Role of Information Systems in Effective Management of Human Resources during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Objectives

1.2. Research Purpose and Rationale

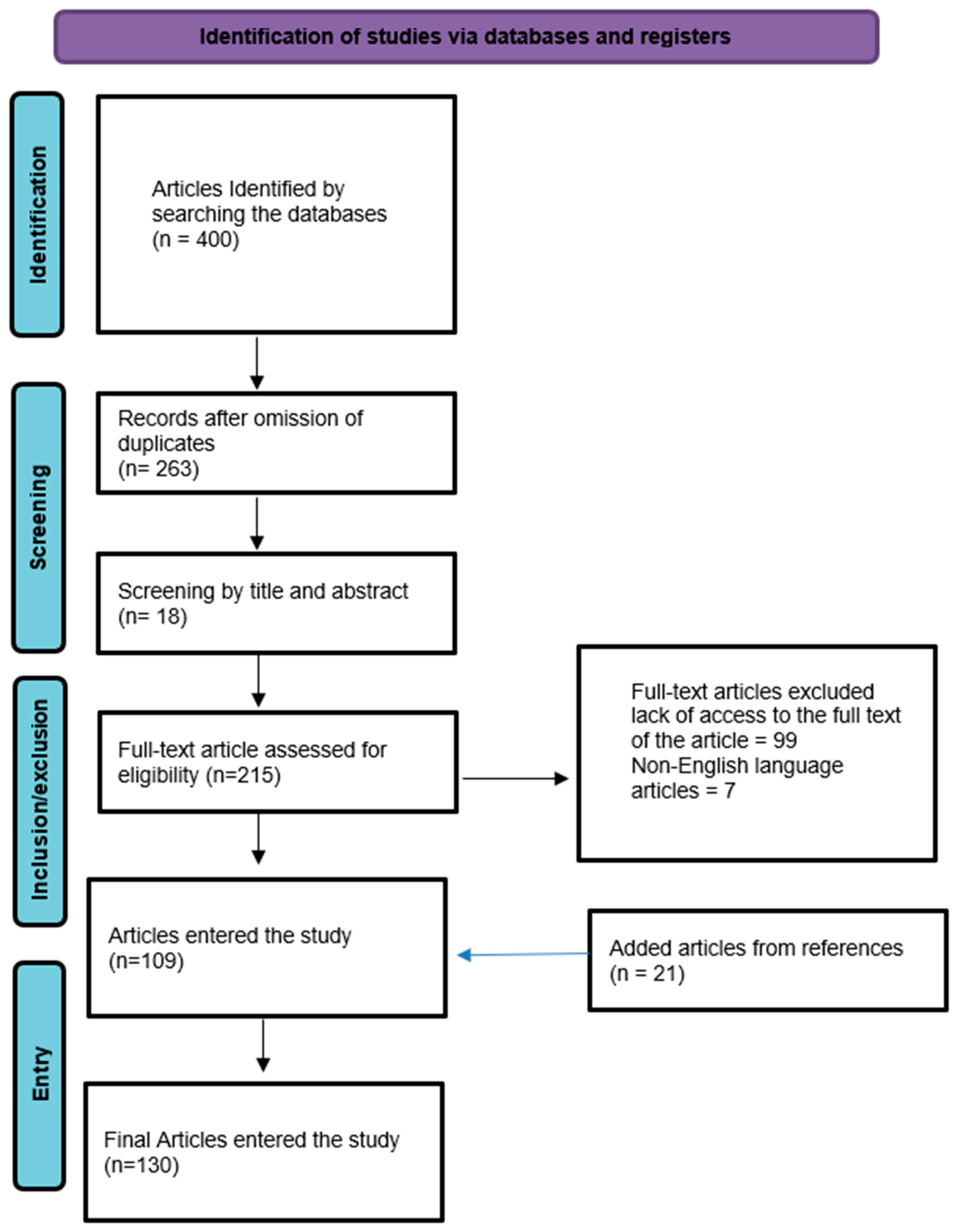

2. Research Methodology

- Eligibility criteria

- Inclusion: By utilizing the Boolean operators (‘OR’ and ‘AND’), only the keywords that are related to the research within HR strategies—namely, planning and recruitment, performance appraisal, training and development, compensation, benefits, personal supports and employee well-being, providing a comprehensive understanding of these topics in organizational settings are used.

- Exclusion: Non-English language-based articles, titles and abstract with HRM strategies but without keywords such as information systems, IT tools, COVID-19, and HR practices and without inclusion keywords are omitted and excluded.

- Information sources

- Databases and registers: EBSCO (Elton B. Stephens Company), JSTOR (Journal Storage), Scopus, Web of Science, Australian Business Dean Council and ABS journal database.

- Filters and limits: Publication date: 2019–2021 (during COVID-19); language: English; text: full text (by using the Boolean condition to filter links “FindIt@XYZ”); title: subject area, topic, category and important keywords; access: full accessible texts; language bias: non-English language.

- Search strategy

- Screening and eligibility: Intervention of HRM practices during COVID-19 and usage of IT tools and Information Systems; comparison other pre-COVID-19 and post COVID-19 materials; article retained if only abstract is available; meta-analysis (PRISMA) by including keyword of “non-English language”-based articles and not relevant to HRM strategies during COVID-19 using IT tools and Information Systems.

