Combustion-Synthesized BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ Triple-Co-Doped Long-Afterglow Phosphors: Luminescence and Anti-Counterfeiting Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment Content

2.1. Materials and Methods

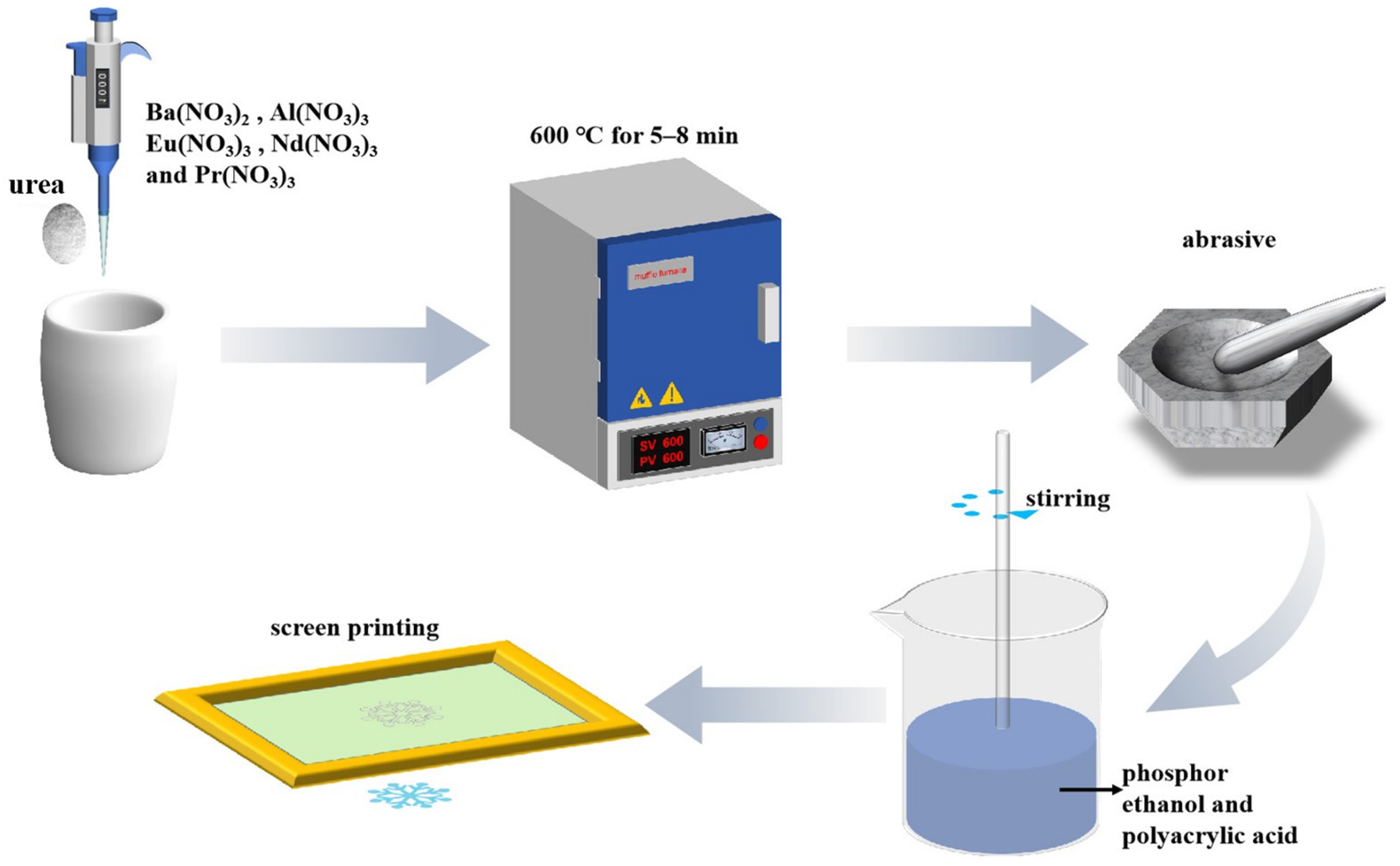

2.2. Material Synthesis

2.3. Preparation of Ink

2.4. Characterization of Materials

3. Results and Discussion

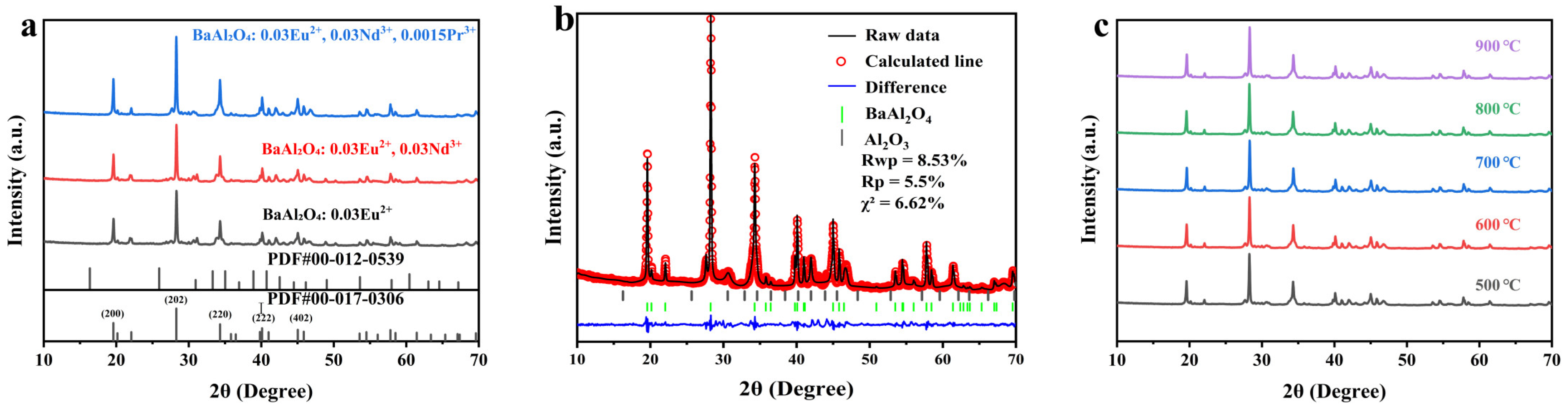

3.1. XRD Structural Analysis

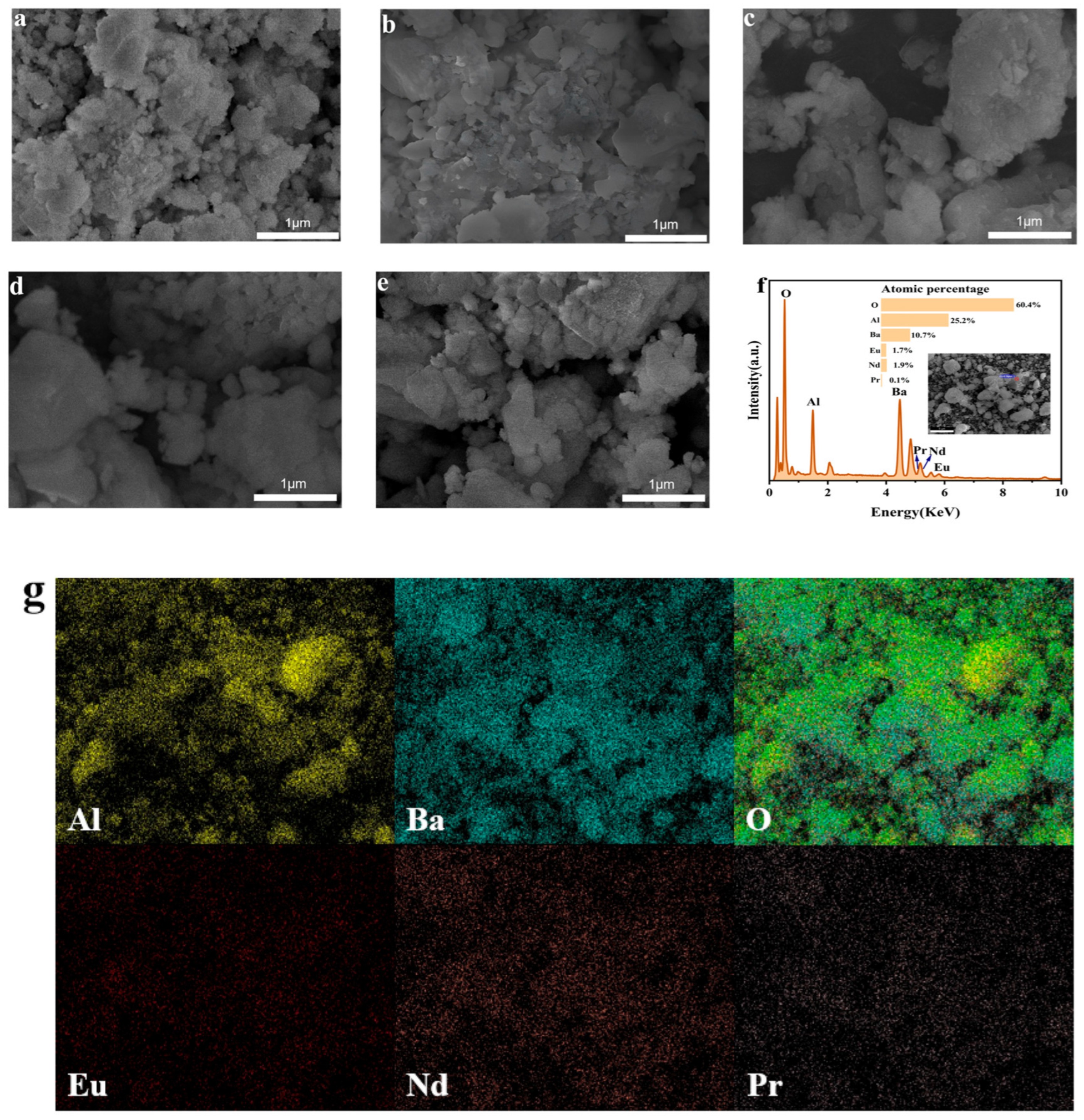

3.2. SEM Analysis

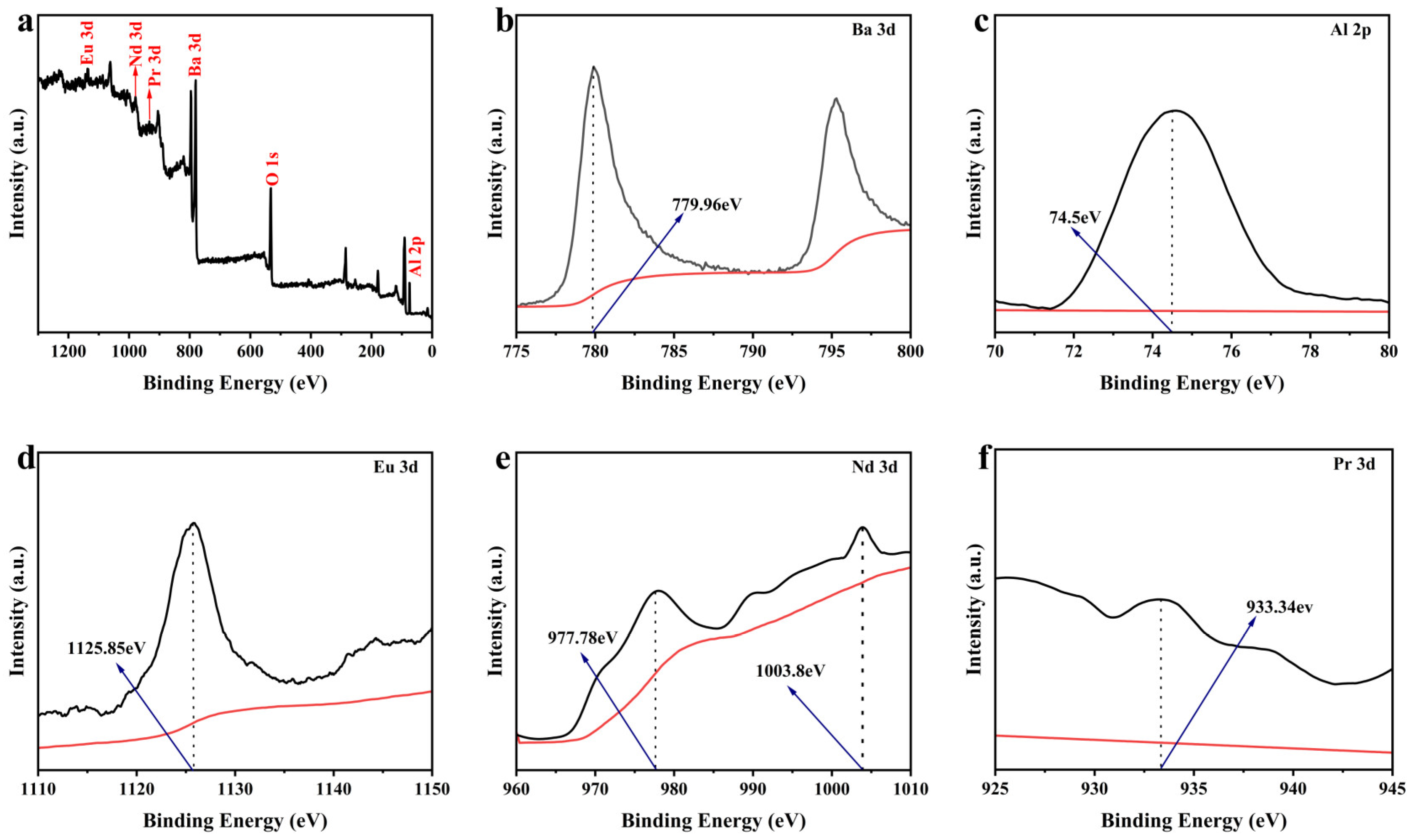

3.3. XPS Analysis

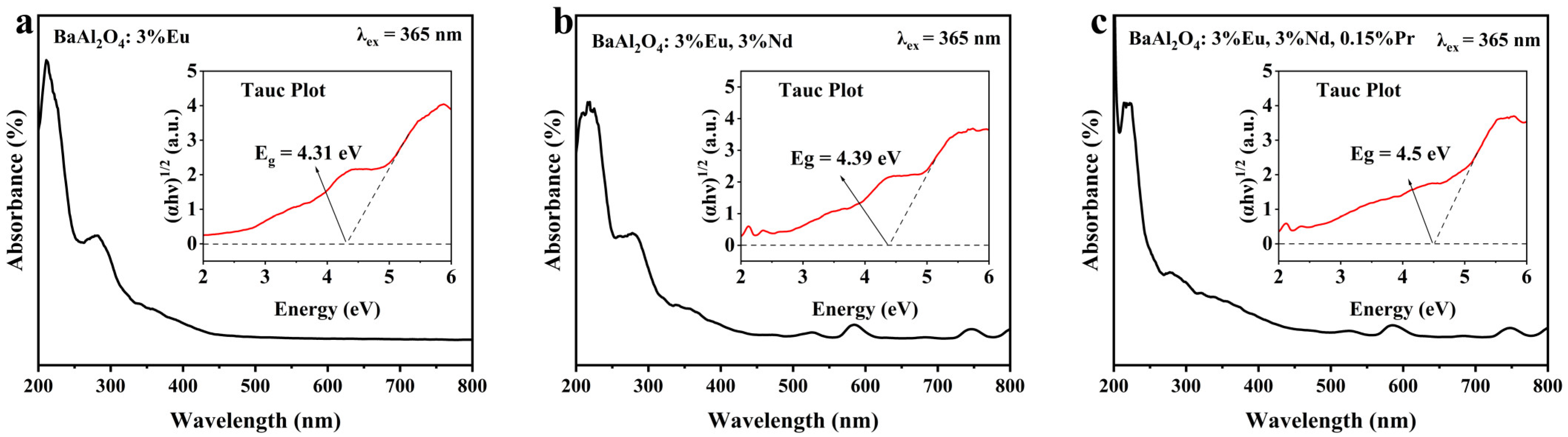

3.4. Ultraviolet Diffuse Reflectance Characterization

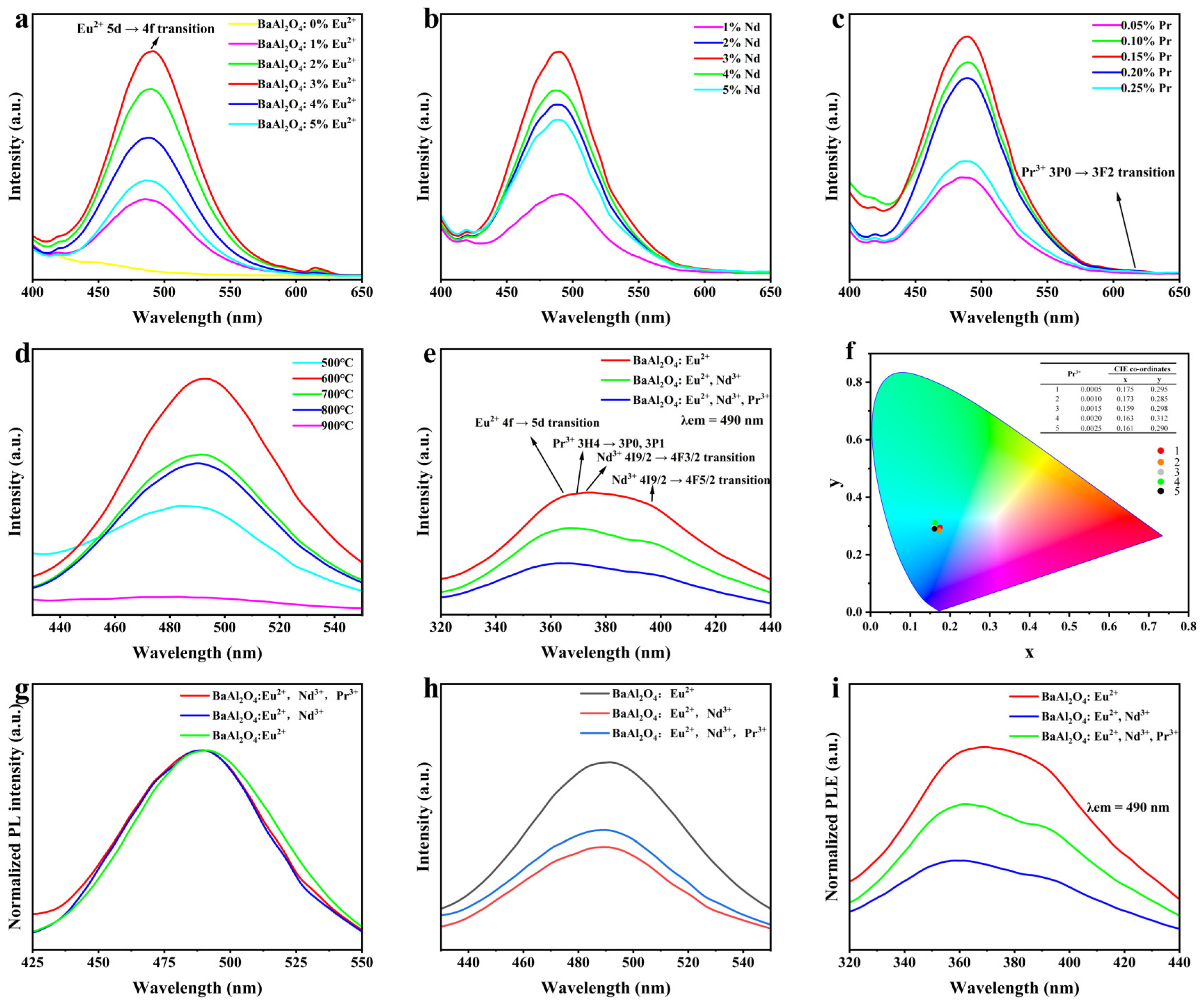

3.5. Photoluminescence Analysis

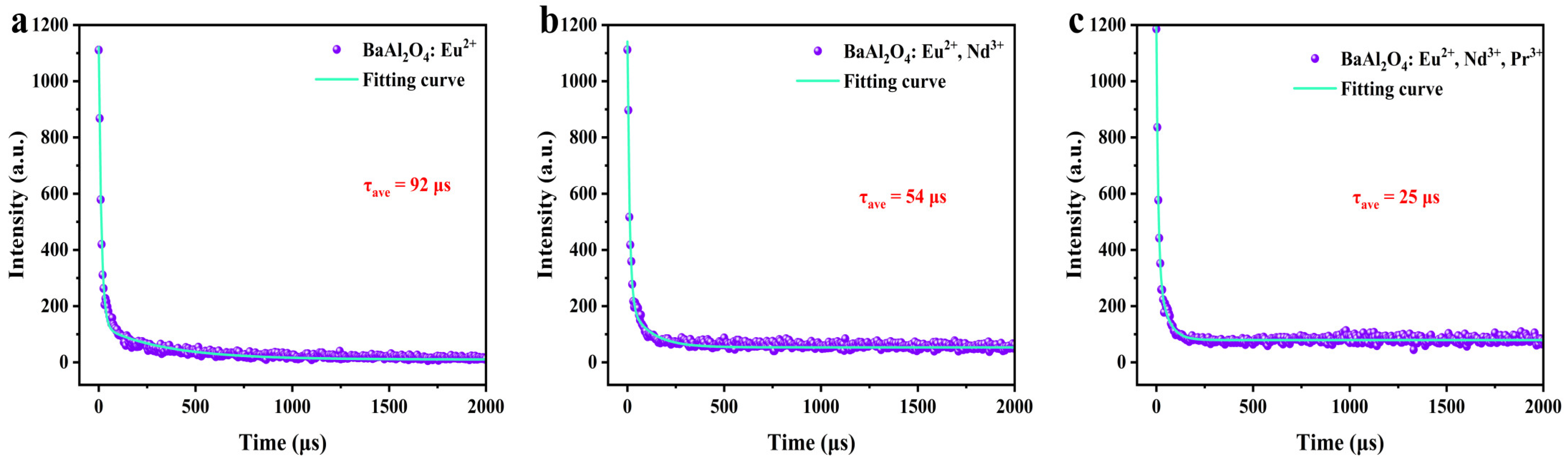

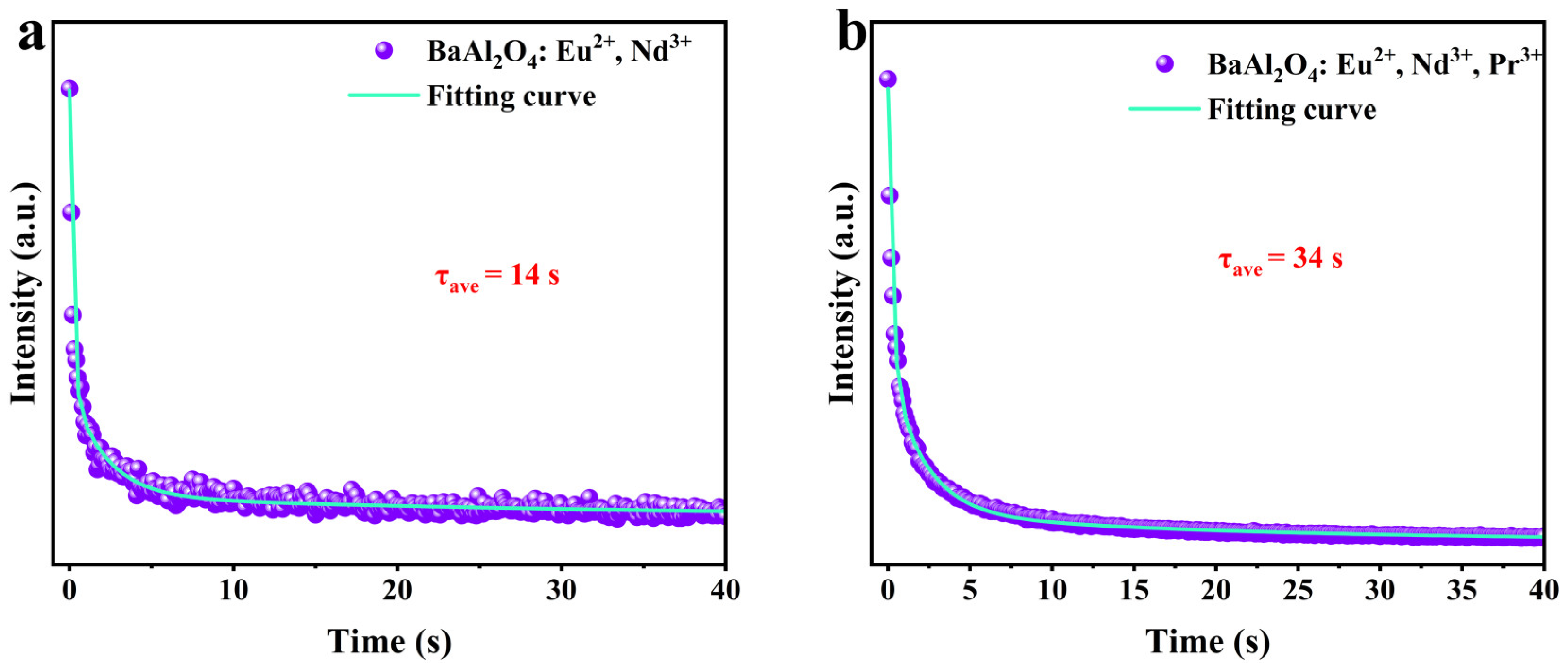

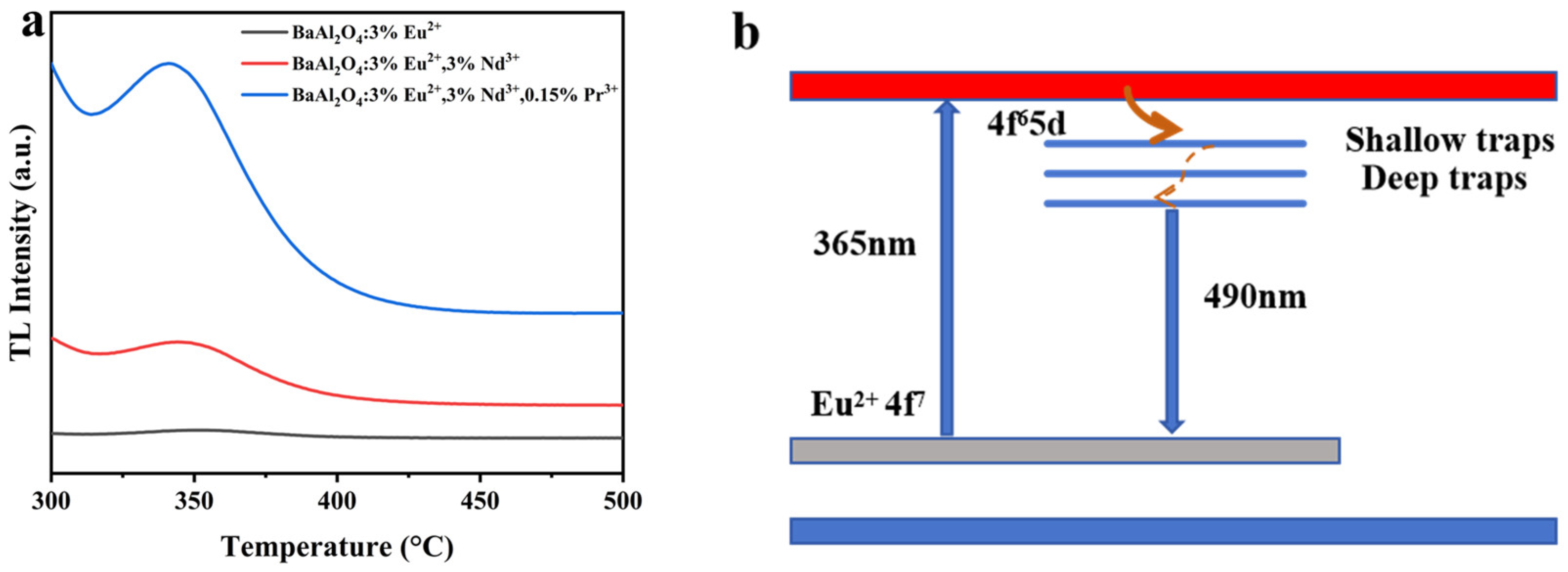

3.6. Fluorescence Lifetime and Afterglow Decay

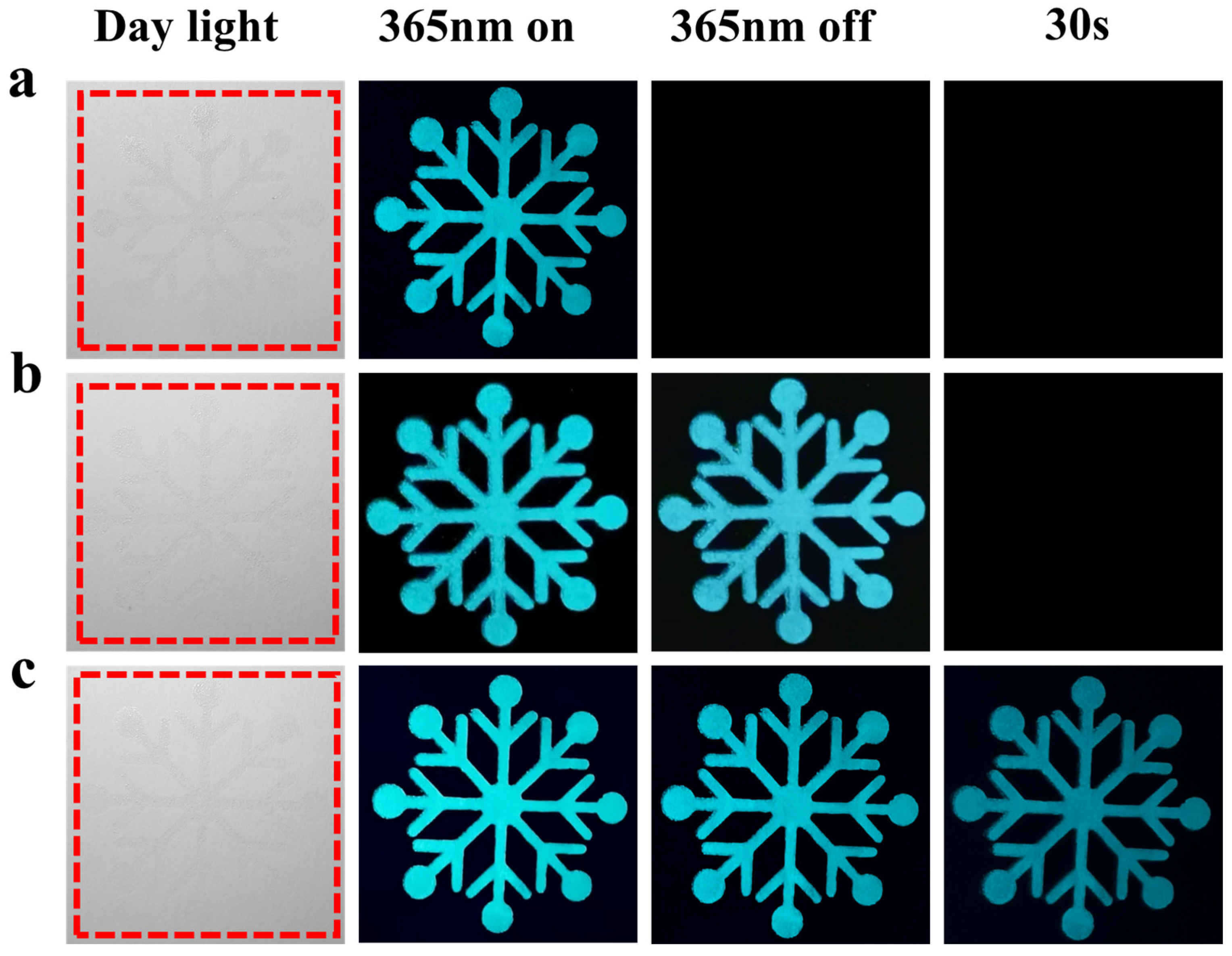

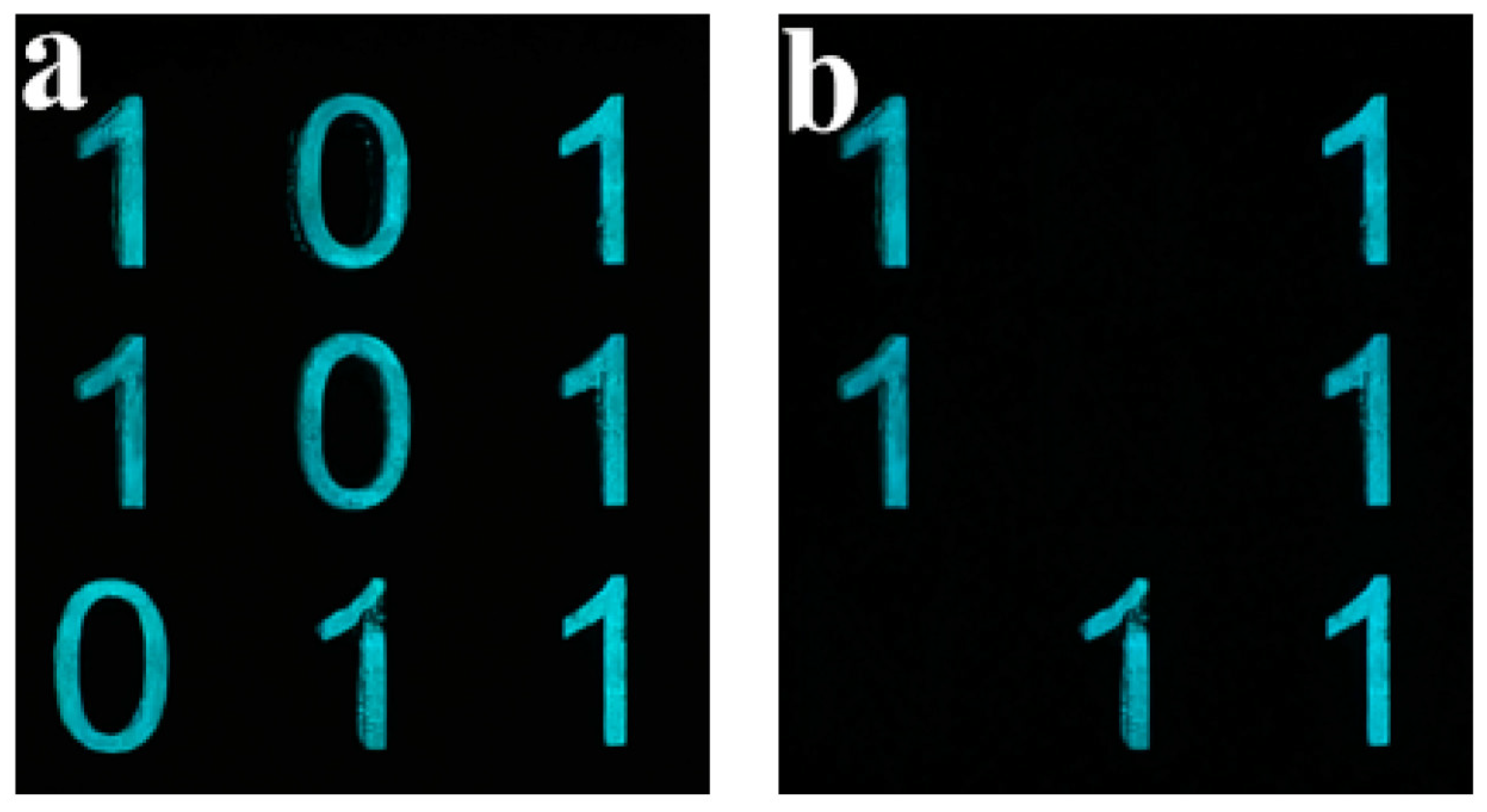

3.7. Anti-Counterfeiting Applications

3.8. Comparative Landscape and Application Positioning

