Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets: Properties, Preparation and Applications in Thermal Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Structure and Physical Properties

2.1. Structure

2.2. Physical Properties

3. Preparation of BNNSs

3.1. Top-Down Approaches

3.1.1. Tape Exfoliation

3.1.2. Ball Milling

3.1.3. Liquid-Phase Exfoliation

3.2. Bottom-Up Approaches

3.2.1. Chemical Vapor Deposition

3.2.2. Metal–Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition

| Methods | Typical Lateral Size of BNNSs | Typical Thickness | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tape exfoliation | 10–100 μm | mono- to few- layer | highest quality, simple and low-cost | not scalable, poor dimensional control | intrinsic properties, fundamental studies, proof-of-concept devices |

| Ball milling | 50 nm–1 μm | few- to tens-of- layers | scalable, simple and low-cost | structural defects, poor dimensional control | composite fillers, heat-dissipation coatings, solid lubricants |

| Liquid-phase exfoliation | 100 nm–5 μm | mono- to few- layer | scalable, high quality, versatile | time consuming, poor dimensional control | composite fillers, heat-dissipation coatings, ink-based printing |

| CVD | mm- to wafer-scale | mono- to few- layer | large-area film, desired thickness control | high cost, transfer bottleneck, | wafer-scale electronics, dielectric layers; heterostructures |

| MOCVD | wafer-scale continuous films | few-layer to um-scale | good uniformity control, industry-compatible | high cost, grain boundaries and defects | dielectric layers, passivation layers, heterostructures |

