Bacteriophage-Based Control of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Anti-Biofilm Activity, Surface-Active Formulation Compatibility, and Genomic Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Bacterial Host Strains

2.2. Isolation of Bacteriophages from Environmental Samples

2.3. Detection of Bacteriophages by Spot Test

2.4. Phage Purification by Drop Plate Method

2.5. Host Range Screening by Spot Test

2.6. Evaluation of Phage Stability Under Temperature Stress

2.7. Stability of Bacteriophages in Surfactants and Organic Solvents

2.8. Glass-Based Container Surfaces Disinfection Assay

2.9. Evaluation of Anti-Biofilm Activity

2.10. Agar-Based Phage Infection Assay with Time-Resolved CFU Enumeration

2.11. Bacterial DNA Extraction and Genome Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Phenotypic Characterization of Staphylococcus Host Strains

3.2. Environmental Isolation and Detection of Staphylococcus-Infecting Bacteriophages

3.3. Host Range of Isolated Bacteriophages Against Clinical S. aureus Isolates

3.4. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Bacteriophages MRSA-W3 and SA-W2

3.5. Thermal Stability of Bacteriophages MRSA-W3 and SA-W2

3.6. Time-Resolved Bacterial Viability During Phage Infection

3.7. Compatibility of Bacteriophages with Organic Solvents and Surfactants

3.8. Surface Disinfection Efficacy of Phage–Surfactant Formulations

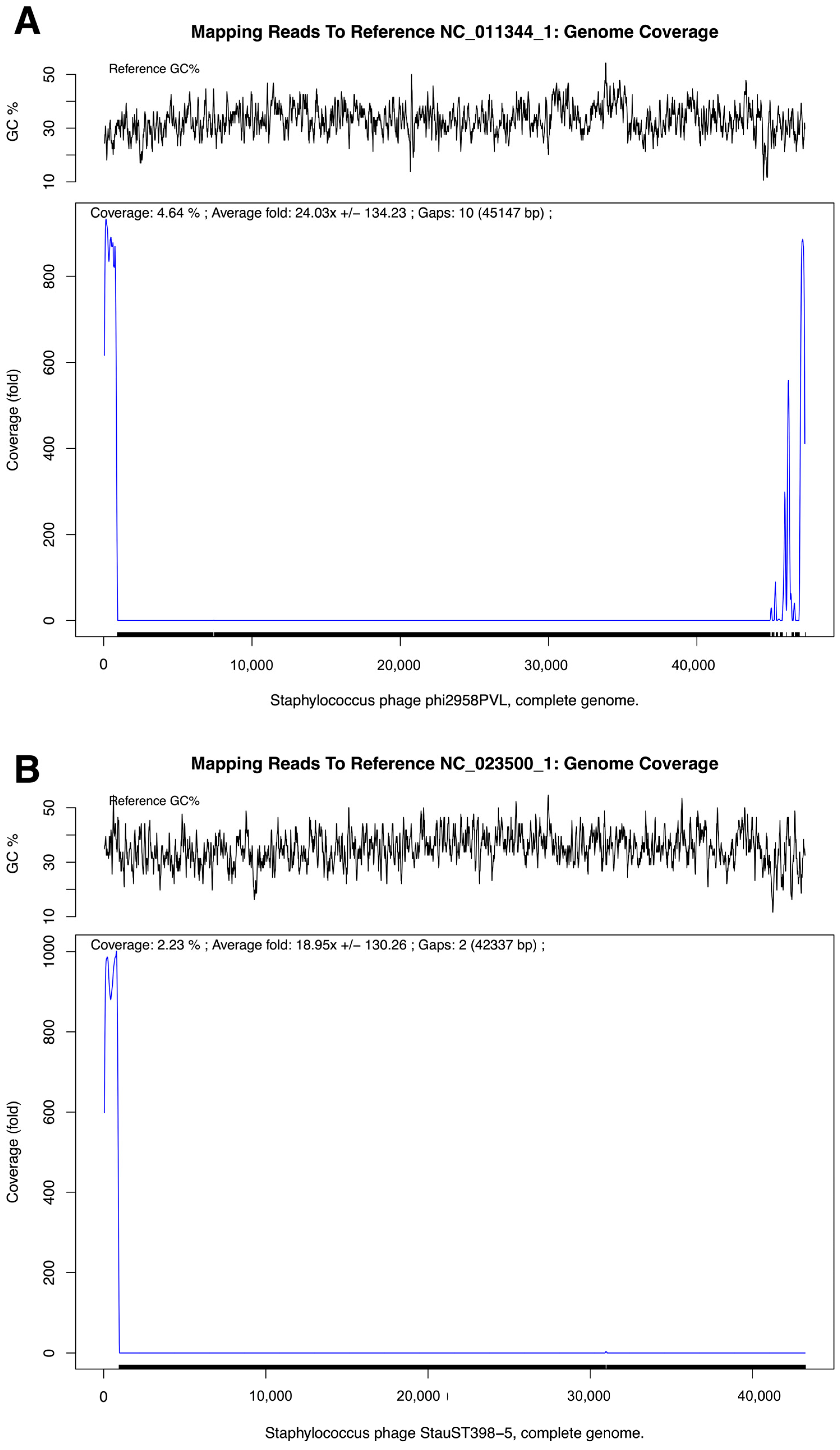

3.9. Genome Assembly and Taxonomic Profiling of MRSA-Infecting Phage MRSA-W3

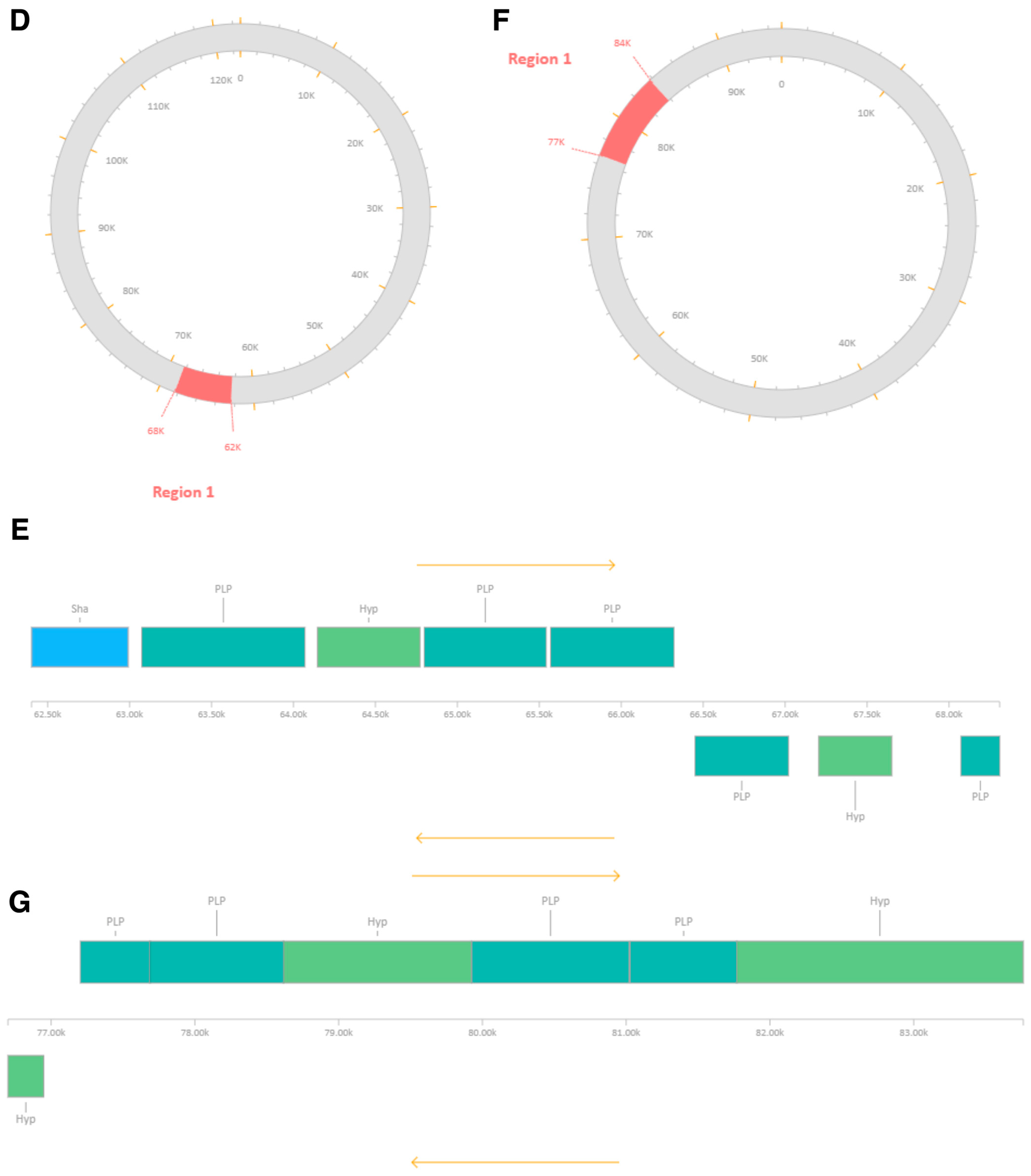

3.10. Prophage-like Region and Genomic Relatedness of the MRSA-Infecting Phage MRSA-W3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turner, N.A.; Sharma-Kuinkel, B.K.; Maskarinec, S.A.; Eichenberger, E.M.; Shah, P.P.; Carugati, M.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G., Jr. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An overview of basic and clinical research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtis, A.P.; Hatfield, K.; Baggs, J.; Mu, Y.; See, I.; Epson, E.; Nadle, J.; Kainer, M.A.; Dumyati, G.; Petit, S.; et al. Vital Signs: Epidemiology and Recent Trends in Methicillin-Resistant and in Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infections—United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, M. Staphylococcal biofilms. In Bacterial Biofilms; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulgeraki, A.I.; Efthimiou, G.; Paramithiotis, S.; Pappas, K.M.; Typas, M.A.; Nychas, G.J. Effect of rocket (Eruca sativa) extract on MRSA growth and proteome: Metabolic adjustments in plant-based media. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledwoch, K.; Said, J.; Norville, P.; Maillard, J.Y. Artificial dry surface biofilm models for testing the efficacy of cleaning and disinfection. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancer, S.J. Reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission in hospitals: Focus on additional infection control strategies. Surgery 2021, 39, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.J.; Sickbert-Bennett, E.E.; Dibiase, L.M.; Brewer, B.E.; Buchanan, M.O.; Clark, C.A.; Croyle, K.; Culbreth, C.M.; Del Monte, P.S.; Goldbach, S.; et al. A new paradigm for infection prevention programs: An integrated approach. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G.; Todt, D.; Pfaender, S.; Steinmann, E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wand, M.E.; Bock, L.J.; Bonney, L.C.; Sutton, J.M. Mechanisms of increased resistance to chlorhexidine and cross-resistance to colistin following exposure of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates to chlorhexidine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01162-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, J.Y. Bacterial resistance to biocides in the healthcare environment: Should it be of genuine concern? J. Hosp. Infect. 