Abstract

Pressures sensed by the political system may lead to output failure, which can damage the effectiveness of government response but have rarely been analyzed in the literature of Chinese Internet studies. This research asks the following question: Why does the political system produce output failure in the online response process, in which the topic of government response does not align with the topic of the corresponding public message? Which factors can influence the possibility that the political system will produce an unmatched response? Engaging with the political system theory, we used topic modeling and sentiment analysis to analyze the online response data. The paper argues that the application of technology in government response adjusts the sensitivity of the political system to pressures. Factors including topic, emotion, and time can generate pressure on the political system. However, the political system is unable to detect a significant volume of stress, with digital technology expanding channel capacity.

1. Introduction

The Internet’s embedded values of freedom, equality, and democracy raise expectations for its political influence [1], sparking heated academic debates. However, scholars’ opinions are surprisingly divided into two distinct groups in terms of the political influence of the Internet in China. One side argues for the power-decentralization trend brought about by the Internet, which empowers public political participation [2,3,4]. On the contrary, the other group claims that the Internet strengthens the central power of political leaders without pushing forward government reform [5,6,7]. A consensus cannot be easily reached among studies on the political implications of the Internet in China.

Although disagreements exist, certain consensuses are established in online politics. There is a changing trend in online politics from constructing an internal network system to focusing on the external network system, which is characterized by two major characteristics: the government’s response to the needs of netizens and citizens’ influence on government through feedback mechanisms [1]. Similarly, this trend echoes in the analysis of the third stage of Chinese digital government development—the interaction between state and society—after the initial two stages, including internal office automation and inter-governmental information exchange [4]. Among diverse kinds of communications between the government and the public, government response to the public has strong potential for improvement. The traditional political communication between Chinese government officials and the public is seriously insufficient, as political information is noisy, heavily lost, distorted, and has low sensitivity and unbalanced feedback adjustments [8]. The application of the Internet in this communication process enables direct interactions between government officials and the public, which may potentially improve the ineffective traditional communication situation.

This research contributes to understanding the logic, operation, and function of the Chinese political system in the process of e-government response, especially when facing pressure from the environment. “E-government response” in this paper refers to how the government responds to public inquiries through digital communication channels such as official websites. The study interprets a common type of ineffective response—the topic of the e-government response does not match the topic of the initial public inquiry—as evidence that the political system is under stress. By analyzing the e-government’s varied perception of different types of pressure when responding to public inquiries, this study partially validates the applicability of the classical political system theory in the context of Chinese e-government response. Furthermore, practical suggestions to improve the effectiveness of e-government response are raised based on the critical discussions of the theory and the empirical evidence.

2. Literature Review

The concept of “government response” did not originate in China but rather in Western countries as a response to their governments’ legitimacy crisis, which arose as a result of the economic depression from 1960s to 1970s [9]. Scholars raise definitions of this concept from different perspectives including public policy, public demand, and government-citizen interaction. In the Western democratic context, some scholars define this concept as public expressions, which include opinion polls, demonstrations, elections, and letter campaigns, that are adopted by the government for public policies [10,11]. It can also be perceived as the government’s response to public demands in order to align with the people’s preferences [12]. In the Chinese context, this concept is understood as the process by which the government interacts with citizens [9]. Due to the specific focus of this article, we define e-government response as governmental replies to public inquiries with the aim of solving public concerns through official websites.

The importance of government response to public opinion can be unpacked from three major perspectives including modern politics, political legitimacy, and public rights. The continuous response of the government to the opinions of citizens is regarded as the basic characteristic of the modern political system [13]. This significance can also be explained from the perspective of political legitimacy, as more people will be loyal to the state if most public requests are responded to specifically and sufficiently by the political system [14]. In contemporary China, where politics and administration are integrated, responsiveness is regarded as the most fundamental basis of legitimacy [9]. It is even incorporated into “the Main Evaluation Criteria for Chinese Democratic Governance” [8]. From the perspective of public rights, an effective government response ensures citizens’ rights of communication, information access, and disclosure [9]. All of these demonstrate the significance of government’s response to public opinion.

It is conducive to explaining the relevant phenomenon if we can understand the motivation of the Chinese government response. Scholars attempt to explain the motivation of the Chinese government’s response to online public opinion in terms of authoritarian resilience and fear of potential public protests. The responsiveness of the Chinese government is understood as an initiative reflecting authoritarian resilience [15]. Another way to understand the response motivation is that the authority is fearful of the public’s collective action in response to official inaction [16] and the potential public protests when the media follows up [17]. The understanding of the Chinese government response becomes more complex as the attitude of the government towards online public opinion is ambivalent, with official emphasis on online public opinion during foreign affairs [18], online censorship [19], and manipulations [20,21] coexisting.

Research on Chinese e-government responses focuses on limited perspectives without demonstrating whether and when government responses effectively solve public concerns. Scholars explore the influence of different factors on whether the government responds or not and the policy impact generated by online expressions. Based on the analysis of government response data from the Message Board for Leaders of the Renmin Net, it was found that both social identities of netizens and policy categories of public messages influence whether the government responds or not [22]. Through conducting an online field experiment, the claim of a collective action organization and the reference to upper levels of government are more effective in generating government responsiveness at the county level compared with tabbing as a sign of loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party [23]. Regarding the policy impact of online public opinion, scholars argue that the stronger official stress on policies of social welfare was triggered by online expressions through content comparison between public expressions on the Message Board for Leaders and Government Work Reports [24]. However, existing studies have rarely investigated if the official replies effectively address the public concerns reflected online. If not, a typical situation of an ineffective response is when the topic of the government response does not align with the topic of the initial public message posted online (da fei suo wen), which is referred to as an “unmatched government response” in the following discussions. Very few studies have investigated the reason why the government generates an e-government response in which the topic does not match the initial inquiry.

