Promoting Drp1-Mediated Mitochondrial Division in Nickel Nanoparticles-Induced Reproductive Toxicity in GC-2 Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Line

2.2. Ni NPs

2.3. Characterization and Preparation of Ni NPs Suspension

2.4. In Vitro Cytotoxic Assay

2.5. Observation of Cell Morphology

2.6. Observation Cell Ultrastructure

2.7. Analysis of Cell Apoptosis

2.8. Analysis of Mitochondrial Morphology

2.9. Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

2.10. Determination of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (MtROS)

2.11. Measurement of Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP)

2.12. Measurement of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP)

2.13. Analysis of Western Blots

2.14. Optimal Conditions for Mdivi-1 and Dnm1l and Their Reverse Effects on the Ni NPs-Induced Toxicity

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Toxicity of Ni NPs on Reproductive Cells

3.1.1. Characterization of Ni NPs

3.1.2. Effect of Ni NPs on Cytotoxicity, Morphology, and Apoptosis

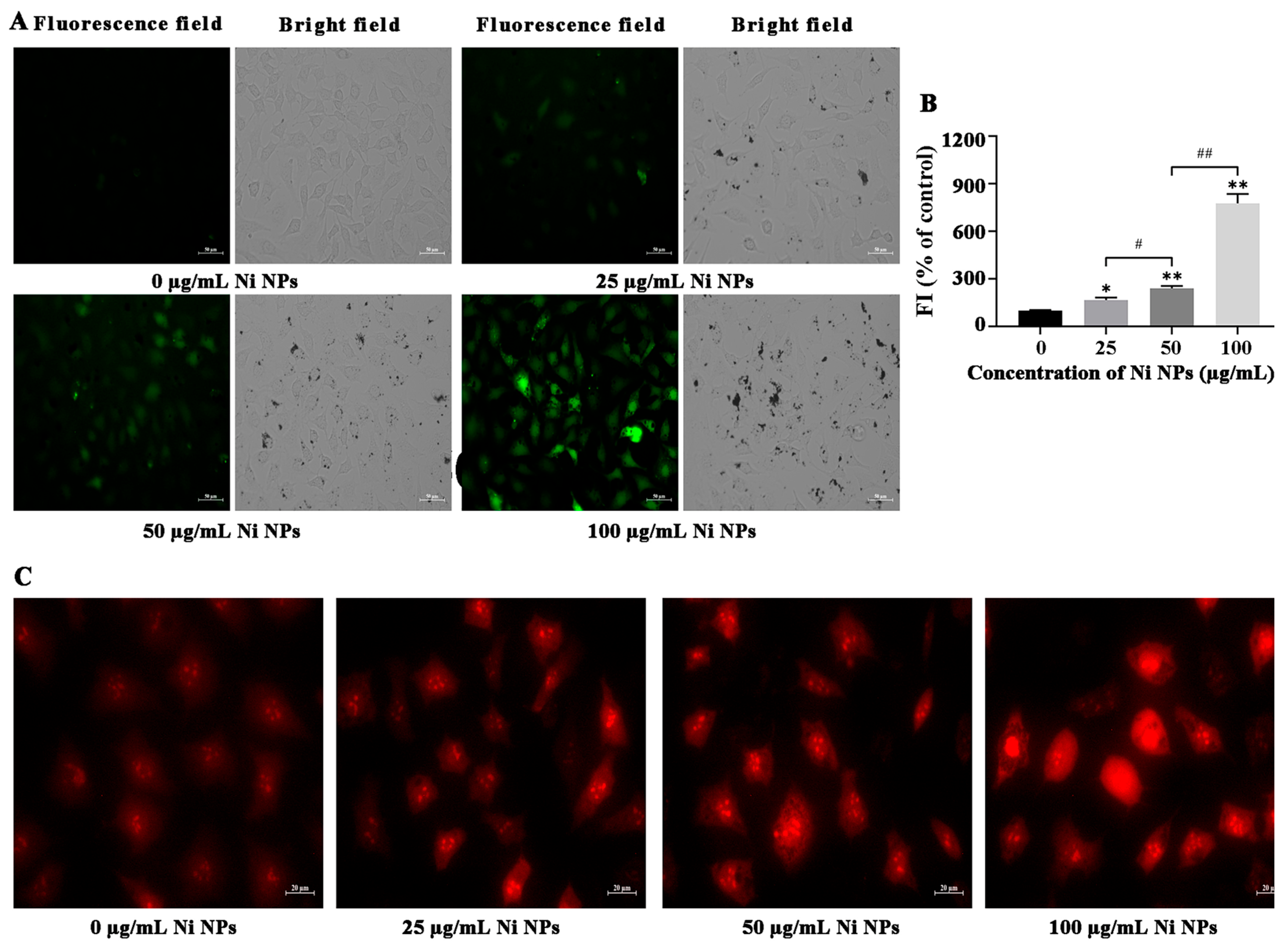

3.1.3. Effects of Ni NPs on Oxidative Stress

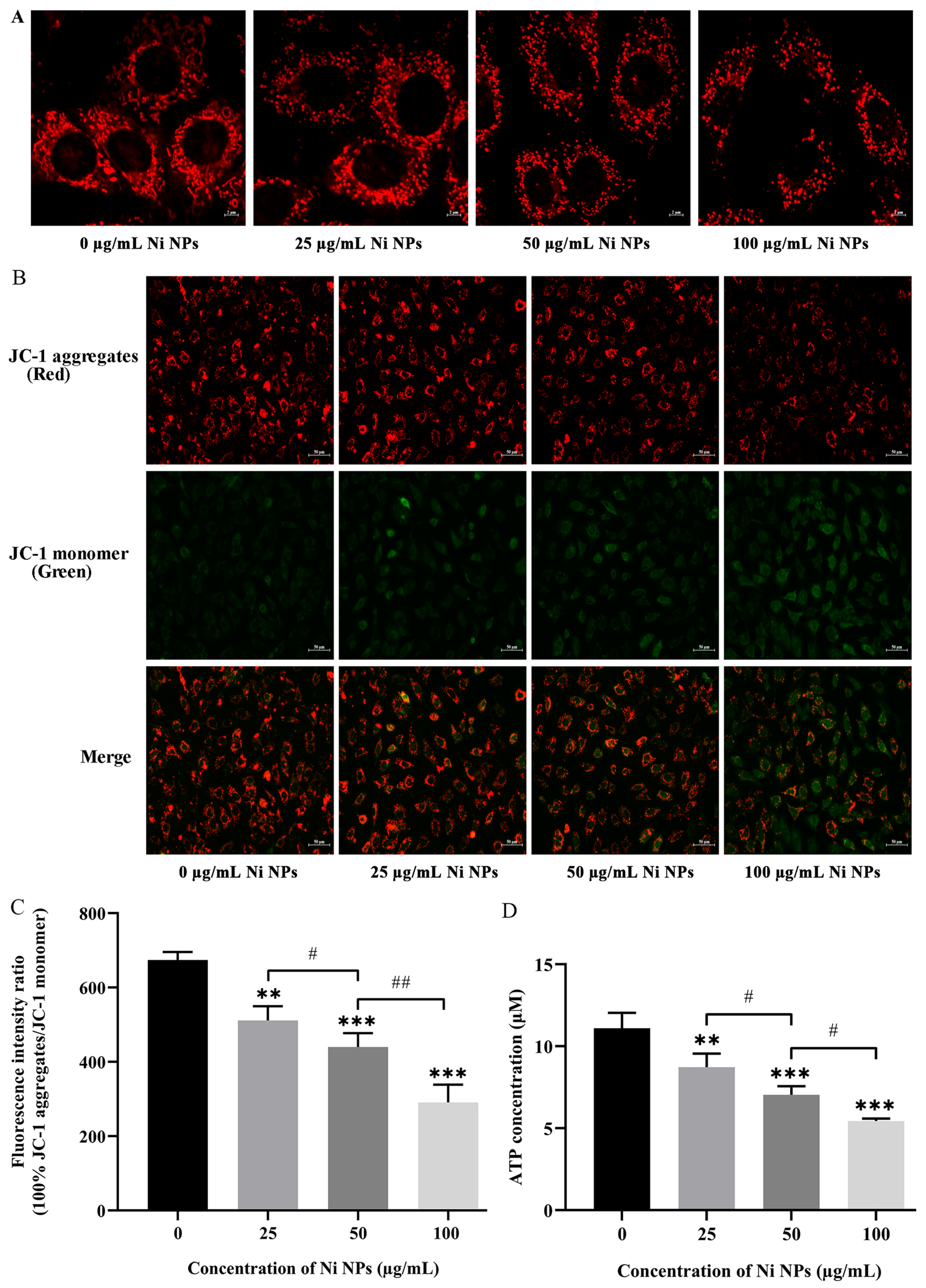

3.1.4. Effects of Ni NPs on Mitochondrial Structure and Function

