Nanocellulose-Based Materials for Water Purification

Abstract

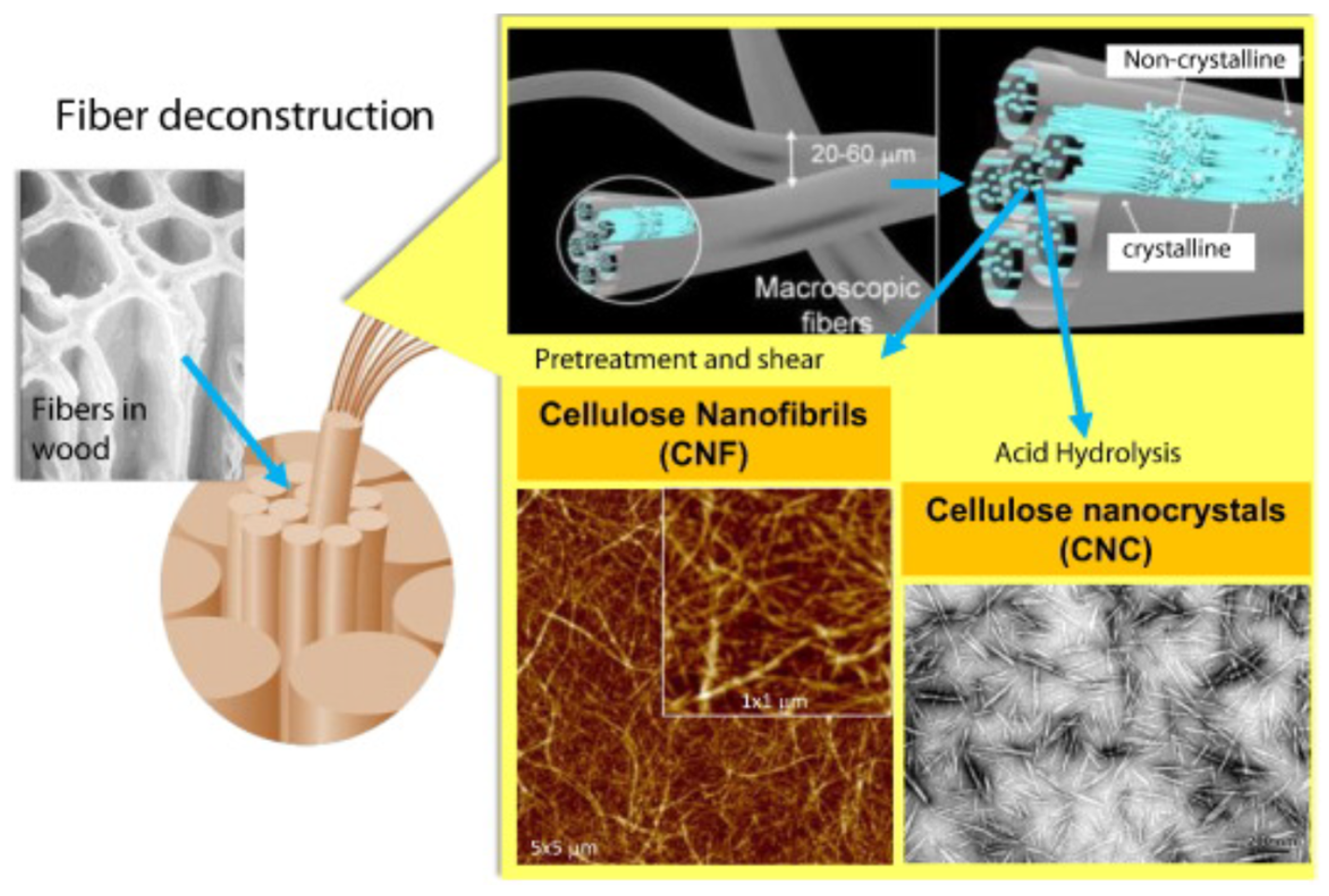

:1. Introduction

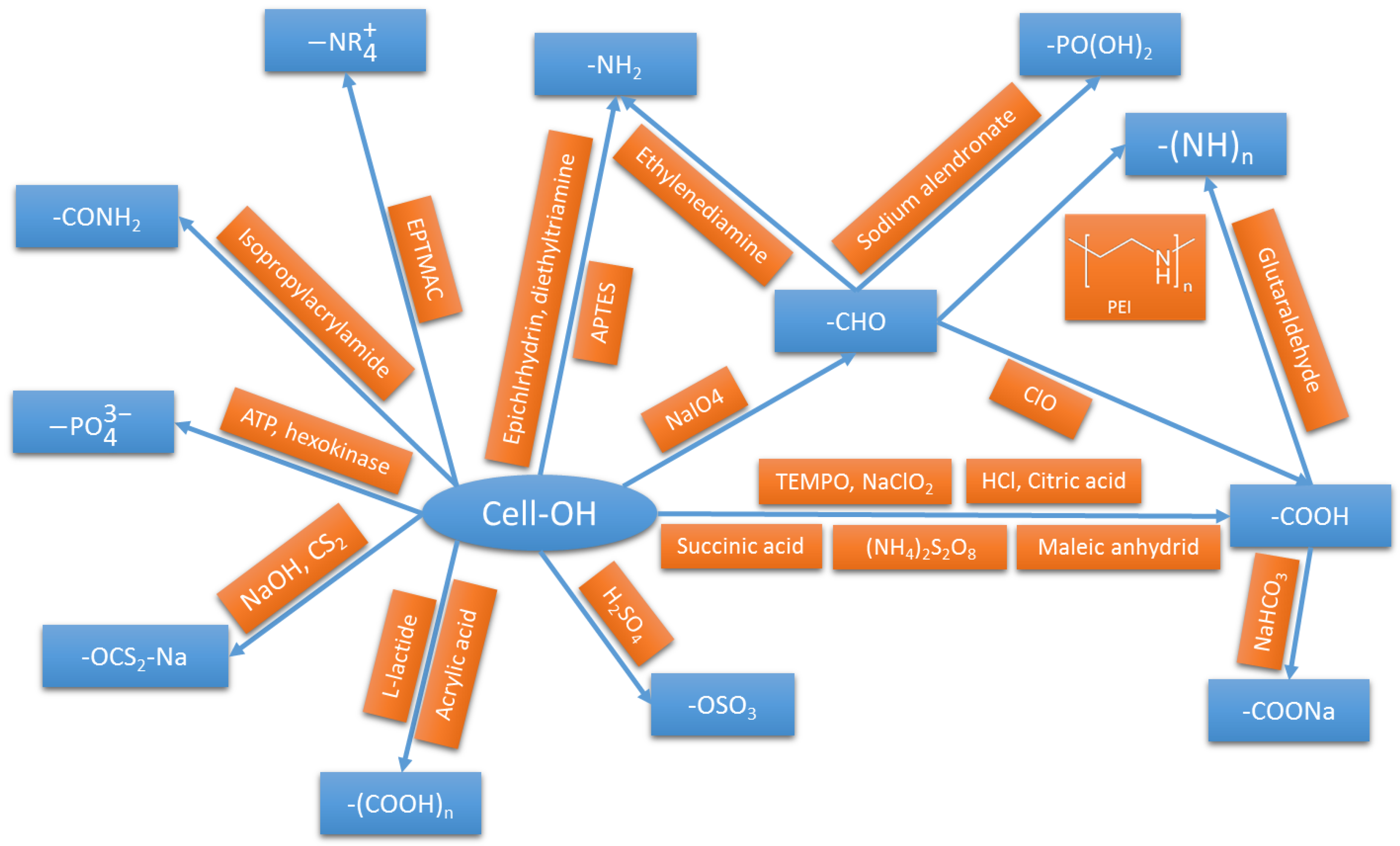

2. Sorption of Pollutants by Functionalized Nanocellulose

2.1. Biosorption and Adsorption Mechanisms

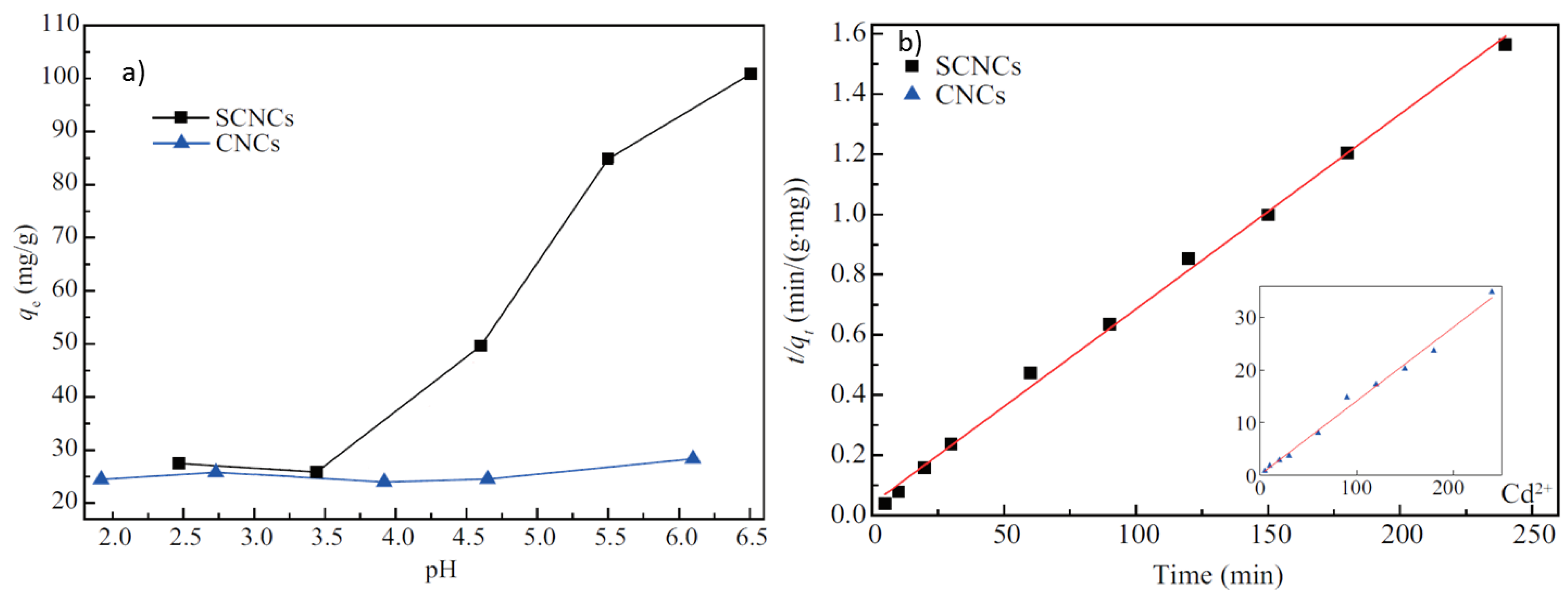

2.2. Uptake and Removal of Heavy Metal Species from Water

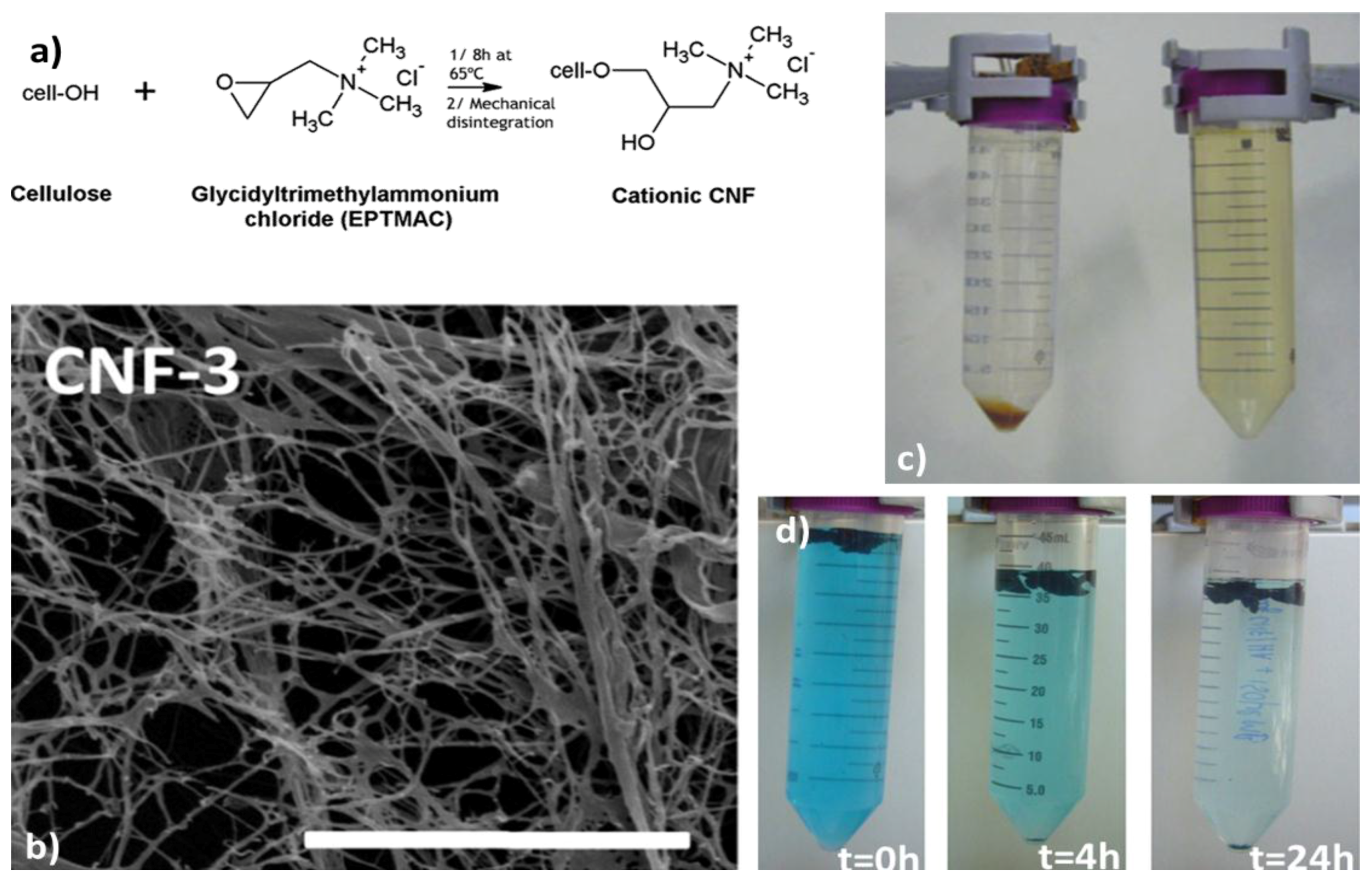

Removal of Organic Pollutants

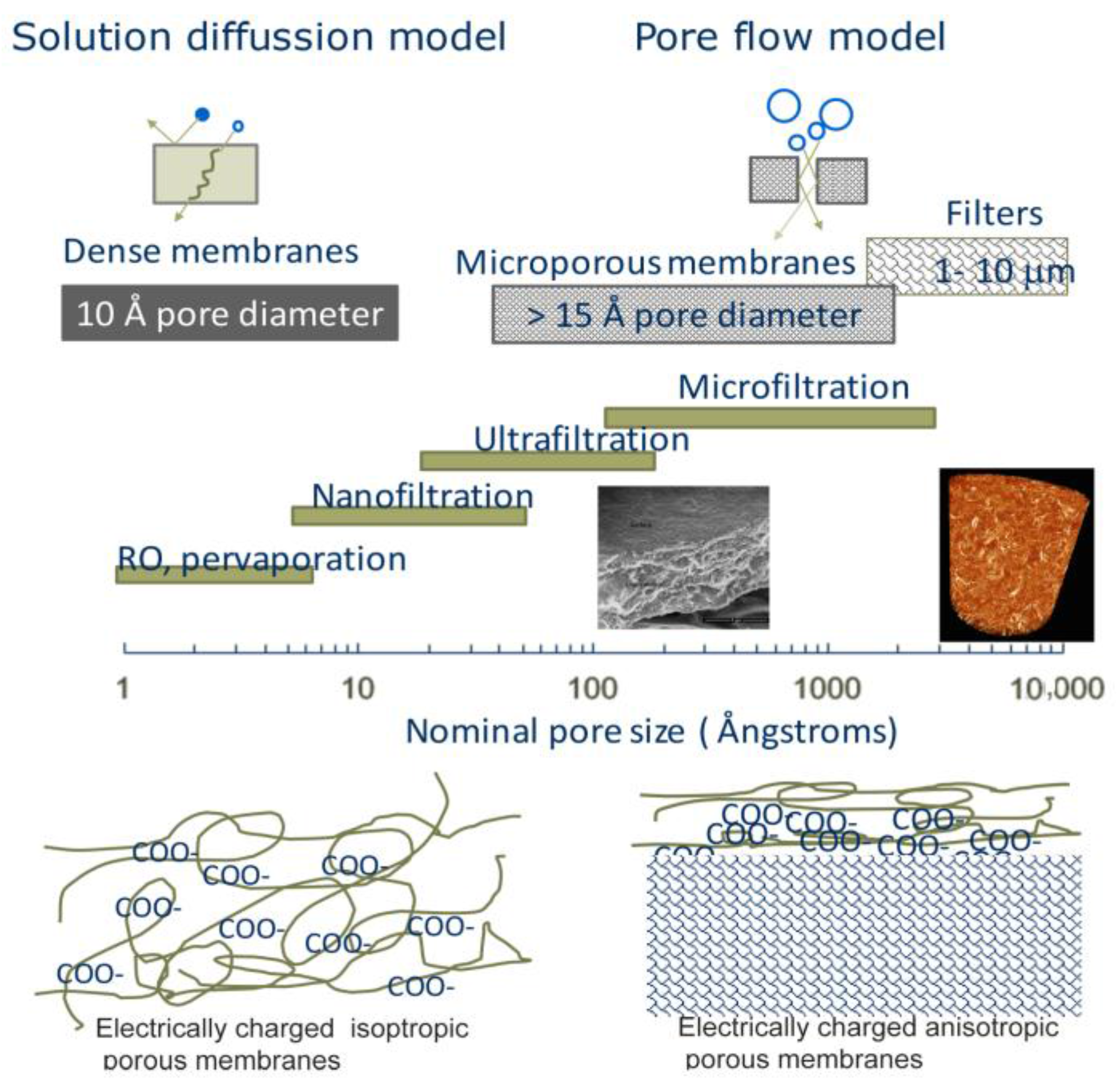

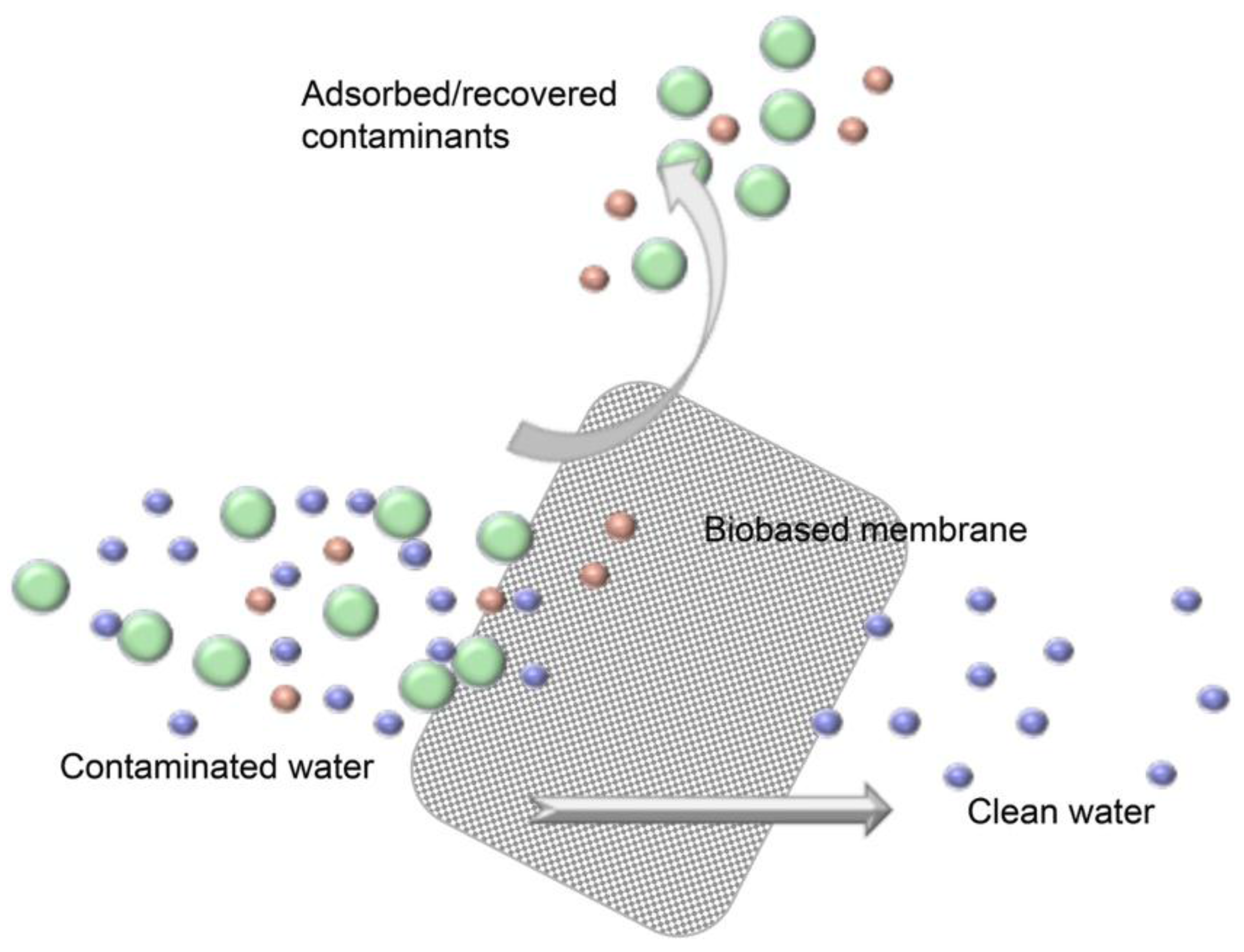

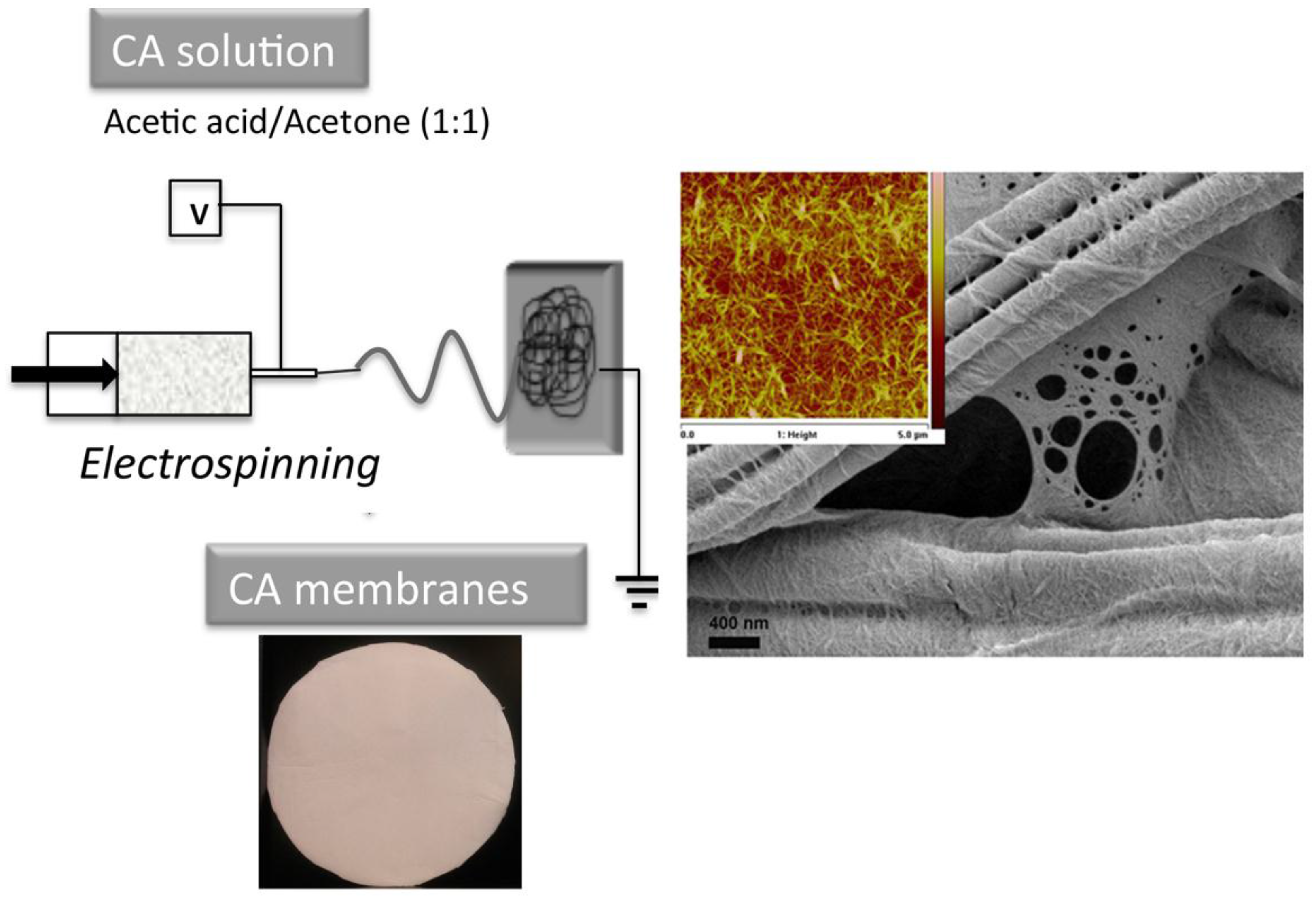

3. Nanocellulose-Based Water Purification Membranes and Filters

Processing and Properties of Nanocellulose-Based Water Purification Materials

4. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richard, W.B. Membrane Technology and Applications, 3rd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, J. Basic Principles of Membrane Technology; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ulbricht, M. Advanced functional polymer membranes. Polymer 2006, 47, 2217–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.W.; de Lannoy, C.-F.; Wiesner, M.R. Cellulose nanomaterials in water treatment technologies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5277–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, Y.; Lucia, L.A.; Rojas, O.J. Cellulose nanocrystals: Chemistry, self-assembly, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3479–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, Y. Key advances in the chemical modification of nanocelluloses. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1519–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hestrin, S.; Schramm, M. Synthesis of cellulose by Acetobacter xylinum. II. Preparation of freeze-dried cells capable of polymerizing glucose to cellulose. Biochem. J. 1954, 58, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas, C.; Nypelö, T.; Rodriguez-Abreu, C.; Carrillo, C.; Rojas, O.J. Nanocellulose properties and applications in colloids and interfaces. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 19, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, K.; Kobayashi, M. Theoretical evaluation of three-dimensional elastic constants of native and regenerated celluloses: Role of hydrogen bonds. Polymer 1991, 32, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šturcová, A.; Davies, G.R.; Eichhorn, S.J. Elastic modulus and stress-transfer properties of tunicate cellulose whiskers. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohmood, I.; Lopes, C.B.; Lopes, I.; Ahmad, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Pereira, E. Nanoscale materials and their use in water contaminants removal—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 1239–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, J.; Harrisson, S.; Chen, V. Strategies for controlling biofouling in membrane filtration systems: Challenges and opportunities. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 4567–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehaqui, H.; Zhou, Q.; Ikkala, O.; Berglund, L.A. Strong and tough cellulose Nano paper with high specific surface area and porosity. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3638–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehaqui, H.; de Larraya, U.P.; Liu, P.; Pfenninger, N.; Mathew, A.P.; Zimmermann, T.; Tingaut, P. Enhancing adsorption of heavy metal ions onto biobased nanofibers from waste pulp residues for application in wastewater treatment. Cellulose 2014, 21, 2831–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banavath, H.N.; Bhardwaj, N.K.; Ray, A.K. A comparative study of the effect of refining on charge of various pulps. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 4544–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Božic, M.; Liu, P.; Mathew, A.P.; Kokol, V. Enzymatic phosphorylation of cellulose nanofibers to new highly-ions adsorbing, flame-retardant and hydroxyapatite-growth induced natural nanoparticles. Cellulose 2014, 21, 2713–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isogai, A.; Saito, T.; Fukuzumi, H. TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volesky, B. Biosorption and me. Water Res. 2007, 41, 4017–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Arora, J.K.; Sinha, T.J.M.; Srivastava, S. Functionalization of nanocrystalline cellulose for decontamination of Cr(III) and Cr(VI) from aqueous system: Computational modeling approach. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2014, 16, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E. Affinity membranes: A 10-year review. J. Membr Sci. 2000, 179, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Oksman, K.; Mathew, A.P. Surface adsorption and self-assembly of Cu(II) ions on TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers in aqueous media. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 464, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Sehaqui, H.; Tingaut, P.; Wichser, A.; Oksman, K.; Mathew, A.P. Cellulose and chitin nanomaterials for capturing silver ions (Ag+) from water via surface adsorption. Cellulose 2014, 21, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehaqui, H.; Mautner, A.; de Larraya, U.P.; Pfenninger, N.; Tingaut, P.; Zimmermann, T. Cationic cellulose nanofibers from waste pulp residues and their nitrate, fluoride, sulphate and phosphate adsorption properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 135, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Burger, C.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B. Nanofibrous microfiltration membrane based on cellulose nanowhiskers. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Guan, S.; Sato, A.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, R.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B. Nanofibrous microfiltration membranes capable of removing bacteria, viruses and heavy metal ions. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 446, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.; Shukry, N.; El-Sakhawy, M. Carboxymethyl cellulose-G-poly(2-(dimethylamino) ethyl methacrylate) hydrogel as adsorbent for dye removal. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 73, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Li, W.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Q. Amino-functionalized nanocrystalline cellulose as an adsorbent for anionic dyes. Cellulose 2015, 22, 2443–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman; Kardam, A.; Gera, M.; Jain, V.K. A novel reusable nanocomposite for complete removal of dyes, heavy metals and microbial load from water based on nanocellulose and silver nano-embedded pebbles. Environ. Technol. 2016, 36, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Dobryden, I.; Rydén, J.; Öberg, S.; Holmgren, A.; Mathew, A.P. Adsorption Behavior of Cellulose and Its Derivatives toward Ag(I) in Aqueous Medium: An AFM, Spectroscopic, and DFT Study. Langmuir 2015, 31, 12390–12400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, V.K.; Voicu, S.I. Recent advances in cellulose and chitosan based membranes for water purification: A concise review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 146, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Sèbe, G.; Rentsch, D.; Zimmermann, T.; Tingaut, P. Ultralightweight and flexible silylated nanocellulose sponges for the selective removal of oil from water. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2659–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yeh, T.-M.; Wang, Z.; Yang, R.; Wang, R.; Ma, H.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B. Nanofiltration membranes prepared by interfacial polymerization on thin-film nanofibrous composite scaffold. Polymer 2014, 55, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, D.W.; Birkinshaw, C.; O’Dwyer, T.F. Heavy metal adsorbents prepared from the modification of cellulose: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 6709–6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan Ngah, W.S.; Hanafiah, M.A.K.M. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater by chemically modified plant wastes as adsorbents: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3935–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Uber die Adsorption in Lösungen. Z. Phys. Chem. 1906, 57, 385–470. [Google Scholar]

