Abstract

Thick thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) are the main choice in the aviation industry due to their ability to handle elevated temperature exposure in turbines. However, the efficacy of thick TBCs has not been adequate. This study presents a highly durable, thick top-coat (TC) of Lanthanum–gadolinium–yttria stabilized zirconia (La–Gd–YSZ) on high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF)-bond coat (HVOF-BC). Crack propagation was quantitatively assessed using a three-dimensional (3D) measuring laser microscope due to higher reliability in calculating the actual crack length of TBC. The findings revealed the HVOF-BC is highly durable with intact structural composition, while the conventional TBC of atmospheric plasma spraying (APS) bond coat (APS-BC) of the same composition and thickness with identical TC was detached at a crack-susceptible zone. The significant enhancement in HVOF-BC is due to the low mixed-oxides growth rate in thermally grown oxide (TGO) with a uniform and dense protective layer of stable Al2O3 which reduces crack propagation. Meanwhile, the failure in APS-BC can be attributed to the high TGO growth rate and thickness with segmented and unstable Al2O3. Furthermore, detrimental mixed oxides such as spinel Ni(Cr,Al)2O4 and NiO lead to disastrous horizontal and compressive cracks. To that end, we study the effect of TGO growth and crack propagation on HVOF-BC TBCs using APS-BC TBCs as a reference.

1. Introduction

Thermally sprayed coatings are often used to protect metallic components that suffer breakdown from wear, corrosion or excessive heat load during service in thermally drastic environments [1]. These coatings are widely used as a thermal barrier coating (TBC) applied on gas turbines and also in the aeronautical and automotive industries [2]. Performance of gas turbines is enhanced significantly by reducing the cooling or increasing the gas temperature during service. Hence, a thick protection layer of top-coat (TC) for TBC is able to drop the temperature by up to 170 °C in a gas turbine system [3]. The low-thermal conductivity in TBC causes low heat transfer from TC and achieves effective cooling and reduces the surface temperature. A thickness of above 0.25 mm is considered as thick TC [4].

However, there is a trade-off between low substrate distress and high TBC distress [4]. Thick TC promotes low substrate temperature on a big scale and prolongs substrate life. At the same time, thicker TC may increase surface temperature during operation and exceeds the ceramic materials limit at elevated temperatures [5], owing to the excessive growth of thermally grown oxide (TGO) at the interface of the TC/bond coat and leading to detached TC from the bond coat (BC) [6]. In addition to that, conventional, partially yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ) TC has limited phase stability, reducing the high-temperature capability leading to TBC early failure [7]. Therefore, TC and BC are identified as important constituents in developing an effective TBC.

These shortcomings have initiated plenty of research on alternate ceramics to YSZ [7,8]. In particular, doping with rare earth zirconates in TC was found to control porosity and improve the microstructure [7,9]. Lanthanum (La) is a rare earth material which has been introduced as dopant in the TC shows a stable phase up to its melting temperature of 2295 ± 10 °C [10]. Mauer et al. reported that La2O3∙ZrO2 is best processed by atmospheric plasma spraying (APS) at a low power, where it exhibited high durability due to the high fusion enthalpy of ~350 kJ mol−1 of La2O3 [10]. Composition of La and gadolinium (Gd) shows great promise for TBC materials with low thermal conductivity, low sintering rate and high thermal stability reaching around the melting point (2300 °C) [11]. Besides that, rare earth phosphates such as LaPO4 in TC reported by Zhang et al. are highly resistant to corrosion and possessed only a little detrimental effect on the coating microstructure [12].

BC is the most vital constituent in TBC as it strengthens the adhesion of the TC to the substrate and acts as an oxidation and corrosion barrier to the superalloy. At elevated temperatures, oxygen diffusion from TC towards BC through micro-cracks inside the TC oxidizes the BC and forms an oxidized scale known as TGO [13,14,15]. TGO plays an important role in spallation and the lifetime of TBC. It acts as a diffusion barrier to suppress the growth of other detrimental oxides during further oxidation in service if a continuous scale of Al2O3 is formed on the BC. However, if an inconsistent layer of TGO was grown on the BC, a cluster of oxides such as chromia ((Cr,Al)2O3), spinel (Ni(Cr,Al)2O4) and nickel oxide (NiO) may grow along with it, leading to TBC failure. This is due to the separation of the ceramic TC from the substrate [16,17,18]. The deposition method of MCrAlY on the BC is outlined as the main reason behind the TBC failure.

MCrAlY coatings are typically deposited by electron beam physical vapor deposition, air plasma spray (APS) and high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) [19,20,21]. Li et al. stated that the durability of TBC can be improved by changing the microstructure in the BC [22]. Greater thickness in TGO of the traditional APS-BC was observed due to the presence of mixed oxides such as chromia, spinel and nickel oxide. The results revealed that these mixed oxides deteriorate the durability of TBCs. They also mentioned that the critical thickness of TGO corresponding to the change of failure mode is around 5–6 µm [22]. Moreover, strength difference (compression and tension) in TBC was studied in the previous literature [23]. The strength difference property was defined as the significant difference between compressions and tensile strengths. They mentioned that TGO thickening generates compressive growth stress and weakens the out-of-plane displacement of the TGO layer [23]. Meanwhile, the tensile stress was distributed at the TC valley and BC peak regions, which is near the interface defects [23].

