Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton indotineae: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Features

3. Terbinafine Susceptibility

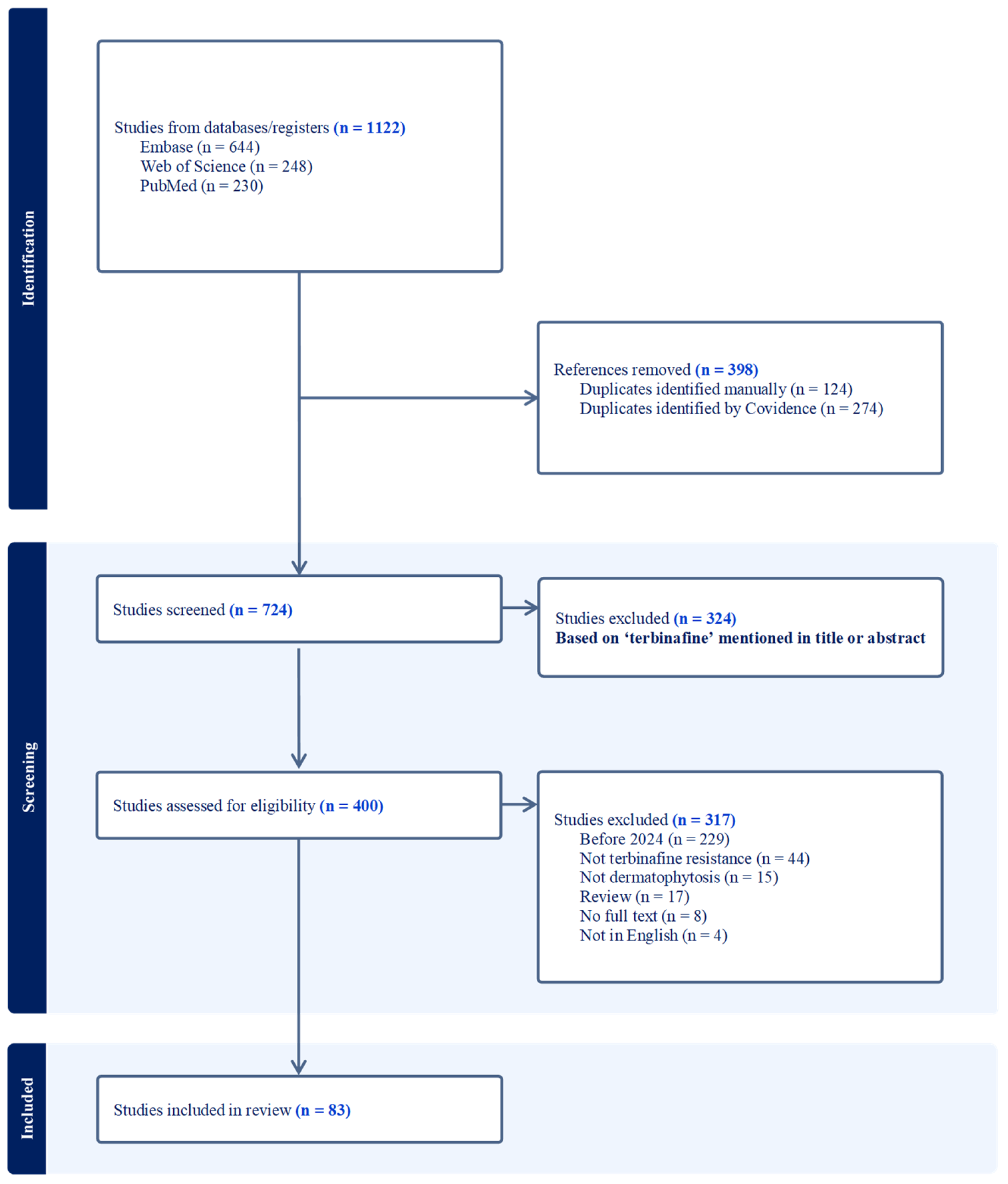

3.1. Literature Search

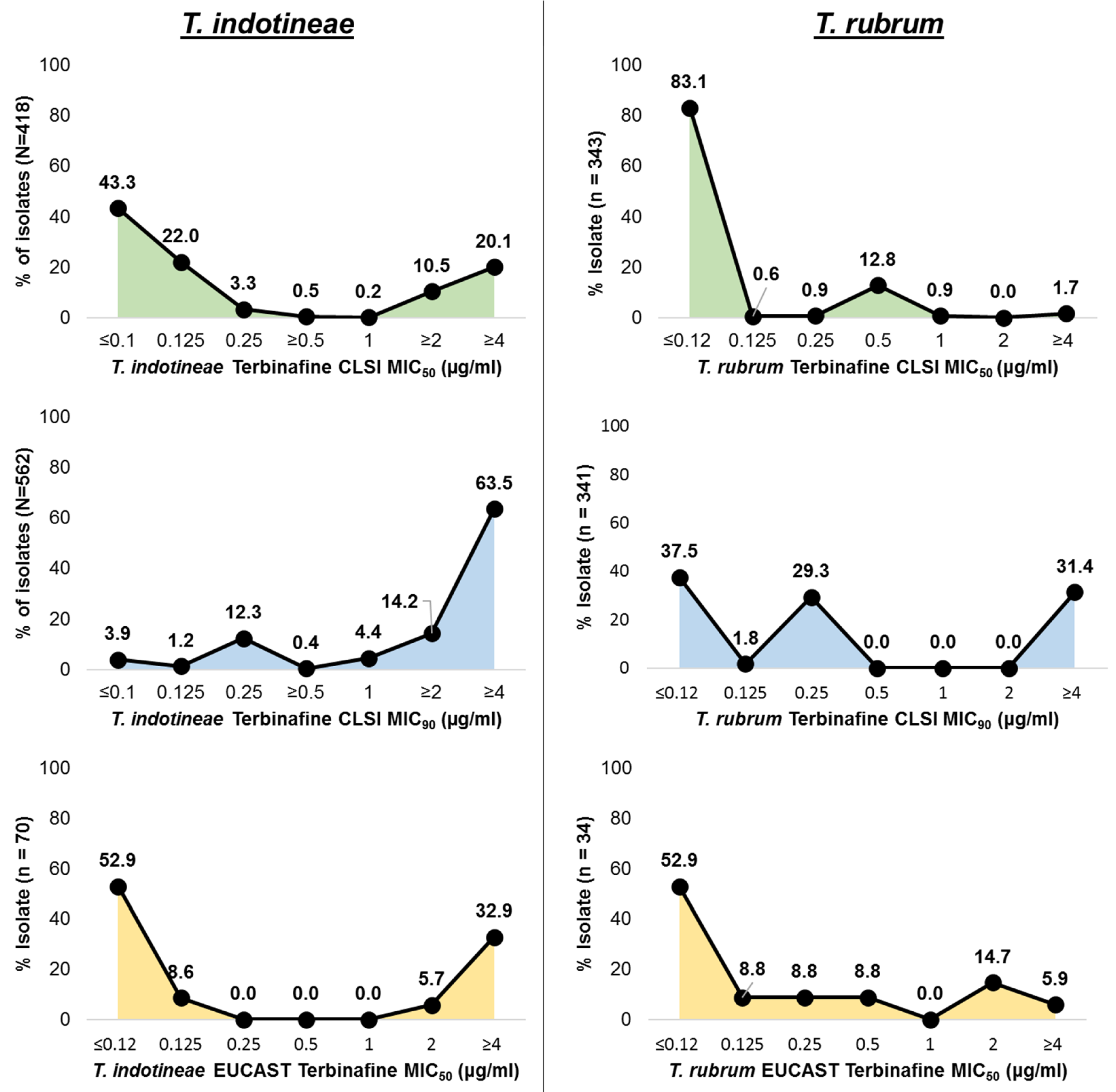

3.2. In Vitro Terbinafine Susceptibility

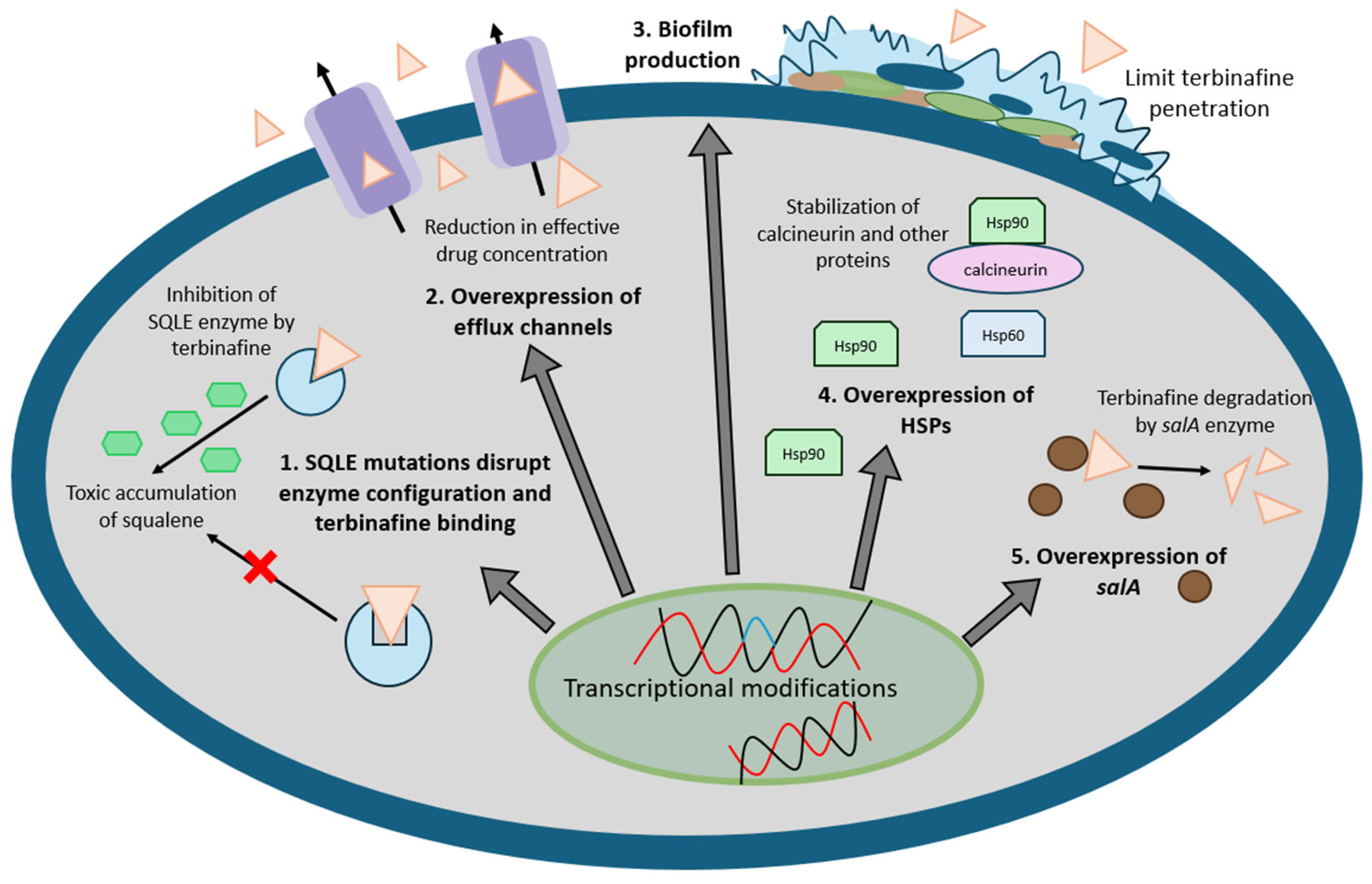

3.3. Mechanisms of Resistance

3.3.1. Single Nucleotide Variations (SNVs) in the Gene Encoding Squalene Epoxidase (SQLE)

3.3.2. Drug Efflux Channels

3.3.3. Biofilms

3.3.4. Heat Shock Proteins

3.3.5. Naphthalene Degradation

4. Treatments for Terbinafine Resistance

| Drug | Mechanism | Route | Pulse Therapy | Continuous Therapy | T. rubrum | T. indotineae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terbinafine | Inhibits squalene epoxidase | Oral, topical | 250 mg BID, 1 week/month (not commonly used) | 250–500 mg/day, 4–12 weeks | Highly effective [124] | High resistance [124] |

| Griseofulvin | Inhibits microtubule function | Oral | Rarely used in pulse | 10–20 mg/kg/day, 6–12 weeks | Somewhat effective but therapy for long duration [21] | Limited data, uncertain efficacy [21] |

| Itraconazole | Inhibits lanosterol 14α-demethylase | Oral | 200 mg BID, 1 week/month, 1–3 pulses (superficial fungal infections); 3–4 or more pulses (onychomycosis) | 100–200–400 mg/day, 4–12 weeks | Effective [126] | Preferred alternative to terbinafine [126] |

| Voriconazole | Inhibits lanosterol 14α-demethylase | Oral, topical | Not typically used | 200–400 mg/day | Effective but rarely needed [111] | Effective in resistant cases. Topical voriconazole effective in selected cases [111] |

| Posaconazole | Inhibits lanosterol 14α-demethylase | Oral | Not commonly used | 300 mg/day | Effective but rarely needed [127] | Used in recalcitrant cases [70] |

| Fluconazole | Inhibits lanosterol 14α-demethylase | Oral | 150–300 mg once weekly | 100–200 mg/day | Less effective than terbinafine/itraconazole [21] | Low efficacy, resistance reported [21] |

