Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Abstract

:1. Introduction

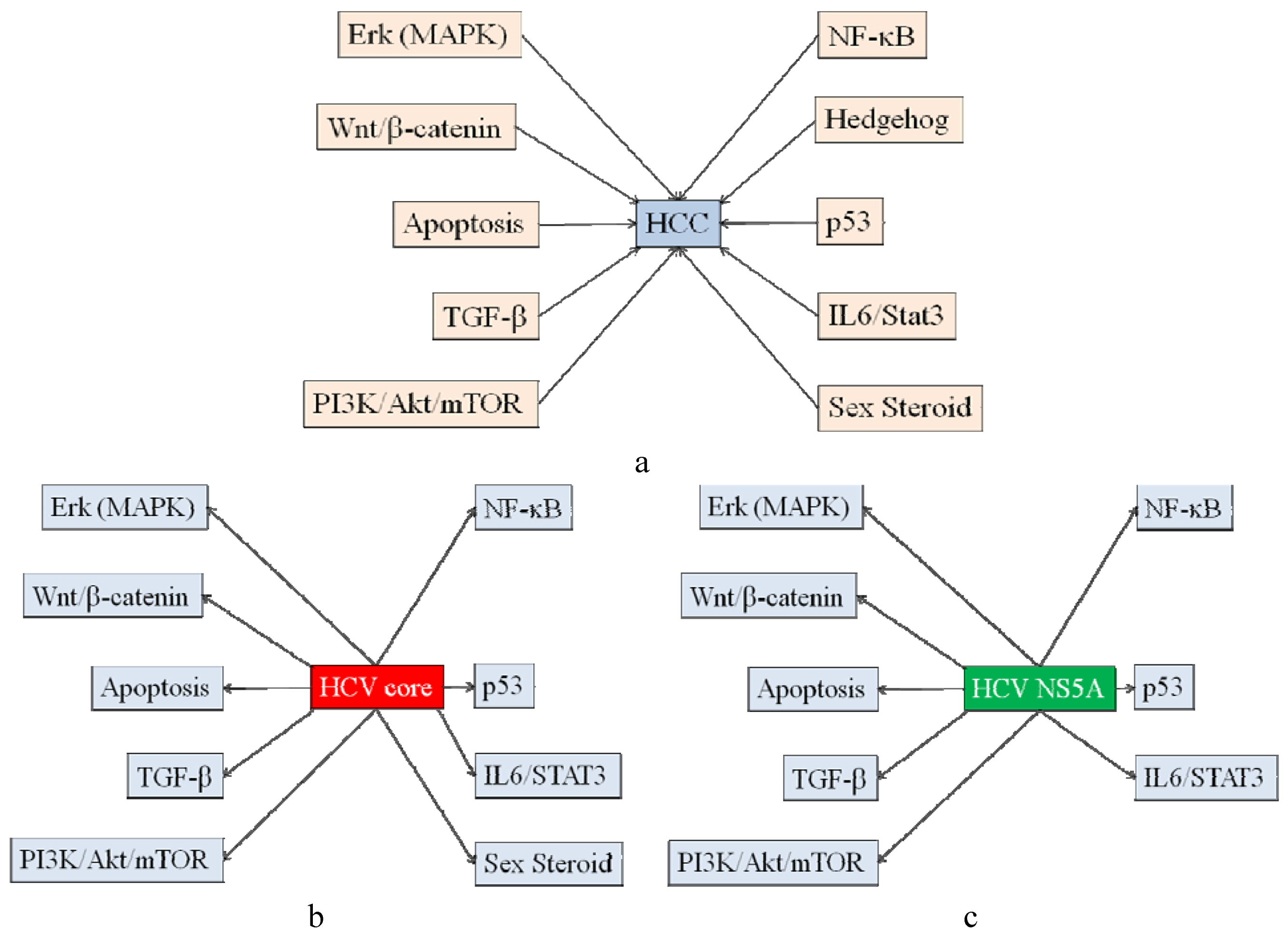

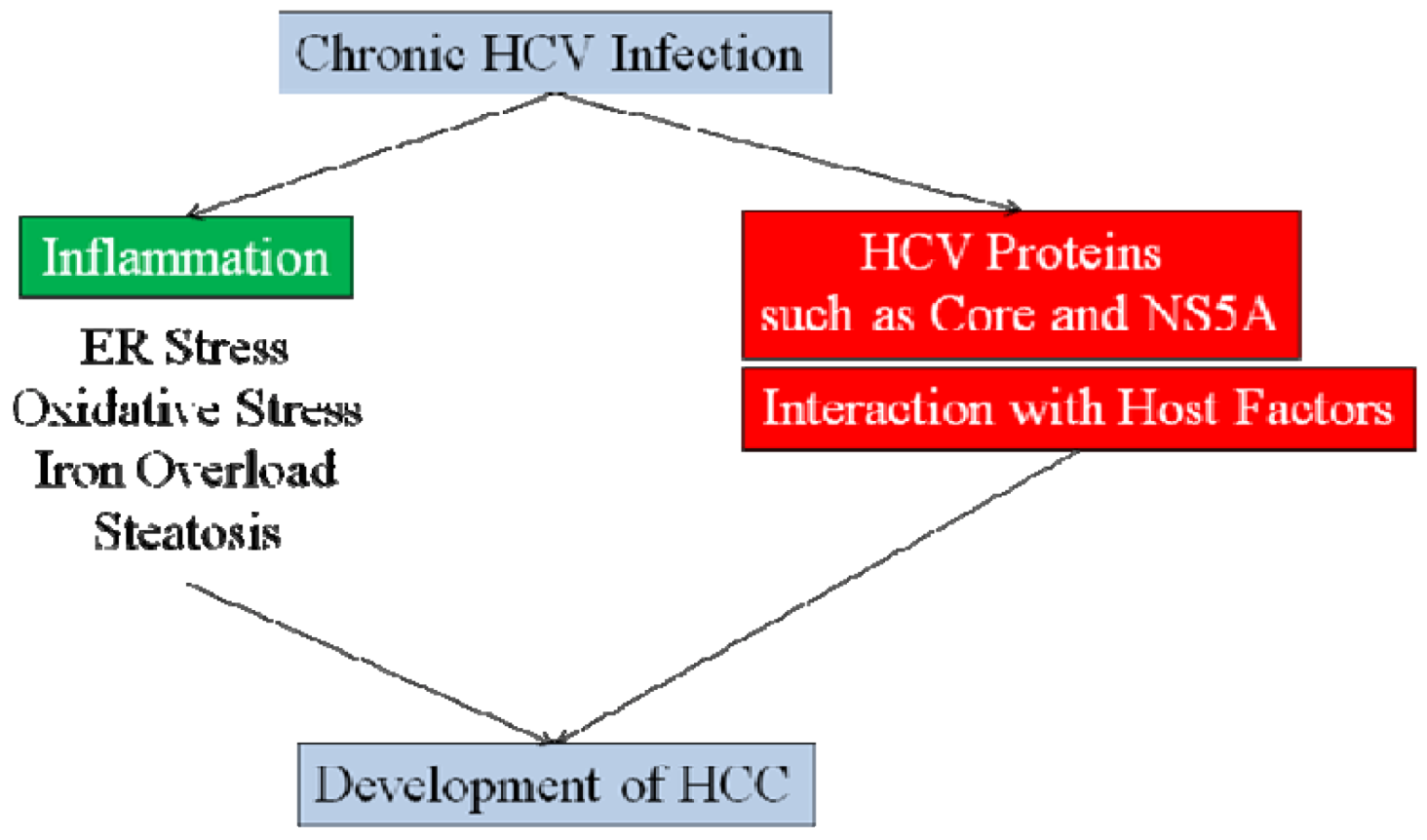

2. Signaling Pathways Affected by HCV Proteins

2.1. Signaling Pathways Involved in Hepatocarcinogenesis

2.2. Signaling Pathways Affected by HCV Core Protein

| HCV protein | Host protein interacted with HCV protein [Reference] | Action |

|---|---|---|

| core | TNF receptor-1 [42], NF-κB [21], TRADD, TRAF [43], pRb [44], p73 [41], 14-3-3epsilon [45], Hsp60 [46], Mcl-1 [47] | pro-apoptosis |

| core | NF-κB [48], p38 MAPK [49], Bcl-x [50], p53 [51], p73 [41], Inhibitor of caspase-activated DNase [52], p21, Bcl-2 [53], Apaf-1, E2F1 [54], Grp78/Bip, Grp94 [55], PML [56], Stat3 [37], cFLIP [22], DR5 [57] | anti-apoptosis |

| NS5A | Bax [58], | pro-apoptosis |

| NS5A | PKR, eIF-2alpha [59], TRADD [60], p53 [61,62], Grb2 [63], PI3K [63,64], NF-κB [65], Bin1 [66], FKBp38 [67,68], calpain cystein protease, Bid [69], Kv2.1 [70], TLR4 [71] | anti-apoptosis |

