Fabrication of Silver-Doped UiO-66-NH2 and Characterization of Antibacterial Materials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

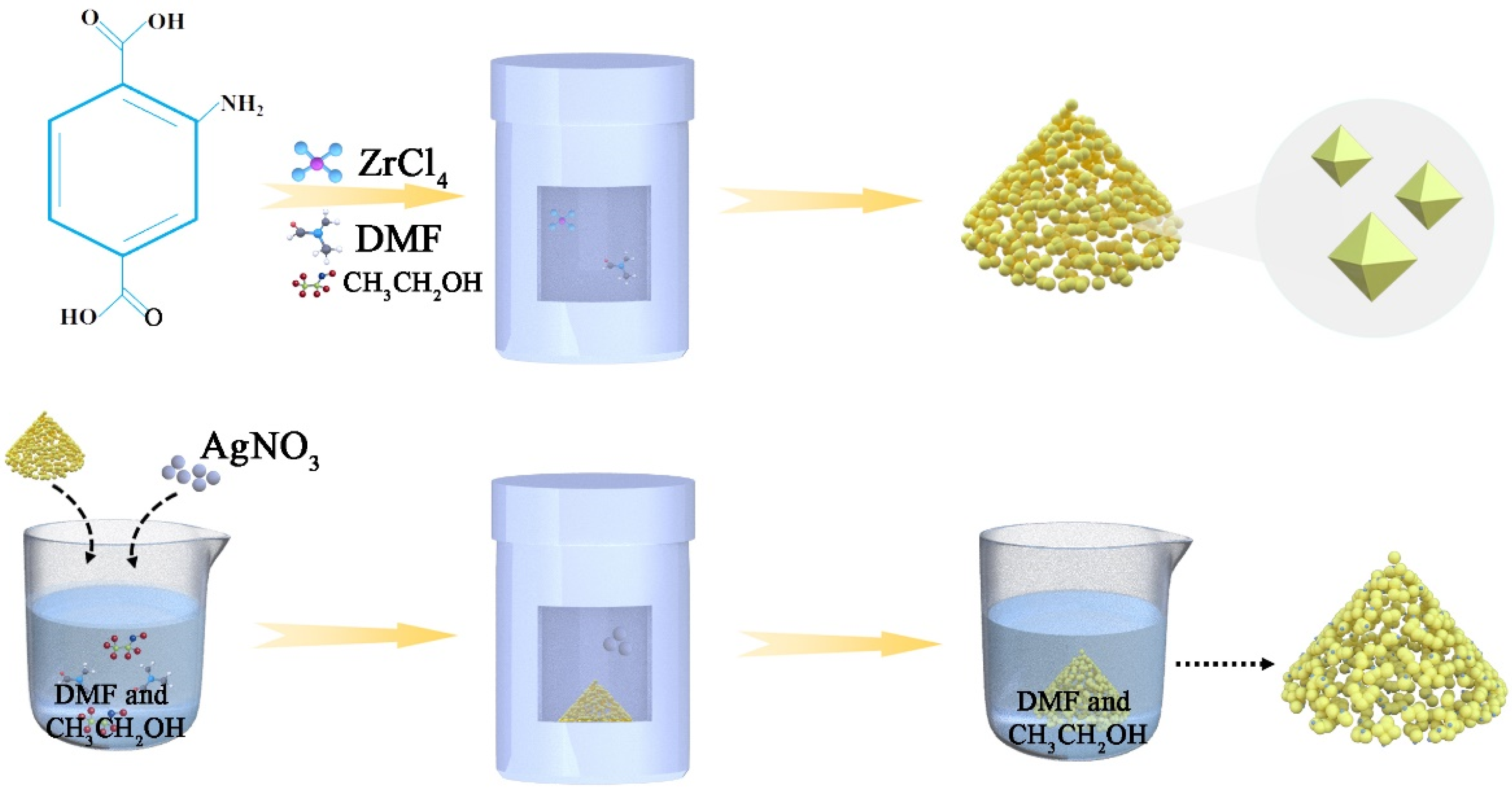

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Ag/UiO-66-NH2-Based Materials

