Existing Evidence from Economic Evaluations of Antimicrobial Resistance—A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

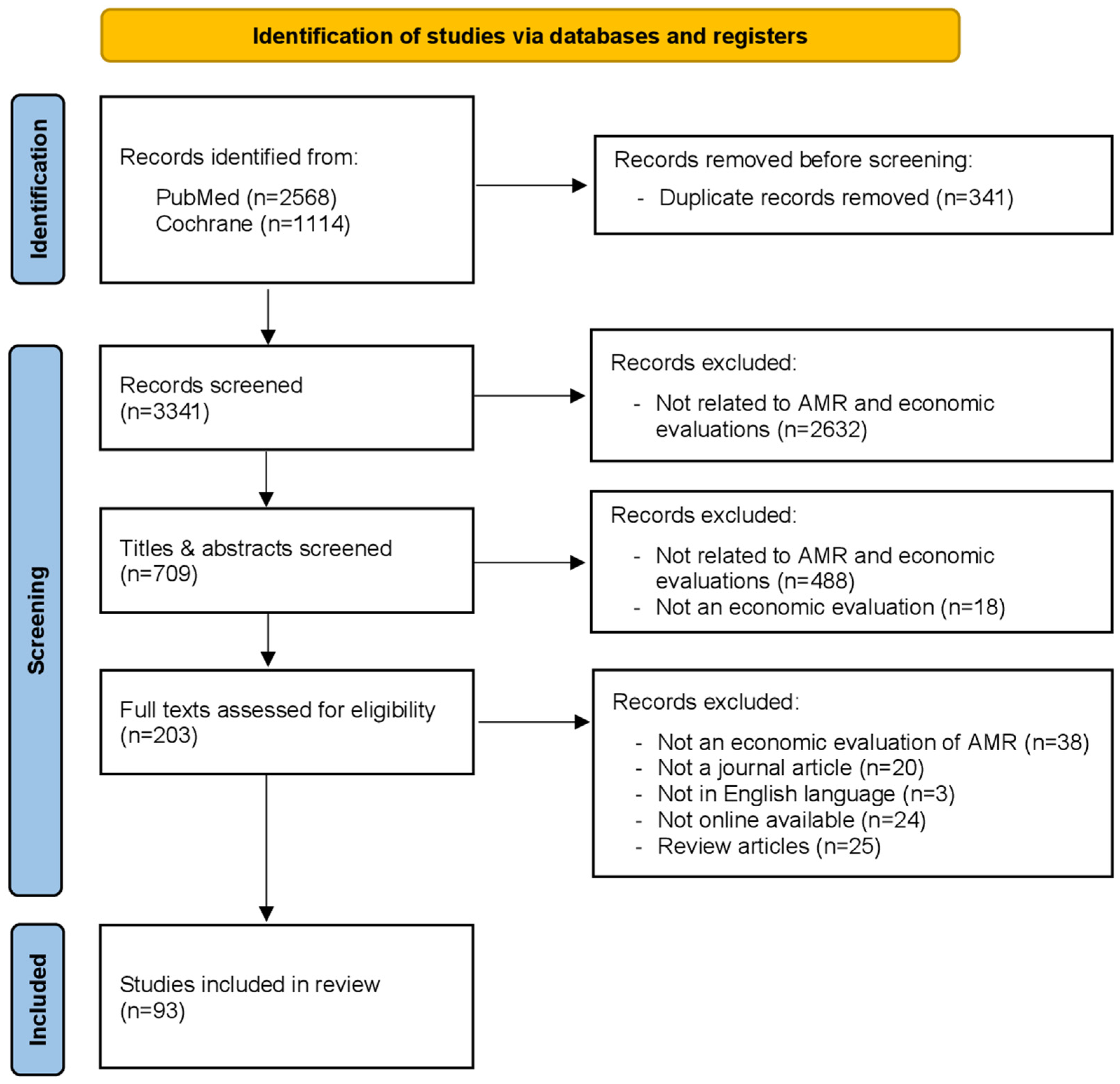

2.4. Selecting Studies

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Definitions of Economic Evaluations

2.7. Quality Assessment

2.8. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Quality Appraisal of Eligible Studies

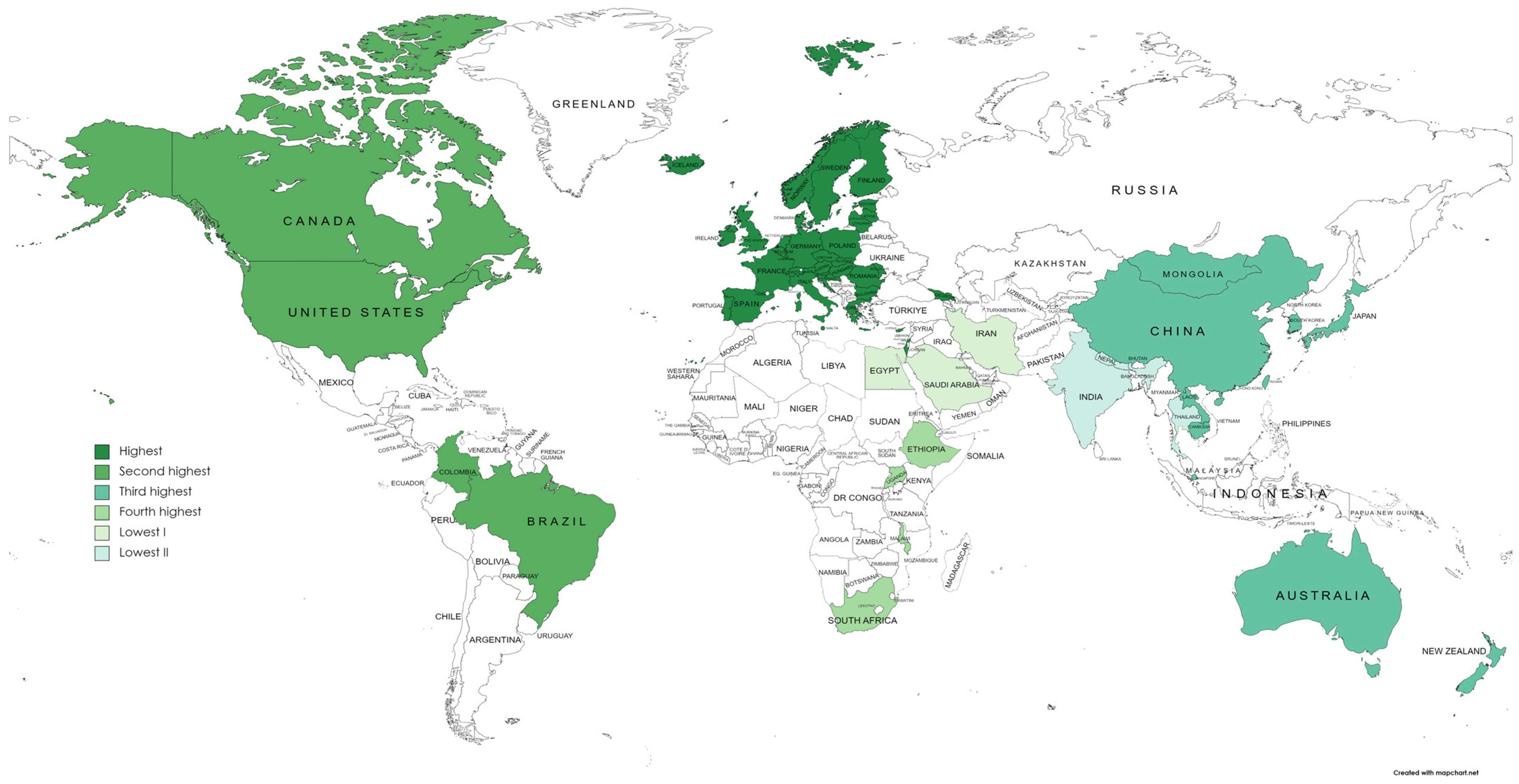

3.3. Overview of AMR Economic Evaluations

3.4. Available Evidence of Economic Evaluations of AMR

3.5. Limitations Reported in Studies of AMR-Related Economic Evaluations

3.5.1. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

3.5.2. Cost of Illness Studies

3.5.3. Other Economic Evaluations: Disease Burden Studies, Cost-Benefit Analysis, Cost-Utility Analysis, and Cost Minimization Analysis

3.6. Causes and Consequences of Study Limitations

4. Discussion

4.1. Available Evidence and the Evidence Gap in AMR Economic Evaluations

4.2. Limitations Reported in AMR Economic Evaluations and Their Interactions

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CBA | Cost–benefit analysis |

| CEA | Cost-effectiveness analysis |

| CMA | Cost minimization analysis |

| COI | Cost of illness |

| CUA | Cost–utility analysis |

| DALYs | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| HICs | High-income countries |

| Lao PDR | Lao People’s Democratic Republic |

| LICs | Low-income countries |

| LMICs | Lower- and middle-income countries |

| MeSH | Medical subject headings |

| MMAT | Mixed-methods appraisal tool |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QALYs | Quality-adjusted life years |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| WB | World Bank |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Type of Economic Evaluation | Citation (Study Conducted Year) | Infection/Ill Health Condition | Resistant Pathogen | Intervention/Treatment (Type of Antibiotic/Drug) | Sector/Setting | Value Type | Unit of Measurement | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA | Jansen et al. 2009 [21] (2006) | Diabetic foot infection |

|

| Human/Setting—no data | Lifetime QALYs | Years | Treatment I and II: 12.13 and 10.97 |

| Direct medical cost (Drug) per patient | Great British Pound (GBP) | Treatment I and II: 456.00 and 781.00 | ||||||

| Total cost | GBP | Treatment I and II: 5072.00 and 8537.00 | ||||||

| QALY savings | Years | Treatment I vs. II: 1.16 | ||||||

| Cost per QALY saved | GBP | Treatment I vs. II: 407.00 | ||||||

| Martin et al. 2008 [42] (2006) | Community-acquired pneumonia |

|

| Human/Hospital and community-based | First-line treatment failure | Percentage | Treatment I to IV: 5, 16, 19, 18 | |

| Second-line treatment failure | Percentage | Treatment I to IV: 4, 13, 16, 15 | ||||||

| Hospitalization rate | Percentage | Treatment I to IV: 1, 4, 4, 4 | ||||||

| Death rate | Percentage | Treatment I to IV: 0.01, 0.04, 0.03, 0.03 | ||||||

| Direct healthcare costs per episode | Euro | Treatment I to IV: 143.53, 221.97, 211.16, 192.79 | ||||||

| Harding-Esch et al. 2020 [43] (2015–2016) | Neisseria gonorrheae | No data | Standard care vs. Antimicrobial resistance point-of-care testing (AMR POCT);

| Human/Hospital-based | Total additional cost | GBP | 1,098,386.00/1,237,676.00/1,210,330.00/415,516.00/601,414.00 a | |

| Additional cost per patient | GBP | 28.26/31.84/31.14/10.69/15.47 a | ||||||

| Number of optimal treatments gained | Number of patients | 895/1660/1449/1002/895 a | ||||||

| Additional cost per optimal treatment gained | GBP | 1226.97/745.44/835.39/414.67/671.82 a | ||||||