However, despite the HVOF technique being costly, it has high adherence and corrosion resistance with a continuous growth of the Al2O3 layer [24]. Thus, HVOF coating is dense, adherent and contains less oxide with fewer voids and considerably reduces the penetration of oxygen into the TBC from the existing micro-cracks at elevated temperatures. That the BC deposition technique has a strong influence in producing an efficient TBC system is speculated.

Moreover, Nafsin et al. have studied the stability of Lanthanum–gadolinium–yttria stabilized zirconia (La–Gd–YSZ) complex coating [25]. They found further increases in thermal stability, with retaining the sphere shape and nanoscale crystallite size up to 1000 °C for at least 3 h, while at 1100 °C the spheres started necking but the spheres were still in shape [25]. In this work, we used higher temperatures of 1200 and 1300 °C for the isothermal oxidation test on La–Gd–YSZ (Y-5 wt.%, Zr-65 wt.% and a little amount of other rare earth elements; La-0.15 wt.% and Gd-0.1 wt.%) coating. This coating is expected to increase thermal stability and reduce the formation cracks in the coating, hypothetically allowing robust resistance to spallation even at extremely high temperatures in TBCs by taking into account the method used for preparing the BC. To understand the effect of crack propagation in the coating, two different spraying methods for BC, APS and HVOF were selected and used under different temperatures. The present work demonstrates the feasibility of depositing highly durable HVOF-BC and compares it with the conventional APS-BC on thick TBC. The identical thick TC is added with rare earth elements such as La and Gd. Thus, the influence of TGO growth with mixed oxides and crack propagation on HVOF-BC incorporating APS-BC as a reference in thick La–Gd–YSZ TBCs is studied.

2. Experimental Procedure

The samples were prepared by applying different deposition techniques for bond coats, whereas an identical deposition technique was used for top-coats in each case. The ceramic TC consists of Y-5 wt.%, Zr-65 wt.% and a little amount of other rare earth elements; La-0.15 wt.% and Gd-0.1 wt.% and is deposited via APS technique (Flame Spray Technologies B.V., Duiven, The Netherlands). The parameters used in TC deposition using the APS method is shown in Table 1. The BC consists of Ni–Cr–Al–Y elements produced by using APS and HVOF spraying systems (Flame Spray Technologies B.V., Duiven, The Netherlands). The coatings were deposited on a Ni base superalloy, Nimonic 263 (Nim263). Both APS and HVOF used MP-100 with robot manioulation of 6-axes ABB IRB2400/16. The gun used for APS technique is F4-MB Plasma Gun with 6 mm nozzle diameter. Meanwhile, HVOF technique used JP5000 Liquid Fuel Gun.

Table 1.

Parameters used for depositing top coat (TC) (Lanthanum–gadolinium–yttria stabilized zirconia (La–Gd–YSZ)) via the atmospheric plasma spraying (APS) technique.

A thermal oxidation test was performed at 1200 and 1300 °C for 1, 10, 100 and 300 h of oxidation time with 150 °C of cooling air. These temperatures were selected to withstand higher temperatures than the normal since the TC includes rare earth-YSZ. The samples were abbreviated as C1 (1200 °C; 1 h), C2 (1200 °C; 10 h), C3 (1200 °C; 100 h), C4 (1200 °C; 300 h), C5 (1300 °C; 1 h), C6 (1300 °C; 10 h), C7 (1300 °C; 100 h) and C8 (1300 °C; 300 h) for APS-BC. Meanwhile, D1 (1200 °C; 1 h), D2 (1200 °C; 10 h), D3 (1200 °C; 100 h), D4 (1200 °C; 300 h), D5 (1300 °C; 1 h), D6 (1300 °C; 10 h), D7 (1300 °C; 100 h) and D8 (1300 °C; 300 h) for HVOF-BC. Table 2 lists the abbreviations of the TBC samples used in this work. The specimens were then furnace-cooled and removed only after cooling was completed to prevent thermal shocks. The samples with dimensions of 60 mm × 60 mm × 6 mm were cross-sectioned to 20 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm for characterizing purposes by using a manual milling machine and surface finishing process. The samples were then mounted on a mounting cup using a resin-mixture. Once the molding process was done, rough grinding and polishing took place as the final stage of sample preparation.

Table 2.

Thermal barrier coating (TBC) sample abbreviations according to temperature and oxidation hours.

Surface and cross-section of the prepared samples were characterized by using scanning electron microscope (SEM; JEOL JSM 6010 LA/LV, Kajang, Malaysia) equipped with energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS). The porosity analysis was conducted using ASTME 2109-01(201) standards [26] to determine the percentage area of porosity in the BC. The BC porosity was characterized using the percentage of pore surface content on the surface of the whole BC area (%). The BC porosity was evaluated using image-J software (version v1.52a) to threshold black areas of SEM image (pores) and the percentage area porosity was calculated automatically by image-J. The percentage area represents the percent of pores in the selected area of BC. For the mixed oxides content analysis, backscattered electron imaging mode (compo) was used to find oxide clusters at the TGO. Both the area percentage of porosity and mixed oxides content and also thickness was measured by coupling SEM and image analysis using image-J software. Al2O3 thickness ratio means the percentage of alumina thickness versus mixed oxide thickness within an entire TGO thickness.

