Abstract

Solutions will be effective if they are aligned with the problems that they are trying to solve. This paper studied the most relevant social impacts of the textile industry and how appropriately textile companies manage these social impacts, in order to achieve greater social sustainability in global supply chains. Therefore, we attempted to determine whether companies belonging to the textile product lifecycle identify and manage social impacts in keeping with the most relevant social hotspots in the supply chain of the textile industry. A consistency analysis was conducted based on the management of social indicators at the company level (identified through the analysis of contents of their sustainability reporting) connected with social impact categories defined in the Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of products provided by the United Nations Environment Programme, and the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, and on the technical results obtained by the textile sector through the Social Hotspots Database. The results showed a predominant inconsistency between the main social hotspots of the textile industry showed in the footprint analysis and the social indicators specifically reported by the sector. This paper contributes to the literature about what sustainability management implies along global supply chains, emphasizing the need to advance in a consistent and science-based integration of social hotspots at the sectoral level and social management practices at the company level. In addition, the study could be relevant for companies belonging to complex and global supply chains, since it contributes towards enhancing the knowledge of science-based methodologies, as social life cycle assessments, for identifying, managing, and reporting their social hotspots.

1. Introduction

The study of sustainability in global supply chains has gained momentum in the last two decades [1]. Nevertheless, the social dimension of sustainability is an under-explored area [2,3,4,5,6] compared with environmental studies. This supports the necessity to assess sustainability along supply chains, as well as holistically, as Bubicz et al. [7] states, taking into account the different activities and enriching the scarce knowledge about their social dimensions.

This study focused on the supply chain of the textile industry since, according to Khan et al. [6], solutions to social sustainability in supply chains, especially in multi-tier supply chains, are very sensitive to the sector. Sodhi and Tang [8] highlighted the great relevance of the textile industry in this context, considering it as ‘a major source for environmental and social sustainability concerns’. Shocking contemporary cases (such as the Rana Plaza collapse or, more recently, the Tangier and Cairo tragedies) show how significant social issues along supply chains are, with regard to attaining the sustainability goals which are highly relevant to the textile industry.

The apparel industry is one of the most studied in the literature concerning social sustainability in supply chains [7,9]. Nevertheless, as Sodhi and Tang [8] point out, the number of publications in this regard is still relatively small, which proves that research on social sustainability in the apparel industry also remains underdeveloped [10]. It is necessary for the scientific community to contribute with specific research towards the development of a solid and science-based social foundation, where companies can identify and manage their main social impacts, and where other market actors (consumers, regulators, etc.), can position themselves in their decision-making process in favor of a more social sustainable development. Nevertheless, there are several challenges to overcome, both theoretical and practical.

Market actors need a consensus definition regarding what social sustainability means. It is a challenge since, as Jia et al. [3] state, its ambiguity leads to different interpretations. In this regard, for the purpose of this research, this paper follows the review of social sustainability definitions in the supply chain management field carried out by Nakamba et al. [2], where social sustainability relates with ‘the management of practices, capabilities, stakeholders, and resources to address human potential and welfare both within and outside the communities of the supply chain’. It is also connected with Mani and Gunasekaran [11] perspective, which relates social sustainability in the supply chain with the Wood’s [12] definition of social performance, considering that are those aspects associated to product and process that ‘affect the people’s safety and welfare’. In addition to principles and processes, it includes outcomes, understood as social policies, programs, and impacts [12].

Based on Meehan et al. [13] and Huq et al. [10], Akbar and Ahsan [14] define social sustainability policies as those which concern the use of social resources by organizations and reflect the organizational social and ethical commitments, their relationship with partners in the supply chain and their behavioral consistency over time. Social policies that are not isolated, but based on commitments, are required, which create social networks along the supply chain and are intertemporally consistent.

Social programs can act as ‘vectors’ of social sustainability in supply chains that reach beyond social policies. Regarding social impacts, both the scope of impacts (internal and external) and their results (address human potential and welfare) must be addressed. This approach to social impacts specifies a ‘what for’ nuance in the general definition of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) provided by Seuring and Müller [15], who defined SSCM as ‘the management of material, information and capital flows as well as cooperation among companies along the supply chain while taking goals from all three dimensions of sustainable development, i.e., economic, environmental and social, into account which are derived from customer and stakeholder requirements’ which offers the answer ‘to address human potential and welfare both within and outside the communities of the supply chain’. Therefore, the actors involved can broaden the conceptual framework proposed by Köksal et al. [16] for the textile and apparel industry which focuses on customers, government, NGOs, focal companies, and suppliers.

In a complex and dynamic environment with resource allocation constraints, it is relevant to identify the most significant social issues following a science-based method for their assessment using specific indicators and their translation into useful information for the decision-making process of the different actors. In this sense, social life cycle assessment is a social impact assessment methodology, with a product life cycle perspective that is useful for the identification of social hotspots along global supply chains [17].

The concept of social sustainability and its application to an entire supply chain, its operative translation into performance indicators, and a science-based identification of the most relevant social issues, require consistent alignment. These elements act as pieces of a puzzle where all are necessary for the complete picture, in this case, for managing and accountability of the right social issues in order to advance a more socially sustainable supply chain. The requirement of consistency between what organizations declare and manage and the issues that are relevant considering their impact on the social system where the organization operates rely on the theory of legitimacy [18]. In this regard, for this paper, social hotspots are viewed as those whose management is socially desirable due to their relevance for a greater social sustainability of a supply chain. As Mani and Gunasekaran [11] state, social sustainability is frequently used as an organizational strategy to ensure acceptance from society. Inconsistencies could originate not only inefficiencies in the allocations of resources for sustainability issues management but also the risks of ‘socialwashing’ perceptions.

In this context, the objective of this paper was to explore the consistency between the nature of the most relevant social impacts that textile companies should manage and the current situation regarding this management by companies, for achieving greater social sustainability in the supply chains they belong to.

Hence, the specific research questions of this paper are:

RQ1:

What social dimensions should textile companies include in their sustainability management, since their social impacts go beyond their boundaries, extending downstream and upstream along the supply chain?