| Wysham et al. 2017 [33] (2015) | Ovarian cancer | Platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer | Adding bevacizumab to single-agent chemotherapy | Human/Hospital-based | ICER associated with B + CT per QALY gained | United States Dollar (USD) | 410,455.00 | |

| ICER associated with B + CT per PF-LYS | USD | 217,080.00 | ||||||

| Cost per person (CT) | USD | 57,872.00 | ||||||

| Cost per person (B + CT) | USD | 117,568.00 | ||||||

| Incremental cost (B + CT) | USD | 59,696.00 | ||||||

| Morgans et al. 2022 [62] (2020) | Prostate cancer | Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer previously treated with docetaxel and an ARTA | Cabazitaxel (Treatment I) vs. a second androgen receptor-targeted agent (Treatment II) | Human/Hospital-based | Cost of symptomatic skeletal events | USD | Treatment I and II: 498,909.00 and 627,569.00 | |

| Cost of adverse events | USD | Treatment I and II: 276,198.00 and 251,124.00 | ||||||

| Cost of end-of-life care | USD | Treatment I and II: 808,785.00 and 1,028,294.00 | ||||||

| Hospitalization cost | USD | Treatment I and II: 1,442,870.00 and 1,728,394.00 | ||||||

| Length of hospital stay avoidable | Days | Treatment I vs. II: 58 | ||||||

| Length of ICU stay avoidable | Days | Treatment I vs. II: 2 | ||||||

| Total Cost saving | USD | Treatment I vs. II: 323,095.00 | ||||||

| Length of hospital stay | Days | Treatment I vs. II: 260 and 318 | ||||||

| Length of ICU stay | Days | Treatment I vs. II: 6 and 8 | ||||||

| Oppong et al. 2016 [32] (2012) | Lower respiratory tract infections | No data | Amoxicillin | Human/Setting—No data | Estimated threshold for the cost of resistance | GBP | 4.98 for 20,000.00 per QALY threshold, and 8.68 for 30,000.00 per QALY | |

| Difference in cost between amoxicillin and placebo groups with the inclusion of possible values for the cost of resistance | GBP | With US data = 66.09 | ||||||

| With European data = 4.42 | ||||||||

| With Global data = 218.25 | ||||||||

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (per QALY gained with the US, European, and global data, respectively) | GBP | With US data = 178,618.00 | ||||||

| With European data = 11,949.00 | ||||||||

| With Global data = 589,856.00 | ||||||||

| Yi et al. 2019 [41] (No data for the study conducted year) | Helicobacter pylori infection | No data |

| Human/Hospital-based | Total drug cost (per single treatment course) | USD | FZD = 70.05 | |

| CLA = 89.43 | ||||||||

| Effectiveness | Percentage | FZD = 93.26 | ||||||

| CLA = 87.91 | ||||||||

| Cost-effectiveness ratio | Ratio | FZD = 0.75 | ||||||

| CLA = 1.02 | ||||||||

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio | Ratio | −3.62 | ||||||

| Kirwin et al. 2019 [28] (2011–2015) | No data | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | No data | Human/Hospital and community-based | Incremental inpatient costs associated with hospital-acquired cases | Canadian dollars (CAD) | For colonization: 31,686.00 (95% CI: 14,169.00–60,158.00) | |

| For infection: 47,016.00 (95% CI: 23,125.00–86,332.00) | ||||||||

| Incremental inpatient costs associated with community-acquired cases | CAD | For colonization: 7397.00 (95% CI: 2924.00–13,180.00) | ||||||

| For infection: 14,847.00 (95% CI: 8445.00–23,207.00) | ||||||||

| Incremental length of stay—hospital-acquired infections | Days | 35.2 (95% CI: 16.3–69.5) | ||||||

| Incremental length of stay—community-acquired infections | Days | 3.0 (95% CI: 0.6–6.3) | ||||||

| Evans et al. 2007 [48] (1996–2000) | No data | Gram-negative bacteria |

| Human/Hospital-based | Hospital costs (median) | USD | 80,500.00 vs. 29,604.00 (p < 0.0001) | |

| Antibiotic costs (median) | USD | 2607.00 vs. 758.00 (p < 0.0001) | ||||||

| Hospital length of stay (median) | Days | 29 vs. 13 days (p < 0.0001) | ||||||

| Intensive care unit length of stay (median) | Days | 13 days vs. 1 day (p < 0.0001) | ||||||

| Estimated incremental increase in hospital cost [median (95% CI)] | USD | 11,075.00 (3282.00–20,099.00) | ||||||

| Pollard et al. 2017 [56] (2013) | Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | No data |

| Human/Setting—no data | Unit Cost | USD | Sip − T = 31,000.00 | |

| Enzal = 7450.00 | ||||||||

| Abir = 5390.00 | ||||||||

| Pred (10 mg daily) = 0.40 | ||||||||

| Doc = 1515.62 | ||||||||

| Rad = 11,500.00 | ||||||||

| Cabaz = 7773.00 | ||||||||

| Leup (3 mo depot) = 141.75 | ||||||||

| Deno = 1587.30 | ||||||||

| Total cost | USD | Sip − T = 98, 860.25 | ||||||

| Enzal = 61,835.00 | ||||||||

| Abir = 43,216.00 | ||||||||

| Doc = 16,235.26 | ||||||||

| Rad = 73,700.51 | ||||||||

| Cabaz = 50,038.79 | ||||||||

| Leup(3 mo depot) = 2477.46 | ||||||||

| Deno = 71,499.65 | ||||||||

| Incremental cost | USD | Sip − T = 106,117.00 | ||||||

| Sip − T + Enzal = 68,384.00 | ||||||||

| Sip − T + Enzal + Abir = 50,119.00 | ||||||||

| SipT + Enzal + Abir + Doc = 245,103.00 | ||||||||

| Sip − T + Enzal + Abir + Doc + Rad = 80,072.00 | ||||||||

| Sip − T + Enzal + Abir + Doc + Rad + Cabaz = 54,287.00 | ||||||||

| ICER | Ratio | Sip − T = 312,109.00 | ||||||

| Sip − T + Enzal = 220,594.00 | ||||||||

| Sip − T + Enzal + Abir = 151,876.00 | ||||||||

| SipT + Enzal + Abir + Doc = 207,714.00 | ||||||||

| Sip − T + Enzal + Abir + Doc + Rad = 266,907.00 | ||||||||

| Sip − T + Enzal + Abir + Doc + Rad + Cabaz = 271,435.00 | ||||||||

| Larsson et al. 2022 [25] (2015–2019) | Febrile urinary tract infections | Escherichia coli | Temocillin vs. Cefotaxime | Human/Hospital-based | Treatment cost (Temocillin, Cefotaxime, Difference) | Euro | 5,620,393.00, 443,258.00, 5,177,135.00 | |

| Healthcare costs (Temocillin, Cefotaxime, Difference) | Euro | 2,480,820.00, 4,531,007.00, −2,050,187.00 | ||||||

| Production loss costs (Temocillin, Cefotaxime, Difference) | Euro | 190,572.00, 348,063.00, −157,491.00 | ||||||

| Total costs (Temocillin, Cefotaxime, Difference) | Euro | 8,291,785.00, 5,322,328.00, 2,969,457.00 | ||||||

| QALY (Temocillin, Cefotaxime, Difference) | Years | 36,653.00, 36,576.00, 77.16 | ||||||

| ICER | Ratio (Euro/QALY) | 38,487.00 | ||||||

| Rao et al. 1988 [119] (1986–1987) | No data | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Cost of outbreak—total reimbursement to the hospital | USD | 34,415.00 | |

| Discrepancy between the cost of treatment and financial reimbursement | USD | 79,905.00 | ||||||

| Cost of MRSA eradication | USD | 9984.00 | ||||||

| Tu et al. 2021 [54] (2019) |

| No data | 12 vs. 4-Weekly Bone-Targeted Agents (BTA) | Human/Hospital-based | Total cost of treatment | Canadian dollars | 4-weekly BTA = 8965.03 | |

| 12-weekly BTA = 5671.28 | ||||||||

| Incremental = −3293.75 | ||||||||

| QALY | Years | 4-weekly BTA = 0.605 | ||||||

| 12-weekly BTA = 0.612 | ||||||||

| Incremental = 0.008 | ||||||||

| ICER (∆ cost/∆ QALY) | Descriptive | 12-weekly dominates 4-weekly | ||||||

| Incremental net benefit (INB) | Canadian dollars | 3681.37 | ||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 [120] (2006–2014) | Chronic hepatitis B with adefovir dipivoxil resistance | No data |

| Human/Hospital-based | Cost | USD | LMV + ADV = 3024.00, LdT + ADV = 3292.80, ETV + ADV = 5107.2 | |

| Cost-effectiveness ratio of negative conversion of HBV DNA | Ratio | LMV + ADV = 33.3, LdT + ADV = 35.4, ETV + ADV = 544.0 | ||||||

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of negative conversion of HBV DNA | Ratio | LdT + ADV = 134.4, ETV + ADV = 718.3 | ||||||

| Cost-effectiveness ratio of seroconversion of HBeAg/HBeAb | Ratio | LMV + ADV = 63.4, LdT + ADV = 67.5, ETV + ADV = 99.5 | ||||||

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of seroconversion of HBeAg/HBeAb | Ratio | LdT + ADV = 244.4, ETV + ADV = 578.7 | ||||||

| Cost-effectiveness ratio of nongenotypic mutation | Ratio | LMV + ADV = 31.3, LdT + ADV = 33.7, ETV + ADV = 52.4 | ||||||

