1. Introduction

The rapid growth of wearable and flexible electronics has stimulated strong interest in the development of conductive materials that combine high performance, user comfort, and environmental sustainability [

1,

2,

3]. In particular, the development of sustainable printed electronics has become a key research direction, aiming to replace petroleum-based polymers and hazardous solvents with bio-based matrices, waterborne formulations, and low-impact processing routes [

4]. Mechanically flexible conductors are considered essential to obtain e-textiles devices that can maintain electrical functionality under repeated mechanical deformation [

5,

6]. Although metal fillers are traditionally used for their excellent electrical conductivity, they often pose environmental and economic sustainability issues [

7]. Among the different approaches, graphene has emerged as the material of choice thanks to its exceptional electrical conductivity, mechanical robustness, and chemical stability. Applications range from washable conductive coatings to electroactive devices such as sensors and electrochromic elements [

8]. Recent work on textile-integrated sensing platforms has demonstrated the essential role of conductive coatings that are durable, washable, and able to resist deformation for the real-time monitoring functions of wearable systems. This further emphasizes the need for sustainable and long-lasting conductive materials [

9].

A wide range of synthetic substrates, such as polyester textile [

10] and natural textiles, for example, cotton [

11] and paper [

12], have been explored for wearable electronics, owing to their availability, durability, and ease of processing. However, their hydrophobicity often hinders uniform coating adhesion, requiring optimized binders or surface modification strategies. For example, the cotton fabrics functionalized with nanocarbons can provide cost-effective conductive platforms, though with limitations in terms of mechanical resistance and wash resistance [

13]; more recently, it was shown that simple graphite treatments enable the realization of capacitive cotton-based textiles, opening new opportunities for sustainable tactile sensors [

4]. Other flexible substrates, including paper and polymer films (e.g., PET, TPU foils), have also been proposed for printed electronics, which are commonly used for sensors, antennas, and energy storage devices [

14].

Despite these advances, three major challenges remain to be addressed: long-term washability, which is crucial for real deployment in wearable devices [

15]; the need for organic-free solvents and bio-based polymers [

16]; and obtaining resistivity values within 10

4 Ohm/□, for which a material can be classified as conductive. In fact, the term ‘conductive range’ refers to the level of electrical conductivity required for effective charge transport in functional materials. According to ESD Association standards, this level is typically above ~1 × 10

−4 S/cm, which distinguishes truly conductive materials from dissipative ones (which lie between ~1 × 10

−11 and ~1 × 10

−4 S/cm). This illustrates the level of performance needed for coatings and devices to operate reliably [

17]. In this context, thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPUs) are widely used due to their combination of flexibility, adhesion to textiles, and wash resistance. The use of waterborne TPU dispersions combines environmental advantages (low VOC, moderate processing temperatures, compatibility with aqueous inks/primers) with key functional properties for e-textiles: adhesion to fibrous substrates, flexibility, and wash resistance. Waterborne TPU formulations with crosslinkers have demonstrated a significant enhancement of electrical durability during laundering (up to ~120 cycles without loss of conductivity in a few-layer graphene-based printed pathway) thanks to the formation of a denser and more continuous network [

15]. Even in green-functionalized textiles, aqueous polyurethane binders have been employed to tune transiency and wash resistance, confirming that water-based polyurethane chemistry has been shown to improve wash resistance while maintaining fully waterborne processing [

16]. In addition, TPU offers a hard–soft microphase structure that can be adjusted to optimize adhesion on substrates and filler integration: the hard–soft segment ratio directly influences percolation continuity and dielectric response of the composite. Under humid conditions and during laundering, water absorption may induce softening or hardening phenomena in TPU, underlining the importance of tailored architectures and crosslinking [

18,

19].

