Thin-Film Sensors for Industry 4.0: Photonic, Functional, and Hybrid Photonic-Functional Approaches to Industrial Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of Photonic Thin Films

2.1. Optical Principles

2.2. Deposition Techniques

2.3. Material Platforms

2.4. Integration Approaches

3. Thin Film Photonic Sensors for Industrial Applications

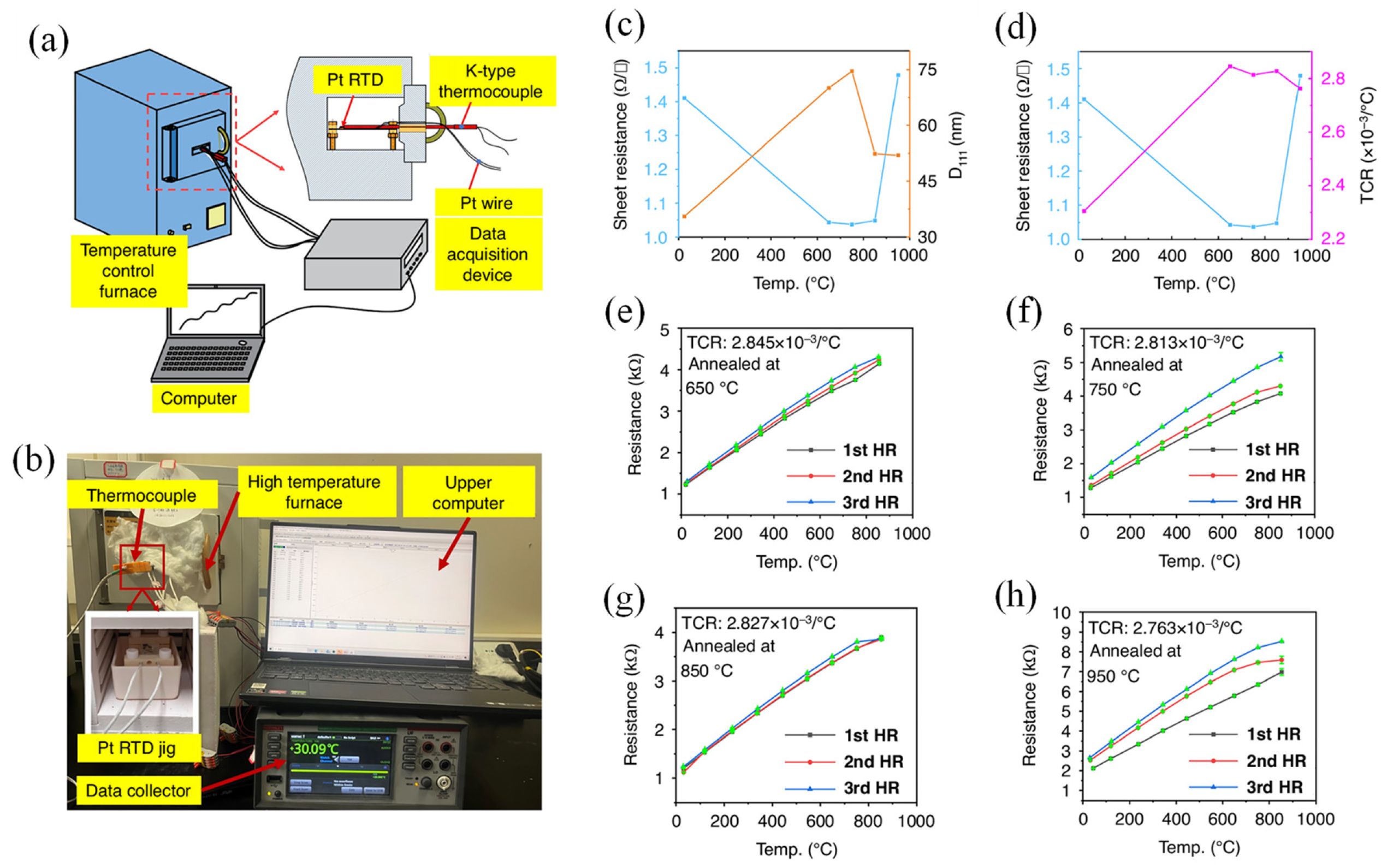

3.1. Temperature Monitoring

3.2. Strain and Stress Monitoring

3.3. Chemical Leakage Detection

3.4. Safety and Hazard Monitoring

4. Industrial Integration and Smart Manufacturing

4.1. Role of Thin-Film Sensors in Industry 4.0 and IoT

4.2. Wireless and Remote Sensing Capabilities

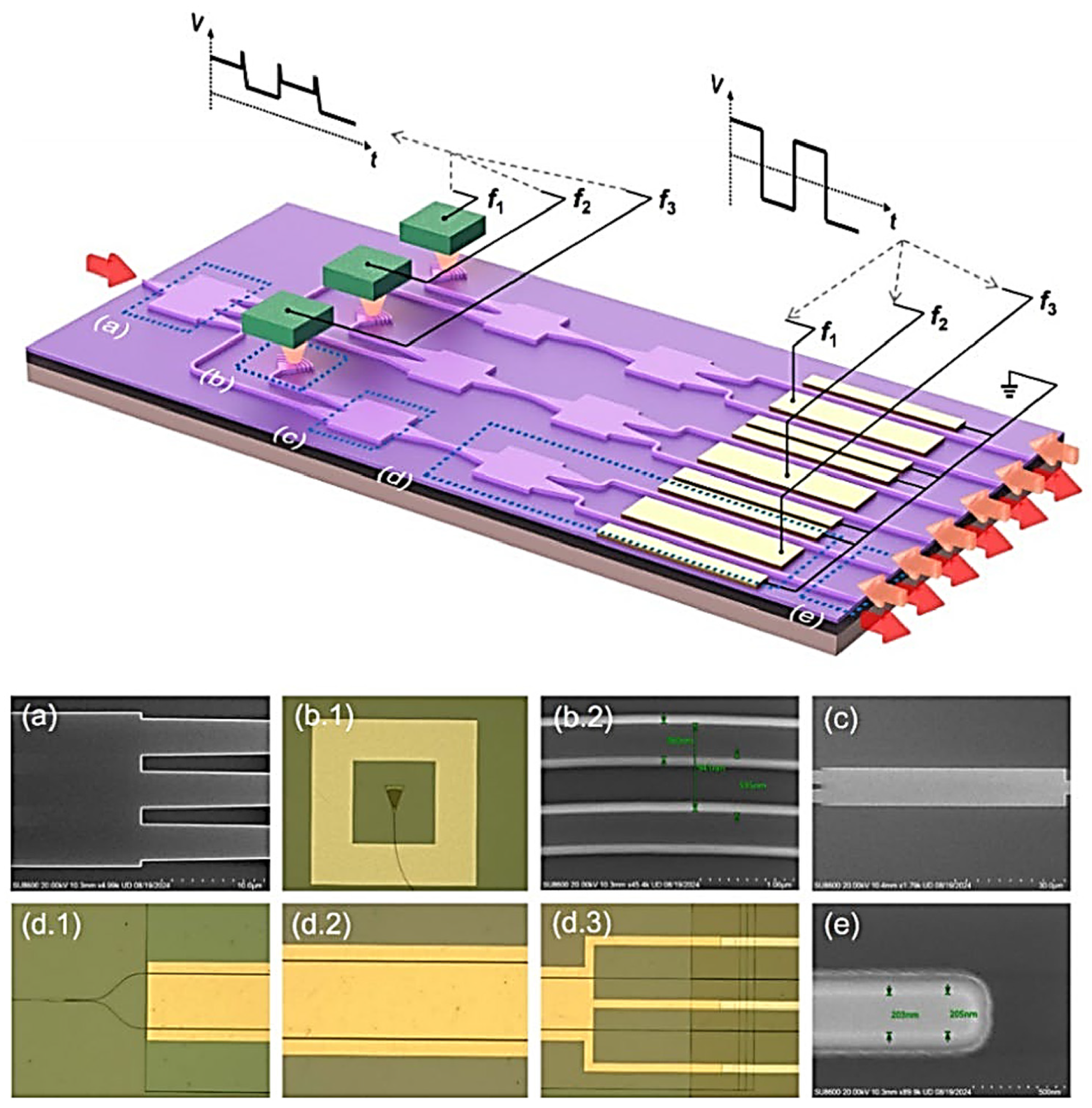

4.3. On-Chip Integration with Photonic Circuits

5. Challenges and Limitations

5.1. Harsh Environment Durability

5.2. Fabrication Scalability and Reproducibility

5.3. Signal Stability and Cross-Sensitivity

5.4. Packaging and Integration with Industrial Hardware

6. Emerging Trends

7. Summary and Outlook

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Folgado, F.J.; Calderón, D.; González, I.; Calderón, A.J. Review of Industry 4.0 from the Perspective of Automation and Supervision Systems: Definitions, Architectures and Recent Trends. Electronics 2024, 13, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S.; Ambad, P.; Bhosle, S. Industry 4.0—A Glimpse. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 20, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrašinović, A.; Đurđević, T.; Nešković, J.; Radosavljević, M. Temperature Monitoring in Metal Additive Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 4.0. Technologies 2025, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Internet of Things for Smart Factories in Industry 4.0, a Review. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liehr, S. Polymer Optical Fiber Sensors in Structural Health Monitoring. In New Developments in Sensing Technology for Structural Health Monitoring; Mukhopadhyay, S.C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 297–333. ISBN 978-3-642-21099-0. [Google Scholar]