The crack morphology evaluation was done using fractographic analysis with direct observation of the coating surface. This method is feasible for crack initiation and crack growth study. However, this method is not feasible for complex coating. Thus, a three-dimensional (3D) measuring laser microscope was used in the present work for real-time observations and measurements for complex coatings. In contrast to conventional direct observation methods, it provides a non-planar surface topography image in 3D subjected to topographic maps. 3D measuring laser microscope (Olympus LEXT OLS4100, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) was conducted to quantify crack length in the TC and BC. Differential interference contrast (DIC) was applied for improved crack morphology. The crack length was obtained according to the following equation:

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure

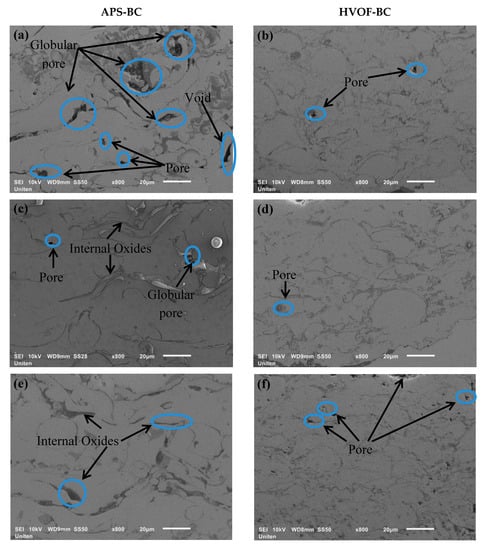

The microstructure of the APS-BC and HVOF-BC cross sections are illustrated in Figure 1. HVOF-BC exhibits a denser coating than APS-BC due to a large amount of kinetic energy provided that it propels the molten material at greater speeds, whereas APS-BC has low particle velocity. The APS-BC contained globular pores and voids which reduced at longer exposures, while HVOF-BC contained fine-scale pores. The high-speed impact by HVOF deforms and spreads the particles to form a lamellar structure.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrograph of bond coat thermally oxidized at 1200 °C for (a) APS-1 h, (b) high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF)-1 h, (c) APS-300 h and (d) HVOF-300 h, and 1300 °C for (e) APS-1 h, (f) HVOF-1 h, (g) APS-300 h and (h) HVOF-300 h.

The porosity of APS and HVOF bond coats is shown in Figure 2. The results show that the porosity of the bond coat is influenced by temperature and oxidation time. The APS BC showed higher porosity than HVOF for each temperature, which is also observed in Figure 1. The higher porosity is due to the open-air atmospheric production of APS. Meanwhile, HVOF exhibits low porosity due to the direct stream of hot gas and powder towards the surface of the substrate that is to be coated [26]. The powder is partially melted in the stream and is deposited upon the Ni-substrate. In addition to that, a favorable bond coat has lower porosity where it increases the bond strength between the ceramic TC and BC by providing good adhesion and consequently preventing it from spallation.

Figure 2.

Porosity APS and HVOF bond coats for 1200 °C and 1300 °C with various oxidation time.

However, the porosity of BC decreases as the temperature and oxidation time increases, as observed in Figure 2. The reduction in porosity is due to the process of sintering upon prolonged exposure to high temperatures [27]. As observed in Figure 1, a low cumulative pore volume fraction is formed at the exposure time of 300 h for both APS and HVOF bond coats, resulting in closure of pores and formation of internal oxides at longer oxidation time that leads to a decrease in porosity. Internal oxides are formed in the BC during oxidation caused by oxygen infiltration via the porosities and micro-cracks of the TGO layer [28]. It is to be noted that internal oxides are more prominent and thicker in APS-BC than in HVOF-BC. Moreover, the pores have been filled with internal oxides such as Al2O3 and mixed oxides at longer oxidation hours in the APS-BC, as observed in Figure 1a,g. Meanwhile, HVOF-BC exhibited a dense internal oxide, indicating a slow growth of oxide in BC due to BC oxidation.

3.2. Thermally Grown Oxide (TGO) Growth

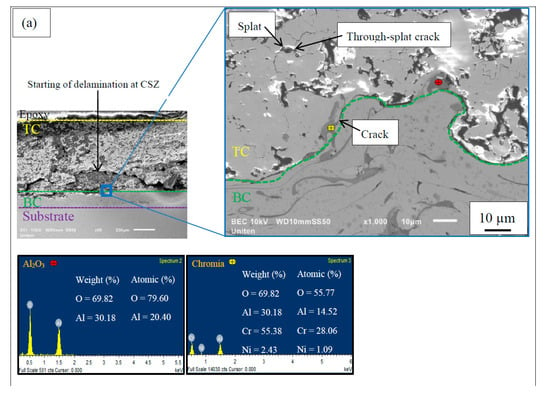

Figure 3 illustrates a TGO consisting of an oxide layer of predominantly Al2O3 formed at the interface of TC/BC along with the EDS results. The segmented TGO layer is observed at the interface for APS-BC, whereas a continuous uniform layer of dense TGO was formed for HVOF-BC. A continuous TGO layer could not be maintained after long-term thermal exposure in APS-BC due to Al depletion in the BC (formation of more mixed oxides) [29]. The continuous layer of TGO would act as a diffusion barrier to inhibit the formation of detrimental mixed oxides, thus providing protection from further oxidation and improving durability [30].

