The Introduction of the Global Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Healthcare (TCIH) Research Agenda on Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Added Value to the WHO and the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH 2023 Research Agendas on Antimicrobial Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Burden of AMR

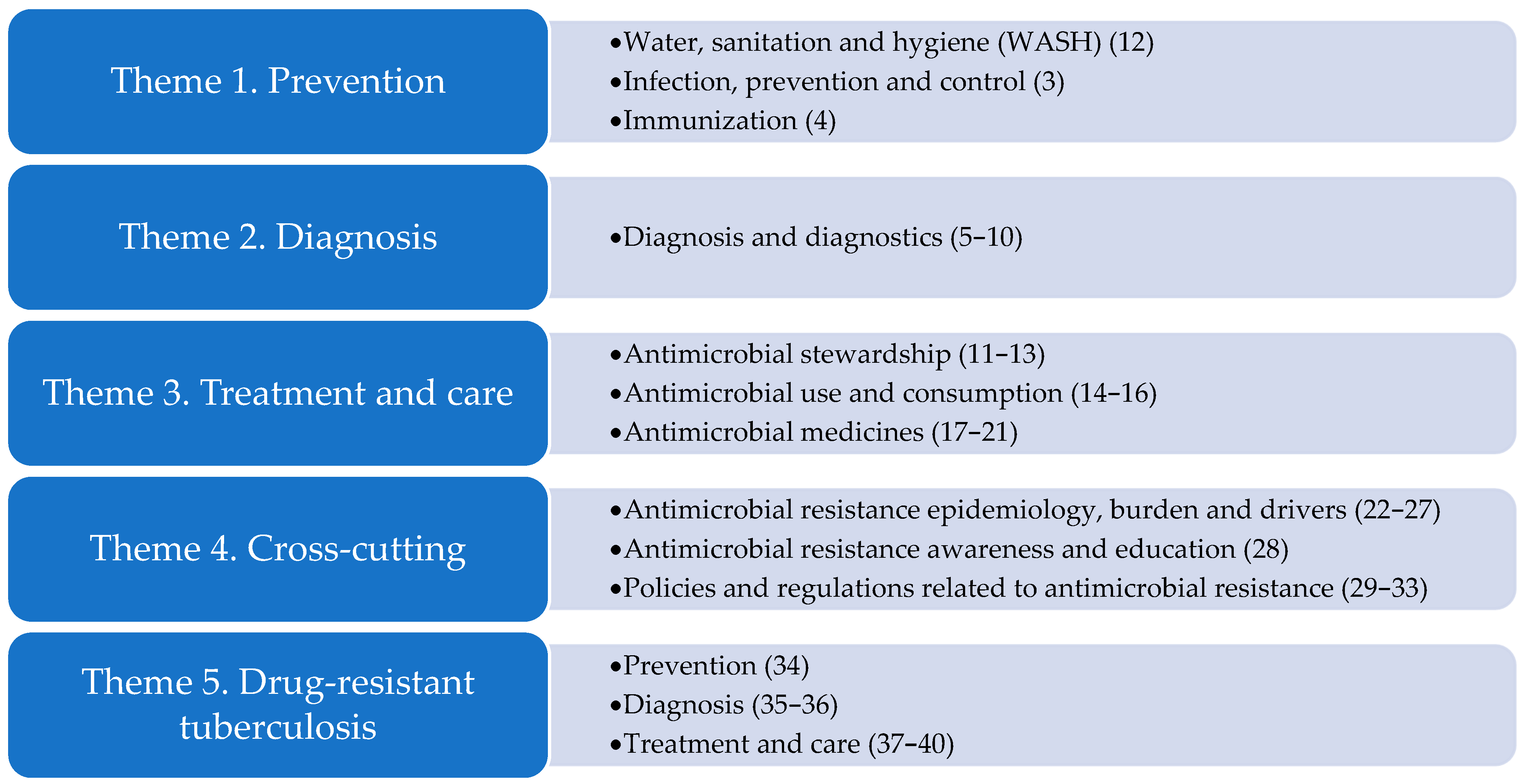

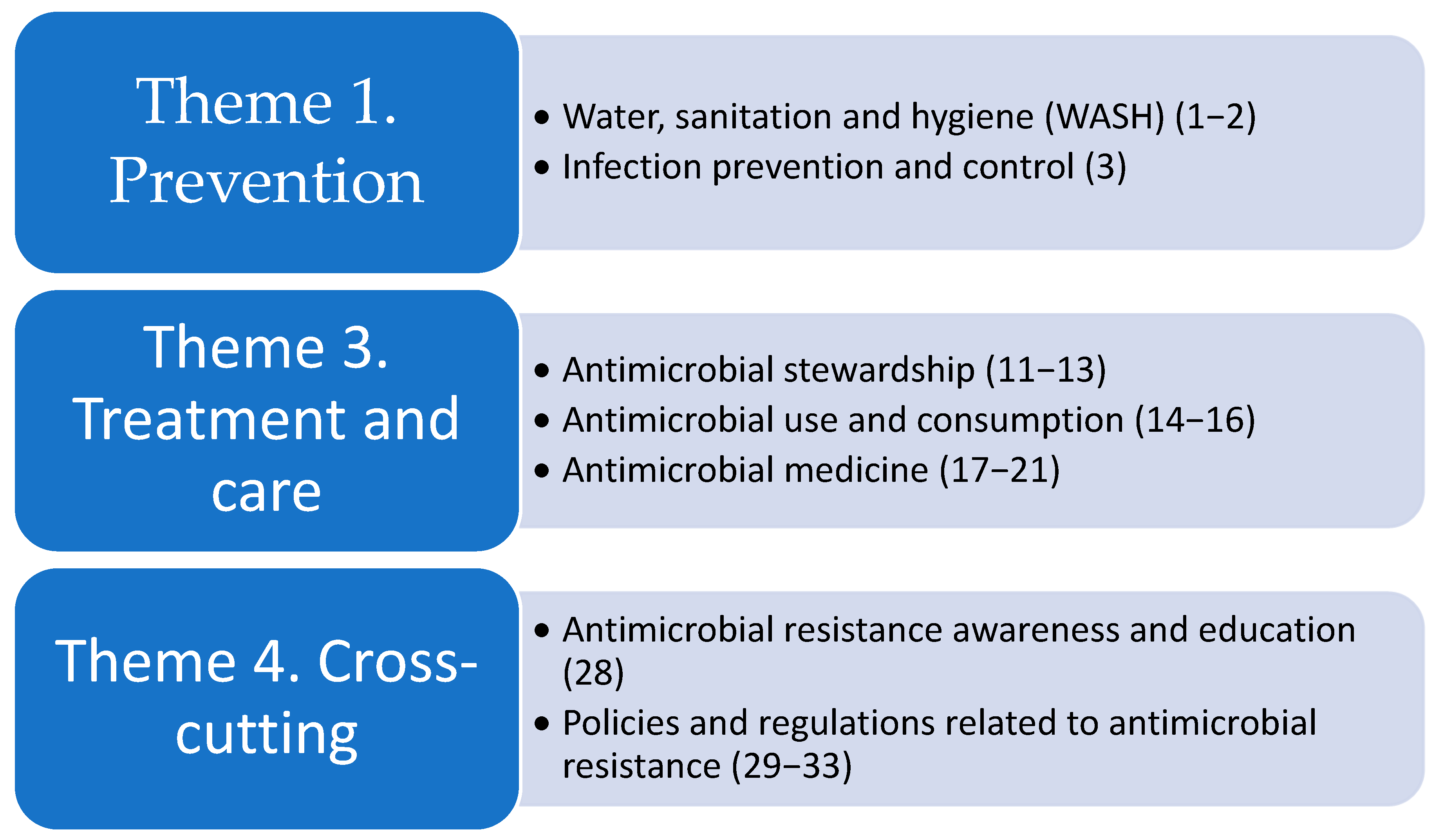

1.2. Global Research Agendas on AMR

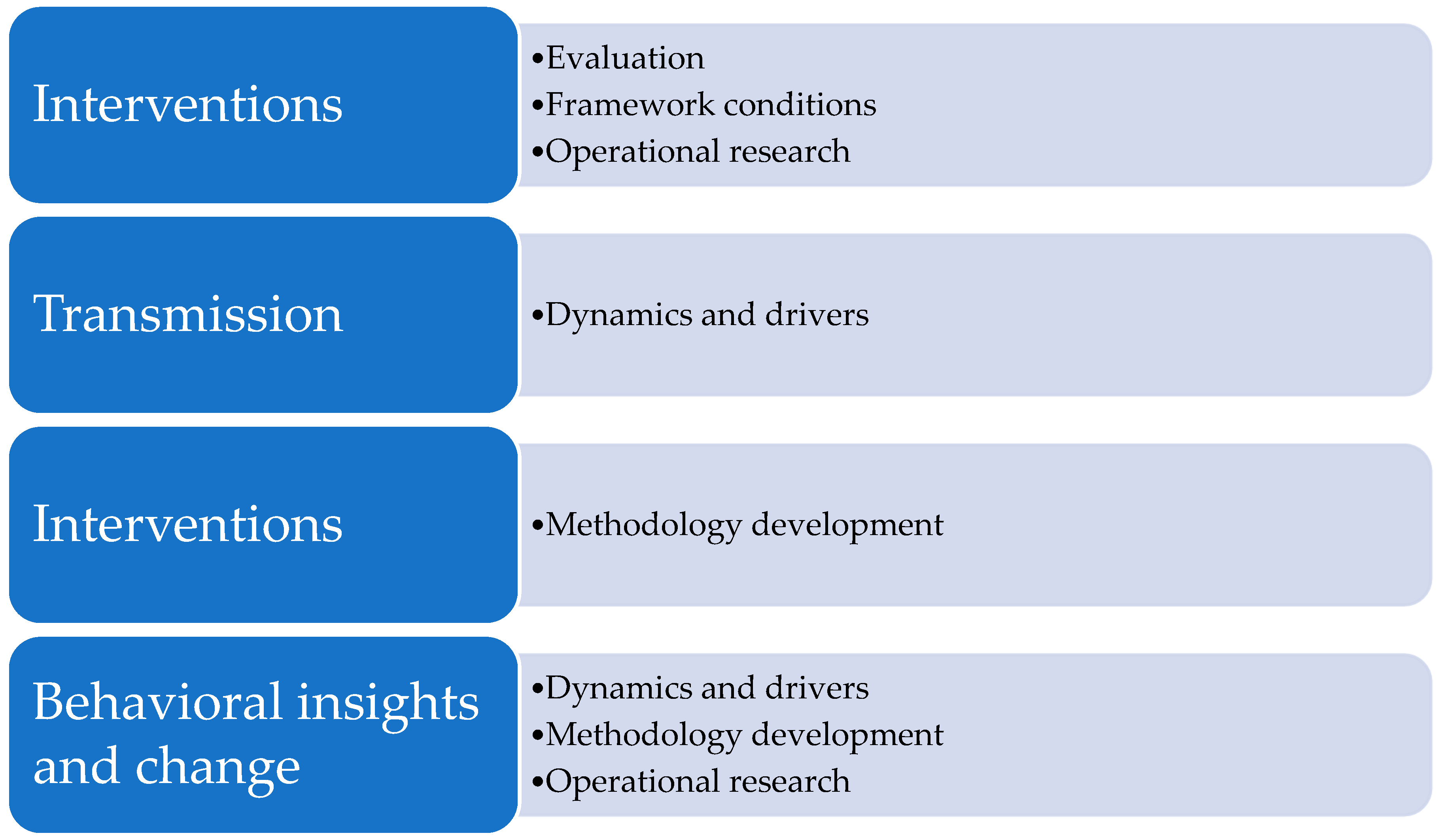

- Transmission: This pillar focuses on where the transmission, circulation, and spread of AMR occur among the environment, plants, animals, and humans, what drives this transmission, where it happens, and its impact. This focus includes transmission dynamics, risk assessment, and modeling, and how practices enacted by humans at the interface between humans, plants, animals, and the wider environment (soil, water, and air) enable the development and spread of resistance.

- Integrated surveillance: This pillar aims to identify priority research questions focusing on cross-sector surveillance that improves common technical understanding and exchange of information. Included are questions about harmonization, effectiveness, implementation of One Health integrated surveillance and applicability to LMICs; it may include considerations for innovative surveillance approaches to AMR.

- Interventions: This pillar covers programs, practices, tools, and activities designed to prevent, contain, or reduce the incidence, prevalence, and dissemination of AMR, including optimal use of existing vaccines and other measures across the One Health spectrum.

- Behavioral insights and change: This pillar focuses on behavioral drivers of AMR by understanding influences on human behavior in different contexts (social influences and support, livelihoods, financial resources, etc.). This pillar operates at multiple levels of complex systems, including organizational structures that enable or disable AMR mitigation, as well as individual and interpersonal sociocultural practices.

- Economics and policy: This pillar addresses investment and action in AMR mitigation from a One Health perspective. Included are policy, governance, legislative and regulatory instruments, cross-sector processes and strategies affecting AMR (e.g., regulation of antimicrobial manufacturing, use, disposal, monitoring), joint planning, and policy goals among ministries. Cost-effectiveness considerations are also included to support the development of the AMR investment case. Finally, this pillar includes financial sustainability and long-term financial impact.