Studies on TPU-based nano-carbon composites have shown that polymer microstructure affects filler dispersion, dielectric behavior and percolation network formation [

18,

20]. In particular, few-layer graphene (FLG), due to its remarkable electrical conductivity, mechanical flexibility, and high surface area, has been widely explored for applications in coatings, sensors, and energy storage devices. Recent experimental studies on graphene-coated fabrics have reported significant increases in electrical conductivity and tensile performance when graphene nanoplatelets are effectively dispersed and integrated into textile fibers [

21]. Few layers are defined as stacked layers (<10), and these nanosheets, characterized by their thickness, can be stabilized against re-aggregation by non-covalent interactions with diverse solvents, surfactants, polymers, or stacking π–π aromatic molecules [

22]. However, the uniform dispersion of FLG in polymer matrices remains a critical challenge, as it significantly influences the final properties of the composite material. A list of additives are used to provide the FLG dispersion. One of these, to preserve the green approach, is the polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), which is used as a surfactant and stabilizer. PVP is a non-ionic, amphiphilic polymer that adsorbs onto hydrophobic surfaces such as graphene and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) via hydrophobic and π–π interactions. Meanwhile, its polar chains remain solvated in water, ensuring the steric stabilization of dispersed particles [

23]. This makes it an effective dispersant in graphene and CNT-based systems: in aqueous graphene inks, PVP improves wettability and stability, with conductivity enhancements of up to 80% compared to additive-free systems [

24]. These features make PVP an ideal green, non-ionic additive for the formulation of stable, printable, and conductive TPU/PVP/graphene inks.

This work proposes a systematic and sustainable strategy based exclusively on bio-based waterborne formulations. Four different thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) matrices with different structures and hard–soft segments composition were investigated as a polymeric matrix to prepare a composite.

Four TPUs were selected for this study to represent different architectures and polarities in order to cover a broad spectrum of interfacial interactions between the coating and the substrate. Specifically, the following materials were chosen: an aliphatic polycarbonate-based TPU (U6150); an aliphatic polyester TPU (U4190); and two bio-based TPUs with renewable carbon content (reported in brackets)—BIO S03 (59%) and BIO E02 (70%). This selection enables the controlled modulation of interactions with substrates of different natures, ranging from hydrophilic materials, such as cotton and paper, to hydrophobic materials, such as PET fabrics with varying surface energies. It also allows the investigation of how segmental composition and the chemical nature of the soft segment influence the formation and continuity of the graphene percolation network, as well as the electrical stability of the coatings after repeated washing cycles. This approach enables the intrinsic effect of the TPU microstructure to be isolated and understood while keeping the filler and dispersing additive constant [

19,

25].

The filler content of 2.5 wt% FLG was selected based on preliminary tests and by comparing the electrical properties with commercial non-washable ink. According to previous studies on graphene/polyurethane systems, PVP was introduced as a non-ionic amphiphilic stabilizer to promote graphene exfoliation and prevent agglomeration, enabling the formation of homogeneous aqueous dispersions, avoiding organic solvents [

23].

The coatings were deposited using the bar-coating technique, which is easily scalable for industrial use. Five representative substrates, including both hydrophilic materials (e.g., cotton and paper) and hydrophobic materials (three PET textiles with different surface energies), were used to evaluate the influence of substrate polarity on coating adhesion and uniformity.

The water-borne, bio-based comparative approach addresses the current absence of systematic studies correlating the segmental architecture of thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPUs) with the electrical conductivity and washability of coatings applied to different substrates. This study establishes a direct relationship between the microstructure of the TPUs and the performance of the coatings, linking the segmental architecture to water and diiodomethane wettability, surface energy, morphology, filler distribution, and electrical stability during extended washing cycles. The morphology and filler distribution were analyzed by SEM, while FT-IR spectroscopy was used to assess interactions between TPU, PVP, and FLG. Electrical performance and wash durability were evaluated through sheet resistance measurements before and after up to 180 washing cycles, providing a quantitative measure of the coatings’ stability and adhesion. Comprehensive overviews of graphene-enhanced textiles emphasize that enhanced washability is achieved through improved substrate–coating adhesion, uniform coating morphology, and optimized composite design [

21].

The proposed framework provides practical design criteria for developing sustainable, washable, high-performance conductive coatings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Four bio-based TPUs, differing in chemical composition and mechanical properties, were selected (

Table 1). The TPUs were selected to represent a range of chemical architectures and bio-based content: U6150 (polycarbonate-based aliphatic TPU), U4190 (aliphatic polyester TPU), BIO S03 (aliphatic polyester TPU with ~59% bio-based carbon), and BIO E02 (polycarbonate-rich aliphatic TPU with ~70% bio-based carbon).