3. Antibacterial Performance of the Ag/UiO-66-NH2 Materials

4. Results and Discussion

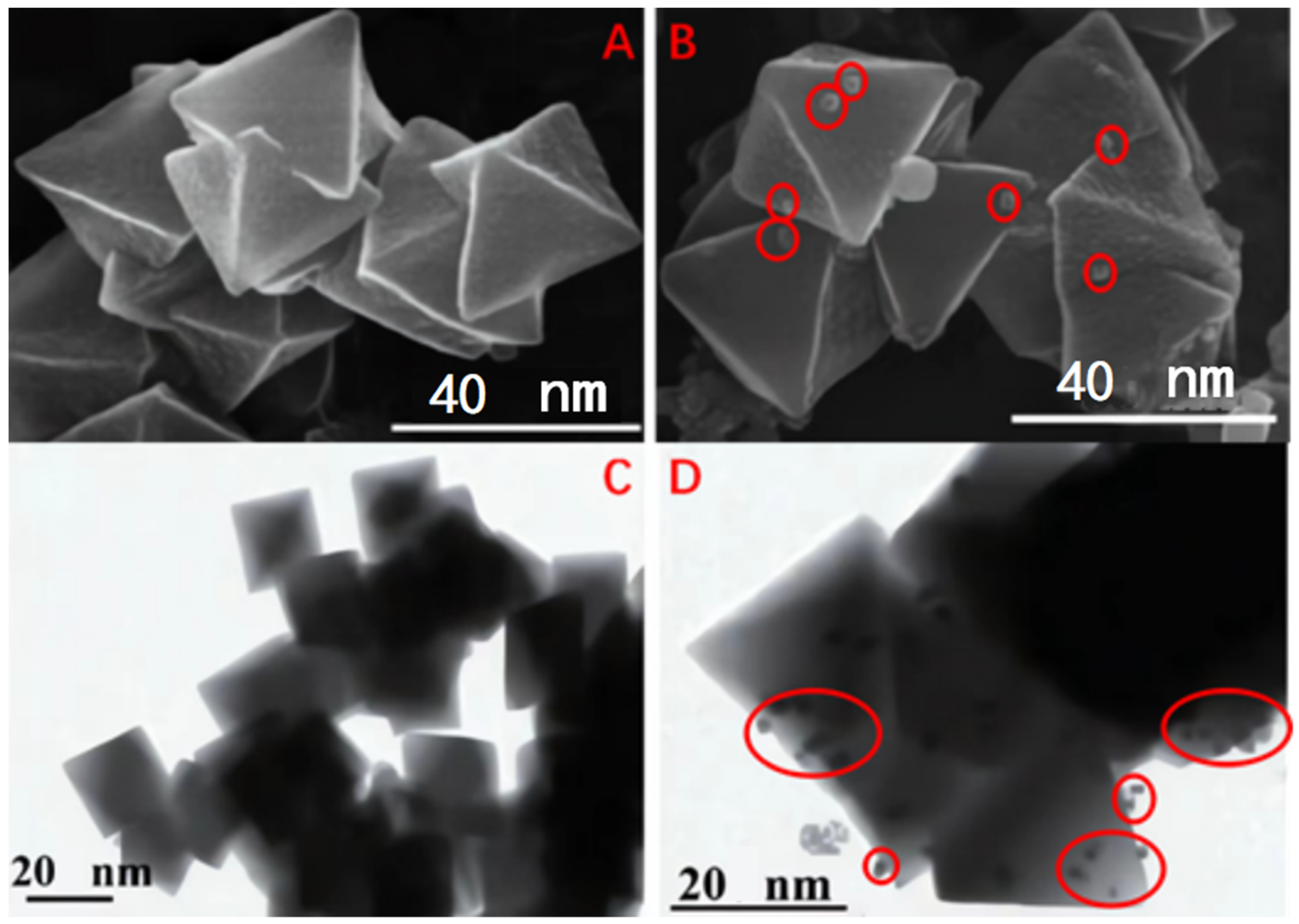

4.1. SEM Analysis

4.2. XRD Analysis

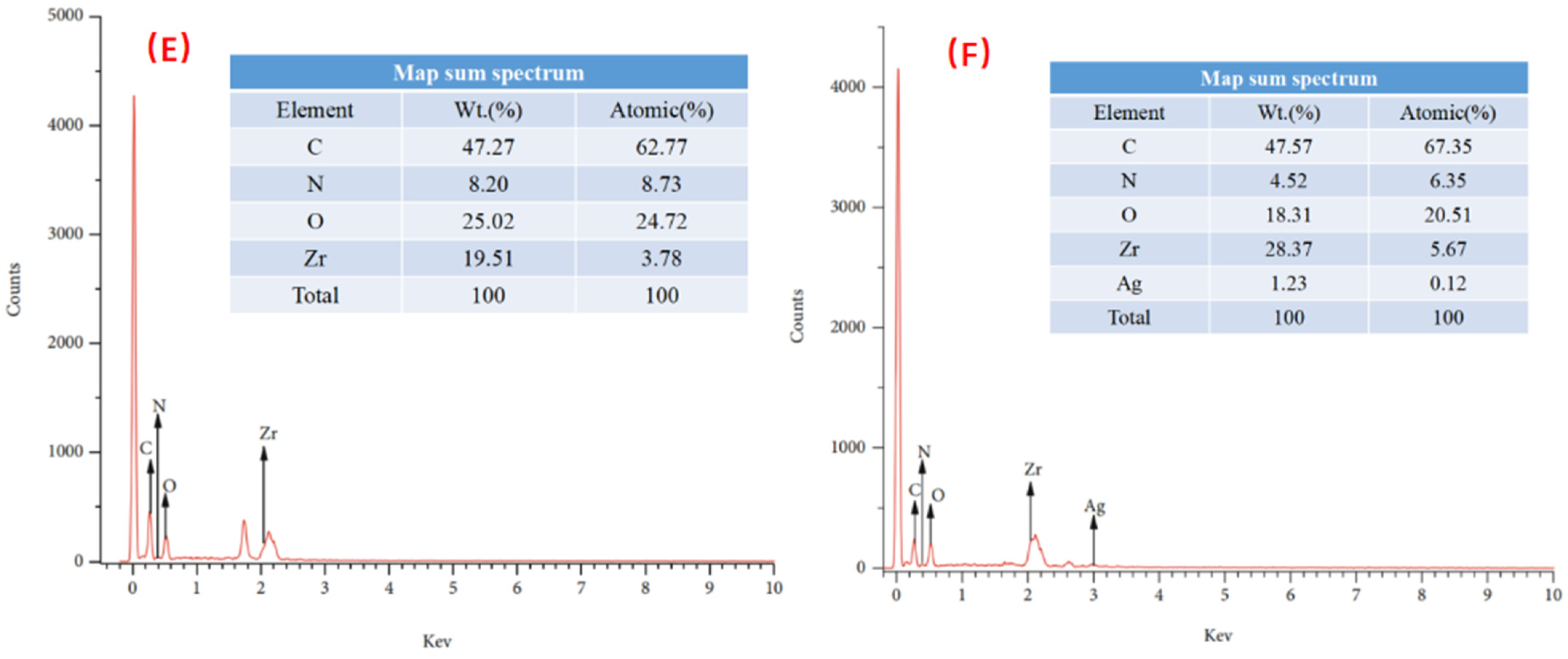

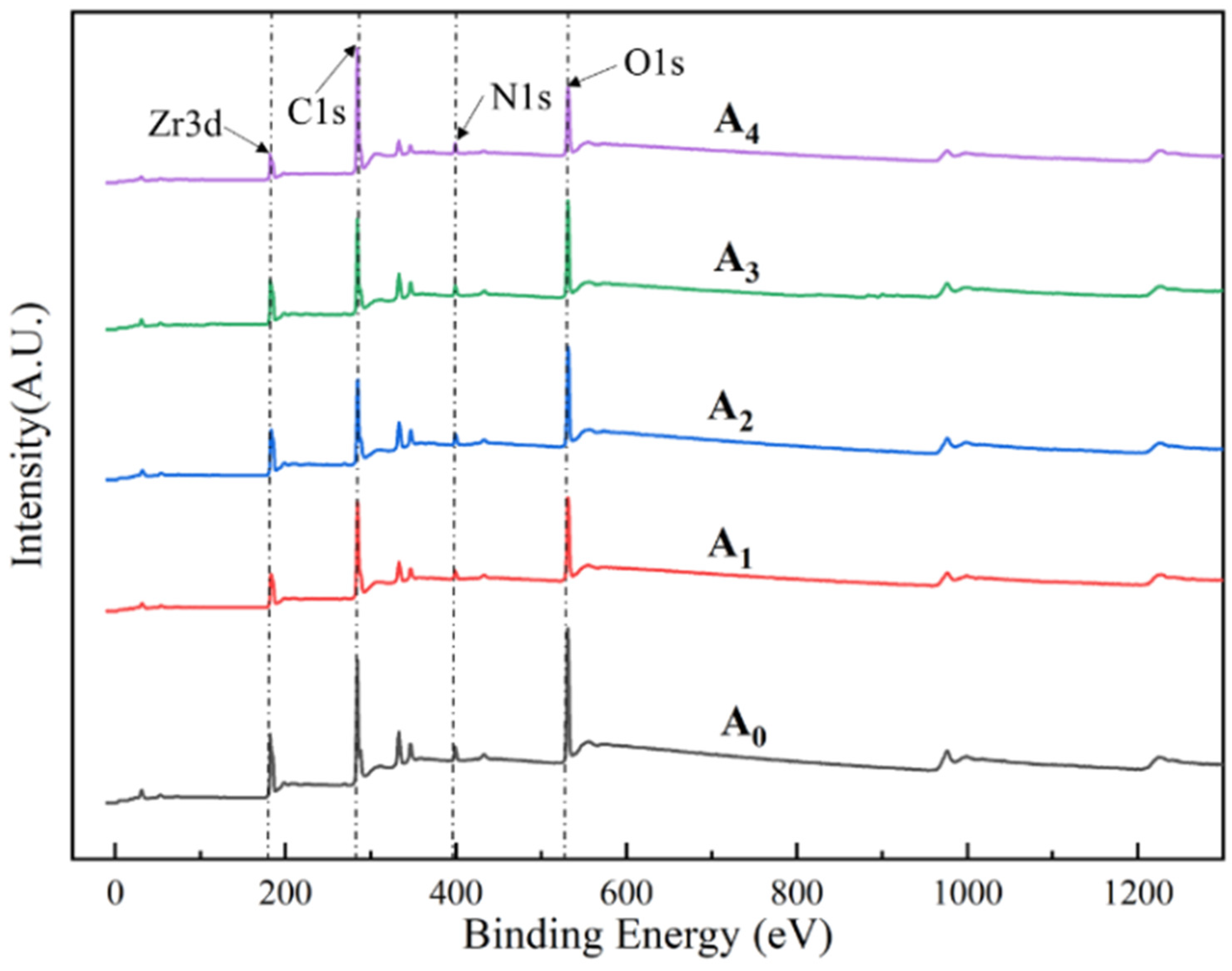

4.3. XPS Analysis

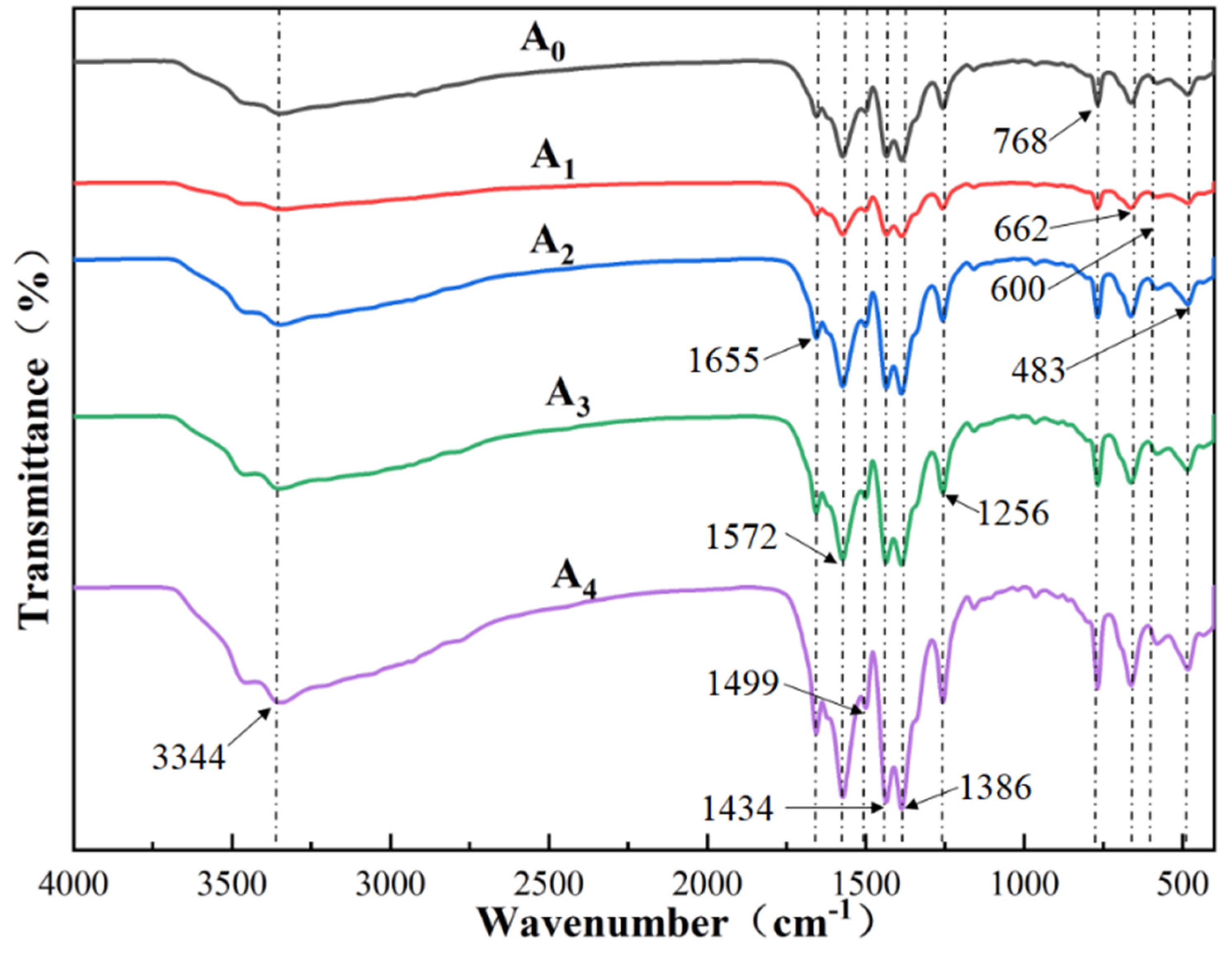

4.4. FT-IR Analysis

4.5. BET Analysis

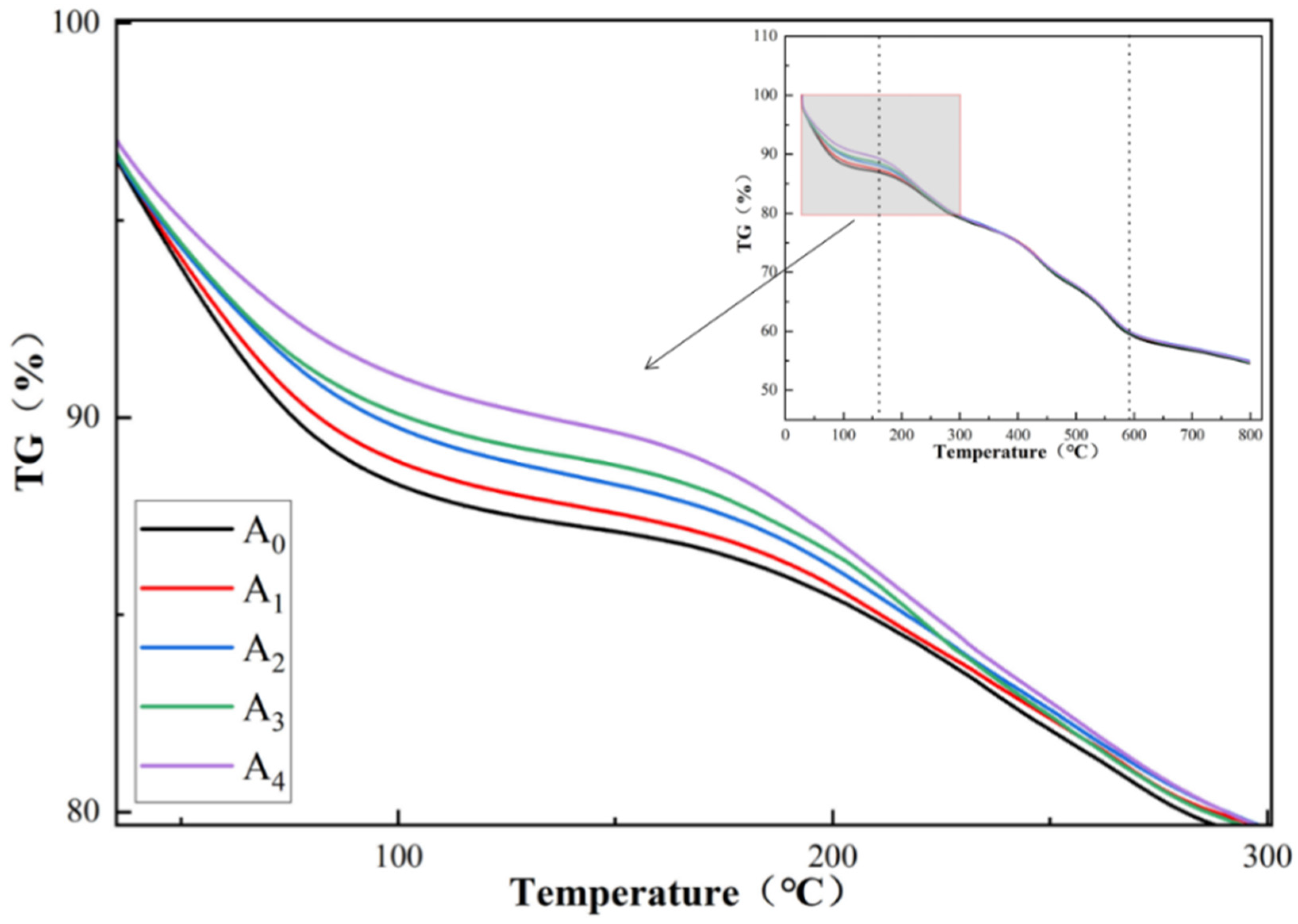