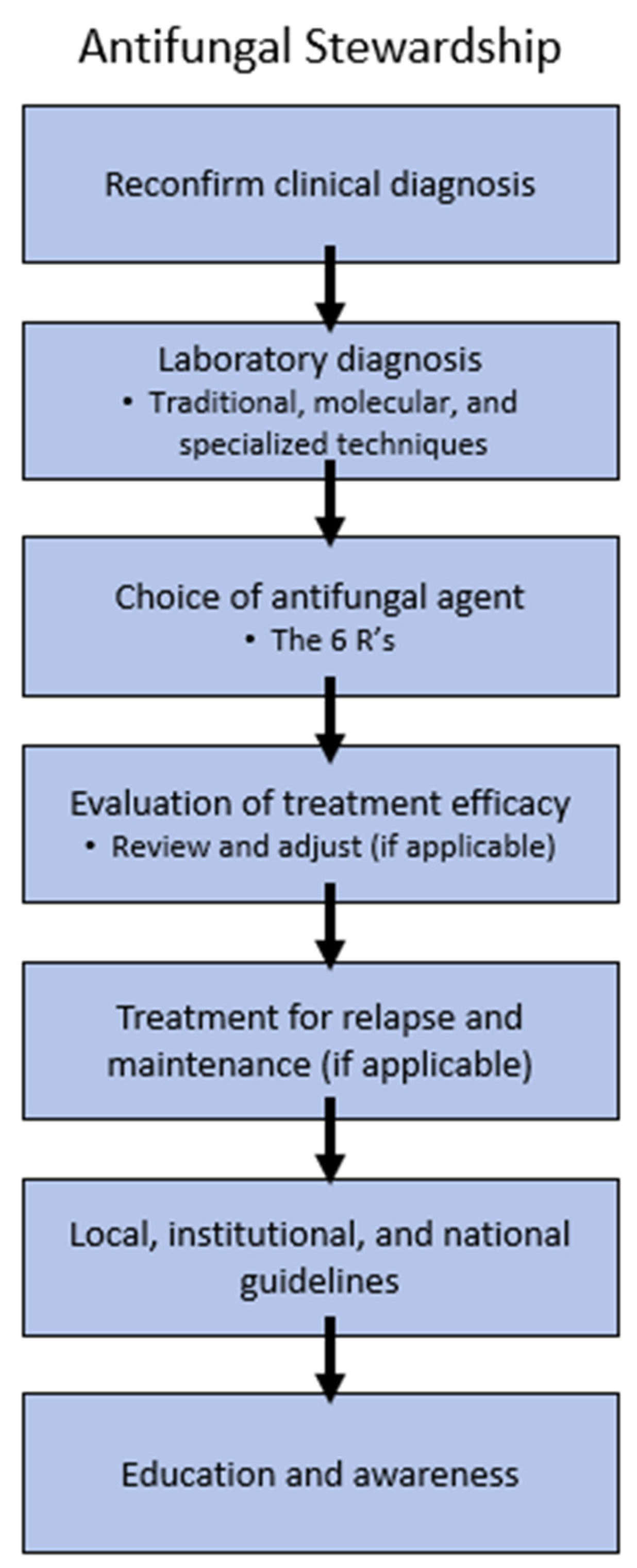

5. Antifungal Stewardship

5.1. Reconfirm Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis

5.2. Choice of Antifungal Agent

5.3. AFST

5.4. Institutional, Local, and National Guidelines

5.5. Education and Awareness

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moskaluk, A.E.; VandeWoude, S. Current Topics in Dermatophyte Classification and Clinical Diagnosis. Pathogens 2022, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Mann, A.; Polla Ravi, S.; Wang, T. Navigating Fungal Infections and Antifungal Stewardship: Drug Resistance, Susceptibility Testing, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Future Directions. Ital. J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 159, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, K.; Gold, J.A.W.; Wu, K.; Lipner, S.R. High Frequency of Self-Diagnosis and Self-Treatment in a Nationally Representative Survey about Superficial Fungal Infections in Adults-United States, 2022. J. Fungi 2022, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathadka, S.; Yan, V.K.C.; Neoh, C.F.; Al-Badriyeh, D.; Kong, D.C.M.; Slavin, M.A.; Cowling, B.J.; Hung, I.F.N.; Wong, I.C.K.; Chan, E.W. Global Consumption Trend of Antifungal Agents in Humans from 2008 to 2018: Data from 65 Middle- and High-Income Countries. Drugs 2022, 82, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkes, M.J.M.; Scott, L.J.; Goa, K.L. Terbinafine: A Review of Its Use in Onychomycosis in Adults. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003, 4, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Polla Ravi, S.; Talukder, M.; Mann, A. Effectiveness and Safety of Oral Terbinafine for Dermatophyte Distal Subungual Onychomycosis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Leidich, S.D.; Isham, N.; Leitner, I.; Ryder, N.S.; Ghannoum, M.A. Clinical Trichophyton rubrum Strain Exhibiting Primary Resistance to Terbinafine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, B.; Ghannoum, M.A.; Ryder, N.S. Biochemical Characterization of Terbinafine-Resistant Trichophyton rubrum Isolates. Med. Mycol. 2004, 42, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.B.; Lisboa, C. A Systematic Review on the Emergence of Terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton indotineae in Europe: Time to Act? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Wang, T.; Mann, A.; Polla Ravi, S.; Talukder, M.; Lincoln, S.A.; Foreman, H.-C.; Kaplan, B.; Galili, E.; Piguet, V.; et al. Antifungal Resistance in Dermatophytes—Review of the Epidemiology, Diagnostic Challenges and Treatment Strategies for Managing Trichophyton indotineae Infections. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2024, 22, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Elewski, B.; Joseph, W.S.; Lipner, S.R.; Daniel, C.R.; Tosti, A.; Guenin, E.; Ghannoum, M. Treatment of Onychomycosis in an Era of Antifungal Resistance: Role for Antifungal Stewardship and Topical Antifungal Agents. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; Hatch, M.; Ghannoum, M.; Elewski, B.E. Treatment-Resistant Dermatophytosis: A Representative Case Highlighting an Emerging Public Health Threat. JAAD Case Rep. 2020, 6, 1153–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.M.E.; Blaya Alvarez, B.; Polcz, M. Multi-drug Resistant Dermatophyte Infections in Western Sydney: A Retrospective Case Series. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2022, 63, e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nofal, A.; Fawzy, M.M.; El-Hawary, E.E. Successful Treatment of Resistant Onychomycosis with Voriconazole in a Liver Transplant Patient. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunte, D.M.L.; Pereiro-Ferreirós, M.; Rodríguez-Cerdeira, C.; Sergeev, A.Y.; Arabatzis, M.; Prohić, A.; Piraccini, B.M.; Lecerf, P.; Nenoff, P.; Kotrekhova, L.P.; et al. Emerging Antifungal Treatment Failure of Dermatophytosis in Europe: Take Care or It May Become Endemic. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, J.; Noguchi, H.; Shimizu, T.; Hiruma, M.; Harada, K.; Kano, R. Epidemiological Study of Antifungal-Resistant Dermatophytes Isolated from Japanese Patients. J. Dermatol. 2023, 50, 1068–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Masih, A.; Monroy-Nieto, J.; Singh, P.K.; Bowers, J.; Travis, J.; Khurana, A.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Meis, J.F.; Chowdhary, A. A Unique Multidrug-Resistant Clonal Trichophyton Population Distinct from Trichophyton mentagrophytes/Trichophyton interdigitale Complex Causing an Ongoing Alarming Dermatophytosis Outbreak in India: Genomic Insights and Resistance Profile. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 133, 103266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobrega de Almeida, J., Jr.; dos Santos, A.R.; Roberto de Trindade, M.S.; Gold, J.A.; Razo, F.P.; Gonçalves, S.S.; Dorlass, E.G.; de Mello Ruiz, R.; Pasternak, J.; Mangueira, C.L.; et al. Trichophyton indotineae Infection, São Paulo, Brazil, 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 1049–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Kim, S.L.; Jang, Y.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, D.W.; Bang, Y.J.; Jun, J.B. Increasing Prevalence of Trichophyton rubrum Identified through an Analysis of 115,846 Cases over the Last 37 Years. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Peng, J.; Jin, Q. Transcriptional Profiles of Response to Terbinafine in Trichophyton rubrum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 82, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonego, B.; Corio, A.; Mazzoletti, V.; Zerbato, V.; Benini, A.; di Meo, N.; Zalaudek, I.; Stinco, G.; Errichetti, E.; Zelin, E. Trichophyton indotineae, an Emerging Drug-Resistant Dermatophyte: A Review of the Treatment Options. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elewski, B.E. Onychomycosis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.Q.; Liu, X.Q.; Xu, H.B.; Zeng, X.S.; Chen, W.; Li, X.F. Deep Dermatophytosis Caused by Trichophyton rubrum: Report of Two Cases. Mycoses 2007, 50, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Talukder, M.; Carviel, J.L.; Cooper, E.A.; Piguet, V. Combatting Antifungal Resistance: Paradigm Shift in the Diagnosis and Management of Onychomycosis and Dermatomycosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 1706–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolrasouli, A.; Borman, A.M.; Johnson, E.M.; Hay, R.J.; Arias, M. Terbinafine-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae Causing Extensive Dermatophytosis in a Returning Traveller, London, UK. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 49, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolrasouli, A.; Barton, R.C.; Borman, A.M. Spread of Antifungal-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae, United Kingdom, 2017–2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.; Shenoy, M.M.; Pai, V. Antifungal Susceptibility of Dermatophyte Isolates from Patients with Chronic and Recurrent Dermatophytosis. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2024, 16, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berstecher, N.; Burmester, A.; Gregersen, D.M.; Tittelbach, J.; Wiegand, C. Trichophyton indotineae Erg1Ala448Thr Strain Expressed Constitutively High Levels of Sterol 14-α Demethylase Erg11B MRNA, While Transporter MDR3 and Erg11A MRNA Expression Was Induced After Addition of Short Chain Azoles. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.S.I.; Verma, S.B.; Illigner, G.M.; Uhrlaß, S.; Klonowski, E.; Burmester, A.; Noor, T.; Nenoff, P. Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS Genotype VIII/Trichophyton indotineae Infection and Antifungal Resistance in Bangladesh. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.S.; Todd, G.C.; Zhu, Y.; Sikora, M.; Akoh, C.C.; Jakus, J.; Lipner, S.R.; Graber, K.B.; Acker, K.P.; Morales, A.E.; et al. Clinical Course, Antifungal Susceptibility, and Genomic Sequencing of Trichophyton indotineae. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paepe, R.; Normand, A.C.; Uhrlaß, S.; Nenoff, P.; Piarroux, R.; Packeu, A. Resistance Profile, Terbinafine Resistance Screening and MALDI-TOF MS Identification of the Emerging Pathogen Trichophyton indotineae. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duus, L. Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton Species From Patients with Recalcitrant Infections Detected by the EUCAST Broth Microdilution Method and DermaGenius Resistance Multiplex PCR Kit. Mycoses 2025, 68, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukada, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Nakazono, M.; Ohyachi, K.; Takeda, A.; Yaguchi, T.; Okada, M.; Sato, T. A Case of Tinea Faciei Due to Trichophyton indotineae with Steroid Rosacea Related to Topical Over-The-Counter Drugs Purchased Outside of Japan. Med. Mycol. J. 2024, 65, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghani, I.; Babaie, M.; Hoseinnejad, A.; Rezaei-Matehkolaei, A.; Mofarrah, R.; Yahyazadeh, Z.; Kermani, F.; Javidnia, J.; Shokohi, T.; Azish, M.; et al. High Prevalence of Terbinafine Resistance Among Trichophyton mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale Species Complex, a Cross-Sectional Study from 2021 to 2022 in Northern Parts of Iran. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghani, I.; Hashemi, S.M.; Abastabar, M.; Yahyazadeh, Z.; Ebrahimi-Barough, R.; Hoseinnejad, A.; Teymoori, A.; Azadeh, H.; Rashidi, M.; Aghili, S.R.; et al. In Vitro and Silico Activity of Piperlongumine against Azole-Susceptible/Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and Terbinafine-Susceptible/Resistant Trichophyton Species. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 111, 116578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, S.; Noguchi, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Nojo, H.; Kano, R. Terbinafine-resistant Tinea Pedis and Tinea Unguium in Japanese Military Personnel. J. Dermatol. 2024, 51, 1256–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, J.; Nojyo, H.; Harada, K.; Kano, R. Development of Treatment Strategies by Comparing the Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations and Minimum Fungicidal Concentrations of Azole Drugs in Dermatophytes. J. Dermatol. 2024, 51, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Liang, C.T.; Zhong, J.J.; Kong, X.; Xu, H.X.; Xu, C.C.; Fu, M.H. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Based Photodynamic Therapy in Combination with Antifungal Agents for Adult Kerion and Facial Ulcer Caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 45, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarczyková, D.; Lysková, P.; Švarcová, M.; Kuklová, I.; Dobiáš, R.; Mallátová, N.; Kolařík, M.; Hubka, V. Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Trichophyton rubrum in the Czech Republic: A Prospective Multicentric Study. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemes, T.H.; Nascentes, J.A.S.; Regasini, L.O.; Siqueira, J.P.Z.; Maschio-Lima, T.; Pattini, V.C.; Ribeiro, M.D.; de Almeida, B.G.; de Almeida, M.T.G. Combinatorial Effect of Fluconazole, Itraconazole, and Terbinafine with Different Culture Extracts of Candida parapsilosis and Trichophyton spp. against Trichophyton rubrum. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 27, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madarasingha, N.P.; Thabrew, H.; Uhrlass, S.; Eriyagama, S.; Reinal, D.; Jayasekera, P.I.; Nenoff, P. Dermatophytosis Caused by Trichophyton indotineae (Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS Genotype VIII) in Sri Lanka. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 111, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, H.R.; Shams-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Salehi, Z.; Razzaghi-Abyaneh, M. Epidemiological Trends, Antifungal Drug Susceptibility and SQLE Point Mutations in Etiologic Species of Human Dermatophytosis in Al-Diwaneyah, Iraq. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maschio-Lima, T.; Lemes, T.H.; Marques, M.D.R.; Siqueira, J.P.Z.; de Almeida, B.G.; Caruso, G.R.; Von Zeska Kress, M.R.; de Tarso da Costa, P.; Regasini, L.O.; de Almeida, M.T.G. Synergistic Activity between Conventional Antifungals and Chalcone-Derived Compound against Dermatophyte Fungi and Candida spp. Int. Microbiol. 2025, 28, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTaggart, L.R.; Cronin, K.; Ruscica, S.; Patel, S.N.; Kus, J.V. Emergence of Terbinafine-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae in Ontario, Canada, 2014–2023. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e0153524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechidi, P.; Holien, J.; Grando, D.; Huynh, T.; Lawrie, A.C. New Sources of Resistance to Terbinafine Revealed and Squalene Epoxidase Modelled in the Dermatophyte Fungus Trichophyton interdigitale from Australia. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi Mirsaid, R.; Falahati, M.; Farahyar, S.; Ghasemi, Z.; Roudbary, M.; Mahmoudi, S. In Vitro Antifungal Activity of Eucalyptol and Its Interaction with Antifungal Drugs Against Clinical Dermatophyte Isolates Including Trichophyton indotineae. Discover. Public Health 2024, 21, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; Anzawa, K.; Bernales-Mendoza, A.M.; Shimizu, A. Case of Tinea Corporis Caused by a Terbinafine-Sensitive Trichophyton indotineae Strain in a Vietnamese Worker in Japan. J. Dermatol. 2025, 52, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, A.; Elshaer, M.; Long, L.; McCormick, T.S.; Elewski, B.; Ghannoum, M.A. Antifungal Activity of Efinaconazole Compared with Fluconazole, Itraconazole, and Terbinafine Against Terbinafine- and Itraconazole-Resistant/Susceptible Clinical Isolates of Dermatophytes, Candida, and Molds. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2024, 114, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Ngullie, C.; Khattri, A.; Gupta, H.; Singh, K.; Paul, R. Dermatophyte Prevalence and Antifungal Resistance in Central India: Insights from a Clinical and Mycological Study. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. Res. 2024, 15, 858–861. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, L.Z.; Shams-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Salehi, Z.; Razzaghi-Abyaneh, M. Increased Terbinafine Resistance among Clinical Genotypes of Trichophyton mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale Species Complex Harboring Squalene Epoxidase Gene Mutations. J. Mycol. Med. 2024, 34, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Sabater, A.; Cordier, C.; Normand, A.C.; Bidaud, A.L.; Cremer, G.; Bouchara, J.P.; Huguenin, A.; Imbert, S.; Challende, I.; Brin, C.; et al. Autochthonous Trichophyton rubrum Terbinafine Resistance in France: Assessment of Antifungal Susceptibility Tests. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1613–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, T.M.C.; Santona, A.; Ton Nu, P.A.; Cao, L.C.; Tran Thi, G.; Do, T.B.T.; Ha, T.N.T.; Vo Minh, T.; Nguyen, P.V.; Ton That, D.D.; et al. Detection of Terbinafine-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae Isolates within the Trichophyton mentagrophytes Species Complex Isolated from Patients in Hue City, Vietnam: A Comprehensive Analysis. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, M.; Akhtari, J.; Jaafari, M.R.; Yahyazadeh, Z.; Shokohi, T.; Haghani, I.; Farmani, P.; Barough, R.E.; Badali, H.; Abastabar, M. In Vitro Activity of Nanoliposomal Amphotericin B against Terbinafine-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae Isolates. Int. Microbiol. 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oğuz, I.D.; Direkel; Akşan, B.; Kulakli, S.; Aksoy, S. In Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility of the Dermatophytes: A Single Center Study from Eastern Black Sea Region of Turkey. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 28, 2144–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladzad, V.; Nasrollahi Omran, A.; Haghani, I.; Nabili, M.; Seyedmousavi, S.; Hedayati, M.T. Multi-Drug Resistance Trichophyton indotineae in a Stray Dog. Res. Vet. Sci. 2024, 166, 105105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.F.; Valeriano, C.A.T.; Buonafina-Paz, M.D.S.; Souza-Motta, C.M.; Machado, A.R.; Neves, R.P.; Bezerra, J.D.P.; Arantes, T.D.; de Hoog, S.; Magalhães, O.M.C. Molecular Verification of Trichophyton in the Brazilian URM Culture Collection. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattini, V.C.; Polaquini, C.R.; Lemes, T.H.; Brizzotti-Mazuchi, N.S.; de Cássia Orlandi Sardi, J.; Paziani, M.H.; von Zeska Kress, M.R.; de Almeida, M.T.G.; Regasini, L.O. Antifungal Activity of 3,3′-Dimethoxycurcumin (DMC) against Dermatophytes and Candida Species. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 77, ovae019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacheli, R.; Egrek, S.; El Moussaoui, K.; Darfouf, R.; Adjetey, A.B.; Hayette, M.P. Evaluation of Currently Available Laboratory Methods to Detect Terbinafine Resistant Dermatophytes Including a Gradient Strip for Terbinafine, EUCAST Microdilution E.Def 11.0, a Commercial Real-Time PCR Assay, Squalene Epoxidase Sequencing and Whole Genome Sequencing. Mycoses 2024, 67, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Balhara, M.; Dutta, D.; Chaudhuri, S.; Ghosh, S.; Sardana, K. Synergistic Effect of Punica granatum Derived Antifungals on Strains with Clinical Failure to Terbinafine and Azoles Drugs. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2024, 24, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, M.; Walker, B.; Nabhani, S.; Odon, A.; Riel, S.; Jäckel, A. Activity of Amorolfine or Ciclopirox in Combination with Terbinafine Against Pathogenic Fungi in Onychomycosis—Results of an In Vitro Investigation. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, H.; Henriques, C.; Simões, H.; Veríssimo, C.; Sabino, R. Prevalence of T. rubrum and T. interdigitale Exhibiting High MICs to Terbinafine in Clinical Samples Analyzed in the Portuguese Mycology Reference Laboratory. Pathogens 2025, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Shao, J.; de Hoog, S.; Verweij, P.; Bai, L.; Richardson, R.; Richardson, M.; Wan, Z.; Li, R.; Yu, J.; et al. Emerging Antifungal Resistance in Trichophyton mentagrophytes: Insights from Susceptibility Profiling and Genetic Mutation Analysis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2450026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, D.; Dogra, S.; Singh, S.; Shah, S.; Narang, T.; Kaur, H.; Walia, K.; Ghosh, A.; Handa, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; et al. Prolonged Treatment of Dermatophytosis Caused by Trichophyton indotinea with Terbinafine or Itraconazole Impacts Better Outcomes Irrespective of Mutation in the Squalene Epoxidase Gene. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Prasad, A.; Singh, G.; Hazarika, N.; Gupta, P.; Kaistha, N. Comparative Analysis of Antifungal Susceptibility in Trichophyton Species Using Broth Microdilution Assay: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e77113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivack, S.; Gold, J.A.W.; Lockhart, S.R.; Anand, P.; Quilter, L.A.S.; Smith, D.J.; Bowen, B.; Gould, J.M.; Eltokhy, A.; Gamal, A.; et al. Potential Sexual Transmission of Antifungal-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 807–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrlaß, S.; Mey, S.; Koch, D.; Mütze, H.; Krüger, C.; Monod, M.; Nenoff, P. Dermatophytes and Skin Dermatophytoses in Southeast Asia—First Epidemiological Survey from Cambodia. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, S.; Rajput, M.S. Species Identification and Differentiation of Dermatophytes, Antifungal Susceptibility Profile from a Tertiary Care Centre in Central India. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 31, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.P.; Kumar, M.; Seema, K.; Kumar, A.; Boipai, M.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, A.K. Antifungal Patterns of Dermatophytes: A Pathway to Antifungal Stewardship in Eastern India. Cureus 2024, 16, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Song, Z.; Su, X.; Li, T.; Xu, J.; He, X.; Yang, Y.; Chang, B.; Kang, Y. Molecular Epidemiology and Antifungal Susceptibility of Dermatophytes and Candida Isolates in Superficial Fungal Infections at a Grade A Tertiary Hospital in Northern China. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete-Gibas, C.F.; Mele, J.; Patterson, H.P.; Sanders, C.J.; Ferrer, D.; Garcia, V.; Fan, H.; David, M.; Wiederhold, N.P. Terbinafine-Resistant Dermatophytes and the Presence of Trichophyton indotineae in North America. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0056223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannoum, M.A.; Rice, L.B. Antifungal Agents: Mode of Action, Mechanisms of Resistance, and Correlation of These Mechanisms with Bacterial Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Masih, A.; Khurana, A.; Singh, P.K.; Gupta, M.; Hagen, F.; Meis, J.F.; Chowdhary, A. High Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton Interdigitale Isolates in Delhi, India Harbouring Mutations in the Squalene Epoxidase Gene. Mycoses 2018, 61, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruithoff, C.; Gamal, A.; McCormick, T.S.; Ghannoum, M.A. Dermatophyte Infections Worldwide: Increase in Incidence and Associated Antifungal Resistance. Life 2023, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; Maeda, M.; Alshahni, M.M.; Tanaka, R.; Yaguchi, T.; Bontems, O.; Salamin, K.; Fratti, M.; Monod, M. Terbinafine Resistance of Trichophyton Clinical Isolates Caused by Specific Point Mutations in the Squalene Epoxidase Gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00115-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Peres, N.T.A.; Lang, E.A.S.; Gomes, E.V.; Quaresemin, N.R.; Martins, M.P.; Lopes, L.; Rossi, A. Dermatophyte Resistance to Antifungal Drugs: Mechanisms and Prospectus. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 374718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Spruijtenburg, B.; Abhishek; Shaw, D.; de Groot, T.; Meijer, E.F.J.; Narang, T.; Dogra, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; Meis, J.F.; et al. Whole Genome Sequence Analysis of Terbinafine Resistant and Susceptible Trichophyton Isolates from Human and Animal Origin. Mycopathologia 2025, 190, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, P.; Fattahi, M.; Ghaderi, A.; Firooz, A.; Shirvani, F.; Alkhen, A.; Zamani, S. Terbinafine-resistant T. Indotineae Due to F397L/L393S or F397L/L393F Mutation among Corticoid-related Tinea Incognita Patients. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2024, 22, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasey, J.V.; Gonçalves, R.D.J.; Valinoto, G.C.J.; Carvalho, G.d.S.M.; Celestrino, G.A.; Reis, A.P.C.; Lima, A.P.C.; Costa, A.C.d.; Melhem, M.d.S.C.; Benard, G.; et al. First Case of Trichophyton indotineae in Brazil: Clinical and Mycological Criteria and Genetic Identification of Terbinafine Resistance. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, S.; Abou-Chakra, N.; Oldberg, K.; Chryssanthou, E.; Young, E. Terbinafine Resistant Trichophyton indotineae in Sweden. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2025, 105, adv42089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, E.; Lubitz, I.; Shemer, A.; Astman, N.; Pevzner, K.; Gazit, Z.; Segal, O.; Lyakhovitsky, A.; Halevi, S.; Baum, S.; et al. First Reported Cases of Terbinafine-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae Isolates in Israel: Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics and Response to Treatment. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Sabater, A.; Normand, A.C.; Bidaud, A.L.; Cremer, G.; Foulet, F.; Brun, S.; Bonnal, C.; Aït-Ammar, N.; Jabet, A.; Ayachi, A.; et al. Terbinafine Resistance in Dermatophytes: A French Multicenter Prospective Study. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunte, D.M.L.; Hare, R.K.; Jørgensen, K.M.; Jørgensen, R.; Deleuran, M.; Zachariae, C.O.; Thomsen, S.F.; Bjørnskov-Halkier, L.; Kofoed, K.; Arendrup, M.C. Emerging Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton: Clinical Characteristics, Squalene Epoxidase Gene Mutations, and a Reliable EUCAST Method for Detection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01126-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Tang, C.; Singh, A.; Ahmed, S.A.; Al-Hatmi, A.M.S.; Chowdhary, A.; Nenoff, P.; Gräser, Y.; Hainsworth, S.; Zhan, P.; et al. Antifungal Susceptibility and Mutations in the Squalene Epoxidase Gene in Dermatophytes of the Trichophyton mentagrophytes Species Complex. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0005621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabet, A.; Brun, S.; Normand, A.C.; Imbert, S.; Akhoundi, M.; Dannaoui, E.; Audiffred, L.; Chasset, F.; Izri, A.; Laroche, L.; et al. Extensive Dermatophytosis Caused by Terbinafine-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.; Monod, M.; Salamin, K.; Burmester, A.; Uhrlaß, S.; Wiegand, C.; Hipler, U.C.; Krüger, C.; Koch, D.; Wittig, F.; et al. Alarming India-Wide Phenomenon of Antifungal Resistance in Dermatophytes: A Multicentre Study. Mycoses 2020, 63, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellière, S.; Joannard, B.; Benderdouche, M.; Mingui, A.; Gits-Muselli, M.; Hamane, S.; Alanio, A.; Petit, A.; Gabison, G.; Bagot, M.; et al. Emergence of Difficult-to-Treat Tinea Corporis Caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes Complex Isolates, Paris, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, S.; Shamsizadeh, F.; Pchelin, I.M.; Rezaei-Matehhkolaei, A.; Mahmoudabadi, A.Z.; Valadan, R.; Ansari, S.; Katiraee, F.; Pakshir, K.; Zomorodian, K.; et al. Emergence of Terbinafine Resistant Trichophyton mentagrophytes in Iran, Harboring Mutations in the Squalene Epoxidase (SQLE) Gene. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.P.; Franceschini, A.C.C.; Jacob, T.R.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Compensatory Expression of Multidrug-Resistance Genes Encoding ABC Transporters in Dermatophytes. J. Med. Microbiol. 2016, 65, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Mann, A.; Polla Ravi, S.; Wang, T. An Update on Antifungal Resistance in Dermatophytosis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, R.; Hsiao, Y.H.; Han, H.S.; Chen, C.; Hasegawa, A.; Kamata, H. Resistance Mechanism in a Terbinafine-Resistant Strain of Microsporum Canis. Mycopathologia 2018, 183, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, L.E.; Steinbach, W.J. Stress, Drugs, and Evolution: The Role of Cellular Signaling in Fungal Drug Resistance. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MMartinez-Rossi, N.M.; Jacob, T.R.; Sanches, P.R.; Peres, N.T.; Lang, E.A.; Martins, M.P.; Rossi, A. Heat Shock Proteins in Dermatophytes: Current Advances and Perspectives. Curr. Genom. 2016, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fachin, A.L.; Ferreira-Nozawa, M.S.; Maccheroni, W.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Role of the ABC Transporter TruMDR2 in Terbinafine, 4-Nitroquinoline N-Oxide and Ethidium Bromide Susceptibility in Trichophyton rubrum. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 55, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.B.; Panda, S.; Nenoff, P.; Singal, A.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Uhrlass, S.; Das, A.; Bisherwal, K.; Shaw, D.; Vasani, R.; et al. The Unprecedented Epidemic-like Scenario of Dermatophytosis in India: III. Antifungal Resistance and Treatment Options. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2021, 87, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.D.O. A Review of Recent Research on Antifungal Agents against Dermatophyte Biofilms. Med. Mycol. 2021, 59, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.M.; Costa-Orlandi, C.B.; Bila, N.M.; Vaso, C.O.; Gonçalves, L.N.C.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S. A Two-Way Road: Antagonistic Interaction Between Dual-Species Biofilms Formed by Candida albicans/Candida parapsilosis and Trichophyton rubrum. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 534005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukabri, N.; Corpologno, S.; Bougnoux, M.-E.; Dalenda, I.; Euch, E.; Sadfi-Zouaoui, N.; Simonetti, G. In Vitro Biofilms and Antifungal Susceptibility of Dermatophyte and Non-Dermatophyte Moulds Involved in Foot Mycosis. Mycoses 2017, 61, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, S.; Sasanipoor, F.; Khodadadi, H.; Rezaei-Matehkolaei, A.; Jowkar, F.; Zomorodian, K.; Kharazi, M.; Mohammadi, T.; Nouripour-Sisakht, S.; Nasr, R.; et al. Quantitative Analysis of In Vitro Biofilm Formation by Clinical Isolates of Dermatophyte and Antibiofilm Activity of Common Antifungal Drugs. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 62, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilhante, R.S.N.; Correia, E.E.M.; Guedes, G.M.d.M.; de Oliveira, J.S.; Castelo-Branco, D.d.S.C.M.; Cordeiro, R.d.A.; Pinheiro, A.d.Q.; Chaves, L.J.Q.; Pereira Neto, W.d.A.; Sidrim, J.J.C.; et al. In Vitro Activity of Azole Derivatives and Griseofulvin against Planktonic and Biofilm Growth of Clinical Isolates of Dermatophytes. Mycoses 2018, 61, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Branco, D.d.S.C.M.; Aguiar, L.d.; Araújo, G.d.S.; Lopes, R.G.P.; Sales, J.d.A.; Pereira-Neto, W.A.; Pinheiro, A.d.Q.; Paixão, G.C.; Cordeiro, R.d.A.; Sidrim, J.J.C.; et al. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Biofilms of Dermatophytes: A New Panorama for the Study of Antifungal Drugs. Biofouling 2020, 36, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, T.R.; Peres, N.T.A.; Martins, M.P.; Lang, E.A.S.; Sanches, P.R.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Heat Shock Protein 90 (Hsp90) as a Molecular Target for the Development of Novel Drugs against the Dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 166626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafayette, S.L.; Collins, C.; Zaas, A.K.; Schell, W.A.; Betancourt-Quiroz, M.; Leslie Gunatilaka, A.A.; Perfect, J.R.; Cowen, L.E. PKC Signaling Regulates Drug Resistance of the Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans via Circuitry Comprised of Mkc1, Calcineurin, and Hsp90. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowen, L.E. The Evolution of Fungal Drug Resistance: Modulating the Trajectory from Genotype to Phenotype. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvvadi, P.R.; Lee, S.C.; Heitman, J.; Steinbach, W.J. Calcineurin in Fungal Virulence and Drug Resistance: Prospects for Harnessing Targeted Inhibition of Calcineurin for an Antifungal Therapeutic Approach. Virulence 2017, 8, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, L.E.; Lindquist, S. Cell Biology: Hsp90 Potentiates the Rapid Evolution of New Traits: Drug Resistance in Diverse Fungi. Science 2005, 309, 2185–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stie, J.; Fox, D. Calcineurin Regulation in Fungi and Beyond. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graminha, M.A.S.; Rocha, E.M.F.; Prade, R.A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Terbinafine Resistance Mediated by Salicylate 1-Monooxygenase in Aspergillus Nidulans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3530–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Peres, N.T.A.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Martins, M.P.; Rossi, A. State-of-the-Art Dermatophyte Infections: Epidemiology Aspects, Pathophysiology, and Resistance Mechanisms. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, N.T.; Sanches, P.R.; Falco, J.P.; Silveira, H.C.; Paião, F.G.; Maranhão, F.C.; Gras, D.E.; Segato, F.; Cazzaniga, R.A.; Mazucato, M.; et al. Transcriptional Profiling Reveals the Expression of Novel Genes in Response to Various Stimuli in the Human Dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.L.; Lang, E.A.S.; Segato, F.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Terbinafine Resistance Conferred by Multiple Copies of the Salicylate 1-Monooxygenase Gene in Trichophyton rubrum. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Sharath, S.; Sardana, K.; Chowdhary, A.; Panesar, S. Therapeutic Updates on the Management of Tinea Corporis or Cruris in the Era of Trichophyton indotineae: Separating Evidence from Hype—A Narrative Review. Indian J. Dermatol. 