PVP powder (PVP K30, average Mw ≈ 55,000) was obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). FLG (2–5 layers, lateral size 10–60 μm) was supplied by GrapheneUP (Graphene UP SE, Ltd., Studeněves, Czech Republic) [

26].

2.2. Preparation of TPU-PVP-FLG Dispersions

PVP was added to each formulation by dissolving 0.2 g of PVP into 20 mL of the selected waterborne TPU dispersion, corresponding to a fixed concentration of 2 wt% to promote FLG stabilization. The PVP was dispersed in the aqueous TPU matrix mixtures, stirring at room temperature for 1 h to allow complete dissolution. Subsequently, FLG (2.5 wt% relative to the TPU solid content) was gradually introduced into the TPU/PVP solution under high-shear homogenization (Ultra-Turrax T25, IKA, Königswinter, Germany) at 6500 rpm for 10 min to ensure a uniform dispersion of the graphene sheets.

2.3. Coating Deposition

The TPU-based coatings were deposited onto three types of pre-treated substrates: cotton (260 GML, Beste S.p.A., Prato, PO, Italy), paper, and three different polyester fabrics (Delfi srl, Prato, PO, Italy). In particular, three polyester fabrics were selected, each characterized by distinct hydrophilicity, as evidenced by their water and diiodomethane contact angles. The fabric PET with a 112° water contact angle was named PET 1 (70 GML), the fabric PET with a 97° water contact angle was named PET 2 (195 GML), and the fabric PET with a 29° water contact angle was named PET 3 (195 GML) (

Figure 1). All fabrics were kindly provided by Grado Zero Research Lab (Montelupo Fiorentino, FI, Italy).

The coatings were applied using a bar-coating technique (K Paint Coater Model 202, RK PrintCoat Instruments, Litlington, UK) equipped with a No. 12 wire-wound bar, in a single pass at a constant coating speed of 6 m/min, producing a wet film thickness of approximately 12 µm. The coatings were applied using a 12 µm wire-wound bar in a single pass at a constant coating speed of 10 cm s−1. During bar-coating deposition, the shear field generated at the liquid–film interface can promote a partial in-plane alignment of graphene flakes.

This shear-induced orientation contributes to the formation of lateral conductive pathways, as the nanosheets tend to unfold and arrange more parallel to the substrate, thereby enhancing filler-to-filler contact and facilitating electron transport across the coating [

27].

The coated films were subsequently dried at 90 °C for 1 h to remove residual moisture and to promote adhesion between the FLG and the polymer matrix.

2.4. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

The chemical structure of the TPU-based films was analyzed using a Frontier FT-IR/NIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) operating in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode, equipped with a diamond crystal. Spectra were recorded at room temperature in the range of 650–4000 cm−1, averaging 64 scans with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. Samples included the four pristine TPU matrices, the corresponding TPU/PVP blends, and the TPU-based coatings. The analysis aimed to identify the primary functional groups and evaluate potential interactions among TPU, PVP, and FLG. Spectral data were processed and analyzed using OriginPro 8.5.0 SR1 software (version 85E, OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

2.5. Thermal Analysis

Thermal stability and decomposition behavior of the TPU-based coatings were assessed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Model Q500, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) under a nitrogen atmosphere (30 mL/min flow rate). Samples (~8 mg) were heated from 30 °C to 800 °C at 10 °C/min. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, TA Instruments Q2000, USA) was used to analyze the glass transition temperature (Tg) in a heat–cool–heat mode, with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 over the temperature range from −80 °C to 250 °C. Samples were sealed in standard aluminum pans, and the data were processed using the TA Universal Analysis software v5.10.

2.6. Morphological Analysis

The morphological characteristics of the coatings were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Quanta 200 FEG, FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Samples were sputter-coated with a gold–palladium (Au-Pd) layer (~10 nm) before imaging. The surface micrographs were obtained at 10,000× magnification to evaluate FLG dispersion and interfacial interactions between graphene and the polymer matrix.

Quantitative roughness analyses (Ra and Rq) were performed on the SEM images, with values calculated using Gwyddion 2.66 software. For the measurement, three replicates of the same coating were analyzed, with five lines of 20 µm evaluated in each replicate to obtain the averaged roughness values.

