Evidence of sp-d Exchange Interactions in CdSe Nanocrystals Doped with Mn, Fe and Co: Atomistic Tight-Binding Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Details

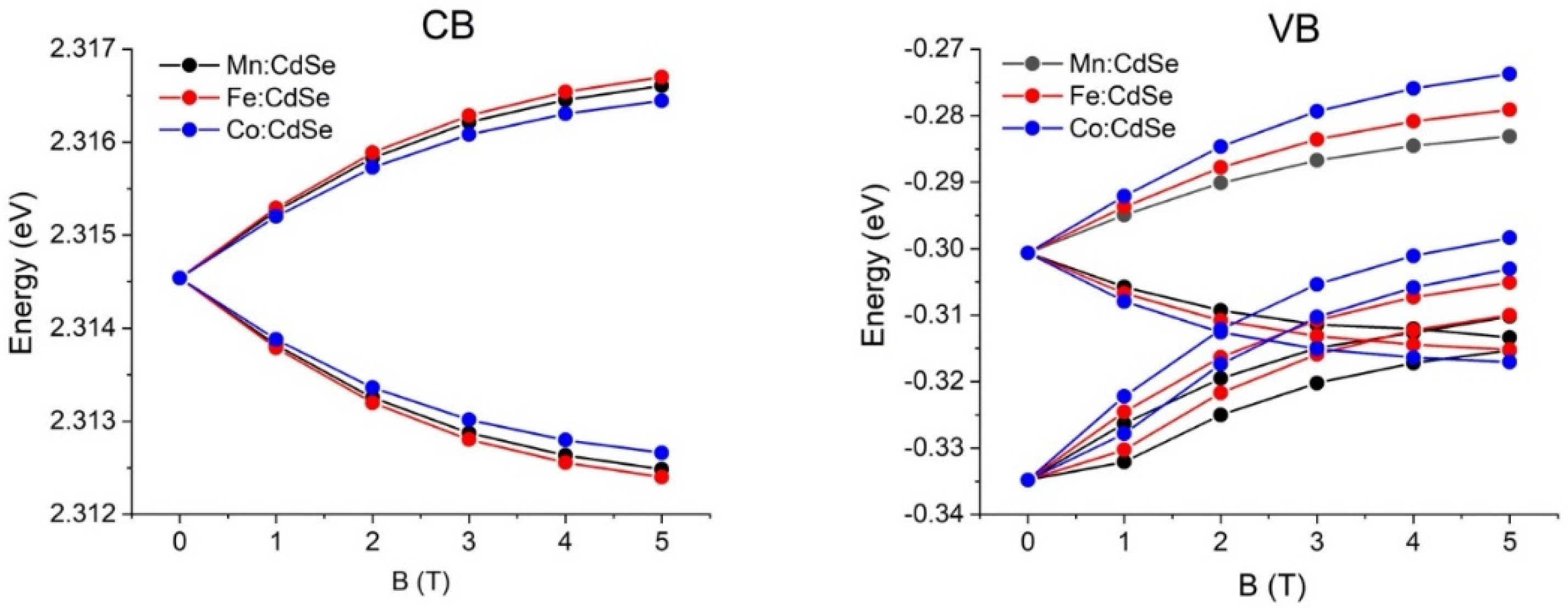

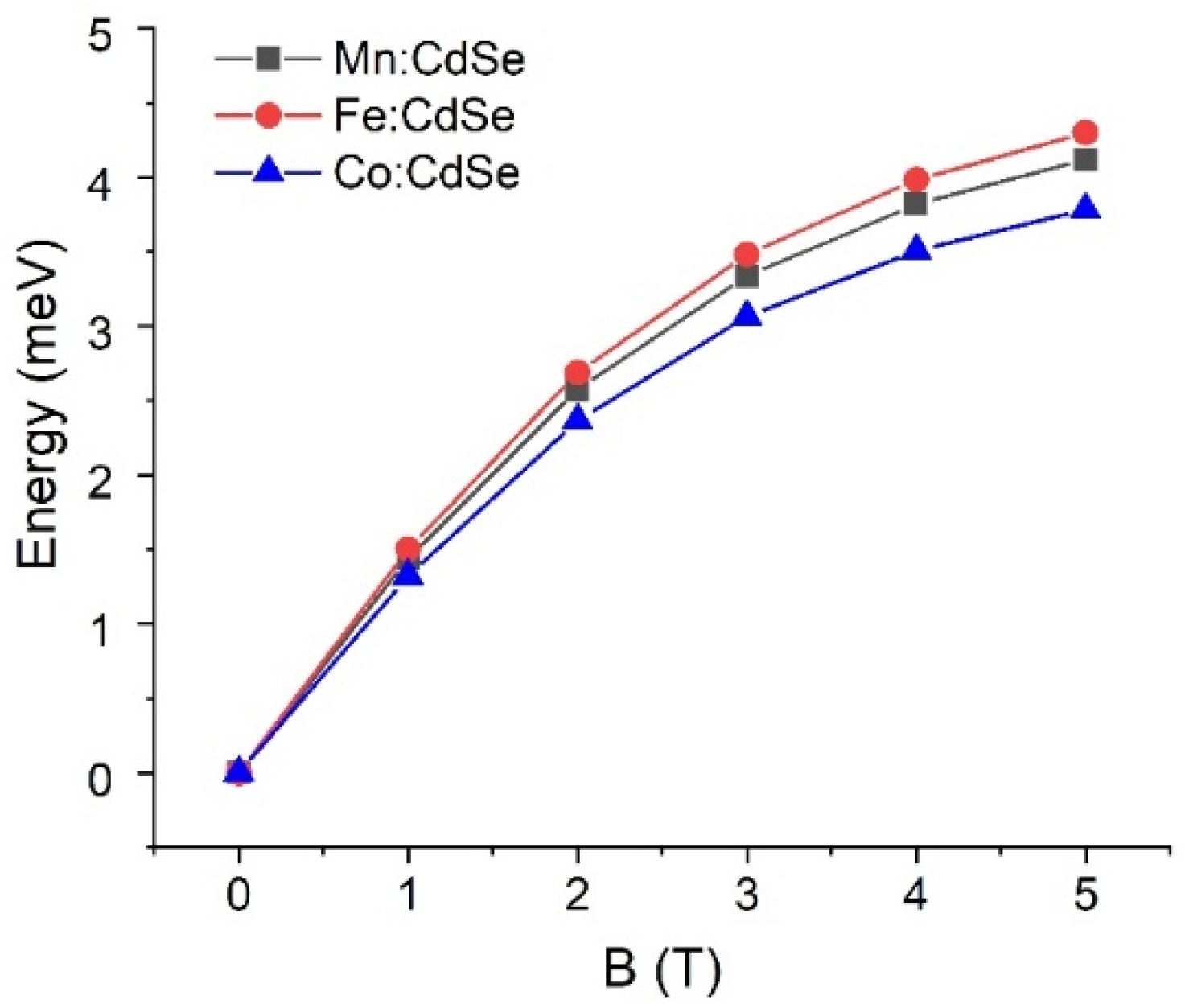

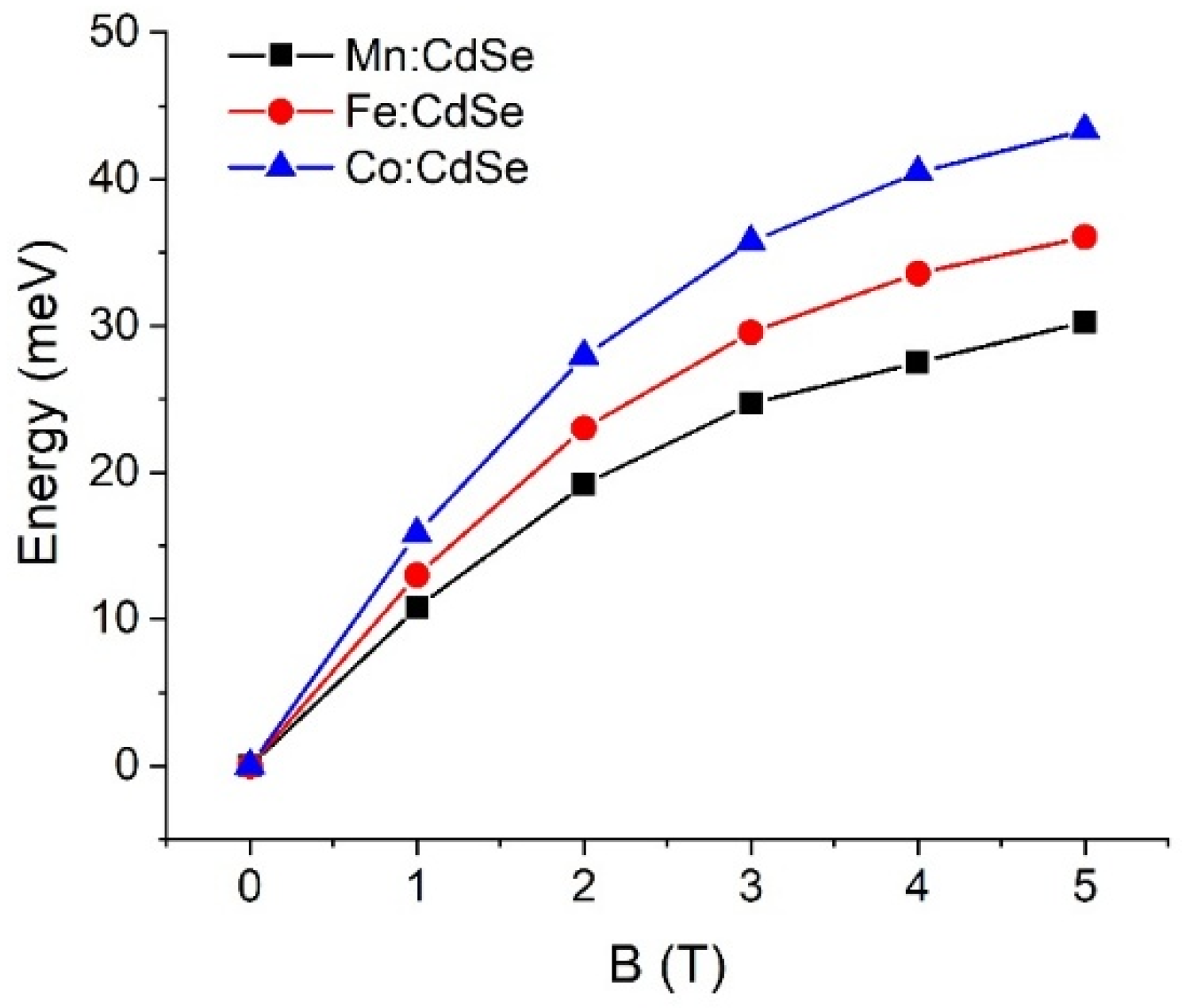

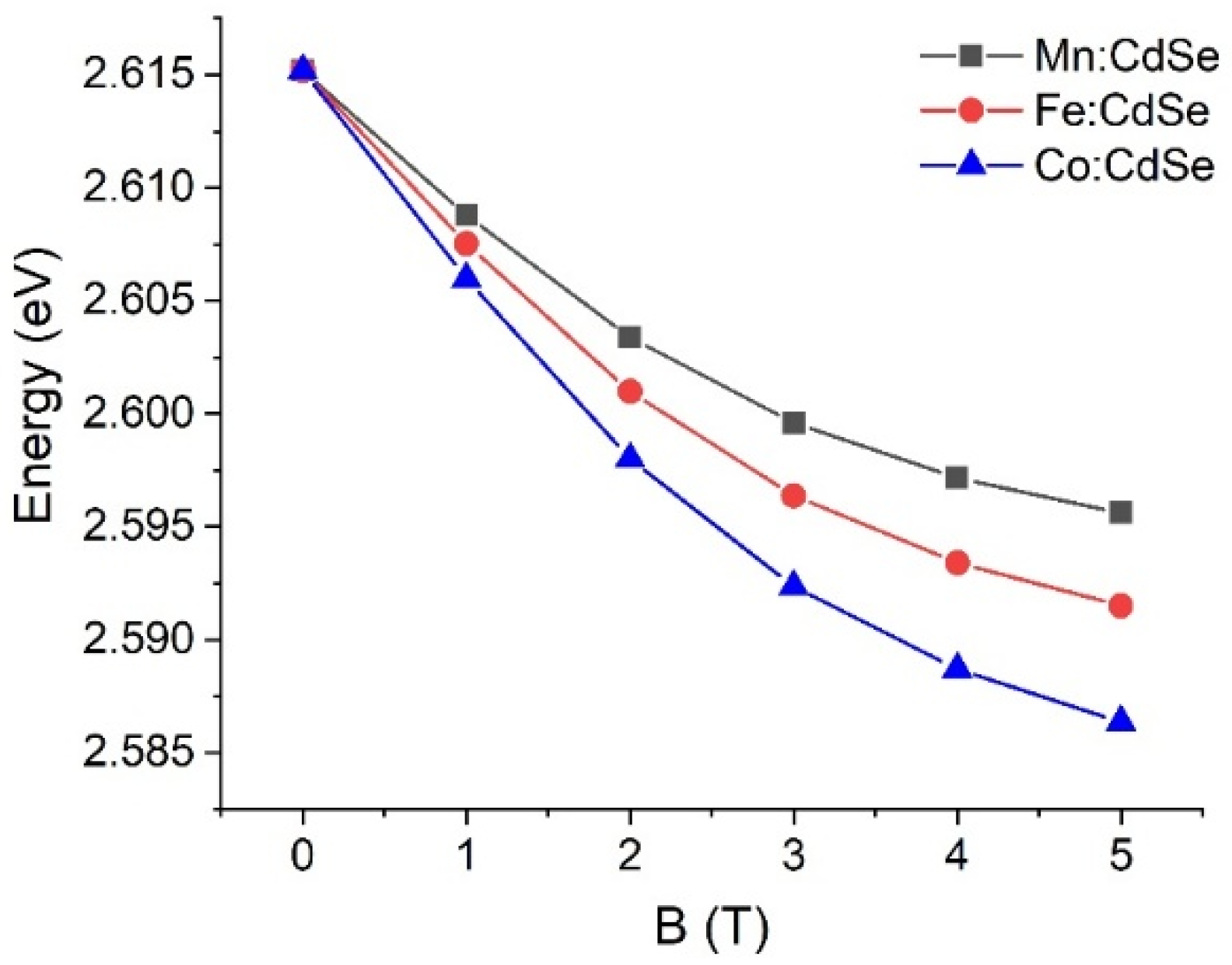

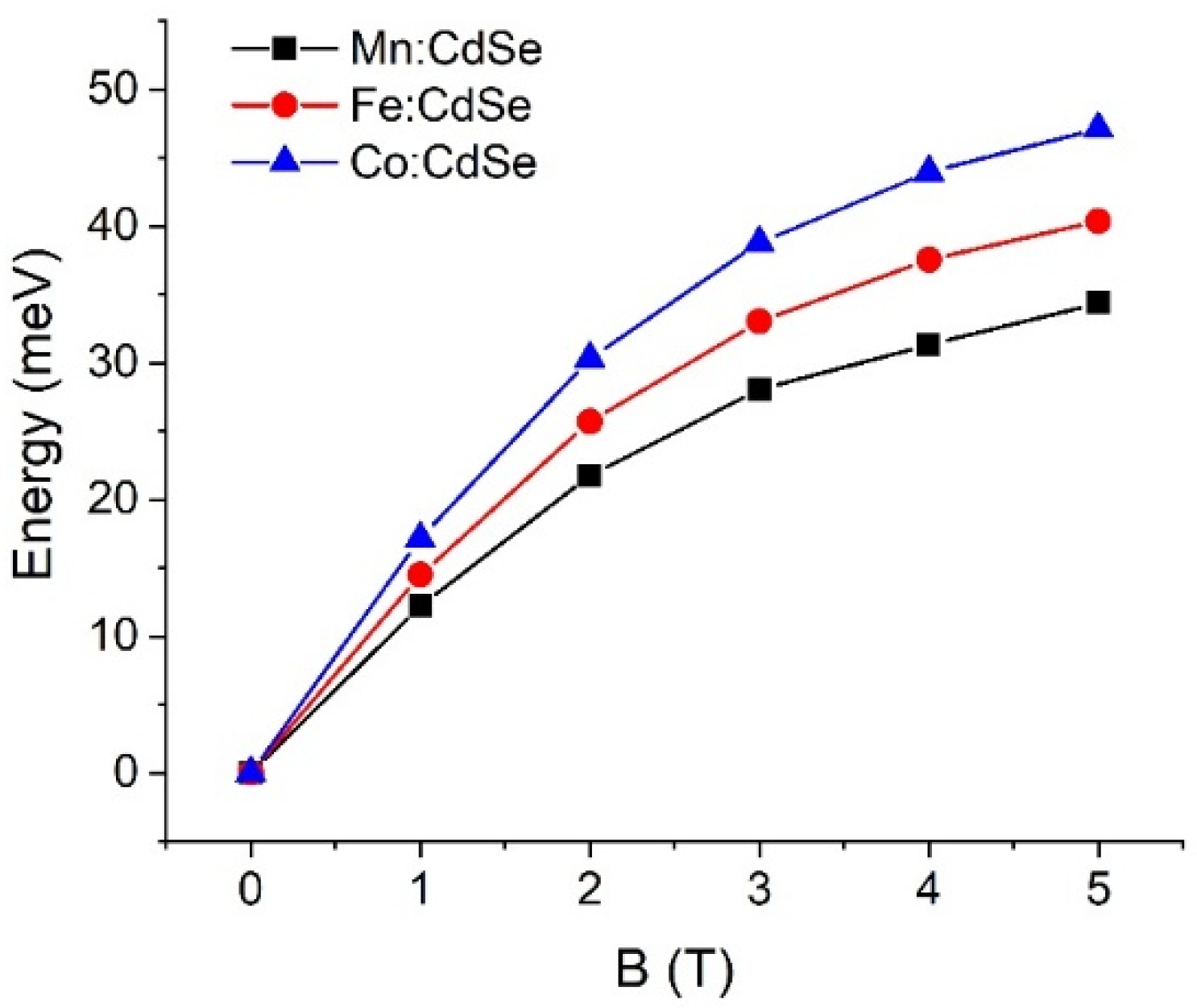

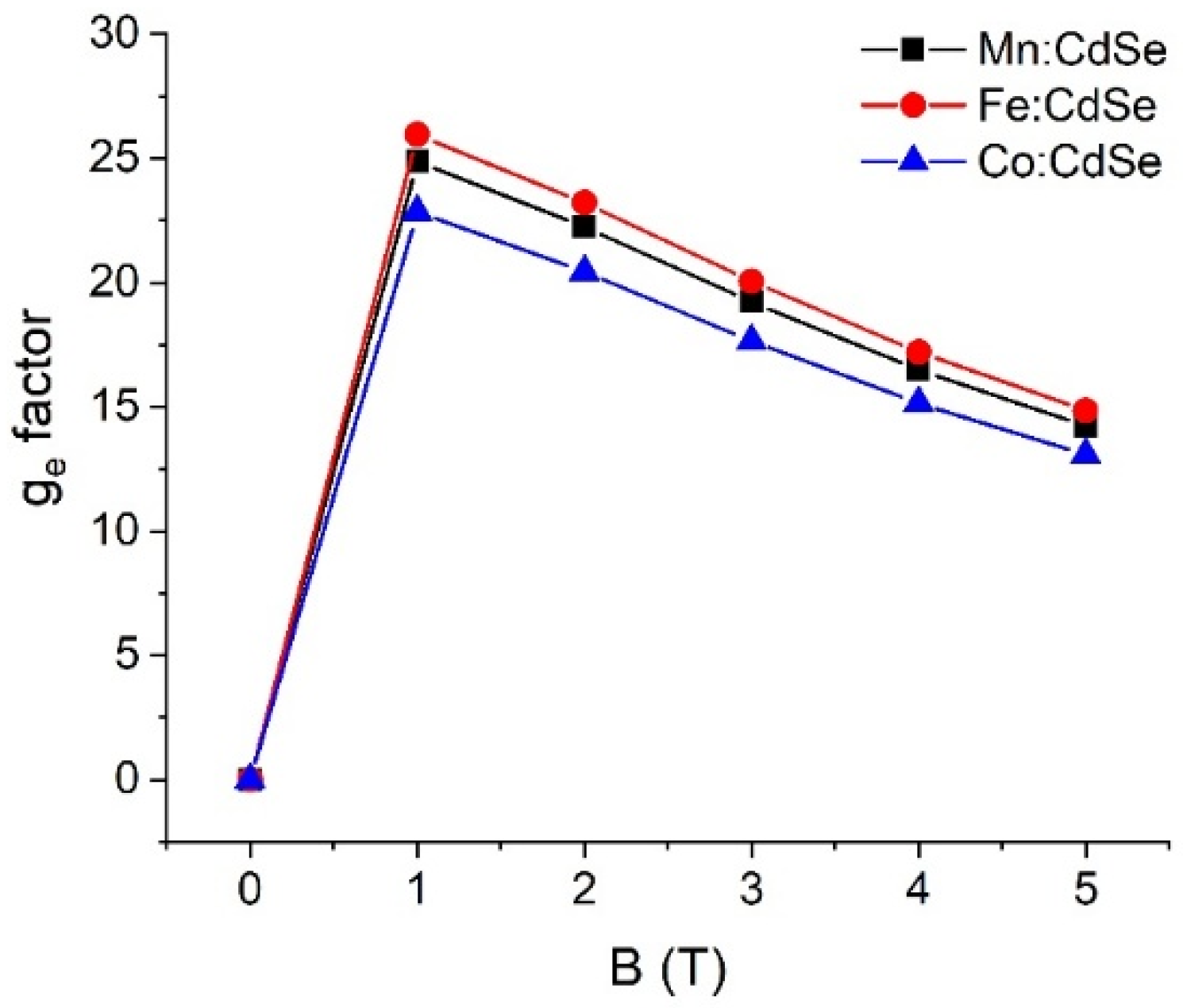

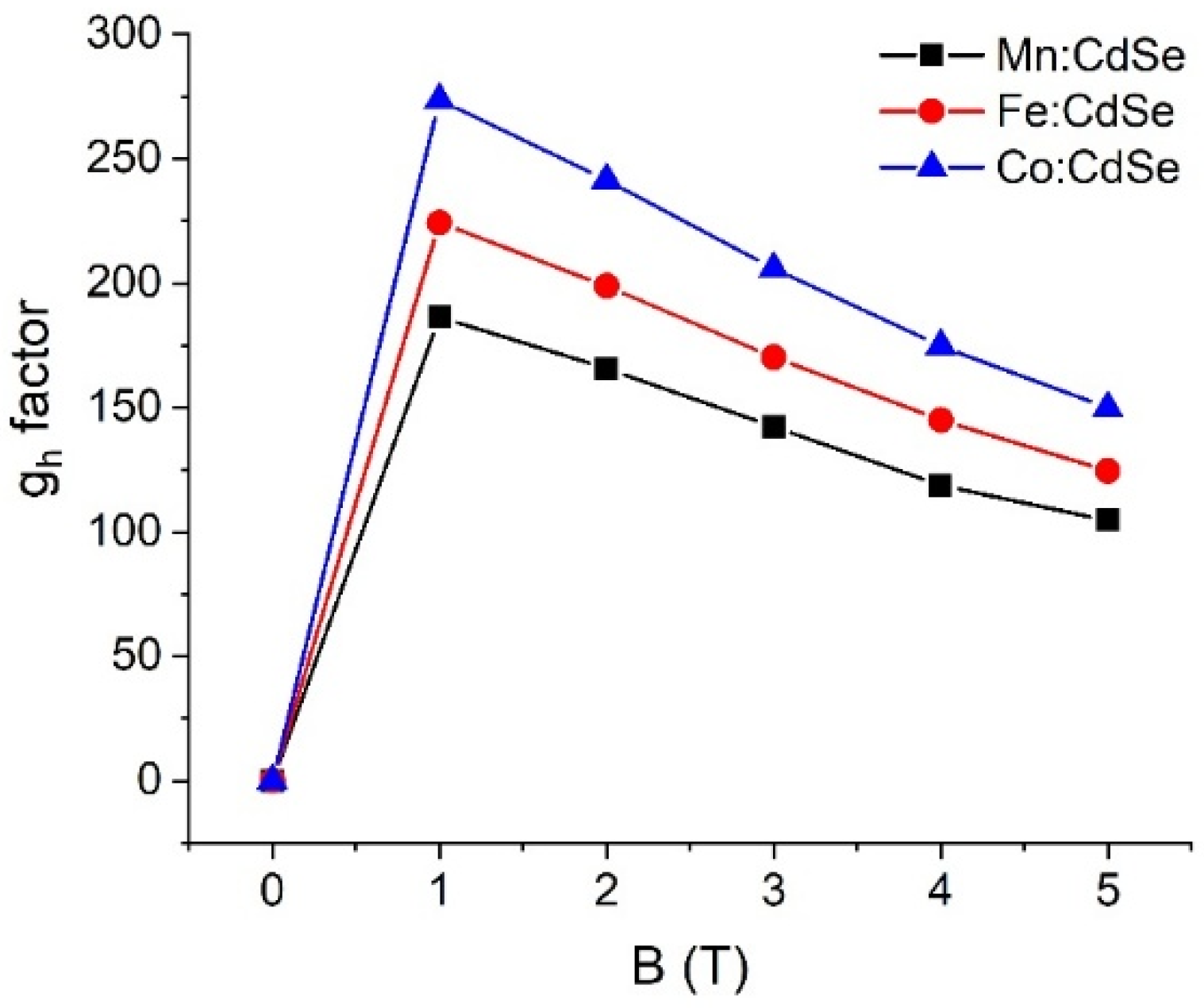

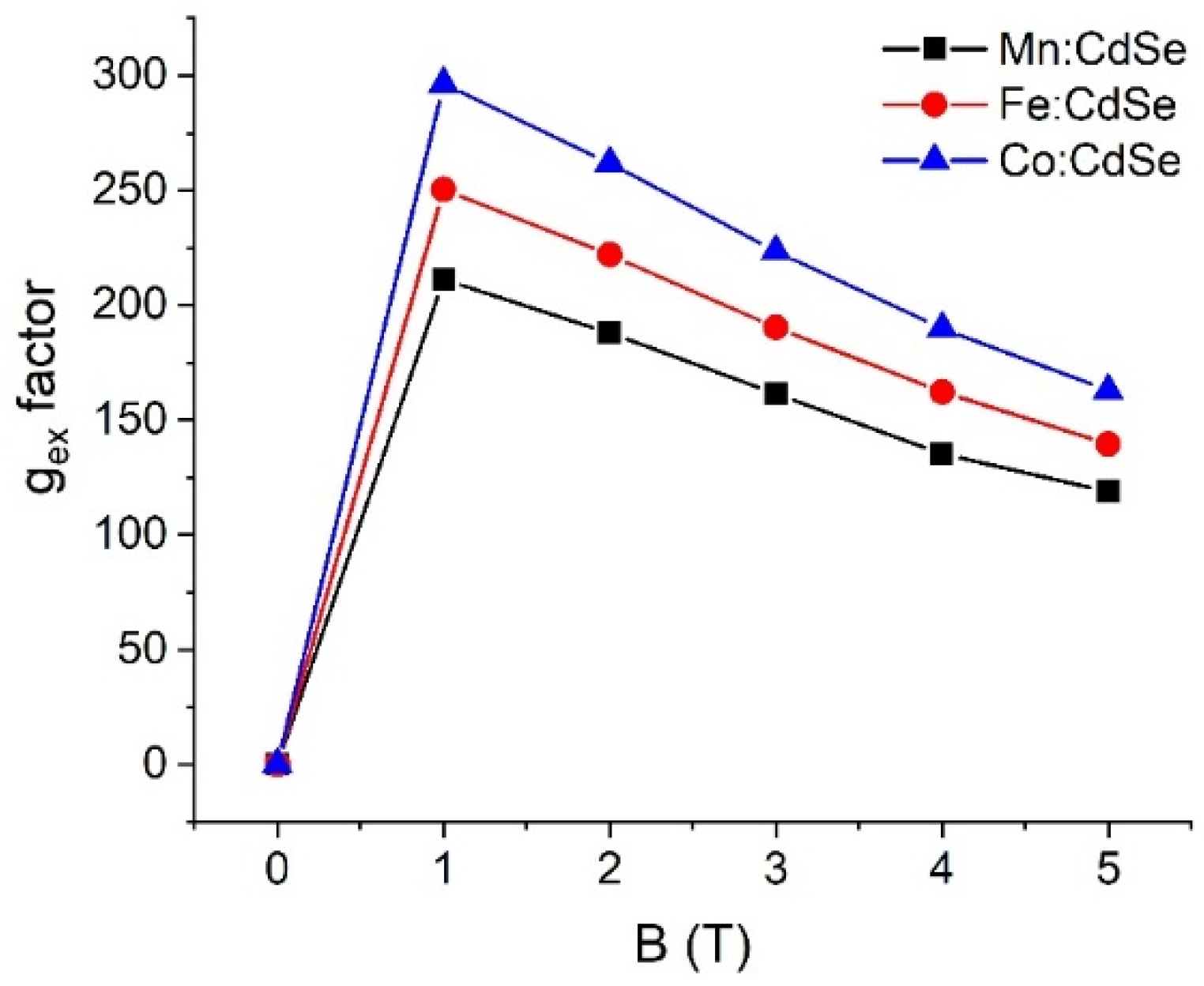

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Efros, A.L.; Rashba, E.I.; Rosen, M. Paramagnetic ion-doped nanocrystal as a voltage-controlled spin filter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 206601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulac, R.; Archer, P.I.; Ochsenbein, S.T.; Gamelin, D.R. Mn2+-doped CdSe quantum dots: New inorganic materials for spin-electronics and spin-photonics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 3873–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzer, F.; Barrows, C.J.; Graf, A.; Schmitz, A.; Erickson, C.S.; Gamelin, D.R.; Bacher, G. Current-induced magnetic polarons in a colloidal quantum-dot device. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 4768–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, F.; Fielding, A.J.; Turyanska, L.; Patanè, A. Realization of Universal Quantum Gates with Spin-Qudits in Colloidal Quantum Dots. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2019, 2, 1900017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furdyna, J.K. Diluted magnetic semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 1988, 64, R29–R64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furdyna, J.K. Diluted magnetic semiconductors: An interface of semiconductor physics and magnetism. J. Appl. Phys. 1982, 53, 