4.6. TGA Analysis

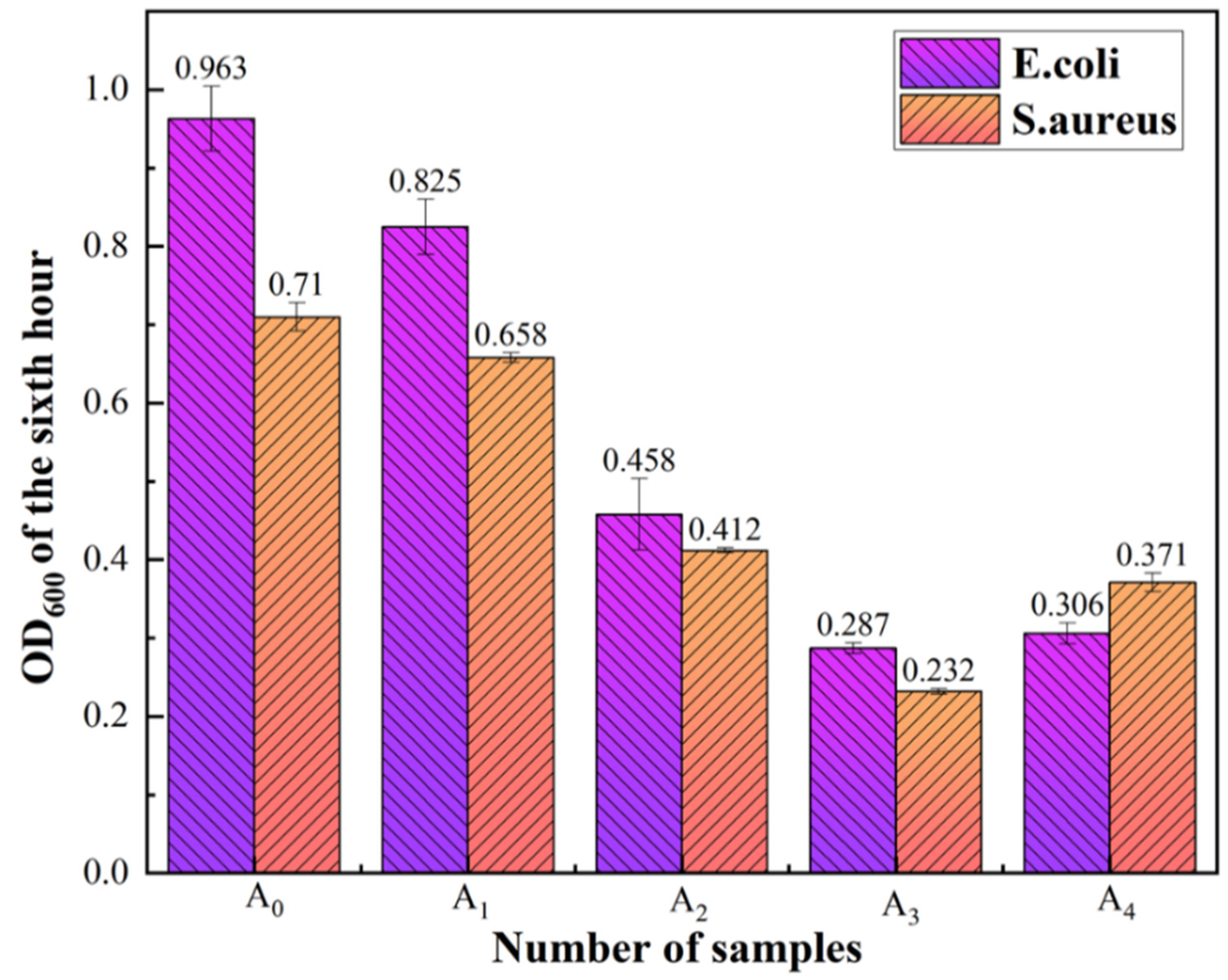

5. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Performance

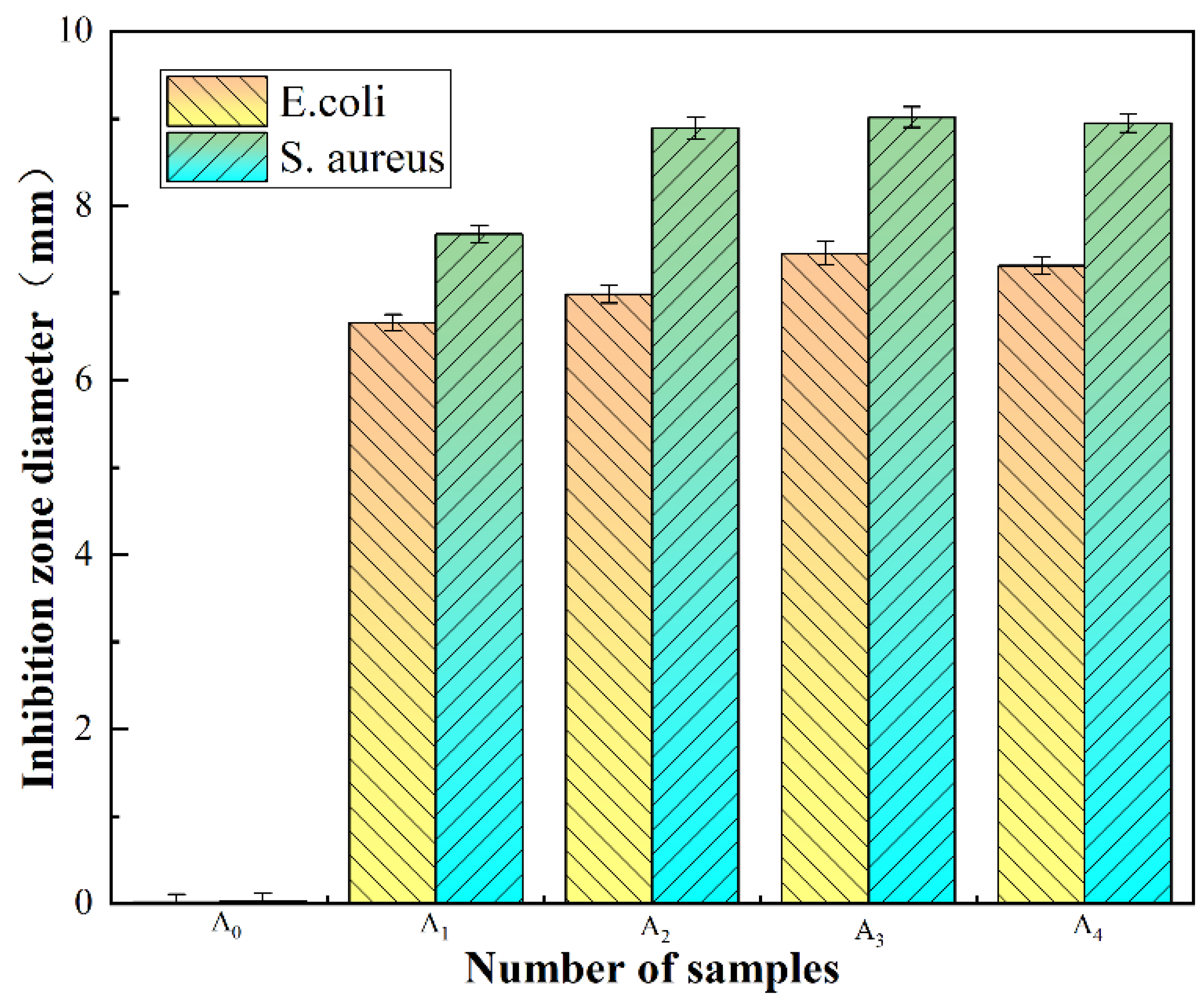

5.1. Inhibition Zone (ZOI)

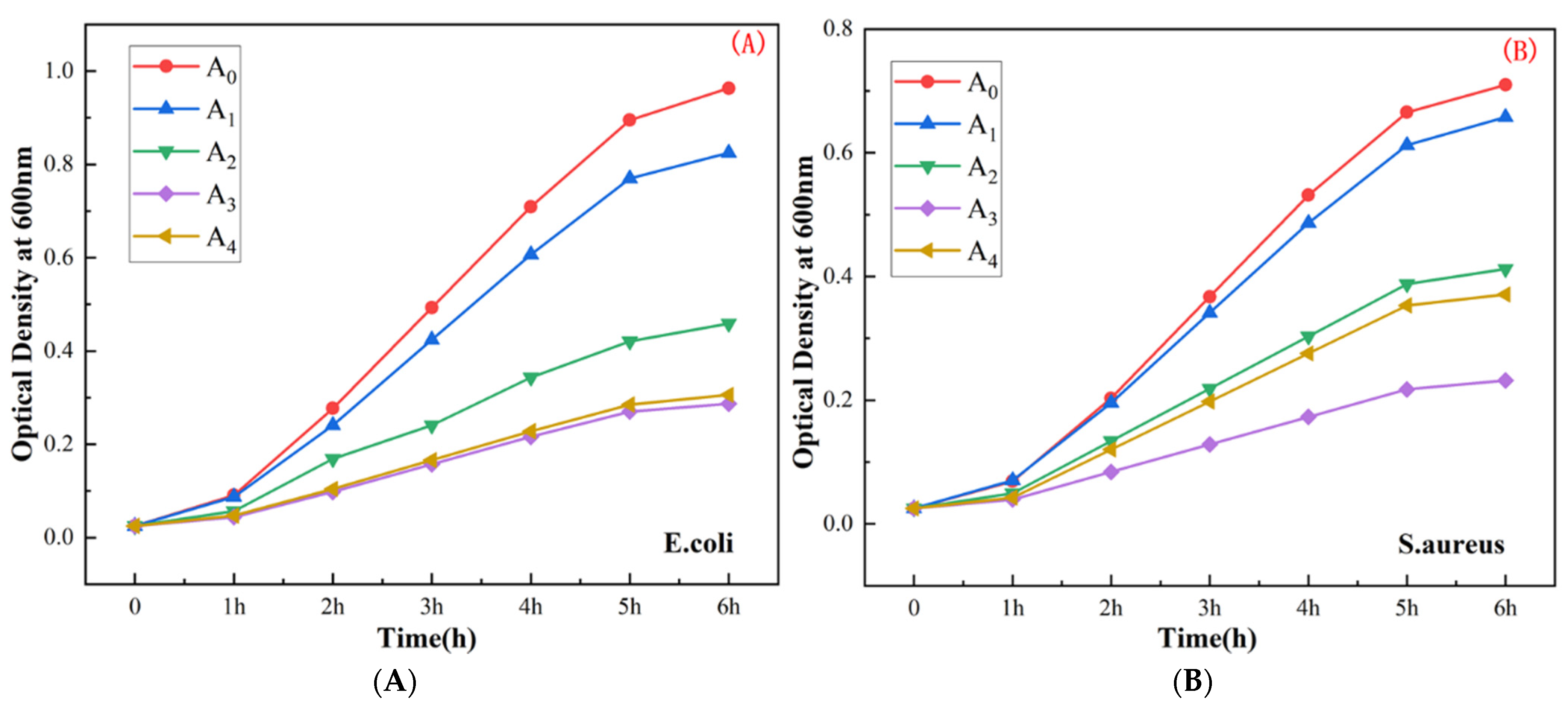

5.2. Determination of the Bacterial Growth Curve

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The introduction of Ag does not interfere with the crystallization of UiO-66-NH2. The morphology and crystal structure of the UiO-66-NH2 samples fabricated under conditions of varying silver ion doping levels amount are similar to those of UiO-66-NH2.

- (2)

- The FT-IR spectral profiles recorded for the UiO-66-NH2 samples fabricated under conditions of varying silver ion doping levels are similar to those recorded for UiO-66-NH2. Stray peaks were not observed, and the peak intensity decreased slightly.

- (3)

- The thermal stability of UiO-66-NH2, containing varying amounts of silver ions, was lower than the thermal stability of UiO-66-NH2. The higher the silver ion content, the lower the thermal stability. Under these conditions, the specific surface area and pore volume increased.

- (4)