- Golovastikov, N.V.; Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N. Optical Fiber-Based Structural Health Monitoring: Advancements, Applications, and Integration with Artificial Intelligence for Civil and Urban Infrastructure. Photonics 2025, 12, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, T.; Ramzan, N.; Ahmed, S.; Ur-Rehman, M. Advances in Sensor Technologies in the Era of Smart Factory and Industry 4.0. Sensors 2020, 20, 6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Rab, S.; Suman, R. Significance of Sensors for Industry 4.0: Roles, Capabilities, and Applications. Sens. Int. 2021, 2, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhussain, S.H.; Mahmmod, B.M.; Alwhelat, A.; Shehada, D.; Shihab, Z.I.; Mohammed, H.J.; Abdulameer, T.H.; Alsabah, M.; Fadel, M.H.; Ali, S.K.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Sensor Technologies in IoT: Technical Aspects, Challenges, and Future Directions. Computers 2025, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, A.; Rekowski, M.; Timmann, F.; Herrmann, C.; Dröder, K. Development of Thin-Film Sensors for In-Process Measurement during Injection Molding. Procedia CIRP 2023, 120, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthumalai, K.; Gokila, N.; Haldorai, Y.; Rajendra Kumar, R.T. Advanced Wearable Sensing Technologies for Sustainable Precision Agriculture—A Review on Chemical Sensors. Adv. Sens. Res. 2024, 3, 2300107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Liang, K.; Ma, Y.; Geng, T. A Fabry-Perot Interferometer Based on Probe-Embedded Bubble for Ultrasensitive Strain Measurement. Measurement 2025, 239, 115505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Singh, S.; Chawla, V.; Chawla, P.A.; Bhatia, R. Surface Plasmon Resonance as a Fascinating Approach in Target-Based Drug Discovery and Development. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 171, 117501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Song, H.; Choi, J.; Kim, K. A Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Using Double-Metal-Complex Nanostructures and a Review of Recent Approaches. Sensors 2018, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Khan, Y.; Irfan, M.; Choudri, S.; Khonina, S.N.; Kazanskiy, N.L.; Butt, M.A. Three-Dimensional Modeling of the Optical Switch Based on Guided-Mode Resonances in Photonic Crystals. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, H.; Hakim, L.; Boonruang, S.; Mohammed, W.S.; Hsu, S.H. Polymer-Based Guided-Mode Resonance Sensors: From Optical Theories to Sensing Applications. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 9700–9713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, G.; Kong, H.; Yang, G.; Wei, G.; Zhou, X. Recent Advances in Photonic Crystal-Based Sensors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 475, 214909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A. Butt Thin-Film Coating Methods: A Successful Marriage of High-Quality and Cost-Effectiveness—A Brief Exploration. Coatings 2022, 12, 1115. [Google Scholar]

- Vitoria, I.; Gallego, E.E.; Melendi-Espina, S.; Hernaez, M.; Ruiz Zamarreño, C.; Matías, I.R. Gas Sensor Based on Lossy Mode Resonances by Means of Thin Graphene Oxide Films Fabricated onto Planar Coverslips. Sensors 2023, 23, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.A. Photonics on a Budget: Low-Cost Polymer Sensors for a Smarter World. Micromachines 2025, 16, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.A.; Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N.; Voronkov, G.S.; Grakhova, E.P.; Kutluyarov, R.V. A Review on Photonic Sensing Technologies: Status and Outlook. Biosensors 2023, 13, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, S.; Biondi, A.M.; Wu, R.; Cao, L.; Wang, X. Structural Health Monitoring Using a New Type of Distributed Fiber Optic Smart Textiles in Combination with Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry (OFDR): Taking a Pedestrian Bridge as Case Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Mateos, X.; Piramidowicz, R. Photonics Sensors: A Perspective on Current Advancements, Emerging Challenges, and Potential Solutions (Invited). Phys. Lett. A 2024, 516, 129633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhu, Z.; Su, Z.; Yao, W.; Zheng, S.; Wang, P. Optical Fiber Sensors in Infrastructure Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review. Intell. Transp. Infrastruct. 2023, 2, liad018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neogi, S.; Ghosh, R. Metal-Oxide Gas Sensors (SnO2, Fe2O3, TiO2, CoO, ZnO, NiO, CuO, and Perovskite Oxides). In Electric and Electronic Applications of Metal Oxides; Moharana, S., Sahu, B.B., Satpathy, S.K., Nguyen, T.A., Eds.; Metal Oxides; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 333–348. ISBN 978-0-443-26554-9. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, Y. Recent Advances in SnO2 Nanostructure Based Gas Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 364, 131876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhao, R.; Yao, L.; Ran, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. A Review on WO3 Based Gas Sensors: Morphology Control and Enhanced Sensing Properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 820, 153194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.M.; Dinan, B.; Akbar, S.A.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A. Gas Sensors Based on One Dimensional Nanostructured Metal-Oxides: A Review. Sensors 2012, 12, 7207–7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A. A Novel Plasmonic Waveguide for Extraordinary Field Enhancement of Spoof Surface Plasmon Polaritons with Low-Loss Feature. Results Opt. 2021, 5, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldewachi, H.; Chalati, T.; Woodroofe, M.N.; Bricklebank, N.; Sharrack, B.; Gardiner, P. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Biosensors. Nanoscale 2017, 10, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X. Graphene-Based Biosensors for Detection of Biomarkers. Micromachines 2020, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.A. Graphene in Photonic Sensing: From Fundamentals to Cutting-Edge Applications. Fundam. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