2.3. Signaling Pathways Affected by HCV NS5A Protein

2.4. Signaling Pathways Affected by other HCV Proteins

2.5. HCV-Associated Inflammation Induces HCC

3. Conclusions

References and Notes

- Hanafiah, K.M.; Groegar, J.; Flaxman, A.D.; Wiersma, S.T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age-specific antibody to hepatitis C virus seroprevalence. Hepatology 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bisceglie, A.M. Hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2012, 26, 34S–38S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Imazeki, F.; Yokosuka, O. New antiviral therapies for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol. Int. 2010, 4, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, M.; Kanda, T.; Yu, M.L.; Yokosuka, O.; Lim, S.G.; Jafri, W.; Tateishi, R.; Hamid, S.S.; Chuang, W.L.; Chutaputti, A.; et al. APASL consensus statements and management algorithms for hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatol. Int. 2012, 6, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kato, N.; Cho, M.J.; Sugiyama, K.; Shimotohno, K. Structure of the 3' terminus of the hepatitis C virus genome. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 3307–3312. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, T.; Steele, R.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Inhibition of intrahepatic gamma interferon production by hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 8463–8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Brown, E.A.; Lemon, S.M. Stability of a stem-loop involving the initiator AUG controls the efficiency of internal initiation of translation on hepatitis C virus RNA. RNA 1996, 2, 955–968. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. Oncogenic potential of hepatitis C virus proteins. Viruses 2010, 2, 2108–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, S.; Yokosuka, O.; Imazeki, F.; Tagawa, M.; Omata, M. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B and C: A prospective study of 251 patients. Hepatology 1995, 21, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarao, K.; Rino, Y.; Ohkawa, S.; Shimizu, A.; Tamai, S.; Miyakawa, K.; Aoki, H.; Imada, T.; Shindo, K.; Okamoto, N.; Totsuka, S. Association between high serum alanine aminotransferase levels and more rapid development and higher rate of incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis. Cancer 1999, 86, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Imazeki, F.; Kanai, F.; Tada, M.; Yokosuka, O.; Omata, M. Signaling pathways involved in molecular carcinogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. In Molecular Aspects of Hepatocellular Carcinoma; Qiao, L., George, J., Li, Y., Yan, X., Eds.; Bentham Science: Oak Park, IL, USA, 2012; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Tsai, W.L.; Chung, R.T. Viral hepatocarcinogenesis. Oncogene 2010, 29, 2309–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.B.; Lagging, L.M.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus core protein cooperates with ras and transforms primary rat embryo fibroblasts to tumorigenic phenotype. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 4438–4443. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, H.; Hayashi, J.; Moriyama, M.; Arakawa, Y.; Hino, O. Hepatitis C virus core protein interacts with 14-3-3 protein and activates the kinase Raf-1. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, J.; Aoki, H.; Kajino, K.; Moriyama, M.; Arakawa, Y.; Hino, O. Hepatitis C virus core protein activates the MAPK/ERK cascade synergistically with tumor promoter TPA, but not with epidermal growth factor or transforming growth factor alpha. Hepatology 2000, 32, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambartolomei, S.; Covone, F.; Levrero, M.; Balsano, C. Sustained activation of the Raf/MEK/Erk pathway in response to EGF in stable cell lines expressing the Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) core protein. Oncogene 2001, 20, 2606–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaziani, A.; Alisi, A.; Sanna, D.; Balsano, C. Role of p38 MAPK and RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) in hepatitis C virus core-dependent nuclear delocalization of cyclin B1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 10983–10989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Kato, J.; Takimoto, R.; Takada, K.; Kawano, Y.; Miyanishi, K.; Kobune, M.; Takayama, T.; Matunaga, T.; Niitsu, Y. Hepatitis C virus core protein promotes proliferation of human hepatoma cells through enhancement of transforming growth factor alpha expression via activation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Gut 2006, 55, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukutomi, T.; Zhou, Y.; Kawai, S.; Eguchi, H.; Wands, J.R.; Li, J. Hepatitis C virus core protein stimulates hepatocyte growth: Correlation with upregulation of wnt-1 expression. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.B.; Meyer, K.; Steele, R.; Shrivastava, A.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Ray, R. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha)-mediated apoptosis by hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 2256–2259. [Google Scholar]