1.3. The Scientific Status of Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Healthcare (TCIH) for the Prevention and Treatment of Infections

1.4. Patients’, Animal Owners’, Farmers’ Preferences and Doctors’ (Non-) Prescription of TCIH Medicinal Products

1.5. The GIFTS-AMR Project

- To develop a global “Traditional Solutions to Antimicrobial Resistance” network by mapping and connecting the research fields, research institutes, and researchers in human and animal healthcare and infrastructures involved in research on TCIH.

- To develop research agendas starting with at least one to three prioritized indications both in human and veterinary healthcare.

- To prepare grant proposals for research projects and the continuation of the network after the JPIAMR-funded GIFTS-AMR project.

- To communicate to relevant stakeholders the existence, activities, and output (e.g., research agendas, website) of the network, both online (report on website and webinars) and during an (online) international conference [69].

1.6. Study Aim

- To present the research themes, priorities, and projects of the developed global TCIH research agenda on AMR

- To describe its added value to the WHO Global Research Agenda for Antimicrobial Resistance in Human Health 2023 and the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH One Health Priority Research Agenda for Antimicrobial Resistance 2023.

2. Results

2.1. The Global TCIH Research Agenda on AMR

- The value of TCIH medicinal products

- The best TCIH product–market combinations

- The most promising TCIH medicinal products for high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

- The use of limited evidence and real-world evidence of safety and effectiveness

- The transition towards full integration of TCIH in the medical systems

- Increasing the accessibility of TCIH medicinal products for infections (information)

2.2. The Additions to the WHO Research Agenda on AMR 2023

2.3. The Additions to the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH Research Agenda 2023

2.4. Newly Defined Research Themes and Research Priorities of the Global TCIH Research Agenda in Addition to the Two Existing Global AMR Research Agendas

- Patient preferences and stakeholders’ needs for non-antibiotic prevention and treatment strategies for infections

- o

- Assess patients’/animal owners’/farmers’ preferences, use, satisfaction, and acceptability of TCIH MPs in LMICs and developed countries.

- Use of limited evidence and real-world evidence:

- o

- Develop an adapted Evidence-to-Recommendation (EtR) system for TCIH MPs for infections using available evidence and additional arguments to weigh up the available information.

- o

- Investigate the feasibility of using identified additional arguments in an existing EtR framework.

- o

- Investigate the acceptability and need for improvements of these EtR procedures for all TCIH modalities in all countries.

- Safety, (cost-)effectiveness, benefits/risks ratios, and benefits/costs ratios of TCIH strategies in human and veterinary medicine

- o

- Investigate the feasibility and acceptability of integrating traditional and complementary approaches with conventional primary healthcare (for humans and animals) as a strategy to support the delayed use of antibiotics.

- o

- Investigate the types and working mechanisms of health promotion/resilience and antimicrobial effects of TCIH MPs.

- Implementation and information tools

- o

- Investigate the conceptual differences between conventional medicine and TCIH, which present a barrier to the acceptability and implementation of TCIH prevention and treatment of infections strategies.

3. Discussion

3.1. Strength and Limitations

3.2. Future Perspective

- Continue and broaden the international research network, building on the existing GIFTS-AMR network, consisting of TCIH and conventional researchers with different backgrounds and skills (veterinary/medical, human sciences, philosophical, historical, political, etc.) as well as professionals (doctors, veterinarians, pharmacists, biologists, physicists, chemists, pharmacologists, etc.) who are working towards a health-oriented healthcare system.

- Develop a formal, trustworthy global scientific ‘committee/working group’, recognized by conventional and TCIH stakeholders, which provides valid information on TCIH research, education, and information tools for the prevention and treatment of infections and reduction in AMR. This committee/working group should be responsible for the development of specific, high-quality databases on TCIH strategies and scientific evidence of TCIH research in this field to ensure patients, animal owners, farmers, healthcare professionals, and other stakeholders can access user-friendly evidence-based information/advice on TCIH.

- Develop and promote databases such as CAM on PubMed® and VHL by PAHO and CABSIN among professionals and academic researchers.

- Develop and use standards for evidence-based education of healthcare professionals (human and veterinary)—undergraduate and postgraduate.

- Consider a broad range of sources (e.g., context-based/real-world evidence, users’ preferences) in research and guideline development.

- Promote guideline development considering both quantitative and qualitative research, including results of ‘real-world evidence’ studies.

- Expand the role of ‘patient choice’ in future research, guideline development, and education (PPI, public and patient involvement) in those countries where this is not, or insufficiently, organized.

- Prioritize research on health/resilience promotion rather than disease control only.

- Develop information tools (eHealth, website) to provide easily accessible information on evidence.

- Promote One Health research and the collaboration between conventional medicine and TCIH in human, animal, and plant sectors at regional, national, and international levels in a timely manner while preserving the integrity of prescribing individualized TCIH treatments and while considering research on health/resilience promotion and disease-specific prevention rather than disease control only.

