The Role of Privacy Obstacles in Privacy Paradox: A System Dynamics Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Social Media Uses and Gratifications

3. Privacy

3.1. Informational Privacy

3.2. Privacy Paradox

3.2.1. Privacy Calculus

3.2.2. Incomplete Information, Bounded Rationality, and Decision Biases

- The affect bias: People tend to judge and make decisions quickly based on their current emotions, thereby underestimating the risks of things they like and overestimating the risks of things they dislike [54].

- The availability bias: People tend to overestimate and rely on information they can easily recall, because it might be present in the media, rather than information that is relevant [55].

- The confirmation bias: People tend to search for, interpret, favour, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports their beliefs or values [56].

- The hyperbolic discounting/immediate gratification bias: People tend to forego more rewarding future benefits in order to obtain less rewarding immediate benefits [57].

- The optimism bias: People tend to overestimate the likelihood of experiencing positive events and underestimate the likelihood of experiencing negative events compared to others [58].

3.2.3. Social Influence

3.2.4. Privacy Paradox in Social Media

3.2.5. Summary of Privacy Paradox Explanations

3.3. Privacy Obstacles

Relation of Privacy Paradox Explanations to Privacy Obstacles

4. System Dynamics Modelling

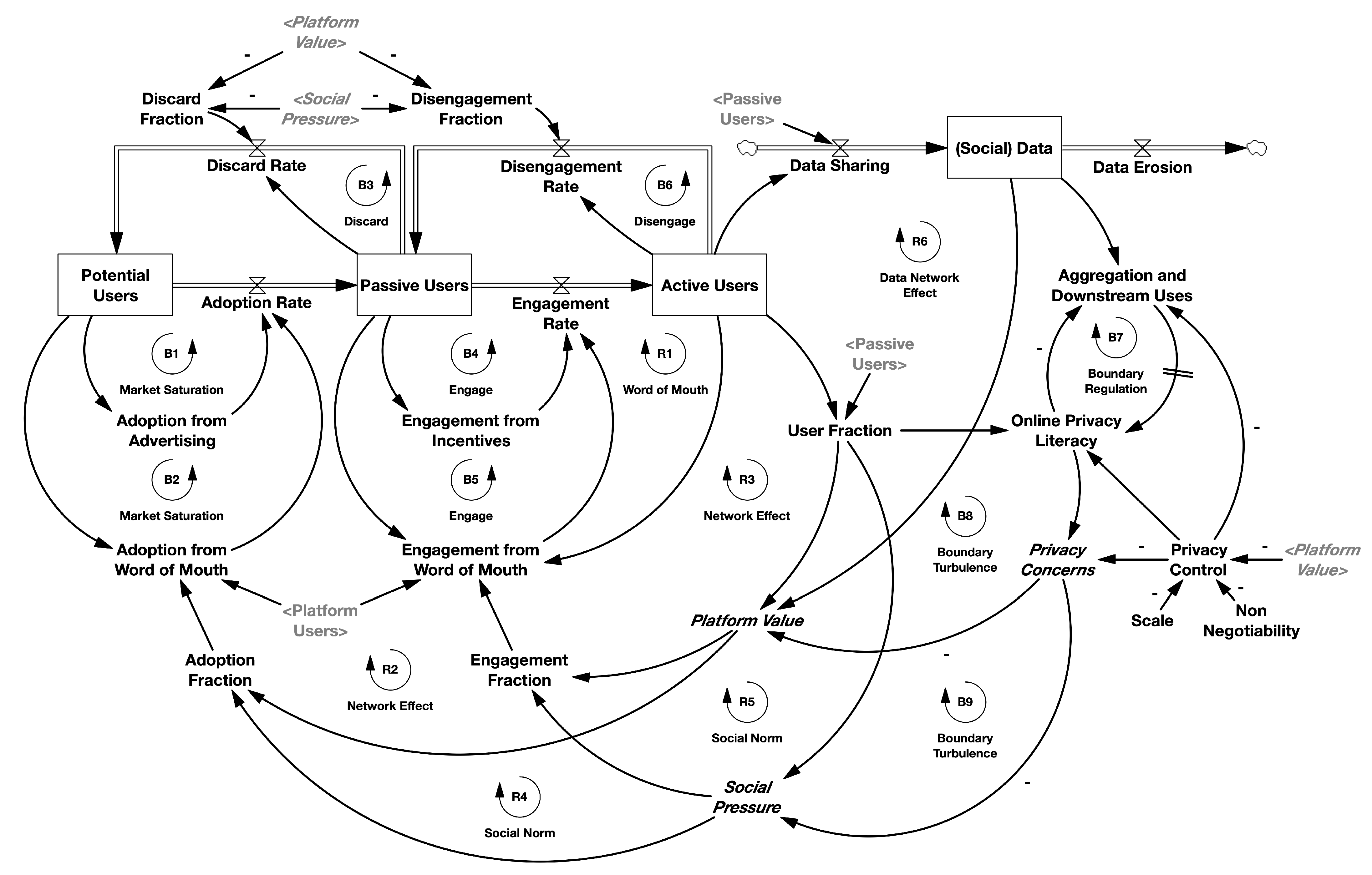

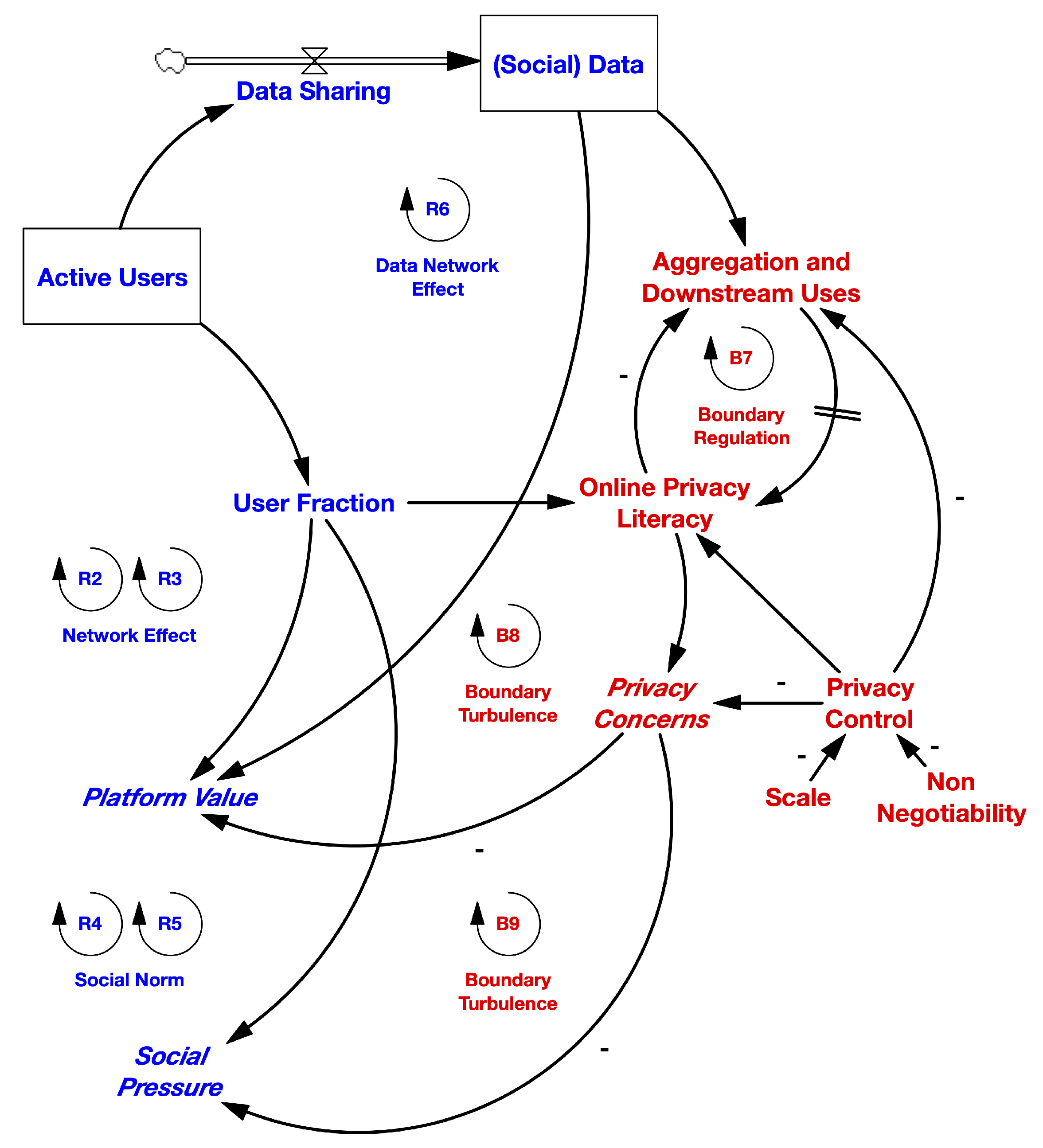

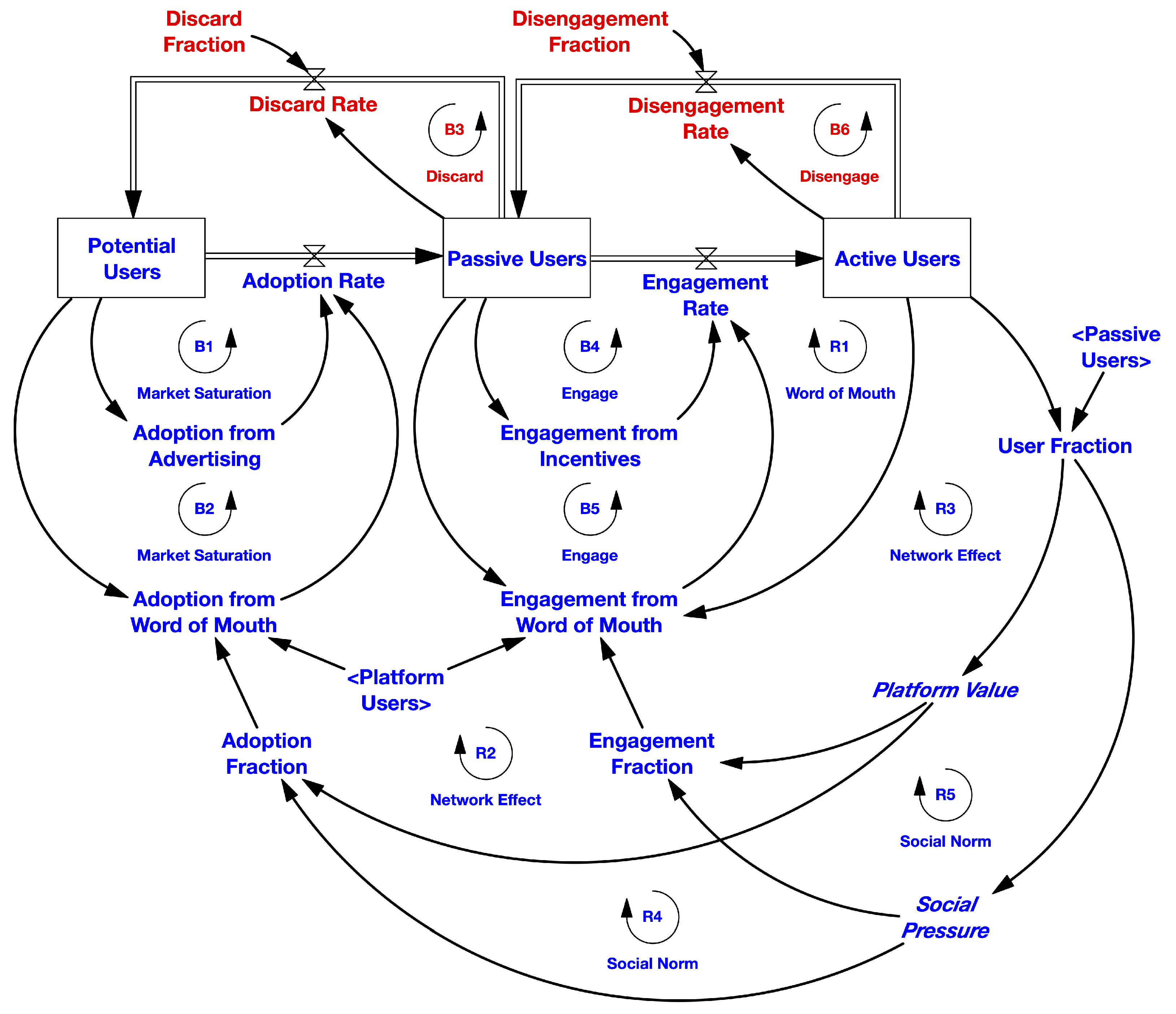

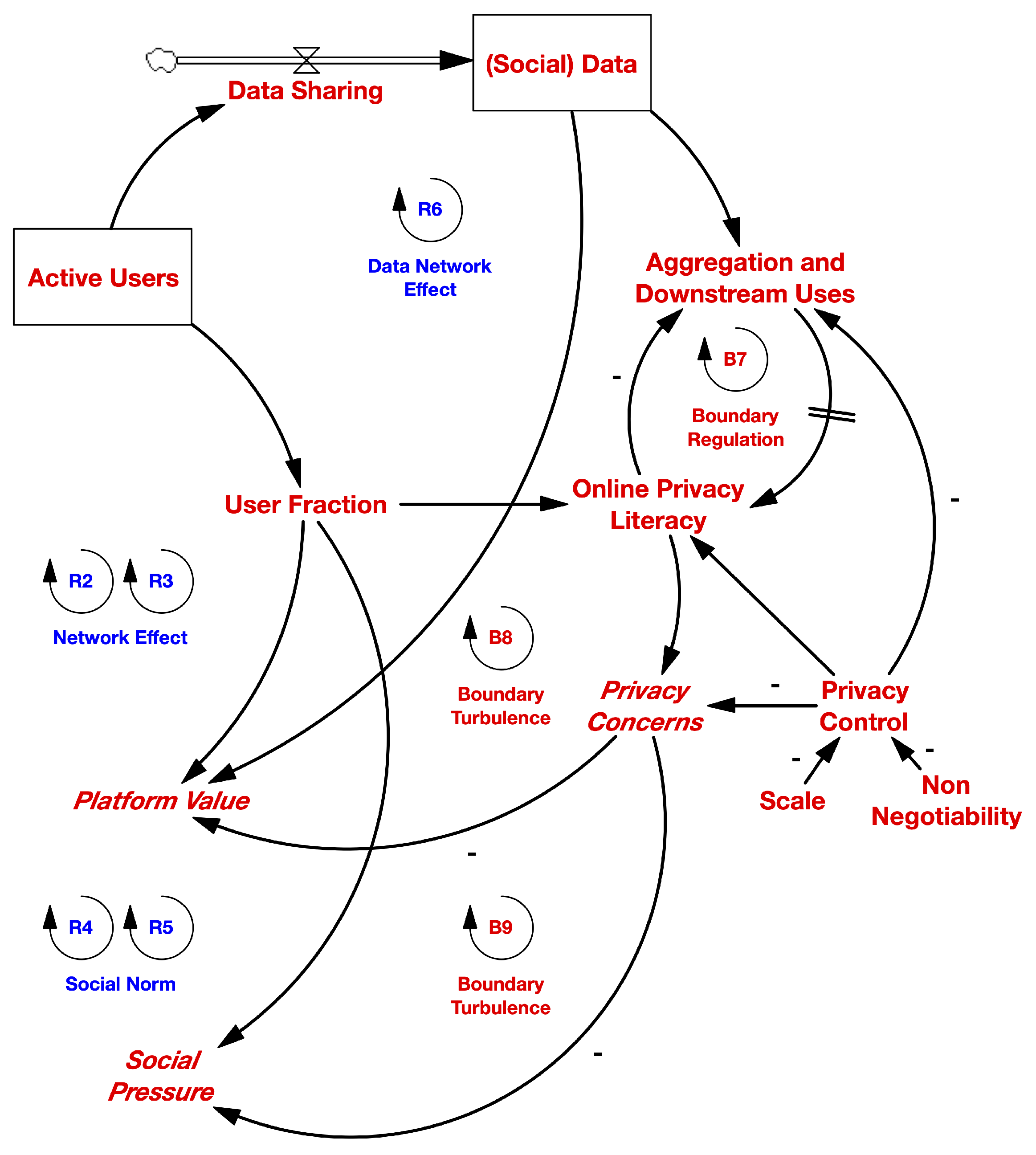

5. Dynamic Model of Interdependencies between Privacy Obstacles and Social Media Adoption and Use

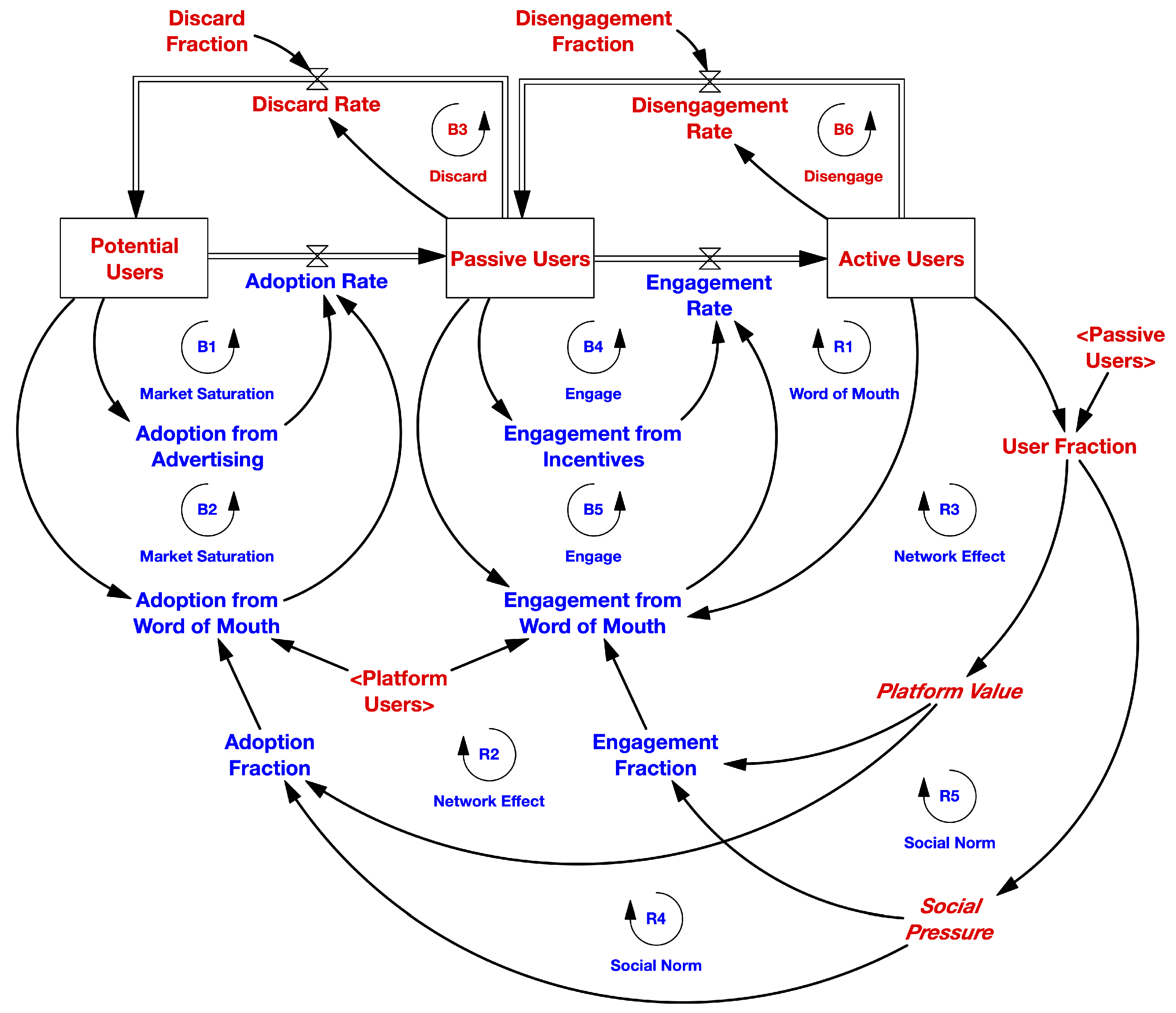

5.1. Feedback Loops

5.2. Effect of Privacy Obstacles on Feedback Loops

5.3. Model Testing and Validation

6. Analysis

7. Discussion

7.1. Towards Informed Cost-Benefit Analysis

7.2. Towards Rational Cost-Benefit Analysis

7.3. Towards Thorough Cost-Benefit Analysis