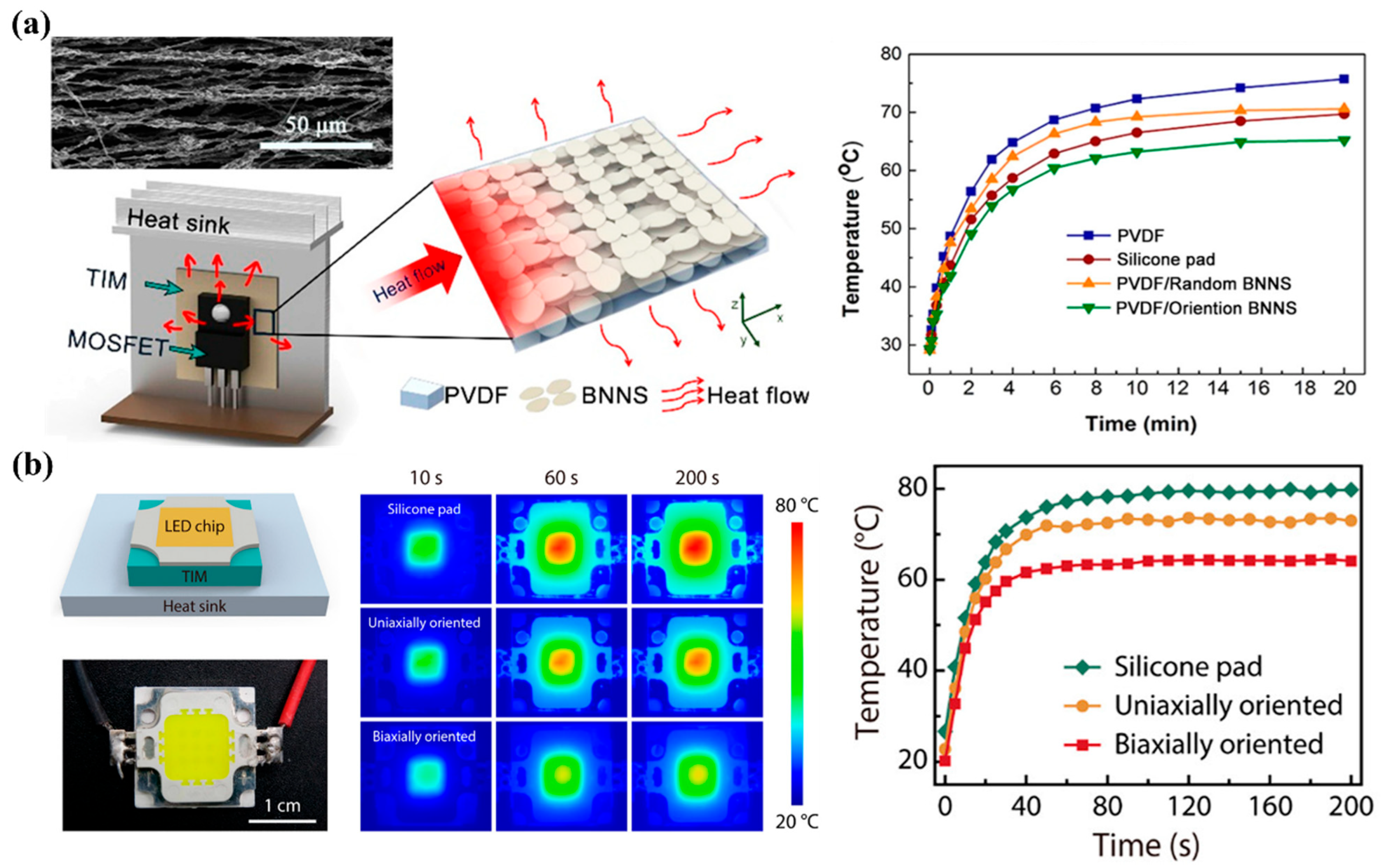

4. Applications of BNNSs in Thermal Management

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

- Scalable synthesis of large-area, high quality BNNSs.

- 2.

- Advanced alignment engineering in polymer matrices.

- 3.