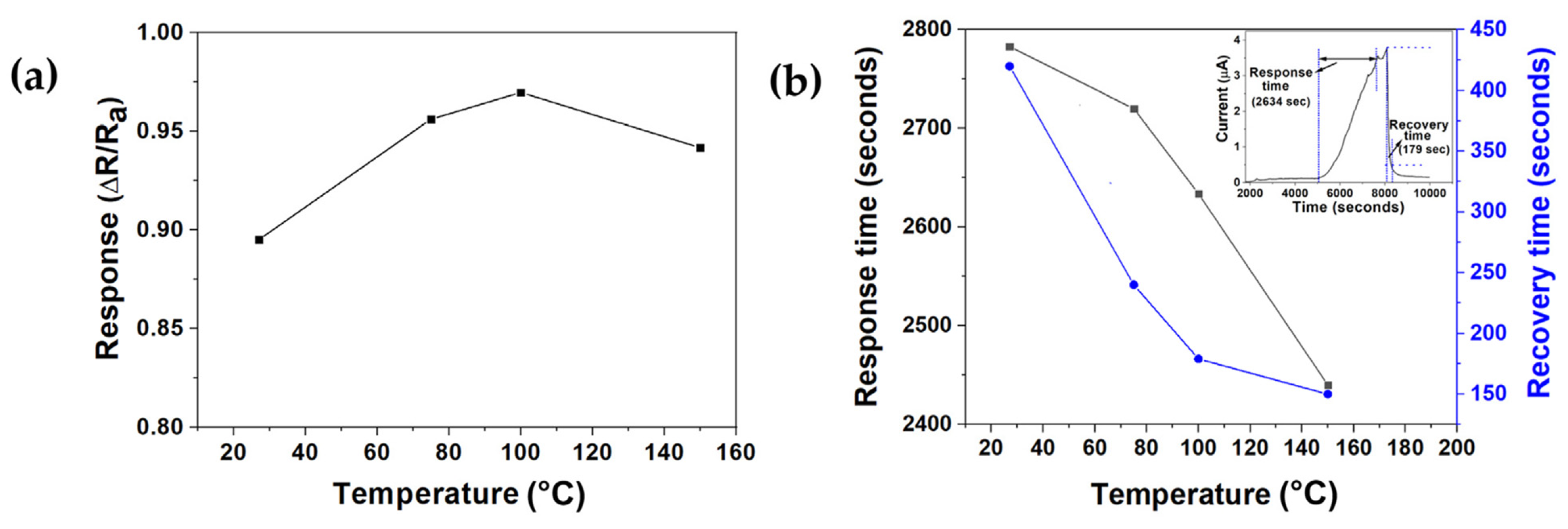

- Tagbo, P.C.; Mohamed, M.M.; Ayad, M.M.; El-Moniem, A.A. Fabrication of Flexible MoS2 Sensors for High-Performance Detection of Ethanol Vapor at Room Temperature. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2025, 389, 116531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Fröch, J.E.; Christian, J.; Straw, M.; Bishop, J.; Totonjian, D.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Toth, M.; Aharonovich, I. Photonic Crystal Cavities from Hexagonal Boron Nitride. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bystrický, R.; Tiwari, S.K.; Hutár, P.; Sýkora, M. Thermal Stability of Chalcogenide Perovskites. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 12826–12838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xue, C.; Zhang, W.; Yu, L.; Wang, Q.; Que, W.; Wang, Y.; Hu, F. Multifunctional TiO2/Ormosils Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Films Derived by a Sol-Gel Process for Photonics and UV Nanoimprint Applications. Opt. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, J.E. Chemical Methods of Thin Film Deposition: Chemical Vapor Deposition, Atomic Layer Deposition, and Related Technologies. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2003, 21, S88–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Kim, K.S. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Graphene and Its Characterizations and Applications. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2024, 61, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliaev, L.Y.; Shkondin, E.; Lavrinenko, A.V.; Takayama, O. Optical, Structural and Composition Properties of Silicon Nitride Films Deposited by Reactive Radio-Frequency Sputtering, Low Pressure and Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition. Thin Solid Films 2022, 763, 139568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, Y.; Zheng, L.; Steinbach, L.; Günther, A.; Schneider, A.; Roth, B. Low-Cost Scalable Fabrication of Functionalized Optical Waveguide Arrays for Gas Sensing Application. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Sierra, J.; Martínez, A.; Etxarri, I.; Azpitarte, I.; Pozo, B.; Quintana, I. Manufacturing Smart Surfaces with Embedded Sensors via Magnetron Sputtering and Laser Scribing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 606, 154844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plogmeyer, M.; González, G.; Pongratz, C.; Schott, A.; Schulze, V.; Bräuer, G. Tool-Integrated Thin-Film Sensor Systems for Measurement of Cutting Forces and Temperatures during Machining. Prod. Eng. 2024, 18, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langat, R.K.; De Luycker, E.; Cantarel, A.; Rakotondrabe, M. Integration Technology with Thin Films Co-Fabricated in Laminated Composite Structures for Defect Detection and Damage Monitoring. Micromachines 2024, 15, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Sicard, B.; Gadsden, S.A. Physics-Informed Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Review on Applications in Anomaly Detection and Condition Monitoring. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.; Kumar, R.; Goel, N. Chemiresistive Gas Sensors beyond Metal Oxides: Using Ultrathin Two-Dimensional Nanomaterials. FlatChem 2024, 43, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzoni, A. Metal Oxide Chemiresistors: A Structural and Functional Comparison between Nanowires and Nanoparticles. Sensors 2022, 22, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Cai, Y.; Jia, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yue, T.; Zhong, S. High-Performance Piezoresistive Sensor Based on Indium Tin Oxide Nanoparticles/Cellulose Nanofiber Composite for Human Activity Monitoring. Compos. Commun. 2025, 59, 102544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Niu, H.; Kim, E.-S.; Shin, Y.K.; Li, Y.; Kim, N.-Y. Advanced Polymer Materials-Based Electronic Skins for Tactile and Non-Contact Sensing Applications. InfoMat 2023, 5, e12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, X.; Song, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xiong, C.; Shi, Z. Flexible and Ultrasensitive Piezoresistive Electronic Skin Based on Chitin/Sulfonated Carbon Nanotube Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, J.-M.; Collar, E.P. Current and Future Insights in Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mi, B.; Ma, X.; Liu, P.; Ma, F.; Zhang, K.; Chen, X.; Li, W. Review of Thin-Film Resistor Sensors: Exploring Materials, Classification, and Preparation Techniques. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Sensors: A Review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 182, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Yan, D. Glassy Inorganic-Organic Hybrid Materials for Photonic Applications. Matter 2024, 7, 1950–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picelli, L.; van Veldhoven, P.J.; Verhagen, E.; Fiore, A. Hybrid Electronic–Photonic Sensors on a Fibre Tip. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2023, 18, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosa, M.; Bolognesi, M.; Fornasari, L.; Grasso, G.; Lopez-Sanchez, L.; Marabelli, F.; Toffanin, S. Nanostructured Organic/Hybrid Materials and Components in Miniaturized Optical and Chemical Sensors. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmer, G.H.; Huang, H.; Roland, C. Thin Film Deposition: Fundamentals and Modeling. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1998, 12, 354–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poenar, D.P.; Wolffenbuttel, R.F. Thin-Film Optical Sensors with Silicon-Compatible Materials. Appl. Opt. 1997, 36, 5109–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, T.I.; Afsheen, S.; Kausar, S. Fundamentals of Thin Film. In Thin Film Deposition Techniques: Thin Film Deposition Techniques and Its Applications in Different Fields; Awan, T.I., Afsheen, S., Kausar, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1–29. ISBN 978-981-96-1364-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R.C.; Parpia, M.; Hupp, J.T. Sensing via Optical Interference. Mater. Today 2005, 8, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y. Direct and Inverse Scattering in an Optical Waveguide. Inverse Probl. 2024, 40, 125010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Xu, W.; Song, B.; Sheng, J.; He, M.; Shi, H. A Reusable Evanescent Wave Immunosensor for Highly Sensitive Detection of Bisphenol A in Water Samples. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, N.A.; Rogers, P.H.; Nandasiri, M.I.; Thevuthasan, S.; Carpenter, M.A. Plasmonic-Based Sensing Using an Array of Au–Metal Oxide Thin Films. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 10437–10444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andam, N.; Refki, S.; Hayashi, S.; Sekkat, Z. Plasmonic Mode Coupling and Thin Film Sensing in Metal–Insulator–Metal Structures. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, F.; Regalado, L.E.; Ramos-Mendieta, F.; Gaspar-Armenta, J.; Lopez-Ríos, T. Photonic Crystal Sensor Based on Surface Waves for Thin-Film Characterization. Opt. Lett. 2002, 27, 646–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarinathan, J.; Bakhtazad, A.; Poulsen, B.; Zylstra, M. Photonic Crystal Thin-Film Micro-Pressure Sensors. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2015, 619, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.; Reynaud, M.; Posadas, A.B.; Zhan, X.; Warner, J.H.; Demkov, A.A. Electro-Optic Effect in Thin Film Strontium Barium Niobate (SBN) Grown by RF Magnetron Sputtering on SrTiO3 Substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 136, 013102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säynätjoki, A.; Karvonen, L.; Alasaarela, T.; Tu, X.; Liow, T.Y.; Hiltunen, M.; Tervonen, A.; Lo, G.Q.; Honkanen, S. Low-Loss Silicon Slot Waveguides and Couplers Fabricated with Optical Lithography and Atomic Layer Deposition. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 26275–26282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasaarela, T.; Korn, D.; Alloatti, L.; Säynätjoki, A.; Tervonen, A.; Palmer, R.; Leuthold, J.; Freude, W.; Honkanen, S. Reduced Propagation Loss in Silicon Strip and Slot Waveguides Coated by Atomic Layer Deposition. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 11529–11538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasinski, P.; Zieba, M.; Gondek, E.; Niziol, J.; Gorantla, S.; Rola, K.; Bachmatiuk, A.; Tyszkiewicz, C. Sol-Gel Derived Silica-Titania Waveguide Films for Applications in Evanescent Wave Sensors—Comprehensive Study. Materials 2022, 15, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Optical Properties and Applications of Molybdenum Disulfide/SiO2 Saturable Absorber Fabricated by Sol-Gel Technique. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 6348–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.A.; Tyszkiewicz, C.; Karasiński, P.; Zięba, M.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Zdończyk, M.; Duda, Ł.; Guzik, M.; Olszewski, J.; Martynkien, T.; et al. Optical Thin Films Fabrication Techniques—Towards a Low-Cost Solution for the Integrated Photonic Platform: A Review of the Current Status. Materials 2022, 15, 4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C. Review of Chemical Vapor Deposition of Graphene and Related Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2329–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, N.J.; Smith, M.A.A.; Kay, R.W.; Harris, R.A. A Review of Aerosol Jet Printing—A Non-Traditional Hybrid Process for Micro-Manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 105, 4599–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.; Skolrood, L.N.; Li, K.; Joshi, P.C.; Aytug, T. Aerosol-Jet Printed Sensors for Environmental, Safety, and Health Monitoring: A Review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2300030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, B.; Beynon, D.; Phillips, C.; Deganello, D. Printed-Sensor-on-Chip Devices—Aerosol Jet Deposition of Thin Film Relative Humidity Sensors onto Packaged Integrated Circuits. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, A.; Silva, F.J.G.; Porteiro, J.; Míguez, J.L.; Pinto, G.; Fernandes, L. On the Physical Vapour Deposition (PVD): Evolution of Magnetron Sputtering Processes for Industrial Applications. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 17, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.; Myśliwiec, J. Recent Advances in Magnetron Sputtering: From Fundamentals to Industrial Applications. Coatings 2025, 15, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.M. Atomic Layer Deposition: An Overview. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chai, G.; Wang, X. Atomic Layer Deposition of Thin Films: From a Chemistry Perspective. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 2023, 5, 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, G. Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition of Organic Polymers. Processes 2021, 9, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Fischer, T.; Mathur, S. Field-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition: New Perspectives for Thin Film Growth. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 20104–20142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasri, R.; Soma Raju, K.R.C.; Samba Sivudu, K. 12-Applications of Sol–Gel Coatings: Past, Present, and Future. In Handbook of Modern Coating Technologies; Aliofkhazraei, M., Ali, N., Chipara, M., Bensaada Laidani, N., De Hosson, J.T.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 425–451. ISBN 978-0-444-63237-1. [Google Scholar]