Figure 3.

SEM micrograph of the cross-sectional top-coat/bond-coat (TC/BC) interface thermally oxidized for APS-BC at (a) 1200 °C (1 h), (b) 1200 °C (300 h), (c) 1300 °C (1 h) and (d) 1300 °C (300 h), and HVOF-BC at (e) 1200 °C (1 h), (f) 1200 °C (300 h), (g) 1300 °C (1 h) and (h) 1300 °C (300 h).

Apart from Al2O3, growth of some mixed oxide clusters was also observed in the TGO layer in Figure 3. These mixed oxide clusters consist of chromia ((Cr,Al)2O3), spinel (Ni(Cr,Al)2O4) and nickel oxide (NiO) [16]. These clusters were identified according to the compositions from previous literature [31,32], where, the chromia + spinel layer consists of Ni (5–16 at.%), Al + Cr (28–43 at.%). Moreover, to differentiate (Cr,Al)2O3 and NiAl2O4 from Ni(Cr,Al)2O4, the composition of Ni is <8 at% and Al + Cr is >35 at.%, and Ni (13–16 at.%) and Al (27–30 at.%), respectively [33]. The TGO content including Al2O3 and types of mixed oxides with the presence of pores at TGO in APS and HVOF bond coats are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Thermally Grown Oxide (TGO) content, types of crack and presence of pores in APS and HVOF bond coats.

The inward diffusion of oxidants from the TC and outward diffusion of elements presented in BC (Al, Ni, Cr) leads to a reaction zone on the TC/BC interface which is known as TGO. Chromia was already formed at 1200 °C for 1 h of oxidation (C1 and D1) due to the oxygen atom from TC that easily diffuses across the TC/BC interface region and arrives at BC by the process of discrete hopping, it even arrives at the BC/substrate interface [33]. This process is accelerated with the assistance of interconnected segmented cracks and voids in the TC (Figure 3). Bengtsson et al. [33] mentioned that the segmentation crack network is usually found in thick lamellar TC. At high temperatures, the oxygen atom (O) or molecule (O2) that confront metallic phases will react to form stable oxides, on account of high affinities of oxygen with Al and Cr, and form Al2O3 and Cr2O3, as in the following equation [34]:

The high concentration of Al and Cr forms a protective layer of Al2O3 and Cr2O3 that improves high-temperature property and slow consumption of Al and Cr. Al2O3 is formed before Cr2O3 due to the Gibs free-energy of Al2O3 and Cr2O3 with −1270.5 kJ/mol and −803.0 kJ/mol, respectively [35]. This is where Al diffuses to the surface of BC and forms Al2O3. Even though it is a short oxidation time of 1 h (C5 and D5), chromia mixed with spinel was seen at 1300 °C. This is due to the high temperature that facilitates a quicker reaction between diffused Ni and Cr from BC with oxygen, owing to greater kinetic energy between the particles [36]. At this time, Ni reacted with Al2O3, Cr2O3 and O2 and formed Ni(Cr,Al)2O4, as in the following equation [34]:

After 300 h of oxidation (C4, C8, D4 and D8), the presence of Cr3+ was not observed along the TGO layer and spinel nickel aluminate (NiAl2O4) was formed as Al and Cr have been consumed continuously to below the detection threshold. At lower Cr concentration, Ni reacts with Al2O3 and O2 to produce NiAl2O4, as seen in Equation (5) [37]. Formation of spinel in APS-BC is faster than HVOF-BC where the growth of NiAl2O4 was already observed in C5, whereas D5 still contains Cr with growth of Ni(Cr,Al)2O4. This indicates slower growth rate of mixed oxide in HVOF-BC than in APS-BC.

At the same time, 300 h of exposure in the air adds the presence of the NiO in APS-BC (C4 and C8) where it was not found in HVOF-BC. This observation is due to the Al and Cr depletion, where Ni reacts with the continuous invasive oxygen to form NiO after the large growth of Al2O3, Cr2O3, Ni(Cr,Al)2O4 and NiAl2O4, as seen in the following Equation (6) [34]. Pores are observed in C4 and C8 near NiO, which points out the invasive oxygen diffusion at the TGO layer.

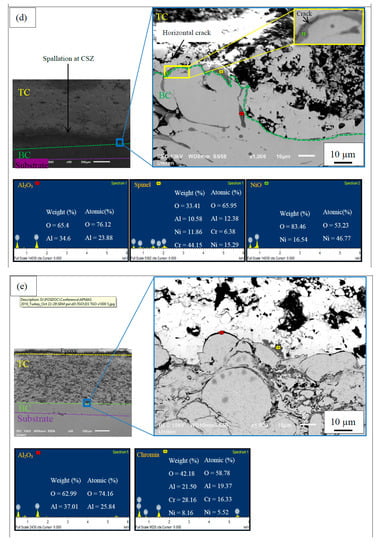

The mixed oxide thickness ratio of APS-BC and HVOF-BC are illustrated in Figure 4. APS-BC shows a greater thickness ratio of mixed oxide compared to HVOF-BC. The discontinuity of the TGO layer grown within the ceramic near the TC/BC region in APS-BC contains more spinel with crack nucleation, mostly associated with the mixed oxides. The greater thickness of mixed oxide in APS-BC promoted the crack propagation. Cracks are observed at the mixed oxides/TC region for both APS and HVOF bond coats. The formation of pores near NiO for APS-BC (C4 and C8) worsens the condition by acting as a fast track for oxygen diffusion into the interface region and leading to horizontal cracks. The porous layer of TGO (C4 and C8) makes the layer less resistant to crack propagation.