7.4. Studying Privacy with System Dynamics

7.5. Directions for Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Dijck, J. Facebook and the Engineering of Connectivity: A Multi-Layered Approach to Social Media Platforms. Convergence 2013, 19, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijck, J. ’You Have One Identity’: Performing the Self on Facebook and LinkedIn. Media Cult. Soc. 2013, 35, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuboff, S. Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization. J. Inf. Technol. 2015, 30, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.M. Data Capitalism: Redefining the Logics of Surveillance and Privacy. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, B.; Malgieri, G. Priceless Data: Why the EU Fundamental Right to Data Protection Is at Odds with Trade in Personal Data. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2022, 45, 105683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rughiniș, R.; Rughiniș, C.; Vulpe, S.N.; Rosner, D. From Social Netizens to Data Citizens: Variations of GDPR Awareness in 28 European Countries. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2021, 42, 105585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Online Privacy and Data Protection in the European Union (EU). 2016. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/38093/online-privacy-and-data-protection-in-the-european-union-eu-statista-dossier/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Statista. Online Privacy in the United States. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/17352/online-privacy-statista-dossier/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Brown, B. Studying the Internet Experience; HP Laboratories Technical Report 49; Hewlett-Packard Company: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, P.A.; Horne, D.R.; Horne, D.A. The Privacy Paradox: Personal Information Disclosure Intentions versus Behaviors. J. Consum. Aff. 2007, 41, 100–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, S.; de Jong, M.D.T. The Privacy Paradox—Investigating Discrepancies Between Expressed Privacy Concerns and Actual Online Behavior—A Systematic Literature Review. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1038–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokolakis, S. Privacy Attitudes and Privacy Behaviour: A Review of Current Research on the Privacy Paradox Phenomenon. Comput. Secur. 2017, 64, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, N.; Gerber, P.; Volkamer, M. Explaining the Privacy Paradox: A Systematic Review of Literature Investigating Privacy Attitude and Behavior. Comput. Secur. 2018, 77, 226–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtiniemi, T.; Kortesniemi, Y. Can the Obstacles to Privacy Self-Management Be Overcome? Exploring the Consent Intermediary Approach. Big Data Soc. 2017, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, L. How to Boil a Live Frog. Analysis 2000, 60, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzeta, C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N. Motivations to Use Different Social Media Types and Their Impact on Consumers’ Online Brand-Related Activities (COBRAs). J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 52, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Haas, H.; Gurevitch, M. On the Use of the Mass Media for Important Things. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1973, 38, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and Gratifications Research. Public Opin. Q. 1973, 37, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuail, D. Mass Communication Theory: An Introduction; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Muntinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mull, I.R.; Lee, S.E. “PIN” Pointing the Motivational Dimensions Behind Pinterest. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 33, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Kim, J.J. Gratifications of Using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat to Follow Brands: The Moderating Effect of Social Comparison, Trust, Tie Strength, and Network Homophily on Brand Identification, Brand Engagement, Brand Commitment, and Membership Intention. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.; Rauschnabel, P.A.; Antony, M.G.; Car, S. A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Croatian and American Social Network Sites: Exploring Cultural Differences in Motives for Instagram Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Why Do People Watch Others Play Video Games? An Empirical Study on the Motivations of Twitch Users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumter, S.R.; Vandenbosch, L.; Ligtenberg, L. Love Me Tinder: Untangling Emerging Adults’ Motivations for Using the Dating Application Tinder. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Reich, B. Social Media and Loneliness: Why an Instagram Picture May Be Worth More Than a Thousand Twitter Words. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Fioravanti, G. Why Narcissists Are at Risk for Developing Facebook Addiction: The Need to Be Admired and the Need to Belong. Addict. Behav. 2018, 76, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.; Bryant, K. Instagram: Motives for Its Use and Relationship to Narcissism and Contextual Age. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.L. Social Media Engagement: What Motivates User Participation and Consumption on YouTube? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Hsu, C.L.; Chen, M.F.; Fang, C.H. New Gratifications for Social Word-of-Mouth Spread via Mobile SNSs: Uses and Gratifications Approach with a Perspective of Media Technology. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Kumar, A. Variations in Consumers’ Use of Brand Online Social Networking: A Uses and Gratifications Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. Generational Differences in Content Generation in Social Media: The Roles of the Gratifications Sought and of Narcissism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chang, S.L. User-Orientated Perspective of Social Media Used by Campaigns. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erz, A.; Marder, B.; Osadchaya, E. Hashtags: Motivational Drivers, Their Use, and Differences Between Influencers and Followers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiner, D.J.; Kobilke, L.; Rueß, C.; Brosius, H.B. Functional Domains of Social Media Platforms: Structuring the Uses of Facebook to Better Understand Its Gratifications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 83, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepte, S.; Scharkow, M.; Dienlin, T. The Privacy Calculus Contextualized: The Influence of Affordances. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, A.; Mubarak, S.; Raymond Choo, K.K. Information Privacy in Online Social Networks: Uses and Gratification Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, R.S. The Social Impact of Computers; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holvast, J. Vulnerability and Privacy: Are We on the Way to a Risk-Free Society? Facing Chall. Risk Vulnerability Inf. Soc. 1993, 33, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Westin, A.F. Privacy and Freedom; Atheneum: Berlin, Germany, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I. The Environment and Social Behavior: Privacy, Personal Space, Territory, and Crowding; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I. Privacy Regulation: Culturally Universal or Culturally Specific? J. Soc. Issues 1977, 33, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronio, S. Boundaries of Privacy: Dialectics of Disclosure; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Westin, A.F. Social and Political Dimensions of Privacy. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzoglou, E.; Kortesniemi, Y.; Ruutu, S.; Elo, T. Privacy Paradox in Social Media: A System Dynamics Analysis. In Computational Science—ICCS 2022; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Groen, D., de Mulatier, C., Paszynski, M., Dongarra, J.J., Sloot, P.M.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13350, pp. 651–666. [Google Scholar]