2007, 65, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, J.-Y. Antimicrobial biocides in the healthcare environment: Efficacy, usage, policies, and perceived problems. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2005, 1, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Strategy on Infection Prevention and Control. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, e477–e479. [Google Scholar]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Verbeken, G.; Ceyssens, P.J.; Huys, I.; de Vos, D.; Ameloot, C.; Fauconnier, A. The magistral phage. Viruses 2018, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Use of phage therapy to treat long-standing, persistent, or chronic bacterial infections. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 145, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortright, K.E.; Chan, B.K.; Koff, J.L.; Turner, P.E. Phage Therapy: A Renewed Approach to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaczek, M.; Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Weber-Dabrowska, B.; Miedzybrodzki, R.; Owczarek, B.; Kopciuch, A.; Fortuna, W.; Rogóż, P.; Górski, A. Antibody production in response to staphylococcal MS-1 phage cocktail in patients undergoing phage therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Zaczek, M.; Weber-Dabrowska, B.; Miȩdzybrodzki, R.; Kłak, M.; Fortuna, W.; Letkiewicz, S.; Rogóż, P.; Szufnarowski, K.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; et al. Phage neutralization by sera of patients receiving phage therapy. Viral Immunol. 2014, 27, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.R.; Parracho, H.M.R.T.; Walker, J.; Sharp, R.; Hughes, G.; Werthén, M.; Lehman, S.; Morales, S. Bacteriophages and biofilms. Antibiotics 2014, 3, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.P.; Melo, L.D.R.; Vilas Boas, D.; Sillankorva, S.; Azeredo, J. Phage therapy as an alternative or complementary strategy to prevent and control biofilm-related infections. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 39, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.P.; Costa, A.R.; Pinto, G.; Meneses, L.; Azeredo, J. Current challenges and future opportunities of phage therapy. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, O.; Jewel, Z.A.; Bairagi, S.; Rasheduzzaman, M.; Bagchi, H.; Tuha, A.S.M.; Hossain, I.; Bala, A.; Ali, S. Phage treatment of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in humans, animals, and plants: The current status and future prospects. Infect. Med. 2025, 4, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clokie, M.R.J.; Millard, A.D.; Letarov, A.V.; Heaphy, S. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowah, A.S.A.; Clokie, M.R.J. Review of the nature, diversity and structure of bacteriophage receptor binding proteins that target Gram-positive bacteria. Biophys. Rev. 2018, 10, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, R.M.; Guerrero-Bustamante, C.A.; Garlena, R.A.; Russell, D.A.; Ford, K.; Harris, K.; Gilmour, K.C.; Soothill, J.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Schooley, R.T.; et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casjens, S. Prophages and bacterial genomics: What have we learned so far? Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 49, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, W.H.; Augustine, D.A.; Carroll, D.C.; Duncan, J.C.; Harwi, K.M.; Howry, R.; Jagessar, B.; Lum, B.A.; Meinert, J.W.; Migliozzi, J.S.; et al. Genome sequences of cluster G mycobacteriophages Cambiare, FlagStaff, and MOOREtheMARYer. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00595-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.Y.C.; Davis, J.S.; Eichenberger, E.