7637–7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyosaki, H.; Fukumura, T.; Yamada, Y.; Nakajima, K.; Chikyow, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Koinuma, H.; Kawasaki, M. Anomalous Hall effect governed by electron doping in a room-temperature transparent ferromagnetic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Liu, X.; Kweon, K.E.; Joo, J.; Park, J.; Ko, K.-T.; Lee, D.W.; Shen, S.; Tivakornsasithorn, K.; Son, J.S.; et al. Giant Zeeman splitting in nucleation-controlled doped CdSe: Mn2+ quantum nanoribbons. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhira, T.; Uchida, K.; Matsuda, Y.H.; Miura, N.; Twardowski, A. Giant Faraday rotation spectra of Zn 1− x Mn x Se observed in high magnetic fields up to 150 T. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhira, T.; Uchida, K.; Matsuda, Y.H.; Miura, N.; Twardowski, A. Magnetic and non-magnetic Faraday rotation in ZnMnSe in high magnetic fields. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 1999, 14, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, D.U.; Furdyna, J.K.; Ramdas, A.K. Interband Faraday rotation in diluted magnetic semiconductors: Zn 1− x Mn x Te and Cd 1− x Mn x Te. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 34, 6943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulac, R.; Archer, P.I.; Liu, X.; Lee, S.; Salley, G.M.; Dobrowolska, M.; Furdyna, J.K.; Gamelin, D.R. Spin-polarizable excitonic luminescence in colloidal Mn2+-doped CdSe quantum dots. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 1197–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.H.; Nurmikko, A.V. Formation of the bound magnetic polaron in (Cd, Mn) Se. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 51, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkulov, I.A.; Yakovlev, D.R.; Kavokin, K.V.; Mackh, G.; Ossau, W.; Waag, A.; Landwehr, G. Hierarchy of relaxation times in the formation of an excitonic magnetic polaron in (CdMn) Te. JETP Lett 1995, 62, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulac, R.; Schneider, L.; Archer, P.I.; Bacher, G.; Gamelin, D.R. Light-induced spontaneous magnetization in doped colloidal quantum dots. Science 2009, 325, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, I.R.; Oszwałdowski, R.; Whiteside, V.R.; Eginligil, M.; Petrou, A.; Zutic, I.; Chou, W.-C.; Fan, W.C.; Petukhov, A.G.; Kim, S.J.; et al. Robust magnetic polarons in type-II (Zn, Mn) Te/ZnSe magnetic quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2010, 82, 195320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkabot, W. Atomistic tight-binding investigations of Mn-doped ZnSe nanocrystal: Electronic, optical and magnetic characteristics. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 140, 106401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkabot, W. Tunable electronic, optical and magnetic characteristics in Mn-doped inverted type-I ZnSe/CdSe core/shell nanocrystals: Atomistic tight-binding model. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 147, 106705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkabot, W. Observation of spin-splitting energies on sp–d exchange interactions tailored in colloidal CdSe/CdMnS core/shell nanoplatelets: An atomistic tight-binding model. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 11807–11814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, G.; Rao, B.; Jena, P.; Kawazoe, Y. Dilute magnetic III–V semiconductor spintronics materials: A first-principles approach. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2006, 36, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, H.; Bhushan, M.; Singh, L.R. A comprehensive review on theoretical concepts, types and applications of magnetic semiconductors. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 288, 116201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama-Yoshida, H.; Sato, K.; Fukushima, T.; Toyoda, M.; Kizaki, H.; Dinh, V.A.; Dederichs, P.H. Theory of ferromagnetic semiconductors. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2007, 204, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietl, T.; Ohno, H. Dilute ferromagnetic semiconductors: Physics and spintronic structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014, 86, 187–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelikowsky, J.R.; Kaxiras, E.; Wentzcovitch, R.M. Theory of spintronic materials. Phys. Status Solidi (B) 2006, 243, 2133–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žutić, I.; Fabian, J.; Das Sarma, S. Spintronics: Fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2004, 76, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, B.; Kamat, P.V. CdSe quantum dot sensitized solar cells. Shuttling electrons through stacked carbon nanocups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11124–11131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe-Sullivan, S.; Woo, W.-K.; Steckel, J.S.; Bawendi, M.; Bulović, V. Tuning the performance of hybrid organic/inorganic quantum dot light-emitting devices. Org. Electron. 2003, 4, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I.-F.; Yeh, C.-S. Synthesis of Gd doped CdSe nanoparticles for potential optical and MR imaging applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 2079–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, W.-C.; Sung, Y.-M.; Kim, T.G.; Chae, W.-S. Synthesis of Mn-doped zinc blende CdSe nanocrystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 173111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamizi, N.A.; Aplop, F.; Haw, H.Y.; Sabri, A.N.; Wern, A.Y.Y.; Shapril, N.N.; Johan, M.R. Tunable optical properties of Mn-doped CdSe quantum dots synthesized via inverse micelle technique. Opt. Mater. Express 2016, 6, 2915–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshchenko, V.; Dahnovsky, Y. Magnetic effects in Mn-doped CdSe nanocrystals. Phys. Status Solidi (B) 2015, 252, 2275–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S.K.; Dubal, D.P.; Ghodake, G.S.; Fulari, V.J. Electronic impurities (Fe, Mn) doping in CdSe nanostructures for improvements in photoelectrochemical applications. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 33184–33189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindra, J.K.; Kurian, G.; Christian, J.H.; Van Tol, J.; Singh, K.; Dalal, N.S.; Mochena, M.D.; Stoian, S.A.; Strouse, G.F. Evidence of ferrimagnetism in Fe-doped CdSe quantum dots. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 8446–8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Dutta, A.; Banerjee, S.; Sinha, T. Phonon modes and activation energy of Fe-doped CdSe nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2014, 18, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Banerjee, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Sinha, T.P. Magnetic and dielectric study of Fe-doped CdSe nanoparticles. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2018, 14, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Verma, N.K. Synthesis and characterization of Fe-doped CdSe nanoparticles as dilute magnetic semiconductor. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2012, 25, 2425–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridevi, D.; Sundaravadivel, E.; Kanagaraj, P. Influence of Fe doping on structural, physicochemical and biological properties of CdSe nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2019, 101, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.N.; Bindra, J.K.; Jakhar, N.; Singh, K. Switching-on superparamagnetism in diluted magnetic Fe (III) doped CdSe quantum dots. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 1738–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimpf, A.M.; Gamelin, D.R. Thermal tuning and inversion of excitonic Zeeman splittings in colloidal doped CdSe quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 1264–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Xu, J.; Chen, H. Enhanced anodic electrochemiluminescence from Co2+-doped CdSe nanocrystals for alkaline phosphatase assay. Electroanalysis 2013, 25, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.T.; Su, D.; van Buuren, T.; Meulenberg, R.W. Electronic structure of cobalt doped CdSe quantum dots using soft X-ray spectroscopy. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 8313–8321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Verma, N.K. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of cobalt-doped CdSe nanoparticles. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2014, 37, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Münzer, F.; Choi, B.K.; Lorenz, S.; Kim, I.Y.; Ackermann, J.; Chang, H.; Czerney, T.; Kale, V.S.; Hwang, S.-J.; et al. Co2+-doping of magic-sized CdSe clusters: Structural insights via ligand field transitions. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 7350–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furdyna, J.K. Diluted magnetic semiconductors: Issues and opportunities. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 1986, 4, 2002–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkusinski, M.; Voznyy, O.; Hawrylak, P. Fine structure and size dependence of exciton and biexciton optical spectra in CdSe nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2010, 82, 245304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadi, D.J. Spin-orbit splitting in crystalline and compositionally disordered semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 1977, 16, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippens, P.E.; Lannoo, M. Calculation of the band gap for small CdS and ZnS crystallites. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 39, 10935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, W.A. Elementary Electronic Structure (Revised Edition); World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Madelung, O. Numerical Data and Functional Relationships in Science and Technology; Landolt-Bomstein, New Series, Group III; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Oyafuso, F.; von Allmen, P.; Klimeck, G. Boundary conditions for the electronic structure of finite-extent embedded semiconductor nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 045316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaj, J.; Planel, R.; Fishman, G. Relation of magneto-optical properties of free excitons to spin alignment of Mn2+ ions in Cd1− xMnxTe. Solid State Commun. 1993, 88, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaj, J.A.; Kossut, J. Basic Consequences of sp–d and d–d Interactions in DMS. In Introduction to the Physics of Diluted Magnetic Semiconductors; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulos, A.; McCombs, J.R. PRIMME: PReconditioned Iterative MultiMethod Eigensolver—Methods and software description. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. (TOMS) 2010, 37, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Romero, E.; Stathopoulos, A. PRIMME_SVDS: A high-performance preconditioned SVD solver for accurate large-scale computations. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2017, 39, S248–S271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkabot, W. Electronic and optical properties of single substitutional Mn dopant in CdSe nanocrystals and CdSe/ZnSe core/shell nanocrystals. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2023, 138, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rederth, D.; Oszwałdowski, R.; Petukhov, A.; Pientka, J. Multiband Electronic Structure of Magnetic Quantum Dots: Numerical Studies. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.01565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