- Bias assessment and study risks

3. Role of Information Technology-Based Tools in Executing Various Functions of Human Resource Management

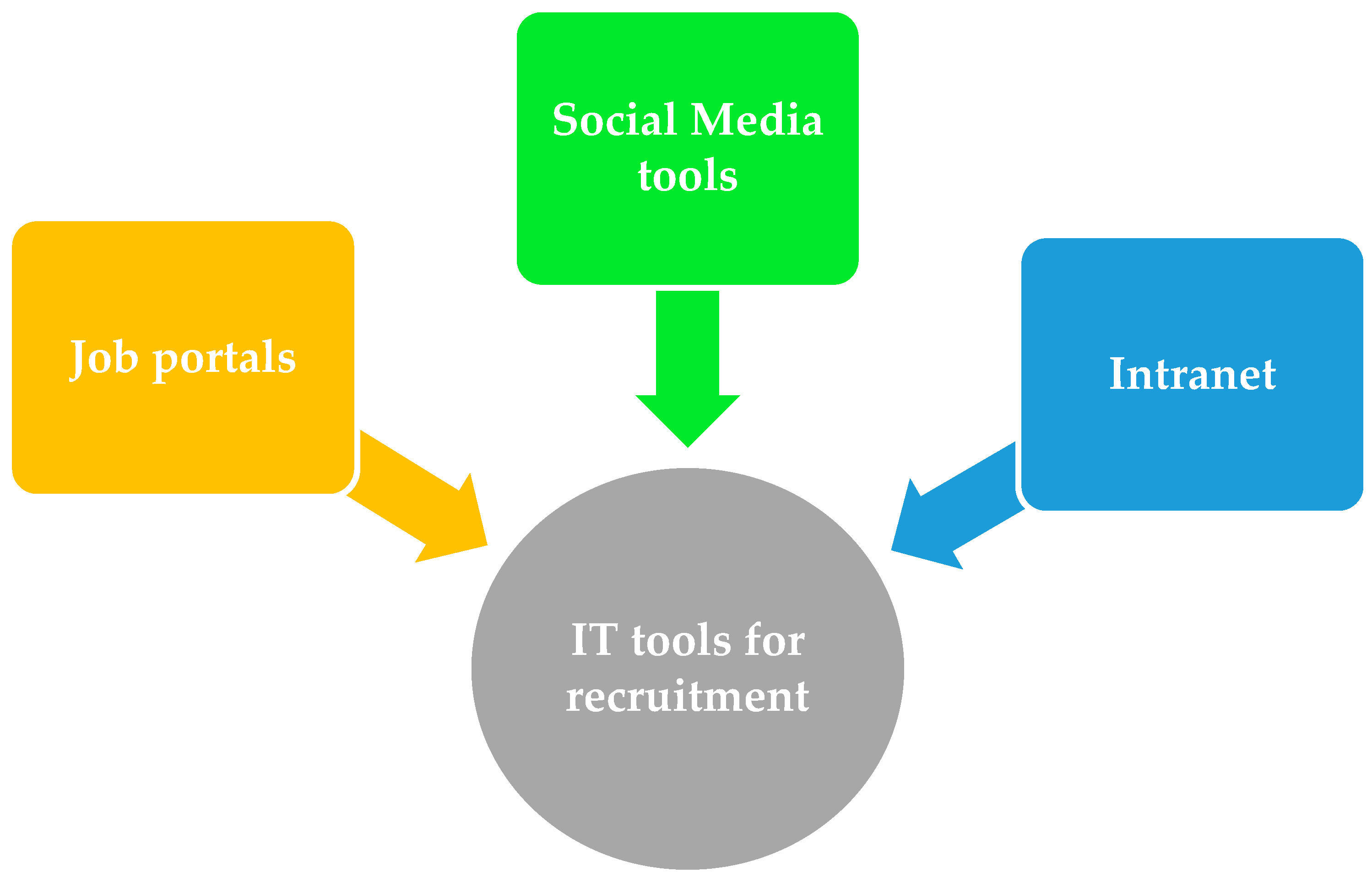

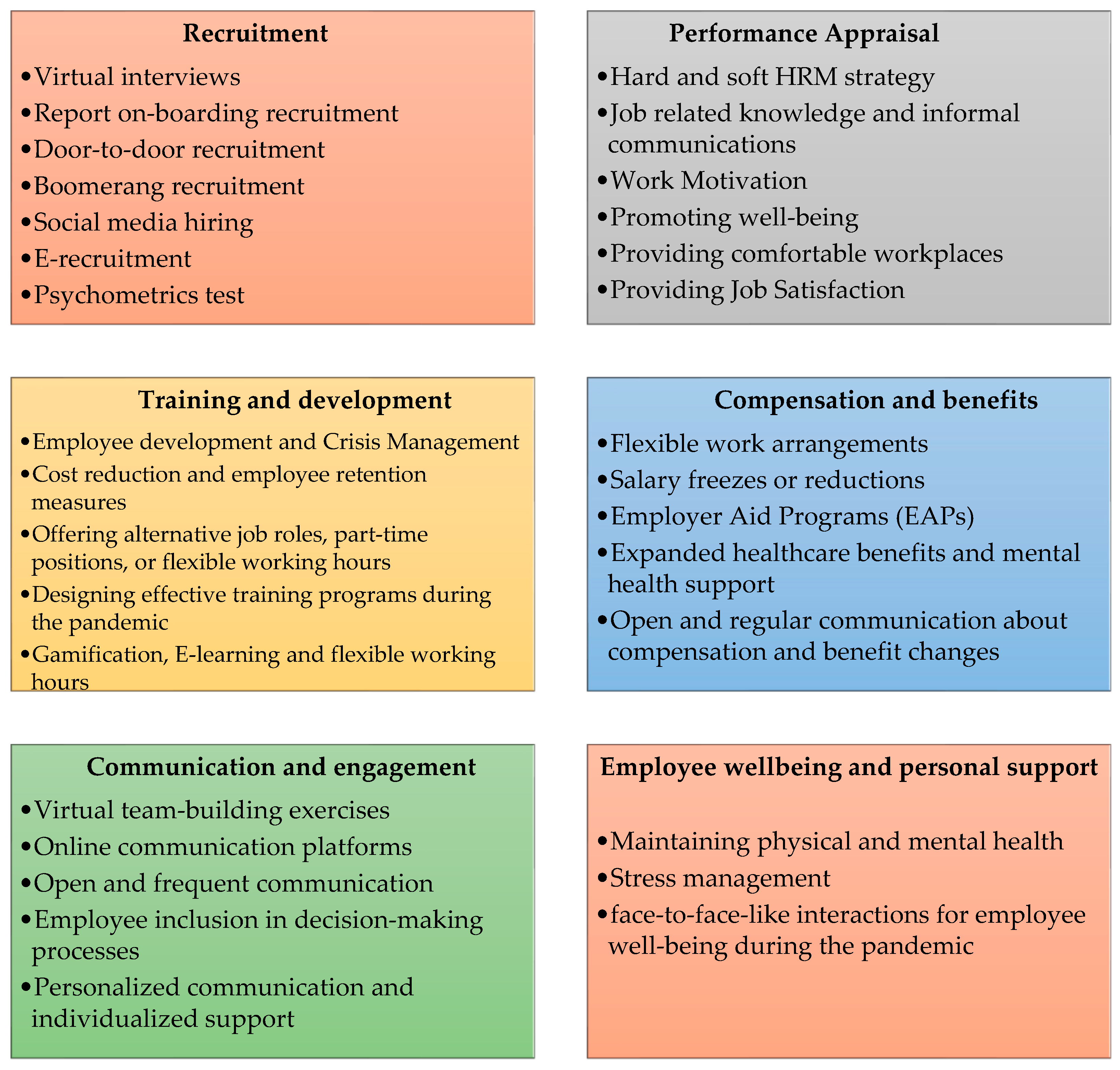

3.1. HR Strategies Used in Planning and Recruitment during COVID-19 Pandemic

3.2. HR Strategies Used in Performance Appraisal during COVID-19 Pandemic

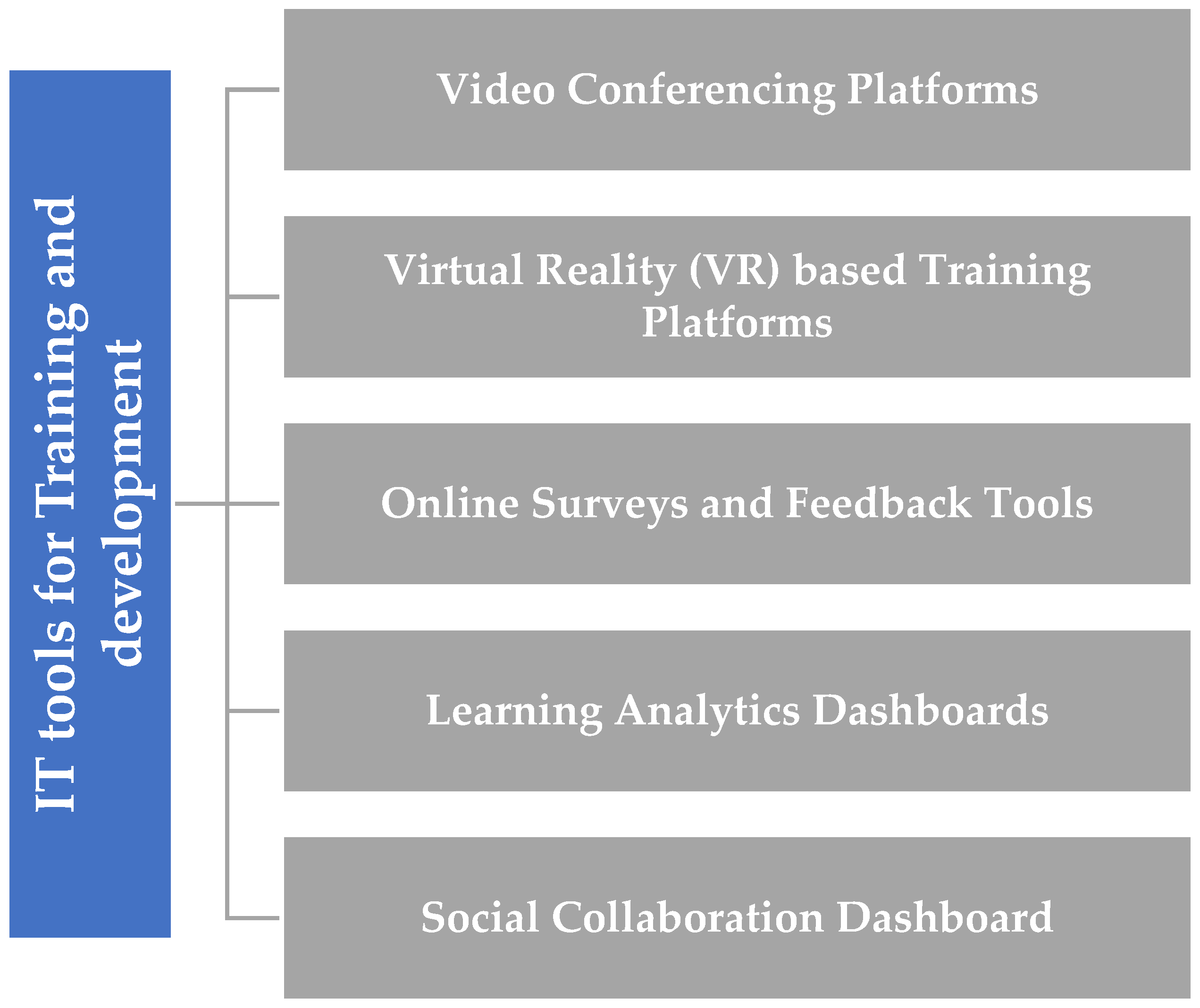

3.3. HR Strategies Used in Training and Development during COVID-19 Pandemic

3.4. HR Strategies Used in Compensation and Benefits during COVID-19 Pandemic

3.5. HR Strategies Used in Employee Engagement and Communication during COVID-19 Pandemic

3.6. HR Strategies Used in Employee Well-Being and Personal Support during COVID-19 Pandemic

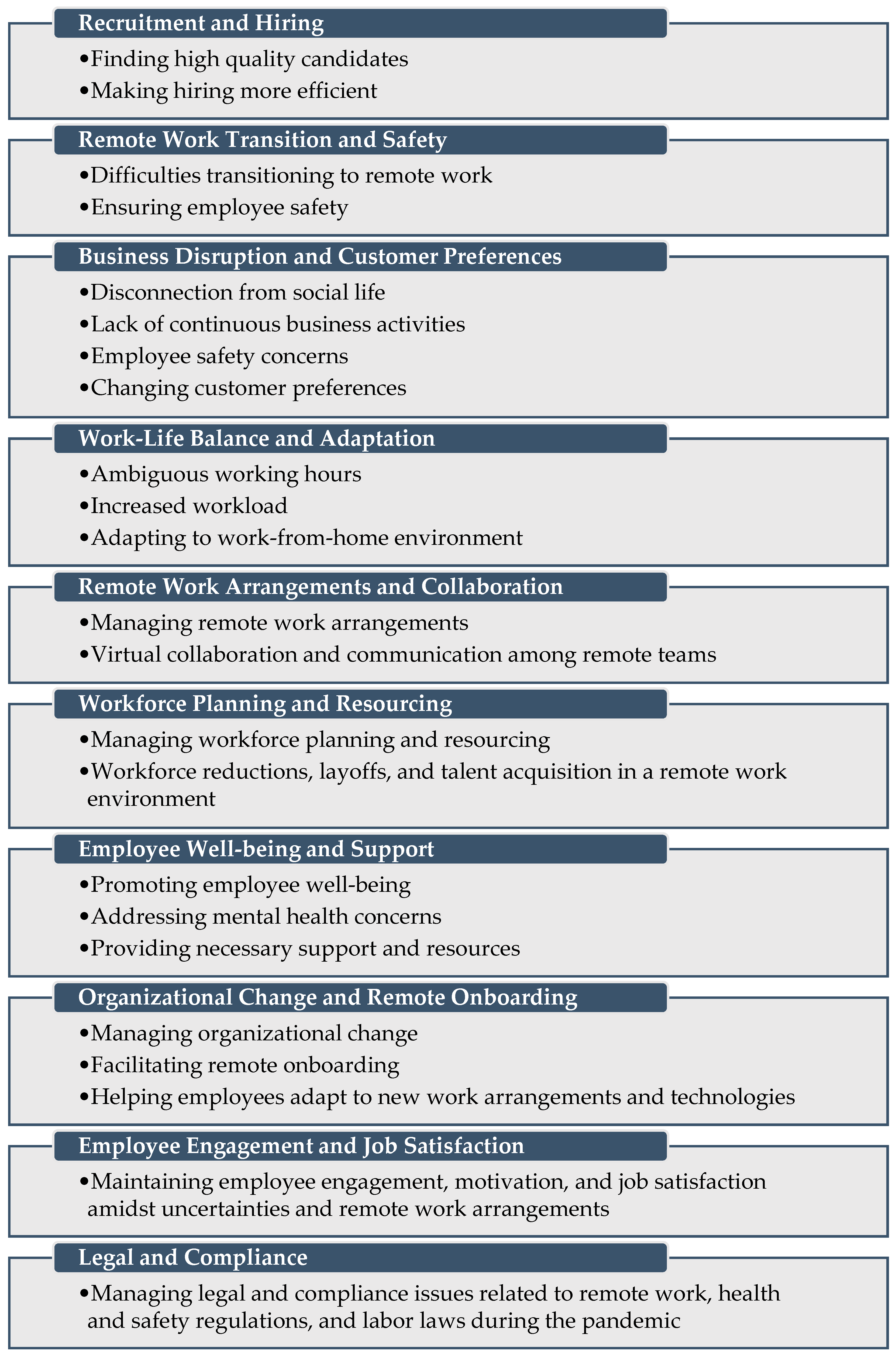

3.7. Challenges Faced by HR during COVID-19 Pandemic

3.8. Research Gap

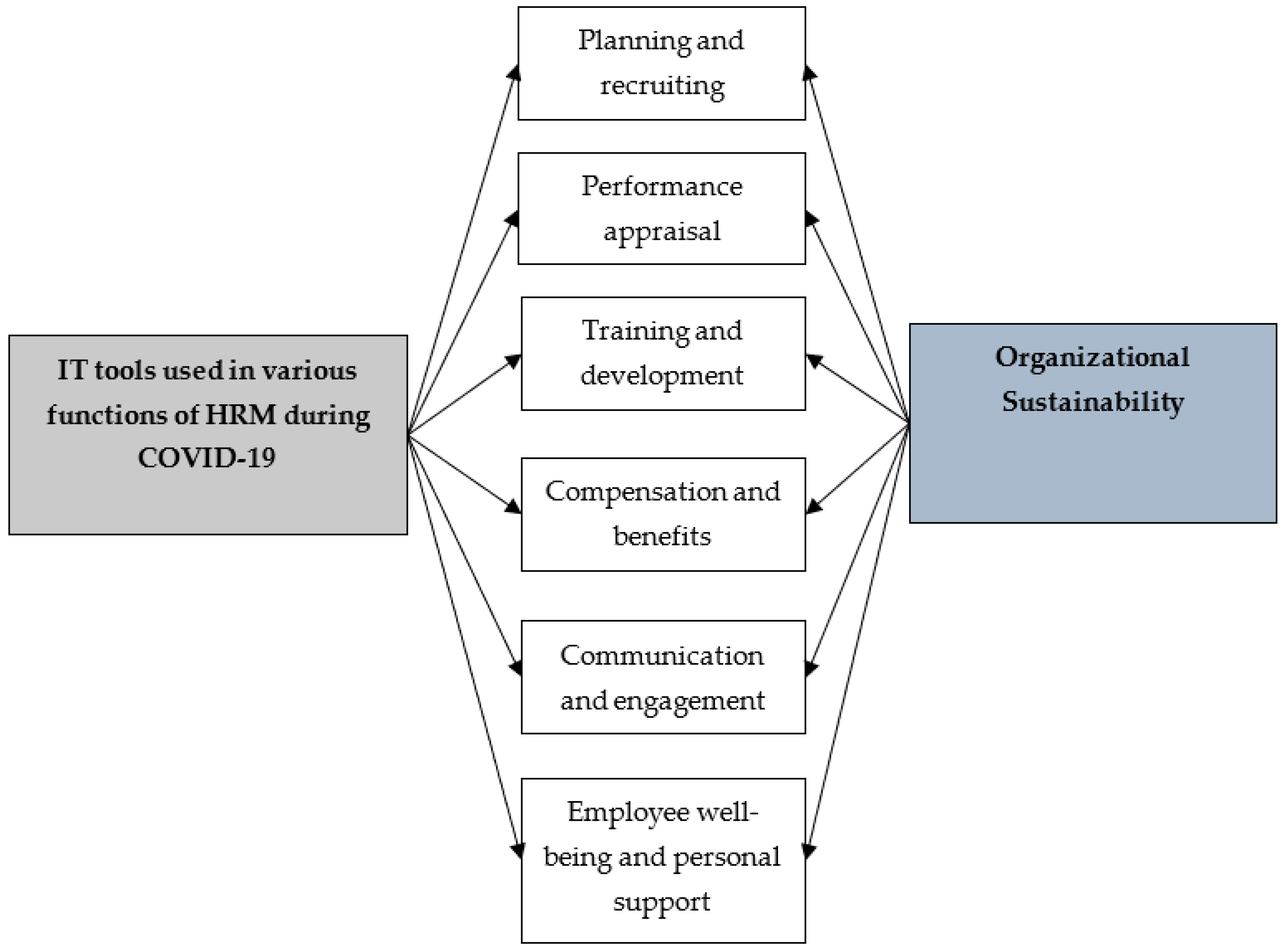

3.9. A Theoretical Framework on the Role of HR Strategies in Maintaining Sustainability

- P1: IT tools adopted by HR managers for planning and recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic helped organizations attain organizational sustainability.

- P2: IT tools adopted by HR managers for performance appraisal during the COVID-19 pandemic helped organizations attain organizational sustainability.

- P3: IT tools adopted by HR managers for training and development during the COVID-19 pandemic helped organizations attain organizational sustainability.