- Werum, K.; Mueller, E.; Keck, J.; Jaeger, J.; Horter, T.; Glaeser, K.; Buschkamp, S.; Barth, M.; Eberhardt, W.; Zimmermann, A. Aerosol Jet Printing and Interconnection Technologies on Additive Manufactured Substrates. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valayil Varghese, T.; Eixenberger, J.; Rajabi-Kouchi, F.; Lazouskaya, M.; Francis, C.; Burgoyne, H.; Wada, K.; Subbaraman, H.; Estrada, D. Multijet Gold Nanoparticle Inks for Additive Manufacturing of Printed and Wearable Electronics. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khorin, P.A.; Khonina, S.N. Biochips on the Move: Emerging Trends in Wearable and Implantable Lab-on-Chip Health Monitors. Electronics 2025, 14, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckingbottom, R.; Todd, C.J.; Davies, G.J. The Interplay of Thermodynamics and Kinetics in Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) of Doped Gallium Arsenide. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1980, 127, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahi, H.; Horikoshi, Y. General Description of MBE. In Molecular Beam Epitaxy: Materials and Applications for Electronics and Optoelectronics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 23–39. ISBN 978-1-119-35500-7. [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, R.F.C.; Harp, G.R.; Weller, D.K.; Marks, R.F.; Toney, M.F.; Cebollada, A.; Rabedeau, T.A. Molecular-Beam Epitaxy (MBE) Growth of Chemically Ordered Co-Pt and Fe-Pt Alloy Phases. In Proceedings of the Epitaxial Growth Processes; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1994; Volume 2140, pp. 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, M.A. Integrated Optics: Platforms and Fabrication Methods. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognetti, J.S.; Moen, M.T.; Brewer, M.G.; Bryan, M.R.; Tice, J.D.; McGrath, J.L.; Miller, B.L. A Photonic Biosensor-Integrated Tissue Chip Platform for Real-Time Sensing of Lung Epithelial Inflammatory Markers. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Oseledets, I.V.; Nikonorov, A.V.; Chertykovtseva, V.O.; Khonina, S.N. Exploring the Frontier of Integrated Photonic Logic Gates: Breakthrough Designs and Promising Applications. Technologies 2025, 13, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.X.J. Doped Zinc Oxide-Based Piezoelectric Devices for Energy Harvesting and Sensing. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 6, 2500017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, K.; Han, X.F.; Guenther, K.H. Comparative Study of Titanium Dioxide Thin Films Produced by Electron-Beam Evaporation and by Reactive Low-Voltage Ion Plating. Appl. Opt. 1993, 32, 5594–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, X.; Su, L.; Ma, D.; Lai, T.; Yao, L.; Xiao, X.; Wang, Y. SnO2 Nanostructured Materials Used as Gas Sensors for the Detection of Hazardous and Flammable Gases: A Review. Nano Mater. Sci. 2022, 4, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Guo, X.; Nie, L.; Wu, X.; Peng, L.; Chen, J. A Review on WO3 Gasochromic Film: Mechanism, Preparation and Properties. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 2442–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafraniak, B.; Fuśnik, Ł.; Xu, J.; Gao, F.; Brudnik, A.; Rydosz, A. Semiconducting Metal Oxides: SrTiO3, BaTiO3 and BaSrTiO3 in Gas-Sensing Applications: A Review. Coatings 2021, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, C.; Benwadih, M.; Revenant, C. Sol–Gel Derived Barium Strontium Titanate Thin Films Using a Highly Diluted Precursor Solution. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 085302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefnia, F.; Zibaii, M.I.; Layeghi, A.; Rostami, S.; Babakhani-Fard, M.-M.; Moghadam, F.M. Citrate Polymer Optical Fiber for Measuring Refractive Index Based on LSPR Sensor. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baburin, A.S.; Merzlikin, A.M.; Baryshev, A.V.; Ryzhikov, I.A.; Panfilov, Y.V.; Rodionov, I.A. Silver-Based Plasmonics: Golden Material Platform and Application Challenges [Invited]. Opt. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 611–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.; Troc, N.; Cottancin, E.; Pellarin, M.; Weissker, H.-C.; Lermé, J.; Kociak, M.; Hillenkamp, M. Plasmonic Quantum Size Effects in Silver Nanoparticles Are Dominated by Interfaces and Local Environments. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur’aini, A.; Oh, I. Volatile Organic Compound Gas Sensors Based on Methylammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite Operating at Room Temperature. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 12982–12987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.R.; Singh, P.D.D.; Harshita; Basu, H.; Choi, Y.; Murthy, Z.V.P.; Park, T.J.; Kailasa, S.K. Single Crystal Perovskites: Synthetic Strategies, Properties and Applications in Sensing, Detectors, Solar Cells and Energy Storage Devices. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 519, 216105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, J.; Zeng, M.; Fu, L. Space-Confined Growth of Metal Halide Perovskite Crystal Films. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 1609–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demontis, V.; Durante, O.; Marongiu, D.; De Stefano, S.; Matta, S.; Simbula, A.; Ragazzo Capello, C.; Pennelli, G.; Quochi, F.; Saba, M.; et al. Photoconduction in 2D Single-Crystal Hybrid Perovskites. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2402469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A. Beyond the Detection Limit: A Review of High-Q Optical Ring Resonator Sensors. Mater. Today Phys. 2025, 58, 101873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Chen, Y.-J.; Wu, D.-S.; Huang, W.-H.; Wang, C.-T. High-Sensitivity Silicon Nitride Optical Temperature Sensor Based on Cascaded Mach-Zehnder Interferometers. Opt. Mater. 2025, 165, 117139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta-Chaudhuri, T.; Abshire, P.; Smela, E. Packaging Commercial CMOS Chips for Lab on a Chip Integration. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonopera, M. Fiber-Bragg-Grating-Based Displacement Sensors: Review of Recent Advances. Materials 2022, 15, 5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.-C.; Leng, Y.-K.; Liao, Y.-C.; Liu, B.; Luo, W.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.-L.; Yuan, J.; Xu, H.-Y.; Xiong, Y.-H.; et al. Tapered Microfiber MZI Biosensor for Highly Sensitive Detection of Staphylococcus Aureus. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 5531–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun Kumela, A.; Belay Gemta, A.; Kebede Hordofa, A.; Birhanu, R.; Dagnaw Mekonnen, H.; Sherefedin, U.; Weldegiorgis, K. A Review on Hybridization of Plasmonic and Photonic Crystal Biosensors for Effective Cancer Cell Diagnosis. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 6382–6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Chen, Y.; He, J.; Occhipinti, L.G.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X. Two-Dimensional Material-Enhanced Surface Plasmon Resonance for Antibiotic Sensing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 455, 131644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Li, M.; Li, M.-Y.; Wen, X.; Deng, S.; Liu, S.; Lu, H. Sensitivity Enhancement of 2D Material-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor with an Al–Ni Bimetallic Structure. Sensors 2023, 23, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.; Diehl, M.; Reuter, J. Predictive Temperature Control of an Industrial Heating Process. IFAC-Pap. 2024, 58, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, A.; Lazar, C. Model-Free Temperature Control of Heat Treatment Process. Energies 2024, 17, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A. Emerging Trends in Thermo-Optic and Electro-Optic Materials for Tunable Photonic Devices. Materials 2025, 18, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larciprete, M.C.; Centini, M.; Paoloni, S.; Fratoddi, I.; Dereshgi, S.A.; Tang, K.; Wu, J.; Aydin, K. Adaptive Tuning of Infrared Emission Using VO2 Thin Films. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, E.; Ristau, D. Photothermal Measurements on Optical Thin Films. Appl. Opt. 1995, 34, 7239–7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashed, A.N.Z.; Zaky, M.M.; Mohamed, A.E.-N.A.; Ahmed, H.E.H.; Elsaket, A.I. Applications of an Extremely Sensitive Temperature Sensor Based on Surface Plasmon Photonic Crystal Fiber in Nuclear Reactors. J. Opt. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler Gates, J.; Tsvetkov, P.V. Testing of Fiber Optic Based Sensors for Advanced Reactors in the Texas A&M University TRIGA Reactor. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2024, 196, 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Qiang, D.; Lin, J.; Jia, S.; Xu, L.; Ye, E.; Jiang, W.; Li, H.; Sun, D. Polymer-Derived Ceramics Phosphor Thin-Film Sensors for Extreme Environment. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 38990–39001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; He, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Hai, Z.; Sun, D. La(Ca)CrO3-Filled SiCN Precursor Thin Film Temperature Sensor Capable to Measure up to 1100 °C High Temperature. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslanidis, E.; Skotadis, E.; Moutoulas, E.; Tsoukalas, D. Thin Film Protected Flexible Nanoparticle Strain Sensors: Experiments and Modeling. Sensors 2020, 20, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciak, E. Low-Coherence Interferometric Fiber Optic Sensor for Humidity Monitoring Based on Nafion® Thin Film. Sensors 2019, 19, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnik, K.; Martychowiec, A.; Kwietniewski, N.; Musolf, P.; Niedziółka-Jönsson, J.; Koba, M.; Śmietana, M. Thin-Film-Based Optical Fiber Interferometric Sensor on the Fiber Tip for Endovascular Surgical Procedures. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 72, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Gerhard, E. A Simple Strain Sensor Using a Thin Film as a Low-Finesse Fiber-Optic Fabry–Perot Interferometer. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2001, 88, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O. Revolutionizing Infrastructure: The Future of Fiber Optic Sensing in Structural Health Monitoring. Available online: https://www.azooptics.com/Article.aspx?ArticleID=2572 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Butt, M.A. A Comprehensive Exploration of Contemporary Photonic Devices in Space Exploration: A Review. Photonics 2024, 11, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, T.; Zalar, P.; Kaltenbrunner, M.; Jinno, H.; Matsuhisa, N.; Kitanosako, H.; Tachibana, Y.; Yukita, W.; Koizumi, M.; Someya, T. Ultraflexible Organic Photonic Skin. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhialini, C.A.; Martins, L.G.P.; Fan, S.; Bisogni, V.; Yasunami, T.; Musashi, M.; Kawasaki, M.; Uchida, M.; Comin, R.; Pelliciari, J. Strain-Modulated Anisotropic Electronic Structure in Superconducting RuO2 Films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2022, 6, 084802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.J.; Baek, S.-H.; Chopdekar, R.V.; Mehta, V.V.; Jang, H.-W.; Eom, C.-B.; Suzuki, Y. Metallicity in LaTiO3 Thin Films Induced by Lattice Deformation. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Verma, K.; singh, D. sethi Defect Engineering in Nanomaterials: Impact, Challenges, and Applications. Smart Mater. Manuf. 2024, 2, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, U.; Younis, M.I. Chemical Gas Sensors: Recent Developments, Challenges, and the Potential of Machine Learning—A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas Alam, M.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, S.; Mohammad Junaid, P.; Awad, M. VOC Detection with Zinc Oxide Gas Sensors: A Review of Fabrication, Performance, and Emerging Applications. Electroanalysis 2025, 37, e202400246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, M.; Kapuścik, P.; Weichbrodt, W.; Domaradzki, J.; Mazur, P.; Kot, M.; Flege, J.I. WO3 Thin-Film Optical Gas Sensors Based on Gasochromic Effect towards Low Hydrogen Concentrations. Materials 2023, 16, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Application of Graphene as Sensors: A Review. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2608, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Qin, C.; Li, Y.; Tan, T.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Yao, B.; Rao, Y. Graphene-Fiber Biochemical Sensors: Principles, Implementations, and Advances. Photonic Sens. 2021, 11, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bado, M.F.; Casas, J.R. A Review of Recent Distributed Optical Fiber Sensors Applications for Civil Engineering Structural Health Monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, A.; Meher, S.R.; Alex, Z.C. Metal Oxide Thin Films Coated Evanescent Wave Based Fiber Optic VOC Sensor. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2022, 338, 113459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.-Y.; Dhital, D.; Lee, J.-R.; Park, G.; Kwon, I.-B. Design of Multiplexed Fiber Optic Chemical Sensing System Using Clad-Removable Optical Fibers. Opt. Laser Technol. 2012, 44, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motala, M.; Beagle, L.K.; Lynch, J.; Moore, D.C.; Stevenson, P.R.; Benton, A.; Tran, L.D.; Baldwin, L.A.; Austin, D.; Muratore, C.; et al. Selective Vapor Sensors with Thin-Film MoS2-Coated Optical Fibers. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2022, 40, 032202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Duan, P.; Kumar, T.; Venkataraman, A.; Papadopoulos, C. Thin Film Gas Sensors Based on Planetary Ball-Milled Zinc Oxide Nanoinks: Effect of Milling Parameters on Sensing Performance. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ahmad, I.; Geun, I.; Hamza, S.A.; Ijaz, U.; Jang, Y.; Koo, J.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, H.-D. A Comprehensive Review of Advanced Sensor Technologies for Fire Detection with a Focus on Gasistor-Based Sensors. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Piramidowicz, R. Integrated Photonic Sensors for the Detection of Toxic Gasses—A Review. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotchenkov, G.; Brynzari, V.; Dmitriev, S. SnO2 Thin Film Gas Sensors for Fire-Alarm Systems. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1999, 54, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacci, G.; Goyvaerts, J.; Zhao, H.; Baumgartner, B.; Lendl, B.; Baets, R. Ultra-Sensitive Refractive Index Gas Sensor with Functionalized Silicon Nitride Photonic Circuits. APL Photonics 2020, 5, 081301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, F.; Han, H.; Zhang, P. A Review of SiC Sensor Applications in High-Temperature and Radiation Extreme Environments. Sensors 2024, 24, 7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwal, P.; Rani, S.; Sihag, S.; Singh, P.; Bulla, M.; Jatrana, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V. Fabrication of NiO Based Thin Film for High-Performance NO2 Gas Sensors at Low Concentrations. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2024, 685, 416023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