2.7. Wettability Analysis

Static contact angle measurements were performed using an optical contact angle instrument (OCA 20, Dataphysics Instruments, Filderstadt, Germany) to evaluate the wettability with polar (water) and apolar (diiodomethane, DIM) solvents to determine the polar and dispersive components of the surface free energy of the selected substrates and coating formulations. A 1 μL droplet was dispensed on each surface, and the contact angle was determined by the sessile drop method. Measurements were taken at ten points on each sample, and the reported value represents the average of these readings’ contact angles. Thin coating layers were prepared using a roll-coating system with a 50 μm wire bar to ensure uniform film thickness.

The total surface free energy (

γS) of the samples was calculated using the Owens–Wendt equation (mN/m) [

28]:

where

is the total surface tension of the liquid;

and are the dispersive and polar components of the liquid surface tension;

and are the dispersive and polar components of the solid surface free energy;

and is the contact angle between the liquid and the solid surface.

The total surface free energy of the solid was obtained as the sum of its dispersive and polar components:

Since two unknowns ( and ) are present, measurements with at least two test liquids of known surface tension components ( and ) were used to establish a system of two equations, which was solved to determine the dispersive and polar contributions of the solid surface.

2.8. Electrical Resistivity and Washability Tests

The electrical performance of the TPU-based coatings was evaluated by measuring the sheet resistance (

Rs) using a four-probe tester (Multimeter 34401A 6½ Digit, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Measurements were performed on conductive tracks of varying width to verify the uniformity and reproducibility of the deposited coatings. The sheet resistivity expressed in ohms per square (Ω/□) was calculated from the measured resistance values according to Ohm’s law:

where

Rs is the sheet resistance (Ω/□),

R is the measured electrical resistance (Ω),

W is the track width (mm), and

L is the track length (mm).

Each data point represents the average value obtained from at least ten independent measurements performed on three different conductive sheets.

The wash durability of the TPU-based coatings was evaluated through repeated wash/drying cycles. Samples were immersed in deionized water containing a mild detergent and magnetically stirred at 500 rpm for 1 h per cycle at room temperature. After each cycle, the coated films were dried at 40 °C for 1 h, and their electrical resistance was measured. The washing procedure was repeated for up to 180 cycles to assess long-term stability.

3. Results

3.1. FT-IR Analysis

FT-IR analysis, shown in

Figure 2a, highlighted the characteristic features of the hard and soft segments (

Figure 2c) of the investigated TPUs. The chemical structure of the TPU-based coatings was studied to identify the possible interactions with the PVP structure (

Figure 2c) and FLG. In the hard segments, the band at ~1700 cm

−1, attributed to the C=O stretching of urethane linkages, was visible in all samples; in BIO E02 and U6150, an additional shoulder was observed, suggesting the presence of carbonyl groups in different chemical environments. The N-H stretching of urethane groups, detected at ~3300 cm

−1, further confirmed the organization of the hard domains [

18].

Regarding the soft segments, several diagnostic bands were identified. The band at ~1250 cm−1 corresponds to contributions from both carbonates and esters (as in BIO S03), while the band at ~1170 cm−1 is typical of esters. The absorption bands in the 1080–1240 cm−1 region provide additional insights into the degree of interaction between hard and soft segments. In particular, the band at 1240 cm−1 is characteristic of amide III groups.

This band is absent in BIO S03, indicating a low content of hard segments. This is further supported by the spectral region between 1680 and 1760 cm

−1, which provides information on the extent of free and hydrogen-bonded carbonyl groups. In this range, the presence of shoulders around the main bonded carbonyl peak suggests complex interactions involving urethane N-H groups and both hard and soft segment carbonyls. For U6150 and U4190, a pronounced shoulder associated with bonded carbonyls is observed, indicating strong interactions and a higher proportion of hard segments. This effect becomes even more pronounced in BIO E02, consistent with its structural features, which are particularly rich in hard segments. In contrast, the predominance of soft segments in BIO S03 results in a blue shift of the 1735 cm

−1 band, attributed to interactions between the N-H groups of the hard segments and the carbonyls of the soft segments [

29,

30].

The O–C(=O)–O stretching, observed between 1216 and 1257 cm

−1, was detected in BIO E02 and U6150. Finally, the C=O stretching of polyester polyols appeared at ~1735 cm

−1, with an additional shoulder in BIO E02 and U6150, indicating different environments of carbonyl groups [

31].

