High-Performance Silicon–Carbon Materials with High-Temperature Precursors for Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials Synthesis

2.2. Structural Characterization

2.3. Electrochemical Testing

2.3.1. Coin-Type Cells Test

2.3.2. Preparation of Full-Cell Electrodes, Cell Assembly and Electrochemical Performance Tests

3. Results and Discussion

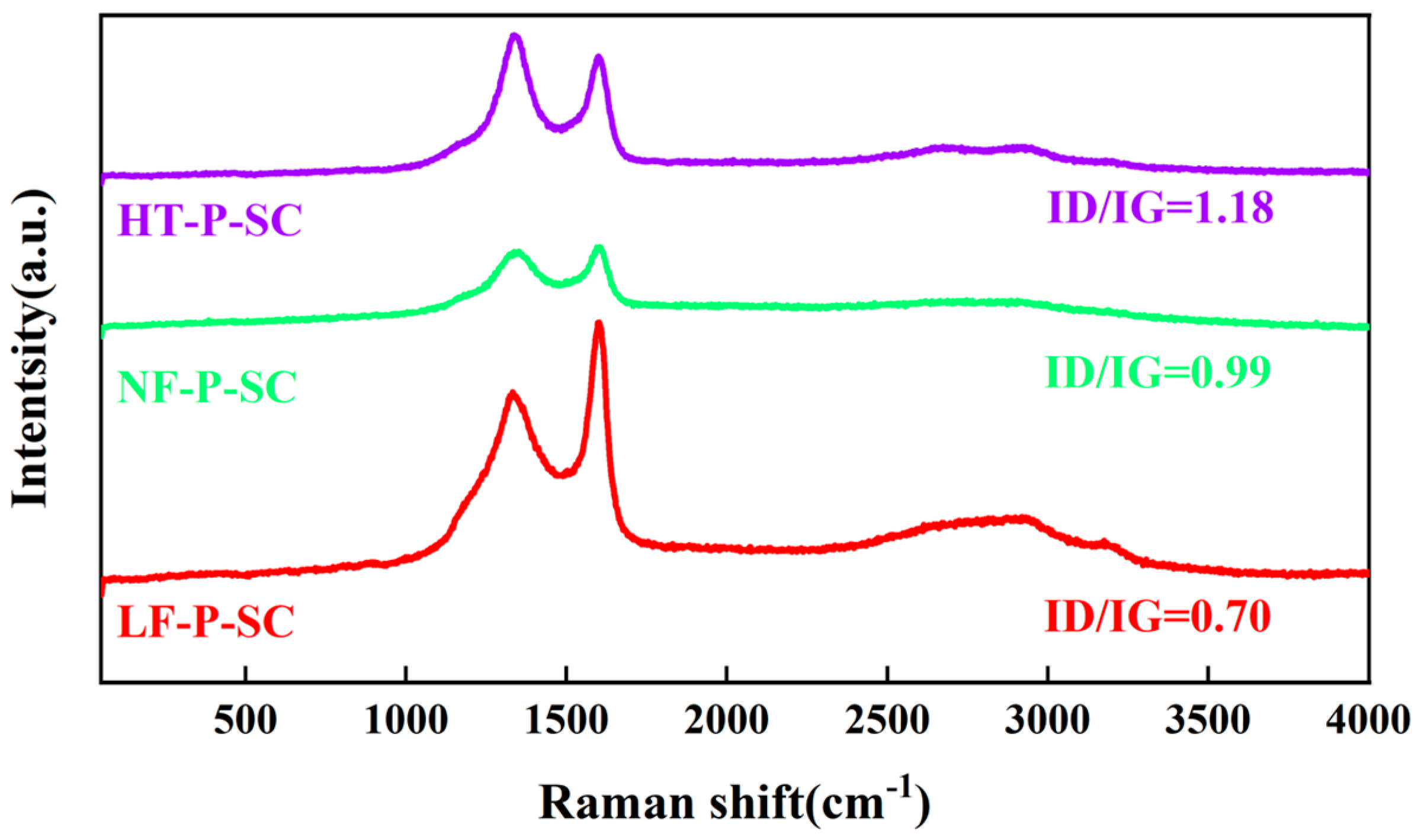

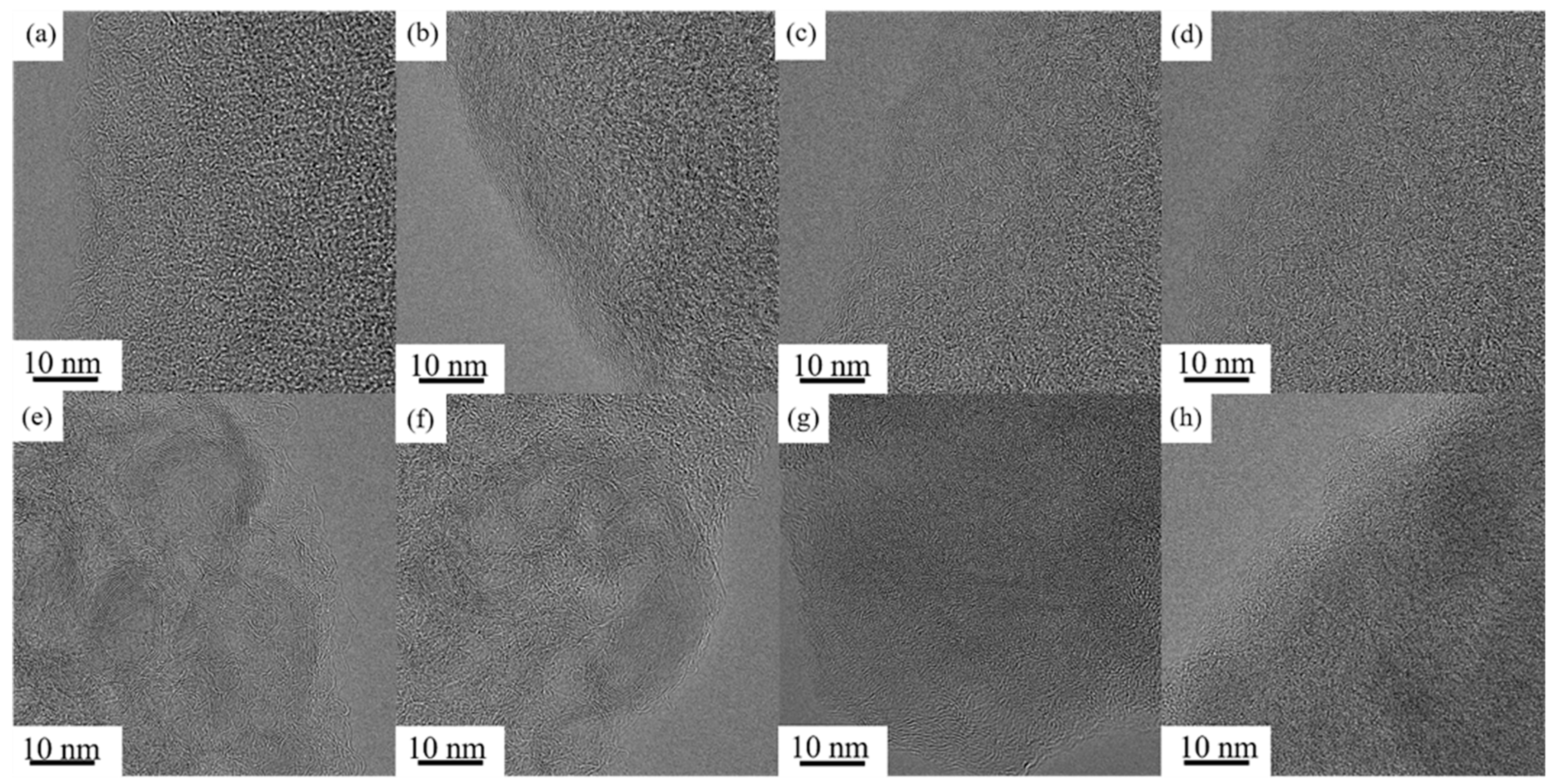

3.1. Microstructure and Morphology Characterization

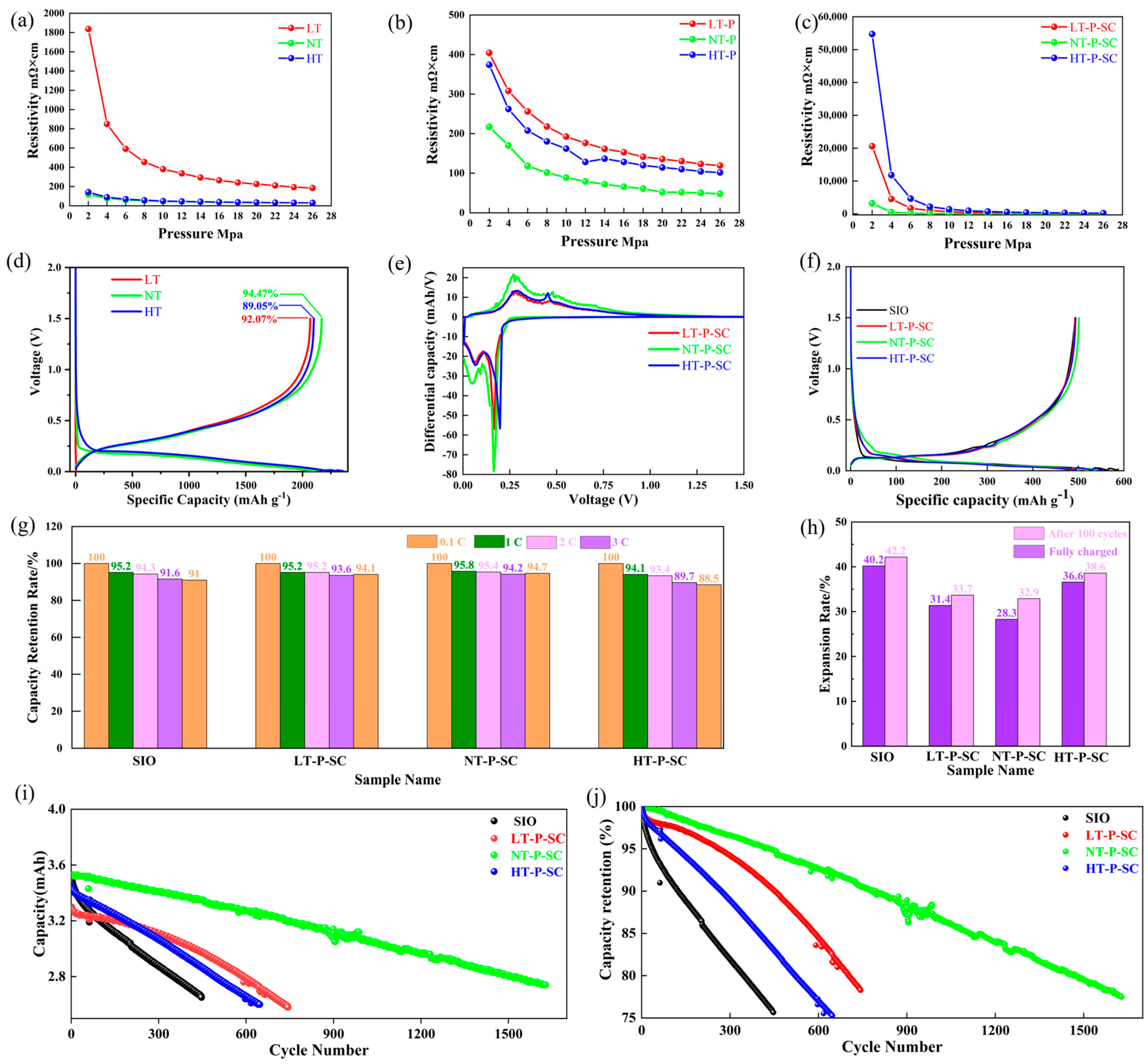

3.2. Electrochemical Performance Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Z.; Peng, W.; Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; Li, X.; Yan, G.; Wang, J. Review of silicon-based alloys for lithium-ion battery anodes. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2021, 28, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Mateen, A.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Bao, Z. Metal silicide-based anode materials: A review of their types, preparation and applications in energy storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shen, L.; Van Aken, P.A.; Maier, J.; Yu, Y. Dual-Functionalized Double Carbon Shells Coated Silicon Nanoparticles for High Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Tang, X.; Ge, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, F.; Bai, S. Si/C particles on graphene sheet as stable anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 80, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitew, Z.; Tesemma, M.; Beyene, Y.; Amare, M. Nano-structured silicon and silicon based composites as anode materials for lithium ion batteries: Recent progress and perspectives. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2022, 6, 1014–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Xia, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, X. Crystalline and amorphous carbon double-modified silicon anode: Towards large-scale production and superior lithium storage performance. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 229, 116054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, F.; Yang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Tang, W. Structural Control and Optimization Schemes of Silicon-Based Anode Materials. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 2201496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Peng, H.; Liu, G.; McIlwrath, K.; Zhang, X.F.; Huggins, R.A.; Cui, Y. High-performance lithium battery anodes using silicon nanowires. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laïk, B.; Eude, L.; Pereira-Ramos, J.-P.; Cojocaru, C.S.; Pribat, D.; Rouvière, E. Silicon nanowires as negative electrode for lithium-ion microbatteries. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 5528–5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.A.; Kilian, S.; Geaney, H.; Ryan, K.M. A Nanowire Nest Structure Comprising Copper Silicide and Silicon Nanowires for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes with High Areal Loading. Small 2021, 17, 2102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, G.; Sasaki, H.; Takahashi, H.; Sakaguchi, N. Solution-Plasma-Mediated Synthesis of Si Nanoparticles for Anode Material of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, T.; Li, D.; Yoshitake, H.; Wang, H. Effect of surface modification on electrochemical performance of nano-sized Si as an anode material for Li-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 34715–34723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, R.; Guo, H.; Li, X. Effects of lithium fluoride coating on the performance of nano-silicon as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 2016, 184, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galashev, A.Y.; Suzdaltsev, A.V.; Ivanichkina, K.A. Design of the high performance microbattery with silicene anode. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2020, 261, 114718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, F.; Xue, L.; Dang, D.; Liu, Q.; Ye, C.; Zhang, C.; Tan, J. Research progress on the structure design of nano-silicon anode for high-energy lithium-ion battery. Appl. Energy 2025, 390, 125820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.-C.; Su, Y.-F.; Chang, C.-C.; Hu, C.-W.; Chen, T.-Y.; Yang, S.-M.; Huang, J.-L. The synergistic effects of combining the high energy mechanical milling and wet milling on Si negative electrode materials for lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2017, 349, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohandehghan, A.; Cui, K.; Kupsta, M.; Memarzadeh, E.; Kalisvaart, P.; Mitlin, D. Nanometer-scale Sn coatings improve the performance of silicon nanowire LIB anodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 11261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Zhu, J.; Kang, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Fu, J.; Li, M.; Shi, C. In-situ mechanochemical synthesis of sub-micro Si/Sn@SiOx-C composite as high-rate anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 384, 138413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Jian, T.; Hou, J.; Zhou, J.; Xu, C. One-step mild fabrication of branch-like multimodal porous Si/Zn composites as high performance anodes for Li-ion batteries. Solid State Ion. 2020, 354, 115406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidas, N.; Shen, X.; Yuan, M.; Zhao, X.; Lehto, V.-P. Controlled surface oxidation of mesoporous silicon microparticles to achieve a stable Si/SiOx anode for lithium-ion batteries. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 344, 112243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Gao, X.; Wang, H.; Lin, Z.; Ling, M.; Liang, C. Millimeter Silicon-Derived Secondary Submicron Materials as High-Initial Coulombic Efficiency Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 10255–10260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Yang, F.; Lu, Z.; Xu, Z. A Design Strategy of Carbon Coatings on Silicon Nanoparticles as Anodes of High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 12143–12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Guo, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y. An alternative carbon source of silicon-based anode material for lithium ion batteries. Powder Technol. 2016, 295, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandan, R.; Takamori, N.; Higashimine, K.; Badam, R.; Matsumi, N. Black glasses grafted micron silicon: A resilient anode material for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 15960–15974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Pan, X.; Lin, W.; Zhang, H. Carbon-Covered Hollow Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanoparticles and Nitrogen-Doped Carbon-Covered Hollow Carbon Nanoparticles for Oxygen Reduction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 3487–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ji, W.; Liu, X. Scalable Synthesis of Pitch-Coated Nanoporous Si/Graphite Composite Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 4624–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, J.; Fang, Y.; Moriguchi, I.; Furó, I. Structural evolution by heat treatment of soft and hard carbons as Li storage materials: A joint NMR/XRD/TEM/Raman study. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 13962–13975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, I.-C.; Tran, N.T.; Knorr, D.B. Effects of high-temperature annealing on structural and mechanical properties of amorphous carbon materials investigated by molecular dynamics simulations. Carbon 2025, 234, 120006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Zhou, W.; Mo, Y.; Tang, R.; Duan, Y.; Hu, A.; Liu, J. Tuning hard carbon pore structure via water vapor activation for enhanced sodium-ion storage. Green Energy Environ. 2025, S2468025725003589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Pei, B.; Zhang, L.; Cao, X.; Liang, S. Pore structure in hard carbon: From recognition to regulation. Energy Storage Mater. 2025, 75, 104068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Liu, Q.; Li, H. Adsorption and Aggregation Behavior of Si, Sn, and Cu Atoms on Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) According to Classical Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Cai, Z.; Ma, Y.; Song, G.; Yang, W.; Wen, C.; Xie, Y. Enhanced electrochemical performance of silicon anode materials with titanium hydride treatment. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 933, 117292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zou, Y.; Huang, L.; Yin, H.; Xi, C.; Chen, X.; Shentu, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Lv, C.; et al. Enhanced electrochemical performance of sandwich-structured polyaniline-wrapped silicon oxide/carbon nanotubes for lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 442, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lu, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Lee, H.