- Interface engineering for BNNSs and polymer composites.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, S.; Yin, Y.; Hu, C.; Rezai, P. 3D Integrated Circuit Cooling with Microfluidics. Micromachines 2018, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.-J.; Li, G.; Yao, Y.-M.; Zeng, X.-L.; Zhu, P.-L.; Sun, R. Recent advances in polymer-based electronic packaging materials. Compos. Commun. 2020, 19, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Tian, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Z.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Hirtz, T.; Wu, R.; Gou, G.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. High Thermal Conductivity 2D Materials: From Theory and Engineering to Applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2200409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, L.; Broido, D.A. Theory of thermal transport in multilayer hexagonal boron nitride and nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 035436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Scullion, D.; Gan, W.; Falin, A.; Zhang, S.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Chen, Y.; Santos, E.J.G.; Li, L.H. High thermal conductivity of high-quality monolayer boron nitride and its thermal expansion. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav0129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Connell, J.W. Advances in 2D boron nitride nanostructures: Nanosheets, nanoribbons, nanomeshes, and hybrids with graphene. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 6908–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, S.; Fukushima, S.; Shimatani, M. Hexagonal Boron Nitride for Photonic Device Applications: A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokanathan, M.; Acharya, P.V.; Ouroua, A.; Strank, S.M.; Hebner, R.E.; Bahadur, V. Review of Nanocomposite Dielectric Materials with High Thermal Conductivity. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1364–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Feng, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J. Two dimensional hexagonal boron nitride (2D-hBN): Synthesis, properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 11992–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Xu, Z.-Q.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Aharonovich, I.; Zhang, Y. Two-Dimensional Hexagonal Boron Nitride for Building Next-Generation Energy-Efficient Devices. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Wu, J.; Cheng, H.-M.; Kang, F. Two-Dimensional Materials for Thermal Management Applications. Joule 2018, 2, 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Lei, W.; Wu, Z.-S. Two-dimensional Boron Nitride for Electronics and Energy Applications. Energy Environ. Mater. 2022, 5, 10–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Ismail, P.M.; Humayun, M.; Bououdina, M. Hexagonal boron nitride: From fundamentals to applications. Desalination 2025, 599, 118442. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Zhang, X.; Puthirath, A.B.; Meiyazhagan, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Babu, G.; Susarla, S.; Saju, S.K.; Tran, M.K.; et al. Structure, Properties and Applications of Two-Dimensional Hexagonal Boron Nitride. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2101589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassabois, G.; Valvin, P.; Gil, B. Hexagonal boron nitride is an indirect bandgap semiconductor. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramaratne, D.; Weston, L.; Van de Walle, C.G. Monolayer to Bulk Properties of Hexagonal Boron Nitride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 25524–25529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.-H.; Yu, Y.-J.; Lee, C.; Dean, C.; Shepard, K.L.; Kim, P.; Hone, J. Electron tunneling through atomically flat and ultrathin hexagonal boron nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 243114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichel, E.K.; Miller, R.E.; Abrahams, M.S.; Buiocchi, C.J. Heat capacity and thermal conductivity of hexagonal pyrolytic boron nitride. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 4607–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Li, J.; Lindsay, L.; Cherns, D.; Pomeroy, J.W.; Liu, S.; Edgar, J.H.; Kuball, M. Modulating the thermal conductivity in hexagonal boron nitride via controlled boron isotope concentration. Commun. Phys. 2019, 2, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Qian, X.; Yang, R.; Lindsay, L. Anisotropic thermal transport in bulk hexagonal boron nitride. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018, 2, 064005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Scullion, D.; Gan, W.; Falin, A.; Cizek, P.; Liu, S.; Edgar, J.H.; Liu, R.; Cowie, B.C.C.; Santos, E.J.G.; et al. Outstanding Thermal Conductivity of Single Atomic Layer Isotope-Modified Boron Nitride. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 085902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, J.; Dong, L.; Aiyiti, A.; Xu, X.; Li, B. Superior thermal conductivity in suspended bilayer hexagonal boron nitride. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falin, A.; Cai, Q.; Santos, E.J.G.; Scullion, D.; Qian, D.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Z.; Huang, S.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; et al. Mechanical properties of atomically thin boron nitride and the role of interlayer interactions. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Basu, N.; Shin, H.S. Large-area single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride: From growth mechanism to potential applications. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2023, 4, 041306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, Y.H. Synthesis of hexagonal boron nitride heterostructures for 2D van der Waals electronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 6342–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meziani, M.J.; Sheriff, K.; Parajuli, P.; Priego, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Rao, A.M.; Quimby, J.L.; Qiao, R.; Wang, P.; Hwu, S.-J.; et al. Advances in Studies of Boron Nitride Nanosheets and Nanocomposites for Thermal Transport and Related Applications. ChemPhysChem 2022, 23, e202100645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jiménez, C.; Chow, A.; Smith McWilliams, A.D.; Martí, A.A. Hexagonal boron nitride exfoliation and dispersion. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 16836–16873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darabdhara, G.; Borthakur, P.; Boruah, P.K.; Sen, S.; Pemmaraju, D.B.; Das, M.R. Advancements in two-dimensional boron nitride nanostructures: Properties, preparation methods, and their biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 11540–11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Park, C.-H.; Ihm, J. A Rigorous Method of Calculating Exfoliation Energies from First Principles. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 2759–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, E.; Dehghani Barenji, A.; Esmaeilzadeh Khabazi, M.; Najafi Chermahini, A. Boron nitride nanosheets: A comprehensive review of synthesis and multifunctional applications. Results Chem. 2025, 17, 102655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacilé, D.; Meyer, J.C.; Girit, Ç.