- Volesky, B.; Holan, Z.R. Biosorption of heavy metals. Biotechnol. Prog. 1995, 11, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksu, Z. Application of biosorption for the removal of organic pollutants: A review. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 997–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvil, D.; Volesky, B. Advances in the biosorption of heavy metals. Trends Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Ion-exchange behavior of carboxylate groups in fibrous cellulose oxidized by the TEMPO-mediated system. Carbohydr. Polym. 2005, 61, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B. Ultrafine cellulose nanofibers as efficient adsorbents for removal of UO22+ in water. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tong, S.; Ge, M.; Wu, L.; Zuo, J.; Cao, C.; Song, W. Adsorption of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution by carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokkanen, S.; Repo, E.; Sillanpää, M. Removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions by succinic anhydride modified mercerized nanocellulose. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 223, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Alam, M.N.; van de Ven, T.G.M. Highly charged nanocrystalline cellulose and dicarboxylated cellulose from periodate and chlorite oxidized cellulose fibers. Cellulose 2013, 20, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi, A.; Safari, S.; Yang, H.; van de Ven, T.G.M. Copper removal using electrosterically stabilized nanocrystalline cellulose. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 11301–11308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardam, A.; Raj, K.R.; Srivastava, S.; Srivastava, M.M. Nanocellulose fibers for biosorption of cadmium, nickel, and lead ions from aqueous solution. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2014, 16, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Chen, S.; Shi, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, W.; Wang, H. Adsorption of Cu(II) and Pb(II) onto diethylenetriamine-bacterial cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 75, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Borrell, P.F.; Božič, M.; Kokol, V.; Oksman, K.; Mathew, A.P. Nanocelluloses and their phosphorylated derivatives for selective adsorption of Ag+, Cu2+ and Fe3+ from industrial effluents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 294, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, S.S.; Deepa, B.; Abraham, E.; Girija, N.; Geetha, P.; Jacob, L.; Koshy, M. Biosorption of Cd(II) from aqueous solution using xanthated nano banana cellulose: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 98, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulmanu, M.; Marañón, E.; Fernández, Y.; Castrillón, L.; Anger, I.; Dumitriu, D. Removal of Copper and Cadmium Ions from Diluted Aqueous Solutions by Low Cost and Waste Material Adsorbents. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2003, 142, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, M.; Cranston, E.D.; Westman, G.; Gray, D.G. Cationic surface functionalization of cellulose nanocrystals. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 2238–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirviö, J.A.; Hasa, T.; Leiviskä, T.; Liimatainen, H.; Hormi, O. Bisphosphonate nanocellulose in the removal of vanadium(V) from water. Cellulose 2016, 23, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, R.R.; Sumi, K.; Fujii, N.; Matsumura, M. Mercury removal from wastewater using porous cellulose carrier modified with polyethyleneimine. Water Res. 1996, 30, 2488–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, J.; Wada, M.; Kuga, S. Steric stabilization of a cellulose microcrystal suspension by poly(ethylene glycol) grafting. Langmuir 2001, 17, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biçak, N.; Sherrington, D.C.; Senkal, B.F. Graft copolymer of acrylamide onto cellulose as mercury selective sorbent. React. Funct. Polym. 1999, 41, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppe, J.O.; Habibi, Y.; Rojas, O.J.; Venditti, R.A.; Johansson, L.; Efimenko, K.; Österberg, M.; Laine, J. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) brushes grafted from cellulose nanocrystals via surface-initiated single-electron transfer living radical polymerization. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geay, M.; Marchetti, V.; Clément, A.; Loubinoux, B.; Gérardin, P. Decontamination of synthetic solutions containing heavy metals using chemically modified sawdusts bearing polyacrylic acid chains. J. Wood Sci. 2000, 46, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlü, G.; Gürdag, G.; Özgümüs, S. Competitive Removal of Heavy Metal Ions by Cellulose Graft Copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 2034–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffin, A.-L.; Habibi, Y.; Raquez, J.-M.; Dubois, P. Polyester-grafted cellulose nanowhiskers: A new approach for tuning the microstructure of immiscible polyester blends. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 3364–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffin, A.-L.; Raquez, J.-M.; Duquesne, E.; Siqueira, G.; Habibi, Y.; Dufresne, A.; Dubois, P. From interfacial ring-opening polymerization to melt processing of cellulose nanowhisker-filled polylactide-based nanocomposites. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 2456–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, B.; Dorgan, J.R.; Hollingsworth, L.O. Supra-molecular ecobionanocomposites based on polylactide and cellulosic nanowhiskers: synthesis and properties. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 2013–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, L.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Zhang, W. Acrylic acid grafted and acrylic acid/sodium humate grafted bamboo cellulose nanofibers for Cu2+ adsorption. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 55195–55201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zang, G.-L.; Shi, C.; Yu, H.-Q.; Sheng, G.-P. A novel adsorbent TEMPO-mediated oxidized cellulose nanofibrils modified with PEI: Preparation, characterization, and application for Cu(II) removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 316, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, R.R.; Sumi, K.; Matsumura, M. Improved metal affinity of chelating adsorbents through graft polymerization. Water Res. 1999, 33, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zheng, Q.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Cai, Z.; Chen, L.; Gong, S. Mechanically strong fully biobased anisotropic cellulose aerogels. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 96518–96526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhalfaoui, B.; Aziz, A.; Elandaloussi, E.H.; Ouali, M.S.; de Ménorval, L.C. Succinate-bonded cellulose: A regenerable and powerful sorbent for cadmium-removal from spiked high-hardness groundwater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nada, A.A.M.A.; Hassan, M.L. Phosphorylated Cation-Exchangers from Cotton Stalks and Their Constituents. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 89, 2950–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokkanen, S.; Repo, E.; Suopajärvi, T.; Liimatainen, H.; Niinimaa, J.; Sillanpää, M. Adsorption of Ni(II), Cu(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solutions by amino modified nanostructured microfibrillated cellulose. Cellulose 2014, 21, 1471–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofei, S.; Schmidt, W.; Kurunczi, L.; Simon, Z. A review of QSAR for dye affinity for cellulose fibres. Dyes Pigments 2000, 47, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batmaz, R.; Mohammed, N.; Zaman, M.; Minhas, G.; Berry, R.M.; Tam, K.C. Cellulose nanocrystals as promising adsorbents for the removal of cationic dyes. Cellulose 2014, 21, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, F.; Wang, E.; Min, Y.; Huang, Q.; Pang, L.; Ma, T. Effective removal of cationic dyes using carboxylate-functionalized cellulose nanocrystals. Chemosphere 2016, 141, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.C.W.; Hrapovic, S.; Lam, E.; Liu, Y.; Male, K.B.; Mahmoud, K.A.; Luong, J.H.T. Characteristics and properties of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals prepared from a novel one-step procedure. Small 2011, 7, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Male, K.B.; Nesterenko, P.N.; Brabazon, D.; Paull, B.; Luong, J.H.T. Adsorption and desorption of methylene blue on porous carbon monoliths and nanocrystalline cellulose. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 8796–8804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, H.-Y.; Zhang, D.-Z.; Lu, F.-F.; Yao, J. New Approach for Single-Step Extraction of Carboxylated Cellulose Nanocrystals for Their Use as Adsorbents and Flocculants. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2632–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, A.; Butchosa, N.; Berglund, L.A.; Zhou, Q. Surface quaternized cellulose nanofibrils with high water absorbency and adsorption capacity for anionic dyes. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Sun, Q.; Xu, Q.; Xu, Y. Adsorptive removal of anionic dyes form aqueous solutions using microgel based on nanocellulose and polyvinylamine. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 197, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, L.; Liao, Q.; Chen, X.; Qian, Z.; Shen, J.; Liang, J.; Yao, J. Functionalization of cellulose with hyperbranched polyethylenimine for selective dye adsorption and separation. Cellulose 2016, 23, 3785–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehaqui, H.; de Larraya, U.P.; Tingaut, P.; Zimmermann, T. Humic acid adsorption onto cationic cellulose nanofibers for bioinspired removal of copper(II) and a positively charged dye. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 5294–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le-Minh, N.; Khan, S.J.; Drewes, J.E.; Stuetz, R.M. Fate of antibiotics during municipal water recycling treatment processes. Water Res. 2010, 44, 4295–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.K.; Letchford, K.; Wasserman, B.Z.; Ye, L.; Hamad, W.Y.; Burt, H.M. The use of nanocrystalline cellulose for the binding and controlled release of drugs. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Espino-Pérez, E.; Bras, J.; Ducruet, V.; Guinault, A.; Dufresne, A.; Domenek, S. Influence of chemical surface modification of cellulose nanowhiskers on thermal, mechanical, and barrier properties of poly(lactide) based bionanocomposites. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 3144–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, M.; Haldar, S.; Basha, S. Nanocrystalline cellulose for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride from water via biosorption: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 84, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghi, S.P.; Tiong, D.; Berry, R.M.; Tam, K.C. Comparative release studies of two cationic model drugs from different cellulose nanocrystal derivatives. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 88, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Burger, C.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B. Highly permeable polymer membranes containing directed channels for water purification. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Burger, C.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B. Ultra-fine cellulose nanofibers: New nano-scale materials for water purification. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 7507–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, L.A.; Jalvo, B.; Rosal, R.; Mathew, A.P. Superhydrophilic anti-fouling electrospun cellulose acetate membranes coated with chitin nanocrystals for water filtration. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 510, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, A.; Lee, K.; Tammelin, T.; Mathew, A.P.; Nedoma, A.J.; Li, K.; Bismarck, A. Cellulose nanopapers as tight aqueous ultra-filtration membranes. React. Funct. Polym. 2015, 86, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, A.; Lee, K.-Y.; Lahtinen, P.; Hakalahti, M.; Tammelin, T.; Li, K.; Bismarck, A. Nanopapers for organic solvent nanofiltration. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 5778–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mautner, A.; Maples, H.A.; Kobkeatthawin, T.; Kokol, V.; Karim, Z.; Li, K.; Bismarck, A. Phosphorylated nanocellulose papers for copper adsorption from aqueous solutions. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 1861–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, A.; Maples, H.A.; Sehaqui, H.; Zimmermann, T.; de Larraya, U.P.; Mathew, A.P.; Lai, C.Y.; Li, K.; Bismarck, A. Nitrate removal from water using a nanopaper ion-exchanger. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2016, 2, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metreveli, G.; Wågberg, L.; Emmoth, E.; Belák, S.; Strømme, M.; Mihranyan, A. A Size-Exclusion Nanocellulose Filter Paper for Virus Removal. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 1546–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, Z.; Mathew, A.P.; Kokol, V.; Wei, J.; Grahn, M. High-flux affinity membranes based on cellulose nanocomposites for removal of heavy metal ions from industrial effluents. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 20644–20653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, Z.; Claudpierre, S.; Grahn, M.; Oksman, K.; Mathew, A.P. Nanocellulose based functional membranes for water cleaning: Tailoring of mechanical properties, porosity and metal ion capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 514, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, Z.; Mathew, A.P.; Grahn, M.; Mouzon, J.; Oksman, K. Nanoporous membranes with cellulose nanocrystals as functional entity in chitosan: Removal of dyes from water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 112, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: www.nanoselect.eu (accessed on 4 March 2017).