This kind of unmatched government response does not fully process inputs and reflects the information loss or distortion in transmission. It can to some extent reflect the sensitivity of the political system to certain pressures or stimuli in the form of expedient measures. By obscuring formal responses, it aims at dispelling possible public dissatisfaction caused by temporarily unresolved public demands. Instead of a substantial response, an unmatched government response is a pro-forma response that meets the official requirement of response rate but does not substantially solve the problem. If the official response specifically and accurately addresses public concerns and establishes a clear connection between the political system and the social system, the unmatched government response forms a vague link between these two systems. Although it may meet the time requirement and ensure the response rate as stated in the official documents [25], specific public inquiries are not substantially resolved. The study of it may help to explain the regularity of the political system’s sensitivity to pressure and stimulus. A typical example of an unmatched government response appears on the official website of the Beijing Municipal Government an astonishing 1160 times from 2019 to 2020. It seems to work as a panacea in the officials’ eyes for all public inquiries relevant to the lottery policy of car numbers, no matter what specific questions are initially proposed by the public:

“In order to alleviate traffic congestion, reduce energy consumption and reduce environmental pollution, and achieve a reasonable and orderly growth in the number of passenger cars, the city of Beijing has implemented a policy of regulating the number of passenger cars since 2011 and has achieved remarkable results. The increased number of passenger cars has been effectively controlled, which plays an important role in alleviating urban traffic congestion and improving the atmospheric environment. According to the “Beijing Interim Provisions on the Control of the Number of Passenger Cars” (Government Order No. 227), “the Decision of the Beijing Municipal People’s Government on Amending the Beijing Municipal Government’s Interim Provisions on the Control of the Number of Passenger Cars” (Municipal Government Order No. 276) and its implementation rules, the city’s passenger car quotas are configured in an open, fair and just way. In the process of policy implementation, the city’s passenger car quota management integrates the opinions and suggestions of the city’s people’s congress representatives, members of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and the general public to continuously improve control measures. The city has adjusted the total number of quotas and allocation methods for passenger cars, increased the chances of long-term lottery applicants to win the lottery, increased support for new energy passenger cars, and further ensured the orderly progress of the number of passenger cars. In the next step, we will extensively listen to opinions and suggestions from all walks of life, consider the actual problems encountered in the regulation and control of passenger cars, and strive to study and improve relevant policies for the regulation and control of passenger cars”.

This article focuses on the official website of the Beijing Municipal Government, which is called “the Window of the Capital”. As a local online platform, it closely links residents of Beijing and government officials through digital connections with 83 government departments and affiliated institutions. This extensive network of connections is beneficial in addressing public concerns in a targeted manner. The process of response there forms its own political system and, at the same time, works as a political sub-system within the whole Chinese political system of response. The inputs and outputs of this website illustrate the response operation logic of a typical political sub-system at the city level, if not the whole political system. The reason to choose this case is because of its outstanding performance in facilitating interactions between government departments and citizens, which offers the opportunity of revealing the operation logic of the political system based on a representative political sub-system. The Window of the Capital has been ranked first among peer local government websites for the past 12 consecutive years for government online interaction with citizens. It used the Internet early on to interact with netizens through the use of an integrated platform. The operation of this local platform reflects the innovation and autonomy of a representative political sub-system in the digital response context. The study of this political sub-system is not only much more feasible than direct exploration of the entire system, but it also mirrors the function logic of the political system to some extent.

3. Theory and Research Questions

The process of e-government response is a political phenomenon containing both typical input and output, which should be systematically approached and perceived. The political system theory regards politics as a system within the environment, which exerts influence on the “input” containing requirements and support for the political system. After processing the input, the authority within the political system generates output for the general environment, from which feedback can be returned to the political system. The reaction of the political system to the environment reflects the way in which the system functions [26]. The political system theory is well suited for explaining the phenomenon of the unmatched e-government response, as the process contains both typical input and output, which are key factors of this theory. The online public message is a specific form of input, which mainly refers to interest expression here. In the eyes of Edward Almond, interest expression is regarded as both input and an important function of the political system [27]. The e-government response process can be regarded as a special function of boundary maintenance between the political system and the social system. The traditional output of the political system theory is public policy, which is defined by its macroscopic nature. In China, public policy as the traditional output lacks evaluation and feedback that are visible for both the political system and the social system. In the context of online response, the output of the political system is official replies, with the new feature of being specific and targeted and containing the possibility of being evaluated by the public. With the new dynamics of the boundary maintenance, the political system may encounter problems with output effectiveness. A typical problem is that the topics of some government responses as “output” do not align with the topics of the corresponding initial public messages posted online as “input”. An example of the general and ineffective response to the inquiry about the car number lottery policy is mentioned earlier in the section above. One of the typical situations of output failure is when the output does not conform to the actual situation or is inconsistent with the requirements of the system members [26]. Through this understanding, the mismatch between the topics of the government response and the public message is a typical situation of “the output failure” [28] as well as the disfunction of the political system.

The investigation of the causes of political system dysfunction naturally leads to the following research questions: Why does the political system generate output failure in the online response process, where the topic of the government response does not align with the topic of the initial corresponding public message? Which factors can influence the possibility of generating an e-government response in which the topic does not match the initial inquiry? The exploration of these questions is conducive to understanding how the Chinese political system copes with the changing environment of the digital response context so as to effectively address or just ineffectively respond to public concerns. The investigation of the influencing factors may reveal the specific types of inputs from the environment to which the political system is most sensitive or least responsive. This may further inspire the reform and modification of the political system from the perspective of online responses for a better state–society relationship.

The application of information and communication technology (ICT) to government response not only alters the information channel but may also change the political system’s perception to pressure. Not all elements contained in the input generate pressure on the political system. Even if they do, the stress levels may not be the same. Thus, it is necessary to explore separately whether different elements put significant pressure on the political system. Elements that may generate pressure on the political system include content, volume, emotion, and time. Easton [28] proposed two types of output pressures that have a negative impact on the political system: content pressure and volume pressure. The “content pressure” refers to the stress that is faced by the political system and caused by the substance of input. For online responses, certain topics raised by the public may put pressure on the government, as these issues are hard to address through one-time replies. From this perspective, we may have the first hypothesis (H1a): that the substance of the initial public message posted online may influence the level of topic match of the corresponding government response. On the side of volume pressure, “the excessive volume stress” [28] describes the dangerous situation faced by the political system when the input capacity of the requirement is too large. In the context of government response, the possible logic guided by this theory is that the greater amount of public messages received by a certain department, the more difficult it is for this department to allocate enough resources to each message, and the easier it is for the government response to not match the initial inquiry. Therefore, another hypothesis (H1b) is that the larger the number of public messages received by certain government departments, the higher the possibility of generating topic-unmatched responses.