- Promote publicly funded research on TCIH treatments, their efficacy/(cost-)effectiveness and safety, and their underlying mechanisms or modes of action.

4. Methods

4.1. Research Questions

- What are the research themes, priorities, and prioritized projects of the global TCIH research agenda on AMR for the next 10 years?

- What does the global TCIH research agenda add to the forty research priorities, the thirteen AMR areas across five themes of the WHO AMR, and the five pillars of the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH research agendas 2023?

- Which newly defined research themes and priorities can be added to the two global AMR research agendas?

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Data Collection

4.2.2. A Comparison with the Two 2023 AMR Research Agendas

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| US$ | United States dollars |

Appendix A. Contributors to the TCIH Research Agenda

- E. Baars, Louis Bolk Institute/University of Applied Sciences Leiden, The Netherlands (coordinator)

- M. Emeje, National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Nigeria

- M. Fernandez, Portales IAVH, Spain

- M. Frass, Austrian Umbrella Organisation for Medical Holistic Therapy/WissHOM, Austria

- M. Guldas, Uludag University, Turkey

- Z. Girgin Ersoy, Uludag University, Turkey

- X. Hu, Univ. of Southampton, School of Primary Care, Population Sciences and Medical Education, UK

- R. Huber, University Medical Centre Freiburg, Germany

- M. Johnson, Organic Research Centre, UK

- E. Katuura, Makerere University, Uganda

- P. Little, Univ. of Southampton, School of Primary Care, Population Sciences and Medical Education, UK

- J. Liu, Centre for Evidence-Based Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, China

- D. Martin, University of Witten-Herdecke, Germany

- M. Moore, Univ. of Southampton, School of Primary Care, Population Sciences and Medical Education, UK

- T. Nicolai, Eurocam, Belgium

- E. Oppong Bekoe, University of Ghana, School of Pharmacy, Ghana

- P. Panhofer, Private Medical University, Sigmund Freud University, Austria

- BN. Prakash, The University of Trans-Disciplinary Health Sciences & Technology, India

- R. Sanogo, University of Sciences, Techniques and Bamako Technologies (USTTB), Faculty of Pharmacy, Mali

- K. Sørheim, Norwegian Centre for Organic Agriculture, Norway

- H. Szőke, University of Pécs, Hungary

- E. van der Werf, Homeopathy Research Institute (HRI), UK

- D. Vankova, Medical University of Varna, Bulgaria

- N. van Steenbergen, University of Applied Sciences Leiden, The Netherlands

- L. Veldman, University of Applied Sciences Leiden, The Netherlands

- H. van Wietmarschen, Louis Bolk Institute, The Netherlands

- P. Weiermayer, OEGVH/WissHom, Austria

- M. Willcox, University of Southampton, UK

- L. Windsley, Organic Research Centre, UK

- F. Yutong, Centre for Evidence-Based Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, China

References

- World Health Organization. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; Wellcome Trust & HM Government: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rabaan, A.A.; Alhumaid, S.; Al Mutair, A.; Garout, M.; Abulhamayel, Y.; Halwani, M.A.; Alestad, J.H.; Al Bshabshe, A.; Sulaiman, T.; AlFonaisan, M.K.; et al. Application of artificial intelligence in combating high antimicrobial resistance rates. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9789241509763. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, E.Y.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Martinez, E.M.; Pant, S.; Gandra, S.; Levin, S.A.; Goossens, H.; Laxminarayan, R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E3463–E3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in EUROPE 2018; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2024. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/reducing-antimicrobial-resistance-accelerated-efforts-are-needed-meet-eu-targets (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. JIACRA III—Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance in Bacteria from Humans and Animals; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/third-joint-interagency-antimicrobial-consumption-and-resistance-analysis-report (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- EMA. European Medicines Agency. 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/veterinary-regulatory-overview/antimicrobial-resistance-veterinary-medicine/european-surveillance-veterinary-antimicrobial-consumption-esvac-2009-2023 (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Global. Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance in Bacteria from Humans and Food-Producing Animals (JIACRA IV—2019−2021). 2024. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-consumption-and-resistance-bacteria-humans-and-food-producing (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Berthe, F.C.J.; Bouley, T.; Karesh, W.B.; Legall, I.C.; Machalaba, C.C.; Plante, C.A.; Seifman, R.M. One Health: Operational Framework for Strengthening Human, Animal, and Environmental Public Health Systems at Their Interface; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; No. 122980; pp. 1–152. [Google Scholar]