- Culnan, M.J.; Armstrong, P.K. Information Privacy Concerns, Procedural Fairness, and Impersonal Trust: An Empirical Investigation. Organ. Sci. 1999, 10, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solove, D. Privacy Self-Management and the Consent Dilemma. Harv. Law Rev. 2013, 126, 1880–1903. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquisti, A.; Grossklags, J. Privacy and Rationality in Individual Decision Making. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2005, 3, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquisti, A.; Grossklags, J. What Can Behavioral Economics Teach Us About Privacy? In Digital Privacy: Theory, Technologies, and Practices; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Flender, C.; Müller, G. Type Indeterminacy in Privacy Decisions: The Privacy Paradox Revisited. In Quantum Interaction—QI 2012; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Busemeyer, J.R., Dubois, F., Lambert-Mogiliansky, A., Melucci, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7620, pp. 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. Models of Bounded Rationality, Volume 1: Economic Analysis and Public Policy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. The Affect Heuristic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 177, 1333–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Bless, H.; Strack, F.; Klumpp, G.; Rittenauer-Schatka, H.; Simons, A. Ease of Retrieval as Information: Another Look at the Availability Heuristic. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plous, S. The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Acquisti, A.; Grossklags, J. Losses, Gains, and Hyperbolic Discounting: An Experimental Approach to Information Security Attitudes and Behavior. In Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Workshop on Economics and Information Security (WEIS 2003), College Park, MD, USA, 29–30 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.; Lee, J.S.; Chung, S. Optimistic Bias About Online Privacy Risks: Testing the Moderating Effects of Perceived Controllability and Prior Experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.A.; Healy, P.J. The Trouble with Overconfidence. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 115, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E.J. The Illusion of Control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 32, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D. Misperceptions of Feedback in Dynamic Decision Making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1989, 43, 301–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D. Modeling Managerial Behavior: Misperceptions of Feedback in a Dynamic Decision Making Experiment. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, G.; Bolsover, G.; Dubois, E. A New Privacy Paradox: Young People and Privacy on Social Network Sites. In Proceedings of the 109th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association (ASA Annual Meeting 2014), San Francisco, CA, USA, 16–19 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, G. Successful Failure: What Foucault Can Teach Us About Privacy Self-Management in a World of Facebook and Big Data. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2015, 17, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec Zlatolas, L.; Welzer, T.; Heričko, M.; Hölbl, M. Privacy Antecedents for SNS Self-Disclosure: The Case of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozani, M.; Ayaburi, E.; Ko, M.; Choo, K.K.R. Privacy Concerns and Benefits of Engagement with Social Media-Enabled Apps: A Privacy Calculus Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happ, C.; Melzer, A.; Steffgen, G. Trick with Treat—Reciprocity Increases the Willingness to Communicate Personal Data. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, Z. Can You See Me Now? Audience and Disclosure Regulation in Online Social Network Sites. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2008, 28, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddicken, M. The ’Privacy Paradox’ in the Social Web: The Impact of Privacy Concerns, Individual Characteristics, and the Perceived Social Relevance on Different Forms of Self-Disclosure. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 248–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienlin, T.; Trepte, S. Is the Privacy Paradox a Relic of the Past? An In-Depth Analysis of Privacy Attitudes and Privacy Behaviors. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.; Hargittai, E. Facebook Privacy Settings: Who Cares? First Monday 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.L.; Quan-Haase, A. Privacy Protection Strategies on Facebook: The Internet Privacy Paradox Revisited. Inform. Commun. Soc. 2013, 16, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Williams, E.J.; Joinson, A.N. “It Wouldn’t Happen to Me”: Privacy Concerns and Perspectives Following the Cambridge Analytica Scandal. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2020, 143, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, B. Click Here to Consent Forever: Expiry Dates for Informed Consent. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.; Ford, D.N. Tipping Point Failure and Robustness in Single Development Projects. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2006, 22, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repenning, N.P. Understanding Fire Fighting in New Product Development. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2001, 18, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmandad, H.; Repenning, N.P. Capability Erosion Dynamics. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 649–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.W.; Repenning, N.P. Disaster Dynamics: Understanding the Role of Quantity in Organizational Collapse. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Lee, H.S.; Park, M.; Moon, M.; Han, S. A System Dynamics Approach for Modeling Construction Workers’ Safety Attitudes and Behaviors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 68, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruutu, S.; Casey, T.; Kotovirta, V. Development and Competition of Digital Service Platforms: A System Dynamics Approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 117, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmandad, H.; Repenning, N.P.; Sterman, J.D. Effects of Feedback Delay on Learning. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2009, 25, 309–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, F.M. A New Product Growth for Model Consumer Durables. Manag. Sci. 1969, 15, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.L.; Shapiro, C. Technology Adoption in the Presence of Network Externalities. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 822–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquisti, A.; Brandimarte, L.; Loewenstein, G. Privacy and Human Behavior in the Age of Information. Science 2015, 347, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.S. Platform Economics: Essays on Multi-Sided Businesses; Competition Policy International: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.S.; Schmalensee, R. Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijck, J. Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data Between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology. Surveill. Soc. 2014, 12, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press Association. Hacker Advertises Details of 117 Million LinkedIn Users on Darknet. The Guardian. 2016. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/may/18/hacker-advertises-details-of-117-million-linkedin-users-on-darknet/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Bernal, N. Google Accused of Secretly Feeding Personal Data to Advertisers. The Telegraph. 2019. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2019/09/04/google-accused-secretly-feeding-personal-data-advertisers/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Wong, J.C. Facebook Confirms 419m Phone Numbers Exposed in Latest Privacy Lapse. The Guardian. 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/sep/04/facebook-users-phone-numbers-privacy-lapse/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Dodds, L. Phone Numbers of 11.5m Britons Leaked Online in Facebook Breach That Also Exposed Mark Zuckerberg. The Telegraph. 2021. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2021/04/05/phone-numbers-115m-brits-leaked-online-facebook-breach-also/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Meaker, M. Telegram, Signal, WhatsApp and Facebook: Which Is Better? The Telegraph. 2021. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/0/telegram-signal-whatsapp-facebook-better/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Meyers, E.M.; Erickson, I.; Small, R.V. Digital Literacy and Informal Learning Environments: An Introduction. Learn. Media Technol. 2013, 38, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debatin, B. Ethics, Privacy, and Self-Restraint in Social Networking. In Privacy Online: Perspectives on Privacy and Self-Disclosure in the Social Web; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Trepte, S.; Teutsch, D.; Masur, P.K.; Eicher, C.; Fischer, M.; Hennhöfer, A.; Lind, F. Do People Know About Privacy and Data Protection Strategies? Towards the “Online Privacy Literacy Scale” (OPLIS). In Reforming European Data Protection Law; Law, Governance and Technology Series; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2015; pp. 333–365. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, S.; Loewenstein, G.; O’Donoghue, T. Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review. J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 351–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy. J. Political Econ. 1957, 65, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E.; Marwick, A. “What Can I Really Do?” Explaining the Privacy Paradox with Online Apathy. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 3737–3757. [Google Scholar]