In the response procedure, online public messages enter the political system as interest expressions that happen at the boundary between the social system and the political system. Interest expression determines the characteristics of the boundary and the model of boundary maintenance [27]. One of the important dimensions of the characteristics of interest expression is emotion, which may form another type of pressure for the political system. The more emotional the expression of interest is, the more difficult it is to integrate and transform it into public policies [27]. Information with strong emotion makes analysis and reasoning difficult, as the political system cannot easily evaluate or weight the emotional information so as to fill it into the flow of political input and output [27]. In the response context, public messages with extreme emotion could obscure the description of issues and reduce the rationality of expressions, which may damage the accuracy and specificity of official replies. Thus, we generate the second hypothesis (H2): that the stronger the emotion of public messages, either positive or negative, the harder it is for them to trigger a matched e-government response.

Aside from content, volume, and emotion, government communication as a branch of the political system theory offers another valuable perspective on the phenomenon of response. Information communication is emphasized as being central to the governance process and is regarded as “the nerve of government” [14]. According to this viewpoint, the government is “steering” rather than controlling [14]. Guided by communication flows and feedbacks [14], the “steering” process is interpreted as ongoing movement, continual adjustment of strategy, and sensitivity to the environment [29]. The unmatched government online response can be regarded as a specific form of ineffective steering without the guidance of sufficient communication and adequate feedback. Karl Deutsch further raised major concepts to explain the steering process, including “lag” and “gain”. “Lag” refers to the time the political system takes to react to information, while “gain” means the extent of government reaction, which could be less, more, or exactly what the public requests [30]. Time can exert a unique type of pressure on the political system. The longer the “lag” process is, the less likely the political system is to achieve the goal [14]. Thus, the longer the government takes to process information during the “lag”, the less effectively they can “steer”. If it takes too long for the government to prepare the response, the effectiveness of resolving the initial public concern is questionable. Following these interpretations, the third hypothesis (H3) is that the longer the government departments take to respond to online public messages, the less likely the public receives the matched official replies.

4. Research Methods

Shared by the Department of Technology at the Window of the Capital, the whole dataset of government responses covers every item of everyday public messages and government replies on the Beijing Municipal Government website from 2019 to 2020. As the data are based on the population of local government responses across a time period, it minimizes the selection bias of sampling. In total, it includes 272,707 observations, with each one containing corresponding attributes including “category of message”, “title of message”, “content of public message”, “time of the message posted online”, “time of government receiving message”, “department of government reply”, “time of government reply”, and “content of government reply”.

In this study, the method of topic modeling is employed to generate the dependent variable pertaining to the adequacy of the government’s response to the public’s demands or, alternatively, whether the public’s complaints led to high-quality responses from the government. The transfer of the research focus from the traditional emphasis on response or not to the quality of text in political interaction is the essential reason of choosing topic modeling as the research method. This method can automatically calculate the probability distribution of topics in the text data, which are contained in the attributes “content of public message” and “content of government reply”. As the process by which the political system converts input into output is invisible, the logic and law of the information transformation process of the political system can be indirectly analyzed by topic modeling the textual features of input and output. This method considers each topic of “content of public message” and “content of government reply” as a probability distribution. For example, text A has a 70% probability of belonging to the illegal construction topic and a 30% probability of belonging to the traffic topic. At the same time, the topic model also considers the relationship between each topic and word frequency in the article as a probability distribution (and that a word belongs to a certain topic regardless of its order in the text, which is the “bag of word”). With known document-word information, we can estimate document-topic distributions and topic-word distributions through iterative estimation [31]. By using this method, we can generate topics for each data point in “content of public message” and “content of government reply” and use their similarity as an independent variable to generate our dependent variable—whether or not the government has responded correctly to public concerns. By combining with other attributes, further analysis can be conducted to explore the specific situation and explain the reasons why matched and unmatched government responses can be generated. Popular topic modeling approaches include latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) [32] and structural topic model (STM) [33]. They aim at identifying topics from a large amount of unstructured texts [34] with the basic assumption of a “bag of words”, which means the order of terms in a document can be changed without affecting the results of model training [35]. The structural topic model (STM) was chosen for this paper because it incorporates the effect of the covariate on topic prevalence and provides a more accurate prediction of topic distribution [33,36,37].

Topic modeling has been applied to politics, public administration, and media studies with the focus on analyzing relevant texts. Researchers investigate the research–practice gap in public administration by topic modeling the titles and abstracts in Public Administration Review and articles in Public Administration Time [34]. It can also be used to explore the political consequences of online expression by comparing the topic of online public messages and public policies in China [24]. In addition, another area of applying topic modeling is to analyze journalistic texts, as there is large number of texts produced in this field [38,39,40]. However, certain limitations of this method exist, as it requires tailored validation and cannot replace human reading and thinking [41].

In topic modeling, researchers need to specify the parameter K. The value of K represents the number of topics in topic modeling. The machine cannot automatically decide this value, which requires human input. There are three main methods for the selection of the K-value: perplexity (held-out likelihood), exclusivity, and semantic consistency. Scholars regard perplexity as defective among them, so the selection of K-value in recent publications has rarely relied on perplexity. This article uses four methods, namely method semantic coherence, exclusivity, residuals, and held-out likelihood, to select parameter K. Semantic coherence is maximized when the most probable words in a given topic frequently co-occur together. Mimno et al. [42] showed that the metric correlates well with human judgment of topic quality. Let D(, ) represent the number of times the words and appear together in a document. Then, for a list of the M most probable words in topic k, the semantic coherence for topic k is given as Equation (1). Because the range of values inside the logarithmic brackets on the right is (0,1), a larger semantic coherence indicates that there are more co-occurrences of words within each topic in the model, which means that the model is better.

A word’s exclusivity to a topic is its usage rate relative to a set of comparison topics [43]. The greater the exclusivity of words in the model, the better the model. Residuals describe the degree of variance of the multinomial within the data-generating process of STM. The greater the degree of variance, the worse the model. Increasing the number of topics can usually absorb excess variance in the model. The idea of held-out likelihood is similar to cross-validation, where a portion of words are removed from the document, and the probability of their occurrence in the correct position is estimated. The higher the probability, the stronger the model’s predictive ability.