- Viñes, J.; Cuscó, A.; Napp, S.; Alvarez, J.; Saez-Llorente, J.L.; Rosàs-Rodoreda, M.; Francino, O.; Migura-Garcia, L. Transmission of Similar Mcr-1 Carrying Plasmids among Different Escherichia coli Lineages Isolated from Livestock and the Farmer. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; WHO Regional Office for Europe. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Europe, 2023 Data: Executive Summary; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, U. The cost of antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.N.; Zhu, S.; Cooper, N.; Little, P.; Tarrant, C.; Hickman, M.; Yao, G. The economic burden of antibiotic resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Research Agenda for Antimicrobial Resistance in Human Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-research-agenda-for-antimicrobial-resistance-in-human-health (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- World Health Organization; UNEP United Nations Environment Programme; World Organisation for Animal Health. A One Health Priority Research Agenda for Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.-Y.; Wu, R.-H.; Logue, M.; Blondel, C.; Lai, L.Y.W.; Stuart, B.; Flower, A.; Fei, Y.-T.; Moore, M.; Shepherd, J.; et al. Andrographis paniculata (Chuān Xīn Lián) for symptomatic relief of acute respiratory tract infections in adults and children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anheyer, D.; Cramer, H.; Lauche, R.; Saha, F.J.; Dobos, G. Herbal medicine in children with respiratory tract infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.; Cramer, H.; Klose, P.; Lauche, R.; Gass, F.; Dobos, G.; Langhorst, J. Herbal medicine for cough: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Forsch. Komplementärmedizin/Res. Complement. Med. 2015, 22, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamin, W.; Funk, P.; Seifert, G.; Zimmermann, A.; Lehmacher, W. EPs 7630 is Effective and Safe in Children under 6 Years with Acute Respiratory Tract Infections: Clinical Studies Revisited. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2018, 34, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçe, Ş.; Dörtkardeşler, B.E.; Yurtseven, A.; Kurugöl, Z. Effectiveness of Pelargonium sidoides in pediatric patients diagnosed with uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection: A single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 3019–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsch-Völk, M.; Barrett, B.; Linde, K. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. JAMA 2015, 313, 618–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, R.; Balla, A. Complementary and alternative medicine for prevention and treatment of the common cold. Can. Fam. Physician 2011, 57, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Veldman, L.B.; Belt-Van Zoen, E.; Baars, E.W. Mechanistic Evidence of Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Wall. ex Nees, Pelargonium sidoides DC.; Echinacea Species and a Combination of Hedera helix L.; Primula veris L./Primula elatior L. and Thymus vulgaris L./Thymus zygis L. in the Treatment of Acute, Uncomplicated Respiratory Tract Infections: A Systematic Literature Review and Expert Interviews. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamre, H.J.; Glockmann, A.; von Ammon, K.; Riley, D.S.; Kiene, H. Efficacy of homoeopathic treatment: Systematic review of meta-analyses of randomised placebo-controlled homoeopathy trials for any indication. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiermayer, P.; Frass, M.; Peinbauer, T.; Ellinger, L. Evidence-based homeopathy and veterinary homeopathy, and its potential to help overcome the anti-microbial resistance problem-an overview. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2020, 162, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneis, K.C.; Gandjour, A. Economic evaluation of Sinfrontal® in the treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis in adults. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2009, 7, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, H.J.; Glockmann, A.; Schwarz, R.; Riley, D.S.; Baars, E.W.; Kiene, H.; Kienle, G.S. Antibiotic use in children with acute respiratory or ear infections: Prospective observational comparison of anthroposophic and conventional treatment under routine primary care conditions. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 243801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin. DEGAM Leitlinie Nr. 11. Akuter und Chronischer Husten; AWMF-Register-Nr. 053-013; DEGAM: Berlin, Germany, November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stuck, B.A.; Beule, A.; Jobst, D.; Klimek, L.; Laudien, M.; Lell, M.; Vogl, T.J.; Popert, U. Leitlinie „Rhinosinusitis “–Langfassung. Hno 2018, 66, 38–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nice Guideline Cough (Acute): Antimicrobial Prescribing [NG120]. (February 2019). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng120 (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- BfArM. Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (2025). Available online: https://www.bfarm.de/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- EMA. European Medicines Agency. 2025. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/herbal-medicinal-products (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2001:311:0067:0128:en:PDF (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- van Wietmarschen, H.; van Steenbergen, N.; van der Werf, E.; Baars, E. Effectiveness of herbal medicines to prevent and control symptoms of urinary tract infections and to reduce antibiotic use: A literature review. Integr. Med. Res. 2022, 11, 100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannek, J.; Pannek-Rademacher, S.; Jus, M.S.; Wöllner, J.; Krebs, J. Usefulness of classical homeopathy for the prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in individuals with chronic neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2019, 42, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witteman, L.; van Wietmarschen, H.A.; van der Werf, E.T. Complementary medicine and self-care strategies in women with (recurrent) urinary tract and vaginal infections: A cross-sectional study on use and perceived effectiveness in the Netherlands. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerlink, I.; Ellinger, L.; Bakker, E.J.; Lantinga, E.A. Homeopathy as replacement to antibiotics in the case of Escherichia coli diarrhoea in neonatal piglets. Homeopathy 2010, 99, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, J.; Barros, M.M.; Araújo, D.; Campos, A.M.; Oliveira, R.; Silva, S.; Almeida, C. Swine enteric colibacillosis: Current treatment avenues and future directions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 981207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathie, R.T.; Clausen, J. Veterinary homeopathy: Systematic review of medical conditions studied by randomised trials controlled by other than placebo. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalcaburio, R.; Machado Filho, L.C.P.; Honorato, L.A.; Nelton, A.Ã. Homeopathic remedies in a semi-intensive alternative system of broiler production. Int. J. High Dilution Res. 2009, 8, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchieri Jr, A.; Turco, W.C.P.; Paiva, J.B.; Oliveira, G.H.; Sterzo, E.V. Evaluation of isopathic treatment of Salmonella enteritidis in poultry. Homeopathy 2006, 95, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadipour, M.M.; Habibi, G.H.; Ghorashinejad, A.; Olyaie, A.; Torki, M. Evaluation of the Homeopathic Remedies. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2011, 10, 2102–2105. [Google Scholar]