They should be at least those that are critical for the company, considering the nature of its activity (sector) and the social hotspots of its product under a life cycle approach. Consequently, it is crucial to empirically identify what these social hotspots are and to explore whether textile companies are managing them consistently with a more socially sustainable supply chain.

RQ2:

Are companies along textile supply chains identifying and managing their social impacts regarding relevant social issues, in accordance with textile industry social hotspots?

Following Zamani et al. [19], textile industry social hotspots are defined as ‘activities throughout the life cycle that are associated with higher risks of social violations associated with labour rights, health and safety, governance, community infrastructure and human rights’. Previous studies on sustainability impact measurement of the textile industry along the supply chain using real-life cases show a disconnection between current environmental practices carried out by companies and their real hotspots considering sectoral environmental data technically assessed [20]. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no similar study regarding social impact management has been carried out yet.

Several social agents may benefit from accessing this information. On the one hand, this paper contributes to the existing literature about social sustainability supply chains’ management, offering academics empirical insights on the social hotspots of the textile industry supply chain and by measuring the consistency with which companies in the textile industry manage those social hotspots. In addition, textile sector managers can integrate the results of the analysis to increase consistency and efficiency in company information and organizational structures, including those related to their supply chain partners. On the other hand, external stakeholders of sustainability reporting (rating agencies, consumers, society in general, etc.) can have access to technical and science-based information on the relevance of the information reported and on the key issues to satisfy their accountability demands. In addition, public authorities can make use of this information as an input to formulate future policies, regulations, or support programs.

The remaining part of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 begins by presenting a literature review on social sustainability in supply chains and associated social impacts. This section also brings into focus the role of the social life cycle assessment as an accurate tool for measuring and managing textile social impacts. Section 3 offers an explanation of the research design, and the main results of the consistency analysis are shown in Section 4. Section 5 includes a discussion of the implications of the findings, and the final section highlights the main conclusions of this research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Sustainability Analysis in Supply Chains

Based on the above-mentioned definition of SSCM, social sustainability can be linked to the assessment of processes (within an entire supply chain) and products (under a life cycle perspective) to identify the social and economic circumstances of the different market actors who belong to the supply chain [21,22], both directly (within the communities of the supply chain) or indirectly (outside these communities). A key issue is to clearly identify, upstream and downstream, which social issues to address, e.g., Quarshie et al. [23], in their analysis of social sustainability research in supply chains, identified that research regarding social concerns of raw material producers such as impacts on communities and social equality, is one of the main research gaps.

According to Matos et al. [24], the problem of selecting the appropriate methodological approach to identify and analyze relevant information and avoid weaknesses in the assessment of sustainability aspects is not new in the literature about sustainable operations and supply chain management. However, as Kelling et al. [25] mention, there is a lack of empirical research regarding the social dimension un supply chain research, specially about upstream issues and labour-intensive industries, probably influenced by the absence of conceptual frameworks and established theories in social sustainability pertaining to multi-tier supply chains mentioned by Govindan et al. [26]. Therefore, more than one theory is commonly employed by researchers in the development of their models, such as the stakeholders’ theory or the institutional theory, among others [21,26]. In addition, studies such as Matos and Hall [27], used the theory of complexity for analyzing the integration of sustainable development in the supply chain. More recently, Najjar and Yasin [28] based their research regarding the management of global multi-tier sustainable supply chains on a complexity theory perspective. Specifically, they adopted the social systems theory, highlighting the complexity associated with the inter (internal complexity) and intra (collective complexity) relationships among the actors belonging to the system. Despite the fact that complexity theories are relatively recent, they merge sciences such as political, management and organization, public administration, biology and physics sciences [29]. It is a very interesting theory for the study of social sustainability dimensions of supply chains, especially for the basic idea described by Byrne [30], who noted the relevance of identifying the key control parameters within the large numbers of parameters that could determine the state of a complex system, considering that in social issues these relationships used to be non-linear. This idea of control parameters can be associated to the concept of hotspot in a supply chain, allowing to identify the most relevant social dimensions and activities of the whole system.

Based on Muñoz et al.’s [31] corporate sustainability assessment framework, the identification of the typology of social dimensions that should be analyzed within a supply chain is not an isolated task. It is integrated in, and should be aligned with, a corporate sustainability assessment framework, which includes policies and commitments with social concerns, the quantification of the social footprint, the identification of social hotspots, and the assessment of such information for better decision-making process. This view aligns more socially sustainable organizations, within a more socially sustainable supply chain, and, at the end, within a more socially sustainable society.

These premises show how challenging it is to devise specific measures in order to materialize social sustainability and to measure a social footprint, especially due to the usual complexity which arises from the dynamic and complex nature of social issues in supply chains [32], from the definition of accurate issues for making the social sustainability concept commensurable following the previous definitions and scope, and from the need of integrating a multi-stakeholder approach in the range of social issues included in the assessment [33]. Furthermore, it is necessary to advance towards making them operational and quantifiable in order to be able to measure the social footprint of the organization along the entire supply chain. To that end, it is crucial that the existence of specific social impact indicators be related to these social issues.

In this regard, Beske-Janssen et al. [34] highlighted that less attention is devoted to social measures in the studies about assessment of supply chains. The scientific community has put in a great deal of effort to avoid the use of social indicators since it considers that they are ‘subjectively perceived and hard to evaluate’ [7]. Ahmadi et al. [35] stated that current tools for assessing social issues in a supply chain based on social indicators are ‘limited and are often prone to subjectivity’.