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G. Staphylococcus aureus infections: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 603–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P.; Abedon, S.T. Practical methods for determining phage growth parameters. In Bacteriophages; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, P. Phages for phage therapy: Isolation, characterization, and host range breadth. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Ruan, H.; Chen, L.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wu, R.; Sun, D. Potential of bacteriophages as disinfectants to control of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, D.J.; Sokolov, I.J.; Vinner, G.K.; Mancuso, F.; Cinquerrui, S.; Vladisavljevic, G.T.; Clokie, M.R.J.; Garton, N.J.; Stapley, A.G.F.; Kirpichnikova, A. Formulation, stabilisation and encapsulation of bacteriophage for phage therapy. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 249, 100–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, A.J.; Askew, P.D.; Stephan, I.; Iredale, G.; Cosemans, P.; Simmons, L.M.; Verran, J.; Redfern, J. How do we determine the efficacy of an antibacterial surface? A review of standardised antibacterial material testing methods. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y.E.; Weyandt, R.; Dewald, W.; Tolksdorf, T.; Müller, L.; Braun, A. A realistic approach for evaluating antimicrobial surfaces for dry surface exposure scenarios. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0115024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwamahoro, M.C.; Massicotte, R.; Hurtubise, Y.; Gagné-Bourque, F.; Mafu, A.A.; Yahia, L. Evaluating the Sporicidal Activity of Disinfectants against Clostridium difficile and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Spores by Using the Improved Methods Based on ASTM E2197-11. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesgate, R.; Robertson, A.; Barrell, M.; Teska, P.; Maillard, J.Y. Impact of test protocols and material binding on the efficacy of antimicrobial wipes. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 103, e25–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, M.K.; Dobariya, B.; Heidkamp, H.; Ade, C.; Flemming, H.C.; Bockmühl, D.P. How Effective Are Cleaners With “Effective Microorganisms”? J. Surfactants Deterg. 2025, 28, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsches Institut für Normung e. V. DIN EN 13697. Beuth Verlag 2015. Available online: https://microbe-investigations.com/disinfectant-testing/disinfectant-antibacterial/en-13697-bactericidal-fungicidal-yeasticidal-activity-test-for-disinfectants/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Crivello, G.; Fracchia, L.; Ciardelli, G.; Boffito, M.; Mattu, C. In Vitro Models of Bacterial Biofilms: Innovative Tools to Improve Understanding and Treatment of Infections. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopjitt, P.; Tangthong, P.; Kongkaem, J.; Wonkyai, P.; Charoenwattanamaneechai, A.; Khankhum, S.; Sunthamala, P.; Kerdsin, A.; Sunthamala, N. Molecular characterization and genotype of multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis in nasal carriage of young population, Mahasarakham, Thailand. Biomol. Biomed. 2025, 25, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntová, L.; Mašlanová, I.; Oborilová, R.; Šimecková, H.; Finstrlová, A.; Bárdy, P.; Šiborová, M.; Troianovska, L.; Botka, T.; Gintar, P.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus Prophage-Encoded Protein Causes Abortive Infection and Provides Population Immunity against Kayviruses. MBio 2023, 14, e0249022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.H.; Adelskov, J.; Greene, A.C. Bacterial DNA Extraction Using Individual Enzymes and Phenol/Chloroform Separation. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2017, 18, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbeek, R.; Begley, T.; Butler, R.M.; Choudhuri, J.V.; Chuang, H.Y.; Cohoon, M.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Diaz, N.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.; et al. The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 5691–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, D.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: Hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis—10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D694–D697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Han, B.C.; Kumar, P.; Liu, X.H.; Ma, X.H.; Wei, X.N.; Huang, L.; Guo, Y.; Han, L.; Zheng, C.; et al. Update of TTD: Therapeutic Target Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 38, D787–D791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, A.G.; Waglechner, N.; Nizam, F.; Yan, A.; Azad, M.A.; Baylay, A.J.; Bhullar, K.; Canova, M.J.; De Pascale, G.; Ejim, L.; et al. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3348–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ondov, B.D.; Treangen, T.J.; Melsted, P.; Mallonee, A.B.; Bergman, N.H.; Koren, S.; Phillippy, A.M. Mash: Fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.J.; Gerdes, S.; Olsen, G.J.; Olson, R.; Pusch, G.D.; Shukla, M.; Vonstein, V.; Wattam, A.R.; Yoo, H. PATtyFams: Protein families for the microbial genomes in the PATRIC database. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A.; Hoover, P.; Rougemont, J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 2008, 57, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Xu, M.; Gu, J. AfterQC: Automatic filtering, trimming, error removing and quality control for fastq data. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikheenko, A.; Prjibelski, A.; Saveliev, V.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A. Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i142–i150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florensa, A.F.; Kaas, R.S.; Clausen, P.T.L.C.; Aytan-Aktug, D.; Aarestrup, F.M. ResFinder—An open online resource for identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next-generation sequencing data and prediction of phenotypes from genotypes. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medema, M.H.; Blin, K.; Cimermancic, P.; De Jager, V.; Zakrzewski, P.; Fischbach, M.A.; Weber, T.; Takano, E.; Breitling, R. AntiSMASH: Rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W339–W346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Dong, Z.; Fang, L.; Luo, Y.; Wei, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhang, G.; Gu, Y.Q.; Coleman-Derr, D.; Xia, Q.; et al. OrthoVenn2: A web server for whole-genome comparison and annotation of orthologous clusters across multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W52–W58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, D.; Grant, J.R.; Marcu, A.; Sajed, T.; Pon, A.; Liang, Y.; Wishart, D.S. PHASTER: A better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W16–W21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liang, Y.; Lynch, K.H.; Dennis, J.J.; Wishart, D.S. PHAST: A Fast Phage Search Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W347–W352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasak, A.M.; Zaman, Q.; Pfeiffer, K.P.; Göbel, G.; Ulmer, H. Statistical errors in medical research—A review of common pitfalls. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2007, 137, 44–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareschi, A.; Gaglio, S.C.; Dervishi, K.; Minoia, A.; Zanella, G.; Lucchi, L.; Serena, E.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Piritore, F.C.; Meneghel, M.; et al. Evaluation of Biocontrol Measures to Reduce Bacterial Load and Healthcare-Associated Infections. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guentzel, J.L.; Liang Lam, K.; Callan, M.A.; Emmons, S.A.; Dunham, V.L. Reduction of bacteria on spinach, lettuce, and surfaces in food service areas using neutral electrolyzed oxidizing water. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, M.; Bastías, R. Virulence reduction in bacteriophage resistant bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yin, R.; Cheng, J.; Lin, J. Bacterial Biofilm Formation on Biomaterials and Approaches to Its Treatment and Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S. Phage Therapy Pharmacology. Calculating Phage Dosing. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Verma, N.; Kumar, V.; Apoorva, P.; Agarwal, V. Biofilm inhibition/eradication: Exploring strategies and confronting challenges in combatting biofilm. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A. Emerging roles of bacteriophage-based therapeutics in combating antibiotic resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1384164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E.M.; Gorman, S.P.; Donnelly, R.F.; Gilmore, B.F. Recent advances in bacteriophage therapy: How delivery routes, formulation, concentration and timing influence the success of phage therapy. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 63, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, J.M. Modern technologies for improving cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces in hospitals. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2016, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, H.G.; Watson, B.N.J.; Fineran, P.C. The arms race between bacteria and their phage foes. Nature 2020, 577, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieft, K.; Zhou, Z.; Anantharaman, K. VIBRANT: Automated recovery, annotation and curation of microbial viruses, and evaluation of viral community function from genomic sequences. Microbiome 2020, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, T.; Liu, J.; DuBow, M.; Gros, P.; Pelletier, J. The complete genomes and proteomes of 27 Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5174–5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vill, A.C.; Delesalle, V.A.; Tomko, B.E.; Lichty, K.B.; Strine, M.S.; Guffey, A.A.; Burton, E.A.; Tanke, N.T.; Krukonis, G.P. Comparative Genomics of Six Lytic Bacillus subtilis Phages from the Southwest United States. PHAGE Ther. Appl. Res. 2022, 3, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Verbeken, G. Magistral Phage Preparations: Is This the Model for Everyone? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, S360–S369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, M.; Ferry, T.; Khan Mirzaei, M.; Alt, V.; Deng, L.; Walter, N. Bacteriophages for the treatment of musculoskeletal infections—An overview of clinical use, open questions, and legal framework. Orthopadie 2025, 54, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabijan, A.P.; Iredell, J.; Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Kebriaei, R.; Abedon, S.T. Translating phage therapy into the clinic: Recent accomplishments but continuing challenges. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Bagchi, D.; Chen, I.A. Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution of Phages and their Current Applications in Antimicrobial Therapy. Adv. Ther. 2024, 7, 2300355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Sample Type | Sampling Location | Geographic Coordinates (Lat, Long) | S. epidermidis TISTR 518 | MRSA S. aureus DMST 20654 | S. aureus TISTR 746 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Soil | Cattle shed, Lam Chi area | 16.220521, 103.274104 | + | + | + |