- Low, C.X.; Tan, L.T.-H.; Ab Mutalib, N.-S.; Pusparajah, P.; Goh, B.-H.; Chan, K.-G.; Letchumanan, V.; Lee, L.-H. Unveiling the impact of antibiotics and alternative methods for animal husbandry: A review. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, C.H.; Morfin, L.L.; Lopez, B.B. Preliminary research for testing Baptisia tinctoria 30c effectiveness against salmonellosis in first and second quality broiler chickens. Br. Homeopath. J. 1998, 87, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, C.; Listar, V.G.; Bonamin, L.V. Development of broiler chickens after treatment with thymulin 5cH: A zoo technical approach. Homeopathy 2012, 101, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velkers, F.C.; Te Loo, A.J.H.; Madin, F.; Van Eck, J.H.H. Isopathic and pluralist homeopathic treatment of commercial broilers with experimentally induced colibacillosis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2005, 78, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.; Punniamurthy, N.; Kumar, S.K. Ethno-veterinary practices for animal health and the associated Medicinal Plants from 24 Locations in 10 States of India. Res. J. Vet. Sci 2017, 3, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zeise, J.; Fritz, J. Use and efficacy of homeopathy in prevention and treatment of bovine mastitis. Open Agric. 2019, 4, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, E.W.; Zoen, E.B.V.; Breitkreuz, T.; Martin, D.; Matthes, H.; Schoen-Angerer, T.V.; Soldner, G.; Vagedes, J.; Wietmarschen, H.V.; Patijn, O.; et al. The contribution of complementary and alternative medicine to reduce antibiotic use: A narrative review of health concepts, prevention, and treatment strategies. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 5365608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, E.T.; Duncan, L.J.; von Flotow, P.; Baars, E.W. Do NHS GP surgeries employing GPs additionally trained in integrative or complementary medicine have lower antibiotic prescribing rates? Retrospective cross-sectional analysis of national primary care prescribing data in England in 2016. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeschli, A.; Schmidt, A.; Ammann, W.; Schurtenberger, P.; Maurer, E.; Walkenhorst, M. Einfluss eines komplementärmedizinischen telefonischen Beratungssystems auf den Antibiotikaeinsatz bei Nutztieren in der Schweiz. Complement. Med. Res. 2019, 26, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orjales, I.; López-Alonso, M.; Rodríguez-Bermúdez, R.; Rey-Crespo, F.; Villar, A.; Miranda, M. Is lack of antibiotic usage affecting udder health status of organic dairy cattle? J. Dairy Res. 2016, 83, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Silva, J.E.; Santos Souza, C.A.; da Silva, T.B.; Gomes, I.A.; de Carvalho Brito, G.; de Souza Araújo, A.A.; de Lyra-Júnior, D.P.; da Silva, W.B.; da Silva, F.A. Use of herbal medicines by elderly patients: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 59, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsdottir, T.J.; Örlygsdóttir, B.; Vilhjálmsson, R. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in Iceland: Results from a national health survey. Scand. J. Public Health 2020, 48, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokladnikova, J.; Selke-Krulichova, I. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by the general population in the Czech Republic: A follow-up study. Complement. Med. Res. 2018, 25, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, D.; Lorenc, A.; Morris, R.; Feder, G.; Little, P.; Hollinghurst, S.; Mercer, S.W.; MacPherson, H. Complementary medicine use, views, and experiences: A national survey in England. BJGP Open 2018, 2, bjgpopen18X101614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellec, F.; Manoli, C.; Joybert, M.D. Alternative medicines on the farm: A study of dairy farmers’ experiences in France. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 563957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, N.; Francis, N.A.; Butler, C.C. Reducing uncertainty in managing respiratory tract infections in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2010, 60, e466–e475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliford, M.C.; Moore, M.V.; Little, P.; Hay, A.D.; Fox, R.; Prevost, A.T.; Juszczyk, D.; Charlton, J.; Ashworth, M. Safety of reduced antibiotic prescribing for self limiting respiratory tract infections in primary care: Cohort study using electronic health records. BMJ 2016, 354, i3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwels, K.B.; Dolk, F.C.K.; Smith, D.R.; Robotham, J.V.; Smieszek, T. Actual versus ‘ideal’antibiotic prescribing for common conditions in English primary care. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73 (Suppl. 2), 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh, C.; Mamphweli, S.; Meyer, E.; Okoh, A. Antibiotic use in agriculture and its consequential resistance in environmental sources: Potential public health implications. Molecules 2018, 23, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcox, M.; Donovan, E.; Hu, X.Y.; Elboray, S.; Jerrard, N.; Roberts, N.; Santer, M. Views regarding use of complementary therapies for acute respiratory infections: Systematic review of qualitative studies. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 50, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, D.; Blanco-Penedo, I.; De Joybert, M.; Sundrum, A. How target-orientated is the use of homeopathy in dairy farming?—A survey in France, Germany and Spain. Acta Vet. Scand. 2019, 61, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, M.A. Epidemiologische Untersuchungen zur Tiergesundheit in Schweinezuchtbeständen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Managementfaktoren und des Einsatzes von Antibiotika und Homöopathika. Ph.D. Dissertation, Tierärztliche Hochsch, Hannover, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.jpiamr.eu/projects/gifts-amr/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Available online: https://louisbolk.nl/media/pdf/Research-Agenda.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Humphrey-Murto, S.; Lee, S.H.; Gottlieb, M.; Horsley, T.; Shea, B.; Fournier, K.; Tran, C.; Chan, T.; Wood, T.J.; Cate, O.T. Protocol for an extended scoping review on the use of virtual nominal group technique in research. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, M.L.; Tai, C.J.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Hu, X.Y.; Heinrich, M. Clinical phytopharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1353483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Themes | Research Priorities | Prioritized Research Projects for the Next 10 Years | Contribution to the WHO Global Research Agenda (2023) * | Contribution to the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH Global Research Agenda (2023) ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient preferences and stakeholders’ needs for non-antibiotic prevention and treatment strategies for infections |