Nevertheless, avoiding subjectivity does not imply eluding the necessary integration of those concerns pertaining to the stakeholders that are being affected by the organizations’ activity. Following the theory of stakeholders, social sustainability in the supply chains entails raising awareness of impacts, downstream and upstream, inside and outside the chain among the different stakeholders that act as a network along the supply and act accordingly to manage them. Consequently, the most relevant social hotspots beyond the boundaries of the organization should be identified, assessed, and managed. In the same vein, Govindan et al. [26] suggest the development of quantitative models for ‘holistic and objective assessment of social sustainability performance of a multi-tier supply chain network’. This quantification may be regarded as the social footprint of the organization analyzed and, as Čuček et al. [36] mention, the social footprint is a ‘measurement for quantifying the social sustainability performance of an organization’. The specific social dimensions that could cover this social footprint can be defined considering several standards developed to guide the organizations towards social sustainability. The most representative and widely accepted standards are: (i) SA8000, an international certification standard focused on the organizational management of social issues at the workspace; (ii) GRI Standards, focused on the sustainable reporting under the triple bottom line; (iii) ISO 26000, which guides organizations in the integration of management systems related to corporate social responsibility; and (iv) Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of products provided by the United Nations Environment Programme and the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, UNEP-SETAC [37], which integrates a life cycle approach in their proposal for identifying social impacts. These standards address social sustainability concerns from different approaches. Despite the life cycle approach of UNEP-SETAC Guidelines makes them the most relevant for the purposes of this research, the social dimensions they tackle can be related each other

Specifically, regarding social issues in the textile industry, social concerns in previous studies have been mainly focused on human rights and worker safety and welfare [14] or decent work [38] expressed as adequate income, work relations, work duration and intensity, company development, social insurance, work-life balance, job security, fair and equitable treatment at work, skills training, and trade unions. A literature review developed by Köksal et al. [16] also highlights social criteria such as child and forced labor, unhealthy or dangerous working environment, and discrimination. In addition, as Huq et al. [10] mention that community welfare and development should be included in the social criteria. Nevertheless, there is a need to advance into the social sustainability management of the supply chain of textile products from a more holistic approach.

2.2. Social Life Cycle Assessment for Quantifying Social Impacts and Identifying Social Hotspots along Global Supply Chains of the Textile Industry

Several features of the textile industry make the management of social issues especially challenging.

The textile industry supply chain is global and characterized by the size and diversity of its numerous members operating in every region around the world; all small, medium, and large manufacturers are under pressure to keep costs down, innovate products and meet tight deadlines [39]. High social impacts are perceived in the textile industry concerning the complexity and heterogeneity of a chain of suppliers frequently operating in developing and low labor-cost countries [10,14,38,40].

Another relevant issue regarding the management of companies belonging to textile products supply chains, is that the textile industry is characterized by the prevalence of an asymmetric relationship between powerful retail buyers and small suppliers [41]. In a context where different stakeholders exert pressure on companies to account for social sustainability issues [11,42], requirements regarding social impact management for companies, especially for larger ones, have adopted a multi-tier approach where organizational social practices are analyzed considering their products and the supply chain they belong to [43,44]. The institutional theory maintains that the scrutiny of different stakeholders makes organizations determine these practices to address social demands and gain legitimacy; however, more empirical research concerning social dimension is needed [25]. It is also necessary to extend this research about social sustainability to the entire supply chain, including the perspective of other non-traditional members, such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and communities [25].

The use of a technical approach will enable organizations to quantify and identify their most relevant social impacts on a variety of stakeholders along the entire supply chain, within the organizations’ boundaries and beyond them. This section will focus on this question. Following the work of Villena et al. [45], this research adopts the supply network as unit of analysis but considering the different phases that the supply chain of a textile product can have, and the impacts that these products and their associated processes can produce along its life cycle.

Life cycle assessment (LCA) approaches are among the most used methodologies for measuring sustainability performance in the management of supply chains [20,31,34,46] since the full product life cycle can be the perspective adopted for the evaluation of impacts along the whole supply chain. In social terms, despite Nakamba et al. [2] highlighting the absence of a unified approach for measuring the actual corporate social performance in supply chains, according to D’Eusanio et al. [22], a predominance of publications also proposes a life cycle thinking perspective. For that purpose, Bubicz et al. [7] recommend social life cycle assessments (SLCA).

According to the review conducted by Huarachi et al. [47] on the historical evolution and research trends of social life cycle assessments, ‘SLCA is in its best era and caught the attention of sustainability practitioners, however, there is still a long way ahead to achieve a real standardization’. In this sense, the authors highlight the significant role developed by the Guidelines for SLCA of products (see UNEP-SETAC, [48] for a detailed description of this method), the Methodological Sheets for Subcategories [49], and the Social Hotspots Database (SHDB) [50] to standardize SLCA.

The Social Hotspots Database has been applied at the sectoral level, including the textile sector, for identifying social hotspots [51].

Roos et al. [52] use a life cycle assessment-based approach focused on apparel sector sustainability, including social sustainability, in Sweden. The SHDB data helped to identify social hotspots for the Swedish case; it concludes that the significant social risks in the textile and clothing industry are related to wage, child labor, and exposure to carcinogens at workplaces. These results were used for analyzing the effectiveness of Swedish apparel industry interventions in order to reduce these social risks.

The research carried out by Lenzo et al. [53] includes a SLCA of a textile product made in Sicily (Italy), following the Guidelines for SLCA of products [48] and using the SHDB for the upstream supply chain data. Results highlight the complexity of the textile supply chain, whose social problems arise mainly at the national or global level.

Zamani et al. [19] have followed the SLCA method to identify social hotspots in the clothing industry, which focused on the case of Swedish clothing consumption. SHDB was used at a sector and country level for developing an impact assessment; yet it included a limited set of social indicators that represented those indicators prioritized by consumers. Child labor, injuries and fatalities, and toxics and hazards were identified among the most relevant social issues.

The work of Zimdars et al. [17] proposes an SLCA method which includes environmental and economic aspects based on the Guidelines and the SHDB and EXIOBASE, and tests it in two case studies, in which a T-shirt is one of the products analyzed. This study includes life cycle thinking but excludes the use and disposal life cycle phases. Among the conclusions obtained, the authors recommend caution in the use of databases based on multi-regional input-output tables for quantitative product comparison, even though they highlight their relevance for identifying hotspots.

