Integrated Oxygen Consumption Rate, Energy Metabolism, and Transcriptome Analysis Reveal the Heat Sensitivity of Wild Amur Grayling (Thymallus grubii) Under Acute Warming

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

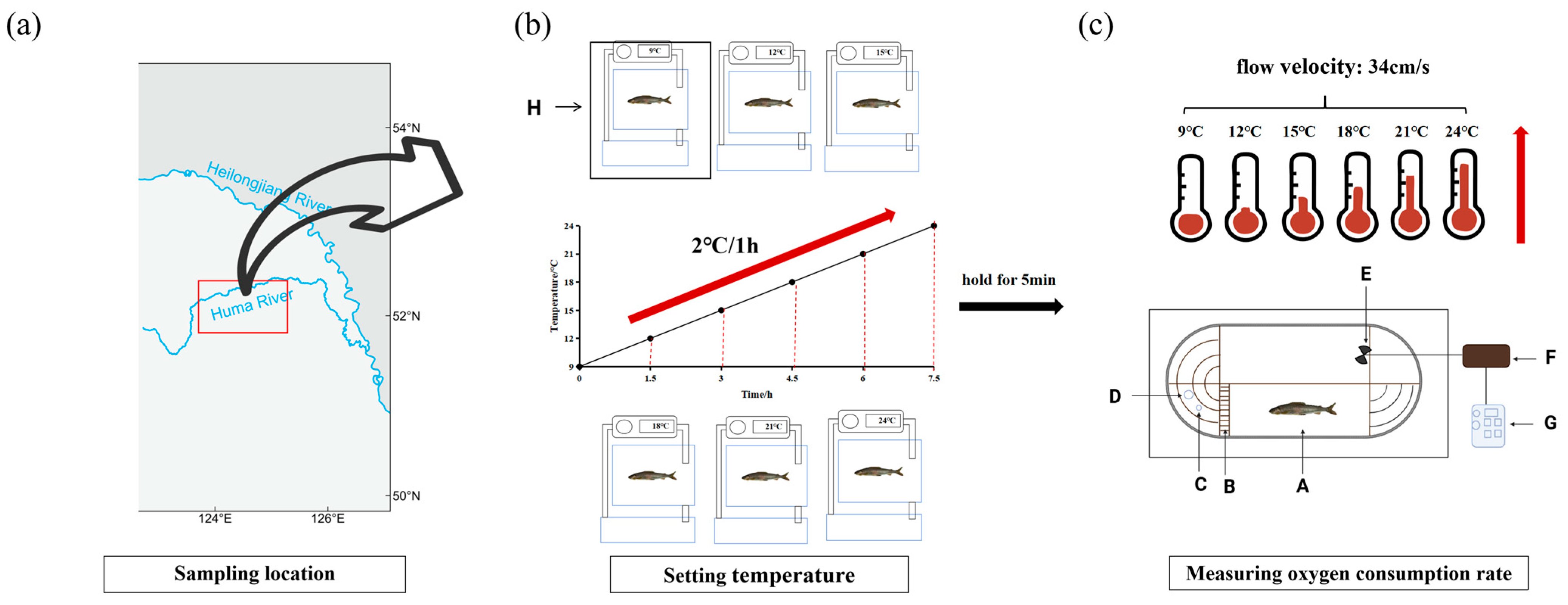

2.1. Experimental Animal Preparation and Breeding

2.2. Experimental Facility Overview

2.3. Experiment Designs

2.4. Determination of the Enzyme Activity of Glucose Metabolism, the Content of Substances of Energy Metabolism, and Hemoglobin Concentration Analysis