Figure 4.

Mixed oxide thickness ratio of APS-BC and HVOF-BC.

The HVOF-BC has less mixed oxide thickness ratio with slower growth of mixed oxide. Although the formation of spinel existed in HVOF-BC, all the samples were intact and did not fail due to the limited amount of mixed oxide ratio without the detrimental NiO. The TGO layer in HVOF-BC was very stable, remaining uniform and dense for up to 300 h of oxidation for both 1200 and 1300 °C.

3.3. Crack Propagation

Crack propagation occurs due to thermal stress in the substrate and coating being mismatched and growth of mixed oxides in the TGO layer by invasive BC oxidation that may lead to the failure of TBC. Since the crack length observed through SEM images does not always reveal the actual length of the crack, the 3D measuring laser microscope was more reliable in measuring the crack length of TBC. The multiple-point measurements with clearer DIC-supported images made the crack length measurement process easy and feasible.

Figure 5 illustrates the average crack length and TGO thickness in the TBCs at the oxidation time intervals, indicating the higher rate of crack propagation in APS-BC than in HVOF-BC. TGO thickness of HVOF-BC demonstrates a steady-state growth from 1200 to 1300 °C. Whereas APS-BC showed short steady-state growth up to 100 h of exposure and an accelerated steady-state growth thereafter. Thus, TGO in APS-BC formed much faster than in the HVOF-BC. This greater thickness in APS-BC than in HVOF-BC is due to the high content of the mixed oxide thickness ratio in APS-BC. The presence of mixed oxides with the addition of NiO which was absent in HVOF-BC was one of the causes of TGO thickening in APS-BC. Besides that, the discontinuous TGO layer with no oxidation resistance will not suppress the formation of detrimental oxides during prolonged thermal exposure, thus leading to TGO thickening. TGO thickening promotes stresses and accelerates generation of micro-cracks at TGO/TC interface, and thus, leads to spallation of TBC [30].

Figure 5.

Average crack length and TGO thickness of APS-BC and HVOF-BC for 1200 and 1300 °C with various oxidation times.

Although the TGO composition in the APS and HVOF bond coats varies, the crack length increases proportionally with TGO thickness in the two TGO systems. The crack lengths in the ceramic layer vary as small as 2 µm up to 30 µm, which are considered as short cracks compared to the conventional TBCs [38,39]. This is due to the addition of rare earth elements that induce lower thermal conductivity and improve the adhesion between TGO and TC where it provides great temperature drop and is resistant to cracking, thus leading to shorter crack lengths [7]. The HVOF BC has high oxidation resistance and good bonding with the TC layer. Choquet et al. mentioned that Ytrrium (rare earth element) in TC diffuses towards the external surface of BC at 1100 °C [40]. Simultaneously, the oxidation of BC occurs by predominant inward diffusion of oxygen with the internal oxidation of rare earth elements [40]. They found no voids or second phase at the TGO/BC interface. Hence, Choquet et al. concluded that good adhesion occurred after adding rare earth elements in TC [40]. However, APS-BC shows longer crack length in the coating compared to HVOF-BC, despite the same coating composition in both APS and HVOF bond coats. This is mainly due to the thick TGO owing to a high mixed-oxide ratio with predominantly NiO causing greater compressive stress and which is released by vertical cracks in the coating. Furthermore, Sun et al. mentioned that complicated local stress occurs near the irregular layer of TGO, causing micro-cracks in the coatings during high-temperature exposure [41], and additionally, that the growth of expanding new mixed oxides leads to in-plane elongation of lateral growth strain [42].

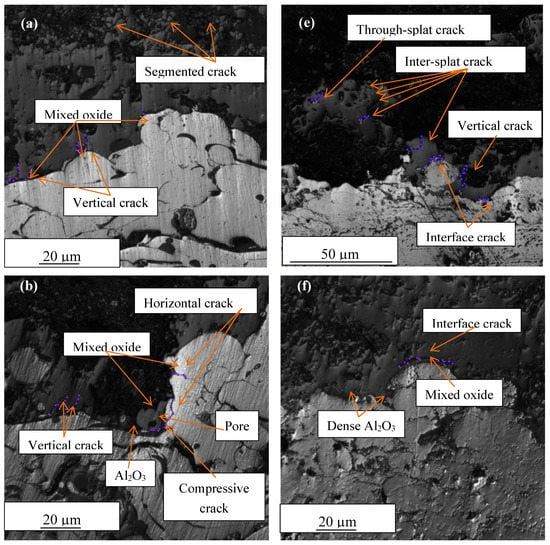

Figure 6 illustrates the laser images of the TC/BC interface of APS and HVOF bond coats. A few types of cracks were observed in the samples such as vertical crack, segmented crack, through-splat crack, inter-splat crack and horizontal crack. The type of cracks which existed in APS and HVOF bond coats are listed in Table 3. The TC contained more segmented and vertical cracks. Through-splat and inter-splat cracks were found in both TC and BC. Through-splat cracks are cracks that run through the splats and inter-splat cracks run across the splat interface. Through-splat cracks were found more in the APS bond coat than in HVOF due to its low velocity (120–600 m/s) during impact, resulting in partial melting of the particles. Vertical, interface and horizontal cracks dominated at the TGO region.

