Evaluating Barriers to Supply Chain Resilience in Vietnamese SMEs: The Fuzzy VIKOR Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the critical barriers to the supply chain resilience of SMEs in Vietnam?

- RQ2: What is the ranking of these SCR barriers in the context of Vietnamese SMEs?

2. Literature Review

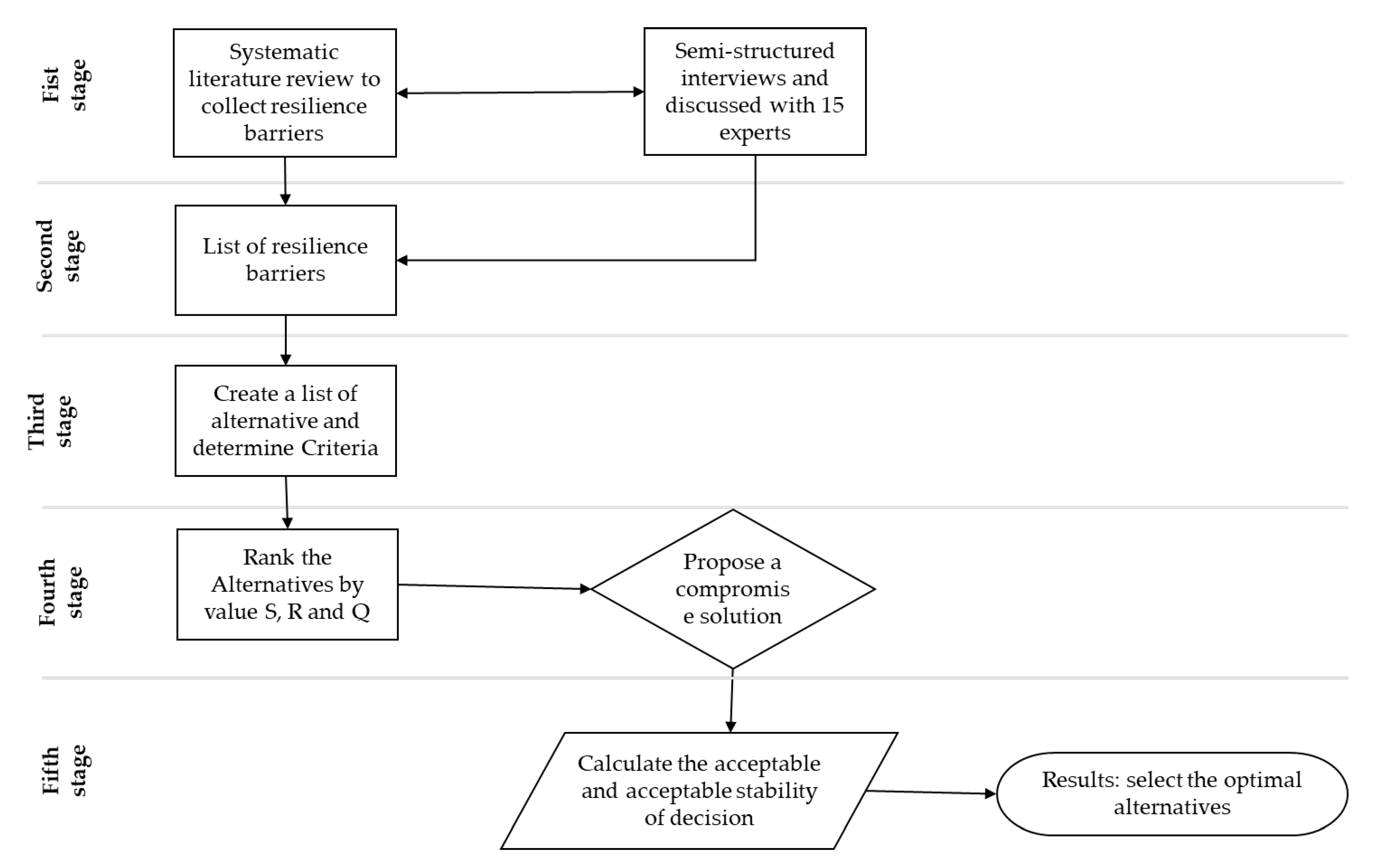

3. Research Methodology

3.1. The VIKOR Approach

- Step 1: Identify criteria—various barriers have been identified on the basis of the evaluation of supply chain professionals.