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, L.; Gai, S.; Ding, H.; Yang, D.; Feng, L.; Yang, P. Recent Progress in Inorganic Afterglow Materials: Mechanisms, Persistent Luminescent Properties, Modulating Methods, and Bioimaging Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2023, 11, 2202382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Pradhan, P.; Priya, S.; Mund, S.; Vaidyanathan, S. Recent progress in trivalent europium (Eu3+)-based inorganic phosphors for solid-state lighting: An overview. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 13027–13057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakradhar, S.P.; Krushna, B.R.R.; Sharma, S.C.; George, A.; Manod, P.; Ponnazhagan, K.; Manjunatha, K.; Wu, S.Y.; Nagabhushana, H. Color-tunable silica-coated-carbon dot-encapsulated LaCaAl3O7:Eu3+ phosphor: Bridging advanced lighting and multimodal security applications. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 173, 106145. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Ding, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y. Unveiling the Potential of Sunlight-Driven Multifunctional Blue Long Persistent Luminescent Materials via Cutting-Edge Trap Modulation Strategies. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2023, 12, 2302011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Ge, W.; Tian, Y.; He, P.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, X. Realization of green emission in AlN: Eu2+ phosphors for LED and flexible anti-counterfeiting film applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T. Effect of mixing process on the luminescent properties of SrAl2O4: Eu2+, Dy3+ long afterglow phosphors. J. Rare Earths 2010, 28, 150–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, D. Charging curves and excitation spectrum of long persistent phosphor SrAl2O4: Eu2+, Dy3+. Opt. Mater. 2003, 22, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Liu, Q.; Wu, J.; Jing, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, T.; Wang, J.; Qi, Y.; Li, Z. Enhanced Fluorescence Characteristics of SrAl2O4: Eu2+, Dy3+ Phosphor by Co-Doping Gd3+ and Anti-Counterfeiting Application. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa, T.; Aoki, Y.; Takeuchi, N.; Murayama, Y. A New Long Phosphorescent Phosphor with High Brightness, SrAl2O4 : Eu2+ , Dy3+ . J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 143, 2670–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Q.; Gao, P.; Wang, J.; Qi, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Jiang, T. Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of a Novel Blue-Green Long Afterglow BaYAl3O7: Eu2+, Nd3+ Phosphor and Its Anti-Counterfeiting Application. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Khanna, A. Blue afterglow in Eu2+ doped CaAl2O4 by electron irradiation. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2022, 276, 115569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.-g.; Huang, Y.M. Blue afterglow of undoped CaAl2O4 nanocrystals. EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 2019, 127, 17001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hema, N.; Kumar, K.G.; Dhanalakshmi, M.A.; Abbas, M.; Kuppusamy, M. Impact of Dy3+ and Ce3+ ion doping on the photoluminescence, thermoluminescence, and electrochemical properties of strontium aluminate (SrAl2O4) and barium aluminate (BaAl2O4) phosphors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.-S.; Gong, M.-L.; Qiu, X.-Q.; Yang, D.-J.; Cheah, K.-W. A bluish green barium aluminate phosphor for PDP application. Mater. Lett. 2006, 60, 3217–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Arima, M.; Kanno, H. Luminescence of barium aluminate phosphors activated by Eu2+ and Dy3+. Opt. Mater. 2013, 35, 1947–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.; Castaing, V.; Lozano, G.; Míguez, H. Trap Depth Distribution Determines Afterglow Kinetics: A Local Model Applied to ZnGa2O4: Cr3+. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 9129–9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergen, Ö.B.; Arda, E. Electrical, optical and dielectric properties of polyvinylpyrrolidone/graphene nanoplatelet nanocomposites. Opt. Mater. 2023, 139, 113823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Nakamura, T.; Adachi, S. Abnormal photoluminescence phenomena in (Tb3+, Eu3+) codoped Ga2O3 phosphor. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 678, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Zhao, J. Blue-green BaAl2O4: Eu2+,Dy3+ phosphors synthesized via combustion synthesis method assisted by microwave irradiation. J. Rare Earths 2011, 29, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.U.; AlZubi, R.I.; Juwhari, H.K.; Mousa, Y.A.; Khan, Z.U.; Figueroa, S.J.A.; Hans, P. Advanced probing of Eu2+/Eu3+ photoemitter sites in BaAl2O4: Eu scintillators by synchrotron radiation X-ray excited optical luminescence probe. Opt. Mater. 2025, 162, 116937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiaei, S.M.; Dini, G.; Bahrami, A. Synthesis, crystal structure, optical and adsorption properties of BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Eu2+/ L3+ (L = Dy, Er, Sm, Gd, Nd, and Pr) phosphors. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 20243–20250. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, X. Nano CaO grain characteristics and growth model under calcination. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 175, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Manam, J.; Sharma, S.K. Composites of BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Dy3+/organic dye encapsulated in mesoporous silica as multicolor long persistent phosphors based on radiative energy transfer. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 5934–5941. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.; Das, A.; Kumar, V. Eu2+, Dy3+codoped SrAl2O4 nanocrystalline phosphor for latent fingerprint detection in forensic applications. Mater. Res. Express 2016, 3, 015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedekar, K.A.; Wankhede, S.P.; Moharil, S.V.; Belekar, R.M. d–f luminescence of Ce3+ and Eu2+ ions in BaAl2O4, SrAl2O4 and CaAl2O4 phosphors. J. Adv. Ceram. 2017, 6, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Ju, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X.; Gao, L.; Qiu, K.; Yin, L. Exploring a particle-size-reduction strategy of YAG:Ce phosphor via a chemical breakdown method. J. Rare Earths 2021, 39, 938–945. [Google Scholar]

- Ryou, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, D.H. Effect of various activation conditions on the low temperature NO adsorption performance of Pd/SSZ-13 passive NOx adsorber. Catal. Today 2019, 320, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Huang, M.; Xiang, B. Phytic acid-derived Co2P/N-doped carbon nanofibers as flexible free-standing anode for high performance lithium/sodium ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 846, 156256. [Google Scholar]