Figure 6.

Laser images of cross-sectional TC/BC interface thermally oxidized for APS-BC at (a) 1200 °C (1 h), (b) 1200 °C (300 h), (c) 1300 °C (1 h) and (d) 1300 °C (300 h), and HVOF-BC at (e) 1200 °C (1 h), (f) 1200 °C (300 h), (g) 1300 °C (1 h) and (h) 1300 °C (300 h).

The majority of the cracks observed originated from the region that contains mixed oxides, un-melted particles (Figure 6c–e) and pores (Figure 6b). Vertical cracks formed at the interface of TGO/TC in samples exposed with lower oxidation hour (1 h). Interface cracks followed the TGO layer from peak to valley and started to dominate at longer oxidation hours, mostly near the mixed oxide zone. The vertical cracks did not run through vertically to the underlying interface but instead, were terminated when they reached the interface. Only the horizontal crack propagates parallel to the interface direction and runs through the TGO layer for C4 and C8 at extended oxidation time (300 h). However, the horizontal crack did not reach the edge of the coating. Horizontal cracks produce higher compressive stress and release the stress by inducing compressive cracks. Compressive cracks are observed in C4 and C8 near the horizontal crack. Compressive cracks are cracks that occur due to compressive stress that nucleates from a horizontal crack [43] when the thickness of TGO grows vigorously due to a large amount of detrimental mixed oxides. Crack propagation revealed that the severe horizontal crack and compressive crack were found only in APS-BC where the presence of a large amount of mixed oxides was found with thick TGO growth, including spinel and NiO with pores.

3.4. Failure Mechanism

The TBC of APS-BC for 1200 and 1300 °C failed between 10 and 300 h (C2, C3, C4, C6, C7 and C8). The TC spall off within the TC slightly above the TGO layer, which is called the crack-susceptible zone (CSZ) [44]. The spallation of TC occurred away from the TC/BC interface, within the ceramic layer and not exactly at the interface region. The failure mechanism of TBC of sample C8 is shown in Figure 7a in the SEM image of C8 with a long horizontal crack with spalled coating. Figure 7b zoomed the SEM image at the CSZ layer and Figure 7c shows a diagram on the spalling failure mode in TBC.

Figure 7.

(a) SEM image of C8 (APS-BC, 1300 °C; 300 h) with a long horizontal crack with spalled coating, (b) zoomed SEM image at crack-susceptible zone (CSZ) layer and (c) diagram on spalling failure mode in TBC.

The CSZ are identified as weak locations for the TBCs and failures tend to occur at this zone during real service conditions [44]. The failure mechanism of TBCs with APS-BC comes from two distinct angles: (1) TGO growth and (2) TC thickness. The fast TGO growth rate of APS-BC with quick change from stable Al2O3 to a large amount of detrimental mixed oxides consisting of spinel and NiO leads to greater porosity and thickness of TGO than HVOF-BC. Mixed oxide structures are considered undesirable in a TBC system because it cannot form a continuous protective layer due to its poor adhesion and being aggravated by the consumption of alloy elements that stimulates degradation [35]. This leads to higher compressive stress within the TC near the TGO/TC interface. In order to release the stress, harmful horizontal and compressive cracks originate at exposed locations, such as un-melted particles and pores in APS-BC.

The thick (850 µm) TC also influences the failure mechanism. Thicker TCs are desirable for TBCs as they provide low thermal conductivity [5]. However, thick TCs increase the weight of the component and residual stress and this leads to a reduction in the heat transfer rate owing to the high conduction distance [5]. Hence, the surface temperature increases and exceeds the limit of ceramic material [5]. This sintering effect arises due to an increase in surface temperature which induces tensile stress away from the interface within the top coat. Mud-flat cracks along the splat boundaries appeared at the region to release the associated tensile stress and leads to loss of discrete segments [3]. Mud-flat cracks are only observed in Figure 3b,d (failed TBCs). According to Xie et al., the main reason for TBC failure is the fast growth of MO that generates severe tensile stress at the α-Al2O3/MO interface [45]. The tensile stress induces cracking in the TGO layer and further accelerates MO growth.

The compressive stress from the thick TGO and the tensile stress from the thick TC along the mud-flat cracks induce a disastrous horizontal crack that nucleates along the boundary of mud-flat cracks in the interface direction and run through the CSZ in APS-BC. As the oxidation time increases, the crack continuously propagates and reaches the edge of the coating and peels it off at CSZ.

On the other hand, all the layers of HVOF-BC remain intact from 1200 to 1300 °C for all oxidation hours (1–300 h). Although HVOF-BC also contains thick TC, it was intact and did not fail. This is due to the dense protective film of Al2O3 at the TGO layer that inhibits the diffusion of oxygen from TC and also the homogeneous distribution of lamellar structure by the HVOF method on BC. The results disclose that HVOF-BC tolerates thick TC while APS does not because of the effect of detrimental oxides in TGO.