To our knowledge, no previous research on the textile industry social hotspots analysis has been carried out with a global perspective, which may consider the whole life cycle of the products in international supply chains, and which compares them with the management practices carried out by the most relevant sustainability performers of the textile sector supply chain. It shows the need to delve into the social sustainability management of textile products supply chain, based on a more technical approach. To address the objective of this paper, in a first stage, we will carry out a technical analysis of the entire textile products supply chain in order to identify their social hotspots, joining a theoretical approach based on the literature review with a quantitative analysis of a SLCA applied over a simulated (generic) textile supply chain (RQ1); in a second stage, we will analyze the information provided by the most relevant textile companies in their sustainability reports, using UNEP-SETAC Guidelines, with the aim of identifying social impacts currently managed by companies placed along the textile products supply chain. Finally, we will compare both approaches, so potential inconsistencies between them could arise (RQ2).

3. Materials and Methods

In order to assess the suitability of the SHDB for the study of textile industry social hotspots in a social sustainability of supply chain context, besides the conclusions obtained from the literature review, several key issues should be explored.

On the one hand, social categories, and impact categories (themes) of the SHDB [54] are pertinent for the textile sector study according to the present literature review (they relate to human rights, worker safety and welfare, decent work, child and forced labor, unhealthy or dangerous working environment and discrimination and community welfare and development).

Furthermore, SHDB can be useful for making social impacts operational, following the SHDB multi-actor perspective methodology and the different process structure, that is: Data origin and data collection [50], following criteria of comprehensiveness and legitimacy of the data, and come from international organizations such as the World Bank, ILO or WHO, among others; and characterization of the level of risk associated with every social impact category [54] and the Social Hotspot Index calculation [54].

Finally, all social theme tables, indicators, and characterized issues are described in detail by Benoit-Norris et al. [54]. Social categories and impact categories in the SHDB provide relevant information so as to make the social sustainability concept commensurable in a supply chain context. The current analysis includes the disaggregated indicators provided by Benoit-Norris et al. [54] which are associated with the measurement of these categories; these indicators can be related to:

- the means to achieve social sustainability: practices (v.g. percentage of Child Labor by sector), capabilities (v.g. Gender equity), stakeholders (v.g. Indigenous Rights Infringements) and resources management (v.g. Sector Average wage);

- the scope of social impacts both internal (v.g. Occupational Noise Exposure) and external (v.g. Access to Improved Sanitation);

- social sustainability results that address human potential and welfare (v.g. Access to Hospital Beds).

Moreover, the SHDB allows the identification and study of all potentially relevant social issues, since it is directly connected with SLCA UNEP-SETAC Guidelines, which, at the same time, are related to other social management tools as SA8000, GRI Standards and ISO 26000. Regarding the role of stakeholders in the process, as Subramanian et al. [55] state, there is no current normative approach for the integration of stakeholders in the impact assessment methods in SLCA. The technical approach presented in the SHDB does not include stakeholders’ choice; however, stakeholders’ needs and expectations are integrated in the method, since different actors such as workers, indigenous people, migrants, or local communities have a direct connection with specific social issues.

Consequently, for the purposes of this research, both UNEP-SETAC [37] Guidelines for SLCA and SHDB [54,56] have been used.

Research Design

To answer the research questions, the following issues have been addressed:

- (i)

- Definition of textile product life cycle stages;

- (ii)

- Assessment of the textile industry social hotspots (SHDB); and

- (iii)

- Study of the social impacts identified and managed by textile companies (using [37]).

For the assessment of the textile industry social hotspots, a technical SLCA assessment has been applied, which adapts the life cycle of the product to a specific textile product: cotton-made t-shirt [20]. Beton et al. [57] demonstrate the relevance of a t-shirt made of cotton to the European clothing market.

The quantitative data regarding the social impacts for the textile sector has been simulated through an ideal life cycle for an iconic textile product, the T-shirt and calculated using SimaPro, with real data obtained from the Social Hotspots Database (SHDB) v2.1., considering 1 cotton-made t-shirt as the functional unit.

The SHDB allows to identify not only social hotspots, but the sectors and countries for product supply chain, considering possible social impacts. The database provides 22 Social Themes Tables regarding five social categories (Labor Rights, Health & Safety, Human Rights, Governance, and Community). Lifecycle social impacts are assessed and quantified using the SHDB_Ecoinvent_Hybrid_2017_v1_version84, taking into account social impacts associated to production and consumption as a characterization model.

For the selection and identification of hotspots in the simulated scenario, this research uses the global supply chain previously defined by Muñoz et al. [19]: (i) raw material procurement (cotton): 15.6% from USA, 29.8% from China, and 54.6% from the rest of the world, mostly Pakistan and India; (ii) fabric manufacture: China; (iii) garment production: Turkey; (iv) consumer use phase, including the possibility of reuse, located in: Germany, a developed country, with 40 cycles of washing and drying; and a reuse phase located in Ivory Coast, considered to be a low income country, where the t-shirt is hand-washed for 25 cycles; and (v) product end of life: incinerated as municipal solid waste.

The social footprint for the simulated scenario has been used to identify social hotspots.

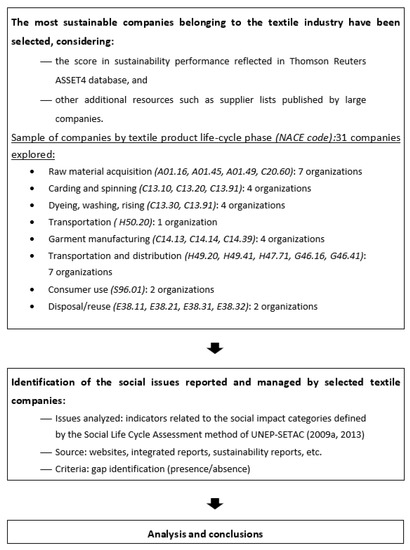

As for the study of the social impacts identified and managed by textile companies, Figure 1 explains the process in detail.

Figure 1.

Procedure for the identification of the social impacts managed by textile companies. General outline. Source: Muñoz et al. [58] and own elaboration.

Thomson Reuters ASSET4 database only includes listed companies. For the current study it is relevant since, as Sodhi and Tang [8] remark, large companies influence the social conditions of their supply chains by improving or deteriorating them. However, other resources have been used for companies to be considered for their remarkable sustainability management. A total number of 31 companies, heterogeneous regarding their geographical location, were explored according to the available information. Different economic activities (NACE codes), associated with the textile product life cycle, were represented in the analysis. The analytical process was carried out categorizing the information according to the social impact categories defined in the social life cycle assessment method of UNEP-SETAC [48,49]. Moreover, especially in case of qualitative data, the authors discussed the link between information and social subcategory, so avoiding the analyst bias. Details are available upon request. The results by life-cycle phase are reflected in Table 1.