Notably, in the BIO E02/PVP/FLG, a slight shift in the polycarbonate carbonyl band was observed compared to the pristine TPU, suggesting a hydrogen-bonding network between the C=O groups of the polycarbonate segments and the pyrrolidone rings of PVP [

32], which could influence both the morphology and the filler dispersion, as confirmed by SEM observations.

After the addition of FLG, some characteristic absorption bands, particularly those associated with surface or polar groups, appeared more intense or partially overlapped, i.e., the bands at 1250 cm

−1 or 1735 cm

−1 (

Figure 2). This effect can be attributed to both the strong absorbance of graphene in the mid-infrared region and the physical interactions between FLG and the polymer matrix, which may locally affect the vibrational environment of the functional groups [

18].

3.2. Thermal Analysis

TGA and dTGA analysis, shown respectively in

Figure 3a,b, highlighted relevant differences in the thermal stability of the investigated TPUs (

Table 2). The onset temperature (T

onset) ranged from 163 °C for BIO E02 to 269 °C for U4190, reflecting the different chemical architectures. All pristine TPUs showed two main degradation steps: the first one, in a range of 160 and 270 °C, is associated with the soft segments decomposition (mainly polyester polyols); the second one, in a range of 330 to 470 °C, is attributed to the hard domains (urethane and urea linkages) [

33]. In particular, U4190 exhibited T2nd at 380 °C and T2nd

_f at 408 °C, while BIO S03 degraded earlier (334–401 °C).

Upon addition of PVP and FLG, a stabilization effect was observed. In U4190/PVP/FLG and U6150/PVP/FLG, the second degradation step was shifted to higher temperatures (407–435 °C and 392–441 °C, respectively). In the case of bio-based TPUs, the effect was even more pronounced: BIO E02/PVP/FLG displayed a new degradation step (500 and 699 °C), while BIO S03/PVP/FLG developed a third degradation step (516–535 °C). These suggest PVP interaction with TPU hard segments, modifying the molecular organization and suppressing or shifting the typical second stage of degradation. Such stabilization is consistent with the improved miscibility and hydrogen-bonding interactions.

The DSC reported in

Figure 3c confirmed predominance of the amorphous phase in all investigated TPUs, and no distinct melting or crystallization peaks were detected. Only a broad glass transition, typically between −50 °C and −40 °C, are observed, which is consistent with the flexible amorphous character of these aliphatic TPUs [

19].

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

The surface morphology, shown in

Figure 4, reports differences in TPU-based coatings that can be attributed to the specific segmental composition and polarity of each TPU. U6150, characterized by a balanced ratio between hard and soft segments and a higher density of urethane linkages, exhibited the most compact and homogeneous surface. This microstructure suggests strong intermolecular interactions and good interfacial compatibility with PVP and FLG, which promote uniform dispersion of the conductive filler within the polymeric matrix.

U4190, although predominantly composed of soft aliphatic segments, as discussed in the FT-IR paragraph, displayed a homogeneous morphology, which results from favorable hydrogen-bonding interactions between the urethane groups and the PVP, which assist in stabilizing the graphene sheets and maintaining an even surface texture [

14,

34].

On the other hand, the BIO S03 and BIO E02 samples showed less homogeneous surfaces with evident aggregates and discontinuities (

Figure 4c,d). In the BIO S03 film, the nearly complete absence of hard segments leads to higher chain mobility and partial phase separation, producing irregular polymeric domains visible in the SEM images (

Figure 4c). The BIO E02 coating, despite its higher hard-segment content, contains a significant fraction of carbonyl and polycarbonate groups that have low compatibility with the amphiphilic PVP. As a result, it is possible to observe localized clusters and surface defects.