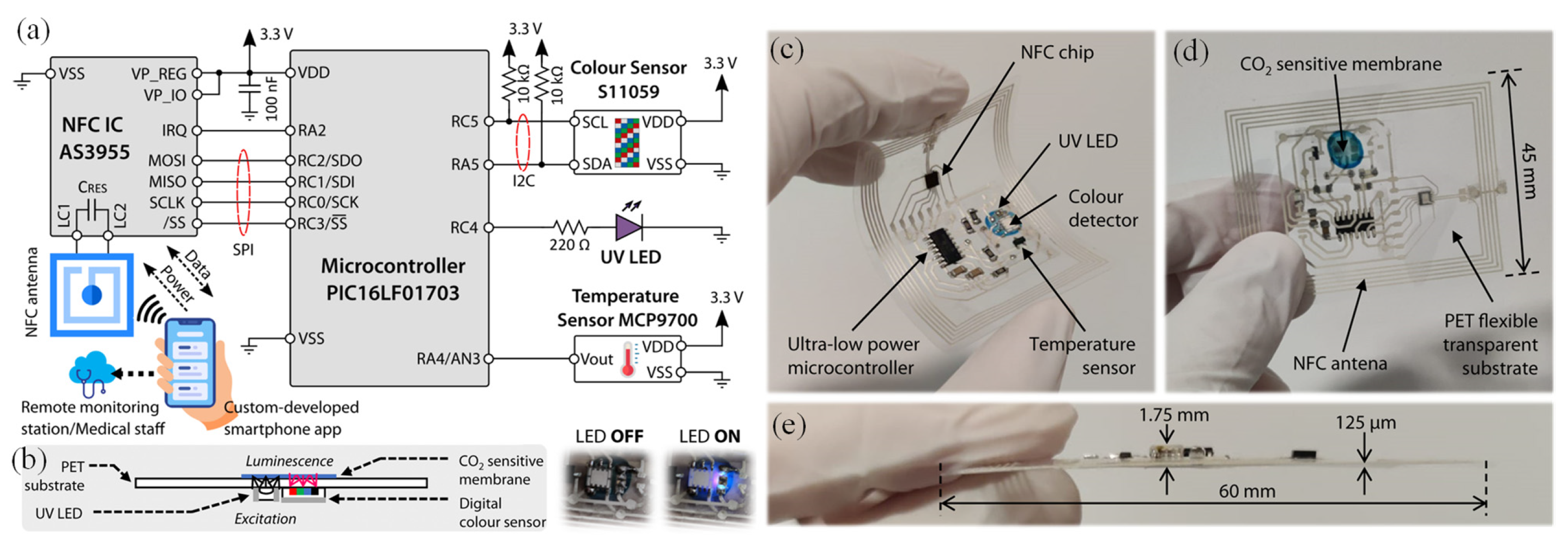

- Escobedo, P.; Fernández-Ramos, M.D.; López-Ruiz, N.; Moyano-Rodríguez, O.; Martínez-Olmos, A.; Pérez de Vargas-Sansalvador, I.M.; Carvajal, M.A.; Capitán-Vallvey, L.F.; Palma, A.J. Smart Facemask for Wireless CO2 Monitoring. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, P.P.; Gregory, O.J. Free-Standing, Thin-Film Sensors for the Trace Detection of Explosives. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-García, G.; Wang, L.; Yetisen, A.K.; Morales-Narváez, E. Photonic Solutions for Challenges in Sensing. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25415–25420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