- Marusawa, H.; Hijikata, M.; Chiba, T.; Shimotohno, K. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits Fas- and tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated apoptosis via NF-kappaB activation. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 4713–4720. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, K.; Meyer, K.; Warner, R.; Basu, A.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated apoptosis by a protective effect involving cellular FLICE inhibitory protein. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 4372–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H.; Kato, N.; Otsuka, M.; Goto, T.; Yoshida, H.; Shiratori, Y.; Omata, M. Hepatitis C virus core protein upregulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 transcription. J. Med. Virol. 2004, 72, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavio, N.; Battaglia, S.; Boucreux, D.; Arnulf, B.; Sobesky, R.; Hermine, O.; Brechot, C. Hepatitis C virus core variants isolated from liver tumor but not from adjacent non-tumor tissue interact with Smad3 and inhibit the TGF-beta pathway. Oncogene 2005, 24, 6119–6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, G.; Felmlee, D.J.; Negro, F.; Siddiqui, A. Hepatitis C virus induces proteolytic cleavage of sterol regulatory element binding proteins and stimulates their phosphorylation via oxidative stress. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8122–8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, H.; Moriishi, K.; Moriya, K.; Murata, S.; Tanaka, K.; Suzuki, T.; Miyamura, T.; Koike, K.; Matsuura, Y. Involvement of the PA28gamma-dependent pathway in insulin resistance induced by hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Saito, K.; Ait-Goughoulte, M.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus core protein upregulates serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 and impairs the downstream akt/protein kinase B signaling pathway for insulin resistance. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 2606–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Aoki, H.; Hino, O.; Moriyama, M. HCV core protein promotes heparin binding EGF-like growth factor expression and activates Akt. Hepatol. Res. 2011, 41, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.K.; Shrivastava, S.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus activates the mTOR/S6K1 signaling pathway in inhibiting IRS-1 function for insulin resistance. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 6315–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A.; Manna, S.K.; Ray, R.; Aggarwal, B.B. Ectopic expression of hepatitis C virus core protein differentially regulates nuclear transcription factors. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 9722–9728. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, H.; Kato, N.; Shiratori, Y.; Otsuka, M.; Maeda, S.; Kato, J.; Omata, M. Hepatitis C virus core protein activates nuclear factor kappa B-dependent signaling through tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 16399–16405. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, R.B.; Steele, R.; Basu, A.; Meyer, K.; Majumder, M.; Ghosh, A.K.; Ray, R. Distinct functional role of Hepatitis C virus core protein on NF-kappaB regulation is linked to genomic variation. Virus Res. 2002, 87, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.B.; Steele, R.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R. Transcriptional repression of p53 promoter by hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 10983–10986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.B.; Steele, R.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus core protein represses p21WAF1/Cip1/Sid1 promoter activity. Gene 1998, 208, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, M.; Kato, N.; Lan, K.; Yoshida, H.; Kato, J.; Goto, T.; Shiratori, Y.; Omata, M. Hepatitis C virus core protein enhances p53 function through augmentation of DNA binding affinity and transcriptional ability. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 34122–34130. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, T.; Hanada, T.; Tokuhisa, T.; Kosai, K.; Sata, M.; Kohara, M.; Yoshimura, A. Activation of STAT3 by the hepatitis C virus core protein leads to cellular transformation. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Meyer, K.; Lai, K.K.; Saito, K.; di Bisceglie, A.M.; Grosso, L.E.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. Microarray analyses and molecular profiling of Stat3 signaling pathway induced by hepatitis C virus core protein in human hepatocytes. Virology 2006, 349, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, R.S.; Tosello-Trampont, A.; Nguyen, V.; Mullins, D.W.; Hahn, Y.S. Extracellular hepatitis C virus core protein activates STAT3 in human monocytes/macrophages/dendritic cells via an IL-6 autocrine pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 10847–10855. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, T.; Steele, R.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus core protein augments androgen receptor-mediated signaling. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11066–11072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Goughoulte, M.; Kanda, T.; Meyer, K.; Ryerse, J.S.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus genotype 1a growth and induction of autophagy. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 2241–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisi, A.; Giambartolomei, S.; Cupelli, F.; Merlo, P.; Fontemaggi, G.; Spaziani, A.; Balsano, C. Physical and functional interaction between HCV core protein and the different p73 isoforms. Oncogene 2003, 22, 2573–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Khoshnan, A.; Schneider, R.; Matsumoto, M.; Dennert, G.; Ware, C.; Lai, M.M. Hepatitis C virus core protein binds to the cytoplasmic domain of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 and enhances TNF-induced apoptosis. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 3691–3697. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.J.; Choi, S.H.; Koh, M.S.; Kim, D.J.; Yie, S.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Hwang, S.B. Hepatitis C virus core protein potentiates c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation through a signaling complex involving TRADD and TRAF2. Virus Res. 2001, 74, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Baek, W.; Yang, S.; Chang, J.; Sung, Y.C.; Suh, M. HCV core protein modulates Rb pathway through pRb down-regulation and E2F-1 up-regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001, 1538, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Park, S.O.; Joe, C.O.; Kim, Y.S. Interaction of HCV core protein with 14-3-3epsilon protein releases Bax to activate apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 352, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, W.; Kim, G.W.; Lee, K.H.; Choi, K.Y.; Oh, J.W. Interaction of hepatitis C virus core protein with Hsp60 triggers the production of reactive oxygen species and enhances TNF-alpha-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2009, 279, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd-Ismail, N.K.; Deng, L.; Sukumaran, S.K.; Yu, V.C.; Hotta, H.; Tan, Y.J. The hepatitis C virus core protein contains a BH3 domain that regulates apoptosis through specific interaction with human Mcl-1. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 9993–10006. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, D.I.; Tsai, S.L.; Chen, Y.M.; Chuang, Y.L.; Peng, C.Y.; Sheen, I.S.; Yeh, C.T.; Chang, K.S.; Huang, S.N.; Kuo, G.C.; et al. Activation of nuclear factor kappaB in hepatitis C virus infection: Implications for pathogenesis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology 2000, 31, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, M.; Fujita, T.; Hotta, H. Suppression of serum starvation-induced apoptosis by hepatitis C virus core protein. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2001, 47, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, M.; Kato, N.; Taniguchi, H.; Yoshida, H.; Goto, T.; Shiratori, Y.; Omata, M. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits apoptosis via enhanced Bcl-xL expression. Virology 2002, 296, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. Hepatitis C virus core protein is necessary for the maintenance of immortalized human hepatocytes. Virology 2002, 298, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, R.; Tsutsumi, T.; Suzuki, R.; Otsuka, M.; Aizaki, H.; Sakamoto, S.; Matsuda, M.; Seki, N.; Matsuura, Y.; Miyamura, T.; et al. Antiapoptotic regulation by hepatitis C virus core protein through up-regulation of inhibitor of caspase-activated DNase. Virology 2003, 317, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Ryu, J.; Hwang, S.B.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Park, J. Suppression of ceramide-induced cell death by hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 37, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.; Basu, A.; Saito, K.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus core protein expression in immortalized human hepatocytes induces cytochrome c-independent increase in Apaf-1 and caspase-9 activation for cell death. Virology 2005, 336, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali-Furet, N.L.; Chami, M.; Houel, L.; de Giorgi, F.; Vernejoul, F.; Lagorce, D.; Buscail, L.; Bartenschlager, R.; Ichas, F.; Rizzuto, R.; Paterlini-Brechot, P. Hepatitis C virus core triggers apoptosis in liver cells by inducing ER stress and ER calcium depletion. Oncogene 2005, 24, 4921–4933. [Google Scholar]

