Laser-Controlled Propulsion of a Microbubble Rolling on a Carbon Nanocoil Rail

Abstract

1. Introduction

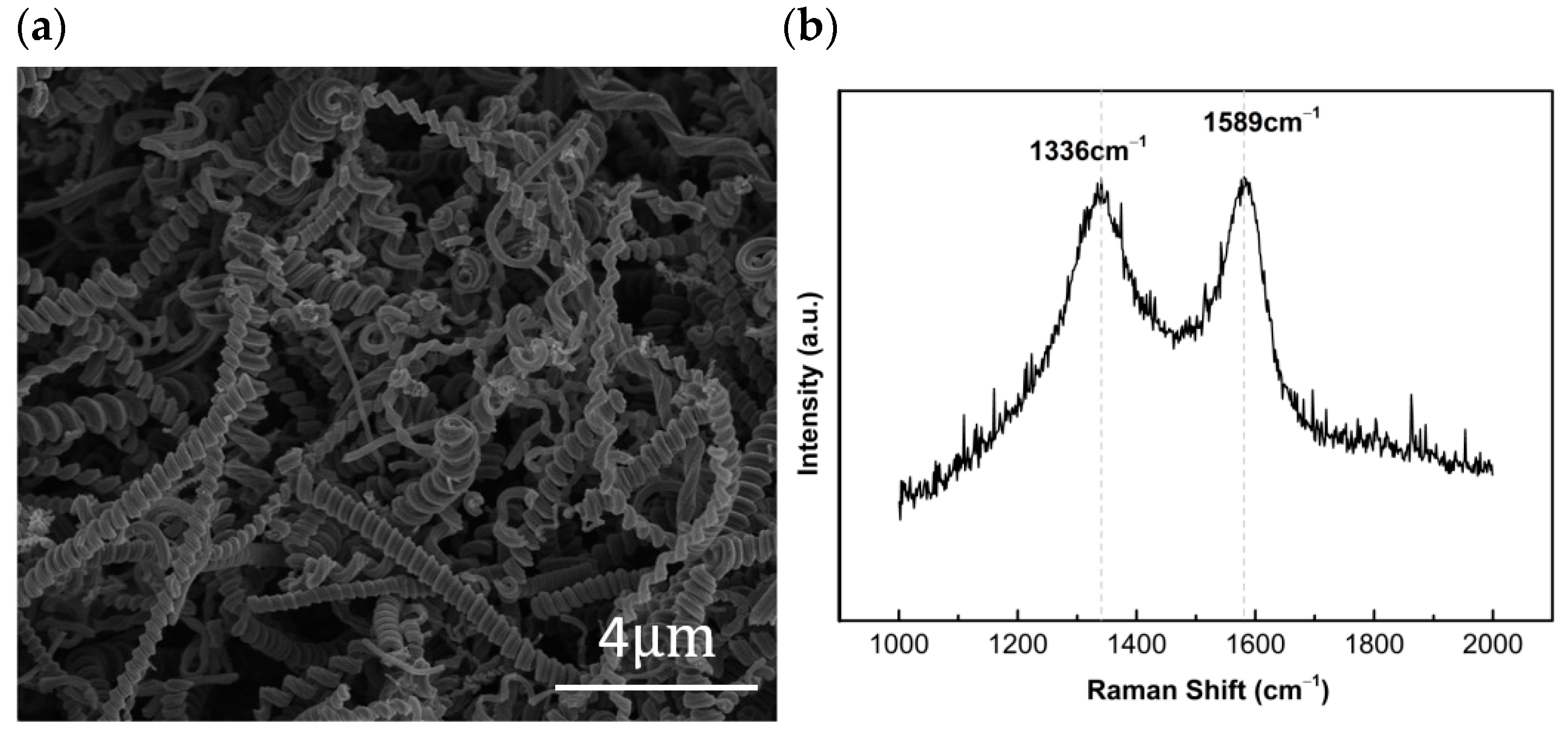

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of a Paraffin/Carbon Nanocoil Mixed Sample