-W.; Yan, K.; Zhuo, D.; Lin, D.; Liu, N.; Cui, Y. Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphase-Protected LixSi Nanoparticles: An Efficient and Stable Prelithiation Reagent for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8372–8375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, G.; Qin, X.; Zou, J.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhu, H.; Chen, G.; Kang, F.; Li, B. Electrosprayed silicon-embedded porous carbon microspheres as lithium-ion battery anodes with exceptional rate capacities. Carbon 2018, 127, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tan, Y.; Li, P.; Xue, B.; Sun, J. Facile Synthesis of Double-Layer-Constrained Micron-Sized Porous Si/SiO2/C Composites for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 37732–37740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Shao, B.; Wang, Y.; Han, F. Solid-state silicon anode with extremely high initial coulombic efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, F.-R.; Dong, H.; Xu, B.; Yan, X. Facile preparation of silicon/carbon composite with porous architecture for advanced lithium-ion battery anode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 937, 117427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Fu, X.; Zhao, F.; Yu, L.; Su, W.; Wei, L.; Tang, G.; Wang, Y.; Wu, F.; Guo, X. Microsized Silicon/Carbon Composite Anodes through In Situ Polymerization of Phenolic Resin onto Silicon Microparticles for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 4989–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, K.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, A.; Chen, X.; Song, H. Graphene-doped silicon-carbon materials with multi-interface structures for lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 667, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Sun, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Shi, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Lv, R.; Jin, Z. Ladderlike polysilsesquioxanes derived dual-carbon-buffer-shell structural silicon as stable anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2024, 602, 234331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, B.; Zhan, Z.; Hu, M.; Cai, F.; Świerczek, K.; Yang, K.; Ren, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z. Boron-doped three-dimensional porous carbon framework/carbon shell encapsulated silicon composites for high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 664, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Porosity Proportion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Micropore (≤2 nm) | Mesoporous (2–50 nm) | Macropore (≥50 nm) |