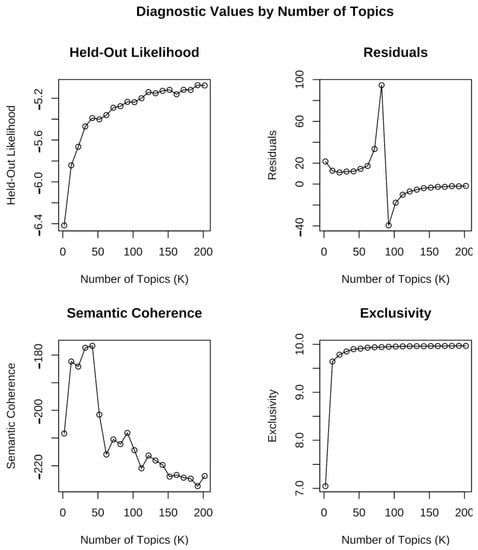

To optimize the value selection, both the exclusivity and the semantic coherence metrics are expected to be as large as possible. In this paper, we rely mainly on these two metrics and supplement them with held-out likelihood1 and residuals check to select K values. We also check whether the indicators are overspread when extra topics are required [44]. None of these metrics, with the primary role of assisting, are a fixed law for K-value selection. The semantic consistency keeps increasing until K reaches 50. The exclusivity increases monotonically and slows down when Kis around 50, where the marginal utility of K starts decreasing (see Figure 1). Together with the consideration of held-out likelihood and residuals, we choose 50 as the appropriate K value.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic Values by Number of Topics.

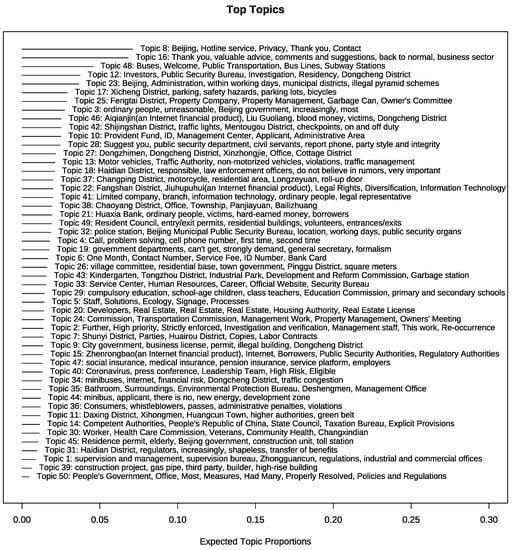

The specific tag for each topic is summarized based on the words, which appear the most frequently under each topic. Figure 2 illustrates the top five most frequent phrases for each topic and the topic proportion after using the frequent and exclusive (FREX) method. We use the method of FREX to measure the percentage of words, as it has been justified and advised in the relevant literature [33]. FREX is the weighted harmonic mean of the word’s rank in terms of exclusivity and frequency [44]. We summarize the tag for each topic based on the corresponding high-frequency phrases due to their frequent appearance. To some extent, the topic proportion can measure the prominence of each topic in public expressions and government responses. It can be found that the high-frequency words are more differentiated and weakly correlated between topics, while within the topics, the correlation of high-frequency words is stronger, which also justifies the selection of K= 50. To simplify the analysis, we classify the 50 topics into 16 clusters based on their similarity. Table 1 illustrates the classification logic and result. We decide against directly setting K to 16. The reason is that the model using 16 as the K value in the structural equation is not as well fitted as the model with a K value of 50.

Figure 2.

Topic Proportion and Top Frequent Phrases.

Table 1.

Topic classification.

Apart from topic modeling, we also use sentiment analysis. The reason to choose sentiment analysis is that this method can quantify the extreme level of emotion, which lays the foundation for further correlation analysis between sentiment and unmatched government response. We use the API of the Baidu AI Open Platform to analyze online messages2. Baidu is one of the largest and most technologically advanced technology companies in mainland China. The sentiment analysis is based on the ERNIE 2.0 model developed by Baidu [45], which outperforms BERT in Chinese natural language processing and is one of the strongest models in this field. For each online message, this model helps us to generate the corresponding positive and negative probabilities of sentiment. We then calculate the absolute value of sentiment for each message by deducting the negative probability by the positive probability, which measures the level of extreme sentiment relative to the neutral sentiment. In order to test the hypotheses raised, we run logistic regression by taking the value of topic clusters, department, response interval, and the absolute value of sentiment as independent variables. For the dependent variable, we choose whether the government response matches the public inquiry as a binary dependent variable. is the controlled covariates such as message type, date, and text length. Our model is shown in Equation (2)3:

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. The Characteristics of Evolution

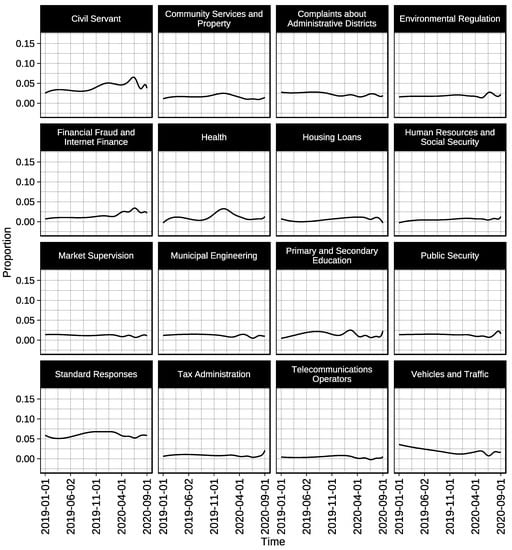

Understanding the evolution characteristics of topic clusters is necessary because they may reflect substance concentration and environmental change, both of which can affect the characteristics of inputs to the political system. Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of average proportions of 16 topic clusters from 2019 to 2020. Most of them present relatively steady trends by positioning their propositions between 0% and 5% throughout these two years, while some other topics present advantaged proportions or obvious fluctuations. The evolution of the average proportion of the cluster standard responses is steadily above 5% for most of the time, which echoes the surprising repetition of standard response illustrated earlier in this paper. It also demonstrates the severity of ineffective responses in the form of general and standard replies, which can be regarded as “output failures” of the political system [28]. In addition, the evolution depicts the impact of environmental change on the political system. As the environment influences “input” [28], a change in the public health environment in early 2020 may increase the volume pressure on the political system, as evidenced by the sudden lift of the health cluster curve. This is possibly due to the outbreak of COVID-19, which can be regarded as a sudden alteration of the environment and caused the concentrated public concerns posted online.

Figure 3.