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of nongenotypic mutation | Ratio | LdT + ADV = 268.8, ETV + ADV = 2314.7 | ||||||

| Tringale et al. 2018 [34] (2017) |

| No data | Nivolumab vs. Standard therapy | Human/Setting—No data | Overall cost increased (with Nivolumab) | USD | 117,800.00 | |

| Overall cost increased (with standard therapy) | USD | 178,800.00 | ||||||

| Increased effectiveness of QALYs (with Nivolumab) | Years | 0.40 | ||||||

| Increased effectiveness of QALYs (with standard therapy) | Years | 0.796 | ||||||

| ICER | Ratio | 294,400.00/QALY | ||||||

| Wolfson et al. 2015 [57] (2013) | Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis | No data | Bedaquiline plus background regimen (BR) | Human/Hospital and Community-based | Total Cost | GBP | Bedaquiline + BR = 2,170,394.00, BR only = 2,403,442.00, Incremental (Bedaquiline + BR vs. BR) = −233,048.00 | |

| Per patient cost | GBP | Bedaquiline + BR = 106,487.00, BR only = 117,922.00, Incremental (Bedaquiline + BR vs. BR) = −11,434.00 | ||||||

| Total QALYs gained | Years | Bedaquiline + BR = 105.09, BR only = 81.80, Incremental (Bedaquiline + BR vs. BR) = 23.28 | ||||||

| Per patient QALYs | Years | Bedaquiline + BR = 5.16, BR only = 4.01, Incremental (Bedaquiline + BR vs. BR) = 1.14 | ||||||

| Total DALYs lost | Years | Bedaquiline + BR = 187.80, BR only = 280.83, Incremental (Bedaquiline + BR vs. BR) = −93.04 | ||||||

| Per patient DALYs lost | Years | Bedaquiline + BR = 9.21, BR only = 13.78, Incremental (Bedaquiline + BR vs. BR) = −4.56 | ||||||

| Incremental cost per QALY gained | GBP | Bedaquiline + BR Dominates (−£10,008.75) | ||||||

| Incremental cost per DALY avoided | GBP | Bedaquiline + BR Dominates (−£2504.95) | ||||||

| Kong et al. 2023 [35] (no data for the study conducted year) | Bloodstream infection | Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Human/Hospital-based | Total Cost | USD | CAZ-AVI = 23,261,700.00, PMB = 23,053,300.00, PMB-based regimen = 25,480,000.00 | |

| QALYs | Years | CAZ-AVI = 1240, PMB = 890, PMB-based regimen = 1180 | ||||||

| Incremental cost | USD | PMB = 208,400.00, PMB-based regimen = −2218,300.00 | ||||||

| Incremental QALYs | Years | PMB = 350, PMB-based regimen = 60 | ||||||

| ICER ($/QALY) | Ratio | PMB = 591.7, PMB-based regimen = −36,730.9 (Dominated) | ||||||

| Mullins et al. 2006 [36] (2002–2003) | Nosocomial pneumonia | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Linezolid vs. Vancomycin | Human/Hospital-based | Treatment cost (per day)—median | USD | Linezolid = 2888.00, Vancomycin = 2993.00 | |

| Total hospitalization cost | USD | Linezolid = 32,636.00, Vancomycin = 32,024.00 | ||||||

| ICER for linezolid per life saved | USD | 3600.00 | ||||||

| Mean treatment durations | Days | Linezolid = 11.3, Vancomycin = 10.7 | ||||||

| Jansen et al. 2009 [30] (2006) | Complicated intraabdominal infections (IAI) | No data | Ertapenem vs. Piperacillin/Tazobactam | Human/Hospital-based | Overall savings per patient (95% uncertainty interval) | Euro | 355.00 (480.00–1205.00) | |

| Cost savings with ertapenem—estimated increase (95% uncertainty interval) | Euro | 672.00 (232.00–1617.00) | ||||||

| QALYs (95% uncertainty interval) | Years | 0.17 (0.07–0.30) | ||||||

| Fawsitt et al. 2020 [37] (2017–2018) | Genotype 1 noncirrhotic treatment-naive patients | Hepatitis C Virus (HPV) | Nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) | Human/Hospital-based | Incremental net monetary benefit (INMB) | GBP | Baseline testing vs. standard 12 weeks of therapy = 11,838.00 | |

| Shortened 8 weeks of treatment (no testing) = 12,294.00 | ||||||||

| Sado et al. 2021 [44] (2008–2013) | Pharmacotherapy-resistant depression | No data | Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) vs. Treatment as usual (TAU) | Human/Hospital-based | ICER (CBT vs. TAU) | USD (per QALY) | All patients (n = 73): −142,184.00 1.2. Moderate/severe patients (n = 50): 18,863.00 | |

| Incremental costs (95% CI) | USD | All patients (n = 73): 905.00 (408.00–1394.00) | ||||||

| USD | Moderate/severe patients (n = 50): 785.00 (267.00–1346.00) | |||||||

| Cara et al. 2018 [55] (2011–2014) | Nosocomial pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria | Gram-negative pathogen | Low- (LDC) vs. High-dose colistin (HDC) | Human/Hospital-based | Average total direct costs per episode of colistin treatment | Saudi Arabian Riyal (SAR) | LDC: 24,718.42 | |

| HDC: 27,775.25 | ||||||||

| Incremental cost (per nephrotoxicity avoided) | SAR | 3056.28 | ||||||

| Weinstein et al. 2001 [23] (No data for the study conducted year) | Genotypic resistance—HIV infection | No data | No data | Human/Community-based | CPCRA trial—Cost of no genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing | USD | 90,360.00 | |

| CPCRA trial—Cost of Genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing | USD | 93,650.00 | ||||||

| VIRADAPT trial—Cost of no genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing | USD | 91,980.00 | ||||||

| VIRADAPT trial—Cost of Genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing | USD | 97,790.00 | ||||||

| CPCRA trial—Cost-effectiveness ratio of Genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing | USD/QALY gained | 17,900.00 | ||||||

| VIRADAPT trial—Cost-effectiveness ratio of Genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing | USD/QALY gained | 16,300.00 | ||||||

| Barbieri et al. 2005 [121] (2000) | Rheumatoid arthritis | No data | Infliximab plus methotrexate (MTX) vs. MTX alone | Human/Community-based | Primary analysis (Incremental cost, Incremental QALYs, and Incremental cost/QALYs, respectively) | GBP, Years, and Ratio, respectively | 8576.00, 0.26, 33,618.00 | |

| Radiographic progression analysis (Incremental cost, Incremental QALYs, and Incremental cost/QALYs, respectively) | 7835.00, 1.53, 5111.00 | |||||||

| Intent-to-treat analysis (Incremental cost, Incremental QALYs, and Incremental cost/QALYs, respectively) | 14,635.00, 0.40, 36,616.00 | |||||||

| Lifetime analysis (Incremental cost, Incremental QALYs, and Incremental cost/QALYs, respectively) | 30,147.00, 1.26, 23,936.00 | |||||||

| Marseille et al. 2020 [46] (2004–2017) | Chronic treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder | No data |

| Human/Hospital-based | Net costs (1 year) | USD | 7,608,691.00 | |

| QALYs | Years | 288 | ||||||

| Cost per QALY gained | USD | 26,427.00 | ||||||

| MAP intervention cost | 7543.00 | |||||||

| QALYs savings | Years | 2517 | ||||||

| Mac et al. 2019 [47] (2017) | No data | Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Incremental QALYs for VRE screening and isolation | Years | 0.0142 | |

| Incremental cost for VRE screening and isolation | Canadian dollars | 112.00 | ||||||

| ICER | Canadian dollars/per QALY | 7850.00 | ||||||

| Wassenberg et al. 2010 [22] (2001–2004) | Nosocomial infections | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | No data | Human/Hospital-based | 0% of Attributable mortality | Life years gained, discounted (in the replacement scenario)—Years | 0 | |

| 10% of Attributable mortality | 7.0 | |||||||

| 20% of Attributable mortality | 15.7 | |||||||

| 30% of Attributable mortality | 26.8 | |||||||

| 40% of Attributable mortality | 41.7 | |||||||

| 50% of Attributable mortality | 62.3 | |||||||

| 0% of Attributable mortality | Cost per life year gained per year MRSA policy (in the replacement scenario)—Euro | Not applicable | ||||||

| 10% of Attributable mortality | 45,912.00 | |||||||

| 20% of Attributable mortality | 21,357.00 | |||||||

| 30% of Attributable mortality | 13,165.00 | |||||||

| 40% of Attributable mortality | 9062.00 | |||||||

| 50% of Attributable mortality | 6590.00 | |||||||

| Papaefthymiou et al., 2019 [63] (2012–2016) | Helicobacter pylori infection | Helicobacter pylori |

| Human/Hospital-based | Cost-effectiveness analysis ratio (CEAR)—10-day concomitant regimen with esomeprazole (Lowest) | Euro | 179.17 | |

| CEAR—10-day concomitant regimen with pantoprazole | 183.27 | |||||||

| CEAR—Hybrid regimen (Higher) | 187.42 | |||||||

| CEAR—10-day sequential use of pantoprazole | 204.12 | |||||||

| CEAR—10-day sequential use of esomeprazole | 216.02 | |||||||

| Bhavnani et al. 2009 [122] (2002–2005) | No data | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Daptomycin vs. Vancomycin-gentamicin | Human/Hospital-based | Stratum I—for daptomycin | USD | 4082.00 (1062.00–13,893.00) | |

| Stratum I—for vancomycin-gentamicin | 560.00 (66.00–1649.00) | |||||||

| Stratum II—for daptomycin | 4582.00 (1109.00–21,882.00) | |||||||

| Stratum II—for vancomycin-gentamicin | 1635.00 (163.00–33,444.00) | |||||||

| Stratum III—for daptomycin | 23,639.00 (6225.00–141,132.00) | |||||||

| Stratum III—for vancomycin-gentamicin | 26,073.00 (5349.00–187,287.00) | |||||||

| Hollinghurst et al. 2014 [39] (2008–2010) | Treatment-resistant depression | No data | Cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) | Human/Hospital-based | Mean cost of CBT per participant | GBP | 910.00 | |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio | GBP | 14,911.00 | ||||||

| Martin et al. 2007 [38] (2006) | Community-acquired pneumonia |

|

| Human/Community-based | Moxifloxacin/coamoxiclav | Total cost in France—Euro | 161.40 | |

| Clarithromycin/moxifloxacin | 276.56 | |||||||

| Coamoxiclav/clarithromycin | 278.64 | |||||||

| Moxifloxacin/coamoxiclav | Total cost in USA —USD | 719.86 | ||||||

| Azithromycin/moxifloxacin | 876.33 | |||||||

| Coamoxiclav/azithromycin | 881.94 | |||||||

| Doxycycline/azithromycin | 908.01 | |||||||

| Moxifloxacin/coamoxiclav | Total cost in Germany—Euro | 240.60 | ||||||

| Roxithromycin/moxifloxacin | 250.59 | |||||||

| Amoxicillin/roxithromycin | 268.91 | |||||||

| Cefuroxime axetil/moxifloxacin | 314.33 | |||||||

| Xiridou et al., 2016 [26] (2016) | Gonococcal infections | Neisseria gonorrheae | Dual therapy (Ceftriaxone and Azithromycin) vs. Monotherapy (Ceftriaxone) | Human/Hospital-based | Annual cost | Euro | 112,853.00 | |

| Annual QALYs | Years | 0.000174 | ||||||

| Annual ICER | Ratio | 1.91 × 108 | ||||||

| Cumulative costs | Euro | 1,355,146.00 | ||||||

| Cumulative QALYs | Years | 0.000495 | ||||||

| Cumulative ICER | Ratio | 9.74 × 108 | ||||||

| Resistance—monotherapy | Percentage | 0.01 | ||||||

| Resistance—Dual therapy | Percentage | 0 (Zero) | ||||||

| Liao et al., 2019 [51] (2019) | Metastatic breast cancer | No data | Utidelone plus Capecitabine vs. Capecitabine alone | Human/Community-based | Incremental Cost | USD | 13,370.25 | |

| QALYs | Years | 0.1961 | ||||||

| ICER per QALY | USD | 68,180.78 | ||||||

| Machado et al., 2005 [60] (2005) | Ventilation-associated nosocomial pneumonia | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Linezolid vs. Vancomycin | Human/Hospital-based | Vancomycin | The per unit cost —USD | 47.73 | |