| S2 | Soil | Rear area of cattle shed, Lam Chi | 16.220521, 103.274104 | + | + | + |

| S3 | Soil | Cattle shed, village area | 16.248027, 103.257684 | − | + | + |

| S4 | Soil | Pond side near cattle shed, village | 16.248027, 103.257684 | − | + | + |

| S5 | Soil | Pond side, front of Mahasarakham University | 16.247221, 103.256828 | − | + | + |

| W1 | Water | Water in front of cattle shed, Lam Chi | 16.220521, 103.274104 | − | + | + |

| W2 | Water | Water behind cattle shed, Lam Chi | 16.220521, 103.274104 | + | + | + |

| W3 | Water | Water within cattle shed, village | 16.248027, 103.257684 | − | + | + |

| W4 | Water | Pond water near cattle shed, village | 16.248027, 103.257684 | − | + | + |

| W5 | Water | Wastewater from public park, Mahasarakham University | 16.247221, 103.256828 | − | + | + |

| Phage Isolate | Susceptible/Tested | Host Range (%) | 95% CI (Wilson) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical S. aureus isolates (n = 50) | |||

| MRSA-S1 | 20/50 | 40.0 | 27.6–53.8 |

| MRSA-S2 | 25/50 | 50.0 | 36.8–63.2 |

| MRSA-W3 | 39/50 | 78.0 | 64.8–87.3 |

| SA-S1 | 14/50 | 28.0 | 17.2–41.6 |

| SA-S2 | 24/50 | 48.0 | 35.0–61.3 |

| SA-W1 | 22/50 | 44.0 | 31.4–57.4 |

| SA-W2 | 29/50 | 58.0 | 44.2–70.7 |

| SA-W5 | 18/50 | 36.0 | 24.3–49.6 |

| SE-W2 | 17/50 | 34.0 | 22.5–47.5 |

| Non-Staphylococcus strains (n = 7) | |||

| MRSA-W3 | 5/7 | 71.4 | 35.9–91.8 |

| SA-W2 | 5/7 | 71.4 | 35.9–91.8 |

| Other phages | 0/7 | 0.0 | 0.0–35.4 |

| Bacteriophage | Temperature Range (°C) | Stability Classification | Evidence from Plaque Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA-W3 | 25 | Stable | Plaques detected at all exposure times with countable plaques up to 104 PFU/mL |