3.4. Wettability Analysis

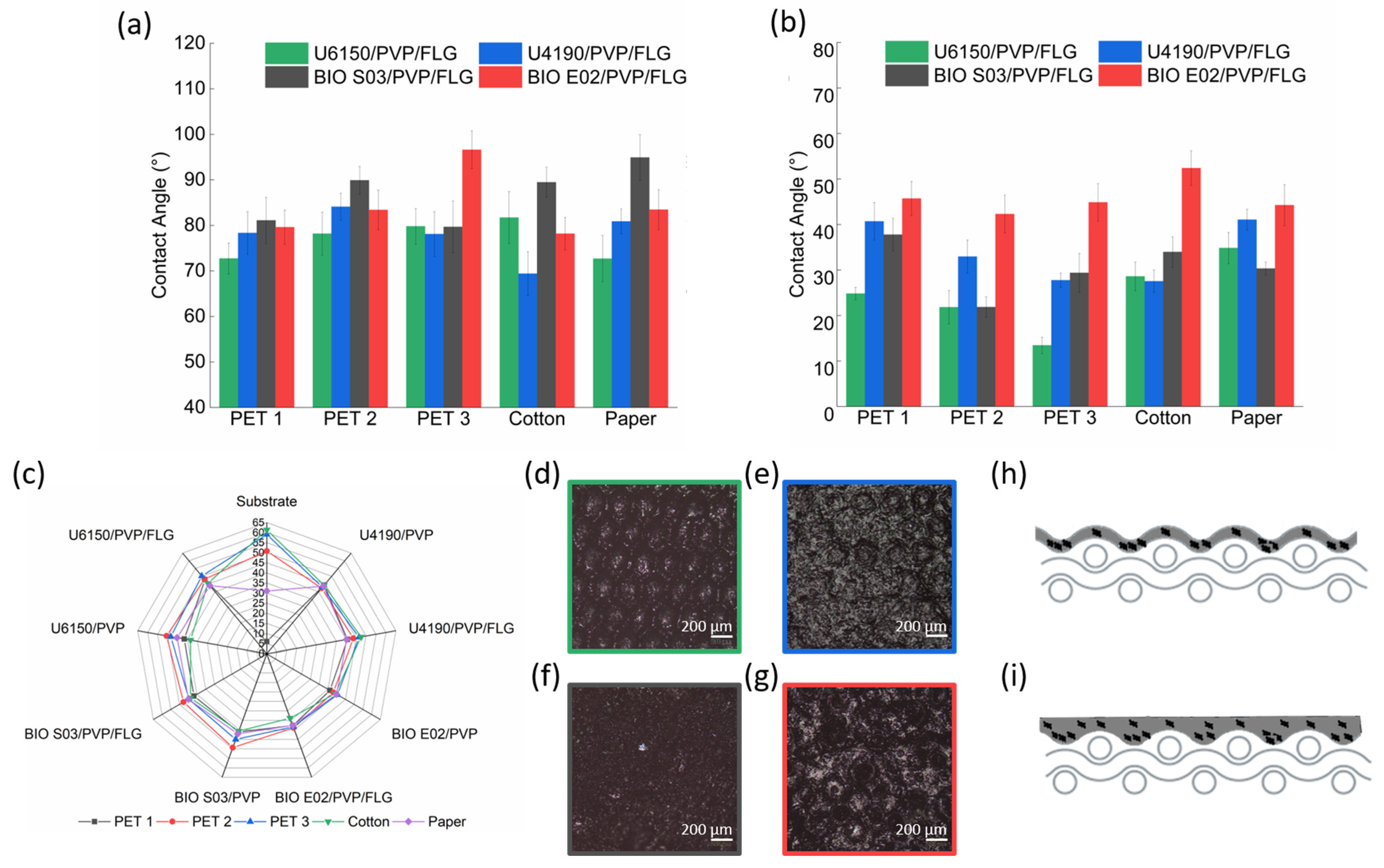

The wettability of the selected substrates was evaluated by measuring the static contact angles using water (

Figure 5a) and DIM (

Figure 5b) as polar and apolar solvents, respectively.

The results show a trend in the surface polarity among the different materials. Cotton and paper exhibit low contact angles with water, confirming their highly hydrophilic and polar character, whereas the three PET fabrics display progressively lower contact angles, consistent with their more hydrophobic characteristics. The measurements with DIM reveal a complementary behavior, with a gradual variation across the PET samples, indicating controlled differences in their surface chemistry or topography. This trend confirms that the PET fabrics possess distinct degrees of apolar character, which are expected to influence the interaction with the TPU-based coatings.

