Adenoviral Vectors for Gene Therapy of Hereditary Diseases

Simple Summary

Abstract

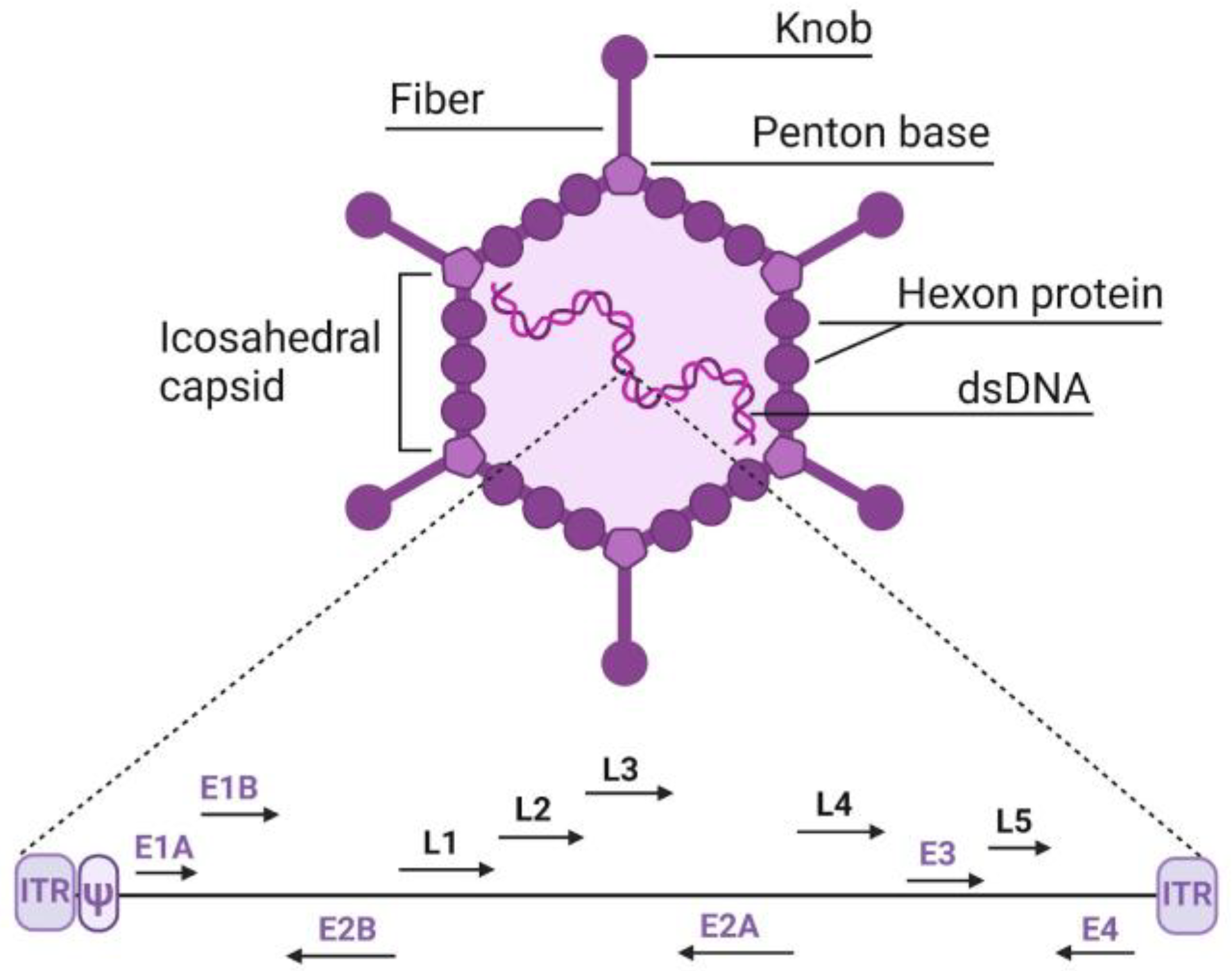

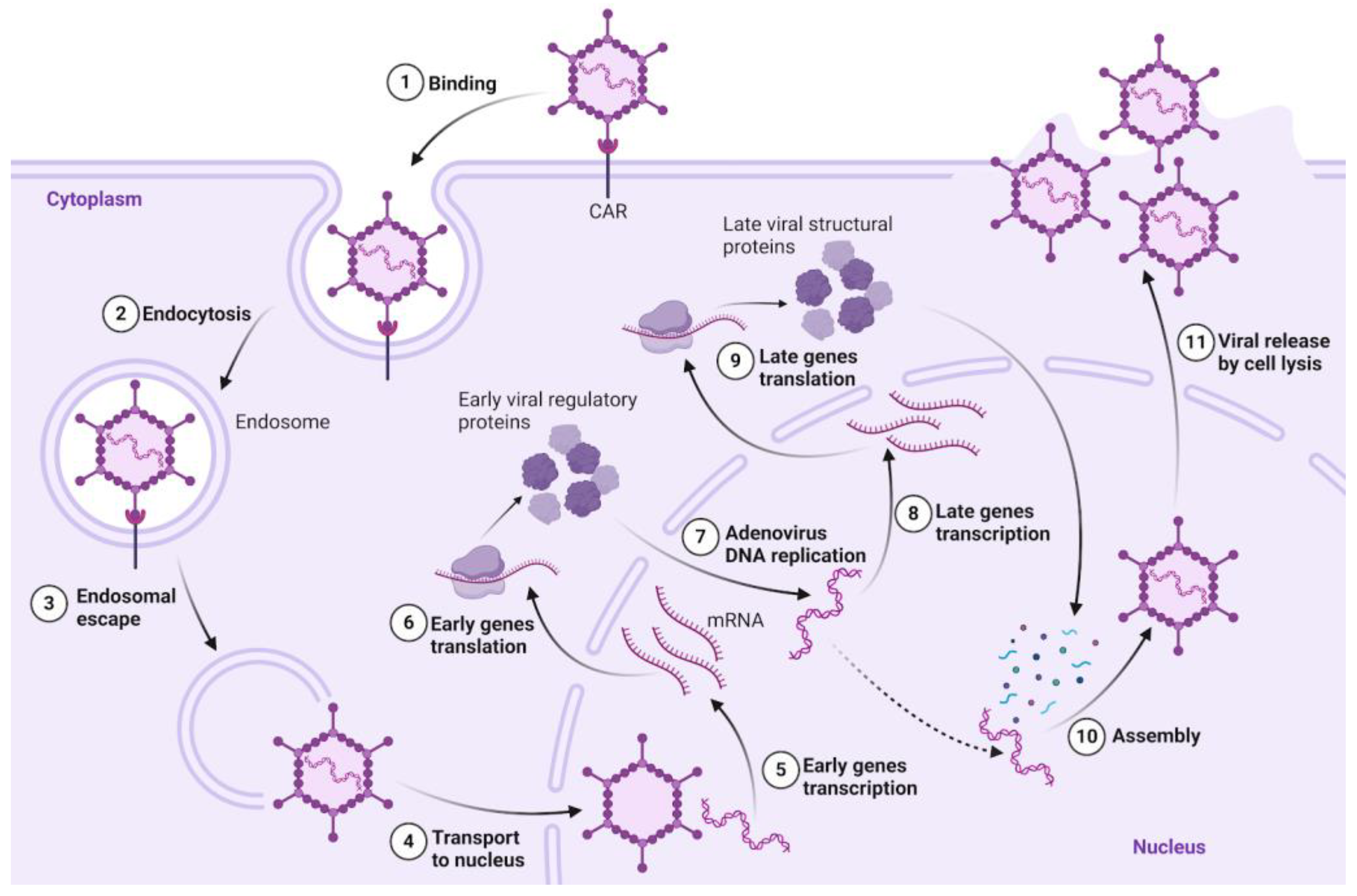

1. Introduction

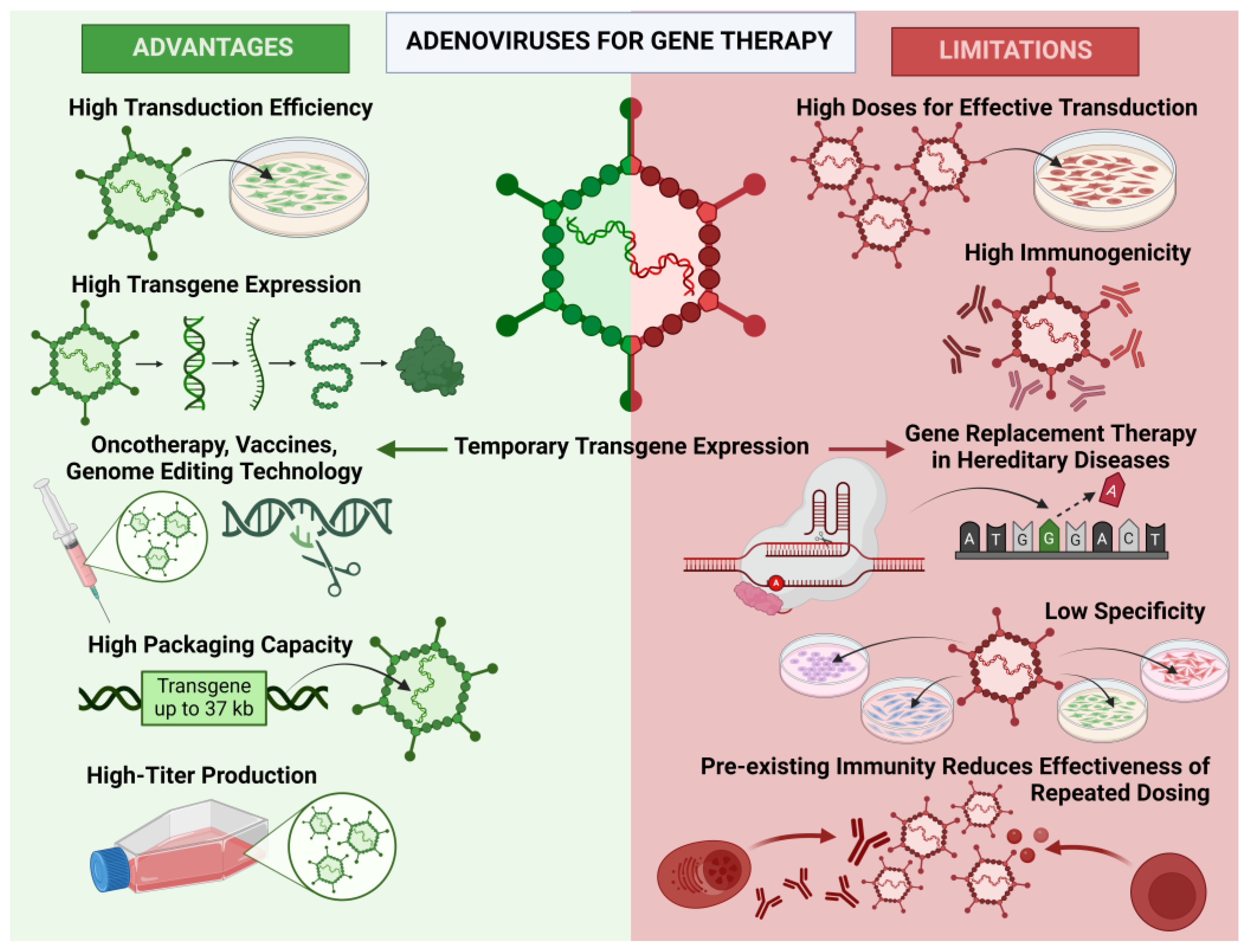

2. Adenoviral Vectors for Gene Therapy

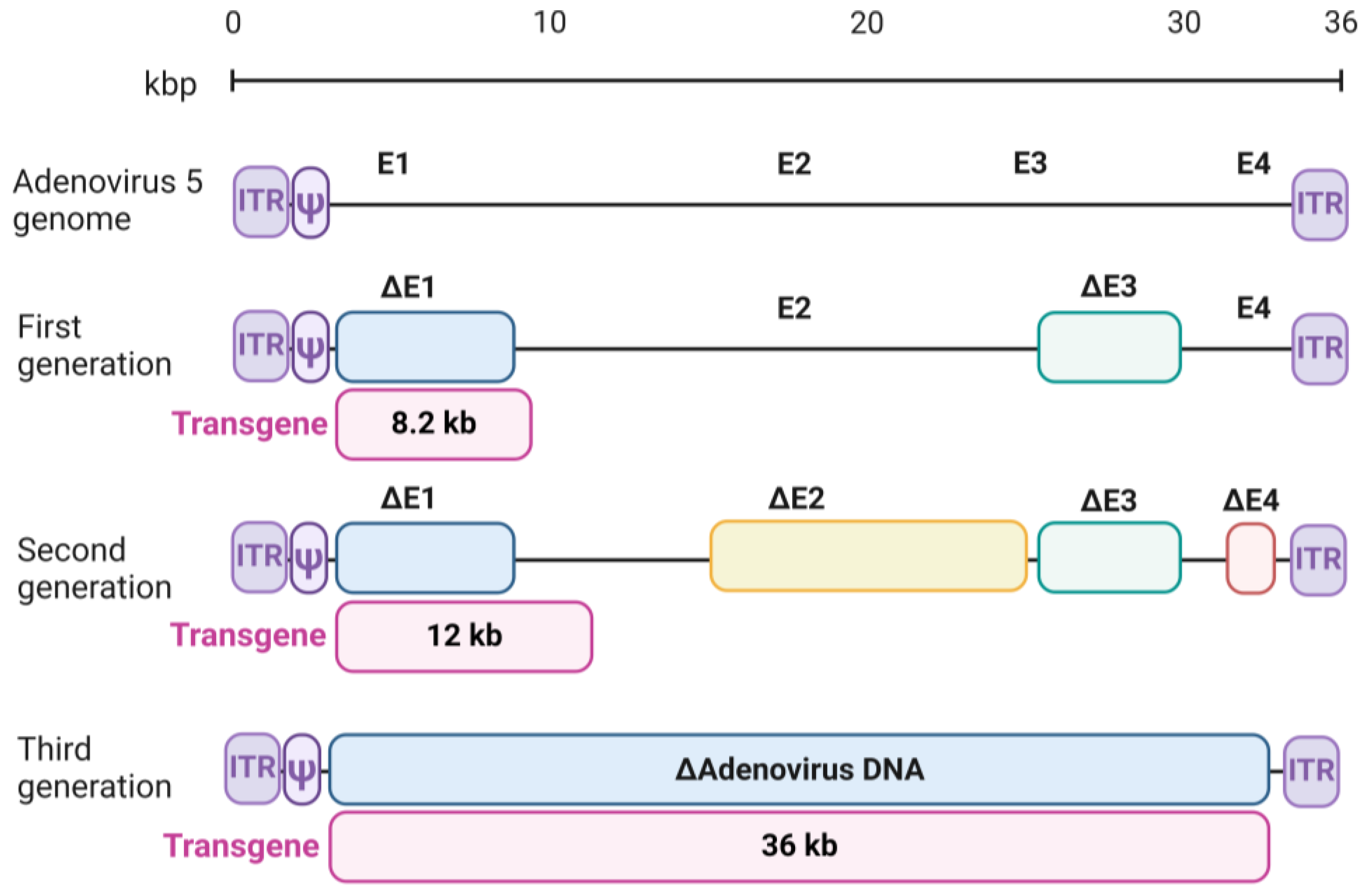

3. Evolution of Adenoviral Vectors for Gene Therapy

4. Clinical Trials Based on Adenoviral Vectors for Treating Hereditary Diseases

4.1. Gene Therapy for Cystic Fibrosis

4.2. Gene Therapy for Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency

5. Enhancing Adenoviral Vectors for Gene Therapy of Hereditary Diseases

5.1. Regulating Transgene Expression

5.2. Capsid Alterations for Targeted Tropism Control

5.3. Overcoming Immune Barriers

5.4. Mucolytics for Breaking Airway Mucus Barriers

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shenk, T.; Flint, J. Transcriptional and Transforming Activities of the Adenovirus E1A Proteins. Adv. Cancer Res. 1991, 57, 47–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, S.; Thimmapaya, B. Regulation of Adenovirus E2 Transcription Unit. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1995, 199, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, M.S. Function of Adenovirus E3 Proteins and Their Interactions with Immunoregulatory Cell Proteins. J. Gene Med. 2004, 6 (Suppl. 1), S172–S183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitzman, M.D. Functions of the Adenovirus E4 Proteins and Their Impact on Viral Vectors. Front. Biosci. 2005, 10, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, M.G.; Hayden, R.T. Adenovirus. In Diagnostic Microbiology of the Immunocompromised Host; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HAdV Working Group. Available online: http://hadvwg.gmu.edu/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Davison, A.J.; Benko, M.; Harrach, B. Genetic Content and Evolution of Adenoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 2895–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, A. ChAdOx1 NCoV-19 Vaccine for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet 2020, 396, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelvink, P.W.; Lizonova, A.; Lee, J.G.M.; Li, Y.; Bergelson, J.M.; Finberg, R.W.; Brough, D.E.; Kovesdi, I.; Wickham, T.J. The Coxsackievirus-Adenovirus Receptor Protein Can Function as a Cellular Attachment Protein for Adenovirus Serotypes from Subgroups A, C, D, E, and F. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 7909–7915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, R.W. Adenoviruses: The Nature of the Virion and of Controlling Factors in Productive or Abortive Infection and Tumorigenesis. Adv. Virus Res. 1969, 14, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, P.; González, R.A. Adenoviruses. Encycl. Infect. Immun. 2022, 2, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayedahmed, E.E.; Kumari, R.; Mittal, S.K. Current Use of Adenovirus Vectors and Their Production Methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1937, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkenhagen, L.K.; Fieldhouse, J.K.; Seto, D.; Gray, G.C. Are Adenoviruses Zoonotic? A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuguchi, H.; Hayakawa, T. Adenovirus Vectors Containing Chimeric Type 5 and Type 35 Fiber Proteins Exhibit Altered and Expanded Tropism and Increase the Size Limit of Foreign Genes. Gene 2002, 285, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havenga, M.J.E.; Lemckert, A.A.C.; Ophorst, O.J.A.E.; van Meijer, M.; Germeraad, W.T.V.; Grimbergen, J.; van den Doel, M.A.; Vogels, R.; van Deutekom, J.; Janson, A.A.M.; et al. Exploiting the Natural Diversity in Adenovirus Tropism for Therapy and Prevention of Disease. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 4612–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginn, S.L.; Amaya, A.K.; Alexander, I.E.; Edelstein, M.; Abedi, M.R. Gene Therapy Clinical Trials Worldwide to 2017: An Update. J. Gene Med. 2018, 20, e3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergelson, J.M.; Cunningham, J.A.; Droguett, G.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Krithivas, A.; Hong, J.S.; Horwitz, M.S.; Crowell, R.L.; Finberg, R.W. Isolation of a Common Receptor for Coxsackie B Viruses and Adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 1997, 275, 1320–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harui, A.; Suzuki, S.; Kochanek, S.; Mitani, K. Frequency and Stability of Chromosomal Integration of Adenovirus Vectors. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 6141–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyer, B.; Jiang, W.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, L.; Paul, R.; Feng, T.; He, T.-C. Adenoviral Vector-Mediated Gene Transfer for Human Gene Therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2001, 1, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Sainz, I.; Medina, G.N.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Koster, M.J.; Grubman, M.J.; de los Santos, T. Adenovirus-Vectored Foot-and-Mouth Disease Vaccine Confers Early and Full Protection against FMDV O1 Manisa in Swine. Virology 2017, 502, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roessler, B.J.; Allen, E.D.; Wilson, J.M.; Hartman, J.W.; Davidson, B.L. Adenoviral-Mediated Gene Transfer to Rabbit Synovium in Vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 92, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, Y.; Frisancho, J.C.; Roessler, B.J. Adenoviral-Mediated Gene Transfer into Guinea Pig Cochlear Cells in Vivo. Neurosci. Lett. 1996, 207, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.M.C.; Lochmüller, H.; O’Hara, A.; Fletcher, S.; Kakulas, B.A.; Massie, B.; Nalbantoglu, J.; Karpati, G. High-Level Dystrophin Expression after Adenovirus-Mediated Dystrophin Minigene Transfer to Skeletal Muscle of Dystrophic Dogs: Prolongation of Expression with Immunosuppression. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998, 9, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shears, L.L.; Kibbe, M.R.; Murdock, A.D.; Billiar, T.R.; Lizonova, A.; Kovesdi, I.; Watkins, S.C.; Tzeng, E. Efficient Inhibition of Intimal Hyperplasia by Adenovirus-Mediated Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Gene Transfer to Rats and Pigs in Vivo. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1998, 187, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, S.A.; Lorincz, R.; Boucher, P.; Curiel, D.T. Adenoviral Vector Vaccine Platforms in the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. npj Vaccines 2021, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumida, S.M.; Truitt, D.M.; Kishko, M.G.; Arthur, J.C.; Jackson, S.S.; Gorgone, D.A.; Lifton, M.A.; Koudstaal, W.; Pau, M.G.; Kostense, S.; et al. Neutralizing Antibodies and CD8 + T Lymphocytes Both Contribute to Immunity to Adenovirus Serotype 5 Vaccine Vectors. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2666–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flotte, T.R. Size Does Matter: Overcoming the Adeno-Associated Virus Packaging Limit. Respir. Res. 2000, 1, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, B.; Khan, N.; Arumugam, S.; Saxena, H.; Kumar, M.; Manimaran, P.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Jayandharan, G.R. Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors in Gene Therapy. In Gene and Cell Therapy: Biology and Applications; Jayandharan, G.R., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 29–56. ISBN 978-981-13-0481-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kochergin-Nikitsky, K.; Belova, L.; Lavrov, A.; Smirnikhina, S. Tissue and Cell-Type-Specific Transduction Using RAAV Vectors in Lung Diseases. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 99, 1057–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Vasan, L.; Kartono, B.; Clifford, K.; Attarpour, A.; Sharma, R.; Mandrozos, M.; Kim, A.; Zhao, W.; Belotserkovsky, A.; et al. Advances in Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, A.J.; Haddara, W.; Prevec, L.; Graham, F.L. An Efficient and Flexible System for Construction of Adenovirus Vectors with Insertions or Deletions in Early Regions 1 and 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 8802–8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, N.; Evelegh, C.; Graham, F.L. Cloning and Sequencing of the Cellular-Viral Junctions from the Human Adenovirus Type 5 Transformed 293 Cell Line. Virology 1997, 233, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duigou, G.J.; Young, C.S.H. Replication-Competent Adenovirus Formation in 293 Cells: The Recombination-Based Rate Is Influenced by Structure and Location of the Transgene Cassette and Not Increased by Overproduction of HsRad51, Rad51-Interacting, or E2F Family Proteins. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 5437–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalfitano, A.; Hauser, M.A.; Hu, H.; Serra, D.; Begy, C.R.; Chamberlain, J.S. Production and Characterization of Improved Adenovirus Vectors with the E1, E2b, and E3 Genes Deleted. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, S.; Barry, M. Current Advances and Future Challenges in Adenoviral Vector Biology and Targeting. Curr. Gene Ther. 2007, 7, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.C.; Zhou, S.; Da Costa, L.T.; Yu, J.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. A Simplified System for Generating Recombinant Adenoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2509–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochanek, S.; Schiedner, G.; Volpers, C. High-Capacity “gutless” Adenoviral Vectors. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2001, 3, 454–463. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Y.F.; Sandberg, L.; Papareddy, P.; Silver, J.; Bergh, A. Replication-Competent Ad11p Vector (RCAd11p) Efficiently Transduces and Replicates in Hormone-Refractory Metastatic Prostate Cancer Cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2009, 20, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Bishop, E.S.; Zhang, R.; Yu, X.; Farina, E.M.; Yan, S.; Zhao, C.; Zeng, Z.; Shu, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Delivery: Potential Applications for Gene and Cell-Based Therapies in the New Era of Personalized Medicine. Genes Dis. 2017, 4, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Samulski, R.J. Engineering Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors for Gene Therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, J.; Stanek, L.; Lukason, M.; Barry, E.; Russell, S.; Morris, J.; Mastis, B.; Alves, A.; Bu, J.; Shihabuddin, L.S.; et al. 301. AAV Capsid Engineering to Improve Transduction in Retina and Brain. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, S120–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashev, A.N.; Ivanova, O.E.; Eremeeva, T.P.; Iggo, R.D. Evidence of Frequent Recombination among Human Adenoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.R.; Suzuki, M. Immunology of Adenoviral Vectors in Cancer Therapy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 15, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, V.; Pesonen, S.; Diaconu, I.; Escutenaire, S.; Arstila, P.T.; Ugolini, M.; Nokisalmi, P.; Raki, M.; Laasonen, L.; Särkioja, M.; et al. Oncolytic Adenovirus Coding for Granulocyte Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor Induces Antitumoral Immunity in Cancer Patients. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 4297–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, F.; Tachibana, M.; Mizuguchi, H. Adenovirus Vector-Based Vaccine for Infectious Diseases. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2022, 42, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavda, V.P.; Bezbaruah, R.; Valu, D.; Patel, B.; Kumar, A.; Prasad, S.; Kakoti, B.B.; Kaushik, A.; Jesawadawala, M. Adenoviral Vector-Based Vaccine Platform for COVID-19: Current Status. Vaccines 2023, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Viral Vector-Based Gene Therapies in the Clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2021, 7, e10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, J.R.; Rommens, J.M.; Kerem, B.S.; Alon, N.O.A.; Rozmahel, R.; Grzelczak, Z.; Zielenski, J.; Lok, S.I.; Plavsic, N.; Chou, J.L.; et al. Identification of the Cystic Fibrosis Gene: Cloning and Characterization of Complementary DNA. Science 1989, 245, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, M.J.; Smith, A.E. Molecular Mechanisms of CFTR Chloride Channel Dysfunction in Cystic Fibrosis. Cell 1993, 73, 1251–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, J.B.; Robinson, C.B.; McCoy, K.S.; Shell, R.; Sferra, T.J.; Chirmule, N.; Magosin, S.A.; Propert, K.J.; Brown-Parr, E.C.; Hughes, J.V.; et al. A Phase I Study of Adenovirus-Mediated Transfer of the Human Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Gene to a Lung Segment of Individuals with Cystic Fibrosis. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 2973–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.R.; Hohneker, K.W.; Zhou, Z.; Olsen, J.C.; Noah, T.L.; Hu, P.