2.2. The Design of Microfluidic Chip

3. Results

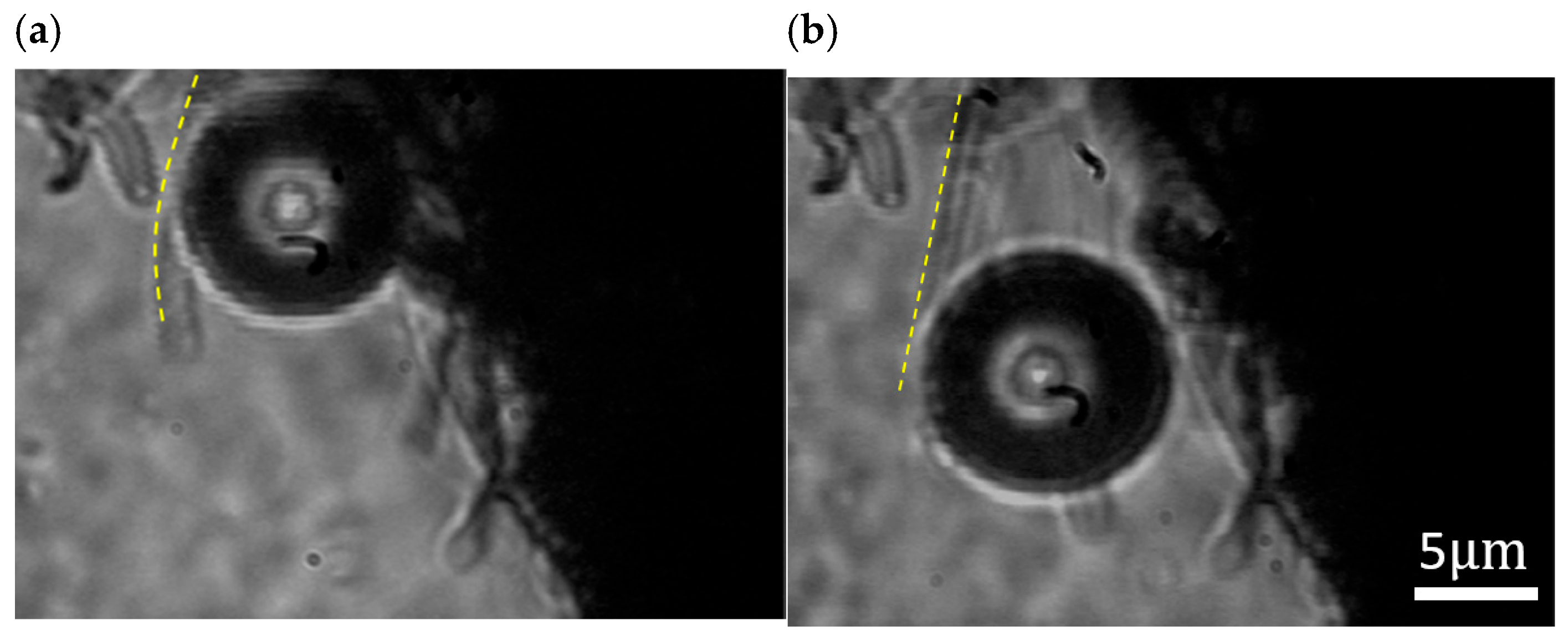

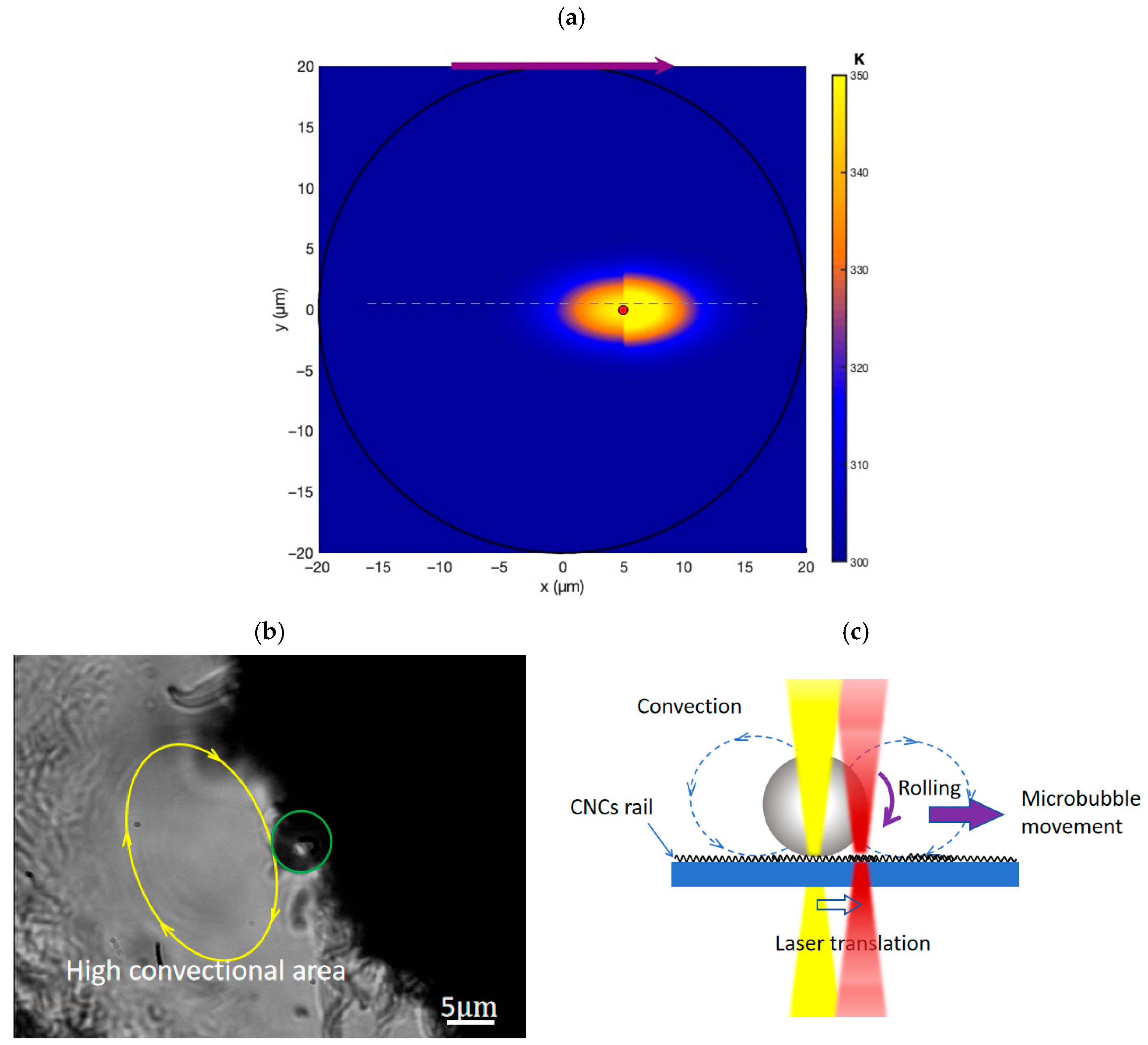

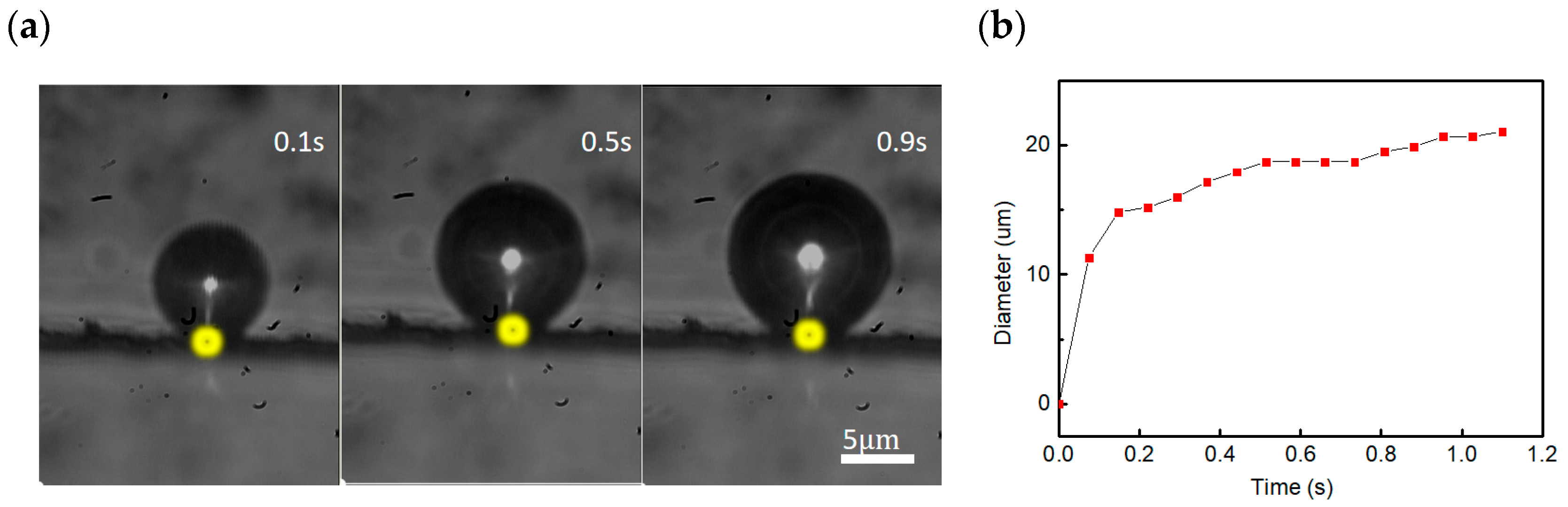

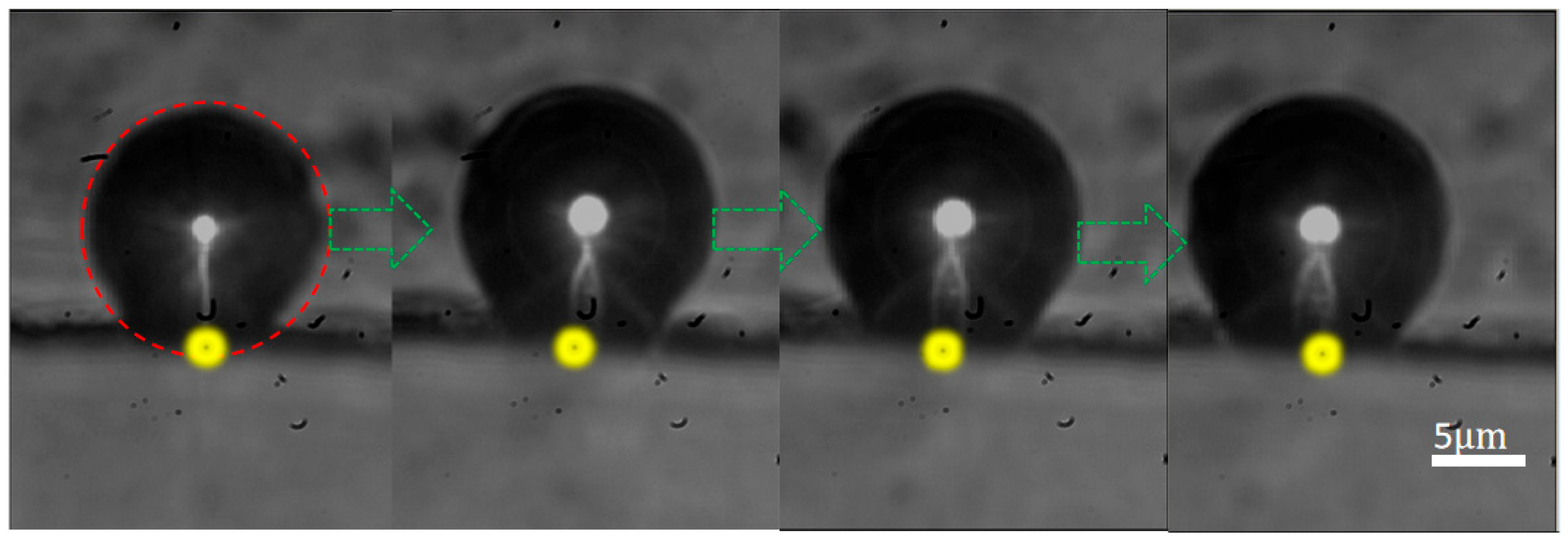

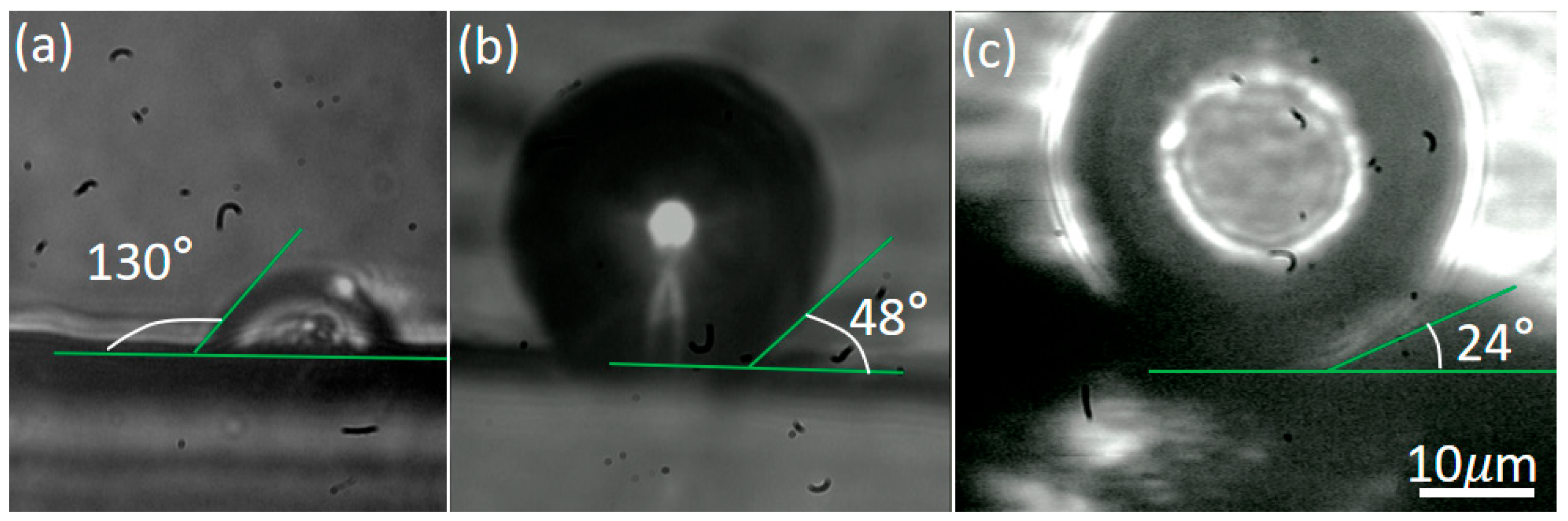

3.1. Laser-Controlled Microbubble Roiling Motion on CNC Rails

3.2. Laser-Controlled Microbubble Roiling Motion Within a Microchannel Chip

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prudhomme, M.; Lakhdar, C.; Fattaccioli, J.; Addouche, M. Functionalization of microbubbles in a microfluidic chip for biosensing application. Biomed. Microdevices 2024, 26, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Ge, L. An easily assembled double T-shape microfluidic devices for the preparation of submillimeter-sized polyacronitrile (PAN) microbubbles and polystyrene (PS) double emulsions. Colloids Surf. A Phys. Eng. Asp. 2015, 468, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.-R.; Tan, Y.-D.; Shen, X.-J.; Zhu, K.-Y.; Bao, L.-P. Mechanism of contrast-enhancement in ultrasound-modulated laser feedback imaging with ultrasonicmicrobubble contrast agent. Acta Phys. Sin. 2019, 68, 214304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yin, K.; Dong, X.R.; He, J.; Duan, J.-A. Laser structuring of underwater bubble-repellent surface. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 8381–8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Xing, X.; Yu, A.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, X.; Jurcik, B. Enhanced ozonation of simulated dyestuff wastewater bymicrobubbles. Chemosphere 2007, 68, 1854–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edzwald, J.K. Principles and applications of dissolved air flotation. Water Sci. Technol. 1995, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Jan Cornel, E.; Du, J. Ultrasound-Responsive Polymer-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Guo, Y.; Foiret, J.; Tumbale, S.K.; Paulmurugan, R.; Ferrara, K.W. Protocol for In Vitro Sonoporation Validation Using Non-Targeted Microbubbles for Human Studies of Ultrasound-Mediated Gene Delivery. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jin, H.; Tao, X.; Xu, B.; Lin, S. Photo-switchable smart superhydrophobic surface with controllable superwettability. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 5303–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Yu, H.-C.; Park, K.-M.; Lee, H.-D. Development of an Air Bubble-Based Cleaning Device for Enoki Mushroom Plastic Sleeve. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2025, 26, 516–524. [Google Scholar]

- AziziHariri, P.; Ebrahimi, A.H.; Zamyad, H.; Sahebian, S. Development of a phase-change material-based soft actuator for soft robotic gripper functionality: In-depth analysis of material composition, ethanol microbubble distribution and lifting capabilities. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 311, 128435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobo, D.; Pinchasik, B.-E. Backswimmer-Inspired Miniature 3D-Printed Robot with Buoyancy Autoregulation through Controlled Nucleation and Release of Microbubbles. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2200010. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.; Vega-Sánchez, C.; Mehta, P.; Zhang, X.; Neto, C. Experimental Study of Gas Microbubbles on Oil-Infused Wrinkled Surfaces. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, 2500160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Brookes, A.; Carra, I.; Jefferson, B.; Jarvis, P. Understanding the difference between the nano and micro bubble size distributions generated by a regenerative turbine microbubble generator using ozone. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmin, R.A.; Rudakovskaya, P.G.; Gusliakova, O.I.; Sindeeva, O.A.; Prikhozhdenko, E.S.; Maksimova, E.A.; Obukhova, E.N.; Chernyshev, V.S.; Khlebtsov, B.N.; Solovev, A.A.; et al. Air-Filled Bubbles Stabilized by Gold Nanoparticle/Photodynamic Dye Hybrid Structures for Theranostics. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 415. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ye, X.; Huang, T.; Tu, X.; Shum, P.P. Coherent Manipulation of Optomechanical Modes in Mechanically Coupled Microbubble Resonators. ACS Photonics 2025, 12, 4678–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Tang, G.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Q. Manipulation of submicron particles in fluid using microbubbles in microporous arrays as seeds. Appl. Acoust. 2025, 231, 110426. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, M.A.; Wu, M.; Ren, W.; Jensen, M.A.; Davis, R.W.; Hesselink, L. Spectral Tweezers: Single Sample Spectroscopy Using Optoelectronic Tweezers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 124, 071104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, A.; Neupane, K.; Jung, H.; Neuman, K.C.; Woodside, M.T. Nonlinear Effects in Optical Trapping of Titanium Dioxide and Diamond Nanoparticles. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 3439–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, K.C.; Abbondanzieri, E.A.; Block, S.M. Measurement of the Effective Focal Shift in an Optical Trap. Opt. Lett. 2005, 30, 1318–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pethig, R. Dielectrophoresis Tutorial: Inspired by Hatfield’s 1924 Patent and Boltzmann’s Theory and Experiments of 1874. Electrophoresis 2005, 46, 1195–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaee, A.; Mirhoseini, M.; Jannati, K. A novel micromixer utilizing thermocapillary-driven bubbles: An investigation using the lattice Boltzmann method. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 072110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Rafiei, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Pourjafar-Chelikdani, M.; Sadeghy, K. Dynamics of Microbubbles Oscillating in Rheopectic Fluids Subject to Acoustic Pressure Field. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2023, 16, 1916–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAli, O.; Saha, A.; Coimbra, C.F.M. Thermocapillary instabilities in bubbles undergoing heat and mass transfer. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 083322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kollipara, P.S.; Liu, Y.; Yao, K.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y. Opto-Thermocapillary Nanomotors on Solid Substrates. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 8820–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Kirkinis, E.; Olvera de la Cruz, M. Thermocapillary Migrating Odd Viscous Droplets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 198201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, T.K.; Kim, C.-J. Valveless Pumping Using Traversing Vapor Bubbles in Microchannels. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 83, 5658–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, T.; Togo, H.; Makihara, M.; Shimokawa, F.; Kaneko, K. Improvement of Switching Time in a Thermocapillarity Optical Switch. J. Light. Technol. 2001, 19, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Darhuber, A.A.; Valentino, J.P.; Davis, J.M.; Troian, S.M.; Wagner, S. Microfluidic actuation by modulation of surface stresses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.I.; Aaron, T.O.; Wenqi, H. Micro-assembly using optically controlled bubble microrobots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 094103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, A.; Zhao, M.; Jin, S.; Ye, G.; Wang, C. Three-Dimensional Manipulation of Micromodules Using Twin Optothermally Actuated Bubble Robots. Micromachines 2024, 15, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.-Y.; Tu, C.-H.; Liaw, J.-W.; Kuo, M.-K. Laser-Induced Plasmonic Nanobubbles and Microbubbles in Gold Nanorod Colloidal Solution. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, H. Light-induced enhanced phase change process of plasmonic nanofluids: The reduction of the latent heat of vaporization. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 240, 122140. [Google Scholar]