Table 1.

Textile industry social hotspots and social aspects managed and reported by selected textile companies-comparative analysis.

The analysis of social aspects measured by the selected textile companies was carried out by the authors jointly with a group of multidisciplinary experts in April, May, and June 2018; it focused on the study of their sustainability reports and other public information available on their websites. Sustainability reports can provide analysts with information about current sustainability practices along the supply chain from the viewpoint of industries [59]. As main limitation of this method, it should be remarked that this information is not externally audited.

4. Results

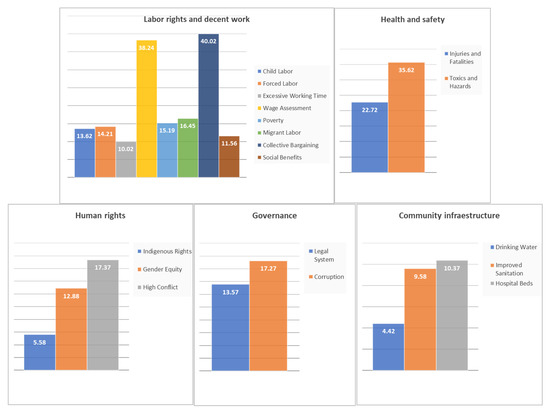

Results regarding the main social dimensions of the textile industry along a global supply chain, are included in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Social impact categories classified by social category. Weighted Results.

The scores in each subcategory reflect worker hours (relevant information for representing the intensity of work required by each country specific sector directly related to each supply chain phase), adjusted by risk levels. For example, regarding child labor, as SHDB states, it means “% of worker hours that present a high or very high risk of child labor”.

Results are integrated in Table 1:

- (i)

- Red words reflect the most relevant social impact category following SHDB outputs;

- (ii)

- The numbers (in percentages), are the cumulative impact “contribution” to the whole social impact of each life cycle phase, classified by impact category. Numbers in bold represent the cotton t-shirt lifecycle phase that reaches 50% of cumulative impact contribution to the considered social impact category;

- (iii)

- Color in cells represents the relevance of each social impact for the textile industry, considering their presence in the public sources analyzed (websites, integrated reports, sustainability reports, etc.): green when 100% of the companies in the sample define at least one indicator linked with the subcategories; red when none of the companies defines an indicator linked with the subcategories; and yellow, otherwise;

- (iv)

- The joined analysis of all previous data gives information regarding the level of consistency: consistent, when SHDB output and the social aspects reported and managed by selected companies of the textile industry coincide; non-consistent, when SHDB output and the social aspects managed and reported by selected companies differ; or partially consistent, when SHDB output and the social aspects managed and reported by selected companies coincide to some extent.

Considering the relevance of each life cycle phase in their “contribution” to the generation of each social impact category, Table 1 shows as ‘Fabric production’, and ‘Raw material acquisition’ are the critical phases for all the social impact subcategories considered. ‘Fabric production’ occupies the first position in all the social impact subcategories except in terms of ‘indigenous rights’ subcategory, where ‘Raw material acquisition’ is the most significant phase.

Consequently, regarding RQ1, what social dimensions should textile companies include in their sustainability management, since their social impacts go beyond their boundaries, extending downstream and upstream along the supply chain? The answer, by social category, provided by the SLCA carried out is:

- Labor rights and decent work: ‘Wage Assessment’ and ‘Collective Bargaining’, especially during the fabric production phase;

- Health and safety: ‘Injuries and Fatalities’ and ‘Toxics and hazards’, especially during the fabric production phase;

- Human rights: ‘High Conflict’, especially during the fabric production phase;

- Governance: ‘Corruption’, especially during the fabric production phase;

- Community infrastructure: ‘Hospital beds’, especially during the fabric production phase.

Results concerning consistency analysis based on the comparative results between the social topics identified and managed by companies in the textile sector and these sectoral social hotspots, are reflected in Table 1. It also includes a correspondence study of social impact categories used by the SHDB and social issues catalogued by UNEP-SEPAC [48,49]. In some cases, the relation is not direct, since UNEP-SETAC focuses on social life cycle assessment of products and SHDB has a more process-oriented and country-oriented approach. However, in cases of no direct relationship, the correspondence study has been carried out according to the similarities in the social objective pursuit by the issue included in each side. Despite the absence of a literal correspondence between some indicators, the analysis answers the specific research question that drives this work: Are companies, which belong to the different textile product life cycle stages, identifying and managing their social impacts regarding relevant social issues, in accordance with textile industry social hotspots? (RQ2).

Results in Table 1 show that the answer is ‘no’, since there is a prevalence of inconsistencies between the social hotspots identified for the textile industry and the most relevant social issues managed by textile companies according to the information retrieved. The greater consistency is presented in issues associated to health and safety of workers/employees.

Regarding the ‘Labor rights and decent work’ social category, the relevance of ‘Collective Bargaining’ and ‘Wage Assessment’ in ‘Fabric production’ life cycle stage (which includes ‘Carding and spinning, ‘Transportation’ and ‘Dyeing, washing and rising’) is established. In this sense, the textile industry partially covers the sub-stage ‘Carding and spinning’ regarding ‘Collective Bargaining’ (‘Wage assessment’ remains uncovered). Textile companies gave wider coverage of the ‘Migrant Labor’ social category, in all life cycle stages except ‘Dyeing, washing and rising’. Nevertheless, this social impact is partially relevant to the hotspots analysis for the industry based on the SHDB data. They have also given higher coverage for the ‘Social Benefits’ social category, but it is a scarcely relevant social impact category for the industry according to the SHDB hotspots analysis. Consequently, it presents a partial consistency.