|

|

|

|

| Safety, (cost-)effectiveness, benefits/risks ratios, and benefits/costs ratios of TCIH strategies in human and veterinary medicine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Use of limited evidence and real-world evidence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

| Implementation and information tools |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baars, E.W.; Weiermayer, P.; Szőke, H.P.; van der Werf, E.T., on behalf of the GIFTS-AMR Group. The Introduction of the Global Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Healthcare (TCIH) Research Agenda on Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Added Value to the WHO and the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH 2023 Research Agendas on Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14010102

Baars EW, Weiermayer P, Szőke HP, van der Werf ET on behalf of the GIFTS-AMR Group. The Introduction of the Global Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Healthcare (TCIH) Research Agenda on Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Added Value to the WHO and the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH 2023 Research Agendas on Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaars, Erik W., Petra Weiermayer, Henrik P. Szőke, and Esther T. van der Werf on behalf of the GIFTS-AMR Group. 2025. "The Introduction of the Global Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Healthcare (TCIH) Research Agenda on Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Added Value to the WHO and the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH 2023 Research Agendas on Antimicrobial Resistance" Antibiotics 14, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14010102

APA StyleBaars, E. W., Weiermayer, P., Szőke, H. P., & van der Werf, E. T., on behalf of the GIFTS-AMR Group. (2025). The Introduction of the Global Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Healthcare (TCIH) Research Agenda on Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Added Value to the WHO and the WHO/FAO/UNEP/WOAH 2023 Research Agendas on Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics, 14(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14010102