- The antibacterial performance of UiO-66-NH2 improved significantly following the process of silver ion doping. As the silver ion content increased, the antibacterial performance improved initially and then deteriorated. The best antibacterial performance was observed when the silver ion content was 4 wt.%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cook, M.A.; Wright, G.D. The past, present, and future of antibiotics. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabo7793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanayakkara, A.K.; Boucher, H.W.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Jezek, A.; Outterson, K.; Greenberg, D.E. Antibiotic resistance in the patient with cancer: Escalating challenges and paths forward. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinemerem Nwobodo, D.; Ugwu, M.C.; Oliseloke Anie, C.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S.; Chinedu Ikem, J.; Victor Chigozie, U.; Saki, M. Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samreen Ahmad, I.; Malak, H.A.; Abulreesh, H.H. Environmental antimicrobial resistance and its drivers: A potential threat to public health. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 27, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzaque, M.S. Commentary: Microbial Resistance Movements: An Overview of Global Public Health Threats Posed by Antimicrobial Resistance, and How Best to Counter. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 629120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocsoy, I.; Gulbakan, B.; Chen, T.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Z.; Sari, M.M.; Peng, L.; Xiong, X.; Fang, X.; Tan, W. DNA-guided metal-nanoparticle formation on graphene oxide surface. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2319–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocsoy, I.; Paret, M.L.; Ocsoy, M.A.; Kunwar, S.; Chen, T.; You, M.; Tan, W. Nanotechnology in plant disease management: DNA-directed silver nanoparticles on graphene oxide as an antibacterial against Xanthomonas perforans. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 8972–8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakamura, S.; Sato, M.; Sato, Y.; Ando, N.; Takayama, T.; Fujita, M.; Ishihara, M. Synthesis and Application of Silver Nanoparticles (Ag NPs) for the Prevention of Infection in Healthcare Workers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalaivani, R.; Maruthupandy, M.; Muneeswaran, T.; Hameedha Beevi, A.; Anand, M.; Ramakritinan, C.M.; Kumaraguru, A.K. Synthesis of chitosan mediated silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) for potential antimicrobial applications. Front. Lab. Med. 2018, 2, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawar, S.N.; Al-Shmgani, H.S.; Al-Kubaisi, Z.A.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Dewir, Y.H.; Rikisahedew, J.J.; Omri, A. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Alhagi graecorum Leaf Extract and Evaluation of Their Cytotoxicity and Antifungal Activity. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 1058119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rugaie, O.; Jabir, M.S.; Mohammed, M.K.A.; Abbas, R.H.; Ahmed, D.S.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Mohammed, S.A.A.; Khan, R.A.; Al-Regaiey, K.A.; Alsharidah, M.; et al. Modification of SWCNTs with hybrid materials ZnO-Ag and ZnO-Au for enhancing bactericidal activity of phagocytic cells against Escherichia coli through NOX2 pathway. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibraheem, D.R.; Hussein, N.N.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Mohammed, H.A.; Khan, R.A.; Al Rugaie, O. Ciprofloxacin-Loaded Silver Nanoparticles as Potent Nano-Antibiotics against Resistant Pathogenic Bacteria. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, P.; Altuntas, S.; Mondal, R.; Baudrit, J.R.V.; Kati, A.; Ghorai, S.; Sadat, A.; Gangopadhyay, D.; Shaw, S.; Franco, O.L.; et al. Silk-based nano-biocomposite scaffolds for skin organogenesis. Mater. Lett. 2022, 327, 133024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khane, Y.; Benouis, K.; Albukhaty, S.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Abomughaid, M.M.; Al Ali, A.; Aouf, D.; Fenniche, F.; Khane, S.; Chaibi, W.; et al. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Citrus limon Zest Extract: Characterization and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, A.; Ocsoy, I.; Tan, W.; Jones, J.B.; Paret, M.L. Low Concentrations of a Silver-Based Nanocomposite to Manage Bacterial Spot of Tomato in the Greenhouse. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1460–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leng, Y.; Fu, L.; Ye, L.; Li, B.; Xu, X.; Xing, X.; He, J.; Song, Y.; Leng, C.; Guo, Y.; et al. Protein-directed synthesis of highly monodispersed, spherical gold nanoparticles and their applications in multidimensional sensing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Liu, C.; Meng, X.; Lu, W.; Ni, Y. Fabrication of carboxymethylated cellulose fibers supporting Ag NPs@MOF-199s nanocatalysts for catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 33, e4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukoyoshi, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Kusada, K.; Hayashi, M.; Yamada, T.; Maesato, M.; Taylor, J.M.; Kubota, Y.; Kato, K.; Takata, M.; et al. Hybrid materials of Ni NP@MOF prepared by a simple synthetic method. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12463–12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dai, S.; Ngoc, K.P.; Grimaud, L.; Zhang, S.; Tissot, A.; Serre, C. Impact of capping agent removal from Au NPs@MOF core-shell nanoparticle heterogeneous catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 3201–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Yan, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.C.; Jiang, H.L. Metal-Organic Framework-Based Hierarchically Porous Materials: Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12278–12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacourbaravi, R.; Ansari-Asl, Z.; Kooti, M.; Nobakht, V.; Darabpour, E. Fabrication of Ag NPs/Zn-MOF Nanocomposites and Their Application as Antibacterial Agents. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 4615–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, F.; Jiang, C.; Ye, S.; Tong, J.; Dramou, P.; He, H. Recent progress in the construction and applications of metal-organic frameworks and covalent-organic frameworks-based nanozymes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 471, 214760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Xue, W.; Huang, H.; Zhu, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, C. Mechanochemistry-assisted linker exchange of metal-organic framework for efficient kinetic separation of propene and propane. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Su, P.; Li, W. Chemical vapor deposition of guest-host dual metal-organic framework heterosystems for high-performance mixed matrix membranes. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 27, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hou, X.; Dekyvere, S.; Mousavi, B.; Chaemchuen, S. Single-thermal synthesis of bimetallic Co/Zn@NC under solvent-free conditions as an efficient dual-functional oxygen electrocatalyst in Zn-air batteries. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 16683–16694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharramnejad, M.; Ehsani, A.; Salmani, S.; Shahi, M.; Malekshah, R.E.; Robatjazi, Z.S.; Parsimehr, H. Zinc-based metal-organic frameworks: Synthesis and recent progress in biomedical application. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2022, 32, 3339–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhou, T.; Chen, X.; Li, W.; Pang, H. Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Composites for Environmental Applications. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2204141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhou, M.; Bai, J.; Bo, X. Fast and Facile Room-Temperature Synthesis of MOF-Derived Co Nanoparticle/Nitrogen-Doped Porous Graphene in Air Atmosphere for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11947–11955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, W.; Xu, H.; Deng, H. Facile Synthesis of Uniform Metal Carbide Nanoparticles from Metal-Organic Frameworks by Laser Metallurgy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 44573–44581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.-L.; Su, J.; Muhammad, N.; Zheng, W.T.; Yue, C.-L.; Liu, F.-Q.; Zuo, J.-L.; Ding, Z.-J. Facile encapsulating Ag nanoparticles into a Tetrathiafulvalene-based Zr-MOF for enhanced Photocatalysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereketova, A.; Nallal, M.; Yusuf, M.; Jang, S.; Selvam, K.; Park, K.H. A Co-MOF-derived flower-like CoS@S,N-doped carbon matrix for highly efficient overall water splitting. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 16823–16833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Zhao, C.; Ji, J.; Chen, W.; Ding, N.; Li, S.; Pang, S. Simple and selective method for simultaneous removal of mercury(ii) and recovery of silver(i) from aqueous media by organic ligand 4,4′-azo-1,2,4-triazole. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2022, 8, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Dong, Y.; Wang, R.; Pan, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Liu, D.; Liu, J. Recent developments on MOF-based platforms for antibacterial therapy. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Chu, D.; Zhu, X.; Xue, B.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Z.; Li, J. Silver nanoparticle-decorated 2D Co-TCPP MOF nanosheets for synergistic photodynamic and silver ion antibacterial. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 33, 128524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, D.; Sun, X.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L. Surface modified by green synthetic of Cu-MOF-74 to improve the anti-biofouling properties of PVDF membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 411, 128524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Pan, D.; Qiu, S.; Ren, L.; Huang, S.; Liu, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. Polyphenylene sulfide paper-based sensor modified by Eu-MOF for efficient detection of Fe3+. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 165, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzjaei, M.D.; Shamsabadi, A.A.; Sharifian Gh, M.; Rahimpour, A.; Soroush, M. A Novel Nanocomposite with Superior Antibacterial Activity: A Silver-Based Metal Organic Framework Embellished with Graphene Oxide. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1701365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedpour, S.F.; Arabi Shamsabadi, A.; Khoshhal Salestan, S.; Dadashi Firouzjaei, M.; Sharifian Gh, M.; Rahimpour, A.; Akbari Afkhami, F.; Shirzad Kebria, M.R.; Elliott, M.A.; Tiraferri, A.; et al. Tailoring the Biocidal Activity of Novel Silver-Based Metal Azolate Frameworks. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7588–7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, G.; Wang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Meng, W.; Zhang, X.; Du, F.; Lee, S. Ag@MOF-loaded chitosan nanoparticle and polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate/chitosan bilayer dressing for wound healing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 175, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Duan, J.; Hou, B.; Sheng, J. Combination of metal-organic framework with Ag-based semiconductor enhanced photocatalytic antibacterial performance under visible-light. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 644, 128813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L. Phenylthiosemicarbazide-functionalized UiO-66-NH2 as highly efficient adsorbent for the selective removal of lead from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 413, 125278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash Tripathy, S.; Subudhi, S.; Das, S.; Kumar Ghosh, M.; Das, M.; Acharya, R.; Acharya, R.; Parida, K. Hydrolytically stable citrate capped Fe3O4@UiO-66-NH2 MOF: A hetero-structure composite with enhanced activity towards Cr (VI) adsorption and photocatalytic H2 evolution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 606, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Liu, H.; Wu, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H. Fabrication of Uio-66-NH2 with 4,6-Diamino-2-mercaptopyrimidine facilitate the removal of Pb2+ in aqueous medium: Nitrogen and sulfur act as the main adsorption sites. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 236, 107431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-z.; Huang, T.; Zhang, N.; Hu, S.; Lei, Y.-z.; Wang, Y. Enhanced removal of lead ions and methyl orange from wastewater using polyethyleneimine grafted UiO-66-NH2 nanoparticles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 297, 121470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fan, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, S.; Laipan, M.; Ren, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Highly efficient and selective recovery of Au(III) from aqueous solution by bisthiourea immobilized UiO-66-NH2: Performance and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 130588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, F.S.; Bakry, A.M.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Lin, A.; El-Shall, M.S. Thiol- and Amine-Incorporated UIO-66-NH2 as an Efficient Adsorbent for the Removal of Mercury(II) and Phosphate Ions from Aqueous Solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 12675–12688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, M.N.; Kim, J.-O. Statistical optimization of Mg-doped UiO-66-NH2 synthesis for resource recovery from wastewater using response surface methodology. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 606, 154973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Peñas-Garzón, M.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Bedia, J.; Belver, C. Enhanced photodegradation of acetaminophen over Sr@TiO2/UiO-66-NH2 heterostructures under solar light irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, B.; Ge, Y.; Nie, P.; Yang, J.; Huang, M.; Liu, J. In-situ synthesis of UiO-66-NH2 on porous carbon nanofibers for high performance defluoridation by capacitive deionization. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 646, 129020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shi, W.; Ji, W.; Wu, H.; Gu, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Qin, P.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Y.; et al. Microenvironment of MOF Channel Coordination with Pt NPs for Selective Hydrogenation of Unsaturated Aldehydes. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5805–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, M.; Ashok, D.; Sen, T.; Enge, T.G.; Verma, N.K.; Tricoli, A.; Lowe, A.; Nisbet, D.R.; Tsuzuki, T. Stability of ZIF-8 nanopowders in bacterial culture media and its implication for antibacterial properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413, 127511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.A.; Choi, S.; Jeon, S.M.; Yu, J. Silica nanoparticle stability in biological media revisited. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chinnasamy, G.; Chandrasekharan, S.; Koh, T.W.; Bhatnagar, S. Synthesis, Characterization, Antibacterial and Wound Healing Efficacy of Silver Nanoparticles From Azadirachta indica. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 611560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnasamy, G.; Chandrasekharan, S.; Bhatnagar, S. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Melia azedarach: Enhancement of Antibacterial, Wound Healing, Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Activities. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9823–9836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Qin, J.; Yang, Z.; Fu, M. TiO2-UiO-66-NH2 nanocomposites as efficient photocatalysts for the oxidation of VOCs. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 385, 123814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gu, J.; Yin, N. Efficient Removal of Pb(II) and Cd(II) Using NH2-Functionalized Zr-MOFs via Rapid Microwave-Promoted Synthesis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 1880–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J. Preparation of Ag/UiO-66-NH2 and its application in photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) under visible light. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 4801–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Meng, Y.; Li, J. Highly enhanced adsorption performance of U(VI) by non-thermal plasma modified magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 513, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lv, Z.; Song, F.; Zhong, Q. Preparation and enhanced CO2 adsorption capacity of UiO-66/graphene oxide composites. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 27, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzjaei, M.D.; Shamsabadi, A.A.; Aktij, S.A.; Seyedpour, S.F.; Sharifian Gh, M.; Rahimpour, A.; Esfahani, M.R.; Ulbricht, M.; Soroush, M. Exploiting Synergetic Effects of Graphene Oxide and a Silver-Based Metal-Organic Framework to Enhance Antifouling and Anti-Biofouling Properties of Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 42967–42978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Dong, K.; Liu, Z.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Silver-Infused Porphyrinic Metal-Organic Framework: Surface-Adaptive, On-Demand Nanoplatform for Synergistic Bacteria Killing and Wound Disinfection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1808594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; He, B.; Liu, L.; Qu, G.; Shi, J.; Hu, L.; Jiang, G. Antibacterial mechanism of silver nanoparticles in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Proteomics approach. Metallomics 2018, 10, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Name | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Total Pore Volume (m3/g) |