- Herzer, K.; Weyer, S.; Krammer, P.H.; Galle, P.R.; Hofmann, T.G. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits tumor suppressor protein promyelocytic leukemia function in human hepatoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 10830–10837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liang, X.; Liu, Y.; Qu, Z.; Gao, L.; Han, L.; Liu, S.; Cui, M.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Hepatitis B virus core protein inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis of hepatocytes by blocking DR5 expression. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.L.; Sheu, M.L.; Yen, S.H. Hepatitis C virus NS5A as a potential viral Bcl-2 homologue interacts with Bax and inhibits apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 107, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, M., Jr.; Kwieciszewski, B.; Dossett, M.; Nakao, H.; Katze, M.G. Antiapoptotic and oncogenic potentials of hepatitis C virus are linked to interferon resistance by viral repression of the PKR protein kinase. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 6506–6516. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder, M.; Ghosh, A.K.; Steele, R.; Zhou, X.Y.; Phillips, N.J.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein impairs TNF-mediated hepatic apoptosis, but not by an anti-FAS antibody, in transgenic mice. Virology 2002, 294, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, K.H.; Sheu, M.L.; Hwang, S.J.; Yen, S.H.; Chen, S.Y.; Wu, J.C.; Wang, Y.J.; Kato, N.; Omata, M.; Chang, F.Y.; et al. HCV NS5A interacts with p53 and inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis. Oncogene 2002, 21, 4801–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.F.; He, B.; Li, N.P.; Ma, J.; Gong, G.Z.; Zhang, M. The oncogenic role of NS5A of hepatitis C virus is mediated by up-regulation of survivin gene expression in the hepatocellular cell through p53 and NF-kappaB pathways. Cell Biol. Int. 2011, 35, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Nakao, H.; Tan, S.L.; Polyak, S.J.; Neddermann, P.; Vijaysri, S.; Jacobs, B.L.; Katze, M.G. Subversion of cell signaling pathways by hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein via interaction with Grb2 and P85 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 9207–9217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, A.; Macdonald, A.; Crowder, K.; Harris, M. The Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein activates a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent survival signaling cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 12232–12241. [Google Scholar]