- P4: IT tools adopted by HR managers for offering compensation and benefits to employees during the COVID-19 pandemic helped organizations attain organizational sustainability.

- P5: IT tools adopted by HR managers for offering communication and engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic helped organizations attain organizational sustainability.

- P6: IT tools adopted by HR managers for employee well-being and personal support during the COVID-19 pandemic helped organizations attain organizational sustainability.

4. Discussion

Comparative Analysis

- −

- Pre-COVID-19: For employees to be satisfied with their work, it was essential to have appropriate HRM practices in place [110]. Job satisfaction and performance were positively related to HRM practices [111,112,113]. It was demonstrated that HRM strategies that promoted employee performance were effective [99] and as long as employees were engaged and performing well, they were more likely to stay with the company. The effectiveness of HRM practices enhanced organizational commitment, i.e., identifying, assuming, and fulfilling responsibilities, and avoiding quitting the company [114,115,116]. Employee behavior was positively impacted by organizational commitment [117,118]. Employees who were committed to achieving organizational goals were more likely to act in a positive manner [119,120]. In numerous studies [121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129], commitment to the organization was positively correlated with job performance.

- −

- During COVID-19: The HR strategies adapted during COVID-19 by the organizations for effective human resource management was studied by several authors. The authors of [130] examined the crisis management, and 6Cs concept (compensation, caring culture, creativity, collaboration and coordination, clean/hygiene and communication) was adapted as an HR practice during COVID-19. The study by [131] concluded that adapting to new changes during the pandemic initially caused a denial of changes that affected the physical and psychological stability of employees. However, with the assistance of IS and IT tools, employees accepted the changes which, in turn, increased their productivity and performance. The authors of [132] examined and concluded that good HRM and HR practices (adopting IT tools and IS) positively impacted the organizational sustainability globally, whereas the bad HRM and HR practices failed to sustain. The authors of [133] insisted that COVID-19 altered the organizational functions and operations. According to the author, the challenges faced by the HR personnel in staffing, training and development, monitoring and guiding, performance appraisals, benefits, compensation, health and safety management (well-being), employee–employer relationships and recruiting and planning for virtual teams affected the organizational sustainability. However, it was concluded that positive HRM strategies during COVID-19 increased the organizational productivity, which had an indirect association with the employees’ performances, motivation, mental well-being, productivity and satisfaction.