|---|---|---|

| A0 | 462.96 | 0.16 |

| A1 | 465.25 | 0.16 |

| A2 | 527.74 | 0.18 |

| A3 | 574.93 | 0.20 |

| A4 | 741.60 | 0.27 |

| A0 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Average | 0.017 | 6.658 | 6.985 | 7.453 | 7.312 |

| Standard Deviation | 8.16 × 10−4 | 6.53 × 10−3 | 2.36 × 10−3 | 1.41 × 10−3 | 9.43 × 10−4 | |

| S. aureus | Average | 0.025 | 7.674 | 8.892 | 9.013 | 8.947 |

| Standard Deviation | 4.08 × 10−3 | 3.27 × 10−3 | 1.63 × 10−3 | 2.45 × 10−3 | 5.72 × 10−3 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, F.; Weng, R.; Huang, X.; Chen, G.; Huang, Z. Fabrication of Silver-Doped UiO-66-NH2 and Characterization of Antibacterial Materials. Coatings 2022, 12, 1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12121939

Tian F, Weng R, Huang X, Chen G, Huang Z. Fabrication of Silver-Doped UiO-66-NH2 and Characterization of Antibacterial Materials. Coatings. 2022; 12(12):1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12121939

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Feng, Rengui Weng, Xin Huang, Guohong Chen, and Zhitao Huang. 2022. "Fabrication of Silver-Doped UiO-66-NH2 and Characterization of Antibacterial Materials" Coatings 12, no. 12: 1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12121939

APA StyleTian, F., Weng, R., Huang, X., Chen, G., & Huang, Z. (2022). Fabrication of Silver-Doped UiO-66-NH2 and Characterization of Antibacterial Materials. Coatings, 12(12), 1939. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12121939