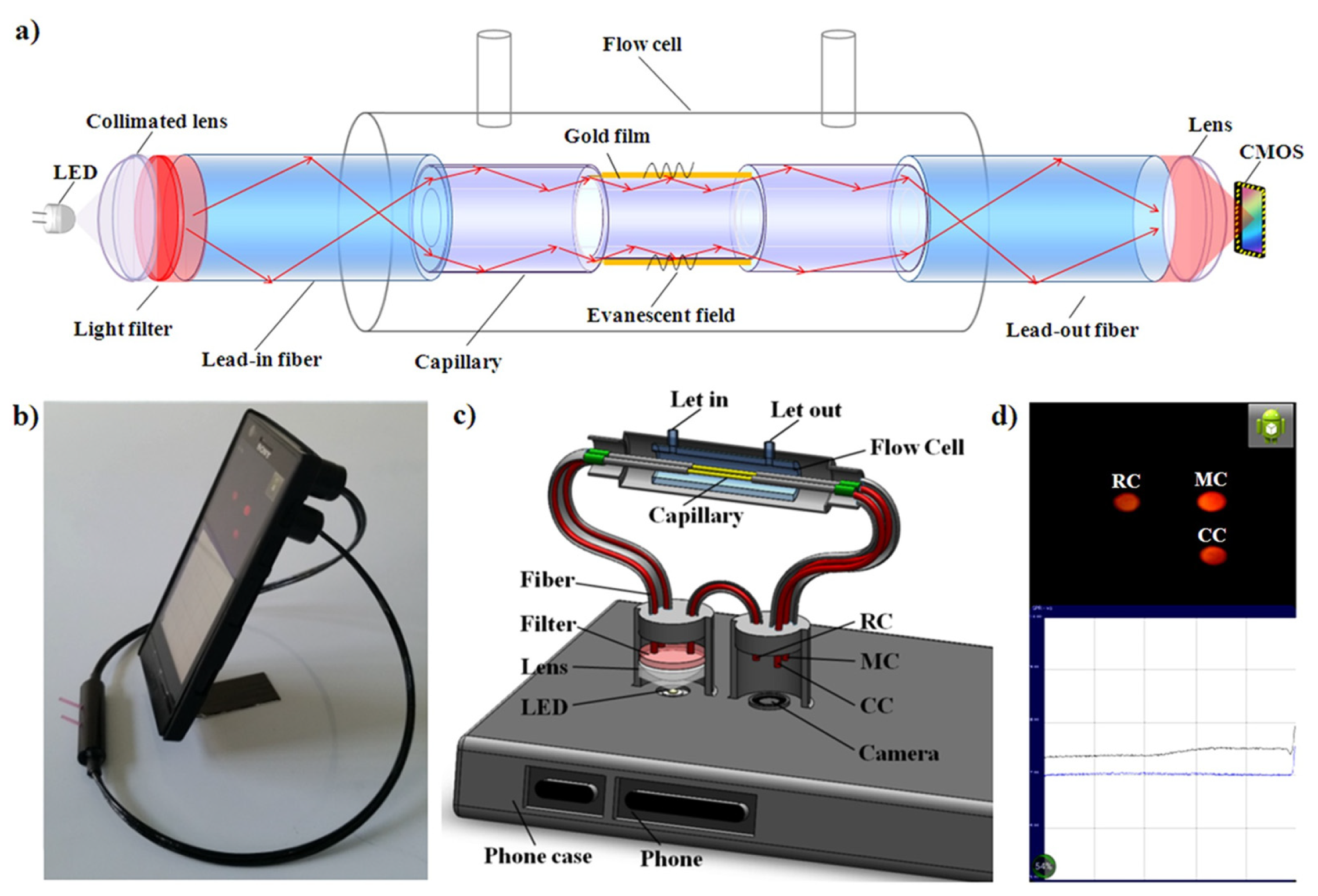

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Cheng, F.; Wang, H.; Peng, W. Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor Based on Smart Phone Platforms. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Peng, D.; Bai, X.; Liu, S.; Luo, L. A Review of Optical Fiber Sensing Technology Based on Thin Film and Fabry–Perot Cavity. Coatings 2023, 13, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chaudhary, B.; Upadhyay, A.; Sharma, D.; Ayyanar, N.; Taya, S.A. A Review on Various Sensing Prospects of SPR Based Photonic Crystal Fibers. Photonics Nanostructures-Fundam. Appl. 2023, 54, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Dai, J. Review on Optical Fiber Sensors with Sensitive Thin Films. Photonic Sens. 2012, 2, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Kornblum, E.; Biehl, S.; Paetsch, N.; Bräuer, G. Investigation of Application-Specific Thin Film Sensor Systems with Wireless Data Transmission System. Proceedings 2018, 2, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Cattley, R.; Gu, F.; Ball, A.D. Energy Harvesting Technologies for Achieving Self-Powered Wireless Sensor Networks in Machine Condition Monitoring: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.N.; Chen, H.P.; Chiu, P.K.; Cho, W.H.; Lin, Y.W.; Chen, F.Z.; Tsai, D.P. Design and Fabrication of Optical Thin Films for Remote Sensing Instruments. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2010, 28, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Xu, X.; Zi, J.; Wang, J.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, M. A High-Performance Thin-Film Sensor in 6G for Remote Sensing of the Sea Surface. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tian, B.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Shi, P.; Lin, Q.; et al. A Thin-Film Temperature Sensor Based on a Flexible Electrode and Substrate. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2021, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabé, S.; Tekin, T.; Sirbu, B.; Charbonnier, J.; Grosse, P.; Seyfried, M. Packaging and Test of Photonic Integrated Circuits (PICs). In Integrated Nanophotonics; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–52. ISBN 978-3-527-83303-0. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, L.P.; Povinelli, M.L.; Ramirez, J.C.; Guimarães, P.S.S.; Neto, O.P.V. Photonic Crystal Integrated Logic Gates and Circuits. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 1976–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Słowikowski, M.; Drecka, D.; Jarosik, M.; Piramidowicz, R. Experimental Characterization of a Silicon Nitride Asymmetric Loop-Terminated Mach-Zehnder Interferometer with a Refractive Index-Engineered Sensing Arm. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muellner, P.; Bruck, R.; Baus, M.; Karl, M.; Wahlbrink, T.; Hainberger, R. On-Chip Multiplexing Concept for Silicon Photonic MZI Biosensor Array. Proc. SPIE-Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2012, 8431, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taharat, A.; Kabir, M.A.; Keats, A.I.; Rakib, A.K.M.; Sagor, R.H. Advancing Optomechanical Sensing: Novel CMOS-Compatible Plasmonic Pressure Sensor with Silicon-Insulator-Silicon Waveguide Configuration. Opt. Commun. 2025, 578, 131495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augel, L.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Bechler, S.; Körner, R.; Schulze, J.; Uchida, H.; Fischer, I.A. Integrated Collinear Refractive Index Sensor with Ge PIN Photodiodes. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 4586–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Dutta, A.; Kinsey, N.; Kildishev, A.V.; Shalaev, V.M.; Boltasseva, A. On-Chip Hybrid Photonic-Plasmonic Waveguides with Ultrathin Titanium Nitride Films. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 4423–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pei, W.; Lu, Y.; Li, W.; Huang, A.; Jiao, H.; Feng, D.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, L. Thin-Film Lithium Niobate Multi-Channel Multifunctional Photonic Integrated Chip for Interferometric Optical Gyroscope. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 30669–30685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrbanek, J.D.; Fralick, G.C. Thin Film Physical Sensors for High Temperature Applications. In Proceedings of the NASA-GE Instrumentation Mini Workshop, Cleveland, OH, USA, 22 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nadafan, M.; Shahram, S.; Zamir Anvari, J.; Khashehchi, M. Thermal and Optical Characterization of a Resistance-Temperature Detector Based on Platinum Thin Film: Design and Fabrication. Optik 2023, 290, 171349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, H.; Guler, U.; Kudyshev, Z.; Kildishev, A.V.; Shalaev, V.M.; Boltasseva, A. Temperature-Dependent Optical Properties of Plasmonic Titanium Nitride Thin Films. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, C.-L.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Wang, C.-C.; Lin, S.-C. Temperature-Dependent Residual Stresses and Thermal Expansion Coefficient of VO2 Thin Films. Inventions 2024, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guk, E.; Ranaweera, M.; Venkatesan, V.; Kim, J.-S. Performance and Durability of Thin Film Thermocouple Array on a Porous Electrode. Sensors 2016, 16, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhao, H.; Fang, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, B.; Zhao, L.; Li, T.; et al. Pt Thin-Film Resistance Thermo Detectors with Stable Interfaces for Potential Integration in SiC High-Temperature Pressure Sensors. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas-Gil, A.; Elam, J.W. Modeling Scale-up of Particle Coating by Atomic Layer Deposition. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2024, 43, 012404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, B.A. Molecular Beam Epitaxy-Fundamentals and Current Status. In Contemporary Physics; SSMATERIALS, Volume 7; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, S.; Hajakbari, F.; Hojabri, A. Effect of Silver Thickness on Structural, Optical and Morphological Properties of Nanocrystalline Ag/NiO Thin Films. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 2018, 12, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.J.M.; Lin, W.; Taima, T.; Umezu, S.; Shahiduzzaman, M. Unleashing the Potential of Industry Viable Roll-to-Roll Compatible Technologies for Perovskite Solar Cells: Challenges and Prospects. Mater. Today 2024, 78, 112–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulowski, W.; Knura, R.; Socha, R.P.; Basiura, M.; Skibińska, K.; Wojnicki, M. Thin Film Semiconductor Metal Oxide Oxygen Sensors: Limitations, Challenges, and Future Progress. Electronics 2024, 13, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov, S.M.; Seifner, R.; Klimant, I. A Novel Planar Optical Sensor for Simultaneous Monitoring of Oxygen, Carbon Dioxide, pH and Temperature. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 400, 2463–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanth, S.; Choudhury, S.; Kumar, S.; Rao, R.; Debnath, A.K.; Betty, C.A. Reliable NO2 Sensing and Alert System Based on Pd-PdO Thin Film with Sub Ppm Level Detection at Room Temperature. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 403, 135145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.J.; Weiss, S.M. Reducing Detection Limits of Porous Silicon Thin Film Optical Sensors Using Signal Processing. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Biological Detection: From Nanosensors to Systems XIII, San Francisco, CA, USA, 16 March 2021; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; Volume 11662, pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Röbisch, V.; Salzer, S.; Urs, N.O.; Reermann, J.; Yarar, E.; Piorra, A.; Kirchhof, C.; Lage, E.; Höft, M.; Schmidt, G.U.; et al. Pushing the Detection Limit of Thin Film Magnetoelectric Heterostructures. J. Mater. Res. 2017, 32, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, L.; Mariello, M.; Proctor, C.M. High Dynamic Range Thin-Film Resistive Flow Sensors for Monitoring Diverse Biofluids. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e10372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, D.; Scherr, H.; Lueder, E.H. Increasing the Dynamic Range of an Array of Light Sensors Using a New Thin-Film Circuit. In Proceedings of the Solid State Sensor Arrays and CCD Cameras, San Jose, CA, USA, 25 March 1996; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA; Volume 2654, pp. 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.; Shi, Y.; Du, Q.; Feng, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, K.; Xue, D. Ceramic Phosphors for Laser-Driven Lighting. Rev. Mater. Res. 2025, 1, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, S.M.; Khani, S.; Örtegren, J. Ultra-Compact Multifunctional Surface Plasmon Device with Tailored Optical Responses. Results Phys. 2024, 61, 107783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.T.; Choi, H.; Shin, E.; Park, S.; Kim, I.G. Graphene-Based Optical Waveguide Tactile Sensor for Dynamic Response. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabbas, S.H.; Ashworth, D.C.; Bezzaa, B.; Momin, S.A.; Narayanaswamy, R. Factors Affectig the Response Time of an Optical-Fibre Reflectance pH Sensor. Sens. Actuators Phys. 1995, 51, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, G.; Guadagno, L.; Raimondo, M.; Santonicola, M.G.; Toto, E.; Vecchio Ciprioti, S. A Comprehensive Review on the Thermal Stability Assessment of Polymers and Composites for Aeronautics and Space Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, R.; Zou, F.; Li, D.; Yao, Y. A High-Thermal-Stability, Fully Spray Coated Multilayer Thin-Film Graphene/Polyamide-Imide Nanocomposite Strain Sensor for Acquiring High-Frequency Ultrasonic Waves. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 227, 109628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Martín, A.; Jost, N.; Hernández, J.J.; Domínguez, C.; Vallerotto, G.; Askins, S.; Antón, I.; Rodríguez, I. Roll-to-Roll Nanoimprint Lithography of High Efficiency Fresnel Lenses for Micro-Concentrator Photovoltaics. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 34135–34149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.H.; Lee, G.J.; Yun, J.H.; Song, Y.M. NFC-Based Wearable Optoelectronics Working with Smartphone Application for Untact Healthcare. Sensors 2021, 21, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, D.; Lee, C. Technology Landscape Review of In-Sensor Photonic Intelligence: From Optical Sensors to Smart Devices. AI Sens. 2025, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venketeswaran, A.; Lalam, N.; Wuenschell, J.; Ohodnicki, P.R., Jr.; Badar, M.; Chen, K.P.; Lu, P.; Duan, Y.; Chorpening, B.; Buric, M. Recent Advances in Machine Learning for Fiber Optic Sensor Applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.D.; Chang, D. Artificial Intelligence in Point-of-Care Biosensing: Challenges and Opportunities. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.-D.; Ohodnicki, P.R.; Wuenschell, J.K.; Lalam, N.; Sarcinelli, E.; Buric, M.P.; Wright, R. Multiparameter Optical Fiber Sensing for Energy Infrastructure through Nanoscale Light–Matter Interactions: From Hardware to Software, Science to Commercial Opportunities. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 120902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arockiyadoss, M.A.; Yao, C.-K.; Liu, P.-C.; Kumar, P.; Nagi, S.K.; Dehnaw, A.M.; Peng, P.-C. Spectral Demodulation of Mixed-Linewidth FBG Sensor Networks Using Cloud-Based Deep Learning for Land Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, L.E.; Kühl, S.; Dochhan, A.; Pachnicke, S. Experimental Investigation of Machine-Learning-Based Soft-Failure Management Using the Optical Spectrum. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2024, 16, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker Tian, S.I.; Ren, Z.; Venkataraj, S.; Cheng, Y.; Bash, D.; Oviedo, F.; Senthilnath, J.; Chellappan, V.; Lim, Y.-F.; Aberle, A.G.; et al. Tackling Data Scarcity with Transfer Learning: A Case Study of Thickness Characterization from Optical Spectra of Perovskite Thin Films. Digit. Discov. 2023, 2, 1334–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Ali, Z.; Dudley, S.; Saleem, K.; Uneeb, M.; Christofides, N. A Multi-Stage Review Framework for AI-Driven Predictive Maintenance and Fault Diagnosis in Photovoltaic Systems. Appl. Energy 2025, 393, 126108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.; Park, H.-C.; Kang, B. Edge Intelligence: A Review of Deep Neural Network Inference in Resource-Limited Environments. Electronics 2025, 14, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N.; Butt, M.A. A Review of Photonic Sensors Based on Ring Resonator Structures: Three Widely Used Platforms and Implications of Sensing Applications. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkeye, M.M.; Taschuk, M.T.; Brett, M.J. Introduction: Glancing Angle Deposition Technology. In Glancing Angle Deposition of Thin Films: Engineering the Nanoscale; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-1-118-84732-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pula, P.; Leniart, A.A.; Krol, J.; Gorzkowski, M.T.; Suster, M.C.; Wrobel, P.; Lewera, A.; Majewski, P.W. Block Copolymer-Templated, Single-Step Synthesis of Transition Metal Oxide Nanostructures for Sensing Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 57970–57980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ma, D.; Li, H.; Cui, G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z. Review of Industrialization Development of Nanoimprint Lithography Technology. Chips 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Abidian, M.R.; Ahn, J.-H.; Akinwande, D.; Andrews, A.M.; Antonietti, M.; Bao, Z.; Berggren, M.; Berkey, C.A.; Bettinger, C.J.; et al. Technology Roadmap for Flexible Sensors. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 5211–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Said, L.; Ayadi, B.; Alharbi, S.; Dammak, F. Recent Advances in Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Current Developments and Future Directions. Machines 2025, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, C.; Tao, J.; Tang, H.; Wang, Z.; Song, J. A Kirigami-Based Reconfigurable Metasurface for Selective Electromagnetic Transmission Modulation. Npj Flex. Electron. 2024, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Rho, Y.; Pham, K.; McCormick, B.; Blankenship, B.W.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Gilbert, S.M.; Crommie, M.F.; Wang, F.; et al. Kirigami Engineering of Suspended Graphene Transducers. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 5301–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Visagie, I.; Chen, Y.; Abbel, R.; Parker, K. NFC-Enabled Dual-Channel Flexible Printed Sensor Tag. Sensors 2023, 23, 6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Han, G.D.; Choi, H.J.; Prinz, F.B.; Shim, J.H. Evaluation of Atomic Layer Deposited Alumina as a Protective Layer for Domestic Silver Articles: Anti-Corrosion Test in Artificial Sweat. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 441, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, D.; López, A.; DasMahapatra, P.; Capmany, J. Multipurpose Self-Configuration of Programmable Photonic Circuits. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiuftiakov, N.Y.; Kalinichev, A.V.; Gryazev, I.P.; Peshkova, M.A. Ion-Selective Optical Sensors with Internal Reference: On the Quest for Prolonged Functionality and Calibration-Free Measurements. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 443, 138231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Golovastikov, N.V.; Khonina, S.N. The Optic Brain: Foundations, Frontiers, and the Future of Photonic Artificial Intelligence. Mater. Today Phys. 2025, 58, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ren, G.; Feleppa, T.; Liu, X.; Boes, A.; Mitchell, A.; Lowery, A.J. Self-Calibrating Programmable Photonic Integrated Circuits. Nat. Photonics 2022, 16, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmaraju, K.; Logan, D.F.; Zhu, X.; Ackert, J.J.; Knights, A.P.; Bergman, K. Integrated Thermal Stabilization of a Microring Modulator. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 14342–14350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonyár, A.; Kovács, R. Towards Digital Twins of Plasmonic Sensors: Constructing the Complex Numerical Model of a Plasmonic Sensor Based on Hexagonally Arranged Gold Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiberg, M. Toward Digital Twins by One-Dimensional Simulation of Thin-Film Solar Cells: Cu (In, Ga) Se2 as an Example. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2024, 21, 034051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Sun, H.; Tang, Y.; Wei, J.; Guo, J. Self-Powered Photonic Sensor Using Cholesteric Liquid Crystal Elastomer-Based Sandwiched Architecture with Mechanochromism and Triboelectric Response. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 46226–46237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liang, B.; Fang, L.; Ma, G.; Yang, G.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, S.; Ye, X. Antifouling Zwitterionic Coating via Electrochemically Mediated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization on Enzyme-Based Glucose Sensors for Long-Time Stability in 37 °C Serum. Langmuir 2016, 32, 11763–11770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flexible Piezoelectric Materials and Strain Sensors for Wearable Electronics and Artificial Intelligence Applications. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 16436–16466. [CrossRef]