-C.; Leigh, M.W.; Engelhardt, J.F.; Edwards, L.J.; Jones, K.R.; et al. A Controlled Study of Adenoviral-Vector-Mediated Gene Transfer in the Nasal Epithelium of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.G.; Boyles, S.E.; Wilson, J.; Boucher, R.C. Normalization of Raised Sodium Absorption and Raised Calcium-Mediated Chloride Secretion by Adenovirus-Mediated Expression of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator in Primary Human Cystic Fibrosis Airway Epithelial Cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 95, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.L.; Metzger, M.; Danel, C.; Rosenfeld, M.A.; Crystal, R.G. Acute Responses of Non-Human Primates to Airway Delivery of an Adenovirus Vector Containing the Human Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator CDNA. Hum. Gene Ther. 1994, 5, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, B.G.; Leopold, P.L.; Hackett, N.R.; Grasso, T.M.; Williams, P.M.; Tucker, A.L.; Kaner, R.J.; Ferris, B.; Gonda, I.; Sweeney, T.D.; et al. Airway Epithelial CFTR MRNA Expression in Cystic Fibrosis Patients after Repetitive Administration of a Recombinant Adenovirus. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 104, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cone, R.A. Barrier Properties of Mucus. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.K.; Wang, Y.Y.; Hanes, J. Mucus-Penetrating Nanoparticles for Drug and Gene Delivery to Mucosal Tissues. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakland, M.; Sinn, P.L.; McCray, P.B. Advances in Cell and Gene-Based Therapies for Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, N.; Rudolph, C.; Braeckmans, K.; De Smedt, S.C.; Demeester, J. Extracellular Barriers in Respiratory Gene Therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickles, R.J.; McCarty, D.; Matsui, H.; Hart, P.J.; Randell, S.H.; Boucher, R.C. Limited Entry of Adenovirus Vectors into Well-Differentiated Airway Epithelium Is Responsible for Inefficient Gene Transfer. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 6014–6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltimore, R.S.; Christie, C.D.C.; Walker Smith, G.J. Immunohistopathologic Localization of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Lungs from Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Implications for the Pathogenesis of Progressive Lung Deterioration. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1989, 140, 1650–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worlitzsch, D.; Tarran, R.; Ulrich, M.; Schwab, U.; Cekici, A.; Meyer, K.C.; Birrer, P.; Bellon, G.; Berger, J.; Weiss, T.; et al. Effects of Reduced Mucus Oxygen Concentration in Airway Pseudomonas Infections of Cystic Fibrosis Patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, J.S.; Lai, S.K.; Wang, Y.Y.; Ensign, L.M.; Zeitlin, P.L.; Boyle, M.P.; Hanes, J. The Penetration of Fresh Undiluted Sputum Expectorated by Cystic Fibrosis Patients by Non-Adhesive Polymer Nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2591–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheils, C.A.; Käs, J.; Travassos, W.; Allen, P.G.; Janmey, P.A.; Wohl, M.E.; Stossel, T.P. Actin Filaments Mediate DNA Fiber Formation in Chronic Inflammatory Airway Disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1996, 148, 919–927. [Google Scholar]