2.5. Project for the Construction of cDNA Libraries and Transcriptome Sequencing

2.6. Quality Control, De Novo Assembly, and Annotation

2.7. Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) Identification

2.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Verification

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

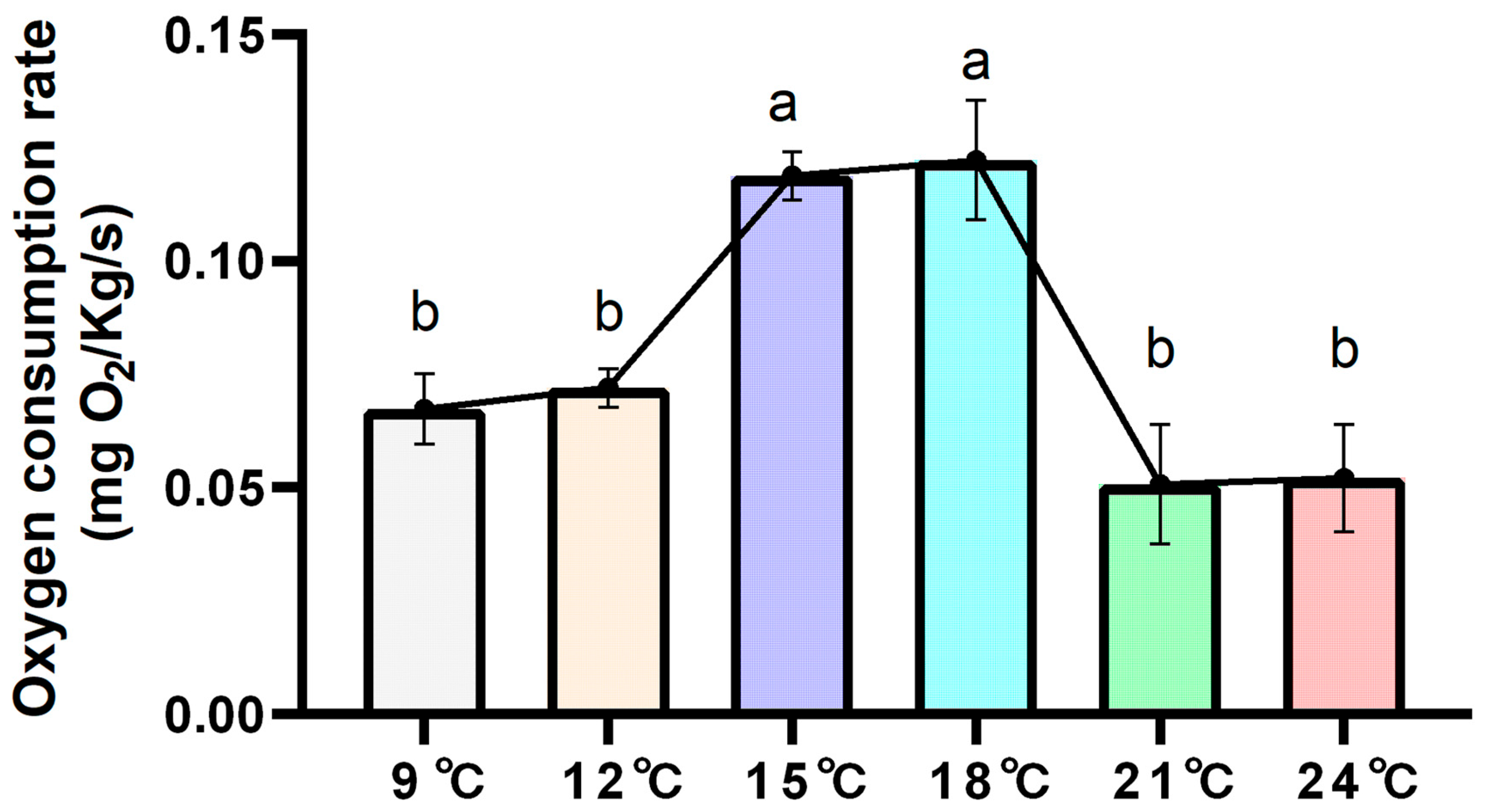

3.1. Oxygen Consumption Rates at Different Temperatures

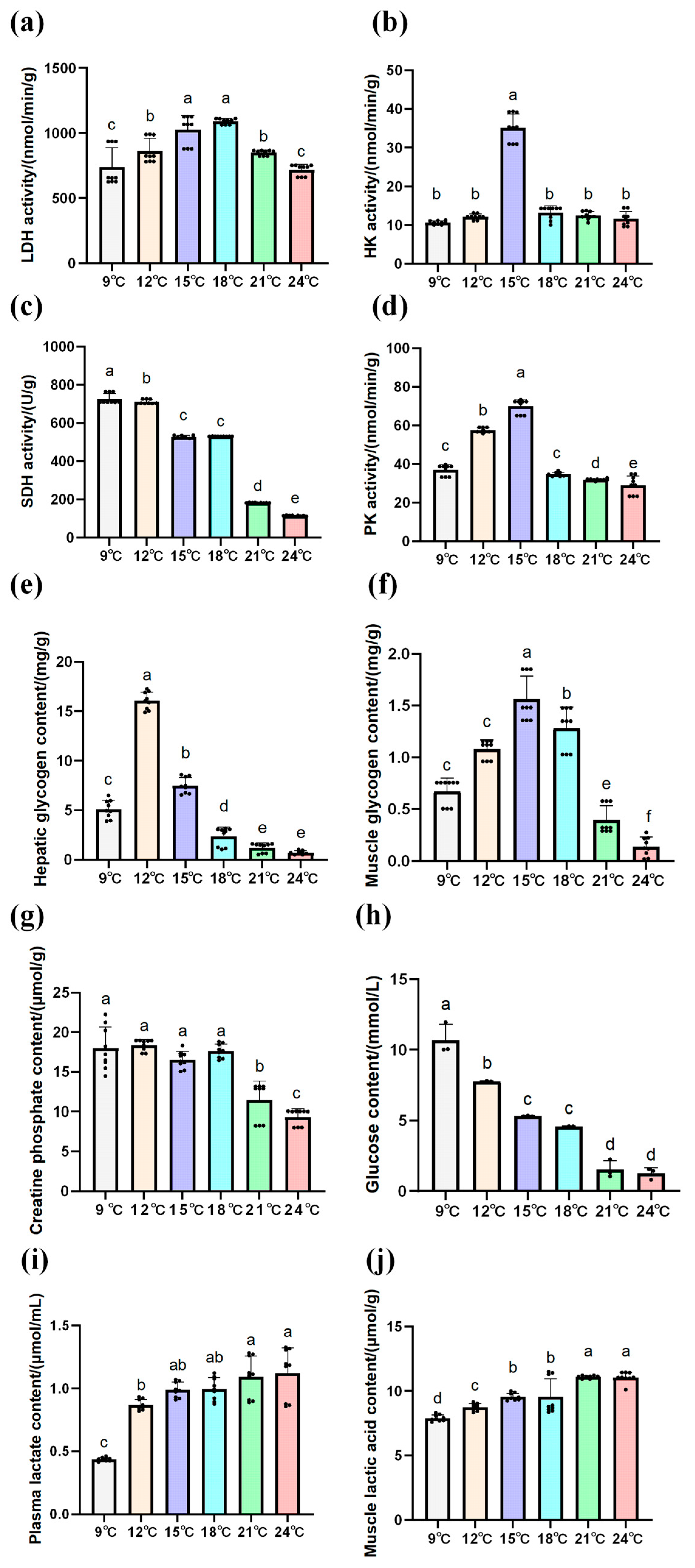

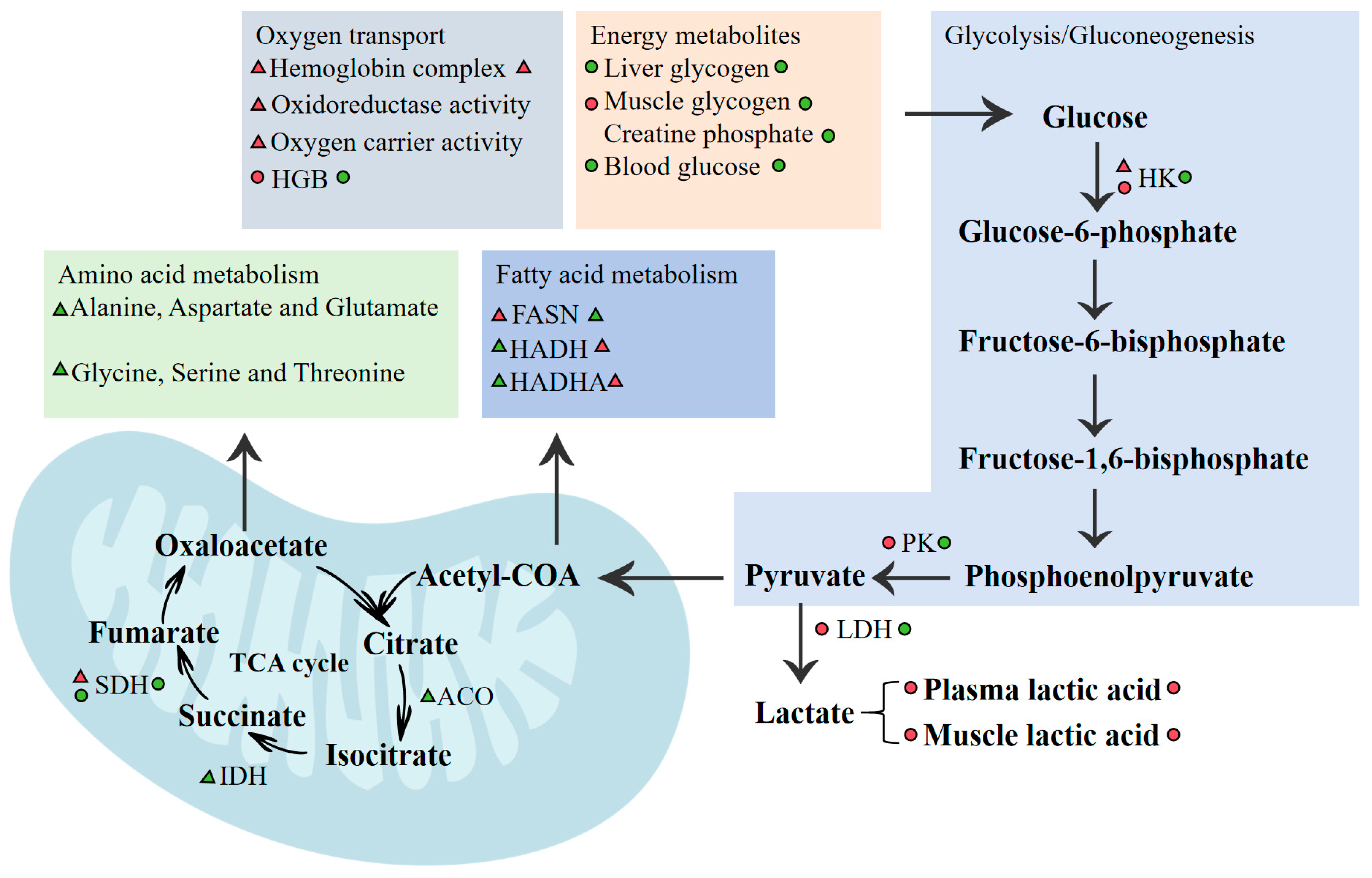

3.2. Effects of Temperature Changes on Physiological Indexes of Amur Grayling

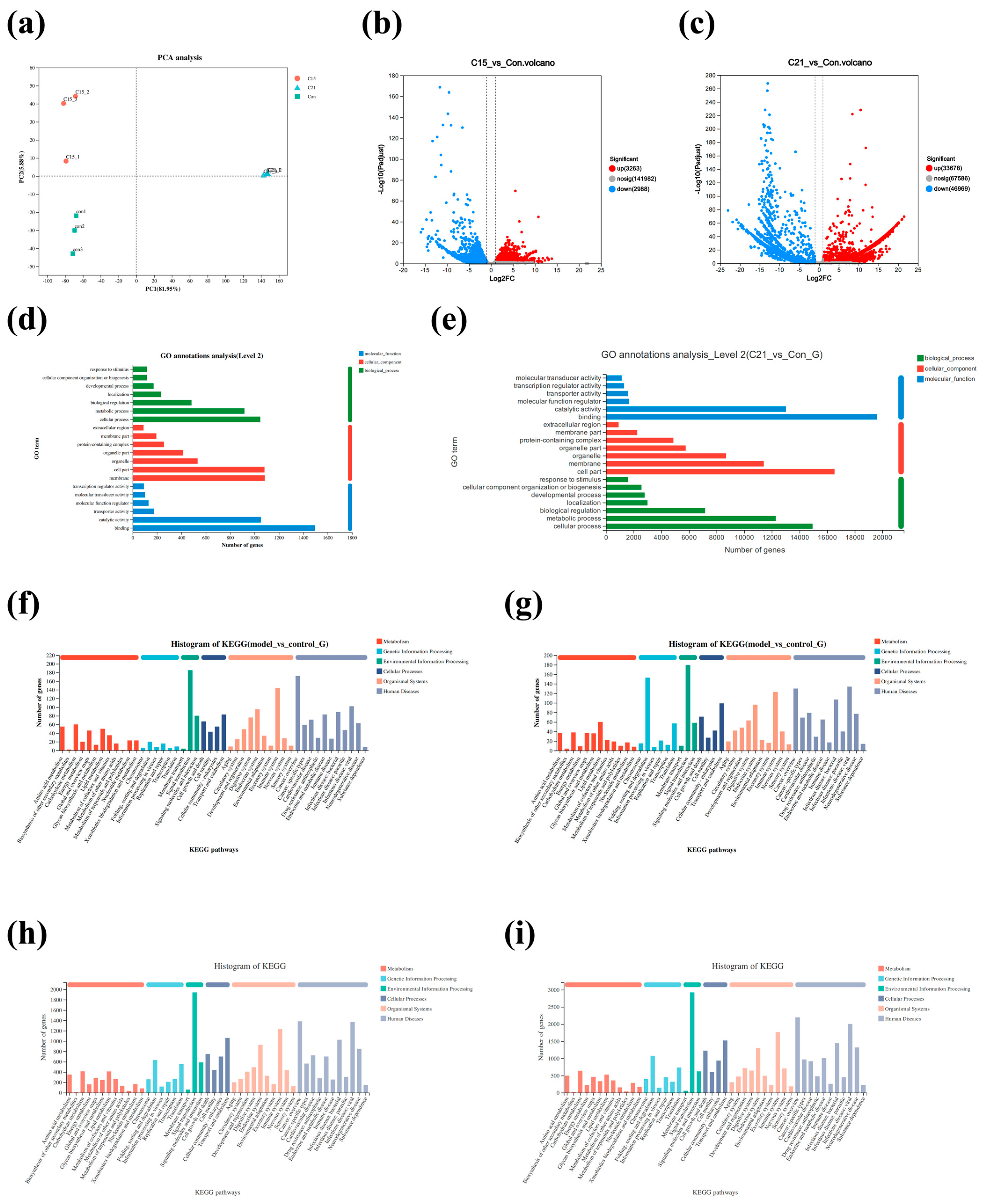

3.3. Changes in Transcriptome Profile Induced by Temperature Stress

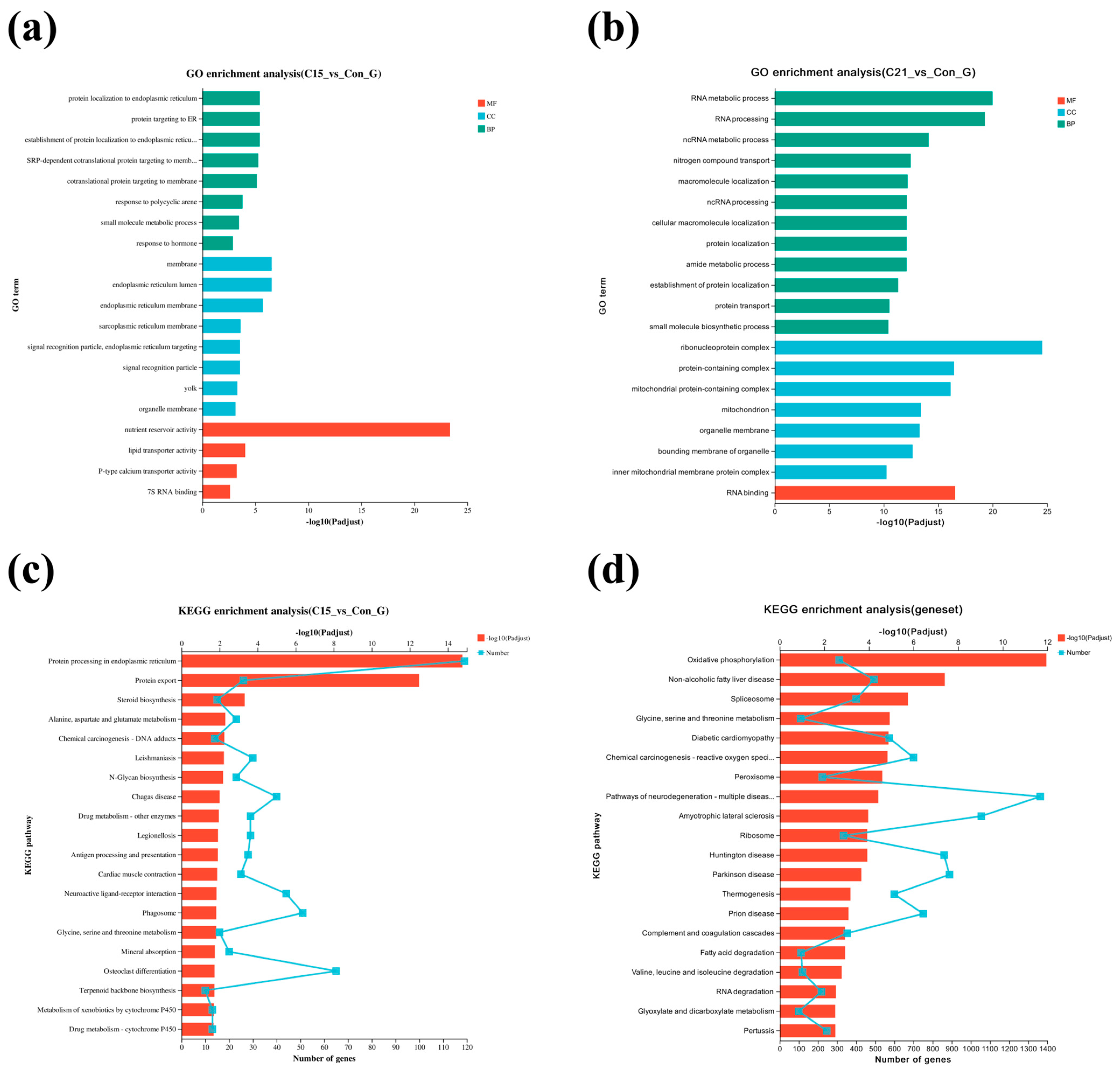

3.4. GO Enrichment and KEGG Pathway Analysis for DEGs

3.5. Validation of RNA-Seq Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pörtner, H.O.; Peck, M.A. Climate change effects on fishes and fisheries: Towards a cause-and-effect understanding. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 77, 1745–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Marín, L.A.; Rokaya, P.; Sanyal, P.R.; Sereda, J.; Lindenschmidt, K.E. Changes in stream flow and water temperature affect fish habitat in the Athabasca River basin in the context of climate change. Ecol. Model. 2019, 407, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Long, Y.; Shi, L.; Ren, J.; Yan, J.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Cui, Z. Transcriptomic profiling revealed key signaling pathways for cold tolerance and acclimation of two carp species. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.M.; Elliott, J. Temperature requirements of Atlantic salmon Salmo salar, brown trout Salmo trutta and Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus: Predicting the effects of climate change. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 77, 1793–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Ren, W.; Zheng, S.; Ren, Y. Histological, immune, and intestine microbiota responses of the intestine of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to high temperature stress. Aquaculture 2024, 582, 740465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Ma, B.; Zhang, B.; He, Y.; Wang, Y. Disturbance of oxidation/antioxidant status and histopathological damage in tsinling lenok trout under acute thermal stress. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Prisco, G.; Verde, C. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the evolutionary adaptations of polar fish. In Life in Extreme Environments; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 385–397. [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre, S.; Mckenzie, D.J.; Nilsson, G.E. Models projecting the fate of fish populations under climate change need to be based on valid physiological mechanisms. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 34493459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brett, J.R. The respiratory metabolism and swimming performance of young sockeye salmon. J. Fish. Res. BOARD Can. 1964, 21, 1183–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matern, S.A.; Cech, J.J.; Hopkins, T.E. Diel movements of bat rays, Myliobatis californica, in Tomales Bay, California: Evidence for behavioral thermoregulation? Environ. Biol. Fishes 2000, 58, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodianitskyi, O.; Potrokhov, O.; Zinkovskyi, O.; Khudiiash, Y.; Prychepa, M. Effects of increasing water temperature and decreasing water oxygen concentration on enzyme activity in developing carp embryos (Cyprinus carpio). Fish. Aquat. Life 2021, 29, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.; Woo, N. Influence of dietary carbohydrate level on endocrine status and hepatic carbohydrate metabolism in the marine fish Sparus sarba. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 38, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Q.; Ding, D.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Li, R.; Yan, Y.; He, J. Effect of potato glycoside alkaloids on energy metabolism of Fusarium solani. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akila, P.; Asaikumar, L.; Vennila, L. Chlorogenic acid ameliorates isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in rats by stabilizing mitochondrial and lysosomal enzymes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 85, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granchi, C.; Bertini, S.; Macchia, M.; Minutolo, F. Inhibitors of lactate dehydrogenase isoforms and their therapeutic potentials. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 672–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zikos, A.; Seale, A.; Lerner, D.; Grau, E.; Korsmeyer, K. Effects of salinity on metabolic rate and branchial expression of genes involved in ion transport and metabolism in Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2014, 178, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wedekind, C.; Kueng, C. Shift of spawning season and effects of climate warming on developmental stages of a grayling (Salmonidae). Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Longoria, J.A.; Gaylord, G.; Andrews, L.; Powell, M. Effect of temperature on growth, survival, and chronic stress responses of Arctic Grayling juveniles. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2024, 153, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykänen, M.; Huusko, A.; Mäki-Petäys, A. Seasonal changes in the habitat use and movements of adult European grayling in a large subarctic river. J. Fish Biol. 2001, 58, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, A.L.; Haugen, T.O.; Vøllestad, L.A. Distribution and movement of European grayling in a subarctic lake revealed by acoustic telemetry. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2014, 23, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, C.; Unfer, G. Spawning activity of European grayling (Thymallus thymallus) driven by interdaily water temperature variations: Case study Gr. Mühl River/Austria. River Res. Appl. 2021, 37, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, B.; Jonsson, N. A review of the likely effects of climate change on anadromous Atlantic salmon Salmo salar and brown trout Salmo trutta, with particular reference to water temperature and flow. J. Fish Biol. 2009, 75, 2381–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehanen, T.; Huusko, A.; Yrjänä, T.; Lahti, M.; Mäki-Petäys, A. Habitat preference by grayling (Thymallus thymallus) in an artificially modified, hydropeaking riverbed: A contribution to understand the effectiveness of habitat enhancement measures. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2003, 19, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, G.; Wang, Q. China Red Data Book of Endangered Animals; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1998; pp. 204–206. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Liang, X.; Ma, B.; Song, D. Occurrence of Amur grayling (Thymallus grubii grubii Dybowski, 1869) in the Amur River. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2013, 29, 666–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Yu, G.; Miao, Y.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of Meteorological Element Variation Characteristics in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin. Water 2024, 16, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.L.; Xia, Z.Q.; Li, J.K.; Cai, T. Climate change characteristics of Amur River. Water Sci. Eng. 2013, 6, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, S.J.; Isaak, D.J.; Luce, C.H.; Neville, H.M.; Fausch, K.D.; Dunham, J.B.; Dauwalter, D.C.; Young, M.K.; Elsner, M.M.; Rieman, B.E.; et al. Flow regime, temperature, and biotic interactions drive differential declines of trout species under climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14175–14180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Chen, J.H.; Johnson, D.; Tu, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.P. Effect of body length on swimming capability and vertical slot fishway design. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Li, Y.; Zhu, G.; Peng, W.; E, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, B. The Effects of Water Flow Speed on Swimming Capacity and Energy Metabolism in Adult Amur Grayling (Thymallus grubii). Fishes 2024, 9, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnyukova, T.; Lushchak, O.; Storey, K.; Lushchak, V. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense responses by goldfish tissues to acute change of temperature from 3 to 23 °C. J. Therm. Biol. 2007, 32, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Xue, L. Liver transcriptome sequencing and de novo annotation of the large yellow croaker (Larimichthy crocea) under heat and cold stress. Mar. Geonomics 2015, 25, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J.; Nicieza, A. Temperature, metabolic rate, and constraints on locomotor performance in ectotherm vertebrates. Funct. Ecol. 2006, 20, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, E.; Svendsen, M.; Steffensen, J. The combined effect of body size and temperature on oxygen consumption rates and the size-dependency of preferred temperature in European perch Perca fluviatilis. J. Fish. Biol. 2020, 97, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, C.E.; Cech, J.J. Effects of environmental hypoxia on oxygen consumption rate and swimming activity in juvenile white sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanus, in relation to temperature and life intervals. Environ. Biol. Fishes 1997, 50, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waraniak, J.; Batchelor, S.; Wagner, T.; Keagy, J. Landscape transcriptomic analysis detects thermal stress responses and potential adaptive variation in wild brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) during successive heatwaves. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 969, 178960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahnsteiner, F. Hematological adaptations in diploid and triploid Salvelinus fontinalis and diploid Oncorhynchus mykiss (Salmonidei, Teleostei) in response to long-term exposure to elevated temperature. J. Therm. Biol. 2022, 106, 103256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, H.J.; Kim, A.; Kim, N.; Lee, Y.; Kim, D.H. Multi-omics analysis provides novel insight into immuno-physiological pathways and development of thermal resistance in rainbow trout exposed to acute thermal stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Shi, H.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Label-free quantification of protein expression in the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in response to short-term exposure to heat stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2019, 30, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, A.C.; Borges, M.E.; Herrerias, T.; Kandalski, P.K.; Marins, E.d.A.; Viana, D.; de Souza, M.R.D.P.; Daloski, L.O.D.C.; Donatti, L. Effect of gradual temperature increase on the carbohydrate energy metabolism responses of the Antarctic fish Notothenia rossii. Mar. Environ. Res. 2019, 150, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, E. Variation in metabolic enzymatic activity in white muscle and liver of blue tilapia, Oreochromis aureus, in response to long-term thermal acclimatization. Chin. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2015, 33, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, R.; Van-Herwerden, L.; Smith-Keune, C.; Jerry, D. Comparative characterization of a temperature responsive gene (lactate dehydrogenase-B, ldh-b) in two congeneric tropical fish, Lates calcarifer and Lates niloticus. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 5, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- He, W.; Cao, Z.; Fu, S. Effect of temperature on hypoxia tolerance and underlying biochemical mechanism in two juvenile cyprinids with different hypoxia sensitivity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2014, 187, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas, B.; Conceição, L.E.; Aragão, C.; Martos, J.A.; Ruiz-Jarabo, I.; Mancera, J.M.; Afonso, A. Physiological responses of Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis Kaup, 1858) after stress challenge: Effects on non-specific immune parameters, plasma free amino acids and energy metabolism. Aquaculture 2011, 316, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, H.; Yang, M. Metabolomic Effects of the Dietary Inclusion of Hermetia illucens Larva Meal in Tilapia. Metabolites 2022, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ke, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Lai, J.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Li, H.; Du, J.; Li, Q. Integrated analysis about the effects of heat stress on physiological responses and energy metabolism in Gymnocypris chilianensis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, I.D. The effect of temperature on protein metabolism in fish: The possible consequences for wild Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) stocks in Europe as a result of global warming. In Global Warming: Implications for Freshwater and Marine Fish; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dettleff, P.; Zuloaga, R.; Fuentes, M.; Gonzalez, P.; Aedo, J.; Estrada, J.M.; Molina, A.; Valdés, J.A. High-temperature stress effect on the red cusk-eel (geypterus chilensis) liver: Transcriptional modulation and oxidative stress damage. Biology 2022, 11, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ren, M.; Liang, H.; Ge, X.; Xu, H.; Wu, L. Transcriptome analysis of the effect of high-temperature on nutrient metabolism in juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Gene 2022, 809, 146035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, S.; Bagatto, B.B.; DeMille, M.D.; Learner, A.L.; LeBlanc, D.L.; Marks, C.M.; Ong, K.O.; Parker, J.P.; Templeman, N.T.; Tufts, B.L.T.; et al. Metabolism, nitrogen excretion, and heat shock proteins in the central mudminnow (Umbra limi), a facultative air-breathing fish living in a variable environment. Can. J. Zool. 2010, 88, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, J.; Wood, C. Brain and gills as internal and external ammonia sensing organs for ventilatory control in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Compar. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integrat. Physiol. 2021, 254, 110896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullgren, A.; Jutfelt, F.; Fontanillas, R.; Sundell, K.; Samuelsson, L.; Wiklander, K.; Kling, P.; Koppe, W.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Björnsson, B.T.; et al. The impact of temperature on the metabolome and endocrine metabolic signals in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2013, 164, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viant, M.R.; Werner, I.; Rosenblum, E.S.; Gantner, A.S.; Tjeerdema, R.S.; Johnson, M.L. Correlation between heat-shock protein induction and reduced metabolic condition in juvenile steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) chronically exposed to elevated temperature. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 29, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.D.; Lewis, J.B.; Cott, P.A.; Baker, L.F.; Mochnacz, N.J.; Swanson, H.K.; Poesch, M.S. Habitat use by fluvial Arctic grayling (Thymallus arcticus) across life stages in northern mountain streams. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2023, 106, 1001–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.A.; Helmy, O.; Holsinger, L.M.; Young, M.K. Evidence of climate-induced range contractions in bull trout Salvelinus confluentus in a Rocky Mountain watershed, USA. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieman, B.E.; Isaak, D.; Adams, S.; Horan, D.; Nagel, D.; Luce, C.; Myers, D. Anticipated climate warming effects on bull trout habitats and populations across the interior Columbia River basin. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2007, 136, 1552–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahel, F.J.; Keleher, C.J.; Anderson, J.L. Potential habitat loss and population fragmentation for cold water fish in the North Platte River drainage of the Rocky Mountains: Response to climate warming. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1996, 41, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, D.R.; Robinson, J.M.; Josephson, D.C.; Sheldon, D.R.; Kraft, C.E. Elevated summer temperatures delay spawning and reduce redd construction for resident brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Navarro, A.; Gillingham, P.K.; Britton, J.R. Predicting shifts in the climate space of freshwater fishes in Great Britain due to climate change. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 203, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Water Temperature | 9 °C | 12 °C | 15 °C | 18 °C | 21 °C | 24 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age/year | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| sample size | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| wet weight/g | 50.43 ± 5.21 a | 55.84 ± 7.98 a | 54.39 ± 7.41 a | 54.67 ± 7.85 a | 53.93 ± 3.30 a | 54.92 ± 4.96 a |