| 37 | Stable | Confluent plaques observed at all dilutions and time points | |

| 50 | Stable | Plaques consistently detected across all dilutions and exposure times | |

| 60 | Stable | No loss of plaque-forming ability at any dilution or time point | |

| SA-W2 | 25 | Stable | Plaques observed at all phage concentrations (109–104 PFU/mL) and exposure times |

| 37 | Partially stable | Loss of plaques at 104 PFU/mL across all time points | |

| 50 | Stable | Plaques retained at all dilutions and exposure times | |

| 60 | Stable | Detectable plaques maintained, including high dilutions at prolonged exposure |

| Rank | Solvent/Surfactant | Overall Suitability | Scientific Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SDS | Highly suitable | Consistent clear lysis (C) indicates maximal lytic activity; ideal for surface disinfection where rapid killing is desired |

| 2 | Triton X-100 | Highly suitable | Strong clear lysis for SA-W2 and stable plaques for MRSA-W3; effective non-ionic surfactant |

| 3 | Tween 80 | Suitable | Maintains plaque-forming activity without suppressing infectivity; formulation-friendly |

| 4 | DMSO | Conditionally suitable | Supports activity at low–moderate concentrations; not ideal at high levels |

| 5 | Ethanol (EtOH) | Limited suitability | Rapid loss of activity at ≥10% limits disinfectant applications |

| Phage/Strain | Treatment | Time (min) | CFU | log10 CFU | Δlog10 Reduction vs. Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA-W3 | Control (no treatment) | 2 | 300 | 2.48 | – |

| 5 | 300 | 2.48 | – | ||

| 10 | 300 | 2.48 | – | ||

| 15 | 300 | 2.48 | – | ||

| 20 | 248 | 2.40 | – | ||

| MRSA-W3 | MRSA-W3 + 1% Triton X-100 + 1% SDS (10−3) | 2 | 47 | 1.67 | 0.81 |

| 5 | 12 | 1.08 | 1.40 | ||

| 10 | 15 | 1.18 | 1.30 | ||

| 15 | 2 | 0.30 | 2.18 | ||

| 20 | 3 | 0.48 | 1.92 | ||

| SA-W2 | Control (no treatment) | 2 | 16 | 1.20 | – |

| 5 | 41 | 1.61 | – | ||

| 10 | 5 | 0.70 | – | ||

| 15 | 0 * | 0.00 | – | ||

| 20 | 2 | 0.30 | – | ||

| SA-W2 | SA-W2 + 1% Triton X-100 + 1% SDS (10−3) | 2 | 71 | 1.85 | −0.65 |

| 5 | 210 | 2.32 | −0.71 | ||

| 10 | 7 | 0.85 | −0.15 | ||

| 15 | 8 | 0.90 | −0.90 | ||

| 20 | 3 | 0.48 | −0.18 |

| Tool | Database/Algorithm | Reads | % Reads | Taxonomic Level | Top 1 Hit | Top 2 Hit | Top 3 Hit | Top 4 Hit | Top 5 Hit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOTTCHA (Bacteria) | gottcha-strDB-b | 547,027 | 63.5 | Strain | S. aureus MSHR1132 | S. aureus MRSA252 | S. warneri SG1 | S. aureus CN1 | S. aureus JKD6159 |

| GOTTCHA (Virus) | gottcha-strDB-v | 762 | 0.1 | Strain | Staphylococcus phage StauST398-5 | Staphylococcus phage phi2958PVL | Staphylococcus phage phiPVL-CN125 | Staphylococcus phage PT1028 | Staphylococcus phage 42e |

| PANGIA | k-mer + alignment | 264,927 | 30.8 | Strain | S. aureus JKD6159 | S. aureus M1169 | S. aureus NCTC8325 | S. aureus NCTC8726 | S. aureus NCTC5663 |

| MetaPhlAn4 | Marker gene-based | 0 | 0.0 | Strain | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| BWA | Read mapping | 130,864 | 15.2 | Strain | S. aureus JKD6159 | S. aureus MSSA476 | S. aureus MRSA252 | S. aureus USA300 | S. aureus ST398 |

| Kraken2 | k-mer classification | 11,344 | 1.3 | Strain | S. aureus JKD6159 | Unclassified Staphylococcus | S. aureus TCH60 | S. aureus ST398 | S. epidermidis PM221 |

