion of Indigenous knowledges has the potential for increasing research impact [

50,

51]. This is more evidence that a systemic approach to countering discrimination and the effect of colonization is needed.