- Bonte, D.; Francois, C.; Castelain, S.; Wychowski, C.; Dubuisson, J.; Meurs, E.F.; Duverlie, G. Positive effect of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein on viral multiplication. Arch. Virol. 2004, 149, 1353–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, S.K.; Herion, D.; Liang, T.J. The SH3 binding motif of HCV [corrected] NS5A protein interacts with Bin1 and is important for apoptosis and infectivity. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 794–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tong, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Yi, Z.; Pan, T.; Hu, Y.; Xiang, L.; Yuan, Z. Hepatitis C virus non-structural protein NS5A interacts with FKBP38 and inhibits apoptosis in Huh7 hepatoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 4392–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Liang, D.; Tong, W.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z. Hepatitis C virus NS5A activates the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, contributing to cell survival by disrupting the interaction between FK506-binding protein 38 (FKBP38) and mTOR. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 20870–20881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, Y.; Disson, O.; Lerat, H.; Antoine, E.; Biname, F.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Desagher, S.; Lassus, P.; Bioulac-Sage, P.; Hibner, U. Calpain activation by hepatitis C virus proteins inhibits the extrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, C.A.; He, K.; Springer, M.G.; Hartnett, K.A.; Horn, J.P.; Aizenman, E. Regulation of neuronal proapoptotic potassium currents by the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 8865–8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, R.; Kanda, T.; Imazeki, F.; Wu, S.; Nakamoto, S.; Tanaka, T.; Arai, M.; Fujiwara, K.; Saito, K.; Roger, T.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus nonstructural 5A protein inhibits lipopolysaccharide-mediated apoptosis of hepatocytes by decreasing expression of Toll-like receptor 4. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanji, Y.; Kaneko, T.; Satoh, S.; Shimotohno, K. Phosphorylation of hepatitis C virus-encoded nonstructural protein NS5A. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 3980–3986. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, A.; Crowder, K.; Street, A.; McCormick, C.; Saksela, K.; Harris, M. The hepatitis C virus non-structural NS5A protein inhibits activating protein-1 function by perturbing ras-ERK pathway signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 17775–17784. [Google Scholar]

