Molecular Dynamics Study on the Mechanical Properties of Bilayer Silicon Carbide

Abstract

1. Introduction

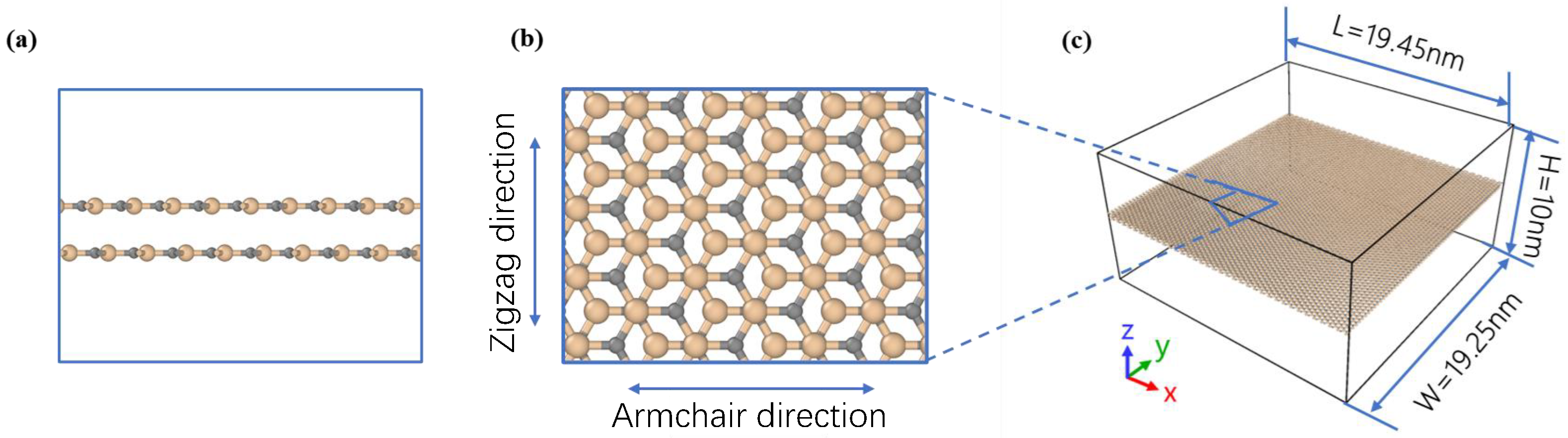

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

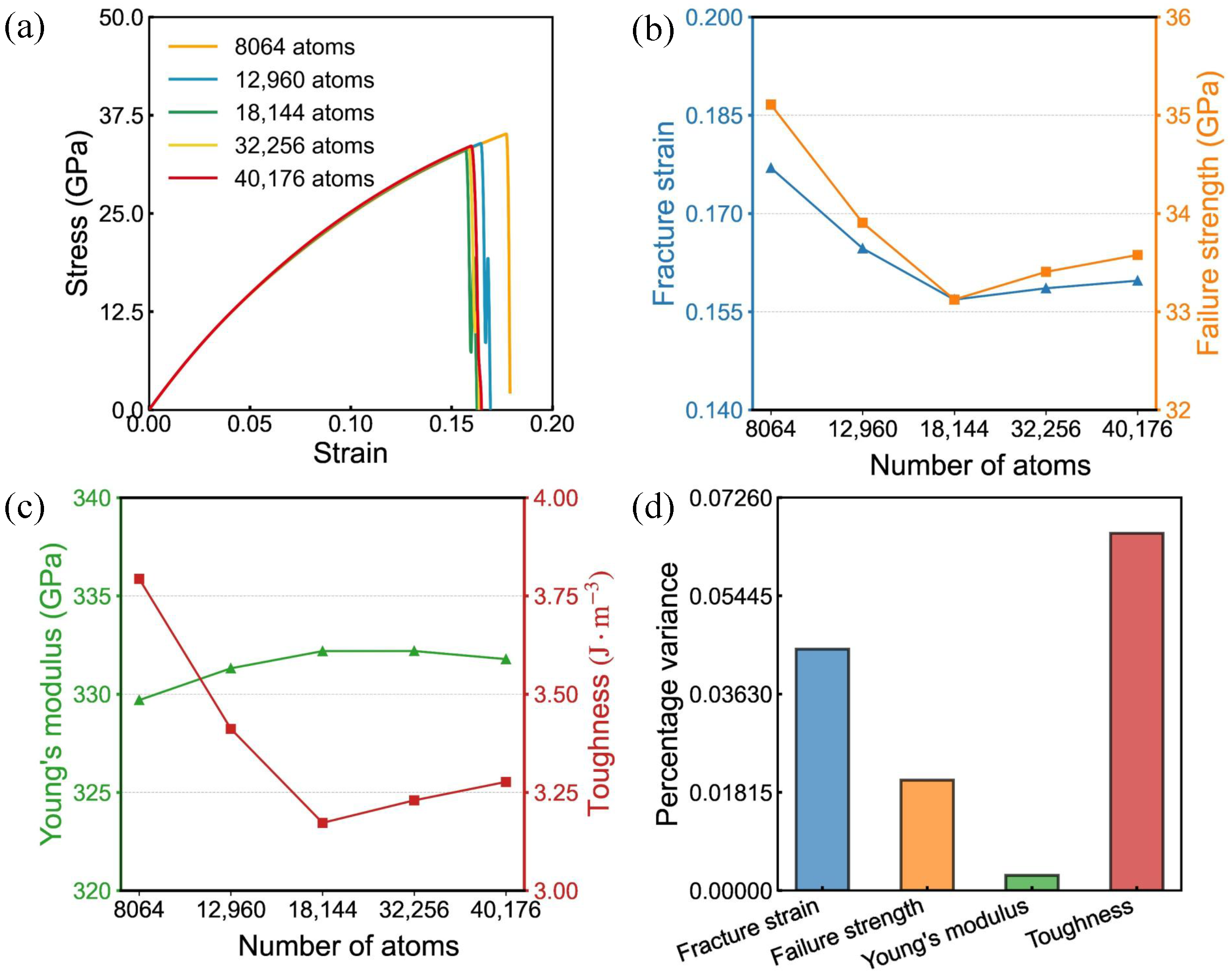

3.1. Size Effect

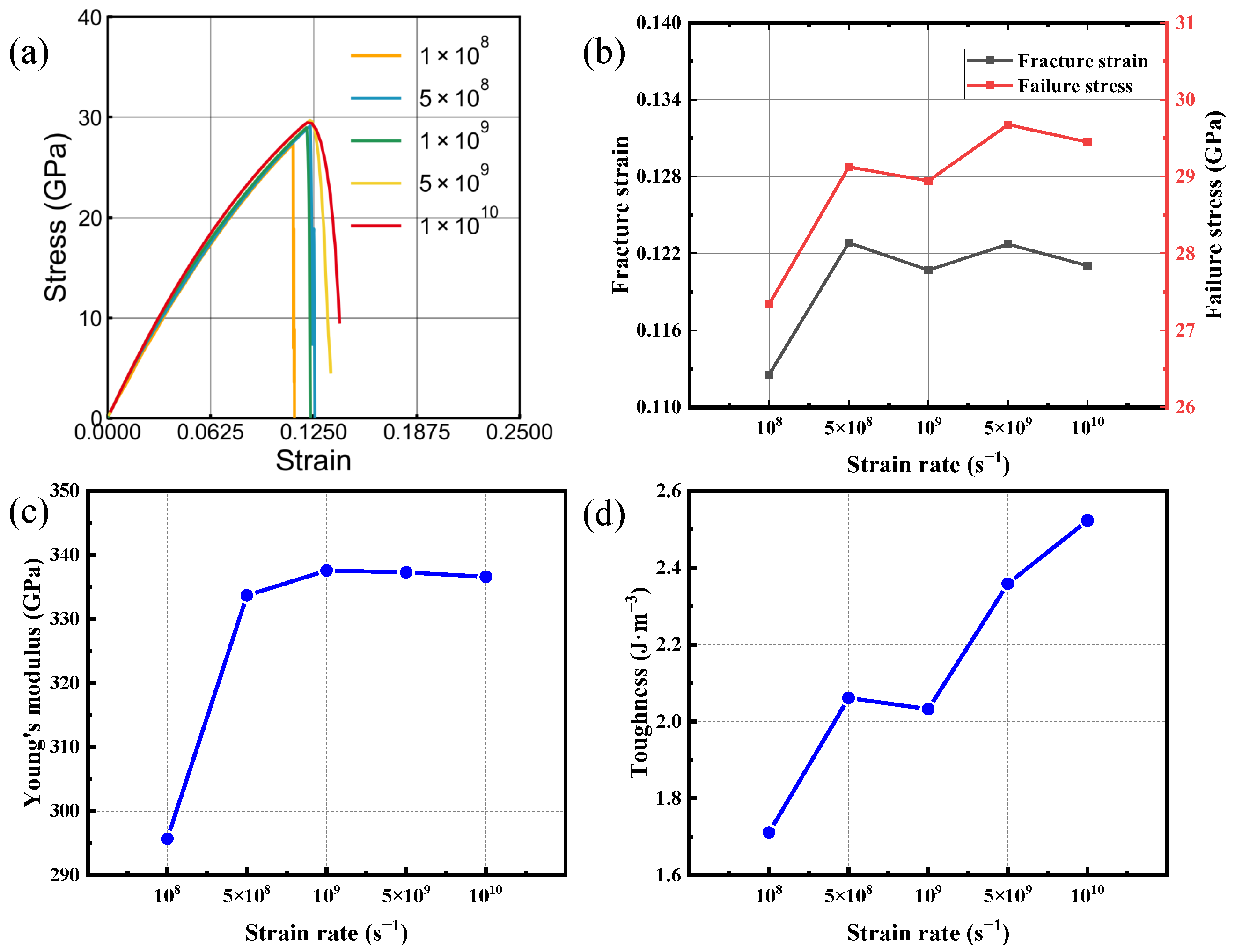

3.2. Strain Rate Effect

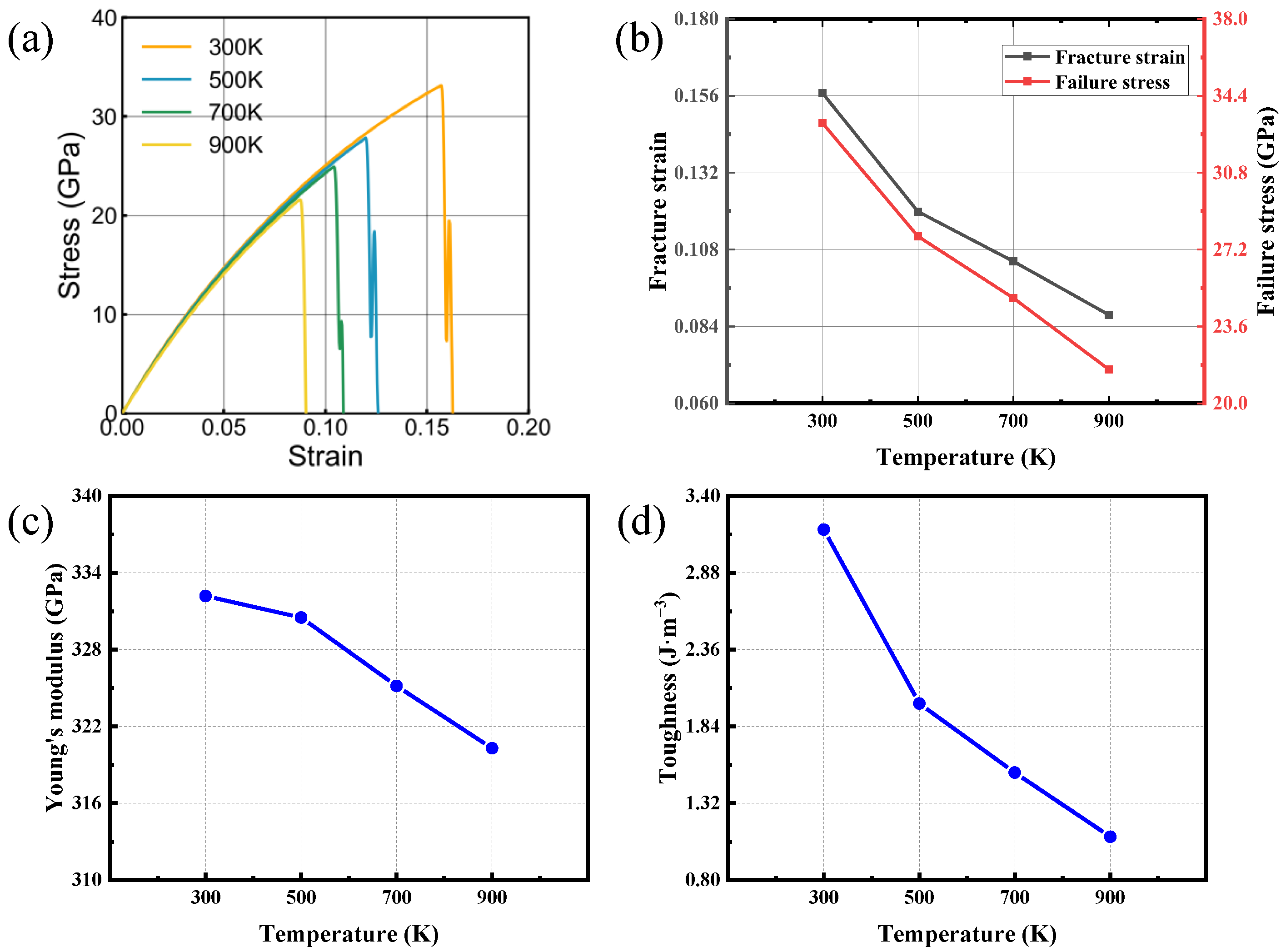

3.3. Temperature Effect

3.4. The Vacancy-Defect Effect

3.5. Cracks and Toughness

3.5.1. Effect of Cracks on Mechanical Properties

3.5.2. Deformation and Fracture Behavior

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Momeni, K.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y.; Paul, S.; Neshani, S.; Yilmaz, D.E.; Shin, Y.K.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, J.W.; Park, H.S.; et al. Multiscale Computational Understanding and Growth of 2D Materials: A Review. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, C.; Zhou, P. 2D Semiconductors for Specific Electronic Applications: From Device to System. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2022, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemme, M.C.; Wagner, S.; Lee, K.; Fan, X.; Verbiest, G.J.; Wittmann, S.; Lukas, S.; Dolleman, R.J.; Niklaus, F.; van der Zant, H.S.J.; et al. Nanoelectromechanical Sensors Based on Suspended 2D Materials. Research 2020, 2020, 8748602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daus, A.; Vaziri, S.; Chen, V.; Köroğlu, Ç.; Grady, R.W.; Bailey, C.S.; Lee, H.R.; Schauble, K.; Brenner, K.; Pop, E. High-Performance Flexible Nanoscale Transistors Based on Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Nat. Electron. 2021, 4, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Ning, J.; Wang, P.; Ye, Y.; Luo, J.; Yin, A.; Ren, Z.; Liu, H.; Qi, X.; et al. Ultra-Thin Highly Sensitive Electronic Skin for Temperature Monitoring. Polymers 2024, 16, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejhon, M.; Zhou, X.; Lavini, F.; Zanut, A.; Popovich, F.; Schellack, L.; Witek, L.; Coelho, P.; Kunc, J.; Riedo, E. Giant Increase of Hardness in Silicon Carbide by Metastable Single Layer Diamond-Like Coating. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2204562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Shin, D.; Sberna, P.M.; van der Kolk, R.; Cupertino, A.; Bessa, M.A.; Norte, R.A. High-Strength Amorphous Silicon Carbide for Nanomechanics. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2306513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, A.S.J.; Akbar, M.S.; Islam, M.S.; Park, J. Temperature- and Defect-Induced Uniaxial Tensile Mechanical Behaviors and the Fracture Mechanism of Two-Dimensional Silicon Germanide. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 21861–21871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Zarkadoula, E.; Crespillo, M.L.; Mu, W.; Liu, P. Distinctive Features of Structural Evolution and Thermodynamic Response in Wide-Bandgap Semiconductors Driven by Intense Electronic Excitation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2026, 718, 164873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabi, S.; Kadel, K. Two-Dimensional Silicon Carbide: Emerging Direct Band Gap Semiconductor. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabi, S.; Guler, Z.; Brearley, A.J.; Benavidez, A.D.; Luk, T.S. The Creation of True Two-Dimensional Silicon Carbide. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Yong, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Kuang, Y.; Li, X. Gas-Sensing Properties of the SiC Monolayer and Bilayer: A Density Functional Theory Study. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 12364–12373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, K.J.; Alharbi, S.A.R.; Musa, M.R.K.; Lovell, S.H.; Akridge, Z.A.; Yu, M. Insight into the Stacking and the Species-Ordering Dependences of Interlayer Bonding in SiC/GeC Polar Heterostructures. Nanotechnology 2022, 33, 155706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Jeon, I.; Kim, H. Heterogeneous Integration of Wide Bandgap Semiconductors and 2D Materials: Processes, Applications, and Perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2411108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, W.s.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, J. Thermal Stability of Si/SiC/Ta-C Composite Coatings and Improvement of Tribological Properties through High-Temperature Annealing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, F.; Han, H.; Zhang, P. A Review of SiC Sensor Applications in High-Temperature and Radiation Extreme Environments. Sensors 2024, 24, 7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Du, S.; Zhang, Y. The Molecular Dynamic Studies of Thermal Conductivity of SiC Ceramic Derived from β/α Phase Transformation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Z.L. Wear-Resisting and Stable 4H-SiC/Cu-Based Tribovoltaic Nanogenerators for Self-Powered Sensing in a Harsh Environment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 55192–55200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Mahamiya, V.; Shukla, A. Characterization of Silicon Carbide Biphenylene Network through ${G}_{0}{W}_{0}$-BSE Calculations. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 195305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peivaste, I.; Alahyarizadeh, G.; Minuchehr, A.; Aghaie, M. Comparative Study on Mechanical Properties of Three Different SiC Polytypes (3C, 4H and 6H) under High Pressure: First-principle Calculations. Vacuum 2018, 154, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labed, M.; Moon, J.Y.; Kim, S.I.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Venkata Prasad, C.; Bae, S.H.; Rim, Y.S. 2D Embedded Ultrawide Bandgap Devices for Extreme Environment Applications. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 30153–30183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.; Kim, D.G.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Ha, S.; Yang, H.; Jang, Y.; Yoon, J.; et al. A Universal 2D-on-SiC Platform for Heterogeneous Integration of Epitaxial III-N Membranes. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadz3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, P.; Krijnen, G.; Roozeboom, F. Precision in Harsh Environments. Microsystems Nanoeng. 2016, 2, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Y.; Luo, R.; Lei, B.; Ji, W.; Zhou, W. Controlled Fabrication of Freestanding Monolayer SiC by Electron Irradiation. Chin. Phys. B 2024, 33, 086802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbisan, L.; Scalise, E.; Marzegalli, A. Evolution and Intersection of Extended Defects and Stacking Faults in 3C-SiC Layers on Si (001) Substrates by Molecular Dynamics Simulations: The Forest Dislocation Case. Phys. Status Solidi (B) 2022, 259, 2100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, T.D.; Knobloch, J.L.; Hernández-Charpak, J.N.; Hoogeboom-Pot, K.M.; Nardi, D.; Yazdi, S.; Chao, W.; Anderson, E.H.; Tripp, M.K.; King, S.W.; et al. Full Characterization of Ultrathin 5-Nm Low-k Dielectric Bilayers: Influence of Dopants and Surfaces on the Mechanical Properties. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 073603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Wang, J. Simulation of Mechanical Properties of Two-Dimensional Silicon Carbide Film with Stochastically Distributed Vacancy Defects. J. Chem. Phys. 2025, 162, 204703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, K.; Huang, L.; Shu, H.; Zhang, G.; Mu, W.; Zhang, H.; Qin, H.; Zhang, G. Impacts of Defects on the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of SiC and GeC Monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 32378–32386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.S.M.J.; Islam, M.S.; Ferdous, N.; Park, J.; Bhuiyan, A.G.; Hashimoto, A. Anisotropic Mechanical Behavior of Two Dimensional Silicon Carbide: Effect of Temperature and Vacancy Defects. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 125073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, A.; Ritchie, R.O. Toughness and Strength of Nanocrystalline Graphene. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, L.; Fan, F.; Zeng, Z.; Peng, C.; Loya, P.E.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Fracture Toughness of Graphene. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.C.; Yan, C.; Ma, L.; Hu, N.; Chen, M.W. Effect of Defects on Fracture Strength of Graphene Sheets. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2012, 54, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Y.P.; Li, S.; Yang, Q.; Li, D.; Pantelides, S.T.; Lin, J. Engineering the Crack Structure and Fracture Behavior in Monolayer MoS2 By Selective Creation of Point Defects. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2200700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, P.M.; Lam, V.T.; Osamu, S.; Tran, H.T.T. The Influence of Twist Angle on the Electronic and Phononic Band of 2D Twisted Bilayer SiC. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 32641–32647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.Q.; Nguyen, D.T. Atomistic Simulations of Pristine and Defective Hexagonal BN and SiC Sheets under Uniaxial Tension. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 615, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwande, D.; Brennan, C.J.; Bunch, J.S.; Egberts, P.; Felts, J.R.; Gao, H.; Huang, R.; Kim, J.S.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; et al. A Review on Mechanics and Mechanical Properties of 2D Materials—Graphene and Beyond. arxXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.01555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Mahamiya, V.; Shukla, A. Defect-Driven Tunable Electronic and Optical Properties of Two-Dimensional Silicon Carbide. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 235311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; in ’t Veld, P.J.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D.; et al. LAMMPS—A Flexible Simulation Tool for Particle-Based Materials Modeling at the Atomic, Meso, and Continuum Scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tersoff, J. New Empirical Approach for the Structure and Energy of Covalent Systems. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 6991–7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tersoff, J. Carbon defects and defect reactions in silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 1757–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and Analysis of Atomistic Simulation Data with OVITO—The Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2009, 18, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimpton, S. Fast Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular Dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.P.; Heider, Y. A Review on Brittle Fracture Nanomechanics by All-Atom Simulations. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Mitra, S.; Motalab, M.; Bose, P. Investigation on the Mechanical Properties and Fracture Phenomenon of Silicon Doped Graphene by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 31318–31332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Guo, W.; Chen, C. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Tensile Elongation of Carbon Nanotubes: Temperature and Size Effects. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 155436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque Chowdhury, E.; Rahman, M.H.; Hong, S. Tensile Strength and Fracture Mechanics of Two-Dimensional Nanocrystalline Silicon Carbide. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 197, 110580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, A.G. Carbon: A New View of Its High-Temperature Behavior. Science 1978, 200, 763–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasolino, A.; Los, J.H.; Katsnelson, M.I. Intrinsic Ripples in Graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 858–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Aluru, N.R. Temperature and Strain-Rate Dependent Fracture Strength of Graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 108, 064321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannizzo, A.; Giordano, S. Thermal Effects on Fracture and the Brittle-to-Ductile Transition. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 107, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewapriya, M.A.N.; Srikantha Phani, A.; Rajapakse, R.K.N.D. Influence of Temperature and Free Edges on the Mechanical Properties of Graphene. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 21, 065017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurkov, S.N. Kinetic Concept of the Strength of Solids. Int. J. Fract. 1984, 26, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Gu, Y.T. Mechanical Properties of Graphene: Effects of Layer Number, Temperature and Isotope. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2013, 71, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantab, R.; Shenoy, V.B.; Ruoff, R.S. Anomalous Strength Characteristics of Tilt Grain Boundaries in Graphene. Science 2010, 330, 946–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Lu, J. Intrinsic Strength and Failure Behaviors of Graphene Grain Boundaries. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2704–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsen, A.W.; Brown, L.; Levendorf, M.P.; Ghahari, F.; Huang, P.Y.; Havener, R.W.; Ruiz-Vargas, C.S.; Muller, D.A.; Kim, P.; Park, J. Tailoring Electrical Transport Across Grain Boundaries in Polycrystalline Graphene. Science 2012, 336, 1143–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, J.; Yin, H.; Shi, X.; Yang, R.; Dresselhaus, M. The Nature of Strength Enhancement and Weakening by Pentagon–Heptagon Defects in Graphene. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagri, A.; Kim, S.P.; Ruoff, R.S.; Shenoy, V.B. Thermal Transport across Twin Grain Boundaries in Polycrystalline Graphene from Nonequilibrium Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3917–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lee, G.; Cho, K. Thermal Transport in Graphene and Effects of Vacancy Defects. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 115460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, A.A., VI. The Phenomena of Rupture and Flow in Solids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Contain. Pap. Math. Phys. Character 1921, 221, 163–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peng, Q.; Huang, A.; Qin, L.; Shu, C.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Cai, X.; Chen, X.-J. Molecular Dynamics Study on the Mechanical Properties of Bilayer Silicon Carbide. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16030207

Peng Q, Huang A, Qin L, Shu C, Li J, Li H, Zheng L, Cai X, Chen X-J. Molecular Dynamics Study on the Mechanical Properties of Bilayer Silicon Carbide. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(3):207. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16030207

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Qing, Anyi Huang, Lang Qin, Chaoxi Shu, Jiale Li, Hongyang Li, Lihang Zheng, Xintian Cai, and Xiao-Jia Chen. 2026. "Molecular Dynamics Study on the Mechanical Properties of Bilayer Silicon Carbide" Nanomaterials 16, no. 3: 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16030207

APA StylePeng, Q., Huang, A., Qin, L., Shu, C., Li, J., Li, H., Zheng, L., Cai, X., & Chen, X.-J. (2026). Molecular Dynamics Study on the Mechanical Properties of Bilayer Silicon Carbide. Nanomaterials, 16(3), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16030207