Genomic Surveillance of 3R Genes Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

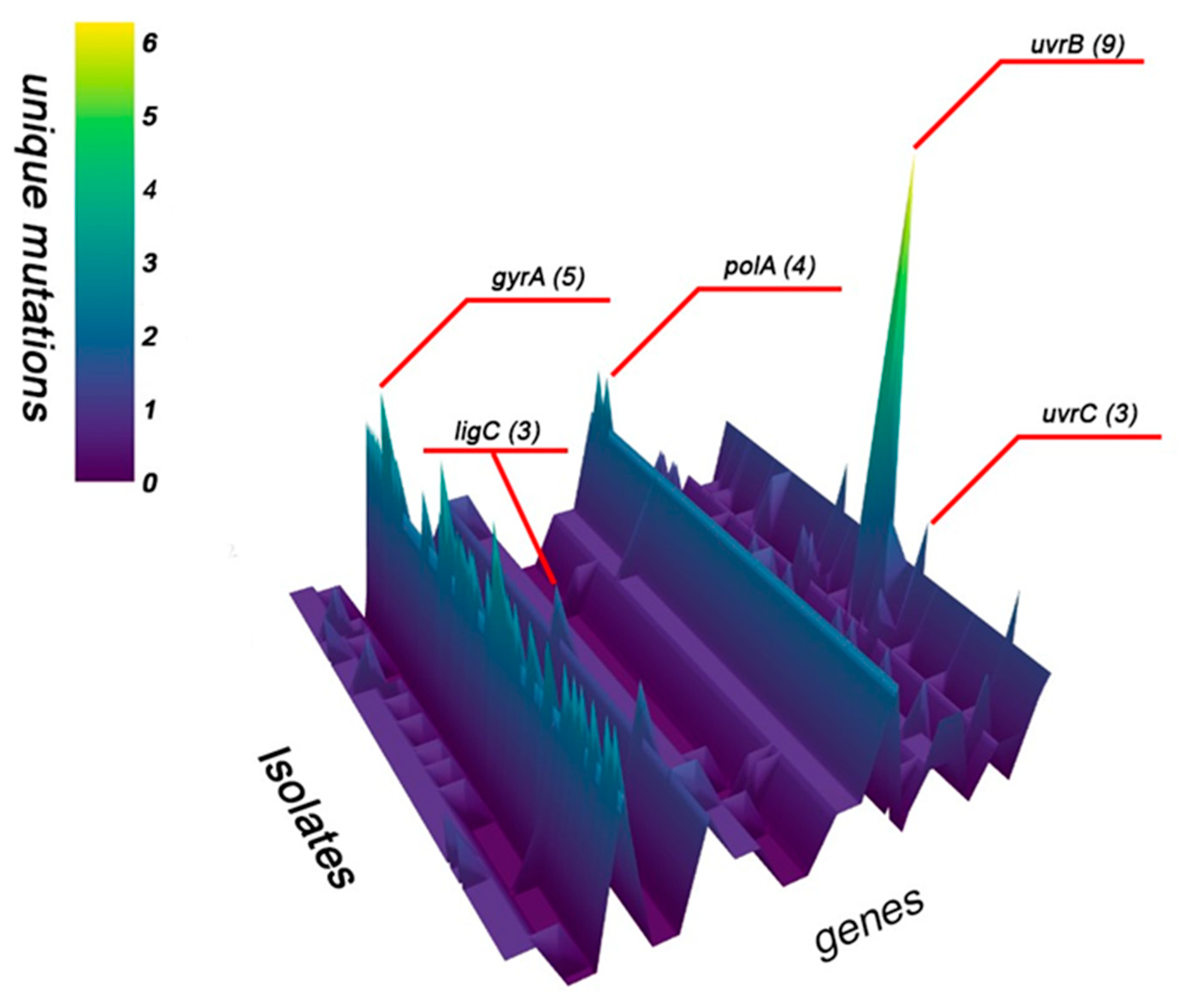

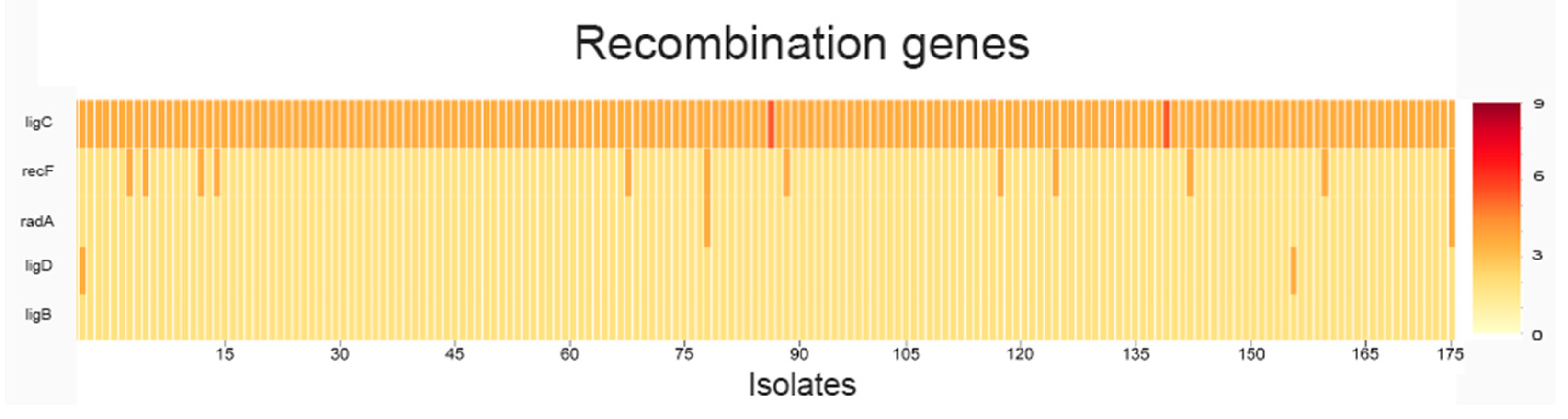

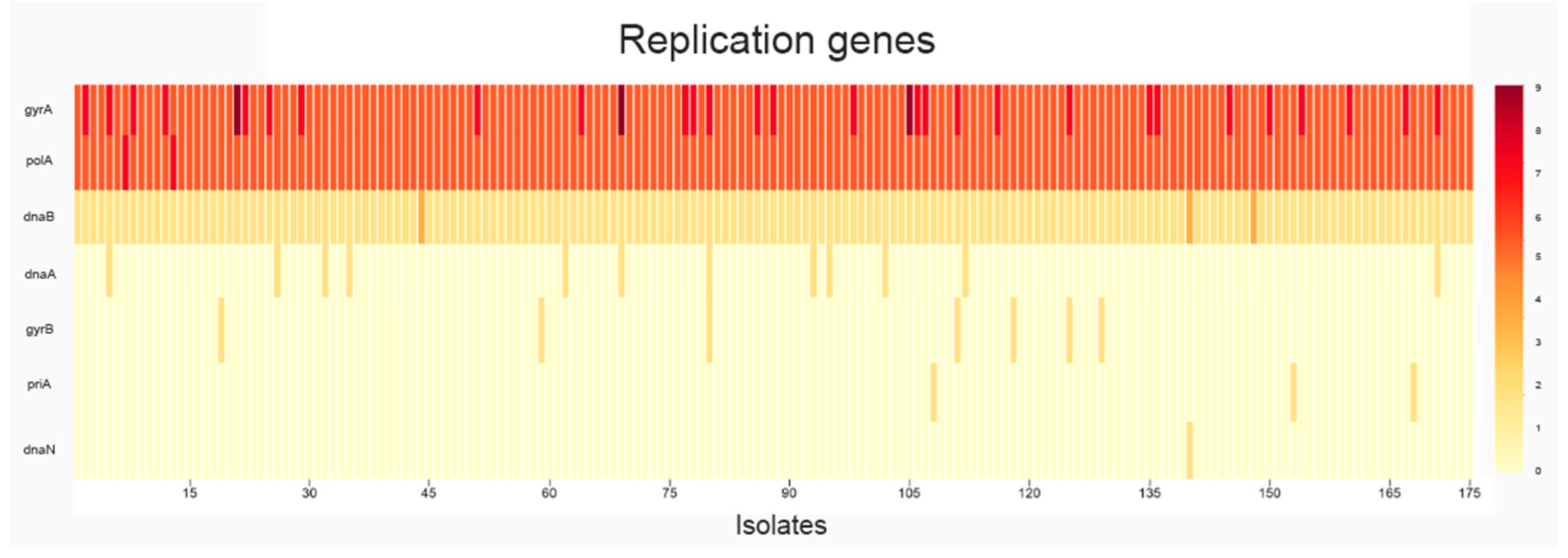

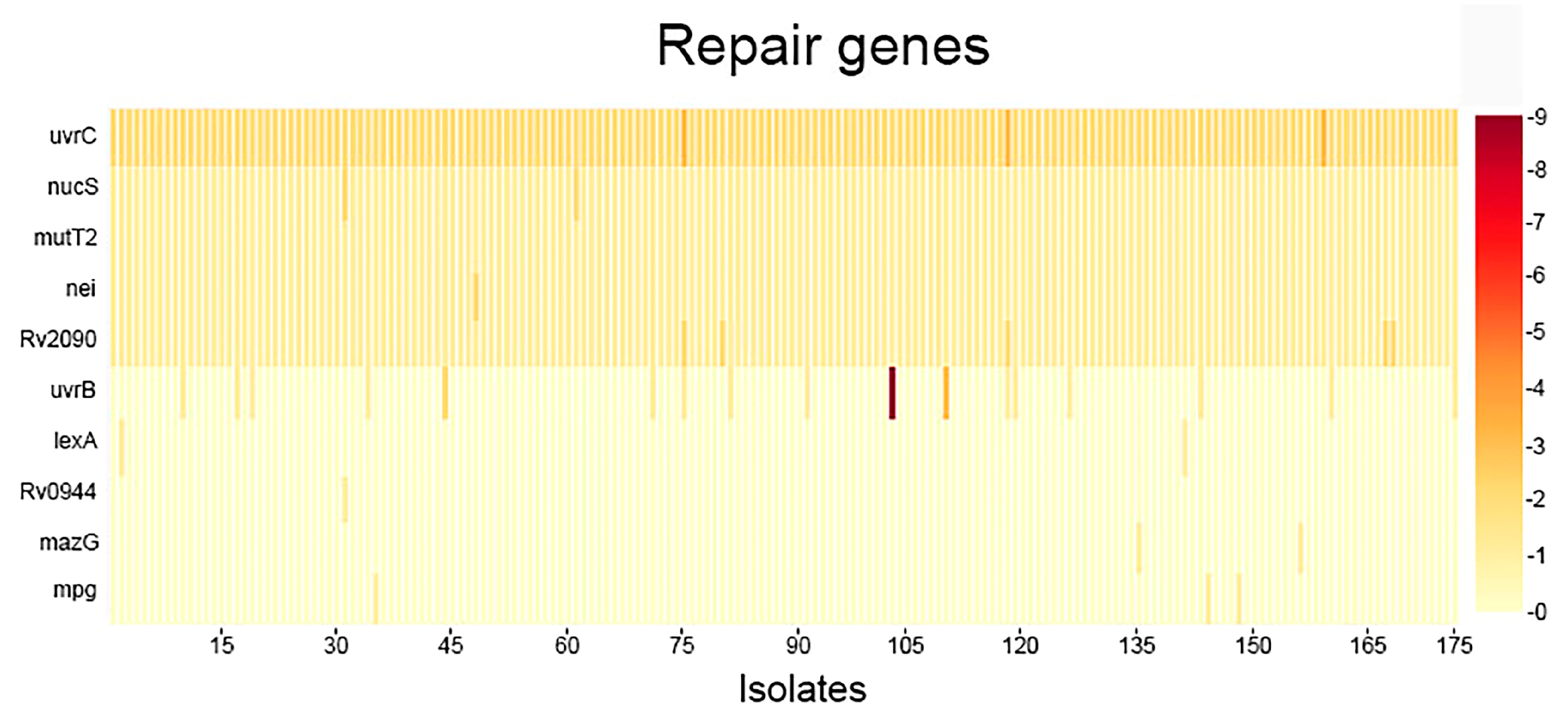

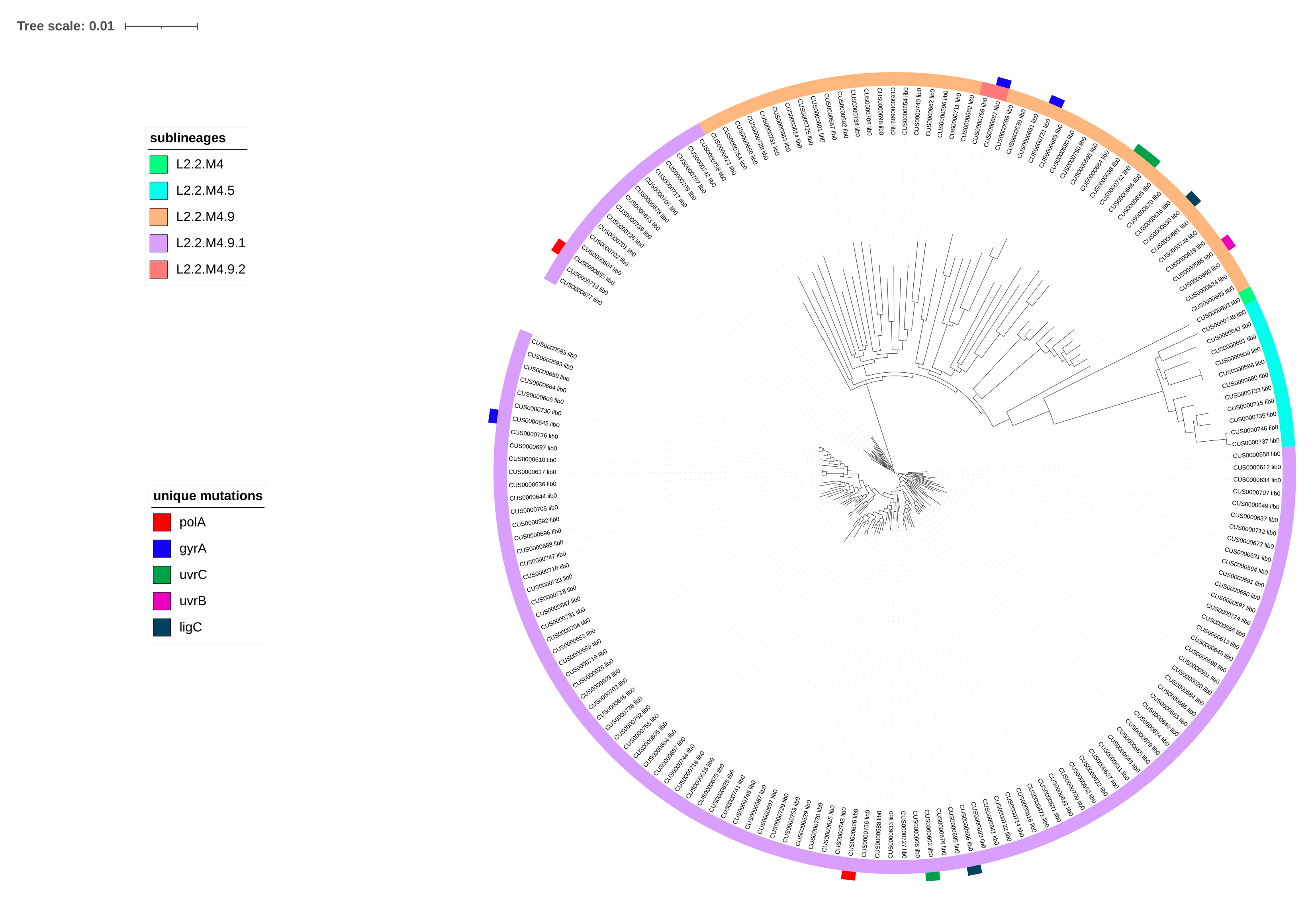

2.1. Analysis of SNPs

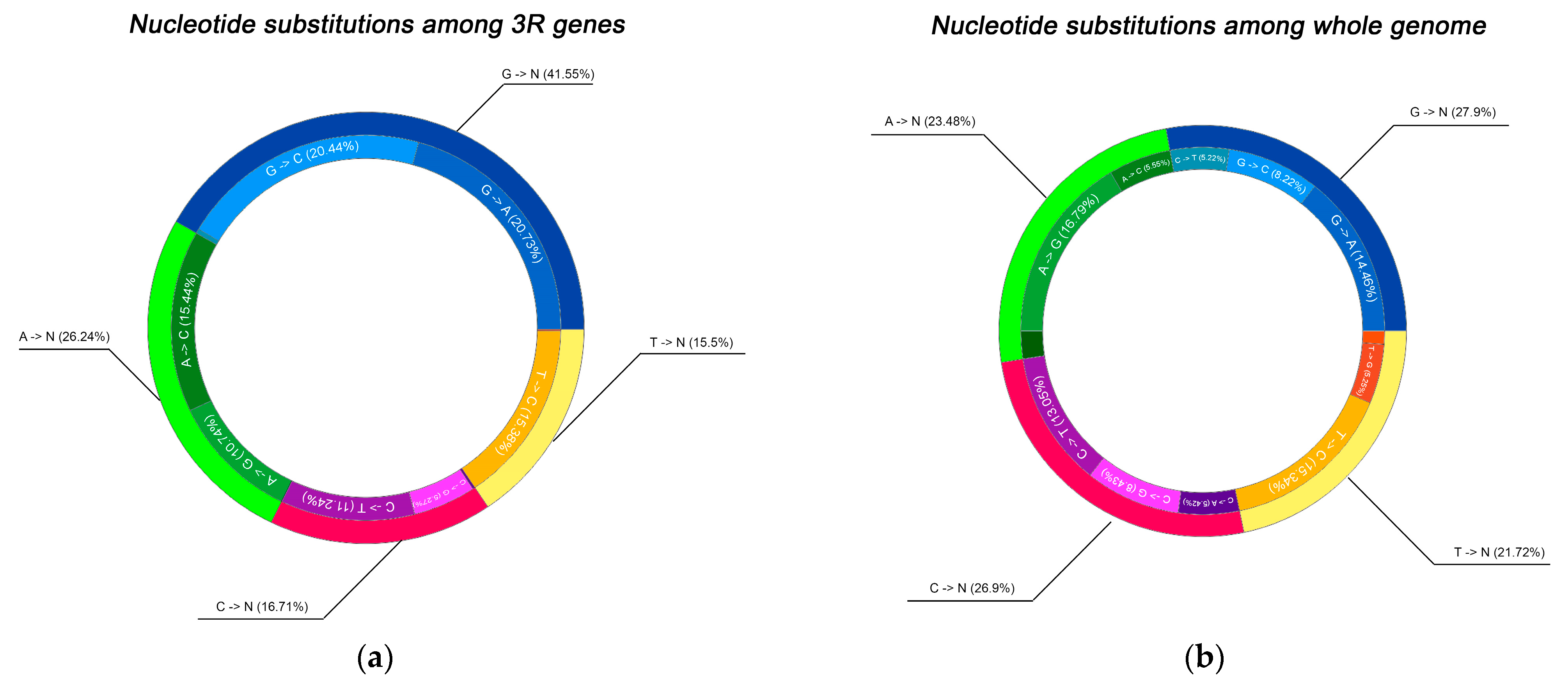

2.2. Spectrum of Nucleotide Substitutions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source

4.2. Genomic Data Processing

4.3. Local Gene Database Construction

4.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.5. Visualization and Statistical Interpretation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bagcchi, S. WHO’s Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.S.; Tosas Auguet, O.; Glaziou, P.; Zignol, M.; Ismail, N.; Kasaeva, T.; Floyd, K. 25 years of surveillance of drug-resistant tuberculosis: Achievements, challenges, and way forward. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e191–e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhmetova, A.; Bismilda, V.; Chingissova, L.; Filipenko, M.; Akilzhanova, A.; Kozhamkulov, U. Prevalence of Beijing Central Asian/Russian Cluster 94–32 among Multidrug-Resistant M. tuberculosis in Kazakhstan. Antibiotics 2023, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Lists of High Burden Countries for TB, Multidrug/Rifampicin-Resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB) and TB/HIV, 2021–2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Auganova, D.; Atavliyeva, S.; Gharbi, N.; Zholdybayeva, E.; Skiba, Y.; Akisheva, A.; Tsepke, A.; Alenova, A.; Guyeux, C.; Wirth, T.; et al. Genomic characterization and epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage 2 isolates from Kazakhstan. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atavliyeva, S.; Auganova, D.; Tarlykov, P. Genetic diversity, evolution and drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage 2. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1384791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hof, S.; Collins, D.; Hafidz, F.; Beyene, D.; Tursynbayeva, A.; Tiemersma, E. The socioeconomic impact of multidrug resistant tuberculosis on patients: Results from Ethiopia, Indonesia and Kazakhstan. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhamkulov, U.; Iglikova, S.; Rakisheva, A.; Almazan, J. Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Central Asia and Predominant Beijing Lineage, Challenges in Diagnosis, Treatment Barriers, and Infection Control Strategies: An Integrative Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, C.B.; Shah, R.R.; Maeda, M.K.; Gagneux, S.; Murray, M.B.; Cohen, T.; Johnston, J.C.; Gardy, J.; Lipsitch, M.; Fortune, S.M. Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutation rate estimates from different lineages predict substantial differences in the emergence of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, K.A.; Manson, A.L.; Desjardins, C.A.; Abeel, T.; Earl, A.M. Deciphering drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis using whole-genome sequencing: Progress, promise, and challenges. Genome Med. 2019, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, M.; Gey van Pittius, N.C.; van Helden, P.D.; Warren, R.M.; Warner, D.F. Mutation rate and the emergence of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkey, J.; Wyres, K.L.; Judd, L.M.; Harshegyi, T.; Blakeway, L.; Wick, R.R.; Jenney, A.W.J.; Holt, K.E. ESBL plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae: Diversity, transmission and contribution to infection burden in the hospital setting. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneux, S. Ecology and evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, K.A.; Abeel, T.; Manson McGuire, A.; Desjardins, C.A.; Munsamy, V.; Shea, T.P.; Walker, B.J.; Bantubani, N.; Almeida, D.V.; Alvarado, L.; et al. Evolution of Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis over Four Decades: Whole Genome Sequencing and Dating Analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from KwaZulu-Natal. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belay, W.Y.; Getachew, M.; Tegegne, B.A.; Teffera, Z.H.; Dagne, A.; Zeleke, T.K.; Abebe, R.B.; Gedif, A.A.; Fenta, A.; Yirdaw, G.; et al. Mechanism of antibacterial resistance, strategies and next-generation antimicrobials to contain antimicrobial resistance: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1444781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, A.L.; Cohen, K.A.; Abeel, T.; Desjardins, C.A.; Armstrong, D.T.; Barry, C.E., 3rd; Brand, J.; Chapman, S.B.; Cho, S.N.; Gabrielian, A.; et al. Genomic analysis of globally diverse Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains provides insights into the emergence and spread of multidrug resistance. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.M.; Kohl, T.A.; Omar, S.V.; Hedge, J.; Del Ojo Elias, C.; Bradley, P.; Iqbal, Z.; Feuerriegel, S.; Niehaus, K.E.; Wilson, D.J.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing for prediction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug susceptibility and resistance: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A data compendium associating the genomes of 12,289 Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with quantitative resistance phenotypes to 13 antibiotics. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001721. [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Paritosh, K.; Sanyal, P.; Khan, S.; Singh, Y.; Varshney, U.; Nandicoori, V.K. GWAS and functional studies suggest a role for altered DNA repair in the evolution of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. eLife 2023, 12, e75860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zein-Eddine, R.; Le Meur, A.; Skouloubris, S.; Jelsbak, L.; Refrégier, G.; Myllykallio, H. Genome wide analyses reveal the role of mutator phenotypes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug resistance emergence. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furió, V.; Moreno-Molina, M.; Chiner-Oms, Á.; Villamayor, L.M.; Torres-Puente, M.; Comas, I. An evolutionary functional genomics approach identifies novel candidate regions involved in isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, M.A.; Warner, D.F.; Mizrahi, V. Targeting DNA Replication and Repair for the Development of Novel Therapeutics against Tuberculosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M.; Adams, K.N.; Eldesouky, H.E.; Sherman, D.R. The evolving biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1027394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, J.L.; Menardo, F.; Trauner, A.; Borrell, S.; Gygli, S.M.; Loiseau, C.; Gagneux, S.; Hall, A.R. Transition bias influences the evolution of antibiotic resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruri, F.; Sterling, T.R.; Kaiga, A.W.; Blackman, A.; van der Heijden, Y.F.; Mayer, C.; Cambau, E.; Aubry, A. A systematic review of gyrase mutations associated with fluoroquinolone-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and a proposed gyrase numbering system. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Xia, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, T.; Zhou, L.; Xu, B.; Xu, S. Characterization of gyrA and gyrB mutations and fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from Hubei Province, China. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Braz. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.; Tahir, Z.; Mukhtar, N.; Sohail, M.; Saqalein, M.; Rehman, A. Fluoroquinolone resistance and mutational profile of gyrA in pulmonary MDR tuberculosis patients. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willby, M.; Chopra, P.; Lemmer, D.; Klein, K.; Dalton, T.L.