| Deposition Technique | Working Principle | Thickness Control/Precision | Material Compatibility | Advantages | Limitations | Industrial Relevance/Industrial Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetron Sputtering (Physical Vapor Deposition, PVD) [76,77] | Ejection of target atoms by plasma ions, deposition onto the substrate | nm–µm range, moderate precision | Oxides (ZnO, TiO2, SnO2, WO3), metals (Au, Ag, Pt) | Dense, uniform films; good adhesion; scalable to large areas; robust coatings | Equipment cost; slower deposition for thick films; requires vacuum | Industrial coatings for temperature/strain sensors; tool-integrated thin-film sensors |

| Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) [78,79] | Sequential self-limiting surface reactions, cycle-by-cycle growth | Å-level (0.1–0.2 nm/cycle) | Oxides (Al2O3, TiO2, HfO2), nitrides, hybrid nanolaminates | Ultra-precise thickness; conformal coverage on 3D/porous structures; defect control | Low throughput; expensive precursors; not yet cost-effective at large scales | Nanoscale resonators, waveguides, flexible strain sensors with humidity protection |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD, incl. PECVD) [80,81] | Gas-phase precursors react/decompose on heated substrate | nm–µm; tunable | 2D materials (graphene, MoS2), perovskites, high-purity oxides | High-quality crystalline films; scalable; suitable for electronics integration | Requires high T (≥500 °C); precursor hazards; uniformity issues on large substrates | Growth of graphene/MoS2 for chemical sensing; CMOS-compatible integration |

| Sol–Gel Processing [69,82] | Hydrolysis/condensation of metal alkoxides → gel → thin film via spin/dip coating | 10 s–100 s of nm | SiO2, TiO2, ZnO, hybrid organic–inorganic | Low cost; tunable porosity; easy doping; large-area deposition | Shrinkage/cracking during annealing; lower density vs. PVD/ALD | Porous oxide films for chemical sensing (gas/VOC detection) |

| Inkjet/Aerosol Jet/Screen Printing (Additive Manufacturing) [83,84,85] | Direct deposition of functional inks in patterned form | µm-scale thickness, patternable | Polymers, hybrid films, nanomaterials (graphene inks, oxides) | Maskless, scalable, flexible substrates (PET, PDMS); Industry 4.0 friendly | Lower resolution vs. lithography; ink formulation critical; surface roughness | Flexible/wearable photonic sensors, disposable chemical detectors |

| Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) [86,87,88] | Evaporation of elemental beams under UHV; epitaxial growth | Sub-nm precision | III–V semiconductors, perovskites | High-purity, defect-free films; precise bandgap tuning | Very costly; ultra-slow; limited scalability | Prototype quantum/photonic structures, research-scale TFPS (thin film photonic sensors) |

| Application Domain | Representative Thin-Film Materials | Optical Principle Used | Key Performance Metric (Representative Values) | Industrial Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Monitoring [116,120] | VO2, SiO2, TiO2, Y2O3:Eu phosphor | Thermo-optic effect, phase transition, IR emission | Sensitivity: ~10–200 pm °C−1; operating range: −50 to >500 °C; response time: <1 s to several seconds; long-term drift: <1% h−1 | Turbine blade monitoring, reactor temperature mapping |

| Strain/Stress Monitoring [125] | Pt nanoparticle films, Al2O3-coated sensors, ZnO | Fabry–Pérot interference, thin-film interferometry | ~1–10 µε; gauge factor (hybrid/optical): ~10–103; dynamic range: up to several mε; fatigue endurance: >106 cycles | Aerospace wing/fuselage stress detection |

| Chemical Leakage Detection [134] | SnO2, ZnO, WO3, MoS2, Graphene | Refractive index change, absorption, gasochromic effect | ppb–ppm range; response/recovery time: seconds–minutes; selectivity: material-dependent; stability: hours–days without recalibration | Pipeline VOC detection, refinery gas monitoring |

| Safety/Hazard Monitoring [144,149] | SnO2, SiC, hybrid oxide films | Plasmonic sensing, gasochromic, photonic crystal bandgap shift | ppb–ppm; alarm time: <10 s–minutes; operating humidity: 10%–90% RH; environmental robustness: moderate–high (platform dependent) | Fire alarms, explosive detection in transport hubs |

| Performance Metric | State-of-the-Art Values | Failure/Degradation Mechanisms | Technical Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity/Limit of Detection (LoD) [180,181,182] | Gas sensors: ~100 ppb (SnO2, MoS2, graphene); Strain: gauge factor (GF) 5–20; Temperature: ±1–2 °C at >1000 °C | Cross-sensitivity (e.g., T–strain coupling), spectral drift, low SNR in noisy environments | Multilayer heterostructures combining plasmonic and oxide films to enhance field confinement and selectivity, bound states in the continuum resonators to increase quality factor and suppress noise, machine learning assisted spectral deconvolution to decouple overlapping temperature, strain, and chemical responses |

| Dynamic Range/Operating Range [183,184,185] | Thermal: up to 1200 °C (phosphor films, ceramics); Strain: 103–104 µε; Gas conc.: 10−4–102 ppm | Nonlinear response at high perturbations, saturation of adsorption sites, hysteresis | Adaptive calibration models to correct nonlinear behavior under large perturbations, hierarchical film architectures with nanoporous oxides and dense overlayers to delay saturation of active sites, integrated microheaters to extend operational range through controlled thermal activation |

| Response/Recovery Time [186,187,188] | Gas sensors: 10–30 s (ZnO, WO3); Optical strain: sub-ms; Temperature: ms–s depending on film thickness | Surface reaction kinetics limited at RT, slow desorption, thermal lag in bulk substrates | Nanostructured one-dimensional and two-dimensional films to increase surface-to-volume ratio, catalytic nanoparticle doping to lower activation energy for adsorption and desorption, ultrathin conformal coatings deposited by ALD to minimize diffusion length and thermal inertia, microheater integration to accelerate recovery |

| Long-Term Stability/Drift [35,189,190] | Stable for months in lab; <10% drift over 106 cycles (strain); but severe drift under corrosive or humid atmospheres | Oxygen vacancy migration, photobleaching, film delamination, crack propagation under cyclic stress | Encapsulation using ALD Al2O3 or Parylene-C to suppress moisture ingress and oxygen diffusion, hydrophobic overcoats to reduce humidity-induced drift, stress-relief buffer layers to mitigate crack propagation, in situ self-calibration using reference resonators to correct long-term drift |

| Fabrication Scalability & Reproducibility [76,82,174,191] | ALD: Å-level precision, but <10 cm2 throughput; Inkjet: 104 cm2/day but µm resolution; Roll-to-roll sputtering: 102 m2 scale | Batch-to-batch variability (thickness, crystallinity), ink instability, substrate-induced strain | Hybrid deposition strategies combining ALD seeding with printing to balance precision and scalability, plasma-assisted roll-to-roll sputtering to improve film uniformity, inline ellipsometry with AI-based quality control to detect deviations during fabrication |

| Integration/Packaging Robustness [107,160] | Fiber-integrated sensors: km-scale networks; On-chip: >20 components per PIC; Flexible e-skin: <5 µm thickness | Fiber–chip coupling loss, vibration-induced delamination, packaging thermal mismatch | CMOS-compatible integration to ensure process uniformity, ruggedized fiber arrays to reduce coupling loss, compliant encapsulation layers to absorb vibration and thermal stress, serpentine or kirigami mechanical designs to enhance flexibility and fatigue resistance |

| IoT/Cyber-Physical Readiness [9,192] | NFC-enabled flexible tags: power < 5 mW; Distributed fiber-optic networks with OTDR; Edge-AI latency < 10 ms | Power autonomy, cybersecurity risks, limited on-chip computing | Energy harvesting from vibration, thermal, or solar sources to enable autonomous operation, neuromorphic or edge processors to reduce latency and power consumption, physically unclonable functions and secure firmware updates to ensure data integrity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Butt, M.A. Thin-Film Sensors for Industry 4.0: Photonic, Functional, and Hybrid Photonic-Functional Approaches to Industrial Monitoring. Coatings 2026, 16, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010093

Butt MA. Thin-Film Sensors for Industry 4.0: Photonic, Functional, and Hybrid Photonic-Functional Approaches to Industrial Monitoring. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleButt, Muhammad A. 2026. "Thin-Film Sensors for Industry 4.0: Photonic, Functional, and Hybrid Photonic-Functional Approaches to Industrial Monitoring" Coatings 16, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010093

APA StyleButt, M. A. (2026). Thin-Film Sensors for Industry 4.0: Photonic, Functional, and Hybrid Photonic-Functional Approaches to Industrial Monitoring. Coatings, 16(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010093