4. Conclusions

TGO growth and crack propagation were studied via the thermal oxidation test using HVOF and APS bond coats. The APS-BC contains greater amounts of porosity than the HVOF-BC, and thus, leads to the formation of unstable Al2O3 and detrimental mixed oxides such as spinel and NiO in the TGO. The presence of spinel and NiO with more pores induced compressive stresses that caused the formation of horizontal and compressive cracks in the TGO layer. The thick TC increased the sintering effect during the higher oxidation hours (10–300 h) which caused tensile stress. The tensile stress was subsequently released in the form of mud-flat cracking near the TGO/TC interface. The compressive and tensile stresses prompted the formation of a long horizontal crack at the CSZ and caused spallation in the TBC of APS-BC. To the contrary, the HVOF-BC was observed to have an intact TBC due to its low mixed-oxide growth rate with a uniform and dense protective layer of stable Al2O3, which is more resistant to crack propagation. The findings show an increase in TBC durability. Therefore, HVOF-BC is more efficient in thick La–Gd–YSZ TBC. The surface roughness can be optimized and TC with columnar structure is used in order to improve the durability of thick TBC with APS-BC as a suggestion for further studies.

Author Contributions

All the authors have contributed to this research article such as: Conceptualization, S.M.Y. and A.M.; Data curation, S.M.Y.; Formal analysis, S.M. and N.M.A.; Funding acquisition, S.M.Y.; Investigation, S.M. and A.M.; Methodology, S.M., N.M.A., R.A.Z. and N.F.K.; Project administration, S.M.Y.; Resources, S.M.Y.; Software, S.M., N.M.A., R.A.Z. and N.F.K.; Validation, A.M.; Visualization, S.M.Y.; Writing–original draft, S.M.; Writing–review and editing, S.M. and A.M.

Funding

This research was funded by UNITEN R and D Sdn Bhd (No. U-SN-CR-18-01) and UNITEN UNIIG (No. J510050795). The APC was funded by UNITEN UNIIG (No. J510050795).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Universiti Tenaga Nasional, UNITEN R and D Sdn Bhd and Institute of Sustainable Energy of UNITEN for the lab facilities. Special thanks to those who contributed directly or indirectly to this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Manap, A.; Okabe, T.; Ogawa, K.; Mahalingam, S.; Abdullah, H. Experimental and smoothed particle hydrodynamics analysis of interfacial bonding between aluminum powder particles and aluminum substrate by cold spray technique. The Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 103, 4519–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.W. Thermal barrier coatings for gas turbines, automotive engines and diesel equipment. Mater. Des. 1992, 13, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.R.; Guilemany, J.M. Adhesion improvements of thermal barrier coatings with HVOF thermally sprayed bond coats. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 4694–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A. High Temperature Coatings; Butterworth-Heinemann: Burlington, VT, USA, 2017; pp. 170–171. [Google Scholar]