| body length/cm | 16.98 ± 0.47 a | 17.00 ± 0.47 a | 16.91 ± 0.30 a | 17.03 ± 0.44 a | 17.16 ± 0.38 a | 17.13 ± 0.30 a |

| Temperature/°C | Temperature Coefficient Q10 |

|---|---|

| 9–12 | 1.25 |

| 12–15 | 5.30 |

| 15–18 | 1.10 |

| 18–21 | 0.05 |

| 21–24 | 1.09 |

| Water Temperature | 9 °C | 12 °C | 15 °C | 18 °C | 21 °C | 24 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGB (g/L) | 96.07 ± 6.84 c | 102.62 ± 10.43 c | 117 ± 9.12 b | 127.78 ± 3.49 a | 37.9 ± 6.14 d | 42.29 ± 9.52 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhai, C.; Wang, Z.; Bai, L.; Ma, B. Integrated Oxygen Consumption Rate, Energy Metabolism, and Transcriptome Analysis Reveal the Heat Sensitivity of Wild Amur Grayling (Thymallus grubii) Under Acute Warming. Biology 2025, 14, 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121718

Zhai C, Wang Z, Bai L, Ma B. Integrated Oxygen Consumption Rate, Energy Metabolism, and Transcriptome Analysis Reveal the Heat Sensitivity of Wild Amur Grayling (Thymallus grubii) Under Acute Warming. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121718

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhai, Cunhua, Ziyang Wang, Luye Bai, and Bo Ma. 2025. "Integrated Oxygen Consumption Rate, Energy Metabolism, and Transcriptome Analysis Reveal the Heat Sensitivity of Wild Amur Grayling (Thymallus grubii) Under Acute Warming" Biology 14, no. 12: 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121718

APA StyleZhai, C., Wang, Z., Bai, L., & Ma, B. (2025). Integrated Oxygen Consumption Rate, Energy Metabolism, and Transcriptome Analysis Reveal the Heat Sensitivity of Wild Amur Grayling (Thymallus grubii) Under Acute Warming. Biology, 14(12), 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121718