- −

- Post COVID-19: Several authors like [44,134,135,136,137] studied the practice of incorporating more IT tools and ISs by the HR as a part of the working culture post-COVID-19. The conclusions from the studies revealed that employees’ performances increased when they used IT tools and ISs in remote work settings. Hence, the authors insisted that removing the usage of IT tools and ISs post COVID-19 will decrease the productivity and performance. Hence, it is recommended and argued among the researchers that implementing an IT tools-based working culture and the usage of ISs in regular working mode as well will motivate employees and result in organizational sustainability.

- −

- Role of HR during COVID-19: In order to help organizations overcome the obstacles posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and develop strategies to achieve their goals, human resource management is essential. This entails putting employee well-being first while striving to meet the organization’s objectives for the COVID-19 pandemic [138]. HR professionals were responsible for motivating employees and providing them with adequate support during the abrupt transition in their work mode [139]. Numerous studies have emphasized the significance of organizational support during times of crisis [140]. It is clear that ensuring the internal consistency of these support measures is crucial not only in how they relate to each other when implemented during a crisis but also in alignment with established practices from the past, as this alignment can enhance their positive effects on employees.

5. Conclusions

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Risley, C. Maintaining performance and employee engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Libr. Adm. 2020, 60, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoosefi Lebni, J.; Abbas, J.; Moradi, F.; Salahshoor, M.R.; Chaboksavar, F.; Irandoost, S.F.; Nezhaddadgar, N.; Ziapour, A. How the COVID-19 pandemic affected economic, social, political, and cultural factors: A lesson from Iran. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanana, N.; Sangeeta. Employee engagement practices during COVID-19 lockdown. J. Public Aff. 2020, 21, e2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leon, V. Human Resource Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph.D. Thesis, California State University, Northridge, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roggeveen, S.; Chen, S.-W.; Harmony, C.R.; Ma, Z.; Qiao, P. The adaption of post COVID-19 in IHRM to mitigate changes in employee welfare affecting cross-cultural employment. IETI Trans. Econ. Manag. 2020, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, R.S. Redefining the Role of HRM in Sustainability in COVID 19 Pandemic & Future: A Conceptual & Strategic Framework. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Sustainable Development: A Roadmap to an Equitable Planet (GDGU ICON-2022) Organized by the School of Management, GD Goenka University, Gurgaon, India, 20–21 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouche, S. COVID-19 and employees’ mental health: Stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Res. 2020, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Ensuring Fair Recruitment during the COVID-19 Pandemic; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M. Recruitment: An Introduction. 2020. Available online: https://www.cipd.ie/news-resources/practical-guidance/factsheets/recruitment#7034 (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Raveendra, P.V.; Satish, Y.M. Boomerang hiring: Strategy for sustainable development in COVID-19 era. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2022, 41, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, D.M.A.; Ptel, A. Social Posting in COVID-19 Recruiting Era—Milestone HR Strategy Augmenting Social Media Recruitment. DogoRangsang Res. J. 2020, 10, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Amaliyah; Cahyo, F.R.D.; Reindrawati, D.Y. The Hybrid System for Recruitment and Selection during COVID-19 Pandemic. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. Int. J. 2022, 14, 1595–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Husna, J.; Sadiqin, S.; Muhaimin, Y.; Fitriyana, F.; Wahdiyah, R. The Effectiveness of E-Recruitment Method through Social Media (Case Study at Pt Es Teh Indonesia Makmur—West Java). E3S Web Conf. 2021, 317, 05012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddharthan, R.; Palani, A. A Study on E Recruitment during Pandemic at ALLSEC Technologies. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2022, 10, a571–a575. [Google Scholar]

- Karasik, J. Door-to-door recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned from a population based, longitudinal cohort study in North Carolina, USA. Res. Sq. 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, L. Why Is Human Resources Important?—Breathe HR, 22 June 2021. Available online: https://www.breathehr.com/en-gb/blog/topic/business-process/why-is-human-resources-important (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- TalentLyft. What Is E-Recruitment. 2022. Available online: https://www.talentlyft.com/en/resources/what-is-e-recruitment (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Jezzini, S.M.M. An Investigation into the Impact of the Pandemic on Recruitment Methods from a Recruiters’ Perspective. Master’s Thesis, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bieńkowska, A.; Koszela, A.; Sałamacha, A.; Tworek, K. COVID-19 oriented HRM strategies influence on job and organizational performance through job-related attitudes. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovmasyan, G.; Minasyan, D. The Impact of Motivation on Work Efficiency for Both Employers and Employees also during COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Study from Armenia. Bus. Ethics Leadersh. 2020, 4, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolor, C.W.; Solikhah, S.; Fidhyallah, N.F.; Lestari, D.P. Effectiveness of E-Training, E-Leadership, and Work Life Balance on Employee Performance during COVID-19. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo-Thanh, T.; Vu, T.V.; Nguyen, N.P.; Nguyen, D.V.; Zaman, M.; Chi, H. How does hotel employees’ satisfaction with the organization’s COVID-19 responses affect job insecurity and job performance? J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 907–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, N.N.; Nowlin, E.L.; Walker, D.; Anaza, N.A. Alone on an island: A mixed-methods investigation of salesperson social isolation in general and in times of a pandemic. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 96, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapta, I.K.S.; Muafi, M.; Setini, N.M. The Role of Technology, Organizational Culture, and Job Satisfaction in Improving Employee Performance during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 495–505. [Google Scholar]

- Granziera, H.; Perera, H. Relations among Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs, Engagement, and Work Satisfaction: A Social Cognitive View. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 58, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.; Nguyen, P.T.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Rafferty, A.; Schwarz, G. Unraveling the What and How of Organizational Communication to Employees during COVID-19 Pandemic: Adopting an Attributional Lens. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2020, 56, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Waheed, A. Employee Development and Its Affect on Employee Performance: A Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 224–229. [Google Scholar]