The Evolutions of the Average Proportions of Topic Clusters.

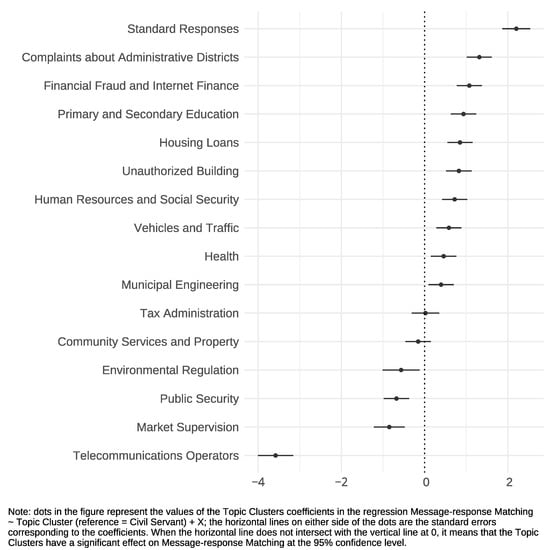

5.2. The Content Pressure

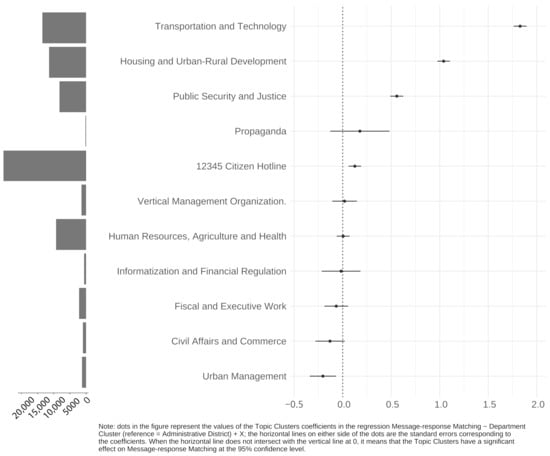

As the first element potentially generating stress, content pressure does exist in this political sub-system, as most clusters of topics have a significant effect on message-response matching (Figure 4). Public inquiries as inputs referring to certain topics can effectively stimulate the political system for corresponding responses. However, if public messages as inputs contain some other topics, the political system may not function well to generate official responses as outputs referring to similar topics. This outcome aligns closely with the assertion of the classical political system theory that content pressure can generate a negative impact on the political system, which may damage its capacity to generate certain outputs [28]. As shown in Figure 4, the correlation coefficients of certain topic clusters are negative, and these clusters have significant effects on message-response matching at the 95% confidence level. This means that it is highly likely that the government cannot provide an official response containing similar topics to the public message when touching on topics belonging to these categories. Typical ones include telecommunications operations, market supervision, public security, and environmental regulation. From 2019 to 2020, telecommunication fraud cases were relatively common in China. The authority seems easily incapable of directly addressing relevant issues simply through the format of an online response. These categories generate content pressure for the government, which damages the effectiveness of online responses. However, if the interaction is related to another topic with little content pressure, the government’s responses tend to easily align with the topics of these inquiries. These categories of topics include but are not limited to complaints about administrative districts, financial fraud, primary and secondary education, and so on. We can see the online response channel has the strong potential to work effectively on solving issues in these areas, which may represent the authorities’ policy priorities. Thus, the hypothesis (H1a) is supported by the evidence: the topics of the online public messages can influence the possibility that the corresponding government responses match the topics of the initial public inquiries. In the e-government response process, there is content pressure.

Figure 4.

Correlation between Message-response Matching and Topic Clusters.

5.3. The Volume Pressure

Different from the coordination of the content pressure, digital technology as the information channel reduces the sensitivity of the political system to the volume pressure. Evidence supports that the volume of online public messages does not really form output pressure for this political sub-system in the online response process. The government departments receiving a large number of online inquiries may not easily generate responses containing distinct topics with the initial public messages. Although the traditional political system theory argues that the volume of inputs may form stress to damage the capacity of the political system to generate certain output [28], it seems like there is no existence of the volume pressure in this case where digital technology works as information channel. In contrast to the classic theory, most clusters of government departments4 receiving a large number of online public messages tend to align their replies quite well with the topics of the initial public inquiries, with typical examples including transportation and technology, housing and urban–rural development, public security, and justice (Table 2) (Figure 5). Clusters of government departments receiving a relatively small number of messages, on the other hand, may not perform well, with high chances of generating an unmatched response. A typical example is urban management, which receives a relatively small number of messages but has a significant negative effect on message-response matching at the 95% confidence interval. Easton (1965) introduced the concept of “excessive volume stress” to describe the negative impact on the political system’s ability to generate output when the amount of inputs exceeds the processing capacity of the political system [28]. Contrary to this assertion, despite the fact that the work load suffered by those clusters of departments receiving a relatively large number of inquiries seems much higher than the work stress of other clusters, they still successfully generate official responses to align effectively with the public inquiries. Together with the verification of the content pressure in the above section, it seems like the content of the initial public message posted online matters much more than its volume in exerting impact on the government response to align with the public inquiry. Hence, the hypothesis (H1b) is not supported in this study: the large number of public messages received by certain government departments does not necessarily lead to the high possibility of generating an unmatched official response.

Table 2.

Department classification.

Figure 5.

The Number of Messages for Government Departments and the Correlation between Message-response Matching and Government Departments.

The reduced sensitivity of the political system to the volume pressure can be explained by the expansion of channel capacity, the increase in government administration efficiency, and the characteristics of online response. Digital technology expands the volume of the information channel, which satisfies the demand of delivering a large number of messages. From 2019 to 2020, there were more than 270,000 public messages posted on this portal and transferred to corresponding government departments for response. This processing scale of information cannot be imagined without the application of digital technology. The expansion of channel capacity is conducive to easing the stress of information overload. Although volume pressure does not seem to exist in online response, the idea of channel modification echoes in the work of David Easton as “the creative adjustment of the channel”: through creative adjustment of the channel capacity, a system can handle the demands of higher loads, which eases the stress of overloading [28]. Apart from the channel expansion, the application of digital technology also increases the efficiency of government response. Instead of the traditional interest groups, there are professional transferors (zhuanban ren) designed at the website to categorize, shunt, and deliver public messages to the corresponding government departments. This professionalization brought by digital technology in processing information greatly increases response efficiency, which increases the capacity of the political system to handle the large volume of information. Furthermore, the characteristics of online response as an output also reduce the potential influence of volume on the political system. E-government response as output mainly covers one-time replies without referring to constrained decisions, which are the traditional output and bring much more work load on average to the political system than simply one-time replies. With the increase in information volume as an input, the marginal pressure of these inputs on the political system can be very small.