- Step 2: Normalized value formula— refers to the original value of alternatives and the dimension.

- Step 3: Determine the best and the worst for each criterion. From the problem’s decision matrix, determine the best and the worst values for all criterion functions, where is the positive ideal solution and is the negative ideal solution for the criteria.

- Step 4: Evaluate .

- Step 5: The values could be calculated to determine the ranking of criteria.

- (a)

- The fuzzy VIKOR technique considers the alternative that has the least amount of as the best alternative, and this is the alternative that could be selected as the compromise solution.

- (b)

- The alternatives can be prioritized by increasing , which is proposed as a compromise solution of alternative , which is best ranked by if two conditions are satisfied:

- In T1, acceptable advantage— is the second-best alternative, according to , where m is the number of alternatives.

- In T2, acceptable consistency in making decisions— must also rank option A as the best.

3.2. Data Collection

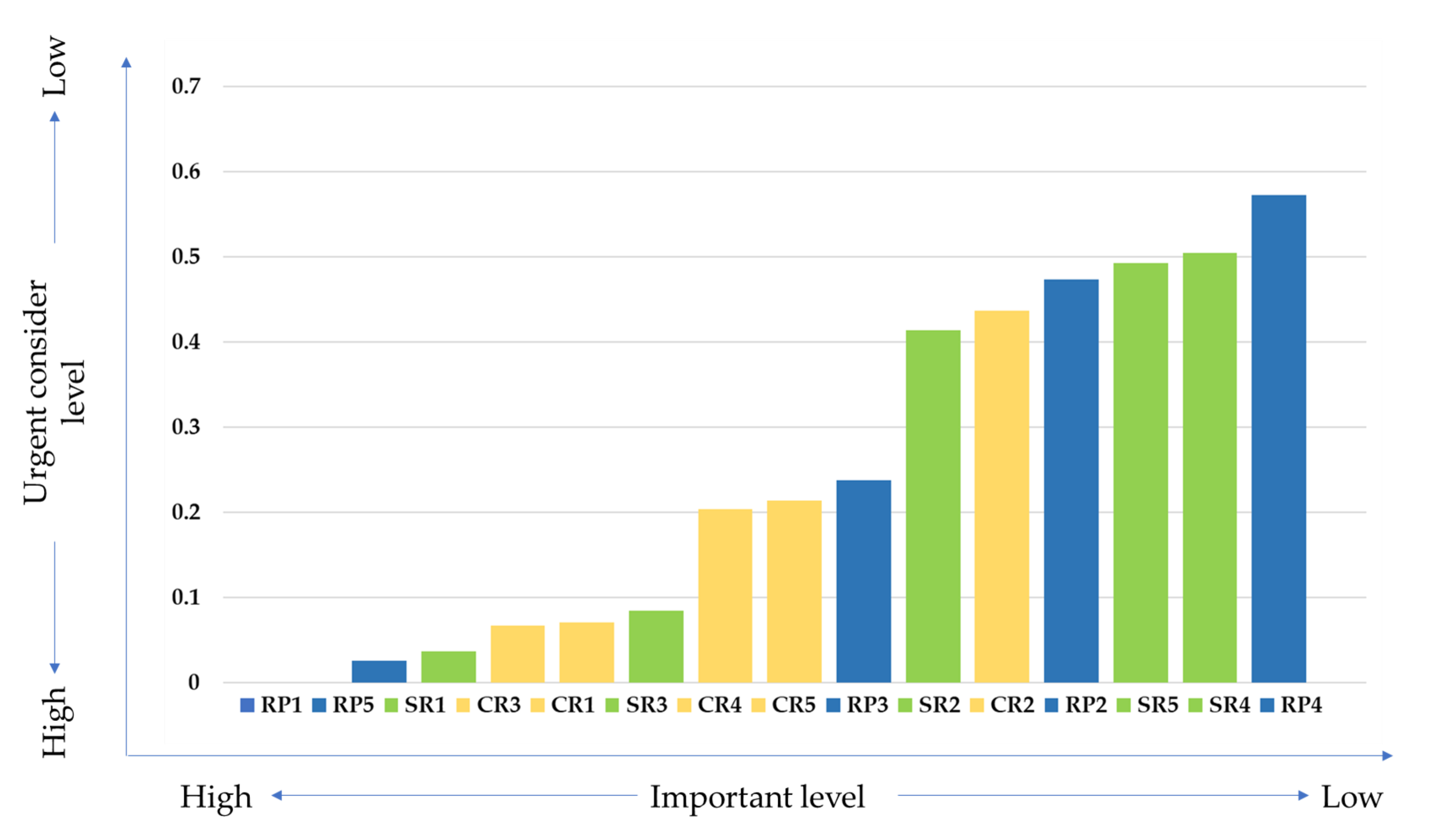

4. Result and Discussions

4.1. Identifying Supply Chain Resilience Barriers in Vietnamese SMEs

4.2. Discussions

5. Research Implications

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aman, S.; Seuring, S. Analysing Developing Countries Approaches of Supply Chain Resilience to COVID-19. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukamuhabwa, B.; Stevenson, M.; Busby, J. Supply Chain Resilience in a Developing Country Context: A Case Study on the Interconnectedness of Threats, Strategies and Outcomes. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 22, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Review of Quantitative Methods for Supply Chain Resilience Analysis. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 125, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Disruption Tails and Revival Policies: A Simulation Analysis of Supply Chain Design and Production-Ordering Systems in the Recovery and Post-Disruption Periods. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 127, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieske, A.; Birkel, H. Improving Supply Chain Resilience through Industry 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review under the Impressions of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 158, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Mohamed Ismail, M.W.; Tkachev, T. Bridging the Supply Chain Resilience Research and Practice Gaps: Pre and Post COVID-19 Perspectives. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2022, 15, 599–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chong, W.K.; Li, D. A Systematic Literature Review of the Capabilities and Performance Metrics of Supply Chain Resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4541–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Nagalingam, S.; Gurd, B. Building Resilience in SMEs of Perishable Product Supply Chains: Enablers, Barriers and Risks. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 1236–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Suleiman, N.; Khalid, N.; Tan, K.H.; Tseng, M.L.; Kumar, M. Supply Chain Resilience Reactive Strategies for Food SMEs in Coping to COVID-19 Crisis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, O.; Shaw, S.; Colicchia, C.; Kumar, V. A Systematic Literature Review of Supply Chain Resilience in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): A Call for Further Research. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 70, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Kumar, R. Strategic Issues in Supply Chain Management of Indian SMEs Due to Globalization: An Empirical Study. Benchmarking 2020, 27, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Measuring the Barriers to Resilience in Manufacturing Supply Chains Using Grey Clustering and VIKOR Approaches. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2018, 126, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Korchi, A. Survivability, Resilience and Sustainability of Supply Chains: The COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavian, E.; Alem Tabriz, A.; Zandieh, M.; Hamidizadeh, M.R. An Integrated Material-Financial Risk-Averse Resilient Supply Chain Model with a Real-World Application. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 161, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.P.S.; Huang, Y.-F.; Do, M.-H. Exploring the Challenges to Adopt Green Initiatives to Supply Chain Management for Manufacturing Industries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghshineh, B.; Carvalho, H. The Implications of Additive Manufacturing Technology Adoption for Supply Chain Resilience: A Systematic Search and Review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 247, 108387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Structural Dynamics and Resilience in Supply Chain Risk Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 265. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Linderman, K. Supply Network Resilience Learning: An Exploratory Data Analytics Study. Decis. Sci. 2022, 53, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.; Skouloudis, A.; Malesios, C.; Evangelinos, K. Bouncing Back from Extreme Weather Events: Some Preliminary Findings on Resilience Barriers Facing Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Trivedi, A.; Sharma, G.M.; Gharib, M.; Hameed, S.S. Analyzing Organizational Barriers towards Building Postpandemic Supply Chain Resilience in Indian MSMEs: A Grey-DEMATEL Approach. Benchmarking 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Seth, N.; Agarwal, A. Selecting Capabilities to Mitigate Supply Chain Resilience Barriers for an Industry 4.0 Manufacturing Company: An AHP-Fuzzy Topsis Approach. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 21, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Gupta, A.; Gunasekaran, A. Analysing the Interaction of Factors for Resilient Humanitarian Supply Chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 6809–6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghshineh, B.; Carvalho, H. Exploring the Interrelations between Additive Manufacturing Adoption Barriers and Supply Chain Vulnerabilities: The Case of an Original Equipment Manufacturer. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 1473–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dou, R.; Muddada, R.R.; Zhang, W. Management of a Holistic Supply Chain Network for Proactive Resilience: Theory and Case Study. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 125, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-F.; Chen, A.P.-S.; Do, M.-H.; Chung, J.-C. Assessing the Barriers of Green Innovation Implementation: Evidence from the Vietnamese Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.N.; Kumar, V.; Do, M.H. Prioritize the Key Parameters of Vietnamese Coffee Industries for Sustainability. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2020, 69, 1153–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Viability of Intertwined Supply Networks: Extending the Supply Chain Resilience Angles towards Survivability. A Position Paper Motivated by COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 2904–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.L.; Canavari, M.; Hingley, M. Resilience and Digitalization in Short Food Supply Chains: A Case Study Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, E.M.A.C.; Shen, G.Q.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Owusu, E.K. Critical Supply Chain Vulnerabilities Affecting Supply Chain Resilience of Industrialized Construction in Hong Kong. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 3041–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenstein, N.O.; Feise, E.; Hartmann, E.; Giunipero, L. Research on the Phenomenon of Supply Chain Resilience: A Systematic Review and Paths for Further Investigation. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Jain, R.K. Insights from Systematic Literature Review of Supply Chain Resilience and Disruption. Benchmarking 2022, 29, 2495–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Castro, L.F.; Solano-Charris, E.L. Integrating Resilience and Sustainability Criteria in the Supply Chain Network Design. A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Social and Environmental Risk Management in Resilient Supply Chains: A Periodical Study by the Grey-Verhulst Model. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 3748–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishodia, A.; Sharma, R.; Rajesh, R.; Munim, Z.H. Supply Chain Resilience: A Review, Conceptual Framework and Future Research. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, M.; Cagno, E.; Colicchia, C.; Sarkis, J. Integrating Sustainability and Resilience in the Supply Chain: A Systematic Literature Review and a Research Agenda. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 2858–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Mahfouz, A.; Arisha, A. Analysing Supply Chain Resilience: Integrating the Constructs in a Concept Mapping Framework via a Systematic Literature Review. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 22, 16–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Lean Resilience: AURA (Active Usage of Resilience Assets) Framework for Post-COVID-19 Supply Chain Management. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2022, 33, 1196–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Fosso Wamba, S.; Roubaud, D.; Foropon, C. Empirical Investigation of Data Analytics Capability and Organizational Flexibility as Complements to Supply Chain Resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekarian, M.; Parast, M.M. An Integrative Approach to Supply Chain Disruption Risk and Resilience Management: A Literature Review. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 24, 427–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, P.; Paul, S.K.; Azeem, A.; Chowdhury, P. Evaluating Supply Chain Collaboration Barriers in Smalland Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Mukherjee, A.A.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Srivastava, S.K. Supply Chain Management during and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic: Mitigation Strategies and Practical Lessons Learned. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 1125–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, N.; Scott, L.; Fan, J. Sustainable and Resilient Construction: Current Status and Future Challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyviou, M.; Croxton, K.L.; Knemeyer, A.M. Resilience of Medium-Sized Firms to Supply Chain Disruptions: The Role of Internal Social Capital. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mulhim, A.F. Smart Supply Chain and Firm Performance: The Role of Digital Technologies. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2021, 27, 1353–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Seth, N. Analysis of Supply Chain Resilience Barriers in Indian Automotive Company Using Total Interpretive Structural Modelling. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2021, 18, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.R.; Christopher, M.; Lago Da Silva, A. Achieving Supply Chain Resilience: The Role of Procurement. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, E.M.A.C.; Shen, G.Q.; Kumaraswamy, M. Supply Chain Resilience: Mapping the Knowledge Domains through a Bibliometric Approach. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2021, 11, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Paul, S.K.; Shukla, N.; Agarwal, R.; Taghikhah, F. Supply Chain Resilience Initiatives and Strategies: A Systematic Review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 170, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.H.; Huang, Y.F. Evaluation of Parameters for the Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Taiwanese Fresh-Fruit Sector. AIMS Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, K.; Sethi, A. An Empirical Investigation and Prioritizing Critical Barriers of Green Manufacturing Implementation Practices through VIKOR Approach. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 17, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Srivastava, M.K. A Grey-Based DEMATEL Model for Building Collaborative Resilience in Supply Chain. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 36, 1409–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stević, Ž.; Korucuk, S.; Karamaşa, Ç.; Demir, E.; Zavadskas, E.K. A Novel Integrated Fuzzy-Rough MCDM Model for Assessment of Barriers Related to Smart Logistics Applications and Demand Forecasting Method in the COVID-19 Period. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2022, 21, 1647–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.R.; Chen, S.M.; Rani, P. Multiattribute Decision Making Based on Fermatean Hesitant Fuzzy Sets and Modified VIKOR Method. Inf. Sci. 2022, 607, 1532–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, S.; Dash, R. An Empirical Comparison of TOPSIS and VIKOR for Ranking Decision-Making Models. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2022; Volume 286, pp. 429–437. ISBN 9789811698729. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.J.; Ali, M.I.; Kumam, P.; Kumam, W.; Aslam, M.; Alcantud, J.C.R. Improved Generalized Dissimilarity Measure-based VIKOR Method for Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 1807–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stević, Ž.; Subotić, M.; Softić, E.; Božić, B. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model for Evaluating Safety of Road Sections. J. Intell. Manag. Decis. 2022, 1, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Ali, S.M.; Moktadir, M.A.; Kusi-Sarpong, S. Evaluating Barriers to Implementing Green Supply Chain Management: An Example from an Emerging Economy. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 31, 673–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.H. Fuzzy VIKOR Method: A Case Study of the Hospital Service Evaluation in Taiwan. Inf. Sci. 2014, 271, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.K.; Datta, S.; Mahapatra, S.S. Evaluation and Selection of Resilient Suppliers in Fuzzy Environment: Exploration of Fuzzy-VIKOR. Benchmarking 2016, 23, 651–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, R.; Thakkar, J.J.; Jha, J.K. Evaluation of Risks in Foodgrains Supply Chain Using Failure Mode Effect Analysis and Fuzzy VIKOR. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2021, 38, 551–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabahi, S.; Parast, M.M. Firm Innovation and Supply Chain Resilience: A Dynamic Capability Perspective. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2020, 23, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Gölgeci, I. Where Is Supply Chain Resilience Research Heading? A Systematic and Co-Occurrence Analysis. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.H.d.O.; de Moraes, C.C.; da Silva, A.L.; Delai, I.; Chaudhuri, A.; Pereira, C.R. Does Resilience Reduce Food Waste? Analysis of Brazilian Supplier-Retailer Dyad. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A.; Fosso Wamba, S. Impacts of Epidemic Outbreaks on Supply Chains: Mapping a Research Agenda amid the COVID-19 Pandemic through a Structured Literature Review. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 319, 1159–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Low-Certainty-Need (LCN) Supply Chains: A New Perspective in Managing Disruption Risks and Resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 5119–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Industry | Academic | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6 | 40% | 3 | 20% | 9 | 60.0% |