Ö.; Zettl, A. The two-dimensional phase of boron nitride: Few-atomic-layer sheets and suspended membranes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 133107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Chen, Y.; Behan, G.; Zhang, H.; Petravic, M.; Glushenkov, A.M. Large-scale mechanical peeling of boron nitride nanosheets by low-energy ball milling. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 11862–11866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Mochalin, V.N.; Liu, D.; Qin, S.; Gogotsi, Y.; Chen, Y. Boron nitride colloidal solutions, ultralight aerogels and freestanding membranes through one-step exfoliation and functionalization. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, B.; Park, K.H.; Ryu, H.J.; Jeon, S.; Hong, S.H. Scalable Exfoliation Process for Highly Soluble Boron Nitride Nanoplatelets by Hydroxide-Assisted Ball Milling. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Yang, W.; Che, S.; Sun, L.; Li, H.; Ma, G.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Green preparation of high-yield and large-size hydrophilic boron nitride nanosheets by tannic acid-assisted aqueous ball milling for thermal management. Compos.-A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 164, 107266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, C.; Bando, Y.; Tang, C.; Kuwahara, H.; Golberg, D. Large-Scale Fabrication of Boron Nitride Nanosheets and Their Utilization in Polymeric Composites with Improved Thermal and Mechanical Properties. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2889–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.N.; Lotya, M.; O’Neill, A.; Bergin, S.D.; King, P.J.; Khan, U.; Young, K.; Gaucher, A.; De, S.; Smith, R.J.; et al. Two-Dimensional Nanosheets Produced by Liquid Exfoliation of Layered Materials. Science 2011, 331, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Williams, T.V.; Xu, T.-B.; Cao, W.; Elsayed-Ali, H.E.; Connell, J.W. Aqueous Dispersions of Few-Layered and Monolayered Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets from Sonication-Assisted Hydrolysis: Critical Role of Water. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 2679–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.-G.; Mao, N.-N.; Wang, H.-X.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.-L. A Mixed-Solvent Strategy for Efficient Exfoliation of Inorganic Graphene Analogues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10839–10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Kang, Q.; Jiang, P.; Huang, X. Rapid, high-efficient and scalable exfoliation of high-quality boron nitride nanosheets and their application in lithium-sulfur batteries. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 2424–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, Q.; Yu, H.; Bulin, C.; Sun, H.; Li, R.; Ge, X.; Xing, R. High-Efficient Liquid Exfoliation of Boron Nitride Nanosheets Using Aqueous Solution of Alkanolamine. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yang, G.; Wang, H.; Yan, C.; Sun, R.; Wong, C.-P. A universal method for large-yield and high-concentration exfoliation of two-dimensional hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets. Mater. Today 2019, 27, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, M.; Fu, L.; Duan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Guo, L.; Kang, R.; et al. Enhanced Thermal Conductivity of Polyimide Composites with Boron Nitride Nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Ortiz, D.; Pochat-Bohatier, C.; Cambedouzou, J.; Bechelany, M.; Miele, P. Exfoliation of Hexagonal Boron Nitride (h-BN) in Liquide Phase by Ion Intercalation. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kim, D.; Park, S.; Lee, S.-T.; Hong, J.; Lee, S.; Pak, S. Scalable High-Yield Exfoliation of Hydrophilic h-BN Nanosheets via Gallium Intercalation. Inorganics 2025, 13, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.; Fu, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, N.; Yu, J. Enhanced thermal conductivity of poly(vinylidene fluoride)/boron nitride nanosheet composites at low filler content. Compos.-A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 109, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Meng, Y.; Fu, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, G.; Gao, W.; Huang, X.; Lu, F. High-Yield Production of Boron Nitride Nanosheets and Its Uses as a Catalyst Support for Hydrogenation of Nitroaromatics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 9881–9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Bi, J. Scalable production of boron nitride nanosheets in ionic liquids by shear-assisted thermal treatment. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 7776–7782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, T.; Okamoto, H.; Katagiri, Y.; Matsushita, M.; Fukumori, K. A high-yield ionic liquid-promoted synthesis of boron nitride nanosheets by direct exfoliation. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12068–12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-R.; Ding, J.-H.; Shao, Z.-Z.; Xu, B.-Y.; Zhou, Q.-B.; Yu, H.-B. High-Quality Boron Nitride Nanosheets and Their Bioinspired Thermally Conductive Papers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 37247–37255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Jia, X.; Lan, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Shao, D.; Feng, L.; Song, H. Efficient exfoliation and functionalization of hexagonal boron nitride using recyclable ionic liquid crystal for thermal management applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osada, R.; Hoshino, T.; Okada, K.; Ohmasa, Y.; Yao, M. Surface tension of room temperature ionic liquids measured by dynamic light scattering. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 184705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, K.; Tan, Z.; Jia, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, S. Recent Advances in Chemical Vapor Deposition of Hexagonal Boron Nitride on Insulating Substrates. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.Y.; Kim, M.; Shin, H.S. Large-Area Hexagonal Boron Nitride Layers by Chemical Vapor Deposition: Growth and Applications for Substrates, Encapsulation, and Membranes. Acc. Mater. Res. 2022, 3, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukamachi, S.; Solís-Fernández, P.; Kawahara, K.; Tanaka, D.; Otake, T.; Lin, Y.-C.; Suenaga, K.; Ago, H. Large-area synthesis and transfer of multilayer hexagonal boron nitride for enhanced graphene device arrays. Nat. Electron. 2023, 6, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Hsu, A.; Jia, X.; Kim, S.M.; Shi, Y.; Hofmann, M.; Nezich, D.; Rodriguez-Nieva, J.F.; Dresselhaus, M.; Palacios, T.; et al. Synthesis of Monolayer Hexagonal Boron Nitride on Cu Foil Using Chemical Vapor Deposition. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Yi, G.-C. Synthesis of Atomically Thin h-BN Layers Using BCl3 and NH3 by Sequential-Pulsed Chemical Vapor Deposition on Cu Foil. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Ismach, A.; Chou, H.; Ferrer, D.A.; Wu, Y.; McDonnell, S.; Floresca, H.C.; Covacevich, A.; Pope, C.; Piner, R.; Kim, M.J.; et al. Toward the Controlled Synthesis of Hexagonal Boron Nitride Films. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 6378–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, C.; Toury, B.; Steyer, P.; Garnier, V.; Journet, C. Hexagonal boron nitride: A review on selfstanding crystals synthesis towards 2D nanosheets. J. Phys. Mater. 2021, 4, 044018. [Google Scholar]