| Generic vancomycin | 14.45 | |||||||

| Linezolid | 214.04 | |||||||

| Linezolid | Efficacy in VAP-MRSA—Percentage | 62.2 | ||||||

| Vancomycin | 21.2 | |||||||

| Vancomycin | The total cost per cured patient—USD | 13,231.65 | ||||||

| Generic vancomycin | 11,277.59 | |||||||

| Linezolid | 7764.72 | |||||||

| Xin et al., 2020 [58] (2020) |

| No data | Pembrolizumab vs. Standard-of-care (SOC) | Human/Hospital-based | Total mean cost—Pembrolizumab | USD | 45,861.00 | |

| Total mean cost—SOC | USD | 41,950.00 | ||||||

| QALYs gained—Pembrolizumab | Years | 0.31 | ||||||

| QALYs gained—SOC | Years | 0.25 | ||||||

| ICER | Ratio [USD] | 65,186.00/QALY | ||||||

| Wan et al., 2016 [27] (2016) | Nosocomial pneumonia | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Linezolid vs. Vancomycin | Human/Hospital-based | Beijing—Treatment cost (linezolid vs. vancomycin) | Chinese Yuan | 79,551.00 (95% CI ¼ 72,421.00–86,680.00) vs. 77,587.00 (70,656.00–84,519.00) | |

| Beijing—ICER (linezolid over vancomycin) | Ratio (Chinese Yuan) | 19,719.00 (143,553.00 to 320,980.00) | ||||||

| Guangzhou—Treatment cost (linezolid vs. vancomycin) | Chinese Yuan | 90,995.00 (82,598.00–99,393.00) vs. 89,448.00 (81,295.00–97,601.00) | ||||||

| Guangzhou—ICER (linezolid over vancomycin) | Ratio (Chinese Yuan) | 15,532.00 (185,411.00 to 349,693.00) | ||||||

| Nanjing—Treatment cost (linezolid vs. vancomycin) | Chinese Yuan | 82,383.00 (74,956.00–89,810.00) vs. 80,799.00 (73,545.00–88,054.00) | ||||||

| Nanjing—ICER (linezolid over vancomycin) | Ratio (Chinese Yuan) | 15,904.00 (161,935.00 to 314,987.00) | ||||||

| Xi’an—Treatment cost (linezolid vs. vancomycin) | Chinese Yuan | 59,413.00 (54,366.00–64,460.00) vs. 57,804.00 (52,613.00–62,996.00) | ||||||

| Xi’an—ICER (linezolid over vancomycin) | Ratio (Chinese Yuan) | 16,145.00 (100,738.00 to 234,412.00) | ||||||

| Liu et al., 2021 [45] (2021) | Chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection (HCV GT 1b)—Nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) resistance | No data | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Overall increase in total healthcare cost | USD | 13.50 | |

| Overall increase in QALYs | Years | 0.002 | ||||||

| ICER | Ratio (USD/QALY) | 6750/QALY gained | ||||||

| Breuer and Graham, 1999 [61] (1999) | Helicobacter pylori Infection | Helicobacter pylori | Endoscopy plus biopsy followed by empirical antibiotic treatment of H. pylori-positive ulcer patients. | Human/Setting—No data | Cost saving per 1000 patients treated (Treatment A) | USD | 37,000.00 | |

| Additional cost per 1000 patients treated | 8027.00 | |||||||

| Niederman et al., 2014 [29] (2014) | Nosocomial pneumonia | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| Human/Hospital-based | Total treatment cost for patients without renal failure | USD | 44,176.00 | |

| Total treatment cost for patients with renal failure | 52,247.00 | |||||||

| Total treatment cost difference (for patients who developed renal failure compared with those who did not) | 8000.00 | |||||||

| Cost-effectiveness ratio (for linezolid compared with vancomycin)—per treatment success | 16,516.00 | |||||||

| Lowery et al., 2013 [123] (2013) | Recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer | No data | Routine care vs. routine care plus early referral to a palliative medicine specialist (EPC) | Human/Hospital-based | Cost savings (associated with EPC) | USD | 1285.00 | |

| ICER | Ratio: USD/QALY | 37,440.00/QALY | ||||||

| Base case mean cost (EPC group) | USD | 5017.00 | ||||||

| Base case mean cost (routine group) | USD | 6303.00 | ||||||

| Chappell et al., 2016 [124] (2016) | Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer | No data |

| Human/Hospital-based | Cost (CHEMO) | USD | 21,611.00 | |

| Cost (CHEMO + BEV) | USD | 66,511.00 | ||||||

| Progression-free survival (CHEMO) | Months | 3.4 | ||||||

| Progression-free survival (CHEMO + BEV) | Months | 6.7 | ||||||

| ICER | Ratio [Cost/progression-free life-year saved (USD/PF-LYS)] | 160,000.00 | ||||||

| Human/Hospital-based | Cost (CHEMO) | USD | 18,857.00 | ||||

| Cost (CHEMO + BEV) | USD | 48,861.00 | ||||||

| Progression-free survival (CHEMO) | Months | 3.4 | ||||||

| Progression-free survival (CHEMO + BEV) | Months | 6.7 | ||||||

| ICER | Ratio (USD/PF-LYS) | 100,000.00 | ||||||

| Reed et al., 2009 [52] (2009) | Metastatic breast cancer (Progressing after anthracycline and taxane treatment) | No data | Ixabepilone Plus Capecitabine | Human/Hospital-based | For patients receiving ixabepilone plus capecitabine | USD | 60,900.00 | |

| For patients receiving capecitabine alone | 30,000.00 | |||||||

| The estimated life expectancy gain with ixabepilone | Months | 1.96 (95% CI, 1.36–2.64) | ||||||

| The estimated gain in quality-adjusted survival | Months | 1.06 (95% CI, 0.09–2.03) | ||||||

| The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per QALY | USD | 359,000.00 (95% CI, 183,000.00–4,030,000.00) | ||||||

| Ross and Soeteman et al., 2020 [40] (2020) | Treatment-resistant depression | No data | Esketamine Nasal Spray | Human/Hospital-based | QALY gained | Years | 0.07 | |

| Healthcare cost | USD | 16,995.00 | ||||||

| Base case ICER—Societal | Ratio (USD/QALY) | 237,111.00/QALY | ||||||

| Base case ICER—healthcare sector | Ratio (USD/QALY) | 242,496.00/QALY | ||||||

| Simpson et al., 2009 [59] (2009) | Pharmacotherapy-resistant major depression | No data | Antidepressant therapy—Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) | Human/Hospital-based | Cost per treatment session—sham treatment | USD | 300.00 | |

| ICER associated with TMS | 34, 999.00/per QALY | |||||||

| ICER (including productivity gains due to clinical recovery) | 6667.00/per QALY | |||||||

| Net cost savings (associated with TMS | 1123.00 per QALY | |||||||

| Net cost savings (including productivity losses) | 7621.00 | |||||||

| Phillips et al., 2023 [53] (2023) | No data | Multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhi | Typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs)—When an outbreak occurs over the 10-year time horizon | Human/Community-based | Expected net cost for reactive vaccination (routine + campaign) | USD | 1.1. 111,213.00 | |

| Expected net cost for no vaccination (base case) | 1.2. 128,360.00 | |||||||

| Expected net cost for preventative vaccination (routine + campaign) | 131,749.00 | |||||||

| Expected net cost for preventative vaccination (routine only) | 154,148.00 | |||||||

| Typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs)—When no outbreak occurs (preoutbreak incidence) | Human/Community-based | Expected net cost for no vaccination (base case) | USD | 5893.00 | ||||

| Expected net cost for preventative vaccination (routine only) | 26,704.00 | |||||||

| Expected net cost for preventative vaccination (routine + campaign) | 27,109.00 | |||||||

| Typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs)—When an outbreak has already occurred (postoutbreak incidence) | Human/Community-based | Expected net cost for no vaccination (base case) | USD | 7242.00 | ||||

| Expected net cost for preventive vaccination (routine + campaign) | 49,406.00 | |||||||

| Expected net cost for preventative vaccination (routine only) | 51,717.00 | |||||||

| Cock et al., 2009 [24] (2009) | Nosocomial pneumonia | Suspected methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Linezolid vs. Vancomycin | Human/Hospital-based | Average total costs per episode (linezolid vs. vancomycin) | Euro | 12,829.00 vs. 12,409.00 | |

| Death rate (linezolid vs. vancomycin) | Percentage | 20.7 vs. 33.9 | ||||||

| Life-years gained (linezolid vs. vancomycin) | Years | 14.0 life-years vs. 11.7 life-years | ||||||

| Incremental costs (linezolid vs. vancomycin) | Euro | 3171.00 vs. 4813.00 | ||||||

| Mean length of stay | Days | 11.2 vs. 10.8 days | ||||||

| Lynch et al., 2011 [64] (2011) | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant depression | Combined cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and medication switch vs. medication switch only | Combined Therapy vs. Medication | Human/Hospital-based | Additional depression-free days (DFDs) | Days | 8.3 | |

| DFD QALYs | Years | 0.020 | ||||||

| Depression-improvement days (DIDs) | Days | 11.0 | ||||||

| Cost per DFD/ICER | USD | 188.00 | ||||||

| Gordon et al. 2023 [49] (2021) |

| Drug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) |

| Human/Hospital-based | Hospital length of stay—Reduction in AMR levels (10%) | Days | 509,568 | |

| Hospitalization costs—Reduction in AMR levels (10%) | 593,282,404.00 | |||||||

| Life-years lost—Reduction in AMR levels (10%) | 27,093 | |||||||

| QALYs lost—Reduction in AMR levels (10%) | 23,876 | |||||||

| Hospital length of stay—Reduction in AMR levels (20%) | AUD | 508,617 | ||||||

| Hospitalization costs—Reduction in AMR levels (20%) | 592,173,849.00 | |||||||

| Life-years lost—Reduction in AMR levels (20%) | 29,575 | |||||||

| QALYs lost—Reduction in AMR levels (20%) | 22,903 | |||||||

| Hospital length of stay—Reduction in AMR levels (50%) | Years | 505,762 | ||||||

| Hospitalization costs—Reduction in AMR levels (50%) | 588,847,600.00 | |||||||

| Life-years lost—Reduction in AMR levels (50%) | 22,692 | |||||||

| QALYs lost—Reduction in AMR levels (50%) | 20,045 | |||||||

| Hospital length of stay—Reduction in AMR levels (95%) | Years | 501,479 | ||||||

| Hospitalization costs—Reduction in AMR levels (95%) | 583,856,587.00 | |||||||

| Life-years lost—Reduction in AMR levels (95%) | 17,972 | |||||||

| QALYs lost—Reduction in AMR levels (95%) | 15,396 | |||||||

| Rosu et al., 2023 [50] (2023) | Rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis | No data |

| Human/Hospital-based | Total provider cost—Ethiopia (oral/6 months/control) | USD | 3378.10/2549.00/2876.60 | |

| Total Provider cost—India (oral/6 months/control) | 1628.00/1374.70/1422.10 | |||||||

| Total Provider cost—Moldova (oral/control) | 3362.90/3128.90 | |||||||

| Total Provider cost—Uganda (oral/control) | 5437.90/4712.50 | |||||||

| Total participant cost—Ethiopia (oral/6 months/control) | 2247.80/893.70/1586.90 | |||||||

| Total participant cost—India (oral/6 months/control) | 1415.70/1293.60/1427.80 | |||||||