- Candreva, A.; De Rose, R.; Perrotta, I.D.; Guglielmelli, A.; La Deda, M. Light-Induced Clusterization of Gold Nanoparticles: A New Photo-Triggered Antibacterial against E. coli Proliferation. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urabe, Y.; Monjushiro, H.; Watarai, H. Laser-Thermophoresis and Magnetophoresis of a Micro-Bubble in Organic Liquids. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 125126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N.A.; Bezuglyĭ, B.A. Optical Thermocapillary Bubble Trap. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2006, 32, 854–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, A.T.; Jamshidi, A.; Valley, J.K.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Wu, M.C. Optically actuated thermocapillary movement of gas bubbles on an absorbing Substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 074103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, N.; Song, H.; Liu, Y.; Hai, L.; Cao, J.; Wang, G. Visible light-driven multi-motion modes CNC/TiO2 nanomotors for highly efficient degradation of emerging contaminants. Carbon 2019, 155, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Jiang, J.-W.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Rabczuk, T. Thermal conductivity of carbon nanocoils. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 233511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Pan, L.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Qiu, J. Thermal conductivity of a single carbon nanocoil measured by field-emission induced thermal radiation. Carbon 2012, 50, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, J.; Lu, X.; He, X. Nanoparticle systems reduce systemic toxicity in cancer treatment. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Pan, L.J.; Ma, H.; Cui, R. Electromechanical vibrationof carbon nanocoils. Carbon 2015, 81, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Li, C.W.; Zhao, M.; Shen, J.; Pan, L.J. A microfluidics vapor-membrane-valve generated by laser irradiation on carbon nanocoils. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 20248–20254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Sun, R.; Li, L.X.; Shen, J.; Pan, L.J. Carbon Nanocoil-Based Photothermal Conversion Carrier for Microbubble Transport. Coatings 2023, 13, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.K.; Jung, Y.; Choi, C.J.; Ko, J.S. Highly reliable superhydrophobic surface with carbon nanotubes immobilized on aPDMS/adhesive multilayer. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 12956–12966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, R.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Wu, X.; Xi, X.; Pan, L. A Light-Driven Carbon Nanocoil Microrobot. Coatings 2024, 14, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pan, L.; Li, C.; Zheng, J. Highly Efficient Near-Infrared Photothermal Conversion of a Single Carbon Nanocoil Indicated by Cell Ejection. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 27696–27701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, P.; Murali, K.; Idichandy, V.G. Experimental investigation of hydrodynamic force coefficients over AUV hull form. Ocean. Eng. 2009, 36, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pan, L.; Deng, C.; Li, C. Tearing-off method based on single carbon nanocoil for liquid surface tension measurement. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 55, 118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lu, X.; Song, H.; Wang, G. Preparation and Application of Hydrophobic and Breathable Carbon Nanocoils/Thermoplastic Polyurethane Flexible Strain Sensors. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.M.; Wang, C.; Pan, L.J.; Fu, X.; Yin, P.; Zou, H. Electrical Conductivity of Single Polycrystalline-Amorphous Carbon Nanocoils. Carbon 2016, 98, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Cong, T.; Yang, S.; Chen, H.; Qin, J.; Usman, M.; Fan, Z.; Pan, L.J. Growth of Carbon Nanocoils byPorous α-Fe2O3/SnO2 Catalyst and Its Buckypaper for High Efficient Adsorption. Nanomicro Lett. 2020, 12, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Pan, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, T. Micro-bubble generated by laser irradiation on an individual carbon nanocoil. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 345, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.B.; Guénonet, S.; Gross, B.; Yuan, J.; Jiang, Z.G.; Zhong, Y.Y.; Grünzweig, M.; Iishi, A.; Wu, P.H.; Hatano, T.; et al. Coherent Terahertz Emission of Intrinsic Josephson Junction Stacks in the Hot Spot Regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 057002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Peng, X.; Wang, M.; Scarabelli, L.; Mao, Z.; Liz-Marzán, L.M.; Becker, M.F.; Zheng, Y. Light-Directed Reversible Assembly of Plasmonic Nanoparticles Using Plasmon-Enhanced Thermophoresis. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 9659–9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Li, W.; Yang, F.; Chang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Khan, J.; Li, C. Force analysis and bubble dynamics during flow boiling in silicon nanowire microchannels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 101, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.E.; Chidangil, S.; George, S.D. Recent Progress in Fabricating Superaerophobic and Superaerophilic Surfaces. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1601088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.D.; Chidangil, S.; Mathur, D. Minireview: Laser-Induced Formation of Microbubbles—Biomedical Implications. Langmuir 2019, 35, 10139–10150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, R.; Banerjee, P.; Sudesh, K.S. Molecular dynamics studies on interfacial interactions between imidazolium-based ionic liquids and carbon nanotubes. Struct. Chem. 2024, 35, 1743–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, M.; Shen, J.; Pan, L. Laser-Controlled Propulsion of a Microbubble Rolling on a Carbon Nanocoil Rail. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010005

Liu Y, Li S, Sun Y, Li J, Dai Y, Zhang M, Shen J, Pan L. Laser-Controlled Propulsion of a Microbubble Rolling on a Carbon Nanocoil Rail. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yuli, Si Li, Yanming Sun, Jinlu Li, Yuanyong Dai, Mengmeng Zhang, Jian Shen, and Lujun Pan. 2026. "Laser-Controlled Propulsion of a Microbubble Rolling on a Carbon Nanocoil Rail" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010005

APA StyleLiu, Y., Li, S., Sun, Y., Li, J., Dai, Y., Zhang, M., Shen, J., & Pan, L. (2026). Laser-Controlled Propulsion of a Microbubble Rolling on a Carbon Nanocoil Rail. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010005