- Kidambi, P.R.; Blume, R.; Kling, J.; Wagner, J.B.; Baehtz, C.; Weatherup, R.S.; Schloegl, R.; Bayer, B.C.; Hofmann, S. In Situ Observations during Chemical Vapor Deposition of Hexagonal Boron Nitride on Polycrystalline Copper. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 6380–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.M.; Hsu, A.; Park, M.H.; Chae, S.H.; Yun, S.J.; Lee, J.S.; Cho, D.-H.; Fang, W.; Lee, C.; Palacios, T.; et al. Synthesis of large-area multilayer hexagonal boron nitride for high material performance. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Wu, T.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Ding, F.; Xie, X.; Jiang, M. Synthesis of large single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride grains on Cu–Ni alloy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, Y.; Nakandakari, S.; Kawahara, K.; Yamasaki, S.; Mitsuhara, M.; Ago, H. Controlled Growth of Large-Area Uniform Multilayer Hexagonal Boron Nitride as an Effective 2D Substrate. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6236–6244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, L.; Qiao, R.; Wu, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Epitaxial growth of a 100-square-centimetre single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride monolayer on copper. Nature 2019, 570, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, D.; Mittendorfer, F.; Bertel, E. Quasiliquid Layer Promotes Hexagonal Boron Nitride (h-BN) Single-Domain Growth: H-BN on Pt(110). ACS Nano 2019, 13, 7083–7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Wu, Y.; Ren, C.; Gong, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, J.; Ma, L. A Descriptor-Driven Thermodynamic Framework for Achieving Unidirectional Nucleation in 2D Material Epitaxy. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 37972–37982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behura, S.; Nguyen, P.; Debbarma, R.; Che, S.; Seacrist, M.R.; Berry, V. Chemical Interaction-Guided, Metal-Free Growth of Large-Area Hexagonal Boron Nitride on Silicon-Based Substrates. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4985–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Hilse, M.; Huet, B.; Wang, K.; Kozhakhmetov, A.; Kim, J.H.; Bachu, S.; Alem, N.; Collazo, R.; Robinson, J.A.; et al. Substrate Modification during Chemical Vapor Deposition of hBN on Sapphire. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 54516–54526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Zhong, C.; Hao, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiao, J.; Yao, Y. Fabrication of BN thin films by chemical vapor deposition on 4H–SiC (0001) single-crystalline surfaces. Vacuum 2024, 222, 113009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Doh, K.-Y.; Moon, S.; Choi, C.-W.; Jeong, H.; Kim, J.; Yoo, W.; Park, K.; Chong, K.; Chung, C.; et al. Conformal Growth of Hexagonal Boron Nitride on High-Aspect-Ratio Silicon-Based Nanotrenches. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 2429–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K. Growth of Hexagonal Boron Nitride by MOCVD for Electronic and Photonic Applications. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2023, MA2023-02, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Im, S.; Kim, J.; Song, J.; Ji, C.; Pak, S.; Kim, J.K. Metal-organic chemical vapor deposition of hexagonal boron nitride: From high-quality growth to functional engineering. 2D Mater. 2025, 12, 042006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, G.; Gryzbowcki, G.; Hilton, A.; Muratore, C.; Snure, M. Growth of Multi-Layer hBN on Ni(111) Substrates via MOCVD. Crystals 2019, 9, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Cao, Y.; Yang, K.; Dong, H.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, Y. Review of boron nitride based polymer composites with ultrahigh thermal conductivity: Critical strategies and applications. Compos.-A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2026, 200, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Han, J.; Meziani, M.J.; Cao, L.; Yerra, S.; Collins, J.; Dumra, S.; Sun, Y.-P. Polymeric Nanocomposites of Boron Nitride Nanosheets for Enhanced Directional or Isotropic Thermal Transport Performance. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasul, M.G.; Kiziltas, A.; Arfaei, B.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R. 2D boron nitride nanosheets for polymer composite materials. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 2021, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Yu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Mateti, S.; Li, L.H.; Chen, Y.I. Hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets: Preparation, heat transport property and application as thermally conductive fillers. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 138, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yang, D.; Jiang, X.; Bando, Y.; Wang, X. Thermal Conductivity Enhancement of Polymeric Composites Using Hexagonal Boron Nitride: Design Strategies and Challenges. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Gao, J.; Dai, W.; Ma, H.; Nishimura, K.; Yu, J.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, N.; Lin, C.-T. A Mini Review of Flexible Heat Spreaders Based on Functionalized Boron Nitride Nanosheets. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2025, 147, 031401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-C.; Zhang, L.; Kretinin, A.V.; Morozov, S.V.; Wang, Y.B.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Ren, F.; Zhang, J.; Lu, C.