| Total participant cost—Moldova (oral/control) | 7059.10/11,658.60 | |||||||

| Total participant cost—Uganda (oral/control) | 2176.20/2787.50 | |||||||

| Total societal cost—Ethiopia (Oral/6 months/Control) | 5625.90/3442.70/4463.50 | |||||||

| Total societal cost—India (Oral/6 months/Control) | 3079.70/2668.00/2849.90 | |||||||

| Total societal cost—Moldova (Oral/Control) | 10,422.00/14,787.50 | |||||||

| Total societal cost—Uganda (Oral/Control) | 7614.10/7500.00 | |||||||

| QALYs—Ethiopia (Oral/6 months/Control) | Years | 0.8981/0.9002/0.9050 | ||||||

| QALYs—India (Oral/6 months/Control) | 0.7439/0.7932/0.7644 | |||||||

| QALYs—Moldova (Oral/Control) | 0.9627/0.9235 | |||||||

| QALYs—Uganda (Oral/Control) | 0.6937/0.7343 | |||||||

| Matsumoto et al., 2021 [31] (2021) |

| Drug-resistant Gram-negative pathogen: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Piperacillin/tazobactam (first-line treatment) or meropenem (second-line treatment) | Human/Community-based | Life year savings | Years | 4249,096 | |

| QALY savings | Years | 3,602,311 | ||||||

| Bed days savings | Days | 4,422,284 | ||||||

| Saved hospitalization cost | Japan Yen (USD) | 117.6 billion (1.1 billion) | ||||||

| Net monitory benefit | Japan Yen | 18.1 trillion (169.8 billion) | ||||||

| COI | McCollum et al. 2007 [70] (2003) | Complicated Skin and soft-tissue infections (cSSTIs) | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| Human/Hospital-based | Hospitalization cost | USD | Treatment I: 4510.00 |

| Treatment II: 6478.00 | ||||||||

| Total cost | USD | Treatment I: 6009.00 | ||||||

| Treatment II: 7329.00 | ||||||||

| Lenth of stay | Days | Treatment I: 6.8 | ||||||

| Treatment II: 10.3 | ||||||||

| Cure rate of MRSA group | Percentage | Treatment I: 80.0 | ||||||

| Treatment II: 71.4% | ||||||||

| Length of stay reduction (Treatment I vs. II) | Days | 3.5 | ||||||

| Duration of intravenous treatment | Days | Treatment I: 1.4 | ||||||

| Treatment II: 10.9 | ||||||||

| Duration of intravenous treatment reduction (Treatment I vs. II) | Days | 9.5 | ||||||

| Touat et al. 2019 [76] (2015) | 13 Acute infections b | Nine pathogens c | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Total cost | Euro | 109.3 million | |

| Cost per stay (mean) | Euro | 1103.00 | ||||||

| Excess length of stay (mean) | Days | 1.6 | ||||||

| Wely et al. 2004 [87] (1998–2001) | Infertility | Clomiphene citrate-resistant polycystic ovary syndrome | Laparoscopic electrocautery strategy (Treatment I) vs. Ovulation induction-Recombinant FSH (Treatment II) | Human/Hospital-based | Direct cost (mean) | Euro | Treatment I and II: 4664. and 5418.00 | |

| Indirect cost (mean) | Treatment I and II: 644.00 and 507.00 | |||||||

| Total cost (mean) | Treatment I and II: 5308.00 and 5925.00 | |||||||

| Patel et al. 2014 [86] (2012) | Nosocomial pneumonia | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Linezolid (Treatment I) vs. Vancomycin (Treatment II) | Human/Hospital-based | Direct cost (medical and drug) | Euro | Treatment I and II: 15,116.00 and 15,239.00 | |

| ICER [favored Treatment I (VS Treatment II)] | 123.00 | |||||||

| Total cost per successfully treated patient | Treatment I and II: 24,039.00 and 25,318.00 | |||||||

| Roberts et al. 2021 [81] (2019) | No data |

| No data | Human/Setting—no data | Cost of establishing a laboratory (for capacity of 10,000 specimens) per year | USD (Range) | 254,000.00–660,000.00 | |

| Cost for laboratory processing (100,000 specimens) per year | 394,000.00–887,000.00 | |||||||

| Cost per specimen | 22.00–31.00 | |||||||

| The cost per isolate (10,000 specimens) | 215.00—304.00 | |||||||

| The cost per isolate (100,000 specimens) | 105.00–122.00 | |||||||

| Song et al. 2022 [72] (2017) | Multidrug-resistant organisms’ bacteremia |

| No data | Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | Reported cases (MRSA, MRAB, MRPA, CRE, and VRE) | Number of patients | 260, 87, 18, 20, and 101 | |

| 90-day mortality rates (MRSA, MRAB, MRPA, CRE, and VRE) | Percentage | 30.4, 63.2, 16.7, 55.0, and 47.5 | ||||||

| Additional costs caused by bacteremia (MRSA, MRAB, MRPA, CRE, and VRE) | USD | 15,768.00, 35,682.00, 39,908.00, 72,051.00, and 33,662.00 | ||||||

| Estimated bacteremia cases (annual)/(MRSA, MRAB, MRPA, CRE, and VRE) | Number of patients | 4070, 1396, 218, 461, and 1834 | ||||||

| Estimated deaths (annual)/(MRSA, MRAB, MRPA, CRE, and VRE) | Number of deaths | 1237, 882, 36, 254, and 871 | ||||||

| Estimated cost (annual)/(MRSA, MRAB, MRPA, CRE, and VRE) | USD | 84,707,359.00, 74,387,364.00, 10,344,370.00, 45,850,215.00, and 79,215,694.00 | ||||||

| Estimated total cases (annual)/(for all 5 resistant pathogens) | Number of patients | 7979 | ||||||

| Estimated total deaths (annual)/(for all 5 resistant pathogens) | Number of deaths | 3280 | ||||||

| Estimated total cost (annual)/(for all 5 resistant pathogens) | USD | 294,505,002.00 | ||||||

| Length of stay (MRSA, MSSA, MRAB, Non-MDR ABA, MRPA, Non-MDR PAE, CRE, Susceptible Enterobacteriaceae, VRE, Susceptible Enterococcus) | Days | 29.8, 28.8, 30.2, 27.9, 41.6, 27.3, 55.4, 21.3, 48.2, 41.3 | ||||||

| Hospital cost (MRSA, MSSA, MRAB, Non-MDR ABA, MRPA, Non-MDR PAE, CRE, Susceptible Enterobacteriaceae, VRE, Susceptible Enterococcus) | USD | 16,386.00, 15,297.00, 24,452.00, 16,946.00, 26,168.00, 17,447.00, 73,248.00, 14,998.00, 47,779.00, 33,365.00 | ||||||

| LOS difference (MRSA vs. MSSA, MRAB vs. Non-MDR ABA, MRPA vs. Non-MDR PAE, CRE vs. Susceptible Enterobacteriaceae, VRE vs. Susceptible Enterococcus) | Days | 1.0, 2.3, 14.3, 34.1, 6.8 | ||||||

| Hospital cost difference (MRSA vs. MSSA, MRAB vs. Non-MDR ABA, MRPA vs. Non-MDR PAE, CRE vs. Susceptible Enterobacteriaceae, VRE vs. Susceptible Enterococcus) | USD | 1089.00, 7507.00, 8721.00, 58,250.00, 14,414.00 | ||||||

| Zhen et al. 2020a [65] (2013–2015) | No data |

| No data | Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | Total Hospital Cost (CRKP vs. CSKP, CRPA vs. CSPA, and CRAB vs. CSAB) | USD | 14,252.00, 4605.00, and 7277.00 | |

| Length of stay (CRKP vs. CSKP, CRPA vs. CSPA, and CRAB vs. CSAB) | Days | 13.2, 5.4, and 15.8 | ||||||

| Hospital mortality rate | Percentage difference | Between CRKP and carbapenem-susceptible K. pneumoniae (CSKP) = 2.94% | ||||||

| Between CRAB and carbapenem-susceptible A. baumannii (CSAB) = 4.03 | ||||||||

| Between CRPA and Carbapenem-susceptible P. aeruginosa (CSPA) = 2.03 | ||||||||

| Zhen et al. 2020b [89] (2013–2015) | No data |

| No data | Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | Total hospital cost [Excluding length of stay (LOS) before culture]—Median: (3GCSEC, 3GCREC, 3GCSKP, and 3GCRKP) | USD | 3867.00, 5233.00, 8084.00, and 15,754.00 | |

| Total hospital cost (Including LOS before culture)–Median: (3GCSEC, 3GCREC, 3GCSKP, and 3GCRKP) | USD | 4057.00, 5197.00, 9699.00, and 14,463.00 | ||||||

| LOS (excluding LOS before culture | Days | 16, 20, 20, 31 | ||||||

| LOS (including LOS before culture) | Days | 17, 19.5, 23, 30 | ||||||

| Mortality rate (excluding LOS before culture) | Percentage | 2.15, 2.7, 3.65, 6.74 | ||||||

| Mortality rate (including LOS before culture) | Percentage | 2.16, 2.49, 3.81, 6.51 | ||||||

| Total hospital cost difference (excluding LOS before culture) | USD | 3GCREC vs. 3GCSEC = 1366.00 | ||||||

| 3GCRKP vs. 3GCSKP = 7671.00 | ||||||||

| Total hospital cost difference (including LOS before culture) | USD | 3GCREC vs. 3GCSEC = 1140.00 | ||||||

| 3GCRKP vs. 3GCSKP = 4763.00 | ||||||||

| Total LOS difference (excluding LOS before culture) | Days | 3GCREC vs. 3GCSEC = 4 | ||||||

| 3GCRKP vs. 3GCSKP = 11 | ||||||||

| Total LOS difference (including LOS before culture) | Days | 3GCREC vs. 3GCSEC = 2.5 | ||||||

| 3GCRKP vs. 3GCSKP = 7 | ||||||||

| Mortality rate difference (excluding LOS before culture) | Percentage | 3GCREC vs. 3GCSEC = 0.55 | ||||||

| 3GCRKP vs. 3GCSKP = 3.09 | ||||||||

| Mortality rate difference (including LOS before culture) | Percentage | 3GCREC vs. 3GCSEC = 0.33 | ||||||

| 3GCRKP vs. 3GCSKP = 2.7 | ||||||||

| Girgis et al. 1995 [125] (No data for the study conducted year) | No data | Multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhi septicemia |

| Human/Hospital-based | Drug cost (Per day)—(Cefixime, Ceftriaxone, and Aztreonam) | Egyptian pounds | 22.00, 100.00, and 200.00 | |

| Drug delivery cost (Per day)—(Cefixime, Ceftriaxone, and Aztreonam) | 2. 2.00, 4.00, and 12.00 | |||||||

| Hospital stay cost (Per day)—(Cefixime, Ceftriaxone, and Aztreonam) | 3. 68.00, 68.00, and 68.00 | |||||||

| Total cost (Per day)—(Cefixime, Ceftriaxone, and Aztreonam) | 4. 92.00, 172.00, and 280.00 | |||||||

| Drug cost (Total)—(Cefixime, Ceftriaxone, and Aztreonam) | 5. 308.00, 500.00, and 1400.00 | |||||||

