Tailoring the Microstructure and Properties of HiPIMS-Deposited DLC-Cr Nanocomposite Films via Chromium Doping

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Films Deposition

2.2. Film Characterization

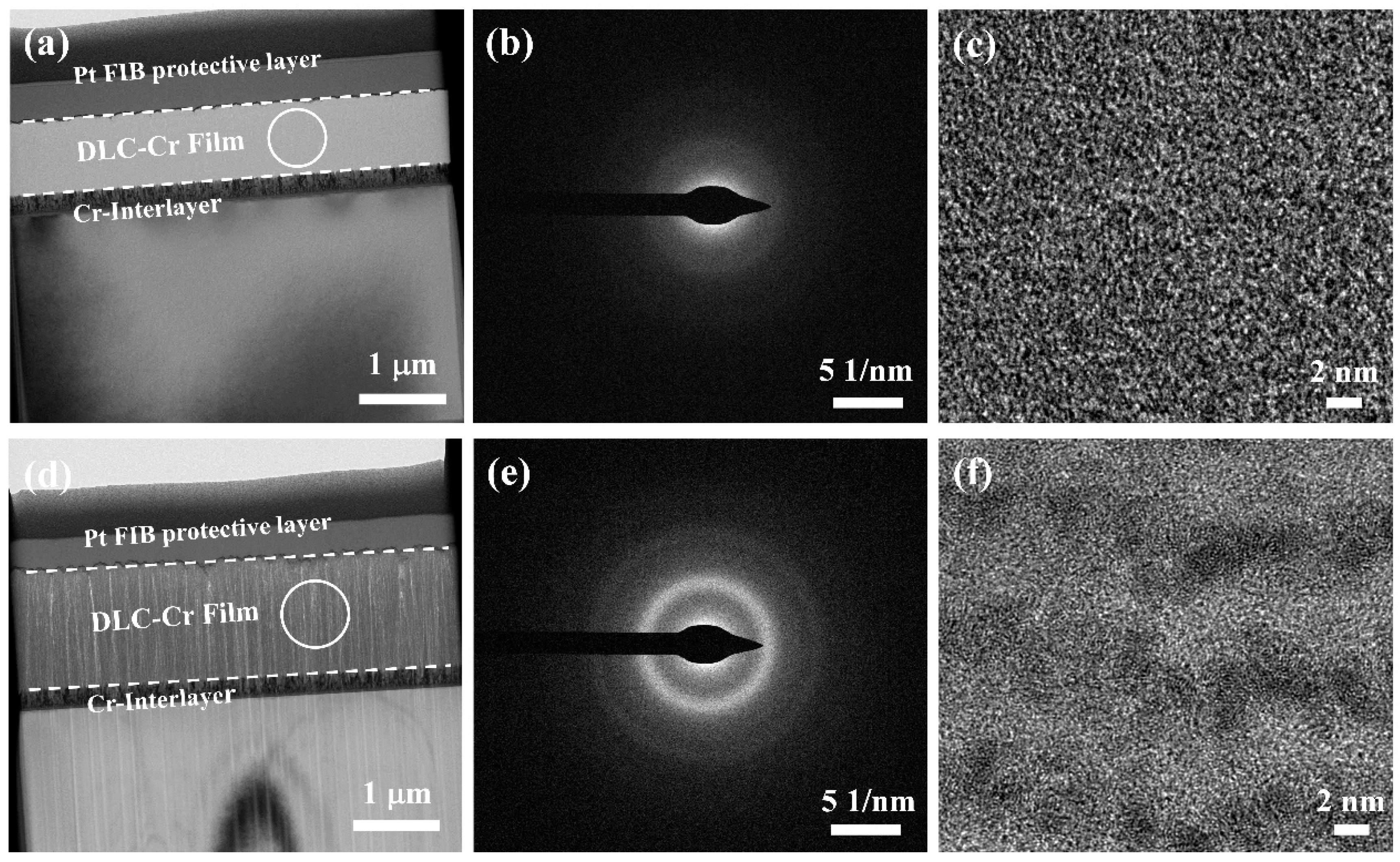

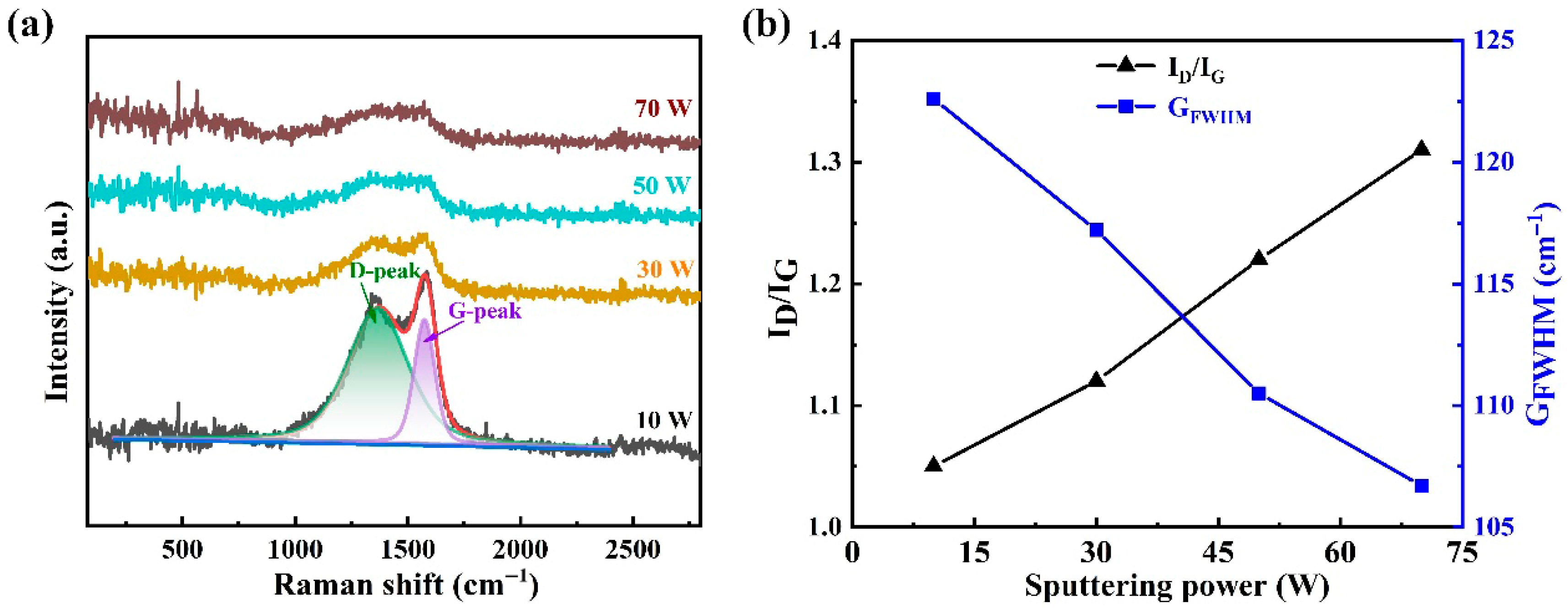

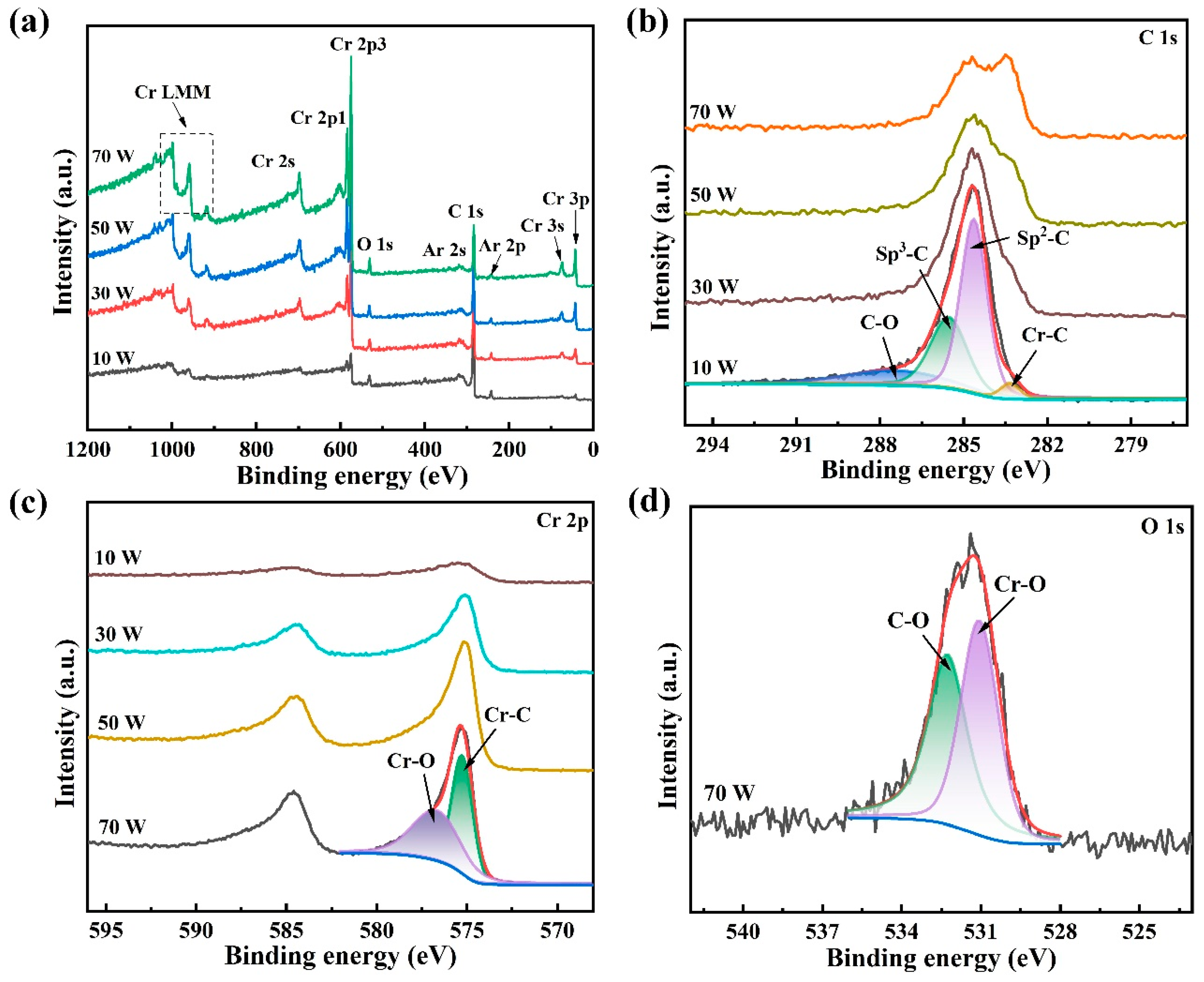

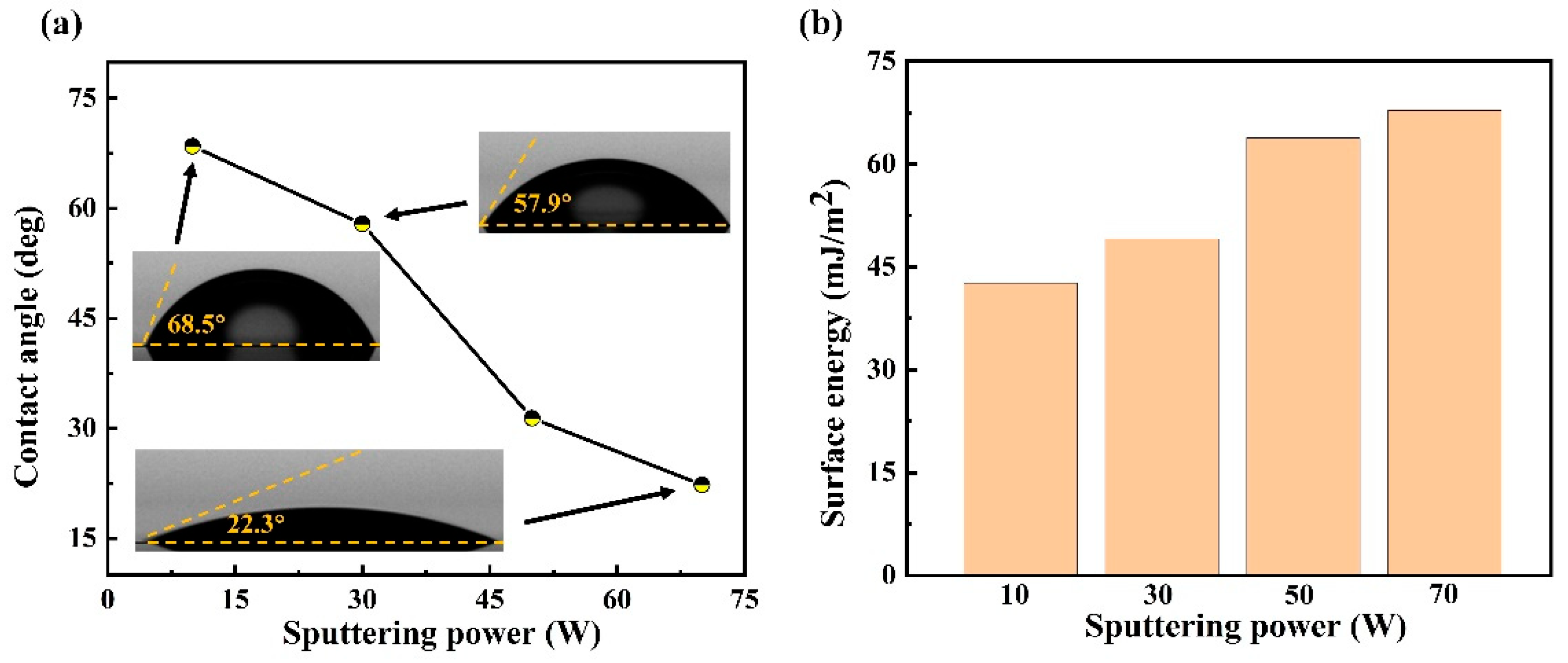

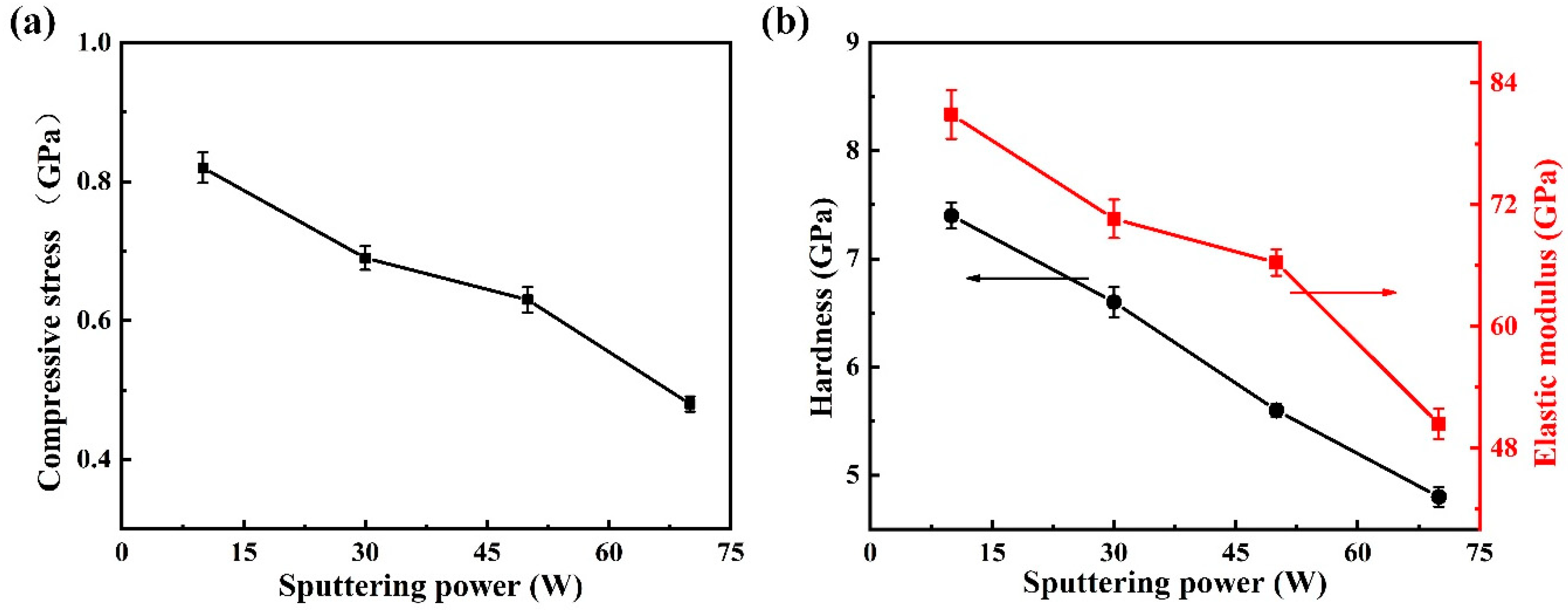

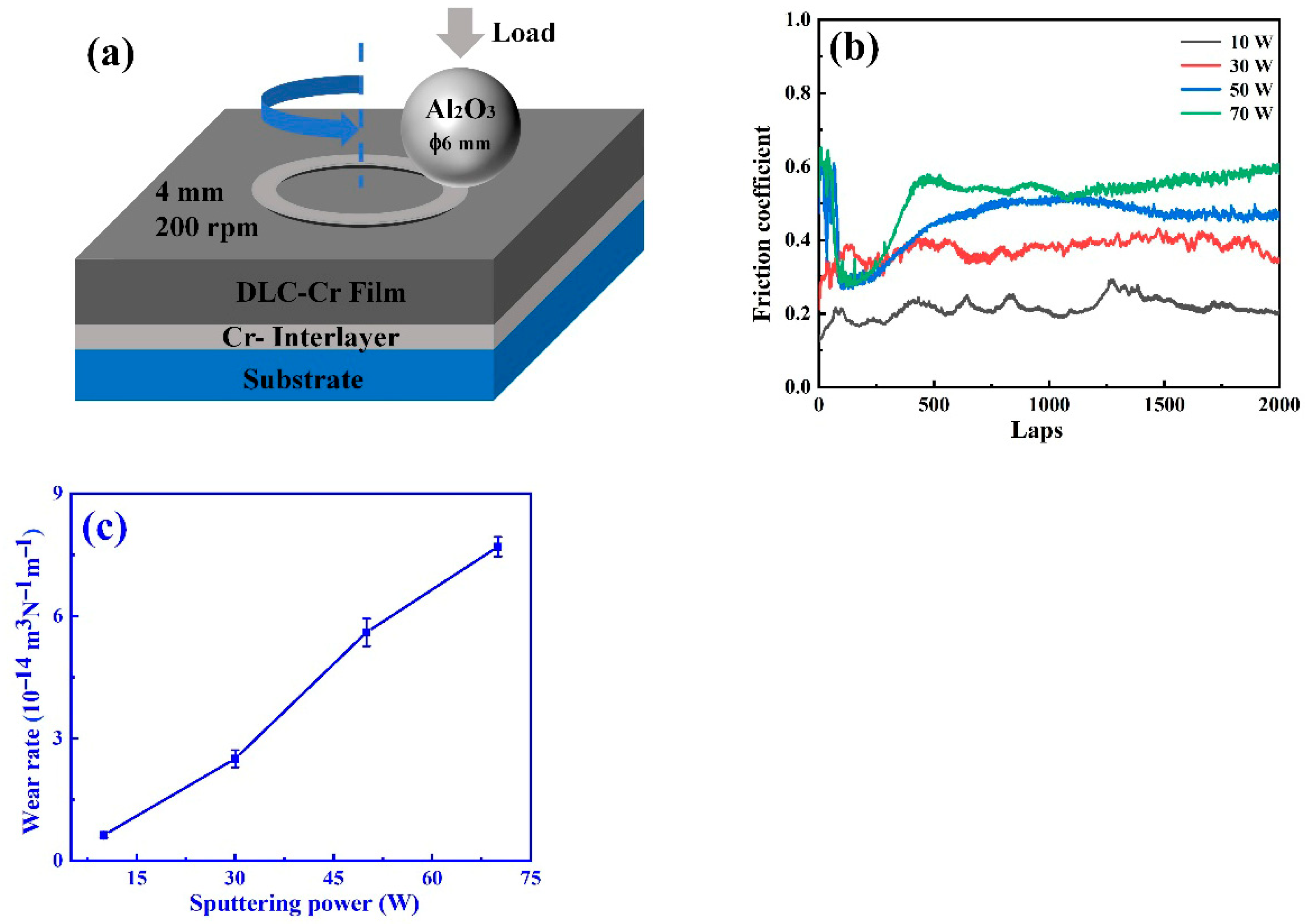

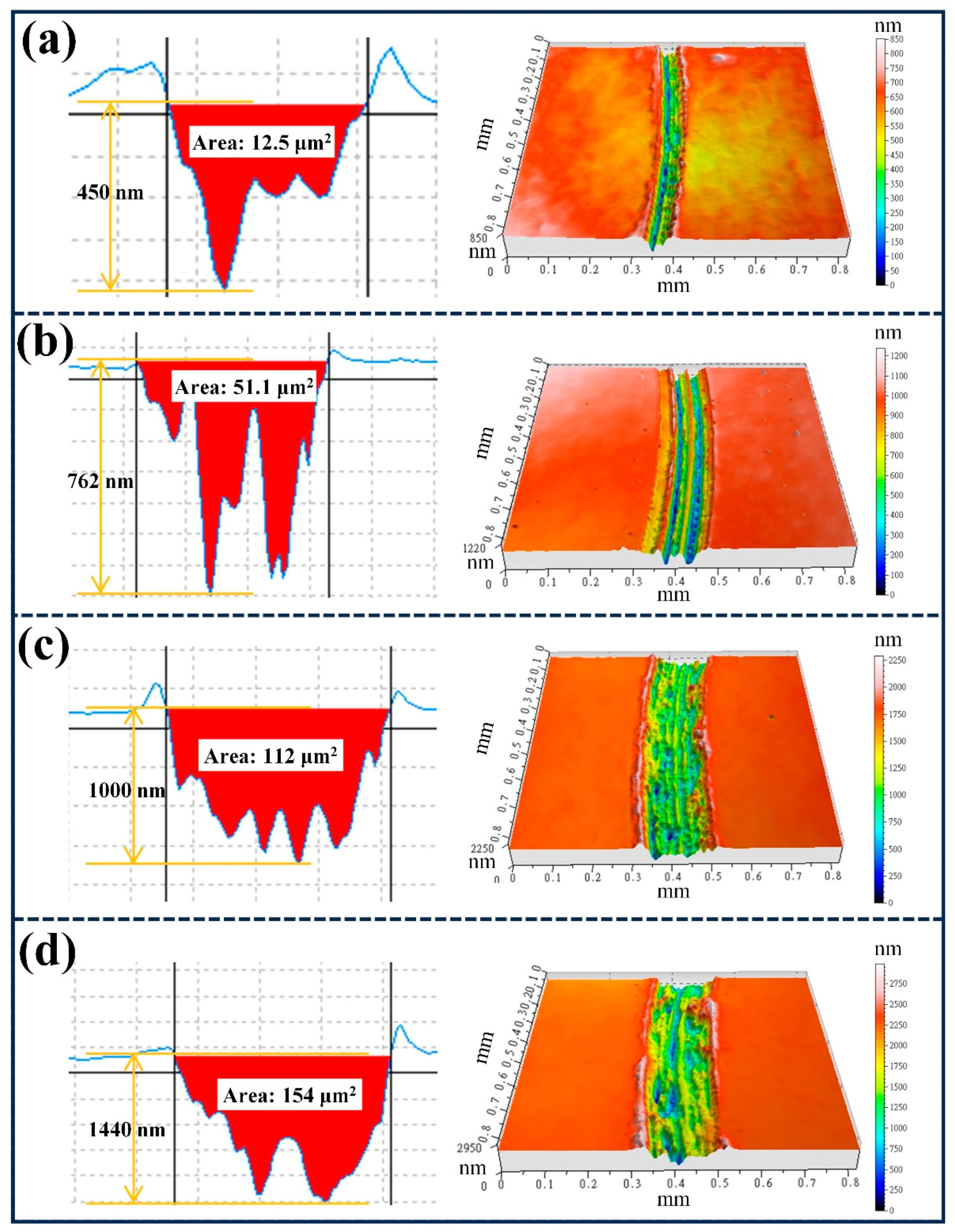

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jing, P.P.; Ma, D.L.; Gong, Y.L.; Luo, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, Y.J.; Leng, Y.X. Influence of Ag doping on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and adhesion stability of diamond-like carbon films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.C.; Dai, W.; Zhang, T.F.; Zhao, P.; Yun, J.M.; Kim, K.H.; Wang, Q.M. Microstructure and properties of Nb-doped diamond-like carbon films deposited by high power impulse magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films 2018, 663, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.M.; Horibata, S.; Miyauchi, Y.; Choi, J. Tribochemical investigation of Cr- doped diamond-like carbon with a MoDTC-containing engine oil under boundary lubricated condition. Tribol. Int. 2023, 188, 108849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, P.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B. The effects of Ti content on the wear and corrosion resistance of Ti-doped DLC films deposited on AZ91 surface via magnetron sputtering. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 43346–43360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molak, R.; Topolski, K.; Spychalski, M.; Dulinska-Molak, I.; Moronczyk, B.; Pakieła, Z.; Nieużyła, L.; Mazurkiewicz, M.; Wojucki, M.; Gebeshuber, A.; et al. Functional properties of the novel hybrid coatings combined of the oxide and DLC layer as a protective coating for AZ91E magnesium alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 380, 125040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Peng, J.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Qiu, X. Diamond-like carbon coatings in the biomedical field: Properties, applications and future development. Coatings 2021, 12, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.; Martins, J.; Carvalho, O.; Sobral, L.; Carvalho, S.; Silva, F. Tribological solutions for engine piston ring surfaces: An overview on the materials and manufacturing. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2020, 35, 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, W.; Chen, R.; Xie, B.; Wang, A. Carrier transport behavior and piezoresistive mechanism of Cr-DLC nanocomposite films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 691, 162663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Li, K.Y. Improved wear resistance at high contact stresses of hydrogen-free diamond-like carbon coatings by carbon/carbon multilayer architecture. Appl. Suff. Sci. 2019, 447, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, F.; Ehteshamzadeh, M.; Amin, M.H.; Barlow, A.J. A comparative study of surface morphology, mechanical and tribological properties of DLC films deposited on Cr and Ni nanolayers. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 5077–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tao, X.; Zhang, X.; Tian, F.; Huang, Z.; Tian, W.; Chen, J. The influences from CrN transition layer thickness to the tribological and corrosion performance of DLC films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 155, 112358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Su, F.; Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. Microstructure and tribological properties of DLC films with varying Ti interlayer thicknesses on HNBR substrate deposited by PVD. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 513, 132515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, K. Effect of hydrogenation or not of DLC on its tribological properties in vapor and liquid methanol. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 154, 112218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiariol, T.S.; Martins, G.; Hurtado, C.; Tada, D.; Corat, E.; Airoldi, V.T. Effect of individual and multiple incorporation of Ag and TiO2 on the properties of DLC films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 154, 112119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Mei, H.; Ding, J.C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.F.; Kang, H.K.; Zheng, J. Microstructure and properties of Mo doped DLC nanocomposite films deposited by a hybrid sputtering system. Vacuum 2023, 208, 111732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, V.H.T.; Rodriguez, G.C.M.; Sanchez, M.B.; Olvera, F.M.; Diaz, L.A.C.; Martinez, C.F.; Carmona, J.M.G. Effect of nitrogen doping on the mechanical and tribological properties of hydrogen-free DLC coatings deposited by arc-PVD at an industrial scale. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 499, 131825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Shang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, H.; Mei, H.; Zhao, D.; Liu, X.; Ding, J.; Zheng, J. Influence of Si content on the microstructure and properties of hydrogenated amorphous carbon films deposited by magnetron sputtering technique. Coatings 2025, 15, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Sun, W.C.; Dong, Y.R.; Ma, M.; Liu, Y.W.; Tian, S.S.; Xiao, Y.; Jia, Y.P. Electrodeposition and microstructure of Ni and B co-doped diamond-like carbon (Ni/B-DLC) films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Wan, Z.X.; Ding, J.C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.M.; Kim, K.H. Microstructure and high-temperature tribological properties of Si-doped hydrogenated diamond-like carbon films. Appl. Suff. Sci. 2018, 435, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Lu, Z.; Ding, J.C.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zheng, J. Influence of Ar/C2H2 flow ratio on the microstructure and properties of Cr-containing DLC films deposited by medium frequency magnetron sputtering. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Microstructure and high-temperature tribological properties of Ti/Si co-doped diamond-like carbon films fabricated by twin-targets reactive HiPIMS. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 141, 110573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaristo, M.; Fernandes, F.; Cavaleiro, A. Influence of the alloying elements on the tribological performance of DLC coatings in different sliding conditions. Wear 2023, 526–527, 204880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cai, L.; Huang, W.; Zhang, T.; Yu, W.; Zhang, P.; Hu, R.; Gong, X. Improvement the tribological properties of diamond-like carbon