- Karaoglanli, A.C.; Ogawa, K.; Türk, A.; Ozdemir, I. Thermal shock and cycling behavior of thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) used in gas turbines. In Progress in Gas Turbine Performance; Benini, E., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; pp. 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Yang, L.; Wu, R.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huo, K.; Gan, M. Degradation mechanisms of air plasma sprayed free-standing yttria-stabilized zirconia thermal barrier coatings exposed to volcanic ash. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 481, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gok, M.G.; Goller, G. State of the art of gadolinium zirconate based thermal barrier coatings: Design, processing and characterization. In Coatings Technology; Samantara, A.K., Ratha, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, M.; Wang, J.; Kumar, R.; Roth, J.; Jiang, C.; Jordan, E.H. Higher temperature thermal barrier coatings with the combined use of yttrium aluminum garnet and the solution precursor plasma spray process. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2018, 27, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, J.G.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C. Porosity and its significance in plasma-sprayed coatings. Coatings 2019, 9, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, G.; Du, L.; Vaßen, R. Atmospheric plasma spraying of single phase lanthanum zirconate thermal barrier coatings with optimized porosity. Coatings 2016, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; He, L.; Mu, R.; Xu, Z.; Huang, G. A study of crack formation and propagation in LaZrCeO/YSZ thermal barrier coatings at different temperatures. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fei, J.; Guo, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B.; Yan, Z.; Ye, F. Thermal cycling and hot corrosion behavior of a novel LaPO4/YSZ double-ceramic-layer thermal barrier coating. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 8818–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Meng, G.H.; Yang, G.J.; Li, C.X.; Li, C.J. Dependence of scale thickness on the breaking behavior of the initial oxide on plasma spray bond coat surface during vacuum pre-treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 397, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swadźba, R. Interfacial phenomena and evolution of modified aluminide bondcoatings in thermal barrier coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 445, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, A.G.; Evans, A.G. Failure mechanisms associated with the thermally grown oxide in plasma-sprayed thermal barrier coatings. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 3963–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroonparvar, M.; Yajid, M.A.; Yusof, N.M.; Farahany, S.; Hussain, M.S.; Bakhsheshı-Rad, H.R.; Valefi, Z.; Abdolahi, A. Improvement of thermally grown oxide layer in thermal barrier coating systems with nano alumina as third layer. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2013, 23, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulci, G.; Tirillò, J.; Marra, F.; Sarasini, F.; Bellucci, A.; Valente, T.; Bartuli, C. High temperature oxidation of MCrAlY coatings modified by Al2O3 PVD overlay. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 268, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saral, U.; Toplan, N. Thermal cycle properties of plasma sprayed YSZ/Al2O3 thermal barrier coatings. Surf. Eng. 2009, 25, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Haynes, J.A.; Wang, H.; Lou, W.; Liu, X. Influences of Cr and Co on the growth of thermally grown oxide in thermal barrier coating during high-temperature exposure. Coatings 2018, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ming, C.; Zhong, X.H.; Ni, J.X.; Yang, J.S.; Tao, S.Y.; Zhou, F.F.; Wang, Y. Microstructure and self-healing properties of multi-layered NiCoCrAlY/TAZ/YSZ thermal barrier coatings fabricated by atmospheric plasma spraying. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 488, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, W.; Schaak, C.; Hagen, L.; Mauer, G.; Matthäus, G. Internal diameter coating processes for bond coat (HVOF) and thermal barrier coating (APS) systems. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2019, 28, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, X.-Y.; Dong, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Ren, K.; Sun, L. The Evaluation of durability of plasma-sprayed thermal barrier coatings with double-layer bond coat. Coatings 2019, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Chai, Y.; Li, Y. Oxidation Simulation of Thermal Barrier Coatings with Actual Microstructures Considering Strength Difference Property and Creep-Plastic Behavior. Coatings 2018, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lin Peng, R.; Li, X.-H.; Johansson, S. Investigation of Element Effect on High-Temperature Oxidation of HVOF NiCoCrAlX Coatings. Coatings 2018, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafsin, N.; Li, H.; Leib, E.W.; Vossmeyer, T.; Stroeve, P.; Castro, R.H. Stability of rare-earth-doped spherical yttria-stabilized zirconia synthesized by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 4425–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganvir, A.; Markocsan, N.; Joshi, S. Influence of isothermal heat treatment on porosity and crystallite size in axial suspension plasma sprayed thermal barrier coatings for gas turbine applications. Coatings 2017, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zou, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Z. Effect of internal oxidation on the interfacial morphology and residual stress in air plasma sprayed thermal barrier coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 334, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.R.; Wu, X.; Marple, B.R.; Patnaik, P.C. The growth and influence of thermally grown oxide in a thermal barrier coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Zulkifli, S.; Yajid, M.A.; Idris, M.H.; Daroonparvar, M.; Hamdan, H. TGO Formation with NiCoCrAlYTa bond coat deposition using APS and HVOF method. Adv. Mater. Res. 2015, 1125, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroonparvar, M.; Hussain, M.S.; Yajid, M.A. The role of formation of continues thermally grown oxide layer on the nanostructured NiCrAlY bond coat during thermal exposure in air. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 261, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, V. Aluminum-nickel-oxygen. In Ternary Alloys; Petzow, G., Effenberg, G., Eds.; VCH Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Hafskjold, B. Molecular dynamics simulations of yttrium-stabilized zirconia. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1995, 7, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, P.; Ericsson, T.; Wigren, J. Thermal shock testing of burner cans coated with a thick thermal barrier coating. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 1998, 7, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Liu, S.Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.G.; Zou, Z.W.; Li, X.W.; Wang, C.H. Microstructure and properties of HVOF-sprayed NiCrAlY coatings modified by rare earth. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2014, 23, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero-Martin, D.; Rad, M.R.; McDonald, A.; Hussain, T. Beyond traditional coatings: A review on thermal-sprayed functional and smart coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2019, 28, 598–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdelsztajn, L.; Picas, J.A.; Kim, G.E.; Bastian, F.L.; Schoenung, J.; Provenzano, V. Oxidation behavior of HVOF sprayed nanocrystalline NiCrAlY powder. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2002, 338, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaa, J.; Sfar, K.; Munz, D. Assessment of TBC systems failure mechanisms using a fracture mechanics approach. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 4399–43413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.R.; Irissou, E.; Wu, X.; Legoux, J.G.; Marple, B.R. The oxidation behavior of TBC with cold spray CoNiCrAlY bond coat. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2011, 20, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalanotti, G.; Xavier, J.; Camanho, P.P. Measurement of the compressive crack resistance curve of composites using the size effect law. Compos. Part A Appl. Sic. Manuf. 2014, 56, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choquet, P.; Indrigo, C.; Mevrel, R. Microstructure of oxide scales formed on cyclically oxidized M-Cr-Al-Y coatings. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1987, 88, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.J. Local stress evolution in thermal barrier coating system during isothermal growth of irregular oxide layer. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 216, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, T.J. Local stress around cap-like portions of anisotropically and nonuniformly grown oxide layer in thermal barrier coating system. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 5962–5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manero, A.; Sofronsky, S.; Knipe, K.; Meid, C.; Wischek, J.; Okasinski, J.; Almer, J.; Karlsson, A.M.; Raghavan, S. Monitoring local strain in a thermal barrier coating system under thermal mechanical gas turbine operating conditions. JOM J. Miner. Met. Mater. Soc. 2015, 67, 1528–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Fan, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Su, L.; Wang, T. Thermal-cycle dependent residual stress within the crack-susceptible zone in thermal barrier coating system. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101, 4256–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, W. Modelling of catastrophic stress development due to mixed oxide growth in thermal barrier coatings. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 11353–11361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).