- Lethem, M.I.; James, S.L.; Marriott, C.; Burke, J.F. The Origin of DNA Associated with Mucus Glycoproteins in Cystic Fibrosis Sputum. Eur. Respir. J. 1990, 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, R.W.; Grunst, T.; Bergelson, J.M.; Finberg, R.W.; Welsh, M.J.; Zabner, J. Basolateral Localization of Fiber Receptors Limits Adenovirus Infection from the Apical Surface of Airway Epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 10219–10226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickles, R.J.; Fahrner, J.A.; Petrella, J.M.; Boucher, R.C.; Bergelson, J.M. Retargeting the Coxsackievirus and Adenovirus Receptor to the Apical Surface of Polarized Epithelial Cells Reveals the Glycocalyx as a Barrier to Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Transfer. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6050–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, J.R.; Randell, S.H.; Hogan, B.L.M. Airway Basal Stem Cells: A Perspective on Their Roles in Epithelial Homeostasis and Remodeling. Dis. Model. Mech. 2010, 3, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raper, S.E.; Magosin, S.; Simoes, H.; Speicher, L.; Hughes, J.; Tazelaar, J.; Wivel, N.A.; Wilson, J.M.; Batshaw, M.L.; Yudkoff, M.; et al. A Pilot Study of in Vivo Liver-Directed Gene Transfer with an Adenoviral Vector in Partial Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency. Hum. Gene Ther. 2002, 13, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Robinson, M.B.; Batshaw, M.L.; Furth, E.E.; Smith, I.; Wilson, J.M. Prolonged Metabolic Correction in Adult Ornithine Transcarbamylase-Deficient Mice with Adenoviral Vectors. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 3639–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, S.E.; Haskal, Z.J.; Ye, X.; Pugh, C.; Furth, E.E.; Gao, G.P.; Wilson, J.M. Selective Gene Transfer into the Liver of Non-Human Primates with E1-Deleted, E2A-Defective, or E1-E4 Deleted Recombinant Adenoviruses. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998, 9, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, S.E.; Chirmule, N.; Lee, F.S.; Wivel, N.A.; Bagg, A.; Gao, G.P.; Wilson, J.M.; Batshaw, M.L. Fatal Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome in a Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficient Patient Following Adenoviral Gene Transfer. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2003, 80, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechner, H.; Haack, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Eizema, K.; Pauschinger, M.; Schoemaker, R.G.; Van Veghel, R.; Houtsmuller, A.B.; Schultheiss, H.P.; et al. Expression of Coxsackie Adenovirus Receptor and Alphav-Integrin Does Not Correlate with Adenovector Targeting in Vivo Indicating Anatomical Vector Barriers. Gene Ther. 1999, 6, 1520–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzani, M.; Annunziato, S.; Adams, D.J.; Montini, E. Cancer Gene Discovery: Exploiting Insertional Mutagenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulos, T.; Munye, M.M.; Yáñez-Muñoz, R.J. Nonintegrating Gene Therapy Vectors. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 31, 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imler, J.L.; Dupuit, F.; Chartier, C.; Accart, N.; Dieterle, A.; Schultz, H.; Puchelle, E.; Pavirani, A. Targeting Cell-Specific Gene Expression with an Adenovirus Vector Containing the LacZ Gene under the Control of the CFTR Promoter. Gene Ther. 1996, 3, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Toietta, G.; Koehler, D.R.; Finegold, M.J.; Lee, B.; Hu, J.; Beaudet, A.L. Reduced Inflammation and Improved Airway Expression Using Helper-Dependent Adenoviral Vectors with a K18 Promoter. Mol. Ther. 2003, 7, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, L.; Morral, N.; Zhou, H.; Garcia, R.; Parks, R.J.; Kochanek, S.; Graham, F.L.; Lee, B.; Beaudet, A.L. Use of a Liver-Specific Promoter Reduces Immune Response to the Transgene in Adenoviral Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 1773–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granio, O.; Excoffon, K.J.D.A.; Henning, P.; Melin, P.; Norez, C.; Gonzalez, G.; Karp, P.H.; Magnusson, M.K.; Habib, N.; Lindholm, L.; et al. Adenovirus 5-Fiber 35 Chimeric Vector Mediates Efficient Apical Correction of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Defect in Cystic Fibrosis Primary Airway Epithelia. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 21, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabner, J.; Chillon, M.; Grunst, T.; Moninger, T.O.; Davidson, B.L.; Gregory, R.; Armentano, D. A Chimeric Type 2 Adenovirus Vector with a Type 17 Fiber Enhances Gene Transfer to Human Airway Epithelia. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 8689–8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.T.; Miller, C.R.; Kim, M.; Dmitriev, I.; Mikheeva, G.; Krasnykh, V.; Curiel, D.T. A System for the Propagation of Adenoviral Vectors with Genetically Modified Receptor Specificities. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drapkin, P.T.; O’Riordan, C.R.; Yi, S.M.; Chiorini, J.A.; Cardella, J.; Zabner, J.; Welsh, M.J. Targeting the Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor Enhances Gene Transfer to Human Airway Epithelia. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 105, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidaka, C.; Milano, E.; Leopold, P.L.; Bergelson, J.M.; Hackett, N.R.; Finberg, R.W.; Wickham, T.J.; Kovesdi, I.; Roelvink, P.; Crystal, R.G. CAR-Dependent and CAR-Independent Pathways of Adenovirus Vector-Mediated Gene Transfer and Expression in Human Fibroblasts. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.E.; Edwards, P.; Wickham, T.J.; Castro, M.G.; Lowenstein, P.R. Adenovirus Binding to the Coxsackievirus and Adenovirus Receptor or Integrins Is Not Required to Elicit Brain Inflammation but Is Necessary to Transduce Specific Neural Cell Types. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3452–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis Jeune, V.; Joergensen, J.A.; Hajjar, R.J.; Weber, T. Pre-Existing Anti-Adeno-Associated Virus Antibodies as a Challenge in AAV Gene Therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2013, 24, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Heller, G.J.; Barry, M.E.; Crosby, C.M.; Turner, M.A.; Barry, M.A. Evaluation of Polymer Shielding for Adenovirus Serotype 6 (Ad6) for Systemic Virotherapy against Human Prostate Cancers. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2016, 3, 15021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shantha Kumar, T.; Soppimath, K.; Nachaegari, S. Novel Delivery Technologies for Protein and Peptide Therapeutics. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2006, 7, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, S.; Sahoo, S.K. Nanomedicine: Clinical Applications of Polyethylene Glycol Conjugated Proteins and Drugs. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2006, 45, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croyle, M.A.; Chirmule, N.; Zhang, Y.; Wilson, J.M. “Stealth” Adenoviruses Blunt Cell-Mediated and Humoral Immune Responses against the Virus and Allow for Significant Gene Expression upon Readministration in the Lung. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 4792–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, C.R.; Lachapelle, A.; Delgado, C.; Parkes, V.; Wadsworth, S.C.; Smith, A.E.; Francis, G.E. PEGylation of Adenovirus with Retention of Infectivity and Protection from Neutralizing Antibody in Vitro and in Vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, R.A.; Chen, Z.R.; Hu, J. Potential of Helper-Dependent Adenoviral Vectors in CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Lung Gene Therapy. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Duan, R.; Hu, J. Overcoming Immunological Challenges to Helper-Dependent Adenoviral Vector-Mediated Long-Term CFTR Expression in Mouse Airways. Genes 2020, 11, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, D.R.; Frndova, H.; Leung, K.; Louca, E.; Palmer, D.; Ng, P.; McKerlie, C.; Cox, P.; Coates, A.L.; Hu, J. Aerosol Delivery of an Enhanced Helper-Dependent Adenovirus Formulation to Rabbit Lung Using an Intratracheal Catheter. J. Gene Med. 2005, 7, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.; St. George, J.A.; Lukason, M.; Cheng, S.H.; Scheule, R.K.; Eastman, S.J. EGTA Enhancement of Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Transfer to Mouse Tracheal Epithelium in Vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001, 12, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.W.; Grubb, B.R.; Johnson, L.G.; Boucher, R.C. Enhanced in Vivo Airway Gene Transfer via Transient Modification of Host Barrier Properties with a Surface-Active Agent. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998, 9, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.G.; Vanhook, M.K.; Coyne, C.B.; Haykal-Coates, N.; Gavett, S.H. Safety and Efficiency of Modulating Paracellular Permeability to Enhance Airway Epithelial Gene Transfer In Vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 2003, 14, 729–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zabner, J.; Deering, C.; Launspach, J.; Shao, J.; Bodner, M.; Jolly, D.J.; Davidson, B.L.; Mccray, P.B. Increasing Epithelial Junction Permeability Enhances Gene Transfer to Airway Epithelia In Vivo. Rapid Commun. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000, 22, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Zabner, J.; Welsh, M.J. Delivery of an Adenovirus Vector in a Calcium Phosphate Coprecipitate Enhances the Therapeutic Index of Gene Transfer to Airway Epithelia. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.M.; Pennington, S.E.; St. George, J.A.; Woodworth, L.A.; Fasbender, A.; Marshall, J.; Cheng, S.H.; Wadsworth, S.C.; Gregory, R.J.; Smith, A.E. Potentiation of Gene Transfer to the Mouse Lung by Complexes of Adenovirus Vector and Polycations Improves Therapeutic Potential. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998, 9, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NCT Number | Study Title | Study Status | Vector | Phase | Enrollment | Study Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cystic Fibrosis | ||||||