The hard segments of TPU, primarily urethane and carbonyl groups, increase the polar character of the polymer and favor adhesion to hydrophilic surfaces. Conversely, the soft segments, typically polyester or polycarbonate chains, are more hydrophobic and adhere more effectively to apolar substrates [

18]. PVP is an amphiphilic polymer, and its polar chains interact with hydrophilic substrates, while its pyrrolidone rings engage in π–π and dipolar interactions with hydrophobic surfaces [

13].

The DIM measurements (

Figure 5b) suggest favorable interactions between the TPU soft segments and apolar surfaces. In contrast, cotton and paper, which are polar substrates, show an opposite behavior, likely due to their different surface chemistry, with functional groups that interact strongly with the polar coating components. The intrinsic roughness of the substrates may also influence wetting behavior: the relatively smooth surfaces of PET tend to improve coating distribution, while increased roughness increases apparent hydrophilicity and may lead to partial penetration of the water-based formulation into the porous structure, as reported in previous studies on polyurethane-coated few-layer graphene-based textiles [

15].

The incorporation of FLG slightly increased the surface energy of the formulations, enhancing the adhesion of the liquid film to the substrates. To visualize this trend, radar plots were generated based on surface energy values calculated using the Owens–Wendt approach (

Figure 5c). This effect was particularly evident for the U6150/PVP/FLG and U4190/PVP/FLG coatings on cotton and PET 3.

As seen in

Figure 5d–f, lower water contact angles promote spreading and penetration of the liquid film into the fibrous network, which makes the underlying texture more visible (refer to PET3, selected as the most representative substrate due to its stronger sensitivity to variations in coating polarity and its well-defined surface response). This observation suggests that wettability directly affects the final coating morphology. This phenomenon may lead to local accumulation of FLG within the inter-yarn gaps. Lower water wettability, as observed for BIO S03/PVP/FLG, reduces infiltration into the substrate and favors the formation of a more continuous and uniform surface, with a more homogeneous distribution of graphene, as schematically represented in

Figure 5h,i.

3.5. Electrical Resistivity and Washability Tests

The electrical performance of the TPU-based coatings on the textile was evaluated by measuring the sheet resistance of the deposited films before washing (

Figure 6).

Among the tested formulations, U6150/PVP/FLG and U4190/PVP/FLG exhibited the lowest sheet resistance values in the range of 10

5 Ω/□ on PET 2, PET 3, and cotton, indicating that the formation of conductive networks increases when the hydrophilicity of the substrates increases. This behavior can be attributed to the balanced hard–soft segment ratio and the higher density of urethane groups in these TPUs, which promote favorable interactions with PVP and facilitate the uniform dispersion of graphene [

35,

36]. In contrast, BIO E02-based coatings showed significantly higher resistivity, up to 10

6 Ω/□ on any substrates, consistent with the less homogeneous morphology observed by SEM and the lower affinity with the PVP. BIO S03 displayed good interaction with PET 2, ~10

4 Ω/□, which is considered a conductivity value [

15], suggesting the formation of a conductive pathway, correlated with its predominantly soft-segment composition, when interacting with hydrophobic substrates. In fact, the same coating on PET 3 increases the resistivity and completely loses the conductive behavior on cotton (

Figure 6).

As these are water-based composites, PET 1 (a water-repellent fabric) does not allow for conductive coatings. This demonstrates that the electrical properties of a composite depend on its formulation and on the substrate on which the coating is deposited.

The electrical performance during repeated washing cycles was investigated to evaluate the stability of the TPU-based coatings. All specimens maintained their structural integrity after multiple washing steps; however, a progressive increase in sheet resistance was observed. The U6150/PVP/FLG coatings demonstrated the highest stability, retaining more than 80% of their initial conductivity after 180 washing cycles on PET 3 and cotton. The U4190/PVP/FLG films also exhibited good durability on substrates that exhibit a low water contact angle value. In contrast, BIO E02 coatings showed a degradation of electrical performance, consistent with their lower interfacial affinity and less compact morphology. The BIO S03 resistivity value remain unchanged on PET 2 and PET 3 after the washing cycle, demonstrating good affinity with these textile and water-wash durability.

The electrical results obtained in this work (Rs ≈ 100–200 Ω/□ for the most conductive samples after washing), combined with their stability up to 180 washing cycles, are comparable to those reported for other washable conductive coatings based on different fillers. For example, MXene-based coatings have shown very good washing stability, with some studies reporting only minimal changes in resistance after 45 h of accelerated laundering at 80 °C under continuous stirring, although such conditions cannot always be directly translated into a defined number of domestic wash cycles [

37].