Concerning the ‘Health and safety’ social category, SHDB data emphasizes the importance of the ‘Toxics and Hazards and ‘Injuries and fatalities’ social impact categories in the ‘Fabric production’ life cycle stage. There is a total or partial coverage of textile company management in all stages except ‘Dyeing, washing and rising’, but only associated to workers; other stakeholder indicators are uncovered along the whole life cycle (‘Consumers-Health and safety’) or scarcely covered in less relevant life cycle stages (‘Local Community- Safe and healthy living conditions’ in ‘Garment manufacturing’ and ‘Transportation and distribution’ stages). In sum, it also presents a partial consistency.

With regard to the ‘Human rights’ social category, the ‘High conflict’ social impact category in the ‘Fabric production’ life cycle stage is highly relevant. Nevertheless, this social impact is apparently uncovered by textile companies in this stage, since they do not report any indicator related to this issue (nor in the next stage, ‘Raw material acquisition’, which is also important although to a lesser extent). On the contrary, textile companies show total or partial coverage of ‘Gender Equity’ management in all life cycle stages except ‘Dyeing, washing and rising’. In social hotspots terms, it is inconsistent.

As far as ‘Governance’ is concerned, the most relevant social impact category is ‘Corruption’ in the ‘Fabric production’ stage. Not only have textile companies withheld information related to the ‘fabric production’ but also related to most of the whole life cycle. It denotes apparently deficient management of this social impact which is not improved when the scope of the study is expanded to include the ‘Legal System’ social impact category; only some aspects in this regard are partially dealt with (v.g. ‘Consumer-Feedback mechanism’ in the stages ‘Garment manufacturing’, ‘Transportation and distribution’ and ‘Disposal/reuse’; or ‘Value chain actors- Promoting social responsibility’, in stages ‘Carding and spinning’, ‘Garment manufacturing’ and ‘Transportation and distribution’).

The study of the ‘Community infrastructure’ social category sees the relevance of the ‘Hospital Beds’ social impact category in the ‘Fabric production’ life cycle stage. This social aspect has been associated with ‘Local Community- Safe and healthy living conditions’ and ‘Local Community- Access to material resources’ UNEP-SEPAC issues, which are not covered by textile companies in their reported sustainability management. In fact, only ‘Local Community- Safe and healthy living conditions’ is partially covered in the stages ‘Garment manufacturing’ and ‘Transportation and distribution’. Therefore, it is not consistent according to textile industry social hotspots.

Supplementary Materials Table S1: ‘Summary of consistency results’ summarizes these results.

Finally, by the life cycle stage, ‘Garment manufacturing’ and ‘Transportation and distribution’ companies have been the most advanced companies due to their social accountability; yet their contribution to the overall social impact is less significant in relative terms compared with ‘Fabric production’ and ‘Raw material acquisition’ stages. The companies of these above-mentioned life cycle stages are the most important ones according to their social cumulative impact, even though they have the greatest management deficit of their social impacts.

5. Discussion

Companies primarily focus on workers’ social issues, which is not necessarily a wrong management strategy since these aspects are also traditionally relevant to the textile sector [14,38]. In fact, ‘Health and safety’ is one of the social hotspots for the textile industry according to the study based on the SHDB. Nevertheless, controversy arises when other relevant issues for workers, such as collective bargaining or wage assessment, received less attention by companies in the most critical phases, i.e., ‘Fabric production’. In a sector characterized by operating in low-income countries with a high risk of unbalance in labor standards, mismanagement of collective bargaining limits workers’ capability to claim their rights and reduces their ability for empowerment, which, in the end, can have consequences beyond their position as employees. In addition, concerning human rights, the social hotspot poses a major risk in the ‘Fabric production’ and ‘Raw material acquisition’ phases, which are almost absent in the management of the companies analyzed. This could be explained by the fact that a high percentage of cotton is produced in developing countries, where the cotton supply chain is characterized by asymmetries among the different actors, from small and marginal farmers to ‘sophisticated’ mills and textile processors [60].

‘Governance’ in general and ‘corruption’ in particular are a challenge for textile companies, deeply significant in the ‘Fabric production’ stage. Luque and Herrero-García [61] highlight the relevant role of transnational companies of the textile sector in processes of corruption, by an act or omission. Furthermore, Bubicz et al. [62] noted that anti-corruption practices are observed in focal companies but not in sub-suppliers. This inconsistency, together with that showed by the social category ‘Community infrastructure’ (social hotspot in ‘Fabric production’ stage), shows the limited attention paid to social impacts on communities outside the supply chain. A supply chain cannot be socially sustainable without considering the welfare of communities along these supply chains, so textile companies should make progress in managing those aspects that affect the society negatively, both in the short and in the long term.

In addition, according to Govindan et al. [26], multi-tier supply chains can suffer from sustainability tensions, so it is necessary to develop a social sustainability model and framework with a multi-stakeholder approach. As a consequence, this model will increase the sustainability leadership of leading companies in global supply chains and reflect the need to encourage the use of sustainability assessment tools that reinforce stakeholders’ engagement and integrate supply chain sustainability performance into these assessment processes [31].

In this regard, as stated by Jørgensen et al. [63], the SLCA can promote changes in product life cycles when it is integrated as a tool for supporting the decision-making process of companies through, among others, the ‘lead firm’ SLCA. It focuses on the possibility of company managers to change the behavior of their company, as well as in other companies of the product chain, because of the information given by the SLCA for identifying the social hotspots to be managed. The latest argument is especially appropriate in a textile sector context since, as Bubicz et al. [62] remark, the apparel industry supply chain network is regarded as a centralized supply chain, where the lead company manages its brands using strategic control along with the network.

This paper demonstrates the need for devising novelty and holistic sustainability assessment methods as a solution [31] that define the green economy in an integral way to avoid the existence of, for example, an environmentally sustainable industry with child labor.

Nevertheless, the development of this research presents some limitations. The analysis of social management practices and initiatives along the entire supply chain has been carried out based on the public information reported by a selection of companies for each lifecycle phase of a textile product. The lack of standardized social indicators entails the risk of displaying bias in the interpretation study carried out by the analysts, also applicable in the correspondences defined between social impact categories used by the SHDB and social issues cataloged by UNEP-SEPAC [48,49]. However, the intervention of more than one analyst in each analysis has reduced the potential bias. In addition, Subramanian et al. [55] mention that existing SLCA studies have limitations from a decision-making perspective. The use of simulation and scenarios helps to simplify reality in order to make affordable the product or business reality. However, as Abreu et al. [64] note, ‘it is better to have imperfect evidence that could improve our understanding of the situation than no evidence at all’.