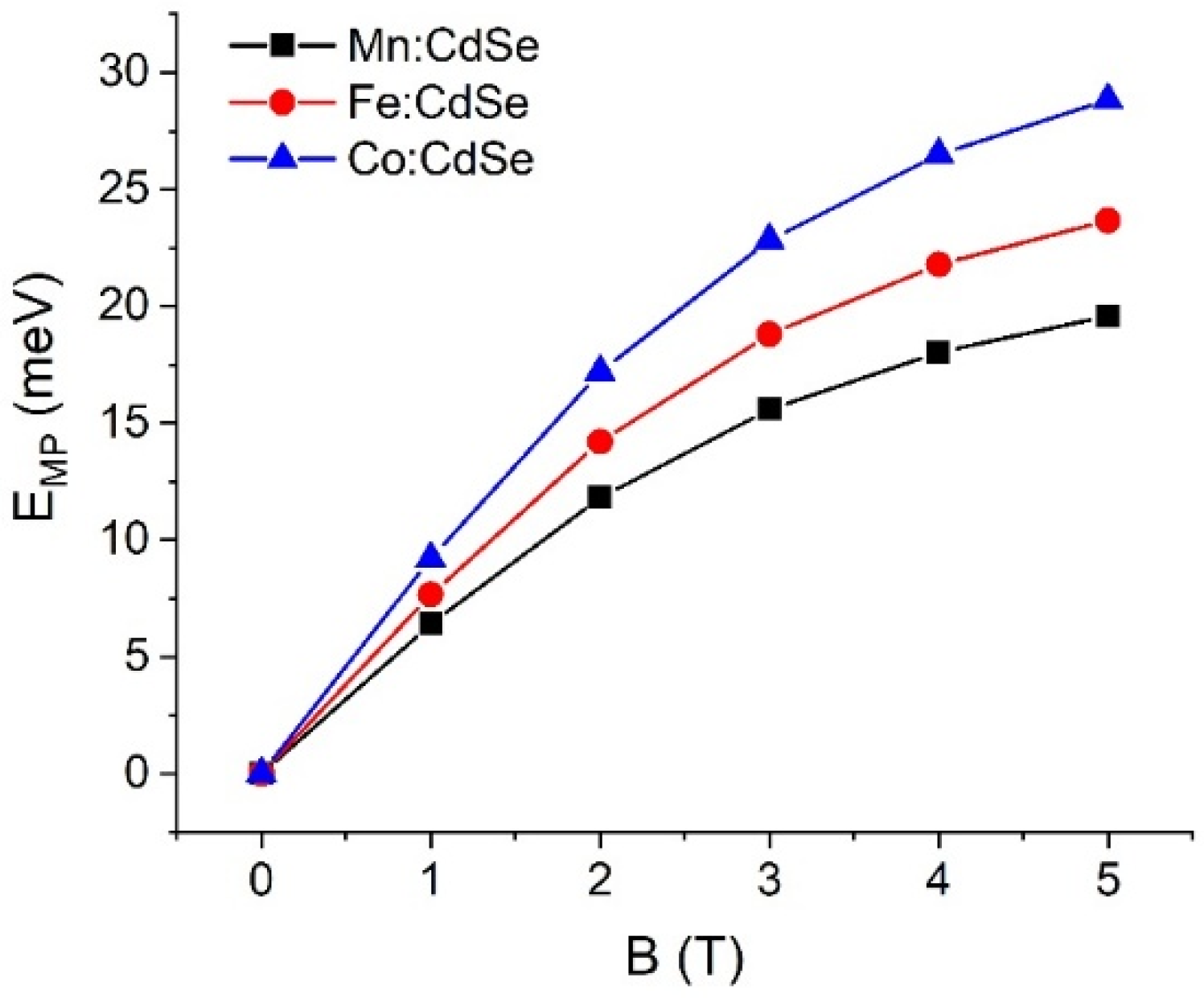

| Material | (eV) | (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| Mn:CdSe | 0.23 | −1.27 |

| Fe:CdSe | 0.26 | −1.53 |

| Co:CdSe | 0.28 | −1.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kalasuwan, P.; Sukkabot, W. Evidence of sp-d Exchange Interactions in CdSe Nanocrystals Doped with Mn, Fe and Co: Atomistic Tight-Binding Simulation. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020122

Kalasuwan P, Sukkabot W. Evidence of sp-d Exchange Interactions in CdSe Nanocrystals Doped with Mn, Fe and Co: Atomistic Tight-Binding Simulation. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020122

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalasuwan, Pruet, and Worasak Sukkabot. 2026. "Evidence of sp-d Exchange Interactions in CdSe Nanocrystals Doped with Mn, Fe and Co: Atomistic Tight-Binding Simulation" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020122

APA StyleKalasuwan, P., & Sukkabot, W. (2026). Evidence of sp-d Exchange Interactions in CdSe Nanocrystals Doped with Mn, Fe and Co: Atomistic Tight-Binding Simulation. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020122