| Female | 4 | 27% | 2 | 13% | 6 | 40.0% | |

| Age | Less than 40 | 1 | 7% | 1 | 7% | 2 | 13.33% |

| 41–50 years | 5 | 33% | 2 | 13% | 7 | 46.67% | |

| 51–60 years | 3 | 20% | 2 | 13% | 5 | 33.33% | |

| over 60 years | 1 | 7% | - | - | 1 | 6.67% | |

| Education | Bachelor degree | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Master’s degree | 8 | 53% | - | - | 8 | 53.33% | |

| Ph.D. degree | 2 | 13% | 5 | 33% | 7 | 46.67% | |

| Working experience | 10–15 years | 7 | 47% | 2 | 13% | 9 | 60.0% |

| over 15 years | 3 | 20% | 3 | 20% | 6 | 40.0% | |

| No | Code | Barriers | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience phase (RP) | ||||

| 1 | RP1 | Lack of financial resources | The lack of funds during a disruption, which makes it difficult to obtain urgent loans, will restrict the search for other methods to deliver products to clients on time. | [45,46] |

| 2 | RP2 | Lack of distribution channels | Transport infrastructure, including rivers, roads, and rail networks in the region of operation and supply chains, must be favorable and efficient to support SMEs. | [16] |

| 3 | RP3 | Lack of long-term vision and plan on practice of SCR | Directors focus on short-term gains and methods, not long-term strategies. | [12,46] |

| 4 | RP4 | Lack of IT integration | SMEs have demonstrated an inability to get real-time data on activity in the downstream supply chain. | [8] |

| 5 | RP5 | Lack of available alternatives for sources of supply | It is difficult for producers to locate alternate sources of supply, a difficulty that increases the possibility of unavailable raw materials and limited production, especially for SMEs. | [16,51] |

| Strategy resilience (SR) | ||||

| 6 | SR1 | Lack of skilled and competent workforce | For SME supply chain recovery to occur rapidly, educated professionals need to be available. | [22] |

| 7 | SR2 | Lack of ability to operational contingencies | In terms of a natural hazard or a pandemic, firms cannot immediately adapt to human, material, and financial changes. | [10] |

| 8 | SR3 | Noncommitment of top management | Senior management guides the organization during disruptions. Top management’s irresponsibility and lack of commitment might cause financial problems. | [45] |

| 9 | SR4 | Lack of agile capabilities | The organization’s business objectives need to be centered on locating the optimal combination of lean, agile, and resilient activities. | [20,33] |

| 10 | SR5 | Lack of relationship with vendors | Relationships with vendors are important for any supply chain, and partners must work well together. Shallow vendor relationships will impede supply chain recovery from risk and exacerbate resource availability issues. | [40,45] |

| Resilience competencies (CR) | ||||

| 11 | CR1 | Lack of collaboration across the supply chain | SMEs’ operations are interrupted, and there is no collaboration that will directly affect their operations. | [20,33,61] |

| 12 | CR2 | Lack of a diversification network | SMEs cannot quickly find a replacement source of raw material or input material. | [33] |

| 13 | CR3 | Lack of policy, guidance and support from government | When the environment is unstable, SMEs need government support and policies to overcome the crisis on time. | [19] |

| 14 | CR4 | Lack of transparency, collaboration, and trust in constructing a resilient system | Cooperating with suppliers, the firms often hide information and lack transparency, leading to information problems in the system. | [8,62] |

| 15 | CR5 | Capacity or inventory inflexibilities | Inflexibilities in inventories at various stages in the supply chain might become important barriers to resilience. | [12,46] |

| Linguistic Variables | Corresponding TFNs |

|---|---|

| Very low (VL) | (0.0; 0.1; 0.2) |

| Low(L) | (0.1; 0.2; 0.3) |

| Medium low (ML) | (0.2; 0.35; 0.5) |

| Medium (M) | (0.4; 0.5; 0.6) |

| Medium high (MH) | (0.5; 0.65; 0.8) |

| High (H) | (0.7; 0.8; 0.9) |

| Very high (VH) | (0.8; 0.9; 1.0) |

| Criteria 1 | Criteria 2 | Criteria 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP1 | 14.6667 | 17.9667 | 21.2667 | 14.2000 | 17.4333 | 20.6667 | 13.6667 | 16.7667 | 19.8667 |