- Baruh, L.; Secinti, E.; Cemalcilar, Z. Online Privacy Concerns and Privacy Management: A Meta-Analytical Review. J. Commun. 2017, 67, 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Martin, K.D. Critical Roles of Knowledge and Motivation in Privacy Research. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 31, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandimarte, L.; Acquisti, A.; Loewenstein, G. Misplaced Confidences: Privacy and the Control Paradox. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013, 4, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; Kruikemeier, S.; Zuiderveen Borgesius, F.J. Exploring Motivations for Online Privacy Protection Behavior: Insights from Panel Data. Commun. Res. 2021, 48, 953–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, M.; Dienlin, T. Control Your Facebook: An Analysis of Online Privacy Literacy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Karahanna, E. Time Flies When You’re Having Fun: Cognitive Absorption and Beliefs about Information Technology Usage. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alashoor, T.; Baskerville, R. The Privacy Paradox: The Role of Cognitive Absorption in the Social Networking Activity. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2015), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 13–16 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trang, S.; Weiger, W.H. The Perils of Gamification: Does Engaging with Gamified Services Increase Users’ Willingness to Disclose Personal Information? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 116, 106644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.C. Facebook Says Nearly 50m Users Compromised in Huge Security Breach. The Guardian. 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/sep/28/facebook-50-million-user-accounts-security-berach/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Statista. Facebook’s Daily Active User (DAU) Figures in Europe from 4th Quarter 2012 to 1st Quarter 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/745383/facebook-europe-dau-by-quarter/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Statista. Facebook’s Monthly Active Users (MAU) in Europe from 4th Quarter 2012 to 1st Quarter 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/745400/facebook-europe-mau-by-quarter/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Statista. Number of Monthly Active WhatsApp Users Worldwide from April 2013 to March 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/260819/number-of-monthly-active-whatsapp-users/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Statista. Number of Monthly Active Instagram Users from January 2013 to June 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/253577/number-of-monthly-active-instagram-users/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Halliday, J. Google Agrees to Privacy Reviews to Settle Buzz Complaint. The Guardian. 2011. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2011/mar/30/google-privacy-reviews-buzz-ftc/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Hern, A. Closure of Google+: Everything You Need to Know. The Guardian. 2019. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/feb/01/closure-google-plus-everything-you-need-to-know/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Crain, M. The Limits of Transparency: Data Brokers and Commodification. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, R.S. Conformity and Character. Am. Psychol. 1955, 10, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönnies, F. Community and Society; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Learned Helplessness. Annu. Rev. Med. 1972, 23, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Park, J.; Jung, Y. The Role of Privacy Fatigue in Online Privacy Behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 81, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortesniemi, Y.; Kremer, J. Recommendations and Automation in the Consenting Process: Designing GDPR Compliant Consents. In Proceedings of the Legal Design as Academic Discipline: Foundations, Methodology, Applications, Groningen, The Netherlands, 12 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kortesniemi, Y.; Lappalainen, T.; Salka, F. User Attitudes Towards Consent Intermediaries. In Proceedings of the Legal Design as Academic Discipline: Foundations, Methodology, Applications, Groningen, The Netherlands, 12 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Motivation | Description |

|---|---|

| Entertainment | The relaxation, enjoyment, and emotional relief generated by temporarily escaping from daily routines. |

| Integration and social interaction | The sense of belonging (e.g., connectedness), the supportive peer groups (e.g., bandwagon), and the enhanced interpersonal connections associated with media use (e.g., community building). |