Regarding PEDOT:PSS-based systems, several studies report very low initial sheet resistances (typically 1–10 Ω/□). Tadesse et al. demonstrated Rs ≈ 1.7 Ω/□ on polyamide/lycra textiles, maintaining good conductivity after ten standardized domestic washing cycles [

38], while the review by Alamer et al. reports cases where an initial Rs of 1.6 Ω/□ increases by only 6.2% after three detergent-based wash-and-dry cycles [

39]. Although PEDOT:PSS is widely regarded as a benchmark material for textile electronics, its processing is not always fully aligned with sustainability or bio-based criteria.

Also, Ag nanowire (AgNW) coatings also exhibit high conductivity (up to ~3668 S·cm

−1) and have been shown to withstand approximately twenty machine-washing cycles without obvious performance decay [

40].

The surface roughness analysis of roughness average (Ra) and root-mean-square roughness (Rq) on the SEM image reveals distinct morphological differences among the four samples. U6150/PVP/FLG exhibits the lowest Ra value (14.54 × 10−3 mm), indicating the smoothest average surface; however, its relatively high Rq/Ra ratio (1.64) suggests a less uniform topography with more pronounced localized asperities. In contrast, U4190/PVP/FLG and BIO S03/PVP/FLG display higher Ra values (19.24 × 10−3 and 20.62 × 10−3 mm, respectively) but lower Rq/Ra ratios (1.34 and 1.33), reflecting rougher yet more statistically homogeneous surfaces. BIO E02/PVP/FLG shows intermediate behavior, with an Ra comparable to U4190/PVP/FLG but a slightly higher Rq (Rq/Ra = 1.43), indicating a broader distribution of surface irregularities. These morphological features can influence the formation and continuity of conductive pathways within the films. Systems exhibiting a more homogeneous roughness distribution (e.g., U4190/PVP/FLG and BIO S03/PVP/FLG) promote improved interflake contact and reduced interruption of the percolation network, conditions typically associated with enhanced electrical conductivity.

Conversely, surfaces with localized sharp peaks and valleys, such as U6150/PVP/FLG, may introduce micro-gaps or localized stress points that hinder efficient electron transport despite their lower mean roughness. The interaction with surfaces that increase roughness and worsen wettability deteriorates percolation paths and therefore the ability to conduct electricity. On the other hand, improved wettability tends to make the coatings more uniform, resulting in improved electrical properties.

Figure 7 shows the coatings after washing, confirming the electrical resistivity trends. The BIO E02 films remained compact and strongly adhered to the substrate, consistent with their rigid microstructure and high hard-segment content, which promote interfacial stability during mechanical agitation. In contrast, the BIO S03 coatings exhibited good integrity on PET 2 and PET 3, in agreement with their stable electrical performance after multiple wash cycles. Minor surface irregularities were observed, without significant peeling, confirming the favorable interaction between the predominantly soft-segment TPU and the hydrophobic PET surfaces. U6150 and U4190-based coatings, while retaining electrical continuity, exhibited localized detachment on the most hydrophobic PET fabrics, indicating that substrate polarity still affects the mechanical anchoring of the conductive layer. The wash durability results confirm that TPU segmental architecture affecting the electrical stability also determines the long-term adhesion of the coatings.

The performance of the proposed waterborne and bio-based graphene/TPU coatings compares favorably with other conductive systems reported in literature for wearable and washable electronics while offering the additional advantages of solvent-free processing and material sustainability. Çaylak et al. [

20] developed GNP/PVA/SDBS coatings on cotton fabrics that exhibited a surface resistance of approximately 1.9 kΩ/□ after seven washing cycles, despite using a filler percentage of 2.5 wt%. Similarly, Alamer and Aqiely [

4] achieved a surface resistance of 7.97 Ω·cm

−1 with 74 wt% graphite; however, conductivity decreased after just ten washing cycles. By contrast, the TPUs with a significantly lower filler loading of 2.5 wt% proposed in the present study retained their initial conductivity for up to 180 washing cycles, which demonstrates the efficiency and interfacial stability of the TPU matrix.