6. Conclusions

Following Dyllick and Muff’s [65] research structure model, the so-call ‘input-process-output’, the rationale of this research is summarized as follows:

- (i)

- ‘Inputs’: What is analyzed in this paper? The social impacts of textile industry along the supply chain from a technical perspective (in RQ1), and their consistency with those that are being identified and managed by textile industry (in RQ2);

- (ii)

- ‘Process’: How are textile industry social impacts analyzed? Through a three-step process:

- -

- Identification of current social impacts managed by the textile companies belonging to different phases of the life cycle (based on the information provided by corporate sustainability reporting and corporate websites)

- -

- Identification of the social hotspots of the textile industry (based on technical analysis: scientific literature, databases and SLCA tools)

- -

- Consistency analysis between both approaches;

- (iii)

- ‘Output’: What is the current situation of social hotspots identification and management of the textile industry analyzed for? For better management of social impacts along the textile industry supply chain and, consequently, for more social sustainability of supply chains.

Concerning RQ1, for the purpose of this paper, it has been highlighted the most relevant social aspect belonging to each of the social category provided by the SLCA carried on based on SHDB. Since these social categories as associated to different stakeholders, these social hotspots analysis covers impacts associated to traditional stakeholders, such as workers and consumers, but also to other less usually considered such as community or vulnerable groups. Social issues related to collective bargaining, wage, toxic and hazards, injuries and fatalities, conflicts, corruption, and sanitary conditions regarding community infrastructure are pointed as the most relevant, especially critical in the fabric production phase and, in a lesser extent, raw material acquisition phase.

Nevertheless, the comparative study of this information with those provided by companies in the different life cycle phases of a textile product (RQ2) has determined that there is a prevalence of inconsistencies between the social hotspots identified for the textile industry and the most relevant social issues managed by textile companies according to the information they provided.

This research could be especially relevant for companies belonging to complex and global supply chains, since it contributes to enhance the knowledge of science-based methodologies for identifying, managing, and reporting their social hotspots. It also contributes to the reflection around the relevance for the decision-makers, including consumers and investors, of the information included in the sustainability reports as they are currently being elaborated. The integration of science-based methodologies such as SLCA in the materiality analysis, could provide useful information regarding the social hotspots under a supply chain perspective.

As Tang [66] remarks, research concerning social issues in the field of operations management differs from traditional operations management field, due to the variety of objectives and stakeholders, and the subjacent context. Future research is necessary to test the robustness of these results in different environments and textile products. Moreover, it should be noted that the analyzed companies are the best companies considering Thomson Reuters ASSET4 database, but results show inconsistencies in social hotspots management. This supports the complexity theory in this field, reinforcing the existence of complexity and temporal and spatial interconnectedness among social, environmental, and economic dimensions which require advancing with holistic research on sustainability in supply chain management, including a multi-tier approach.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems11010008/s1, Table S1: Summary of consistency results.

Author Contributions

M.J.M.-T., M.Á.F.-I., I.F.-F., E.E.-O. and J.M.R.-L. have participated in the conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing original draft preparation, writing review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

More information is available upon request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

