Facile Galvanic Replacement Toward One-Dimensional Cu-Based Bimetallic Nanobelts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

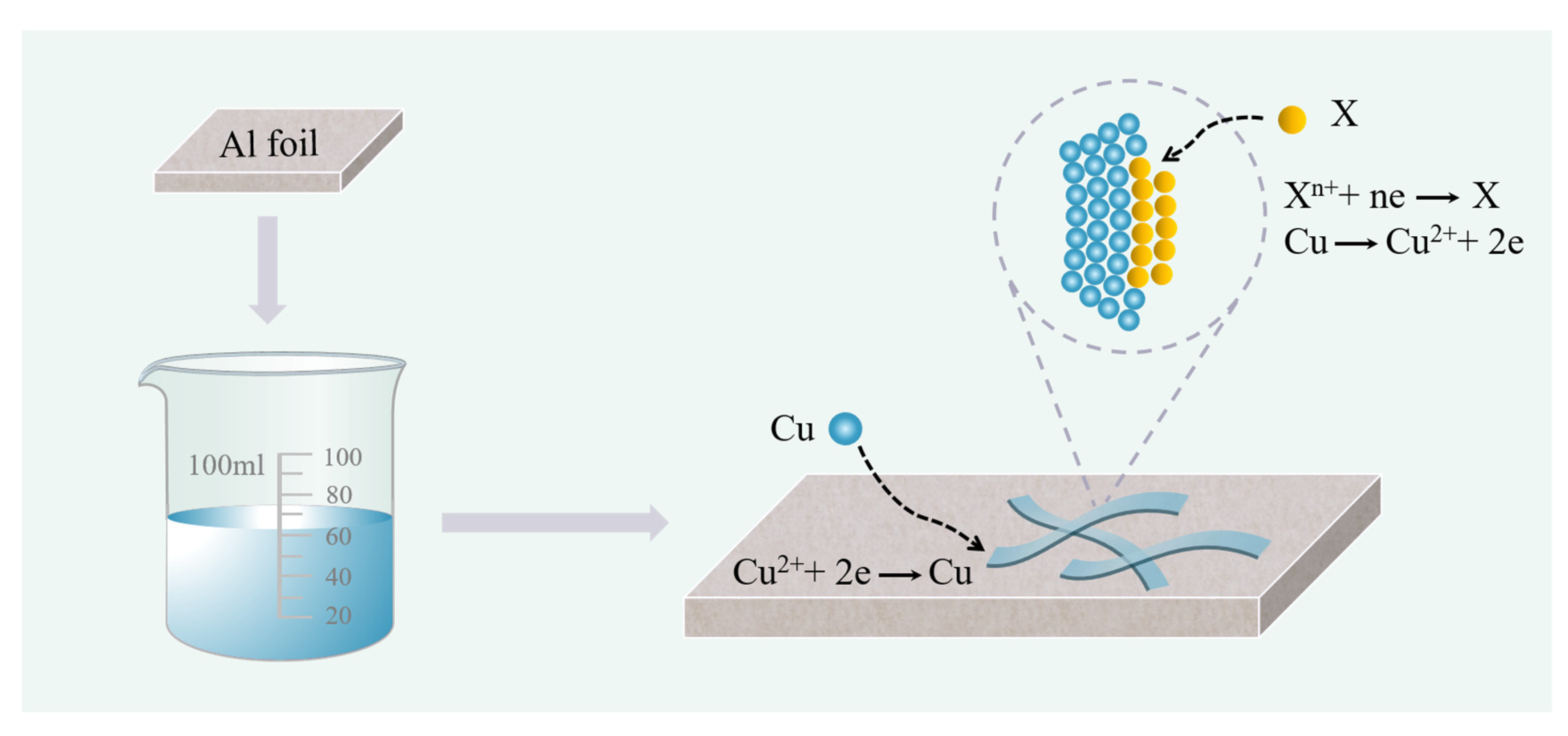

2.2. Preparation of Cu@CuO-X (Ag, Bi) Nanobelts

2.3. Sample Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, G.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, X.; Li, Q.; Kang, L. One-Dimensional High-Entropy Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 8464–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Walther, A. 1D Colloidal Chains: Recent Progress from Formation to Emergent Properties and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 4023–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, D.; Kim, M.J.; Lyu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Wiley, B.J.; Xia, Y. One-Dimensional Metal Nanostructures: From Colloidal Syntheses to Applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8972–9073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Nara, H.; Asakura, Y.; Hamada, T.; Yan, P.; Earnshaw, J.; An, M.; Eguchi, M.; Yamauchi, Y. End-to-End Pierced Carbon Nanosheets with Meso-Holes. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2409546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Leong, K.K.; Amiralian, N.; Bando, Y.; Ahamad, T.; Alshehri, S.M.; Yamauchi, Y. Nanoarchitectured MOF-Derived Porous Carbons: Road to Future Carbon Materials. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2024, 11, 041302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Kwon, S.; Kim, H.; Park, S. Colloidal Synthesis of Plasmonic Complex Metal Nanoparticles: Sequential Execution of Multiple Chemical Toolkits Increases Morphological Complexity. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 7321–7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Nabi, A.G.; Palma, M.; Di Tommaso, D. Copper Nanowires for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Reaction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 27883–27898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Y.; Mao, X.; Gao, X.; Xu, D. Surface Plasmon Enhancement of 1D Ag Nanowires Modified Electro-Treated BiVO4 Photoanode with Abundant Oxygen Vacancies for Solar Water Oxidation. Fuel 2024, 370, 131847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, I.; Wang, S.; Santos, H.L.; Kitching, E.; Pakala, P.; Chundak, M.; Ritala, M.; Haigh, S.J.; Slater, T.J.A.; Camargo, P.H.C. Plasmonically Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution on Anisotropic AuPt Nanowires with Submonolayer Pt Surface Coverage. Small 2025, 21, e10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Jin, H.; Wang, Y. Recent Progress on the Synthesis of Metal Alloy Nanowires as Electrocatalysts. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 2488–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Xu, L.; Ma, C.; Cao, W.; Lu, Q. Ultrathin High-Entropy Alloy Nanowires as a Bi-Functional Catalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction and Methanol Oxidation Reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 28019–28025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattarozzi, F.; van der Willige, N.; Gulino, V.; Keijzer, C.; van de Poll, R.C.J.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Ngene, P.; de Jongh, P.E. Oxide-Derived Silver Nanowires for CO2 Electrocatalytic Reduction to CO. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Tano, T.; Tryk, D.A.; Iiyama, A.; Uchida, M.; Kuwauchi, Y.; Masuda, A.; Kakinuma, K. Pt Nanorods Oriented on Gd-Doped Ceria Polyhedra Enable Superior Oxygen Reduction Catalysis for Fuel Cells. J. Catal. 2022, 407, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Lim, J.W.; Maji, R.C.; Maji, S.K. Graphene Oxide-Wrapped Gold Nanorods for Direct Plasmon-Enhanced Electrocatalysis to Detect Hydrogen Peroxide and in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 2729–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Zhang, T.; Dong, K.; Pu, H.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Y. Electrochemical Synthesis of Rh Nanorods with High-Index Facets for the Oxidation of Formic Acid. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 7353–7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Meng, Q.; Xiao, M.; Liu, C.; Xing, W.; Zhu, J. Insights into the Dynamic Surface Reconstruction of Electrocatalysts in Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Renewables 2024, 2, 272–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; Ma, Y.; An, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Fundamental Understanding of Structural Reconstruction Behaviors in Oxygen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhong, W.; Li, G.; Deng, D.; Fan, X.; Wu, Q. Surface Reconstruction Regulation of Catalysts for Cathodic Catalytic Electrosynthesis. Appl. Catal. O Open 2025, 202, 207036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Farzinpour, F.; Kornienko, N. Dynamic Active Sites behind Cu-Based Electrocatalysts: Original or Restructuring-Induced Catalytic Activity. Chem 2025, 11, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Yin, J.; Jin, J.; Hu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, Y.-Q.; Xi, P. Progress in In Situ Research on Dynamic Surface Reconstruction of Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2022, 3, 2200036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, G.H.; Kley, C.S.; Roldan Cuenya, B. Potential-Dependent Morphology of Copper Catalysts during CO2 Electroreduction Revealed by In Situ Atomic Force Microscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2561–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, P.; Yoon, A.; Rettenmaier, C.; Herzog, A.; Chee, S.W.; Roldan Cuenya, B. Dynamic Transformation of Cubic Copper Catalysts during CO2 Electroreduction and Its Impact on Catalytic Selectivity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirbeigiarab, R.; Tian, J.; Herzog, A.; Qiu, C.; Bergmann, A.; Roldan Cuenya, B.; Magnussen, O.M. Atomic-Scale Surface Restructuring of Copper Electrodes under CO2 Electroreduction Conditions. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Jin, W.; Tuo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, S.; Gong, T.; Li, J.; Ni, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. In Situ Construction of Highly Durable Cuδ+ Species Boosting Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to C2+ Products. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2025, 375, 125434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, X.; Fruehwald, H.; Akhmetzyanov, D.; Hanson, M.; Chen, Z.; Chen, N.; et al. Stabilized Cuδ+-OH Species on In Situ Reconstructed Cu Nanoparticles for CO2-to-C2H4 Conversion in Neutral Media. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yu, H.; Chow, Y.L.; Webley, P.A.; Zhang, J. Toward Durable CO2 Electroreduction with Cu-Based Catalysts via Understanding Their Deactivation Modes. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2403217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhimi, B.; Zhou, M.; Yan, Z.; Cai, X.; Jiang, Z. Cu-Based Materials for Enhanced C2+ Product Selectivity in Photo-/Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction: Challenges and Prospects. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Loiudice, A.; Kumar, K.; Zaza, L.; Buonsanti, R. Well-Defined Cu Precatalysts Indicate Design Rules for Reactivity in Nitrate Electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 35438–35445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, G. Designing Copper-Based Catalysts for Efficient Carbon Dioxide Electroreduction. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ruan, X.; Ganesan, M.; Wu, J.; Ravi, S.K.; Cui, X. Transition Metal-Based Catalysts for Urea Oxidation Reaction (UOR): Catalyst Design Strategies, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2313309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, A.S.; Pervaiz, E.; Khosa, R.; Sohail, U. An Inclusive Review and Perspective on Cu-Based Materials for Electrochemical Water Splitting. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 4963–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Xie, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, R.; Tian, M.; Chi, M.; Shao, M.; Xia, Y. Controlling the Surface Oxidation of Cu Nanowires Improves Their Catalytic Selectivity and Stability toward C2+ Products in CO2 Reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Fei, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Tan, X.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; et al. MOF-Derived Bimetallic CuBi Catalysts with Ultra-Wide Potential Window for High-Efficient Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 to Formate. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 298, 120571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yan, Q.; Yu, L.; Yan, T.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, L.; Xi, J. A Bi-Co Corridor Construction Effectively Improving the Selectivity of Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction toward Ammonia by Nearly 100%. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2306633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Ma, X.; Chen, T.; Xu, L.; Feng, J.; Wu, L.; Jia, S.; Zhang, L.; Tan, X.; Wang, R.; et al. Urea Synthesis via Coelectrolysis of CO2 and Nitrate over Heterostructured Cu-Bi Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 25813–25823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ji, Y.; Shao, Q.; Yin, R.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, X. Phase and Structure Modulating of Bimetallic CuSn Nanowires Boosts Electrocatalytic Conversion of CO2. Nano Energy 2019, 59, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; He, Y.; Yan, P.; Wang, S.; Dong, F. Boosted C-C Coupling with Cu-Ag Alloy Sub-Nanoclusters for CO2-to-C2H4 Photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2307320120. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Chen, B.; Mo, G.; Chen, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wu, Z. Recent Advances in Regulation Strategy and Catalytic Mechanism of Bi-Based Catalysts for CO2 Reduction Reaction. Nano-Micro Lett. 2026, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudian, M.R. L-cysteine-assisted synthesis of polypyrrole-coated copper nanobelts and their application in the detection of hydrazine. Microchem. J. 2022, 183, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Yuan, D.; Liu, S.; Bao, J.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, J. Facile synthesis of porous copper nanobelts and their catalytic performance. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012, 47, 4438–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, F. Ionic liquids as two-dimensional templates for the spontaneous assembly of copper nanoparticles into nanobelts and observation of an intermediate state. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Wang, C.; Qin, D.; Xia, Y. Galvanic Replacement Synthesis of Metal Nanostructures: Bridging the Gap between Chemical and Electrochemical Approaches. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutés, A.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R. Silver dendrites from galvanic displacement on commercial aluminum foil as an effective SERS substrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1476–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Hou, Z.; Wei, L.; Guan, S. Facile Galvanic Replacement Toward One-Dimensional Cu-Based Bimetallic Nanobelts. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010038

Xie Y, Sun Q, Li Y, Li W, Hou Z, Wei L, Guan S. Facile Galvanic Replacement Toward One-Dimensional Cu-Based Bimetallic Nanobelts. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Ying, Qitong Sun, Yuanyuan Li, Wanwan Li, Zhiwei Hou, Lihui Wei, and Sujun Guan. 2026. "Facile Galvanic Replacement Toward One-Dimensional Cu-Based Bimetallic Nanobelts" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010038

APA StyleXie, Y., Sun, Q., Li, Y., Li, W., Hou, Z., Wei, L., & Guan, S. (2026). Facile Galvanic Replacement Toward One-Dimensional Cu-Based Bimetallic Nanobelts. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010038