- Nanocellulose Water Purification Membranes. Available online: http://www.more.se/en/news/2016/nanocellulose-water-purification-membranes/ (accessed on 4 March 2017).

| Functionalization Nature and Route | Contaminant | pH | Qmax (mg/g) | Reference | Qmax of Comparably Functionalized Cellulose (mg/g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (CNF-OH obtained through mechanical treatment) | Cd2+ | 5.5 | 11 | [46] | ||

| Ni+ | 11 | |||||

| Pb+ | 10 | |||||

| CNC-SO3− (sulfuric acid hydrolysis) | Ag+ | 6.5 | 34 | [22] | ||

| CNC-PO42− (phosphorylation of CNC) | Ag+ | 4 | 136 | [48] | [67] | |

| Cu2+ | 117 | 19 | ||||

| Fe3+ | 115 | |||||

| CNC-COOH (Succinic anhydride) | Pb2+ | 5.5 | 458 | [42] | [68] | |

| Cd2+ | 335 | 179 | ||||

| CNC-COOH (sodium periodate/chlorite) | Cu2+ | 4 | 185 | [45] | ||

| CNF-COOH (TEMPO) | Cu2+ | 6.2–6.5 | 112 | [14,41] | ||

| Ni2+ | 49 | |||||

| Cr(III) | 58 | |||||

| Zn2+ | 67 | |||||

| UO22+ | 167 | |||||

| CNF-(PO(OH)2)2 | VO3− | 2 | 194 | [52] | ||

| CNF-NH2 (reaction with APTES) | Ni(II) | 5 | 179 | [66] | ||

| Cu(II) | 163 | |||||

| Cd(II) | 388 | |||||

| NC-ROCS2—Na (reaction with C2) | Cd(II) | 6 | 154 | [49] | ||

| CNC-NH2 (reaction with K2S2O8 and ethylenediamine) | Cr(VI) | 3 | [19] | |||

| BC-NH2 (reaction with epichlrorhydrin and diethylenetramine) | Pb2+ | 4.5 | 84 | [47] | ||

| Cu2+ | 63 | |||||

| CNC-NH2 (grafting with PEG-NH2) | Hg2+ | [54] | 288 | [53] | ||

| CNC-CONH2 (grafting of isopropylacrylamide) | Hg2+ | [56] | 710 | [55] | ||

| CNC-PLA (grafting) | Cu2+ | 4.9 | [59,60,61] | 104 | [57,58] | |

| Ni2+ | 5.9 | 168 | ||||

| Cd2+ | 5.7 | 97 | ||||

| Pb2+ | 4.5 | 49.7 | ||||

| TEMPO CNF-PEI | Cu2+ | 5 | 52.3 | [63,64] | 19.2 | [64] |

| CNF-CMC (crosslinked using butanetetracarboxylic acid) | Ag+ | 106 | [65] | |||

| Cu2+ | 74.8 | |||||

| Pb2+ | 111.5 | |||||

| Hg2+ | 131.4 |

| Functionalization Nature and Route | Contaminant | pH | Qmax (mg/g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNC-SO3− (sulfuric acid hydrolysis) | Methylene blue | 9 | 118 | [70] |

| Tetracycline hydrochloride | 7 | [80] | ||

| CNC-COOH (TEMPO) | Methylene blue | 9 | 769 | [70] |

| CNC-COOH (esterification with maleic anhydrid) | Crystal violet | 6 | 244 | [71] |

| CNC-COOH (reaction with ammonium persulfate) | Methylene blue | 7 | 101 | [73] |

| CNC-COOH (reaction with citric acid) | Methylene blue | 7 | 135 | [74] |

| CNC-NH2 (oxidation with NaIO4 followed by reaction with ethylenediamine) | Acid red GR | 4.7 | 556 | [27] |

| CNF-NR4+ (reaction with EPTMAC) | Congo red | 664 | [75] | |

| Acid green 25 | 683 | [75] | ||

| Humic acid | 310 | [77] | ||

| CNC-NH2 (grafted with PVAm) | Acid red GR | 9 | 869 | [76] |

| Congo red 4BS | 1469 | |||

| Light yellow K-4G | 1250 | |||

| CNC-NH2 (oxidation with NaIO4 followed by grafting with hyperbranched PEI) | Congo red | 2100 | [77] | |

| Basic yellow | 1860 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Voisin, H.; Bergström, L.; Liu, P.; Mathew, A.P. Nanocellulose-Based Materials for Water Purification. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7030057

Voisin H, Bergström L, Liu P, Mathew AP. Nanocellulose-Based Materials for Water Purification. Nanomaterials. 2017; 7(3):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7030057

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoisin, Hugo, Lennart Bergström, Peng Liu, and Aji P. Mathew. 2017. "Nanocellulose-Based Materials for Water Purification" Nanomaterials 7, no. 3: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7030057

APA StyleVoisin, H., Bergström, L., Liu, P., & Mathew, A. P. (2017). Nanocellulose-Based Materials for Water Purification. Nanomaterials, 7(3), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7030057