- Antonacopoulou, E.P. Employee development through self-development in three retail banks. Pers. Rev. 2000, 29, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M.; Sandelands, L.E.; Dutton, J.E. Threat Rigidity Effects in Organizational Behavior: A Multilevel Analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardarlıer, P. Strategic Approach to Human Resources Management during Crisis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.A. Issues in Pakistan’s Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wynen, J.; Op De Beeck, S. The impact of the financial and economic crisis on turnover intention in the U.S. federal government. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczyk, K. Changes in the approach to employee development in organisations as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 46, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S. COVID-19 crisis and challenges for human resource management. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2023, 3, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- AL-Rawahi, M.H. A Research Study on the Impact of Training and Development on Employee Performance during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Manag. Stud. Res. 2022, 10, 1007001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, J.; Skyes, J. Special Issue Commentary: Digital Game and Play Activity in L2 Teaching and Learning. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2014, 18, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, S.A.; Trevisan, L.N.; Veloso, E.F.R.; Treff, M.A. Gamification in training and development processes: Perception on effectiveness and results. Gamification Train. Dev. 2021, 28, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Escamez, F.A.; Roldán-Tapia, M.D. Gamification as Online Teaching Strategy during COVID-19: A Mini-Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HR Asia. The Importance of Gamification during a Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://hr.asia/featured/the-importance-of-gamification-during-a-pandemic/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Kumar, A.; Pujari, P.; Thatta, S.; Manocha, S. Gamification as a Sustainable Tool for HR Managers. Acta Univ. Bohem. Merid. 2021, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.H.B.; Arafat, S.; Islam, I.; Nur, J.M.E.H.; Rahman, S.; Khan, S.I.; Alam, M.S. The emergence of e-learning and online-based training during the COVID-19 crisis: An exploratory investigation from Bangladesh. Manag. Matters 2022, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, T.; Doepke, M.; Olmstead-Rumsey, J.; Tertilt, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality; NBER Working Paper No. 26947; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A.; Ferrer, J.; Andersen, M.; Zhang, Y. Human resource management in times of crisis: What have we learnt from the recent pandemic? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 2857–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Ding, Y. Health inequality and COVID-19: A causal link? Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 269, 113358. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, S.; Rosen, B. Compensation and Benefits for Remote Workers during COVID-19: How to Address New Risks? Compens. Benefits Rev. 2020, 52, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zha, J. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on organizations: Rethinking the design of HRM practices. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 31, 101987. [Google Scholar]

- Malynovska, Y.; Bashynska, I.; Cichoń, D.; Malynovskyy, Y.; Sala, D. Enhancing the Activity of Employees of the Communication Department of an Energy Sector Company. Energies 2022, 15, 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, M.; Ingusci, E.; Cortese, C.G.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Molino, M.; Signore, F.; Russo, V. Does the End Justify the Means? The Role of Organizational Communication among Work-from-Home Employees during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, D.K.; Kuhn, T.R. Organizational Communication: A Critical Introduction; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber, G.M. Organizational Communication; Book News, Inc.: Portland, OR, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, D.; Daft, R. Management; Cengage Learning Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, J. The Business Communication Handbook; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R.L. The Taking of Organizational Roles. In The Social Psychology of Organizations; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1978; pp. 185–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ramus, C.A. Organizational support for employees: Encouraging creative ideas for environmental sustainability. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, M.W.; Hanley-Maxwell, C.; Capper, C.A. Spirituality? It’s the core of my leadership: Empowering leadership in an inclusive elementary school. Educ. Adm. Q. 1999, 35, 203–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantz, C.R.; Pepper, G.L. Understanding Organizations: Interpreting Organizational Communication Cultures; University of South Carolina Press: Columbia, SC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, M.; Hlouskova, L.; Novotny, P.; Vaclavikova, E.; Zounek, J. School Culture as an Object of Research. Online Submiss. 2005, 5, 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Dee, J.; Leisyte, L. Knowledge sharing and organizational change in higher education. Learn. Organ. 2017, 24, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.N.; Dietz, G.; Thornhill, A. Trust and distrust: Polar opposites, or independent but co-existing? Organ. Stud. 2014, 35, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D. Attitudes Toward Organizational Change among Public Middle Managers. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 44, 70–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiest, S.; Segers, J.; van Witteloostuijn, A. Climate, communication and participation impacting commitment to change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2015, 28, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Král, P.; Králová, V. Approaches to changing organizational structure: The effect of drivers and communication. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5169–5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Cameron, A.; Ensink, F.; Hazarika, J.; Attir, R.; Ezzedine, R.; Shekhar, V. Factors that impact the success of an organizational change: A case study analysis. Ind. Commer. Train. 2017, 49, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.; Fieldman, G.; Altman, Y. E-mail at work: A cause for concern? The implications of the new communication technologies for health, wellbeing, and productivity at work. J. Organ. Transform. Soc. Chang. 2008, 5, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler, M.J.; Mengis, J. The concept of information overload: A review of literature from organization science, accounting, marketing, MIS, and related disciplines. In Kommunikation im Wandel; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2004; pp. 271–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hargie, O.; Tourish, D.; Wilson, N. Communication audits and the effects of increased information: A follow-up study. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2002, 39, 414–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, W.; Yuan, B. From the perspective of human resource management: A review of corporate countermeasures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, N.; Nunes, C.; Nunes, M. Employee engagement and the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of HRM practices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.; Fisher, C.; Morris, A.; Vidal-Brown, D. HR’s response to COVID-19: The influence of employee voice on furlough opinions and organizational reputation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Xu, W.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L.; Fan, J.; Chen, J. Mental health status of students’ parents during COVID-19 pandemic and its influence factors. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crapun, A.; Llorens, F.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employees’ work engagement and emotional exhaustion: The role of teleworking intensity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, C.G.; Greaves, L.M.; Satherley, N.; Wilson, M.S.; Overall, N.C.; Lee, C.H.; Milojev, P.; Bulbulia, J.; Osborne, D.; Milfont, T.L.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Nationwide Lockdown on Trust, Attitudes Toward Government, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.E.; Bhagat, R.S. Organizational Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance: Where Do We Go from Here? J. Manag. 1992, 18, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Friedman, M.J.; Watson, P.J. 60,000 Disaster victims speak: Part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry 2002, 65, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zikmund, V. Health, well-being, and the quality of life: Some psychosomatic reflections. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2003, 24, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pollard, E.L.; Lee, P.D. Child well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 61, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflanz, S.E.; Ogle, A.D. Job stress, depression, work performance, and perceptions of supervisors in military personnel. Mil. Med. 2006, 171, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statham, J.; Chase, E. Childhood Wellbeing: A brief overview. In Children’s Society; Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre: Loughborough, UK, 2010; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, G.; Goswami, H.; Bradshaw, J. Developing an index of children’s subjective well-being in England. Child Indic. Res. 2010, 3, 523–543. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Brewin, C.R.; Kaniasty, K.; La Greca, A.M. Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2010, 11, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.; Boyko, C.; Codinhoto, R. Mental Capital and Wellbeing: Making the Most of Ourselves in the 21st Century; Foresight: Mental Capital and Wellbeing: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–172. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.C.; Johnson, D.M. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1978, 5, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.D.V.; Mangipudi, M.R.; Vaidya, R.W.; Muralidhar, B. Organizational climate, opportunities, challenges, and psychological wellbeing of remote working employees during the COVID-19 pandemic: A general linear model approach with reference to the information technology industry in Hyderabad. Int. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Technol. 2020, 11, 372–389. [Google Scholar]