This paper is supported by European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 693642, project SMART (Sustainable Market Actors for Responsible Trade). Moreover, the authors would like to thank José Vicente Gisbert-Navarro for their helpful technical support in the design and analysis of the social footprint.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maestrini, V.; Luzzini, D.; Maccarrone, P.; Caniato, F. Supply chain performance measurement systems: A systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamba, C.C.; Chan, P.W.; Sharmina, M. How does social sustainability feature in studies of supply chain management? A review and research agenda. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2017, 22, 522–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Zuluaga-Cardona, L.; Bailey, A.; Rueda, X. Sustainable supply chain management in developing countries: An analysis of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi, P.; Wang, C.; Lim, M.K. Sustainable supply chain modeling and analysis: Past debate, present problems and future challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.L.; Pato, M.V. Supply chain sustainability: A tertiary literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 995–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Zkik, K.; Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.S. Evaluating barriers and solutions for social sustainability adoption in multi-tier supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 3378–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubicz, M.E.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P.F.D.; Carvalho, A. Incorporating social aspects in sustainable supply chains: Trends and future directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.S.; Tang, C.S. Corporate social sustainability in supply chains: A thematic analysis of the literature. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 882–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, P.J.; Przychodzen, W. Social sustainability in supply chains: A review. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 1125–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, F.A.; Chowdhury, I.N.; Klassen, R.D. Social management capabilities of multinational buying firms and their emerging market suppliers: An exploratory study of the clothing industry. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 46, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Gunasekaran, A. Four forces of supply chain social sustainability adoption in emerging economies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 199, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate social performance revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.; Meehan, K.; Richards, A. Corporate social responsibility: The 3C-SR model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2006, 33, 386–398. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, S.; Ahsan, K. Workplace safety compliance implementation challenges in apparel supplier firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, D.; Strähle, J.; Müller, M.; Freise, M. Social sustainable supply chain management in the textile and apparel industry—A literature review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimdars, C.; Haas, A.; Pfister, S. Enhancing comprehensive measurement of social impacts in S-LCA by including environmental and economic aspects. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Zeitz, G.J. Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Svanström, M.; Peters, G.M. Hotspot identification in the clothing industry using social life cycle assessment—Opportunities and challenges of input-output modelling. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Escrig-Olmedo, E. Sustainable supply chain management in a global context: A consistency analysis in the textile industry between environmental management practices at company level and sectoral and global environmental challenges. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 3883–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Agarwal, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. Social sustainability in the supply chain: Construct development and measurement validation. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEusanio, M.; Zamagni, A.; Petti, L. Social sustainability and supply chain management: Methods and tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarshie, A.M.; Salmi, A.; Leuschner, R. Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in supply chains: The state of research in supply chain management and business ethics journals. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2016, 22, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.V.; Schleper, M.C.; Gold, S.; Hall, J.K. The hidden side of sustainable operations and supply chain management: Unanticipated outcomes, trade-offs and tensions. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1749–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelling, N.K.; Sauer, P.C.; Gold, S.; Seuring, S. The role of institutional uncertainty for social sustainability of companies and supply chains. J. Bus. Ethics. 2021, 173, 813–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Shaw, M.; Majumdar, A. Social sustainability tensions in multi-tier supply chain: A systematic literature review towards conceptual framework development. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.; Hall, J. Integrating sustainable development in the supply chain: The case of life cycle assessment in oil and gas and agricultural biotechnology. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, M.; Yasin, M.M. The management of global multi-tier sustainable supply chains: A complexity theory perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, in press. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, S. Impact assessment procedures for sustainable development: A complexity theory perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. Complexity Theory and the Social Sciences: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Gisbert-Navarro, J.V.; Marullo, M.C. An assessment tool to integrate sustainability principles into the global supply chain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawar, S.A.; Seuring, S. Management of social issues in supply chains: A literature review exploring social issues, actions and performance outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M. Measuring corporate environmental performance: A methodology for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske-Janssen, P.; Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. 20 years of performance measurement in sustainable supply chain management–what has been achieved? Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 664–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.B.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Rezaei, J. Assessing the social sustainability of supply chains using Best Worst Method. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuček, L.; Klemeš, J.J.; Kravanja, Z. A review of footprint analysis tools for monitoring impacts on sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 34, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-SETAC. Life Cycle Management. How Business Uses it to Decrease Footprint, Create Opportunities and Make Value Chains More Sustainable. 2009. Available online: www.unep.fr (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Chen, C.; Perry, P.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C. Decent work in the Chinese apparel industry: Comparative analysis of blue-collar and white-collar garment workers. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFC. Global Apparel Supply Chain. International Finance Corporation. 2020. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/industry_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/manufacturing/blogs+and+articles/manufacturing_textiles (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- Arrigo, E. Global Sourcing in Fast Fashion Retailers: Sourcing Locations and Sustainability Considerations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talay, C.; Oxborrow, L.; Brindley, C. How small suppliers deal with the buyer power in asymmetric relationships within the sustainable fashion supply chain. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 117, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, P.C.; Seuring, S. A three-dimensional framework for multi-tier sustainable supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2018, 23, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Torres, S.; Albareda, L.; Rey-Garcia, M.; Seuring, S. Traceability for sustainability–literature review and conceptual framework. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.G.; Zhang, A.; Deakins, E.; Mani, V. Drivers of sub-supplier social sustainability compliance: An emerging economy perspective. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2020, 5, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, V.H.; Gioia, D.A. On the riskiness of lower-tier suppliers: Managing sustainability in supply networks. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 64, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A.; Acquaye, A.A.; Figueroa, A.; Koh, S.L. Sustainable supply chain management and the transition towards a circular economy: Evidence and some applications. Omega 2017, 66, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarachi, D.A.R.; Piekarski, C.M.; Puglieri, F.N.; de Francisco, A.C. Past and future of Social Life Cycle Assessment: Historical evolution and research trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-SETAC. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products. 2009. Available online: http://www.unep.fr/shared/publications/pdf/DTIx1164xPA-guidelines_sLCA.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- UNEP-SETAC. The Methodological Sheets for Sub-categories in Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA). 2013. Available online: www.lifecycleinitiative.org (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Benoit-Norris, C.; Cavan, D.A.; Norris, G. Identifying social impacts in product supply chains: Overview and application of the social hotspot database. Sustainability 2012, 4, 1946–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, N.M.; Vogtländer, J.G. Monetisation of external socio-economic costs of industrial production: A social-LCA-based case of clothing production. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, S.; Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M.; Svanström, M. A life cycle assessment (LCA)-based approach to guiding an industry sector towards sustainability: The case of the Swedish apparel sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzo, P.; Traverso, M.; Salomone, R.; Ioppolo, G. Social life cycle assessment in the textile sector: An Italian case study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit-Norris, C.; Norris, G.C.; Cavan, D.A.; Benoit, P. SHDB 2.1, Supporting Documentation; NewEarth B.: York, ME, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, K.; Chau, C.K.; Yung, W.K. Relevance and feasibility of the existing social LCA methods and case studies from a decision-making perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-SETAC. Hotspots Analysis. An Overarching Methodological Framework and Guidance for Product and Sector Level Application. 2017. Available online: www.lifecycleinitiative.org (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Beton, A.; Dias, D.; Farrant, L.; Gibon, T.; Guern, Y.L.; Desaxce, M.; Perwueltz, A.; Boufateh, I. Environmental Improvement Potential of Textiles (IMPRO-Textiles); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC85895/impro%20textiles_final%20report%20edited_pubsy%20web.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernandez-Izquierdo, M.A.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Gisbert-Navarro, J.V. D5.2 List of Best Practices and KPIs of the Textile Products Life Cycle Public Report, SMART H2020 Project. 2018. Available online: https://www.smart.uio.no/publications/reports/d5.2_final_draft_august-new.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Fritz, M.M.; Schöggl, J.P.; Baumgartner, R.J. Selected sustainability aspects for supply chain data exchange: Towards a supply chain-wide sustainability assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayet, L.; Vermeulen, W.J. Supporting smallholders to access sustainable supply chains: Lessons from the Indian cotton supply chain. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, A.; Herrero-García, N. How corporate social (ir) responsibility in the textile sector is defined, and its impact on ethical sustainability: An analysis of 133 concepts. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubicz, M.E.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P.F.D.; Carvalho, A. Social sustainability management in the apparel supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.; Dreyer, L.C.; Wangel, A. Addressing the effect of social life cycle assessments. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.; David, F.; Crowther, D. Corporate social responsibility in Portugal: Empirical evidence of corporate behaviour. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2005, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the meaning of sustainable business: Introducing a typology from business-as-usual to true business sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 9, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S. Socially responsible supply chains in emerging markets: Some research opportunities. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).