| LT-P | 57.2% | 41.8% | 1.0% |

| NT-P | 65.6% | 34.2% | 0.3% |

| HT-P | 36.3% | 61.8% | 1.9% |

| Silicon–Carbon Anode | Current Density | Cycling Performance | ICE | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity Retention | Cycle | ||||

| NT-P-SC | 1 C | 80% | 1470 | 94.47% | This work |

| C@void/Si-G | 0.2 C | 90.1% | 100 | 83.3% | [38] |

| μSi@PF | 1 C | 87.7% | 100 | 80% | [39] |

| Si/G/P-10 | 85 mA/g | 95% | 100 | 75.7% | [40] |

| DCS-Si | 0.2 A/g | 50% | 300 | 91.8% | [41] |

| B-3DCF/Si@C | 400 mA/g | 89.1% | 150 | 75.2% | [42] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mei, H.; Yin, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, K.; Leng, J.; He, Z. High-Performance Silicon–Carbon Materials with High-Temperature Precursors for Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries. Coatings 2026, 16, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020188

Mei H, Yin Z, Wang S, Zhang K, Leng J, He Z. High-Performance Silicon–Carbon Materials with High-Temperature Precursors for Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries. Coatings. 2026; 16(2):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020188

Chicago/Turabian StyleMei, Hailong, Zhixiao Yin, Shuai Wang, Kui Zhang, Jiugou Leng, and Ziguo He. 2026. "High-Performance Silicon–Carbon Materials with High-Temperature Precursors for Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries" Coatings 16, no. 2: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020188

APA StyleMei, H., Yin, Z., Wang, S., Zhang, K., Leng, J., & He, Z. (2026). High-Performance Silicon–Carbon Materials with High-Temperature Precursors for Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries. Coatings, 16(2), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020188