-Y.; et al. High thermal conductivity of hexagonal boron nitride laminates. 2D Mater. 2016, 3, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Yang, Z.; Xie, H.; Jiang, P.; Dai, J.; Luo, W.; Yao, Y.; Hitz, E.; Yang, R.; et al. High temperature thermal management with boron nitride nanosheets. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, P. 3D Vertically Aligned BNNS Network with Long-Range Continuous Channels for Achieving a Highly Thermally Conductive Composite. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 28943–28952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liu, W.; Deng, L.; Shu, B. The Influence of Microsecond Pulsed Electric Field and Direct Current Electric Field on the Orientation Angle of Boron Nitride Nanosheets and the Thermal Conductivity of Epoxy Resin Composites. Micromachines 2025, 16, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Bai, X.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Oriented BN/Silicone rubber composite thermal interface materials with high out-of-plane thermal conductivity and flexibility. Compos.-A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 152, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Feng, Y.; Feng, W. Three-dimensional interconnected networks for thermally conductive polymer composites: Design, preparation, properties, and mechanisms. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2020, 142, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Qian, X.; Yang, R. Thermal conductivity of polymers and polymer nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2018, 132, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargar, F.; Barani, Z.; Salgado, R.; Debnath, B.; Lewis, J.S.; Aytan, E.; Lake, R.K.; Balandin, A.A. Thermal Percolation Threshold and Thermal Properties of Composites with High Loading of Graphene and Boron Nitride Fillers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 37555–37565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, X. Novel Functionalized BN Nanosheets/Epoxy Composites with Advanced Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 6503–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Calventus, Y.; Román, F.; Hutchinson, J.M. Achieving High Thermal Conductivity in Epoxy Composites: Effect of Boron Nitride Particle Size and Matrix-Filler Interface. Polymers 2019, 11, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, P. Cellulose Nanofiber Supported 3D Interconnected BN Nanosheets for Epoxy Nanocomposites with Ultrahigh Thermal Management Capability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1604754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Du, G.; Gao, W.; Bai, H. An Anisotropically High Thermal Conductive Boron Nitride/Epoxy Composite Based on Nacre-Mimetic 3D Network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1900412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, S.; Huang, K.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, L.; Lu, Z.; Wang, L. Salting-Out Effect Protected Ball-Milling Exfoliation of Hexagonal Boron Nitride and the Scale Laws on the Thermal Conductivities of the Exfoliated Nanosheet Assembled Composite Films. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 7909–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, W.; Bai, H. Isotropically Ultrahigh Thermal Conductive Polymer Composites by Assembling Anisotropic Boron Nitride Nanosheets into a Biaxially Oriented Network. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 18959–18967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Tian, W.; Wang, L.; Luo, J.; Li, Q.; Fan, X.; Yao, Y. Enhanced through-plane thermal conductivity of boron nitride/epoxy composites. Compos.-A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 98, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, B.; Jiang, P. Highly Thermally Conductive Yet Electrically Insulating Polymer/Boron Nitride Nanosheets Nanocomposite Films for Improved Thermal Management Capability. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, K.; Shi, X.; Guo, Y.; Gu, J. Interfacial thermal resistance in thermally conductive polymer composites: A review. Compos. Commun. 2020, 22, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.-W.; Wang, F.; Wan, B. Polymer composites with high thermal conductivity: Theory, simulation, structure and interfacial regulation. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 148, 101362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Che, S.; Gao, C.; Jiang, B.; Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Amino acid functionalized boron nitride nanosheets towards enhanced thermal and mechanical performance of epoxy composite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 619, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Wang, Y. Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets: Properties, Preparation and Applications in Thermal Management. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020101

Liu M, Wang Y. Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets: Properties, Preparation and Applications in Thermal Management. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020101

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Min, and Yilin Wang. 2026. "Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets: Properties, Preparation and Applications in Thermal Management" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020101

APA StyleLiu, M., & Wang, Y. (2026). Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets: Properties, Preparation and Applications in Thermal Management. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020101