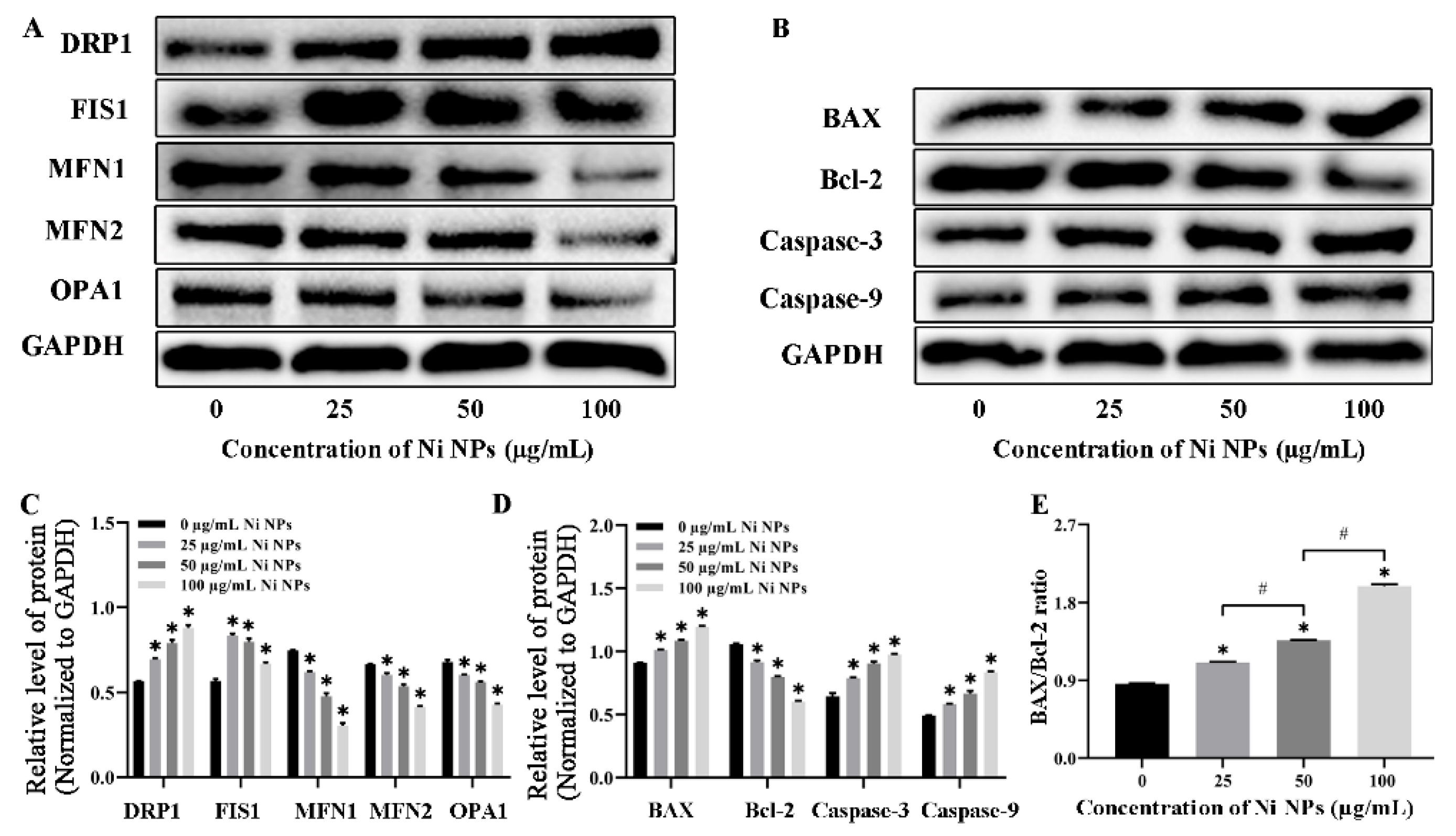

3.1.5. Effects of Ni NPs on the Expression of Mitochondria- and Apoptosis-Related Proteins

3.2. Regulation of Mitochondria by Mdivi-1 on the Reproductive Toxicity of Ni NPs

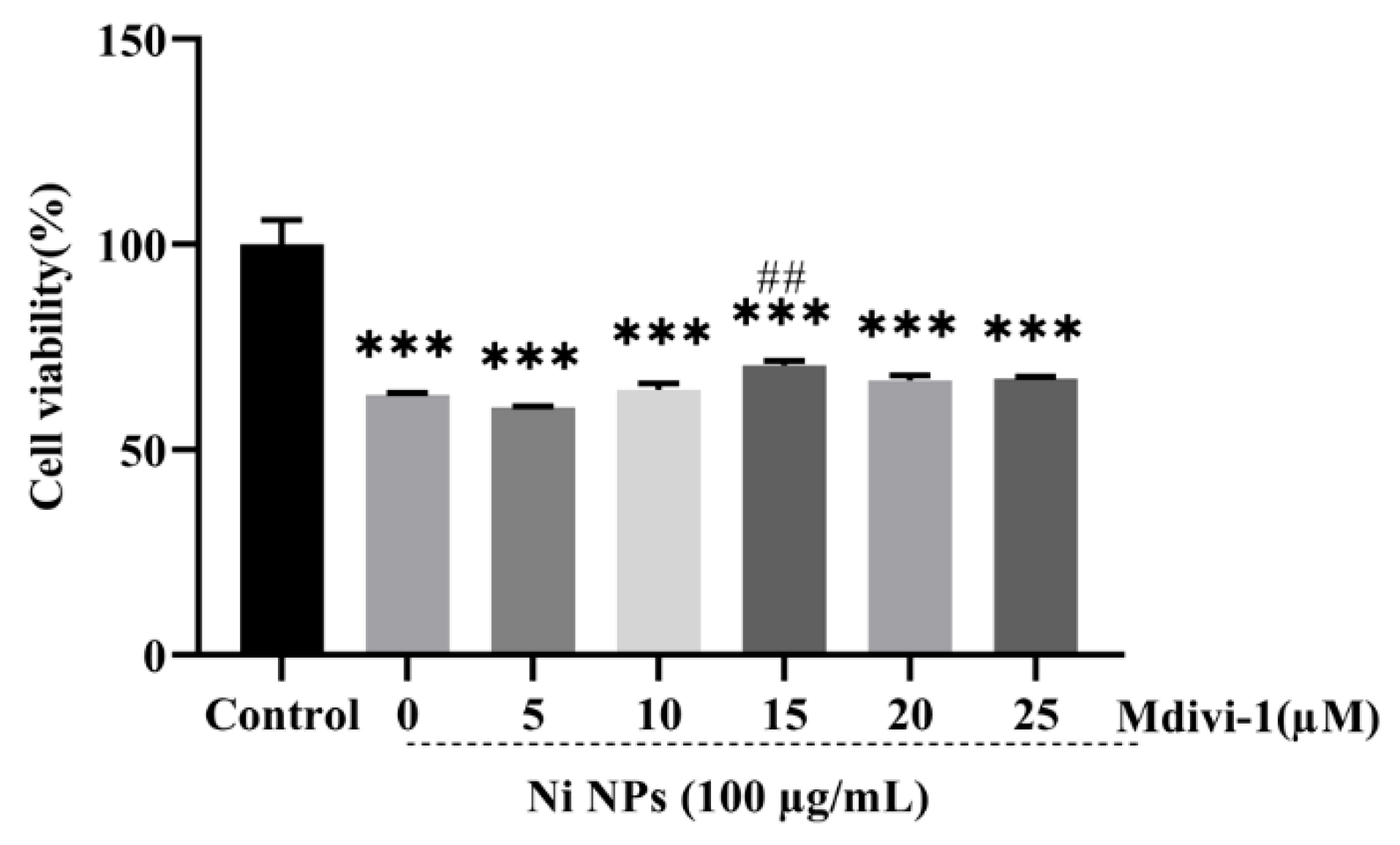

3.2.1. Determination of Optimal Conditions for Mdivi-1

3.2.2. Effect of Mdivi-1 on Cell Apoptosis Caused by Ni NPs

3.2.3. Effects of Mdivi-1 on Oxidative Stress Caused by Ni NPs

3.2.4. Effects of Mdivi-1 on Mitochondrial Structure and Function Caused by Ni NPs

3.2.5. Effects of Mdivi-1 on the Expression of Mitochondria- and Apoptosis-Related Proteins Caused by Ni NPs

3.3. Effects of Low Expression of Dnm1l on the Reproductive Toxicity of Ni NPs by Regulating Mitochondrial Division

3.3.1. Determination of Optimal Conditions for Dnm1l

3.3.2. Effects of Low Expression of Dnm1l on the Cytotoxicity Caused by Ni NPs

3.3.3. Effects of Low Expression of Dnm1l on Oxidative Stress Caused by Ni NPs

3.3.4. Effect of Low Expression of Dnm1l on the Ni NP-Induced Mitochondrial Structure and Function

3.3.5. Effects of Low Expression of Dnm1l on the Expression of Mitochondria- and Apoptosis-Related Proteins Caused by Ni NPs