| Drug delivery cost (Total)—(Cefixime, Ceftriaxone, and Aztreonam) | 6. 28.00, 20.00, and 84.00 | |||||||

| Hospital stay cost (Total)—(Cefixime, Ceftriaxone, and Aztreonam) | 7. 952.00, 340.00, and 476.00 | |||||||

| Total cost (Total)—(Cefixime, Ceftriaxone, and Aztreonam) | 8. 1288.00, 860.00, and 1960.00 | |||||||

| Rijt et al. 2018 [77] (2011–2016) | No data | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Cost per patient per day (median) | Euro | 83.80 | |

| Cost per patient per day (Range) | 16.89–1820.09 | |||||||

| Naylor et al. 2020 [67] (2017) | Bloodstream infection | Antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections |

| Human/Hospital-based | Excess cost | International Dollars (2017) | Per infection = 6392.00 | |

| Per infection associated with Oxacillin resistance = 8155.00 | ||||||||

| Per infection associated with Gentamicin resistance = 5675.00 | ||||||||

| Excess length of stay | Days | SA BSI = 11.6 | ||||||

| SA BSI resistant to 1st generation Cephalosporins = 13.7 | ||||||||

| SA BSI resistant to Carbapenems = 13.7 | ||||||||

| SA BSI resistant to Gentamicin = 10.3 | ||||||||

| SA BSI resistant to Fluroquinolones = 11.6 | ||||||||

| SA BSI resistant to Penicillins = 12.9 | ||||||||

| SA BSI resistant to Oxacillin = 14.8 | ||||||||

| Browne et al. 2016 [68] (2012) | No data | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia-infective endocarditis |

| Human/Hospital-based | Drug cost (per patient) | GBP | Daptomycin = 3404.00 | |

| Vancomycin = 1991.00 | ||||||||

| Incremental costs = 1413.00 | ||||||||

| Monitoring cost (per patient) | GBP | Daptomycin = 226.00 | ||||||

| Vancomycin = 372.00 | ||||||||

| Incremental costs = −146.00 | ||||||||

| Hospital cost (per patient) | GBP | Daptomycin = 14,252.00 | ||||||

| Vancomycin = 14,796.00 | ||||||||

| Incremental costs = −544.00 | ||||||||

| Adverse events cost (per patient) | GBP | Daptomycin = 34.00 | ||||||

| Vancomycin = 6.00 | ||||||||

| Incremental costs = 28.00 | ||||||||

| Total cost (per patient) | GBP | Daptomycin = 17,917.00 | ||||||

| Vancomycin = 17,165.00 | ||||||||

| Incremental costs = 752.00 | ||||||||

| Zhen et al. 2021 [88] (2013–2015) | No data | Seven pathogens d | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Total hospital cost—Susceptible (mean) | USD | 9558.00 | |

| Total hospital cost—Single-drug resistance (SDR) (mean) | 10,702.00 | |||||||

| Total hospital cost—Mean difference (Susceptible vs. SDR) | 1144.00 | |||||||

| Total hospital cost—multidrug resistance (MDR) | 13,017.00 | |||||||

| Total hospital cost—Mean difference (Susceptible vs. MDR) | 3391.00 | |||||||

| Length of hospital stay—Susceptible (mean) | Days | 22.01 | ||||||

| Length of hospital stay—Single-drug resistance (SDR) (mean) | 26.07 | |||||||

| Length of hospital stay—Mean difference (Susceptible vs. SDR) | 4.09 | |||||||

| Length of hospital stay—multidrug resistance (MDR) | 27.7 | |||||||

| Length of hospital stay—Mean difference (Susceptible vs. MDR) | 5.48 | |||||||

| In-hospital mortality rates—Susceptible (mean) | Percentage | 1.92 | ||||||

| In-hospital mortality rates—Single-drug resistance (SDR) (mean) | 2.67 | |||||||

| In-hospital mortality rates—Mean difference (Susceptible vs. SDR) | 0.78 | |||||||

| In-hospital mortality rates—multidrug resistance (MDR) | 3.58 | |||||||

| In-hospital mortality rates—Mean difference (Susceptible vs. MDR) | 1.50 | |||||||

| Liu et al. 2022 [82] (2017–2018) | Healthcare-associated infections | No data | No data | Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | The additional total medical expenses (for HAIs) | USD | 164.63 | |

| Medical expenses (for HAIs) | 114.96 | |||||||

| Out-of-pocket expenses (for HAIs) | 150.79 | |||||||

| Hospitalization days (for HAIs) | Days | 7 | ||||||

| The additional total medical expenses (for HAIs AMR) | USD | 381.15 | ||||||

| Medical expenses (for HAIs AMR)) | 202.37 | |||||||

| Out-of-pocket expenses (for HAIs AMR | 370.56 | |||||||

| Hospitalization days (for HAIs AMR) | Days | 9 | ||||||

| Labreche et al. 2013 [79] (2011) | Skin and soft tissue infections | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| Human/Community-based | Estimated Additional Costs of Treatment Failure—Hospital admission | USD | 1. 17,591.07 | |

| Estimated Additional Costs of Treatment Failure—Outpatient incision and drainage | 2. 2130.96 | |||||||

| Estimated Additional Costs of Treatment Failure—Emergency department visit | 3. 754.84 | |||||||

| Estimated Additional Costs of Treatment Failure—Mean additional cost (per patient) | 4. 1933.71 | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Bacitracin ointment | 5.23/tube | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Mupirocin ointment | 0.31/25 g | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Cephalexin 500 mg capsules | 0.11/capsule | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablets | 0.15/tablet | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Clindamycin 300 mg capsules | 0.20/capsule | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Clindamycin 150 mg capsules | 0.07/capsule | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Doxycycline 100 mg capsules | 0.04/capsule | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole double-strength tablets | 0.04/tablet | |||||||

| Unit cost of antibiotics—Clindamycin 600 mg intravenous solution | 2.24/600 mg | |||||||

| Kim et al. 2001 [6] (1996–1998) | No data | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | No data | Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | Additional hospital days attributable to MRSA infection (mean) | Days | 14 | |

| Total attributable cost to treat MRSA infections | Canadian Dollar (CAD) | 287,200.00 | ||||||

| Per patient-attributable cost to treat MRSA infections | 14,360.00 | |||||||

| The total cost for isolation and management of colonized patients | 128,095.00 | |||||||

| Per admission cost for isolation and management of colonized patients | 1363.00 | |||||||

| Costs for MRSA screening in the hospital | 109,813.00 | |||||||

| Costs associated with MRSA in Canadian hospitals (Range) | 42,000,000.00–59,000,000.00 | |||||||

| Uematsu et al. 2016 [66] (2013) | Pneumonia | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | No data | Human/Hospitals and Community based | Median (IQR) length of stay (MRSA group and Control) | Days | 21 (14–33) and 14 (9–23) | |

| Median (IQR) antibiotic cost (MRSA group and Control) | USD | 757.00 (436.00–1482.00) and 152.00 (77.00–347.00) | ||||||

| Median hospitalization cost (MRSA group and Control) | 8751.00 (6007.00–14,598.00) and 4474.00 (3214.00–6703.00) | |||||||

| Length of stay (Propensity score-matched group) | Days | 9 (1.6) | ||||||

| Antibiotic cost (Propensity score-matched group) | USD | 1044.00 (101.00) | ||||||

| Hospitalization cost (Propensity score-matched group) | 5548.00 (580.00) | |||||||

| Vasudevan et al. 2015 [78] (2007–2011) | Systemic inflammatory response syndrome | Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli | No data | Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | Median total hospitalization costs (range) for patients with RGNB | Singapore Dollars | 2637.80 (458.70–20,610.30) | |

| Median total hospitalization costs (range) for patients with no GNB | 2795.90 (506.90–4882.30) | |||||||

| Esther et al. 2012 [84] (2007–2009) | Multidrug resistance in Gram-negative infections |

| No data | Human/Hospital-based | Total hospitalization cost (IQR) | Singapore Dollars | 22,651.24 (11,046.84–48,782.93) | |

| Excess l hospitalization cost | 8638.58 | |||||||

| Roberts et al. 2009 [73] (2000) | Antimicrobial-resistant infection | No data | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Medical costs attributable to ARI (Range) | USD | 18,588.00–29,069.00 | |

| Excess duration of hospital stays (Range) | Days | 6.4–12.7 | ||||||

| Societal costs (Range) | USD | 10,700,000.00–15,000,000.00 | ||||||

| Total cost | USD | 13,350,000.00 | ||||||

| Nahuis et al. 2012 [126] (1998–2001) | No data | Clomiphene citrate-resistant polycystic ovary syndrome |

| Human/Hospital-based | Mean costs per first live birth—for the electrocautery group | Euro | 11,176.00 (95% CI: 9689.00–12,549.00) | |

| Mean costs per first live birth—for the recombinant FSH group | 14,423.00 (95% CI: 12,239.00–16,606.00) | |||||||

| Mean difference—Electrocautery vs. Recombinant FSH group | 3247.00 (95% CI: 650.00–5814.00) | |||||||

| Wozniak et al. 2019 [7] (2014) |

|

|

| Human/Hospital-based | Total cost (95% Uncertainty interval) | Australian dollar | Ceftriaxone-resistant E. coli BSI: 5839,782.00 (2,288,318.00–11,176,790.00) | |

| Ceftriaxone-resistant KP BSI: 1,351,360.00 (358,717.00–3,158,370.00) | ||||||||

| Ceftazidime-resistant PA BSI: 108,581.00 (48,551.00–202,756.00) | ||||||||

| Ceftazidime-resistant PA RTI: 1,296,324.00 (456,198.00–2,577,397.00) | ||||||||

| VRE BSI: 1404,064.00 (415,766.00–3,287,542.00) | ||||||||

| MRSA BSI: 5,546,854.00 (339,633.00 –22,688,754.00) | ||||||||

| MRSA RTI: 1,525,552.00 (726,903.00–2,791,453.00) | ||||||||

| Young et al. 2007 [127] (2004–2005) | Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection | Acinetobacter baumannii | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Attributable excess patient charge due to Acinetobacter baumannii | USD | 60,913.00 | |

| Excess hospital days due to Acinetobacter baumannii | Days | 13 | ||||||

| Mean hospital charge (Case vs. Control) | USD | 306,877.00 vs. 135,986.00 | ||||||

| Mean duration of hospitalization (Case vs. Control) | Days | 25.4 vs. 7.6 | ||||||

| Madan et al. 2020 [69] (2012–2018) | Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis | No data | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Healthcare costs per participant (South Africa—Long-term treatment) | USD | 8340.70 | |

| Healthcare costs per participant (South Africa—short-term treatment) | 6618.00 | |||||||

| Healthcare costs per participant (South Africa—short-term treatment) | 6096.60 | |||||||

| Healthcare costs per participant (Ethiopia—Long-term treatment) | 4552.30 | |||||||

| Medication cost savings—South Africa | Percentage (USD) | 67.0 (1157.00 of total 1722.80) | ||||||