- Milward, A.; Mankouri, J.; Harris, M. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein interacts with beta-catenin and stimulates its transcriptional activity in a phosphoinositide-3 kinase-dependent fashion. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Kang, S.M.; Kang, J.I.; Ahn, B.Y.; Kim, H.; Jung, G.; Choi, K.Y.; Hwang, S.B. Nonstructural 5A protein activates beta-catenin signaling cascades: Implication of hepatitis C virus-induced liver pathogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2009, 51, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, A.; Macdonald, A.; McCormick, C.; Harris, M. Hepatitis C virus NS5A-mediated activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase results in stabilization of cellular beta-catenin and stimulation of beta-catenin-responsive transcription. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 5006–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Majumder, M.; Steele, R.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein protects against TNF-alpha mediated apoptotic cell death. Virus Res. 2000, 67, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Hwang, S.B. Modulation of the transforming growth factor-beta signal transduction pathway by hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 7468–7478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presser, L.D.; Haskett, A.; Waris, G. Hepatitis C virus-induced furin and thrombospondin-1 activate TGF-beta1: Role of TGF-beta1 in HCV replication. Virology 2011, 412, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkari, L.; Gregoire, D.; Floc'h, N.; Moreau, M.; Hernandez, C.; Simonin, Y.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Lassus, P.; Hibner, U. Hepatitis C viral protein NS5A induces EMT and participates in oncogenic transformation of primary hepatocyte precursors. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Xiao, X.; Gong, G. P53 controls hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A-mediated down-regulation of GADD45α expression via the NF-κB and PI3K-Akt pathways. J. Gen. Virol. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Waris, G.; Tanveer, R.; Siddiqui, A. Human hepatitis C virus NS5A protein alters intracellular calcium levels, induces oxidative stress, and activates STAT-3 and NF-kappa B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 9599–9604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.J.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Hwang, S.B.; Lai, M.M. Nonstructural 5A protein of hepatitis C virus modulates tumor necrosis factor alpha-stimulated nuclear factor kappa B activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 13122–13128. [Google Scholar]

- Waris, G.; Tardif, K.D.; Siddiqui, A. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress: Hepatitis C virus induces an ER-nucleus signal transduction pathway and activates NF-kappaB and STAT-3. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 64, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, G.; Livolsi, A.; Imbert, V.; Peyron, J.F.; Siddiqui, A. Hepatitis C virus NS5A and subgenomic replicon activate NF-kappaB via tyrosine phosphorylation of IkappaBalpha and its degradation by calpain protease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 40778–40787. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Steele, R.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein modulates cell cycle regulatory genes and promotes cell growth. J. Gen. Virol. 1999, 80, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Majumder, M.; Steele, R.; Yaciuk, P.; Chrivia, J.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein modulates transcription through a novel cellular transcription factor SRCAP. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 7184–7188. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder, M.; Ghosh, A.K.; Steele, R.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus NS5A physically associates with p53 and regulates p21/waf1 gene expression in a p53-dependent manner. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarcar, B.; Ghosh, A.K.; Steele, R.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus NS5A mediated STAT3 activation requires co-operation of Jak1 kinase. Virology 2004, 322, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.G.; Lee, D.S.; Moon, H.B.; Kim, J.M.; Cho, K.H.; Choi, S.H.; Ha, H.L.; Han, Y.H.; Kim, D.G.; Hwang, S.B.; et al. Non-structural 5A protein of hepatitis C virus induces a range of liver pathology in transgenic mice. J. Pathol. 2009, 219, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.; Steele, R.; Ghosh, A.K.; Zhou, X.Y.; Thornburg, L.; Ray, R.; Phillips, N.J.; Ray, R.B. Expression of hepatitis C virus non-structural 5A protein in the liver of transgenic mice. FEBS Lett. 2003, 555, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A.; Arai, Y.; Hirota, N.; Sato, T.; Ikegami, J.; Koizumi, T.; Hatano, M.; Kohara, M.; Moriyama, T.; Imawari, M.; et al. Hepatitis C virus structural proteins induce liver cell injury in transgenic mice. J. Med. Virol. 1999, 59, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamuro, D.; Furukawa, T.; Takegami, T. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein NS3 transforms NIH 3T3 cells. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 3893–3896. [Google Scholar]

- Zemel, R.; Gerechet, S.; Greif, H.; Bachmatove, L.; Birk, Y.; Golan-Goldhirsh, A.; Kunin, M.; Berdichevsky, Y.; Benhar, I.; Tur-Kaspa, R. Cell transformation induced by hepatitis C virus NS3 serine protease. J. Viral Hepat. 2001, 8, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Ghozlan, H.; Abdel-Kader, O. Activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway is essential for the stimulation of hepatitis C virus (HCV) non-structural protein 3 (NS3)-mediated cell growth. Virology 2005, 333, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Nagano-Fujii, M.; Deng, L.; Ishido, S.; Sada, K.; Hotta, H. Single-point mutations of hepatitis C virus NS3 that impair p53 interaction and anti-apoptotic activity of NS3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 340, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, C.S.; Seol, S.K.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.; Song, Y.L.; Bartenschlager, R.; Jang, S.K. E2 of hepatitis C virus inhibits apoptosis. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 8226–8235. [Google Scholar]