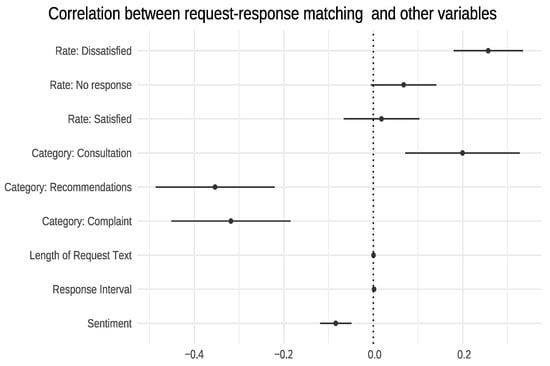

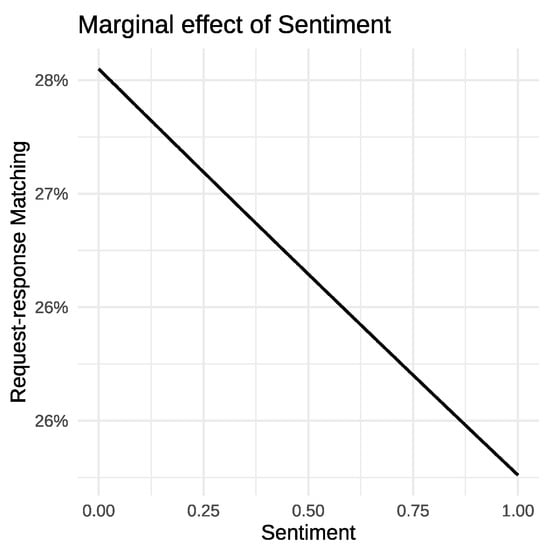

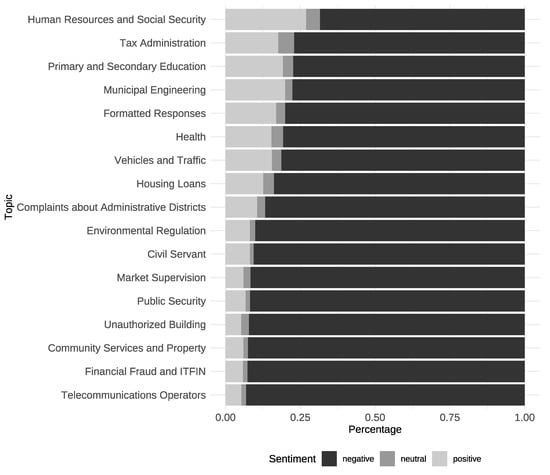

5.4. The Power of Sentiment

After analyzing the potential pressure brought by content and volume, we shift the focus to sentiment. The application of digital technology has not adjusted the sensitivity of the political system to emotion or sentiment. Sentiment generates a significant impact on message-response matching. The more emotional the online message is, the less likely it is the government’s response will align well with the initial inquiry. The public messages posted online to some extent can be regarded as interest expression by the public. As argued by Gabriel Almond, the more emotional the expression of interest, the more difficult it is to be integrated and transformed into public policies [27]. This is because, as information, input with strong emotion makes analysis and reasoning difficult. The political system cannot easily evaluate or weight emotional information, making effective incorporation into the flow of political output difficult [27]. This reasoning about the impact of emotion is also well supported by the evidence of the Chinese government’s online response. The logistic regression of the absolute sentiment and whether the reply matches the message reveals that if the absolute sentiment increases by one unit, the possibility of the government response matching the initial inquiry decreases by around 4%, with the correlation coefficient being −0.157 and p < 0.001. As Figure 6 presents, the standard error of the correlation between the sentiment of the public message and the topic matching is very small. Therefore, the hypothesis (H2) is supported: the stronger the emotion of public messages, the more difficult it is for them to trigger a matched e-government response.

Figure 6.

Request-response Matching and Other Variables.

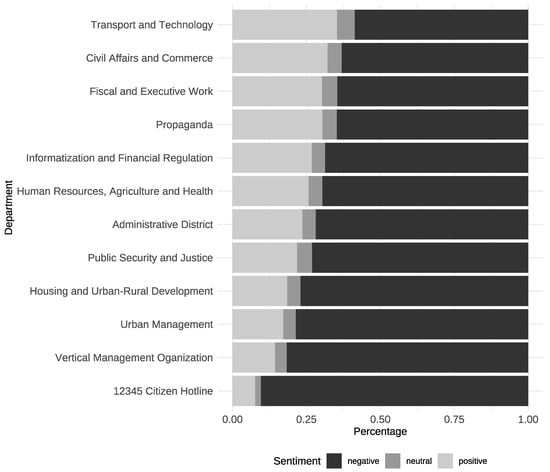

We cannot separate sentiment from other factors as they are closely connected to each other. The characteristics of sentiment distribution reveal that negative sentiments prefer to appear in certain categories of messages, government departments, and topics. The Beijing Municipal Government website classifies the public messages posted there into four categories including consultation, suggestion, complaint, and report. The percentages of messages with negative sentiments in the categories of complaint (90.49%) and report (96.52%) are much higher than those percentages in the categories of consultation (71.00%) and suggestion (53.44%) (Table 3), which justifies the result of sentiment analysis. From the perspective of government departments, clusters of the 12345 citizen hotline, vertical management organization, and urban management contain much higher percentages of negative sentiment compared with clusters of transportation and technology, civil affairs and commerce, and fiscal and executive work (Figure 7). For sentiments in specific topics, topics in clusters of telecommunications operations, financial fraud and ITFIN, and community services and property contain relatively higher proportions of negative sentiments than topics in clusters of human resources and social security, tax administration, and primary and secondary education (Figure 8).

Table 3.

The Sentiment Distribution in Categories of Online Messages.

Figure 7.

Marginal Effect of Sentiment.

Figure 8.

The Distribution of Sentiments Percentages in Clusters of Departments.