| Medication cost savings—Ethiopia | 35.0 (545.20 of 1544.30) | |||||||

| Zhen et al. 2018 [71] (2014–2015) | Multiple drug-resistant intra-abdominal infections | No data | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Total medical cost (TMC)—among patients with MDR pathogens | Chinese Yuan | 131,801.00 | |

| Total medical cost—among patients without MDR pathogen | 90,201.00 | |||||||

| Sum of all attributable total medical costs (for whole country) | 37,000,000,000.00 | |||||||

| The societal costs | 111,000,000,000.00 | |||||||

| The mean TMC difference between the MDR and non-MDR groups | 90,201.00 | |||||||

| Desai et al. 2021 [75] (2019) | Treatment-resistant depression | No data | Esketamine nasal spray + oral antidepressant (ESK + oral AD) vs. Oral AD plus nasal placebo (oral AD + PBO) | Human/Setting—no data | Commercial | USD | 85,808.00 vs. 100,198.00 | |

| Medicaid | 76,236.00 vs. 96,067.00 | |||||||

| Veteran’s Affairs | 77,765.00 vs. 104,519.00 | |||||||

| Integrated Delivery Network | 103,924.00 vs. 142,766.00 | |||||||

| Szukis et al., 2021 [85] (2014–2018) | Major depressive disorders—MDD (psychosis, schizophrenia, manic/bipolar disorder, or dementia) with and without treatment-resistant depression | No data | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Incidence rate ratio—IRR in non-TRD MDD | Ratio | 1.7 [95% CI 1.57–1.83] | |

| Incidence rate ratio (IRR)—Non-MDD | 5.04 [95% CI 4.51–5.63] | |||||||

| Mean difference in total healthcare cost (TRD and non-TRD MDD) | USD | 5906.00 | ||||||

| Mean difference in total healthcare cost (TRD and non-MDD) | 11,873.00 | |||||||

| Stewardson et al., 2016 [74] (2016) | Bloodstream infections |

| No data | Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | Length of stay—3GCRE | Days (95% Confidence Interval) | 9.3 (9.2–9.4) | |

| Length of stay—MSSA | 11.5 (11.5–11.6) | |||||||

| Length of stay—MRSA | 13.3 (13.2–13.4) | |||||||

| Cost from hospital perspective—lowest per infection cost (for 3GCSE): Using economic valuations | Euro (95% Credible Interval) | 320.00 (80.00–1300.000 | ||||||

| Cost from hospital perspective—lowest per infection cost (for 3GCSE): Using accounting valuations | 4000.00 (2400.00–6700.00) | |||||||

| Cost from hospital perspective—highest annual cost (With MSSA): Using economic valuation | Euro (95% credible interval) | 77,000.00 (19,000.00–300,000.00) | ||||||

| Cost from hospital perspective—highest annual cost (With MSSA): Using accounting valuations | 970,000.00 (590,000.00–1,600,000.00) | |||||||

| Lester et al., 2023 [128] (2023) | Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant bloodstream infection |

| No data | Human/Hospital-based | Mean health provider cost per participant | USD (95% CR) | 110.27 (22.60–197.95) | |

| Additional indirect cost (Patients with resistant BSI) | USD (95% CR) | 155.48 (67.80–378.78) | ||||||

| Additional direct nonmedical costs (Patients with resistant BSI) | USD (95% CR) | 20.98 (36.47–78.42) | ||||||

| Lu et al., 2021 [129] (2021) | Pneumococcal disease | No data | Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) vs. Antibiotics (penicillin, amoxicillin, third-generation cephalosporins, and meropenem) | Human/Hospital-based | Reduction in AMR due to PCV against penicillin, amoxicillin, and third-generation cephalosporins (99% coverage in 5 years) | Percentage | 6.6, 10.9 and 9.8 | |

| Reduction in AMR due to PCV against penicillin, amoxicillin, and third-generation cephalosporins (coverage increased to 85% over 2 years, and followed by 3 years to reach 99%) | 10.5, 17.0, 15.4 | |||||||

| Reduction in cumulative costs of AMR (including direct and indirect costs of patients and caretakers) (coverage increased to 99% coverage in 5 years) | USD | 371 million | ||||||

| Reduction in cumulative costs of AMR (including direct and indirect costs of patients and caretakers) (Coverage increased to 85% over 2 years) | 586 million | |||||||

| Janis et al., 2014 [83] (2014) | Hand infection | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Vancomycin or Cefazolin | Human/Hospital-based | Mean length of stay—Patients randomized to cefazolin | Days | 5.75 | |

| Mean length of stay—Patients randomized to vancomycin | 4.23 | |||||||

| Cost of treatment—Patients randomized to cefazolin | USD | 6693.23 | ||||||

| Cost of treatment—Patients randomized to vancomycin | 4589.41 | |||||||

| Mahmoudi et al., 2020 [80] (2020) | No data | No data | Pre and post Antimicrobial Stewardship Program | Human/Hospital-based | Total defined daily dose per 1000 patient days: Pre-ASP | Number of doses | 129.1 | |

| Total defined daily dose per 1000 patient days—post-ASP | Number of doses | 95.2 | ||||||

| Total defined daily dose per 1000 patient days—Difference | Percentage | −26.3 | ||||||

| Total monthly cost of antimicrobial administration—Pre-ASP | USD | 437,572.00 | ||||||

| Total monthly cost of antimicrobial administration—post-ASP | USD | 254,520.00 | ||||||

| Total monthly cost of antimicrobial administration—Difference | Percentage (p value) | −41.8 (< 0.001) | ||||||

| Imai et al., 2022 [130] (2022) | Carbapenem-resistant (CR) bacterial infection—pneumonia, urinary tract infection, biliary infection, and sepsis/Carbapenem-susceptible (CS) infections | No data | Carbapenem | Human/Hospital-based | Cost of CR vs. CS infections—Medications | USD—Median | 3477.00 vs. 1609.00 | |

| Cost of CR vs. CS infections—Laboratory tests | 2498.00 vs. 1845.00 | |||||||

| Cost of CR vs. CS infections—Hospital stays | 14,307.00 vs. 10,560.00 | |||||||

| Disease burden | Cassini et al. 2019 [94] (2015) |

| Seven pathogens e | No data | Human/Community-based | Disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) | Lost years of full health (Uncertainty intervals) | 874,541 (768,837–989,068) |

| Attributable deaths | Number of deaths (Uncertainty intervals) | 33,110 (28,480–38,430) | ||||||

| Attributable deaths per 100,000 population | Number of deaths (Uncertainty intervals) | 6.44 (5.54–7.48) | ||||||

| DALYs per 100,000 population | Lost years of full health (Uncertainty intervals) | 170 (150–192) | ||||||

| Kritsotakis et al. 2017 [90] (2012) |

| Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative pathogen | No data | Human/Hospital-based | 1. HAI prevalence | 1. Percentage (95% CI) | 1. 9.1 (7.8–10.6) | |

| 2. Estimated annual HAI incidence | 2. Percentage (95% CI) | 2. 5.2 (4.4–5.3) | ||||||

| 3. Length of stay (LOS) | 3. Days (95% CI) | 3. 4.3 (2.4–6.2) | ||||||

| 4. Mean excess LOS | 4. Days | 4. 20 | ||||||

| Le and Miller. 2001 [93] (2000) | Uncomplicated urinary tract infections | Escherichia coli (EC) |

| Human/Hospital-based | The mean cost of TMP-SMZ: When the proportion of resistant EC was 0% | USD | 92.00 | |

| The mean cost of TMP-SMZ: When the proportion of resistant EC was 20% | 106.00 | |||||||

| The mean cost of TMP-SMZ: When the proportion of resistant EC was 40% | 120.00 | |||||||

| Mean cost of empirical FQ treatment | 107.00 | |||||||

| Tsuzuki et al., 2021 [91] (2021) | Bloodstream infections | Nine pathogens f | No data | Human/Hospital-based | DALYs (Per 100,000 population) | Years | 137.9 [95% uncertainty interval (UI) 130.7–145.2] | |

| DALYs [Median (IQR)] per 100,000 population | 145.7 (108.4–172.4) | |||||||

| Wozniak et al., 2022 [92] (2022) |

|

| No data | Human/Hospital-based | Cost of premature death | Australian Dollar | 438,543,052.00 | |

| Total hospital cost | Australian Dollar | 71,988,858.00 | ||||||

| Loss of quality-adjusted life years | Years | 27,705 | ||||||

| CBA | Puzniak et al. 2004 [95] (1997–1999) | No data | Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Attributable annual cost/Incremental cost of gown policy | USD | 73,995.00 |

| Averted cases | No of cases | 58 | ||||||

| Total averted VRE attributable medical intensive care unit cost | USD | 493,341.00 | ||||||

| Simoens et al. 2009 [96] (2007) | No data | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | No data | Human/Hospital-based | Benefits of search and destroy policy (intensive care unit) | Euro | 16,058.00 | |

| Benefits of search and destroy policy (Gerontology unit) | Euro | 9321.00 | ||||||

| Benefit-cost ratio of search and destroy policy (intensive care unit) | Ratio | 1.17 | ||||||

| Benefit-cost ratio of search and destroy policy (Gerontology unit) | Ratio | 1.16 | ||||||

| CUA | Varon-Vega et al. 2022 [97] (2019) | No data | Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae | Ceftazidime-Avibactam (CAZ-AVI) vs. Colistin-meropenem (COL + MEM) | Human/Hospital-based | Increase in QALYs per patient (CAZ-AVI vs. COL + MEM) | Years | 1.76 |

| Incremental costs (CAZ-AVI vs. COL + MEM) | USD | 2521.00 | ||||||

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio | USD | 3317.00 | ||||||

| Chen et al. 2019 [98] (2018) | Complicated urinary tract infection | Gram-negative Bacteria (GNB) |

| Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | Total medical cost | USD | 4199.01 vs. 3594.76 | |

| QALYs | Years | 4.8 vs. 4.78 | ||||||

| Additional cost per discounted QALY gained | USD | 32,521.08 | ||||||

| CMA | Farquhar et al. 2004 [99] (1996–1999) | Infertility | Clomiphene citrate-resistant polycystic ovary syndrome | Laparoscopic ovarian diathermy (Treatment I) vs. Gonadotrophins (Treatment II) | Human/Hospital-based (tertiary) | Chance of pregnancy | Percentage | Treatment I and II: 27.0 and 33.3 |

| Chance of live birth | Percentage | Treatment I and II: 14.0 and 19.0 | ||||||

| Cost per patient | New Zealand dollar (NZD) | Treatment I and II: 2953.00 and 5461.00 | ||||||

| Cost per pregnancy | NZD | Treatment I and II: 10,938.00 and 16,549.00 | ||||||

| Cost per live birth | NZD | Treatment I and II: 21,095.00 and 28,744.00 |

References

- World Health Organization. An Update on the Fight Against Antimicrobial Resistance. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/an-update-on-the-fight-against-antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Sathyapalan, D.T.; James, J.; Sudhir, S.; Nampoothiri, V.; Bhaskaran, P.N.; Shashindran, N.; Thomas, J.; Prasanna, P.; Mohamed, Z.U.; Edathadathil, F.; et al. Antimicrobial Stewardship and Its Impact on the Changing Epidemiology of Polymyxin Use in a South Indian Healthcare Setting. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. New Report Calls for Urgent Action to Avert Antimicrobial Resistance Crisis. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-04-2019-new-report-calls-for-urgent-action-to-avert-antimicrobial-resistance-crisis (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- World Bank. Drug-Resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future. n.d. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/publication/drug-resistant-infections-a-threat-to-our-economic-future (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Kim, T.; Oh, P.I.; Simor, A.E. The Economic Impact of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canadian Hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2001, 22, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, T.M.; Bailey, E.J.; Graves, N. Health and economic burden of antimicrobial-resistant infections in Australian hospitals: A population-based model. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulingam, T.; Parumasivam, T.; Gazzali, A.M.; Sulaiman, A.M.; Chee, J.Y.; Lakshmanan, M.; Chin, C.F.; Sudesh, K. Antimicrobial resistance: Prevalence, economic burden, mechanisms of resistance and strategies to overcome. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 170, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, S.; Shrestha, P.; Adhikari, B. Antimicrobial use in food animals and human health: Time to implement ‘One Health’ approach. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infctions Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. 2016. Available online: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Coast, J.; Smith, R.D. Antimicrobial resistance: Cost and containment. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2003, 1, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, H.M.; McEwan, P.J. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Methods and Applications, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 4, 308p. [Google Scholar]