| Centrifuge | Index-based classification | 1701 | 0.2 | Strain | S. aureus JKD6159 | S. epidermidis PM221 | S. aureus T0131 | S. aureus ST398 | S. aureus JKD6159 |

| DIAMOND | Protein alignment | 0 | 0.0 | Strain | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Taxonomic Level | Viral Species | Read Count | Relative Abundance (%) | Plasmid-Associated Reads (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Staphylococcus phage StauST398-5 | 274 | 59.1 | 0.0 |

| Species | Staphylococcus phage phi2958PVL | 150 | 30.3 | 0.0 |

| Species | Staphylococcus phage phiPVL-CN125 | 52 | 7.4 | 0.0 |

| Species | Staphylococcus phage PT1028 | 233 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| Species | Staphylococcus phage 42e | 77 | 1.4 | 0.0 |

| Species | Zaire ebolavirus | 3 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Contig | Prophage Like Region | Genomic Position (bp) | Region Length (kb) | Completeness | Prophage Score | No. of CDSs | Closest Related Phage | GC Content (%) | Key Genetic Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA-W3_001 | Region 1 | 90,867–97,938 | ~7.0 | Incomplete | 20 | 8 | Staphylococcus phage SA97 (NC_029010) | 27.23 | Capsid proteins, scaffold protein, DNA-binding protein |

| MRSA-W3_001 | Region 2 | 209,791–219,168 | ~9.3 | Incomplete | 20 | 13 | Staphylococcus phage SPβ-like (NC_029119) | 31.69 | Integrase, terminase, tail-associated proteins, nucleotide metabolism enzymes |

| MRSA-W3_007 | Region 1 | 62,402–68,309 | ~5.9 | Incomplete | 20 | 8 | Staphylococcus phage phiSa119 (NC_025460) | 29.77 | Structural proteins, holin, enterotoxin/exotoxin-related genes |

| MRSA-W3_009 | Region 1 | 76,700–83,762 | ~7.0 | Incomplete | 10 | 7 | Planktophage PaV-LD (NC_016564) | 33.16 | Metabolic/regulatory proteins; mosaic phage signatures |

| Reference Phage | Accession No. | Genome Length (bp) | GC Content (%) | Mapped Reads (n) | Reads (%) | Average Coverage (×) | Gaps (n) | SNVs | INDELs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus phage phi2958PVL | NC_011344.1 | 47,342 | 33.04 | 9591 | 0.04 | 24.03 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Staphylococcus phage StauST398-5 | NC_023500.1 | 43,301 | 35.14 | 5598 | 0.02 | 18.95 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chopjitt, P.; Kanha, W.; Sachit, A.; Thongkam, J.; Kanthain, P.; Pradabsri, P.; Paiboon, S.; Thananchai, S.; Khankhum, S.; Kerdsin, A.; et al. Bacteriophage-Based Control of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Anti-Biofilm Activity, Surface-Active Formulation Compatibility, and Genomic Context. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15020155

Chopjitt P, Kanha W, Sachit A, Thongkam J, Kanthain P, Pradabsri P, Paiboon S, Thananchai S, Khankhum S, Kerdsin A, et al. Bacteriophage-Based Control of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Anti-Biofilm Activity, Surface-Active Formulation Compatibility, and Genomic Context. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(2):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15020155

Chicago/Turabian StyleChopjitt, Peechanika, Wanwisa Kanha, Achiraya Sachit, Juthamas Thongkam, Phinkan Kanthain, Pornnapa Pradabsri, Supreeya Paiboon, Sirinan Thananchai, Surasak Khankhum, Anusak Kerdsin, and et al. 2026. "Bacteriophage-Based Control of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Anti-Biofilm Activity, Surface-Active Formulation Compatibility, and Genomic Context" Antibiotics 15, no. 2: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15020155

APA StyleChopjitt, P., Kanha, W., Sachit, A., Thongkam, J., Kanthain, P., Pradabsri, P., Paiboon, S., Thananchai, S., Khankhum, S., Kerdsin, A., & Sunthamala, N. (2026). Bacteriophage-Based Control of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Anti-Biofilm Activity, Surface-Active Formulation Compatibility, and Genomic Context. Antibiotics, 15(2), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15020155