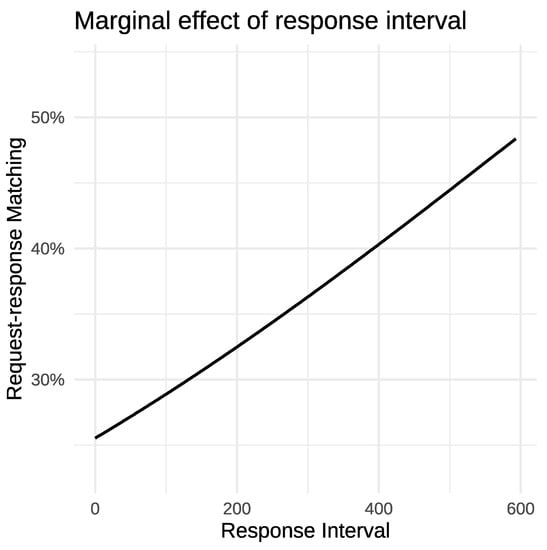

5.5. The Impact of “Lag”

In addition to topics and sentiment, the length of time that the government department takes to respond can also influence the possibility that the official response can match the public message. The government’s activities are perceived as a “steering” process, which is understood as ongoing movement, continual adjustment of strategy, and sensitivity to the environment [29]. All of these activities are guided by communication flows and feedback [14], which take time for the political system to effectively respond to. “Lag” refers to the time taken by the political system to react to information, and “gain” means the extent of government reaction [14]. The longer the “lag” is, the smaller the possibility for the political system to achieve the goal [14]. Following this logic, the longer the political system takes to consider the information contained in the online inputs, the less efficient the official outputs are, and the less likely it is for the official response to match the public message. The Chinese e-government response data verify that time constraints do exist, but their function in the political system changes in the digital response context. As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 9, the response interval is positively correlated with whether the government response matches the public message, although the point estimate value is only 0.002. The marginal effect of the response interval further verifies the positive relationship with the request-response match (Figure 10). With the response interval becoming larger, the percentage of request-response matches increases significantly. The marginal effect of the response interval demonstrates that the coefficient of the response interval in the dot-whisker plot underestimates its actual impact on the matching degree. Thus, the real-world operation logic of digital government response could be that it takes time for this political sub-system to adequately absorb and adopt information before generating suitable government reactions. The valuable information contained in communication and feedback requires a sufficient processing time before it can guide the adjustment of strategy and the movement of the political sub-system. Therefore, the hypothesis (H3) is not supported, as evidence shows that the longer government departments take to respond to public messages, the more likely it is that the official response matches the initial inquiries.

Figure 9.

The Distribution of Sentiments Percentages in Clusters of Topics.

Figure 10.

Marginal Effect of Response Interval.

6. Conclusions

According to the classic political system theory, before the widespread adoption of digital technology in governance, the political system established a specific mode of processing pressure. The application of the Internet in government response could bring another set of behavioral patterns to the political system for sensing and processing pressure. With the Internet working as an information channel, the government can harness certain pressures that may have a negative impact on the political system, such as the volume pressure. This article adopts topic modeling and sentiment analysis to explore the factors that can potentially influence the failure of the online response of a political sub-system, if not the entire political system. It argues that the application of digital technology in government response adjusts the sensitivity of the political system to pressures in the informational communication between the political system and the social system. Topics, sentiment, and the response time interval can still generate pressure on the political sub-system by influencing the possibility of whether the government response aligns well with the public inquiry. Topics can influence the likelihood of a match between public inquiries and government responses. The hypothesis (H1a) was proven: the topics of the online public messages are significantly correlated with the possibility that the corresponding government responses match the topics of the initial public inquiries. When it comes to clusters of telecommunication operators, market supervision, public security, and environmental regulation, it may be difficult to effectively address public concerns posted online with a single response. The research positively verified the hypothesis (H2): the stronger the emotion of public messages, the more difficult it is for them to trigger a matched e-government response. Furthermore, the study proved the hypothesis (H3): the longer the official response interval is, the more likely it is that the government response will align with the public message. However, as digital technology expands the capacity of the information channel, the political sub-system is not sensitive to volume pressure. This study did not prove a significant positive correlation between the number of public messages received by certain government departments and the possibility of generating an unmatched official response, which fails to verify the hypothesis (H1b). This paper provides concrete evidence of the potential impact factors of ineffective government response, which aids in understanding the causes of ineffective political response in general. This may inspire further changes to the political mechanism in terms of topic identification, sentiment perception, and response time adjustment in order to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of government response in the digital context.

This paper reviews the political system theory, especially from the perspective of the effectiveness of “output” in the response process. It could be worthwhile to rethink this theory in the context of the Chinese government’s online response, as evidence supports that the volume of inputs does not really create pressure for the government to effectively address public inquiries, and the logical relationship between “lag” and “gain” does not follow the original theory. With the shift of the information communication channel from the interest group to Internet connectivity, we should reconsider the volume pressure argument in the political system theory. The increased volume of public inquiries does not necessarily increase the likelihood of output failure. This may relate to the operational logic modification of the political system after adopting the Internet for the function of response, which requires further investigation. In the online response context, the longer time of “lag” to process information on the political system may not negatively influence the achievement of political goals. Rather, the longer the “lag”, the greater the possibility of effective responses that correspond to original public concerns. However, some classic components of this theory are still supported by evidence in the digital response context, such as the pressures of content and sentiment. In the context of digital response, it appears that the political system theory can only partially explain the reality and logic of a typical Chinese political sub-system. This necessitates reconsidering the theory’s suitability for application to the digital contexts of other countries, which necessitates additional research. Due to the constraints of the resources, there are some limitations of this study, as the online response dataset was collected only from the Beijing Municipal Government website. If relevant data are available, comparing the influential factors of the response match for governments in different countries would be interesting. It would be interesting to compare the influential factors of the response match for governments of different countries if relevant data are available. It is also worthwhile to further investigate the logic and process of the unmatched government response by conducting interviews with government officials in relevant departments. More information could potentially be revealed by insiders about the government response mechanism, which is not covered by the online data. The endeavor of scholars to understand the response of the political system in the digital context will continue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and W.W.; methodology, W.W.; software, W.W.; validation, W.W.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, Z.L. and Q.M.; data curation, Z.L. and Q.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and W.W.; visualization, W.W.; supervision, Q.M.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Introduction Plan of the Postdoctoral International Exchange Program grant number (YJ20210101), and the APC was funded by the Introduction Plan of the Postdoctoral International Exchange Program grant number (YJ20210101).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy of the Official Website of the Beijing Municipal Government.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by Lida Wang, Hui Qiao, Shaotong Zhang, and Youkui Wang for this research, especially for the conduct of interviews and the access of data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | To evaluate the model’s performance, we use a method similar to cross-validation in which some data are removed from the estimation and used for validation. |