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Cegielski, J.P.; Posey, J.E. Molecular Evaluation of Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Serial Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from Individuals Diagnosed with Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 65, e01663-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willby, M.; Sikes, R.D.; Malik, S.; Metchock, B.; Posey, J.E. Correlation between GyrA substitutions and ofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin cross-resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5427–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenagari, M.; Bakhtiari, M.; Mojtahedi, A.; Atrkar Roushan, Z. High frequency of mutations in gyrA gene associated with quinolones resistance in uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from the north of Iran. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2018, 21, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, N.J.; Charlier, C.; Dingley, A.J.; Baker, E.N.; Lott, J.S. Making sense of a missense mutation: Characterization of MutT2, a Nudix hydrolase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and the G58R mutant encoded in W-Beijing strains of M. tuberculosis. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morey-León, G.; Andrade-Molina, D.; Fernández-Cadena, J.C.; Berná, L. Comparative genomics of drug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Ecuador. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Agarwal, A.; Muniyappa, K. The intrinsic ATPase activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis UvrC is crucial for its damage-specific DNA incision function. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 1179–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Parulekar, R.S.; Barale, S.S.; Sonawane, K.D.; Muniyappa, K. Interrogating the substrate specificity landscape of UvrC reveals novel insights into its non-canonical function. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 3103–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Datta, D.; Khan, S.; Singh, Y.; Nandicoori, V.K.; Kumar, D. A clinical mutation in uvrA, A DNA repair gene, confers survival advantage to Mycobacterium tuberculosisin the host. Biorxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Martins, A.; Bongiorno, P.; Glickman, M.; Shuman, S. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the four DNA ligases of mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 20594–20606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvas, E.S.; Catoiu, E.; Mih, N.; Yurkovich, J.T.; Seif, Y.; Dillon, N.; Heckmann, D.; Anand, A.; Yang, L.; Nizet, V.; et al. Machine learning and structural analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pan-genome identifies genetic signatures of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrmann, M.S.; Perera, H.M.; Hoang, J.M.; Venkat, T.A.; Visser, B.J.; Bates, D.; Trakselis, M.A. Targeted chromosomal Escherichia coli:dnaB exterior surface residues regulate DNA helicase behavior to maintain genomic stability and organismal fitness. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Liang, L.; Shen, C.; Lin, D.; Li, J.; Lyu, L.; Liang, W.; Zhong, L.L.; Cook, G.M.; Doi, Y.; et al. A CRISPR-guided mutagenic DNA polymerase strategy for the detection of antibiotic-resistant mutations in M. tuberculosis. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 29, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Xiong, M.; Fu, L.Y.; Zhang, H.Y. Oxidative DNA damage is important to the evolution of antibiotic resistance: Evidence of mutation bias and its medicinal implications. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2013, 31, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, M.; Sakumi, K.; Fukumura, R.; Furuichi, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Hokama, M.; Ikemura, T.; Tsuzuki, T.; Gondo, Y.; Nakabeppu, Y. 8-oxoguanine causes spontaneous de novo germline mutations in mice. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, M.; Miura, T.; Furuichi, M.; Tominaga, Y.; Tsuchimoto, D.; Sakumi, K.; Nakabeppu, Y. A genome-wide distribution of 8-oxoguanine correlates with the preferred regions for recombination and single nucleotide polymorphism in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006, 16, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Jena, L. Understanding Rifampicin Resistance in Tuberculosis through a Computational Approach. Genom. Inform. 2014, 12, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, A.M.; Zaman, G.; Hussain, A.; Changhui, Y.; Rasul, A.; Hussain, A.; Bo, Z.; Bokhari, H.; Ibrahim, M. Comparative Genome Analysis of 2 Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Strains from Pakistan: Insights Globally Into Drug Resistance, Virulence, and Niche Adaptation. Evol. Bioinform. 2018, 14, 1176934318790252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koleske, B.N.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr.; Bishai, W.R. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome at 25 years: Lessons and lingering questions. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e173156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, L.D.; Tang, B.K.; Fan, X.Y.; Ma, H.; Zhao, G.P. Mycobacterial MazG safeguards genetic stability via housecleaning of 5-OH-dCTP. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakamata, M.; Takihara, H.; Iwamoto, T.; Tamaru, A.; Hashimoto, A.; Tanaka, T.; Kaboso, S.A.; Gebretsadik, G.; Ilinov, A.; Yokoyama, A.; et al. Higher genome mutation rates of Beijing lineage of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during human infection. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, C.B.; Lin, P.L.; Chase, M.R.; Shah, R.R.; Iartchouk, O.; Galagan, J.; Mohaideen, N.; Ioerger, T.R.; Sacchettini, J.C.; Lipsitch, M.; et al. Use of whole genome sequencing to estimate the mutation rate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during latent infection. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.V.; Rozhoňová, H.; Stoltzfus, A.; McCandlish, D.M.; Payne, J.L. Mutation bias shapes the spectrum of adaptive substitutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2119720119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeley, W.L.; Essigmann, J.M. Mechanisms of formation, genotoxicity, and mutation of guanine oxidation products. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebrián-Sastre, E.; Martín-Blecua, I.; Gullón, S.; Blázquez, J.; Castañeda-García, A. Control of Genome Stability by EndoMS/NucS-Mediated Non-Canonical Mismatch Repair. Cells 2021, 10, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fressatti Cardoso, R.; Martín-Blecua, I.; Pietrowski Baldin, V.; Meneguello, J.E.; Valverde, J.R.; Blázquez, J.; Castañeda-García, A. Noncanonical Mismatch Repair Protein NucS Modulates the Emergence of Antibiotic Resistance in Mycobacterium abscessus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0222822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Timochshuk, S.; Shamukhan, A.; Yakupov, B.; Auganova, D.; Zein, U.; Turgimbayeva, A.; Tarlykov, P.; Abeldenov, S. Genomic Surveillance of 3R Genes Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from Kazakhstan. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010026

Timochshuk S, Shamukhan A, Yakupov B, Auganova D, Zein U, Turgimbayeva A, Tarlykov P, Abeldenov S. Genomic Surveillance of 3R Genes Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from Kazakhstan. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleTimochshuk, Savva, Aldan Shamukhan, Bakhtiyar Yakupov, Dana Auganova, Ulan Zein, Aigerim Turgimbayeva, Pavel Tarlykov, and Sailau Abeldenov. 2026. "Genomic Surveillance of 3R Genes Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from Kazakhstan" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010026

APA StyleTimochshuk, S., Shamukhan, A., Yakupov, B., Auganova, D., Zein, U., Turgimbayeva, A., Tarlykov, P., & Abeldenov, S. (2026). Genomic Surveillance of 3R Genes Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates from Kazakhstan. Antibiotics, 15(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010026