| NCT00004779 | Phase I Pilot Study of Ad5-CB-CFTR, an Adenovirus Vector Containing the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Gene, in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis | Completed | Ad5-CB-CFTR | Phase 1 | 12 | 1993–1995 |

| NCT00004287 | Phase I Study of the Third Generation Adenovirus H5.001CBCFTR in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis | Completed | H5.001CBCFTR | Phase 1 | 11 | 1999 |

| Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency (OTCD) | ||||||

| NCT00004307 | Study of Treatment and Metabolism in Patients with Urea Cycle Disorders | Unknown | AdV-OTC | Phase 1 | 66 | 1999 |

| NCT00004386 | Phase I Pilot Study of Liver-Directed Gene Therapy for Partial Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency | Terminated | AdV-OTC | Phase 1 | 18 | 1999 |

| NCT00004498 | Phase I Study of Adenoviral Vector Mediated Gene Transfer for Ornithine Transcarbamylase in Adults with Partial Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency | Terminated | AdV-OTC | Phase 1 | 18 | 1999 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muravyeva, A.; Smirnikhina, S. Adenoviral Vectors for Gene Therapy of Hereditary Diseases. Biology 2024, 13, 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13121052

Muravyeva A, Smirnikhina S. Adenoviral Vectors for Gene Therapy of Hereditary Diseases. Biology. 2024; 13(12):1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13121052

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuravyeva, Anna, and Svetlana Smirnikhina. 2024. "Adenoviral Vectors for Gene Therapy of Hereditary Diseases" Biology 13, no. 12: 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13121052

APA StyleMuravyeva, A., & Smirnikhina, S. (2024). Adenoviral Vectors for Gene Therapy of Hereditary Diseases. Biology, 13(12), 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13121052