| 2 | See https://ai.baidu.com/ai-doc/NLP/3k6z52edg (accessed on 10 March 2022). |

| 3 | Where is the binary variable of whether the message and response match, Topic, Department, Emotion and Interval are the main independent variables in this paper, and XCov is the controlled covariates such as message type, date, and text length. |

| 4 | To simplify the analysis, we classify 83 government departments into 12 clusters according to the division of responsibilities of vice mayors of the Beijing municipality (http://www.beijing.gov.cn/gongkai/sld/szfld/ (accessed on 20 September 2022)). Table 2 illustrates the classifications. As “12345 Citizen Hotline” is a separate channel connected with the Beijing Municipal Government Website, we treat it as an individual cluster. |

References

- Chadwick, A. Internet Politics: States, Citizens, and New Communication Technologies; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, L.K. The Electronic Republic: Reshaping Democracy in the Information Age; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Taubman, G. A Not-So World Wide Web: The Internet, China, and the Challenges to Nondemocratic Rule. Political Commun. 1998, 15, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Technological Empowerment: The Internet, State, and Society in China; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coursey, D.; Donald, F.N. Models of E-Government: Are They Correct? An Empirical Assessment. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalathil, S.; Boas, T.C. Open Networks, Closed Regimes: The Impact of the Internet on Authoritarian Rule; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stockmann, D.; Gallagher, M.E. Remote control: How the media sustain authoritarian rule in China. Comp. Political Stud. 2011, 44, 436–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K. Incremental Democracy and Good Governance (Zengliang Minzhu Yu Shanzhi); The Social Science Literature Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. The Study of Government Response Process (Zhengfu Huiying Guocheng Yanjiu); The Chinese Social Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Przeworski, A.; Stokes, S.; Manin, B. Democracy, Accountability, and Representation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Starling, G. Managing the Public Sector; Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, R. ‘Accountability’: An Ever-Expanding Concept? Public Adm. 2000, 78, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.A. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, K.W. The Nerves of Government; Models of Political Communication and Control; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Qiaoan, R.; Jessica, C.T. Responsive Authoritarianism in China—A Review of Responsiveness in Xi and Hu Administrations. J. Chin. Political Sci. 2019, 25, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distelhorst, G. Publicity-Driven Official Accountability in China: Qualitative and Experimental Evidence. MIT. 2012. Available online: http://web.mit.edu/polisci/people/gradstudents/papers/Distelhorst_PDA_0927.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Shirk, S.L. Changing Media, Changing China; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, J. Strong Society, Smart State: The Rise of Public Opinion in China’s Japan Policy; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- King, G.; Pan, J.; Roberts, M.E. How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2013, 107, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLisle, J.; Goldstein, A.; Yang, G. The Internet, Social Media, and a Changing China; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. Political contestation in Chinese digital spaces: Deepening the critical inquiry. China Inf. 2014, 28, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Meng, T. Selective responsiveness: Online public demands and government responsiveness in authoritarian China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 59, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pan, J.; Xu, Y. Sources of Authoritarian Responsiveness: A Field Experiment in China. Am. J. Political Sci. 2016, 60, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Meng, T.; Zhang, Q. From Internet to social safety net: The policy consequences of online participation in China. Governance 2019, 32, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The General Office of the State Council. The Circular of the General Office of the State Council on the First National Government Website Census.” 2015. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-12/15/content_10421.htm (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Easton, D. An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems. World Politics 1957, 9, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, G.; Coleman, J.S. The Politics of the Developing Areas; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. A Systems Analysis of Political Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Mellon, H. Deutsch re-visited: Government as communication and learning. Can. Public Adm. 2003, 46, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, K. Politics and Government: How People Decide Their Fate; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Lafferty, J.D. A Correlated Topic Model of Science. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2007, 1, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.E.; Stewart, B.M.; Tingley, D.; Lucas, C.; Leder-Luis, J.; Gadarian, S.K.; Albertson, B.; Rand, D.G. Structural topic models for open-ended survey responses. Am. J. Political Sci. 2014, 58, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.M.; Chana, Y.; Zhang, J.; van Witteloostuijn, A. Topic Modeling the Research-Practice Gap in Public Administration. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Meng, Q.; Ma, B. Policy Informatics: Big Data-Driven Public Policy Analysis (Zhengce Xinxi Xue: Da Shuju Qudong de Gonggong Zhengce Fenxi); Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C.; Nielsen, R.A.; Roberts, M.E.; Stewart, B.M.; Storer, A.; Tingley, D. Computer-Assisted Text Analysis for Comparative Politics. Political Anal. 2015, 23, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.E.; Stewart, B.M.; Airoldi, E.M. A Model of Text for Experimentation in the Social Sciences. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2016, 111, 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Nag, M.; Blei, D. Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of U.S. government arts funding. Poetics 2013, 41, 570–606. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich, T.; Lind, F.; Eberl, J.; Boomgaarden, H.J. Media Framing Dynamics of the ‘European Refugee Crisis’: A Comparative Topic Modelling Approach. J. Refug. Stud. 2019, 32, i172–i182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, C.; van Atteveldt, W.; Welbers, K. Quantitative analysis of large amounts of journalistic texts using topic modelling. Digit. Journal. 2016, 4, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, J.; Stewart, B. Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts. Political Anal. 2013, 21, 267–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimno, D.; Wallach, H.; Talley, E.; Leenders, M.; McCallum, A. Optimizing Semantic Coherence in Topic Models. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Edinburgh, UK, 27–31 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taddy, M.A. On Estimation and Selection for Topic Models. Artif. Intell. Stat. 2012, 22, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof, J.; Airoldi, E.M. Summarizing topical content with word frequency and exclusivity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Edinburgh, UK, 26 June–1 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Feng, S.; Tian, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, H. ERNIE 2.0: A Continual Pre-Training Framework for Language Understanding. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 8968–8975. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberthal, K. Governing China: From Revolution through Reform; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).