film via Mo doping in diesel condition. Vacuum 2022, 198, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, L.; Maity, S.R.; Kumar, S. Comprehensive structural, nanomechanical and tribological evaluation of silver doped DLC thin film coating with chromium interlayer (ag-DLC/Cr) for biomedical application. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 22805–22818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestra, R.M.; Castro, A.M.G.; Evaristo, M.; Escudeiro, A.; Mutafov, P.; Polcar, T.; Cavaleiro, A. Carbon-based coatings doped by copper: Tribological and mechanical behavior in olive oil lubrication. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, S79–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.C.; Mei, H.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Q.M.; Kang, M.C.; Zhang, T.F.; Kim, K.H. Microstructure and wettability of novel Al containing diamond-like carbon films deposited by a hybrid sputtering system. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 868, 159130–159138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.C.; Chen, M.; Mei, H.; Jeong, S.; Zheng, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Kim, K.H. Microstructure; mechanical, and wettability properties of Al-doped diamond-like films deposited using a hybrid deposition technique: Bias voltage effects. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 123, 108861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xiao, L.R.J.; Zhang, X.; Mo, X.; Jiang, A. Cr content regulates the friction and corrosion resistance of Cr/F-DLC thin films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 157, 112482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, Y.; Shi, B.; Hu, E.; Hei, H. Investigation of hydrophobic and anti-corrosive behavior of Cr-DLC film on stainless steel bipolar plate. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 129, 109352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarakinos, K.; Alami, J.; Konstantinidis, S. High power pulsed magnetron sputtering: A review on scientific and engineering state of the art. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 204, 1661–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, S.; Ashtijoo, P.; Odeshi, A.; Yang, Q.Q. Evaluation of Stoney equation for determining the internal stress of DLC thin films using an optical profiler. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 308, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, B.J.; Schiller, T.L.; Proprentner, D.; Walker, M.; Low, C.T.J.; Shollock, B.; Sun, H.; Navabpour, P. Effect of chromium doping on high temperature tribological properties of silicon-doped diamond-like carbon films. Tribol. Int. 2020, 152, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chai, L.; Wang, P.; Li, Y. Effect of power on the microstructure and frictional properties of Si-DLC films prepared by high-power impulse magnetron sputtering (HiPIMS). Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 513, 132513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, J.; Wan, Y.; Pu, J. Corrosion and tribocorrosion behavior of W doped DLC coating in artificial seawater. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 109, 108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Shi, L.; Wang, P.; Xia, Y.; Liu, W. Influence of methane flow on the microstructure and properties of TiAl-doped a-C:H films deposited by middle frequency reactive magnetron sputtering. Surf. Interface Anal. 2009, 41, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J. Diamond-like amorphous carbon. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2002, 37, 129–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greczynski, G.; Primetzhofer, D.; Hultman, L. Reference binding energies of transition metal carbides by core-level x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy free from Ar+ etching artefacts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 436, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Shang, J.; Zhuang, W.; Ding, J.C.; Mei, H.; Yang, Y.; Ran, S. Structural and tribomechanical properties of Cr-DLC films deposited by reactive high power impulse magnetron sputtering. Vacuum 2024, 230, 113611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://srdata.nist.gov/xps/EnergyTypeElement (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Neumann, A. Contact angles and their temperature dependence: Thermodynamic status, measurement, interpretation and application. Adv. Colloid Interf. Sci. 1974, 4, 105–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.L.; Guo, P.; Li, X.W.; Wang, A.Y. Comparative study on structure and wetting properties of diamond-like carbon films by W and Cu doping. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2017, 73, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J.A.; Martinez, I.F.; Lopez, J.C.S.; Rojas, T.C.; Wennberg, A.; Gonzalez, V.B.; Aldareguia, J.M.M.; Monclus, M.A.; Arrabal, R.G. Tribomechanical properties of hard Cr-doped DLC coatings deposited by low-frequency HiPIMS. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 382, 124899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.Q.; Li, H.Q.; Peng, Y.L.; Dai, M.J.; Lin, S.S.; Shi, Q.; Wei, C.B. Residual stress and tribological behavior of hydrogen-free Al-DLC films prepared by HiPIMS under different bias voltages. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 445, 128713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Lee, W.Y.; Tokoroyama, T.; Murashima, M.; Umehara, N. Tribo-chemical wear of various 3d-transition metals against DLC: Influence of tribo-oxidation and low- shear transferred layer. Tribol. Int. 2023, 177, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ding, J.; Zhuang, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Mei, H.; Zhao, D.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J. Tailoring the Microstructure and Properties of HiPIMS-Deposited DLC-Cr Nanocomposite Films via Chromium Doping. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020150

Ding J, Zhuang W, Wang Q, Wang Q, Mei H, Zhao D, Liu X, Zheng J. Tailoring the Microstructure and Properties of HiPIMS-Deposited DLC-Cr Nanocomposite Films via Chromium Doping. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020150

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Jicheng, Wenjian Zhuang, Qingye Wang, Qi Wang, Haijuan Mei, Dongcai Zhao, Xingguang Liu, and Jun Zheng. 2026. "Tailoring the Microstructure and Properties of HiPIMS-Deposited DLC-Cr Nanocomposite Films via Chromium Doping" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020150

APA StyleDing, J., Zhuang, W., Wang, Q., Wang, Q., Mei, H., Zhao, D., Liu, X., & Zheng, J. (2026). Tailoring the Microstructure and Properties of HiPIMS-Deposited DLC-Cr Nanocomposite Films via Chromium Doping. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020150