- Dayal, G.; Divya, J.; Thakur, D.; Baddi, H.; Pradesh; Asamoah-Appiah, W.; Thakur, J. The challenges of human resource management and opportunities for organization during (COVID-19) pandemic situation. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2021, 7, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavic, A.; Poór, J.; Berber, N.; Aleksić, M. Human Resource Management in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic: Trends and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 26th International Scientific Conference Strategic Management and Decision Support Systems in Strategic Management, Subotica, Serbia, 21 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, J.B.; Hatak, I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer-Velush, N.; Sherman, K.; Anderson, E. Microsoft Analyzed Data on Its Newly Remote Workforce. Harvard Business Review, 15 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir, A.; Yossatorn, Y.; Kaur, P.; Chen, S. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivathanu, B.; Krishnasamy, G. COVID-19 pandemic: Impact on human resources and recommendations. Int. J. Manag. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2020, 5, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, W.; Gulati, G.; Kelly, B.D. Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, M. The roles of human resources in adapting organizational changes in COVID-19 pandemic. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2021, 28, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Sahoo, C.K.; Mishra, S. Impact of COVID-19 on employee engagement and motivation: Moderating role of organization type and sector. J. Public Aff. 2021, 22, e2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottaridi, C.; Antoniadis, C. Greek employers and employees: Attitudes toward the shift to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2021, 31, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, F.; Wei, L.; Bányai, T.; Nurunnabi, M.; Subhan, Q.A. An examination of sustainable HRM practices on job performance: An application of training as a moderator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paauwe, J. HRM and performance: Achievements, methodological issues and prospects. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancasila, I.; Haryono, S.; Sulistyo, B.A. Effects of work motivation and leadership toward work satisfaction and employee performance: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitz, A. The Triple Bottom Line; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hite, L.M.; McDonald, K.S. Careers after COVID-19: Challenges and changes. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, S.; Madgavkar, A.; Manyika, J.; Smit, S.; Ellingrud, K.; Meaney, M.; Robinson, O. The Future of Work after COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-Covid19 (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Devyania, R.D.; Jewanc, S.Y.; Bansal, U.; Denge, X. Strategic impact of artificial intelligence on the human resource management of the Chinese healthcare industry induced due to COVID-19. IETI Trans. Econ. Manag. 2020, 1, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, C. The challenges and opportunities of a global health crisis: The management and business implications of COVID-19 from an Asian perspective. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 19, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AM, E.N.; Affandi, A.; Udobong, A.; Sarwani, S. Implementation of human resource management in the adaptation period for new habits. Int. J. Educ. Adm. Manag. Leadersh. 2020, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc Su, D.; Luc Tra, D.; ThiHuynh, H.M.; Nguyen, H.H.T.; O’Mahony, B. Enhancing resilience in the COVID-19 crisis: Lessons from human resource management practices in Vietnam. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3189–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatiani, A.; Hämäläinen, J.; Penttinen, E.; Rossi, M. Constructing continuity across the organisational culture boundary in a highly virtual work environment. Inf. Syst. J. 2021, 31, 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeet, V.; Sayeeduzzafar, D. A study of HRM practices and its impact on employees’ job satisfaction in private sector banks: A case study of HDFC bank. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. Manag. Stud. 2014, 2, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R.; Bonett, D.G. The moderating role of employee positive well-being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpakumari, M.D. The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Job Performance: An Empirical Analysis. City Forum 2008, 9, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bańka, A.; Bazińska, R.; Wołoska, A. Polska wersja Meyera i Allen Skali Przywiązania do Organizacji. Czas Psychol. 2002, 8, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Becker, T.E.; Vandenberghe, C. Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Mahmood, B. Relationship between HRM Practices and Organizational Commitment of Employees: An Empirical Study of Textile Sector in Pakistan. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 6, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, D. Human Capital Management and Employee Engagement; Wydawnictwo C.H Beck: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; ISBN 978-83-8158-318-3. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M.; Taylor, S. HR Management; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: https://www.profinfo.pl/sklep/zarzadzanie-zasobami-ludzkimi,25308.html#informacje (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Hewett, R.; Shantz, A.; Mundy, J.; Alfes, K. Attribution theories in Human Resource Management research: A review and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 29, 87–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinabadi, H.; Salehi, K. Role of procedural justice, trust, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) of teachers: Proposing a modified social exchange model. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 29, 1472–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C. Evaluating the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Employee Organizational Commitment in the Taiwanese Banking Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Lynn University, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Masihabadi, A.; Rajaei, A.; Shams Koloukhi, A.; Parsian, H. Effects of stress on auditors’ organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and job performance. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2015, 4, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, R.C.; Kumar, N.; Pak, O.G. The Effect of Organizational Learning On Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and Work Performance. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2009, 25, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeese-Smith, D.K. The influence of manager behavior on nurses’ job satisfaction, productivity, and commitment. J. Nurs. Adm. 1997, 27, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, A.; Iles, P. Is continuance commitment beneficial to organizations? Commitment-performance relationship: A new look. J. Manag. Psychol. 2000, 15, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; Laverie, D.A.; McLane, C. Using job satisfaction and pride as internal-marketing tools. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q 2002, 43, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.; LePine, J.A.; Wesson, M.J. Organizational Behavior: Essentials for Improving Performance and Commitment; McGraw-Hill/Irwi: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, K.; LASCHINGER, H.K.S.; Shamian, J. Work Empowerment and Organizational Commitment. Nurs. Manag. 1996, 27, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, K. Encountering COVID-19: Human resource management (HRM) practices in a pandemic crisis. CJMR J. 2020, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.M.; El-Shafei, D.A. Occupational stress, job satisfaction, and intent to leave: Nurses working on the front lines during the COVID-19 pandemic in Zagazig City, Egypt. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8791–8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satankar, B. COVID-19 and its impact on human resource management practices. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2020, 8, 3713–3718. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouche, S. Human resource management and the COVID-19 crisis: Implications, challenges, opportunities, and future organizational directions. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 29, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseghale, R.; Ochie, C.; Dang, M.; Nyuur, R.; Debrah, Y. Human resource management reconfiguration post-COVID-19 crisis. In Organizational Management in Post Pandemic Crisis, Management and Industrial Engineering; Machado, C., Davim, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hemalatha, D.; Jambulingam, S. Role of corona pandemic on human resource management in private hospitals—A comparative study pre and post COVID-19 with special reference to Madurai district (TN). J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2022, 9, g402–g411. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, B.; Walarine, M.T. Human Resource Management: Pre-pandemic, Pandemic and beyond. Recoletos Multidiscip. Res. J. 2022, 2021, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.; Rahman, M.; Rahaman, S. Challenges for HR Professionals in the Post-COVID-19 Era. J. Bus. Strategy Financ. Manag. 2022, 4, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awu, E. The Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Human Resource Management and the Role Changes of HR Manager in an Organization. Acad. Res. Int. 2021, 5, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, S. Changing Role of HR Managers in COVID-19 Scenario. In Proceedings of the International E-Conference on Adapting to the New Business Normal—The Way Ahead, Mysuru, India, 3–4 December 2020; ISBN 978-93-83302-47-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rožman, M.; Peša, A.; Rajko, M.; Štrukelj, T. Building Organisational Sustainability during the COVID-19 Pandemic with an Inspiring Work Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Year | Recruitment Strategy Used | IT Tools Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| ILO [8] | 2020 | Shifting to online methods, prioritizing national recruitment, preparing for safe and fair recruitment practices | Job portals |

| Green [9] | 2020 | Adapting recruitment methods based on job requirements, utilizing social networks, online interviews, and psychometric tests | Job portals |