4. Conclusions and Outlooks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, A.; Mulgund, A.; Hamada, A.; Chyatte, M.R. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, R.; D’Hauwers, K.; IntHout, J.; Braat, D.; Fleischer, K. Impact of a nutritional supplement (Impryl) on male fertility: Study protocol of a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (SUppleMent Male fERtility, SUMMER trial). BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, H.; Jorgensen, N.; Martino-Andrade, A.; Mendiola, J.; Weksler-Derri, D.; Mindlis, I.; Pinotti, R.; Swan, S.H. Temporal trends in sperm count: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakkebaek, N.E.; Rajpert-De Meyts, E.; Louis, G.M.B.; Toppari, J.; Andersson, A.M.; Eisenberg, M.L.; Jensen, T.K.; Jorgensen, N.; Swan, S.H.; Sapra, K.J.; et al. Male reproductive disorders and fertility trends: Influences of environment and genetic susceptibility. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 55–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Verma, Y.; Rana, S.V.S. Attributes of oxidative stress in the reproductive toxicity of nickel oxide nanoparticles in male rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 5703–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doreswamy, K.; Shrilatha, B.; Rajeshkumar, T.; Muralidhara. Nickel-induced oxidative stress in testis of mice: Evidence of DNA damage and genotoxic effects. J. Androl. 2004, 25, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.R.; Yang, Y.; Lou, Y.B.; Zuo, Z.C.; Cui, H.M.; Deng, H.D.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Fang, J. Apoptosis and DNA damage mediated by ROS involved in male reproductive toxicity in mice induced by Nickel. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 268, 115679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Rizvi, A.; Akhtar, K.; Khan, A.A.; Naseem, I. Nickel-induced oxidative stress causes cell death in testicles: Implications for male infertility. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirimer, L.; Thanh, N.T.; Loizidou, M.; Seifalian, A.M. Toxicology and clinical potential of nanoparticles. Nano Today 2011, 6, 585–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Mei, K.C.; Chang, C.H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Q.; Guiney, L.M.; Hersam, M.C.; Liao, Y.P.; et al. Lateral size of graphene oxide determines differential cellular uptake and cell death pathways in Kupffer cells, LSECs, and hepatocytes. Nano Today 2021, 37, 101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftis, J.B.; Miller, M.R. Nanoparticle translocation and multi-organ toxicity: A particularly small problem. Nano Today 2019, 26, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sree, B.K.; Kumar, N.; Singh, S. Reproductive toxicity perspectives of nanoparticles: An update. Toxicol. Res. 2024, 13, tfae077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.; Behnam, B.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Rezaee, R.; Abiri, A.; Ramezani, M.; Giesy, J.P.; Sahebkar, A. Reproductive Toxicity of Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2025, 32, 1507–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, L.B.; Miller, H.A.; Halwes, M.E.; Steinbach-Rankins, J.M.; Frieboes, H.B. Modeling of nanoparticle transport through the female reproductive tract for the treatment of infectious diseases. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 138, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Staden, D.; Gerber, M.; Lemmer, H.J.R. The Application of Nano Drug Delivery Systems in Female Upper Genital Tract Disorders. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.N.; Che, R.J.; Zong, X.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Li, J.N.; Zhang, C.F.; Wang, F.H. A comprehensive review on the source, ingestion route, attachment and toxicity of microplastics/nanoplastics in human systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 352, 120039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.X.; Xiao, K. Distribution and Biological Effects of Nanoparticles in the Reproductive System. Curr. Drug Metab. 2016, 17, 478–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamucho, A.; Unrine, J.M.; Kieran, T.J.; Glenn, T.C.; Schultz, C.L.; Farman, M.; Svendsen, C.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Tsyusko, O.V. Genomic mutations after multigenerational exposure of Caenorhabditis elegans to pristine and sulfidized silver nanoparticles. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Tang, M.; Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Hu, K.; Lu, W.; Wei, C.; Liang, G.; Pu, Y. Nickel nanoparticles exposure and reproductive toxicity in healthy adult rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 21253–21269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Taweel, G.M.; Albetran, H.M.; Al-Mutary, M.G.; Ahmad, M.; Low, I.M. Alleviation of silver nanoparticle-induced sexual behavior and testicular parameters dysfunction in male mice by yttrium oxide nanoparticles. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, N.; Instanes, C.; Sandberg, W.J.; Refsnes, M.; Schwarze, P.; Kruszewski, M.; Brunborg, G. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles in testicular cells. Toxicology 2012, 291, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, G.; Delaval, M.N.; Mukherjee, S.P.; Federico, A.; Khaliullin, T.O.; Yanamala, N.; Fatkhutdinova, L.M.; Kisin, E.R.; Greco, D.; Fadeel, B.; et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes elicit concordant changes in DNA methylation and gene expression following long-term pulmonary exposure in mice. Carbon 2021, 178, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.H.; El-Beih, N.M.; El-Hussieny, E.A.; El-Sayed, W.M. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Induced Testicular Toxicity Through Inflammation and Reducing Testosterone and Cell Viability in Adult Male Rats. Biol. TRACE Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 1934–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.I.L.; Roca, C.P.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. High-throughput transcriptomics: Insights into the pathways involved in (nano) nickel toxicity in a key invertebrate test species. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klostergaard, J.; Seeney, C.E. Magnetic nanovectors for drug delivery. Nanomedicine 2012, 8, S37–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.J.; Chen, T.C.; Lin, J.H.; Huang, P.R.; Tsai, H.J.; Chen, C.S. One-step preparation of hydrophilic carbon nanofiber containing magnetic Ni nanoparticles materials and their application in drug delivery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 440, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.A.E.; Salim, V.M.M.; Rodrigues, T.S. Controlled Nickel Nanoparticles: A Review on How Parameters of Synthesis Can Modulate Their Features and Properties. AppliedChem 2024, 4, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, N.; Darband, G.B. A review on electrodeposited metallic Ni-based alloy nanostructure for electrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 70, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.B.; Ye, B.R.; Li, C.; Tang, T.; Li, S.P.; Shi, S.J.; Wu, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.Q. Vertical Graphene-Supported NiMo Nanoparticles as Efficient Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction under Alkaline Conditions. Materials 2023, 16, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Hu, J.; Su, H.; Zhang, Q.X.; Sun, B.; Fan, L.S. Self-supported Ni2P nanoarrays as efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction and hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Lett. 2023, 351, 134998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiu, R.; Lan, M.J.; Chen, G.; Xu, W.; Shen, Y. Direct synthesis of binder-free Ni-Fe-S on Ni foam as superior electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 36556–36565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, T.; Zhang, L.Y.; Han, M.J.; Zhang, P.G.; Yang, D.L.; Xu, J.X.; Meng, X.J.; Zhu, Q.Y. Recent progress of Ni-based nanomaterials as promoter for enhancing the hydrogen evolution reaction performance of noble metal catalysts. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 998, 174896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagi, S.; Alfassam, H.E.; Saeedi, A.M.; Eldin, Z.E.; Ibrahim, E.M.M.; Shakor, A.B.A.; Abd El-Aal, M. A novel quercetin-loaded NiFe2O4@Liposomes hybrid biocompatible as a potential chemotherapy/hyperthermia agent and cytotoxic effects on breast cancer cells. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 91, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.R.; Prasad, E.; Fernandez, F.B.; Nishad, K.; Johnson, E.; Prema, K.H. Hyperthermia heating efficiency of glycine functionalised graphene oxide modified nickel nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 982, 173804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Tong, S.; Ma, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, T.B.; Wu, K.R.; Wu, J.Z. Nickel nanoparticles: A novel platform for cancer-targeted delivery and multimodal therapy. Front. Drug Deliv. 2025, 5, 1627556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, A.S.; Oyekunle, J.A.O.; Durodola, S.S.; Durosinmi, L.M.; Doherty, W.O.; Olayiwola, M.O.; Adegboyega, B.C.; Ajayeoba, T.A.; Akinyele, O.F.; Oluwafemi, O.S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes in Wastewater Using Solar Enhanced Nickel Oxide (NiO) Nanocatalysts Prepared by Chemical Methods. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 35, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Warsi, M.F.; Zulfiqar, S.; Sami, A.; Ullah, S.; Rasheed, A.; Alsafari, I.A.; Agboola, P.O.; Shakir, I.; Baig, M.M. Green nickel/nickel oxide nanoparticles for prospective antibacterial and environmental remediation applications. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 8331–8340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, M.D.B.; Bueno, J.D.P.; Rodríguez, C.H.; Pérez, A.X.M.; López, M.L.M.; Chacón, J.G.B.; López, C.M.; Robles, M.R.G.; Oza, G. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis using Electroless Deposition of Ni/NiO Nanoparticles on Silicon Nanowires for the Degradation of Methyl Orange. Curr. Nanosci. 2023, 19, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minisha, S.; Johnson, J.; Mohammad, S.; Gupta, J.K.; Aftab, S.; Alothman, A.A.; Lai, W.C. Visible Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Environmental Pollutants Using Zn-Doped NiO Nanoparticles. Water 2024, 16, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tailor, G.; Chaudhary, J.; Jandu, S.; Chetna; Mehta, C.; Yadav, M.; Verma, D. A Review on Green Route Synthesized Nickel Nanoparticles: Biological and Photo-catalytic Applications. Results Chem. 2023, 6, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Thakur, I.; Kumar, R. A review on synthesized NiO nanoparticles and their utilization for environmental remediation. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 172, 113758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Vitiello, V.; Casals, E.; Puntes, V.F.; Iamunno, F.; Pellegrini, D.; Changwen, W.; Benvenuto, G.; Buttino, I. Toxicity of nickel in the marine calanoid copepod Acartia tonsa: Nickel chloride versus nanoparticles. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 170, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.C.F.; Gomes, S.I.L.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Hazard assessment of nickel nanoparticles in soil-The use of a full life cycle test with Enchytraeus crypticus. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 2934–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanold, J.M.; Wang, J.; Brummer, F.; Siller, L. Metallic nickel nanoparticles and their effect on the embryonic development of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 212, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Boni, R.; Buttino, I.; Tosti, E. Spermiotoxicity of nickel nanoparticles in the marine invertebrate Ciona intestinalis (ascidians). Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Gao, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, T.; Xue, Y.; Tang, M. Reproductive toxicity induced by nickel nanoparticles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Hu, W.; Lu, C.; Cheng, K.; Tang, M. Mechanisms underlying nickel nanoparticle induced reproductive toxicity and chemo-protective effects of vitamin C in male rats. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.Y.; Su, L.; Sun, Y.F.; Han, A.J.; Chang, X.H.; Zhu, A.; Liu, F.F.; Li, J.; Sun, Y. Nickel sulfate induced apoptosis via activating ROS-dependent mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways in rat Leydig cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 1918–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.H.; Liu, F.F.; Tian, M.M.; Zhao, H.J.; Han, A.J.; Sun, Y.B. Nickel oxide nanoparticles induce hepatocyte apoptosis via activating endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways in rats. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 2492–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Verma, Y.; Rana, S.V.S. Higher Sensitivity of Rat Testes to Nano Nickel than Micro Nickel Particles: A Toxicological Evaluation. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 3521–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Hu, W.; Gao, X.; Wu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Cheng, K.; Tang, M. Molecular mechanisms underlying nickel nanoparticle induced rat Sertoli-germ cells apoptosis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 692, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, F.; Zeng, Y.; Zou, P.; An, H.; Chen, Q.; Ling, X.; Han, F.; Liu, W.; et al. BPDE and B[a]P induce mitochondrial compromise by ROS-mediated suppression of the SIRT1/TERT/PGC-1alpha pathway in spermatogenic cells both in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 376, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, W.; Jiang, F.; Zou, P.; Zeng, Y.; Ling, X.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, J.; Ao, L. PERK regulates Nrf2/ARE antioxidant pathway against dibutyl phthalate-induced mitochondrial damage and apoptosis dependent of reactive oxygen species in mouse spermatocyte-derived cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 308, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blajszczak, C.; Bonini, M.G. Mitochondria targeting by environmental stressors: Implications for redox cellular signaling. Toxicology 2017, 391, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, D.F.; Norris, K.L.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Shkurat, T.P.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhov, A.N. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease: A brief review. Ann. Med. 2018, 50, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhang, L.; Mo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Peng, Q.; Huang, L.; Ai, Y. Mdivi-1 attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting MAPKs, oxidative stress and apoptosis. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 62, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, M.; Zablocki, D.; Sadoshima, J. The role of Drp1 in mitophagy and cell death in the heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 142, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Dong, J.; Lu, W.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Tang, M. Exposure effects of inhaled nickel nanoparticles on the male reproductive system via mitochondria damage. NanoImpact 2021, 23, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Gao, X.; Zhu, J.; Cheng, K.; Tang, M. Mechanisms involved in reproductive toxicity caused by nickel nanoparticle in female rats. Environ. Toxicol. 2016, 31, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Wu, Y.; Hu, W.; Liu, L.; Xue, Y.; Liang, G. Mechanisms underlying reproductive toxicity induced by nickel nanoparticles identified by comprehensive gene expression analysis in GC-1 spg cells. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 275, 116556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Tang, M.; Kong, L. Effect and mechanism of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in the apoptosis of GC-1 cells induced by nickel nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2020, 255, 126913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lu, W.; Dong, J.; Wu, Y.; Tang, M.; Liang, G.; Kong, L. Study of the mechanism of mitochondrial division and mitochondrial autophagy in the male reproductive toxicity induced by nickel nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 1868–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Huang, T.; Zhang, W.; Zou, W.; Kuang, H.; Yang, B.; Wu, L.; Zhang, D. Perfluorooctanoic acid induces cytotoxicity in spermatogonial GC-1 cells. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, M.; Gan, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Yu, M.; Wei, J.; Chen, J. Involvement of oxidative stress in ZnO NPs-induced apoptosis and autophagy of mouse GC-1 spg cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 202, 110960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Parte, P. Revisiting the Characteristics of Testicular Germ Cell Lines GC-1(spg) and GC-2(spd)ts. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Liang, J.; Teng, Y.; Fu, J.; Miao, S.; Zong, S.; Wang, L. Nemo-like kinase promotes etoposide-induced apoptosis of male germ cell-derived GC-1 cells in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, K.; Schiavone, S.; Miller, F.J., Jr.; Krause, K.H. Reactive oxygen species: From health to disease. Swiss Med. Wkly 2012, 142, w13659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J. Physiol. 2003, 552, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 2977–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G.; Lamarche, F.; Cottet-Rousselle, C.; Hallakou-Bozec, S.; Borel, A.L.; Fontaine, E. The mechanism by which imeglimin inhibits gluconeogenesis in rat liver cells. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2021, 4, e00211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, J.; Peng, W.; Chen, X.; Kang, X.; Zeng, Q. UCP2 ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 71, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagkos, G.; Koufopoulos, K.; Piperi, C. A new model for mitochondrial membrane potential production and storage. Med. Hypotheses 2014, 83, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estaquier, J.; Vallette, F.; Vayssiere, J.L.; Mignotte, B. The mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 942, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brentnall, M.; Rodriguez-Menocal, L.; De Guevara, R.L.; Cepero, E.; Boise, L.H. Caspase-9, caspase-3 and caspase-7 have distinct roles during intrinsic apoptosis. BMC Cell. Biol. 2013, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.; Tait, S.W. Mitochondrial apoptosis: Killing cancer using the enemy within. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, Z.; Xia, J.; Qin, G.; Sang, N. Sulfur dioxide induces apoptosis via reactive oxygen species generation in rat cardiomyocytes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 8758–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.V.; Cabral, E.T.; Coroadinha, A.S. Progress and Perspectives in the Development of Lentiviral Vector Producer Cells. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 16, e2000017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; He, X.; Liu, F.; Jiang, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, J. Development and clinical translation of ex vivo gene therapy. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 2986–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, T.; Parker, N.; Yla-Herttuala, S. History of gene therapy. Gene 2013, 525, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milone, M.C.; O’Doherty, U. Clinical use of lentiviral vectors. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danno, S.; Itoh, K.; Baum, C.; Ostertag, W.; Ohnishi, N.; Kido, T.; Tomiwa, K.; Matsuda, T.; Fujita, J. Efficient gene transfer by hybrid retroviral vectors to murine spermatogenic cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 1819–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. MFN1 and MFN2 Are Dispensable for Sperm Development and Functions in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, M.; Chang, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; et al. MFN2 Plays a Distinct Role from MFN1 in Regulating Spermatogonial Differentiation. Stem Cell Rep. 2020, 14, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qiao, L.; Tong, Z.; Xu, Y.; Guan, C.; Liang, G.; Kong, L. Promoting Drp1-Mediated Mitochondrial Division in Nickel Nanoparticles-Induced Reproductive Toxicity in GC-2 Cells. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010034

Qiao L, Tong Z, Xu Y, Guan C, Liang G, Kong L. Promoting Drp1-Mediated Mitochondrial Division in Nickel Nanoparticles-Induced Reproductive Toxicity in GC-2 Cells. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiao, Liya, Zhimin Tong, Yabing Xu, Chunliu Guan, Geyu Liang, and Lu Kong. 2026. "Promoting Drp1-Mediated Mitochondrial Division in Nickel Nanoparticles-Induced Reproductive Toxicity in GC-2 Cells" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010034

APA StyleQiao, L., Tong, Z., Xu, Y., Guan, C., Liang, G., & Kong, L. (2026). Promoting Drp1-Mediated Mitochondrial Division in Nickel Nanoparticles-Induced Reproductive Toxicity in GC-2 Cells. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010034