| Personal identity | The need to shape an identity through self-expression by sharing an image of this identity through self-presentation in order to gain self-assurance and self-recognition. |

| Information | The need to seek and share information, watch what others are doing (i.e., surveillance), and document personal information (i.e., lifelogging). |

| Remuneration | The expectancy to gain future benefits and rewards that basically stand apart from the behaviour. |

| Empowerment | The aim to exert influence or power on others by voicing opinions in order to enforce excellence and accuracy. |

| Explanation | Description |

|---|---|

| Rational risk assessment | |

| Privacy calculus | People perform a perfectly informed and rational cost-benefit analysis and decide to share their data only when the potential benefits of disclosure outweigh the expected privacy costs. However, people might still express concerns about their data being lost, resulting in the apparent inconsistency between expressed privacy concerns (or attitude) and actual behaviour. |

| Irrational risk assessment | |

| Incomplete information, bounded rationality, and decision biases | People compensate for limitations in information, time, and cognitive capabilities by using heuristics, which might still result in unexpected outcomes. Hence, the original intention or expressed attitude towards the behaviour might not be reflected in the actual behaviour. |

| Little to no risk assessment | |

| Social influence | People’s expressed attitude is apparently echoing their unbiased opinion. However, people’s actual behaviour is often affected by social factors. Hence, the expressed attitude is not necessarily reflected in the actual behaviour. |

| Obstacle | Description |

|---|---|

| Solvable | |

| Timing and Duration | Estimating costs is difficult due to timing of decisions and the typically unlimited duration of the consent. |

| Non-negotiability | The terms are not negotiable enough. |

| Scale | The cost-benefit analysis does not scale well to a large number of separate privacy decisions. |

| Challenging | |

| Aggregation | Data is aggregated and analysed to produce new data, leading to implicit disclosure of latent data. |

| Downstream Uses | Data flows to parties and purposes not foreseen at the time of consenting. |

| Cognitive Demands | The cognitive limitations of all human decision-making hamper cost-benefit analysis. |

| Insuperable | |

| Social Norm | Pressure to conform can strongly affect the decisions people make. |

| Social Data | Privacy decisions are framed as individual choices, but the data and the decisions can also affect others. |

| Explanation | Obstacle |

|---|---|

| Rational risk assessment | |

| Privacy calculus | The eight privacy obstacles reveal the futility of assuming a perfectly informed and rational cost-benefit analysis in privacy decision-making. |

| Irrational risk assessment | |

| Incomplete information, bounded rationality, and decision biases | Social Data, Aggregation, and Downstream Uses relate to issues that prevent access to complete privacy information. |

| Timing and Duration and Cognitive Demands relate to issues that prevent objectively right and unbiased privacy decision-making. | |

| Non-negotiability and Scale relate to issues that prevent real choice within boundary regulation. | |

| Little to no risk assessment | |

| Social influence | Social Norm refers to the social pressure that affects privacy decision-making as described by social influence. |

| Obstacle | Description | Causal Dependencies |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete information | ||

| Social Data | The data shared by users may directly reveal information about others. | Social Data is affected by Data Sharing and affects Aggregation, Downstream Uses, and Platform Value. |

| Aggregation | The platform analyses the data shared by users with the purpose to reveal additional information about them. | Aggregation and Downstream Uses are affected by Social Data, Privacy Concerns, and Privacy Control. In addition, they affect and are also affected by Online Privacy Literacy. |

| Downstream Uses | Data shared by users often reaches third parties outside the platform, and conversely data shared on other platforms often reaches the current platform. | |

| Bounded rationality | ||

| Timing and Duration | Privacy concerns gradually rise as more significant negative consequences develop and start to be realised over time. | Timing and Duration affect Online Privacy Literacy, while Cognitive Demands affect Privacy Concerns, Platform Value, and Social Pressure. |

| Cognitive Demands | Time and cognitive resources are limited and invested mostly in obtaining concrete and immediate benefits rather than learning about, understanding, and reacting to negative consequences. | |

| Real choice limitations | ||

| Social Norm | As the number of users grows, more potential users conform, adopt, and use the platform. | Social Norm affects Adoption, Discard, Engagement, and Disengagement Fraction. |

| Non-negotiability | The platform might not negotiate the processing of data. | Non-negotiability and Scale affect Privacy Control. |

| Scale | The platform’s privacy policy and settings could be lengthy and complex. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arzoglou, E.; Kortesniemi, Y.; Ruutu, S.; Elo, T. The Role of Privacy Obstacles in Privacy Paradox: A System Dynamics Analysis. Systems 2023, 11, 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11040205

Arzoglou E, Kortesniemi Y, Ruutu S, Elo T. The Role of Privacy Obstacles in Privacy Paradox: A System Dynamics Analysis. Systems. 2023; 11(4):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11040205

Chicago/Turabian StyleArzoglou, Ektor, Yki Kortesniemi, Sampsa Ruutu, and Tommi Elo. 2023. "The Role of Privacy Obstacles in Privacy Paradox: A System Dynamics Analysis" Systems 11, no. 4: 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11040205

APA StyleArzoglou, E., Kortesniemi, Y., Ruutu, S., & Elo, T. (2023). The Role of Privacy Obstacles in Privacy Paradox: A System Dynamics Analysis. Systems, 11(4), 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11040205