2023, 68, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotti, S.; Cruciani, D.; Spina, S.; Piscioneri, V.; Natalini, Y.; Pezzotti, G.; Sabbatucci, M.; Papini, M. A Terbinafine Sensitive Trichophyton indotineae Strain in Italy: The First Clinical Case of Tinea Corporis and Onychomycosis. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasch, J.; Gräser, Y.; Beck-Jendroscheck, V.; Voss, K.; Torz, K.; Walther, G.; Schwarz, T. “Indian” Strains of Trichophyton mentagrophytes with Reduced Itraconazole Susceptibility in Germany. JDDG J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. 2021, 19, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, M.; Kraemer, K.T. Dermatopharmacology of Ciclopirox Nail Lacquer Topical Solution 8% in the Treatment of Onychomycosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 43, S57–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.Y.; Wang, Y.S.; Wong, X.Y.A.; Rajandran, P.; Tan, M.G.; Tan, A.L.; Tan, Y.E. First Reported Case of Trichophyton indotineae Dermatophytosis in Singapore. Pathology 2024, 56, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Kushwaha, P.; Kalsi, A.S. Tinea Universalis Due to Trichophyton indotineae in an Adult Male. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 46, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Long, X.; Hu, W.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ahmed, S.; de Hoog, G.S.; Liu, W.; Jiang, Y. The Epidemic of the Multiresistant Dermatophyte Trichophyton indotineae Has Reached China. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1113065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, M.D.; Marzouk, S.; Bećiri, L. Widespread Dermatophytosis in a Healthy Adolescent: The First Report of Multidrug-Resistant Trichophyton indotineae Infection in the UAE. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2024, 33, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.S.; Chan, J.B.; Katz, K.A. Extensive Multidrug-Resistant Dermatophytosis From Trichophyton indotineae. Cutis 2024, 113, E20–E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, L.E.; Sanglard, D.; Howard, S.J.; Rogers, P.D.; Perlin, D.S. Mechanisms of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a019752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastghaib, L.; Azizzadeh, M.; Jafari, P. Therapeutic Options for the Treatment of Tinea Capitis: Griseofulvin versus Fluconazole. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2005, 16, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassaan, Z.R.A.A.; Mohamed, H.A.K.; Eldahshan, R.M.; Elsaie, M.L. Comparison between the Efficacy of Terbinafine and Itraconazole Orally vs. the Combination of the Two Drugs in Treating Recalcitrant Dermatophytosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhai, S.; Waleed Taher, K. Voriconazole: A Review of Adjustment Programs Guided by Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1439586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart, S.R.; Smith, D.J.; Gold, J.A.W. Trichophyton indotineae and Other Terbinafine-Resistant Dermatophytes in North America. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e00903-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Xiang, Z.J.; Yang, J.H.; Wang, W.J.; Xu, Z.C.; Xiang, R.L. Adverse Effects Associated With Currently Commonly Used Antifungal Agents: A Network Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 697330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Agarwal, A.; Agrawal, D.; Panesar, S.; Ghadlinge, M.; Sardana, K.; Sethia, K.; Malhotra, S.; Chauhan, A.; Mehta, N. Effect of Different Itraconazole Dosing Regimens on Cure Rates, Treatment Duration, Safety, and Relapse Rates in Adult Patients with Tinea Corporis/Cruris: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatelli, F.; Patel, R.; Mann, P.A.; Mendrick, C.A.; Norris, C.C.; Hare, R.; Loebenberg, D.; Black, T.A.; McNicholas, P.M. In Vitro Activities of Posaconazole, Fluconazole, Itraconazole, Voriconazole, and Amphotericin B against a Large Collection of Clinically Important Molds and Yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2009–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.S.; Gold, J.A.W.; Smith, D.J.; Lipner, S.R.; Pappas, P.G.; Elewski, B. Improving Antifungal Stewardship in Dermatology in an Era of Emerging Dermatophyte Resistance. JAAD Int. 2024, 15, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.A. A Case for Antifungal Stewardship. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2018, 12, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Stewart, R.M.; Gold, J.A.W.; Chiller, T.; Sexton, D.J.; Lockhart, S.R. Will Invasive Fungal Infections Be The Last of Us? The Importance of Surveillance, Public-Health Interventions, and Antifungal Stewardship. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2023, 21, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, Y.S.; Cds, K.; Kumar, A. Comparing Emollient Use with Topical Luliconazole (Azole) in the Maintenance of Remission of Chronic and Recurrent Dermatophytosis. An Open-Label, Randomized Prospective Active-Controlled Non-Inferiority Study. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Cooper, E.A. Safety and Efficacy of a 48-Month Efinaconazole 10% Solution Treatment/Maintenance Regimen: 24-Month Daily Use Followed by 24-Month Intermittent Use. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, M.M.; Rengasamy, M.; Dogra, S.; Kaur, T.; Asokan, N.; Sarveswari, K.N.; Poojary, S.; Arora, D.; Patil, S.; Das, A.; et al. A Multicentric Clinical and Epidemiological Study of Chronic and Recurrent Dermatophytosis in India. Mycoses 2022, 65, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertagnolio, S.; Dobreva, Z.; Centner, C.M.; Olaru, I.D.; Donà, D.; Burzo, S.; Huttner, B.D.; Chaillon, A.; Gebreselassie, N.; Wi, T.; et al. WHO Global Research Priorities for Antimicrobial Resistance in Human Health. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Ray, A.; Das, A.; Panda, S. Antifungal Stewardship: What We Need to Know. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2023, 89, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, M.; Muñoz, P.; Rodríguez, C.G.; Caliz, B.; Padilla, B.; Fernández-Cruz, A.; Sánchez-Somolinos, M.; Gijón, P.; Peral, J.; Gayoso, J.; et al. Antifungal Stewardship in a Tertiary-Care Institution: A Bedside Intervention. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, e1–e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotti, S.; Cruciani, D.; Sabbatucci, M.; Spina, S.; Piscioneri, V.; Torricelli, M.; Calcaterra, R.; Farina, C.; Pisano, L.; Papini, M. Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton Strains Isolated from Humans and Animals: A Retrospective Cohort Study in Italy, 2016 to May 2024. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Versteeg, S.G. The Role of Shoe and Sock Sanitization in the Management of Superficial Fungal Infections of the Feet. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2019, 109, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaastrup, K.N.; Astvad, K.M.T.; Arendrup, M.C.; Jemec, G.B.E.; Saunte, D.M.L. Disinfection Trials with Terbinafine-Susceptible and Terbinafine-Resistant Dermatophytes. Mycoses 2022, 65, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundi, M.; Nasrallah, J.; Marteau, A.; Chebbah, D.; Izri, A.; Brun, S. Effect of Household Laundering, Heat Drying, and Freezing on the Survival of Dermatophyte Conidia. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, T.R.; Mucha, H.; Hoefer, D. Dermatophyte Susceptibility Varies towards Antimicrobial Textiles. Mycoses 2012, 55, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghannoum, M.A.; Isham, N.; Long, L. Optimization of an Infected Shoe Model for the Evaluation of an Ultraviolet Shoe Sanitizer Device. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2012, 102, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodyear, N. Effectiveness of Five-Day-Old 10% Bleach in a Student Microbiology Laboratory Setting. Am. Soc. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2012, 25, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trichophyton rubrum | Trichophyton indotineae | |