- Foy, E.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Sumpter, R., Jr.; Ikeda, M.; Lemon, S.M.; Gale, M., Jr. Regulation of interferon regulatory factor-3 by the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Science 2003, 300, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, M.; Kato, N.; Otsuka, M.; Shao, R.X.; Taniguchi, H.; Kawabe, T.; Omata, M. Interferon-beta is activated by hepatitis C virus NS5B and inhibited by NS4A, NS4B, and NS5A. Hepatol. Int. 2007, 1, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuzaki, R.; Tateishi, R.; Yoshida, H.; Goto, E.; Sato, T.; Ohki, T.; Imamura, J.; Goto, T.; Kanai, F.; Kato, N.; et al. Prospective risk assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma development in patients with chronic hepatitis C by transient elastography. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1954–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahasrabuddhe, V.V.; Gunja, M.Z.; Graubard, B.I.; Trabert, B.; Schwartz., L.M.; Park, Y.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Freedman, N.D.; McGlynn, K.A. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use, Chronic Liver Disease, and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 1808–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuda, M.; Kondoh, N.; Imazeki, N.; Tanaka, K.; Okada, T.; Mori, K.; Hada, A.; Arai, M.; Wakatsuki, T.; Matsubara, O.; et al. Activation of the ATF6, XBP1 and grp78 genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma: A possible involvement of the ER stress pathway in hepatocarcinogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2003, 38, 605–614. [Google Scholar]

- Asselah, T.; Bieche, I.; Mansouri, A.; Laurendeau, I.; Cazals-Hatem, D.; Feldmann, G.; Bedossa, P.; Paradis, V.; Martinot-Peignoux, M.; Lebrec, D.; et al. In vivo hepatic endoplasmic reticulum stress in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Pathol. 2010, 221, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merquiol, E.; Uzi, D.; Mueller, T.; Goldenberg, D.; Nahmias, Y.; Xavier, R.J.; Tirosh, B.; Shibolet, O. HCV causes chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress leading to adaptation and interference with the unfolded protein response. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24660. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, P.Y.; Chen, S.S. Hepatitis C virus and cellular stress response: Implications to molecular pathogenesis of liver diseases. Viruses 2012, 4, 2251–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Kang, R.; Wang, J.; Luo, G.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Z. Hepatitis C virus inhibits AKT-tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), the mechanistic target of rapamycin (MTOR) pathway, through endoplasmic reticulum stress to induce autophagy. Autophagy 2012, 9, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama-Kohara, K. Role of oxidative stress in hepatocarcinogenesis induced by hepatitis C virus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 15271–15278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, J.; Kobune, M.; Nakamura, T.; Kuroiwa, G.; Takada, K.; Takimoto, R.; Sato, Y.; Fujikawa, K.; Takahashi, M.; Takayama, T.; et al. Normalization of elevated hepatic 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine levels in chronic hepatitis C patients by phlebotomy and low iron diet. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 8697–8702. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, J.; Miyanishi, K.; Kobune, M.; Nakamura, T.; Takada, K.; Takimoto, R.; Kawano, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Takahashi, M.; Sato, Y.; et al. Long-term phlebotomy with low-iron diet therapy lowers risk of development of hepatocellular carcinoma from chronic hepatitis C. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 42, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Trinh, T.L.; Dong, H.; Keith, R.; Nelson, D.; Liu, C. Iron regulator hepcidin exhibits antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus. PLoS One 2012, 7, e46631. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Elmonem, E.; Tharwa, S.; Farag, M.A.; Fawzy, A.; El Shinnawy, S.F.; Suliman, S. Hepcidin mRNA level as a parameter of disease progression in chronic hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Egypt. Natl. Canc. Inst. 2009, 21, 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen, U.; Arkkila, P.E.; Karkkainen, P.; Farkkila, M.A. Effect of steatosis and inflammation on liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009, 29, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiDonato, J.A.; Mercurio, F.; Karin, M. NF-kappaB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 2012, 246, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanda, T.; Yokosuka, O.; Omata, M. Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology 2013, 2, 304-316. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010304

Kanda T, Yokosuka O, Omata M. Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology. 2013; 2(1):304-316. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010304

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanda, Tatsuo, Osamu Yokosuka, and Masao Omata. 2013. "Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma" Biology 2, no. 1: 304-316. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010304

APA StyleKanda, T., Yokosuka, O., & Omata, M. (2013). Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology, 2(1), 304-316. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010304