| Raveendra and Satish [10] | 2022 | Boomerang hiring (rehiring former employees) for restructuring organizations | Internal intranet |

| Mallik and Patel [11] | 2020 | E-recruitment systems and social media in sourcing candidates | LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter |

| Amaliyah et al. [12] | 2022 | Hybrid recruitment and selection system combining online and offline components | Hybrid system |

| Husna et al. [13] | 2021 | E-recruitment method through social media | Instagram, Facebook and Twitter |

| Siddharthan and Palani [14] | 2022 | E-recruitment, including social media hiring | Job portal like monster.com, nakuri.com, shine.com |

| Karasik [15] | 2022 | Door-to-door recruitment during the pandemic | No IT tools were used |

| Sands [16] | 2021 | Utilizing Facebook as a recruitment method | |

| TalentLyft [17] | 2022 | E-recruitment, sharing electronic information, and conducting online interviews | Job portal |

| Jezzini [18] | 2022 | Fostering a sense of belonging and providing additional value to candidates during the recruitment process | Facebook, LinkedIn |

| Author | Year | Performance Appraisal Strategy Used | IT Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bieńkowska et al. [19] | 2022 | Combination of “hard” and “soft” HRM strategies to shape job performance | Virtual meeting tools |

| Tovmasyan and Minasyan [20] | 2020 | Additional measures for employee well-being and satisfaction to enhance work motivation and job performance | Video Conferencing and zoom |

| Wolor et al. [21] | 2020 | Providing comfortable workspaces, remote work options, promoting well-being, fostering positive relationships, utilizing new technologies, and implementing appropriate communication processes to enhance work motivation and job performance | Virtual meeting tools |

| Vo-Thanh et al. [22] | 2020 | Positive relationship between satisfaction with organization’s COVID-19 responses and job performance | Electronic monitoring system |

| Chaker et al. [23] | 2021 | Indirect impact of social isolation on job performance mediated by job-related knowledge, informal communications, and loyalty to the organization | Virtual meeting tools |

| Sapta et al. [24] | 2021 | HRM practices fulfilling employee needs to stimulate job satisfaction and enhance job performance | Video conferencing |

| Granziera and Perera [25] | 2019 | Factors influenced by HRM, such as relationship with superiors, pay, opportunities for advancement and development, and relationships with co-workers, impacting job satisfaction and ultimately job performance | Virtual meeting tool |

| Sanders et al. [26] | 2020 | Effective communication, corporate social responsibility activities, supporting employees, and prioritizing well-being to enhance organizational commitment | Virtual team meeting |

| Author | Year | Strategy Used | IT Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mikolajczyk [33] | 2020 | Changes in employee development approach due to the pandemic | Video Conferencing Platforms |

| Saxena [34] | 2023 | Designing effective training programs during the pandemic | Virtual Reality (VR) Training Platforms |

| Al-Rawahi [35] | 2022 | Impact of training and development on employee performance during the pandemic | Online Surveys and Feedback Tools |

| HR Asia [39] | 2020 | Gamification in employee training and development | Learning Analytics Dashboards |

| Kumar et al. [40] | 2021 | Gamification as a sustainable tool for HR managers during the pandemic | Social Collaboration Tools |

| Shahriar et al. [41] | 2022 | Adoption of e-learning culture and flexible working arrangements during the crisis | Time Tracking and Productivity Software |

| Author | Year | Strategy Used | IT Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kelliher and Anderson [42] | 2019 | Flexible work arrangements | Video Conferencing Tools |

| Alon et al. [43] | 2020 | Salary freezes or reductions | Payroll Management Systems |

| Kang and Ding [45] | 2020 | Employer Aid Programs (EAPs) | Communication Tools |

| Gomez and Rosen [46] | 2020 | Expanded healthcare benefits and mental health support | Employee Wellness Apps |

| Liu and Zha [47] | 2021 | Open and regular communication about compensation and benefit changes | Intranet Software |

| Author(s) | Year | Strategy Used | IT Tools Used for Communication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. [68] | 2021 | Virtual team-building exercises | Zoom, Microsoft Teams |

| Ramalho et al. [69] | 2020 | Open and frequent communication | Slack, Microsoft Teams |

| Shaw et al. [70] | 2021 | Employee inclusion in decision-making processes | Not Specified |

| Wu et al. [71] | 2020 | Personalized communication and individualized support | Zoom, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams |

| Bravo et al. [72] | 2020 | Online communication platforms | Slack |

| Author Name | Year | Strategy Used | IT Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sibley et al. [73] | 2020 | Maintaining physical and mental health | Wellness Apps, Fitness Trackers |

| Wang et al. [74] | 2020 | Stress management | Meditation Apps, Mindfulness Apps |

| Qiu et al. [75] | 2020 | Face-to-face-like interactions for employee well-being during the pandemic | Counseling through Video Conferencing Platforms (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams) |

| Prasad et al. [88] | 2020 | Maintaining physical and mental health | Wellness Apps, Fitness Trackers |

| Author | Year | Challenges Faced |

|---|---|---|

| Dayal et al. [89] | 2021 | Finding high-quality candidates, reducing employee turnover and making hiring more efficient |

| Slavic et al. [90] | 2021 | Difficulties transitioning to remote work, ensuring employee safety |

| Carnevale and Hatak [91] | 2020 | Ambiguous working hours, increased workload, adapting to work-from-home environment |

| Singer-Velush, Sherman, and Anderson [92] | 2020 | Disconnection from social life, lack of continuous business activities, employee safety concerns, changing customer preferences |

| Dhir, Yossatorn, Kaur, and Chen [93] | 2020 | Managing remote work arrangements, virtual collaboration, and communication among remote teams |

| Sivathanu and Krishnasamy [94] | 2020 | Managing workforce planning and resourcing, including workforce reductions, layoffs, and talent acquisition in a remote work environment |

| Cullen, Gulati, and Kelly [95] | 2020 | Promoting employee well-being, addressing mental health concerns, and providing necessary support and resources |

| Nguyen and Nguyen [96] | 2021 | Managing organizational change, facilitating remote onboarding, and helping employees adapt to new work arrangements and technologies |

| Mishra, Sahoo, and Mishra [97] | 2021 | Maintaining employee engagement, motivation, and job satisfaction amidst uncertainties and remote work arrangements |

| Kottaridi and Antoniadis [98] | 2021 | Managing legal and compliance issues related to remote work, health and safety regulations, and labor laws during the pandemic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Selvaraj, V.; Venkatakrishnan, S. Role of Information Systems in Effective Management of Human Resources during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Systems 2023, 11, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11120573

Selvaraj V, Venkatakrishnan S. Role of Information Systems in Effective Management of Human Resources during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Systems. 2023; 11(12):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11120573

Chicago/Turabian StyleSelvaraj, Vishnupriya, and Santhi Venkatakrishnan. 2023. "Role of Information Systems in Effective Management of Human Resources during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Systems 11, no. 12: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11120573

APA StyleSelvaraj, V., & Venkatakrishnan, S. (2023). Role of Information Systems in Effective Management of Human Resources during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Systems, 11(12), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11120573