|---|---|---|

| Summary | Currently the most prominent dermatophyte worldwide. Distinguishing morphological features in KOH and culture | Terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton mentagrophytes with ITS genotype VIII May be indistinguishable from Trichophyton mentagrophytes/interdigitale complex unless sequenced |

| Common lesion sites | Tinea pedis Tinea corporis Tinea cruris Onychomycosis | Tinea corporis Tinea cruris Tinea faciei |

| Lesion characteristics | Annular, scaly plaques with central clearing Dry scaling on soles: tinea pedis Chronic, mild progression Common nail infection: thickened, discolored, brittle nails Scalp involvement uncommon | Intense pruritus Erythematous, scaly plaques Multiple concentric ring-on-ring patterns Severe, chronic, and recalcitrant lesions Nail involvement uncommon Scalp involvement uncommon |

| Response to terbinafine | Generally, responds to terbinafine, although squalene epoxidase (SQLE) mutations have been reported in resistant cases | Highly resistant to terbinafine Exhibit squalene epoxidase (SQLE) mutations and resistance to terbinafine Itraconazole or combination therapies (oral plus topical) may be required |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gupta, A.K.; Susmita; Nguyen, H.C.; Liddy, A.; Economopoulos, V.; Wang, T. Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton indotineae: A Literature Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050472

Gupta AK, Susmita, Nguyen HC, Liddy A, Economopoulos V, Wang T. Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton indotineae: A Literature Review. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(5):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050472

Chicago/Turabian StyleGupta, Aditya K., Susmita, Hien C. Nguyen, Amanda Liddy, Vasiliki Economopoulos, and Tong Wang. 2025. "Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton indotineae: A Literature Review" Antibiotics 14, no. 5: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050472

APA StyleGupta, A. K., Susmita, Nguyen, H. C., Liddy, A., Economopoulos, V., & Wang, T. (2025). Terbinafine Resistance in Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton indotineae: A Literature Review. Antibiotics, 14(5), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050472