- Mishan, E.J.; Quah, E. Cost-Benefit Analysis, 6th ed.; Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; 404p. [Google Scholar]

- Dernovsek, M.Z.; Rupel, V.P.; Tavcar, R. Cost-Utility Analysis. In Quality of Life Impairment in Schizophrenia, Mood and Anxiety Disorders-New Perspectives on Research and Treatment; Ritsner, M.S., Awad, A.G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 373–384. [Google Scholar]

- Duenas, A. Cost-Minimization Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, T.A. Costs of illness in cost-effectiveness analysis. A review of the methodology. Pharmacoeconomics 1994, 6, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byford, S.; Torgerson, D.J.; Raftery, J. Economic note: Cost of illness studies. BMJ 2000, 320, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J.S. Global Health and the Global Burden of Disease. In An Introduction to Global Health Delivery; Mukherjee, J.S., Ed.; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hessel, F. Burden of Disease. In Encyclopedia of Public Health; Kirch, W., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 111, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, J.P.; Kumar, R.; Carmeli, Y. Accounting for the Development of Antibacterial Resistance in the Cost Effectiveness of Ertapenem versus Piperacillin/Tazobactam in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections in the UK. Pharmacoeconomics 2009, 27, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Wassenberg, M.W.; De Wit, G.A.; Van Hout, B.A.; Bonten, M.J.M. Quantifying cost-effectiveness of controlling nosocomial spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria: The case of MRSA. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, M.C.; Goldie, S.J.; Losina, E.; Cohen, C.J.; Baxter, J.D.; Zhang, H.; Kimmel, A.D.; Freedberg, K.A. Use of Genotypic Resistance Testing To Guide HIV Therapy: Clinical Impact and Cost-Effectiveness. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 134, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cock, E.; Krueger, W.A.; Sorensen, S.; Baker, T.; Hardewig, J.; Duttagupta, S.; Müller, E.; Piecyk, A.; Reisinger, E.; Resch, A. Cost-effectiveness of linezolid vs vancomycin in suspected methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia in Germany. Infection 2009, 37, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.; Edlund, C.; Nauclér, P.; Svensson, M.; Ternhag, A. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Temocillin Treatment in Patients with Febrile UTI Accounting for the Emergence of Antibiotic Resistance. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2022, 20, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiridou, M.; Lugnér, A.; de Vries, H.J.; van Bergen, J.E.; Götz, H.M.; van Benthem, B.H.; Wallinga, J.; van der Sande, M.A. Cost-Effectiveness of Dual Antimicrobial Therapy for Gonococcal Infections Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in the Netherlands. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2016, 43, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Haider, S.; Liu, S.; Gao, X. Economic evaluation among Chinese patients with nosocomial pneumonia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and treated with linezolid or vancomycin: A secondary, post-hoc analysis based on a Phase 4 clinical trial study. J. Med. Econ. 2016, 19, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwin, E.; Varughese, M.; Waldner, D.; Simmonds, K.; Joffe, A.M.; Smith, S. Comparing methods to estimate incremental inpatient costs and length of stay due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Alberta, Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederman, M.S.; Chastre, J.; Solem, C.T.; Wan, Y.; Gao, X.; Myers, D.E.; Haider, S.; Li, J.Z.; Stephens, J.M. Health economic evaluation of patients treated for nosocomial pneumonia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of vancomycin and linezolid. Clin. Ther. 2014, 36, 1233–1243.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.P.; Kumar, R.; Carmeli, Y. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of ertapenem versus piperacillin/tazobactam in the treatment of complicated intraabdominal infections accounting for antibiotic resistance. Value Health 2009, 12, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Darlington, O.; Miller, R.; Gordon, J.; McEwan, P.; Ohashi, T.; Taie, A.; Yuasa, A. Estimating the Economic and Clinical Value of Reducing Antimicrobial Resistance to Three Gram-negative Pathogens in Japan. J. Health Econ. Outcomes Res. 2021, 8, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong, R.; Smith, R.D.; Little, P.; Verheij, T.; Butler, C.C.; Goossens, H.; Coenen, S.; Moore, M.; Coast, J. Cost effectiveness of amoxicillin for lower respiratory tract infections in primary care: An economic evaluation accounting for the cost of antimicrobial resistance. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e633-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysham, W.Z.; Schaffer, E.M.; Coles, T.; Roque, D.R.; Wheeler, S.B.; Kim, K.H. Adding bevacizumab to single agent chemotherapy for the treatment of platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: A cost effectiveness analysis of the AURELIA trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tringale, K.R.; Carroll, K.T.; Zakeri, K.; Sacco, A.G.; Barnachea, L.; Murphy, J.D. Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Nivolumab for Treatment of Platinum-Resistant Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Yang, X.; Shu, Y.; Li, S.; Song, B.; Yang, K. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ceftazidime-avibactam as definitive treatment for treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1118307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel Mullins, C.; Kuznik, A.; Shaya, F.T.; Obeidat, N.A.; Levine, A.R.; Liu, L.Z.; Wong, W. Cost-effectiveness analysis of linezolid compared with vancomycin for the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Ther. 2006, 28, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawsitt, C.G.; Vickerman, P.; Cooke, G.S.; Welton, N.J.; Barnes, E.; Ball, J.; Brainard, D.; Burgess, G.; Dillon, J.; Foster, G.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Baseline Testing for Resistance-Associated Polymorphisms to Optimize Treatment Outcome in Genotype 1 Noncirrhotic Treatment-Naive Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus. Value Health 2020, 23, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Quilici, S.; File, T.; Garau, J.; Kureishi, A.; Kubin, M. Cost-effectiveness of empirical prescribing of antimicrobials in community-acquired pneumonia in three countries in the presence of resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 59, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinghurst, S.; Carroll, F.E.; Abel, A.; Campbell, J.; Garland, A.; Jerrom, B.; Kessler, D.; Kuyken, W.; Morrison, J.; Ridgway, N.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in primary care: Economic evaluation of the CoBalT Trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 204, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, E.L.; Soeteman, D.I. Cost-Effectiveness of Esketamine Nasal Spray for Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.M.; Yang, T.-T.; Chao, S.-H.; Li, Y.-X.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Zhang, H.-H.; Lan, L.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Wang, X.-M.; Zhang, Y.-R.; et al. Comparison the cost-efficacy of furazolidone-based versus clarithromycin-based quadruple therapy in initial treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in a variable clarithromycin drug-resistant region, a single-center, prospective, randomized, open-label study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14408. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.; Moore, L.; Quilici, S.; Decramer, M.; Simoens, S. A cost-effectiveness analysis of antimicrobial treatment of community-acquired pneumonia taking into account resistance in Belgium. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2008, 24, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding-Esch, E.M.; Huntington, S.; Harvey, M.J.; Weston, G.; Broad, C.E.; Adams, E.J.; Sadiq, S.T. Antimicrobial resistance point-of-care testing for gonorrhoea treatment regimens: Cost-effectiveness and impact on ceftriaxone use of five hypothetical strategies compared with standard care in England sexual health clinics. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 1900402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sado, M.; Koreki, A.; Ninomiya, A.; Kurata, C.; Mitsuda, D.; Sato, Y.; Kikuchi, T.; Fujisawa, D.; Ono, Y.; Mimura, M.; et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses of augmented cognitive behavioral therapy for pharmacotherapy-resistant depression at secondary mental health care settings. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 75, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, S.; Wu, D.B.-C.; You, R. Cost-Effectiveness of Testing for NS5A Resistance to Optimize Treatment of Elbasvir/Grazoprevir for Chronic Hepatitis C in China. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 717504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseille, E.; Kahn, J.G.; Yazar-Klosinski, B.; Doblin, R. The cost-effectiveness of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of chronic, treatment-resistant PTSD. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac, S.; Fitzpatrick, T.; Johnstone, J.; Sander, B. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) screening and isolation in the general medicine ward: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.L.; Lefrak, S.N.; Lyman, J.; Smith, R.L.; Chong, T.W.; McElearney, S.T.; Schulman, A.R.; Hughes, M.G.; Raymond, D.P.; Pruett, T.L.; et al. Cost of Gram-negative resistance. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, J.P.; Al Taie, A.; Miller, R.L.; Dennis, J.W.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Iredell, J.R.; Turnidge, J.D.; Coombs, G.W.; Grolman, D.C.; Youssef, J. Quantifying the Economic and Clinical Value of Reducing Antimicrobial Resistance in Gram-negative Pathogens Causing Hospital-Acquired Infections in Australia. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosu, L.; Madan, J.J.; Tomeny, E.M.; Muniyandi, M.; Nidoi, J.; Girma, M.; Vilc, V.; Bindroo, P.; Dhandhukiya, R.; Bayissa, A.K.; et al. Economic evaluation of shortened, bedaquiline-containing treatment regimens for rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (STREAM stage 2): A within-trial analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e265–e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Jiang, Q.; Hu, H.; Han, J.; She, L.; Yao, L.; Ding, D.; Huang, J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of utidelone plus capecitabine for metastatic breast cancer in China. J. Med. Econ. 2019, 22, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.D.; Li, Y.; Anstrom, K.J.; Schulman, K.A. Cost effectiveness of ixabepilone plus capecitabine for metastatic breast cancer progressing after anthracycline and taxane treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 2185–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.T.; Antillon, M.; Bilcke, J.; Bar-Zeev, N.; Limani, F.; Debellut, F.; Pecenka, C.; Neuzil, K.M.; Gordon, M.A.; Thindwa, D.; et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of typhoid conjugate vaccines in an outbreak setting: A modeling study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, M.M.; Clemons, M.; Stober, C.; Jeong, A.; Vandermeer, L.; Mates, M.; Blanchette, P.; Joy, A.A.; Aseyev, O.; Pond, G.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of 12-Versus 4-Weekly Administration of Bone-Targeted Agents in Patients with Bone Metastases from Breast and Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1847–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]