| RP2 | 2.0667 | 3.2667 | 4.4667 | 10.6000 | 12.6333 | 14.6667 | 10.6000 | 12.6333 | 14.6667 |

| RP3 | 10.0000 | 11.8667 | 13.7333 | 10.8667 | 12.9000 | 14.9333 | 10.6000 | 12.6333 | 14.6667 |

| RP4 | 11.4000 | 13.7667 | 16.1333 | 1.7333 | 2.9667 | 4.2000 | 1.7333 | 2.9667 | 4.2000 |

| RP5 | 14.2667 | 17.2667 | 20.2667 | 13.8667 | 16.9667 | 20.0667 | 13.4000 | 16.5000 | 19.6000 |

| SR1 | 14.6667 | 17.8333 | 21.0000 | 14.0000 | 16.9667 | 19.9333 | 13.1333 | 15.6667 | 18.2000 |

| SR2 | 9.1333 | 10.7667 | 12.4000 | 5.6667 | 6.8333 | 8.0000 | 9.4000 | 11.0333 | 12.6667 |

| SR3 | 12.7000 | 15.2167 | 17.7333 | 13.7333 | 16.7333 | 19.7333 | 13.3333 | 16.1667 | 19.0000 |

| SR4 | 0.8000 | 1.3667 | 1.9333 | 11.6000 | 13.7667 | 15.9333 | 11.8000 | 14.1333 | 16.4667 |

| SR5 | 5.3333 | 6.5333 | 7.7333 | 5.3333 | 6.5333 | 7.7333 | 5.3333 | 6.5333 | 7.7333 |

| CR1 | 13.8667 | 17.0667 | 20.2667 | 12.7333 | 15.4333 | 18.1333 | 13.0000 | 15.9333 | 18.8667 |

| CR2 | 10.1333 | 11.9333 | 13.7333 | 5.6667 | 6.8333 | 8.0000 | 6.0000 | 7.2667 | 8.5333 |

| CR3 | 13.2000 | 15.9333 | 18.6667 | 14.2000 | 17.0667 | 19.9333 | 12.8000 | 15.5667 | 18.3333 |

| CR4 | 11.9000 | 14.2167 | 16.5333 | 10.6000 | 12.6333 | 14.6667 | 10.6000 | 12.6333 | 14.6667 |

| CR5 | 10.7667 | 12.8167 | 14.8667 | 11.0667 | 13.1000 | 15.1333 | 10.3333 | 12.3000 | 14.2667 |

| Criteria 1 | Criteria 2 | Criteria 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.667 | 17.967 | 21.267 | 14.200 | 17.433 | 20.667 | 13.667 | 16.767 | 19.867 | |

| 0.800 | 1.367 | 1.933 | 1.733 | 2.967 | 4.200 | 1.733 | 2.967 | 4.200 | |

| Barriers | Si | Ri | Qi | Rank (Qi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP1 | −0.0168 | −0.0034 | 0.0000 | 1 |

| RP2 | 0.3869 | 0.2357 | 0.4737 | 12 |

| RP3 | 0.2416 | 0.0951 | 0.2372 | 9 |

| RP4 | 0.5642 | 0.2508 | 0.5727 | 15 |

| RP5 | 0.0081 | 0.0080 | 0.0252 | 2 |

| SR1 | 0.0147 | 0.0150 | 0.0367 | 3 |

| SR2 | 0.3970 | 0.1827 | 0.4141 | 10 |

| SR3 | 0.0525 | 0.0401 | 0.0842 | 6 |

| SR4 | 0.3704 | 0.2672 | 0.5043 | 14 |

| SR5 | 0.5547 | 0.1880 | 0.4924 | 13 |

| CR1 | 0.0491 | 0.0300 | 0.0705 | 5 |

| CR2 | 0.4475 | 0.1827 | 0.4371 | 11 |

| CR3 | 0.0460 | 0.0282 | 0.0669 | 4 |

| CR4 | 0.2076 | 0.0799 | 0.2032 | 7 |

| CR5 | 0.2286 | 0.0808 | 0.2139 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phan, V.-D.-V.; Huang, Y.-F.; Hoang, T.-T.; Do, M.-H. Evaluating Barriers to Supply Chain Resilience in Vietnamese SMEs: The Fuzzy VIKOR Approach. Systems 2023, 11, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030121

Phan V-D-V, Huang Y-F, Hoang T-T, Do M-H. Evaluating Barriers to Supply Chain Resilience in Vietnamese SMEs: The Fuzzy VIKOR Approach. Systems. 2023; 11(3):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030121

Chicago/Turabian StylePhan, Vu-Dung-Van, Yung-Fu Huang, Thi-Them Hoang, and Manh-Hoang Do. 2023. "Evaluating Barriers to Supply Chain Resilience in Vietnamese SMEs: The Fuzzy VIKOR Approach" Systems 11, no. 3: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030121

APA StylePhan, V.-D.-V., Huang, Y.-F., Hoang, T.-T., & Do, M.-H. (2023). Evaluating Barriers to Supply Chain Resilience in Vietnamese SMEs: The Fuzzy VIKOR Approach. Systems, 11(3), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030121