- Nenadović, M.; Knežević, S.; Ivanović, M.; Nenadović, S.; Kisić, D.; Popović, M.; Potočnik, J. Influence of Thermal Treatment on the Chemical and Structural Properties of Geopolymer Gels Doped with Nd2O3 and Sm2O3. Gels 2024, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbury, D.E.; Ritchie, N.W.M. Using the EDS Clues: Peak Fitting Residual Spectrum and Analytical Total. Microsc. Microanal. 2019, 25, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, D.N.G.; Philip, J. Review on surface-characterization applications of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS): Recent developments and challenges. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 12, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Kesler, V.G.; Kokh, A.E.; Pokrovsky, L.D. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study of β-BaB2O4 optical surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 223, 352–360. [Google Scholar]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Vinnik, D.A.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Gudkova, S.A.; Isaenko, L.I.; Jiang, X.; Pokrovsky, L.D.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Mashkovtseva, L.S.; Lin, Z. Flux Crystal Growth and the Electronic Structure of BaFe12O19 Hexaferrite. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 5114–5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.-W.; Park, T.-R.; Cheon, C.I.; Cho, N.I.; Kim, J.S. The enhancement of luminescence in Co-doped cubic Eu2O3 using Li+ and Al3+ ions. J. Lumin. 2011, 131, 2597–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, J.; Yu, J. Synthesis and luminescence properties of single-phase Ca2P2O7: Eu2+, Eu3+ phosphor with tunable red/blue emission. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 16384–16394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshak, A.H.; Alahmed, Z.A.; Bila, J.; Atuchin, V.V.; Bazarov, B.G.; Chimitova, O.D.; Molokeev, M.S.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Yelisseyev, A.P. Exploration of the Electronic Structure of Monoclinic α-Eu2(MoO4)3: DFT-Based Study and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 10559–10568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuchin, V.V.; Gavrilova, T.A.; Grivel, J.C.; Kesler, V.G. Electronic structure of layered titanate Nd2Ti2O7. Surf. Sci. 2008, 602, 3095–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felhi, H.; Smari, M.; Bajorek, A.; Nouri, K.; Dhahri, E.; Bessais, L. Controllable synthesis, XPS investigation and magnetic property of multiferroic BiMn2O5 system: The role of neodyme doping. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2019, 29, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, A.; Krishna Chandar, N.R.; Kandasamy, A.; Karl Chinnu, M.; Marimuthu, K.N.; Mohan Kumar, R.; Jayavel, R. Luminescence and electrochemical properties of rare earth (Gd, Nd) doped V2O5 nanostructures synthesized by a non-aqueous sol–gel route. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 21778–21785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjunan, K.; Babu, R.R. Visible light photocatalysis application of (1–x)(SnO2) − (x)(Pr2O3) composite thin films by laboratory spray pyrolysis method. Appl. Phys. A 2024, 130, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Caballero, A.; Porras-Vázquez, J.M.; dos Santos-Gómez, L.; Zamudio-García, J.; Infantes-Molina, A.; Canales-Vázquez, J.; Losilla, E.R.; Marrero-López, D. Structure and Mixed Proton–Electronic Conductivity in Pr and Nb-Substituted La5.4MoO12−δ Ceramics. Materials 2025, 18, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauc, J. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous Ge and Si. Mater. Res. Bull. 1968, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, L.; Parida, B.N.; Parida, R.K.; Padhee, R.; Mahapatra, A.K. Structural, optical dielectric and ferroelectric properties of double perovskite BaBiFeTiO6. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 146, 110102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorenbos, P. Energy of the first 4f7→4f65d transition of Eu2+ in inorganic compounds. J. Lumin. 2003, 104, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Huang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Molokeev, M.S.; Atuchin, V.V.; Fang, M.; Huang, S. New Yellow-Emitting Whitlockite-type Structure Sr1.75Ca1.25(PO4)2: Eu2+ Phosphor for Near-UV Pumped White Light-Emitting Devices. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 5129–5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Tanner, P.A. Origin of the green persistent luminescence of Eu-doped SrAl2O4from a multiconfigurationalab initiostudy of 4f7→ 4f65d1transitions. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 6637–6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S. Review—Photoluminescence Spectroscopy of Eu2+-Activated Phosphors: From Near-UV to Deep Red Luminescence. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 016002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Mohapatra, S.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Annapurna, K. Energy transfer mechanisms and non-radiative losses in Nd3+ doped phosphate laser glass: Dopant concentration effect study. Opt. Mater. 2023, 143, 114229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, P.; Liu, K.; Ju, Z.; Wei, R.; Liu, W. Achieving mechano-upconversion-downshifting-afterglow multimodal luminescence in Pr3+/Er3+ coactivated Ba2Ga2GeO7 for multidimensional anticounterfeiting. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 5240–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, X.L.; Swierk, J.R. Using Lifetime and Quenching Rate Constant to Determine Optimal Quencher Concentration. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 25532–25536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagoub, M.Y.A.; Swart, H.C.; Bergman, P.; Coetsee, E. Enhanced Pr3+ photoluminescence by energy transfer in SrF2: Eu2+, Pr3+ phosphor. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 025204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. Technical note: Usability evaluation of the modified CIE1976 Uniform-Chromaticity scale for assessing image quality of visual display monitors. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2003, 13, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorenbos, P. Absolute location of lanthanide energy levels and the performance of phosphors. J. Lumin. 2007, 122–123, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamioka, H.; Igarashi, A.; Watabe, K.; Beni, S.; Nanai, Y. Pr and Al doping effects on the red emission and long lasting afterglow in CaTiO3 single crystals. Opt. Mater. 2025, 159, 116663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zha, Y.; Chen, F.; Duan, Q.; Wu, J.; Han, J.; Wen, Y.; Qiu, J. Discovery of the Delocalized Nature of the High-Energy Excited-State 4f Electron of Eu(III): Spectroscopic Evidence and Applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, e01029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Deng, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W. Effect of Si on near-infrared long persistent phosphor Zn3Ga2Ge2−xSixO10: 2.5 %Cr3+. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 9067–9072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitasalo, T.; Hölsä, J.; Jungner, H.; Lastusaari, M.; Niittykoski, J. Thermoluminescence Study of Persistent Luminescence Materials: Eu2+- and R3+-Doped Calcium Aluminates, CaAl2O4: Eu2+,R3+. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 4589–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, K.; Ragiń, T.; Kochanowicz, M.; Miluski, P.; Dorosz, J.; Leśniak, M.; Dorosz, D.; Kuwik, M.; Pisarska, J.; Pisarski, W.; et al. Analysis of Excitation Energy Transfer in LaPO4 Nanophosphors Co-Doped with Eu3+/Nd3+ and Eu3+/Nd3+/Yb3+ Ions. Materials 2023, 16, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Li, B.; He, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, Q. Correlation of Structure, Tunable Colors, and Lifetimes of (Sr, Ca, Ba)Al2O4: Eu2+, Dy3+ Phosphors. Materials 2017, 10, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Liu, Y. Luminescence Properties of a Pb2+ Activated Long-Afterglow Phosphor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, G245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Han, Y.; Tian, D.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, S. MOF matrix doped with rare earth ions to realize ratiometric fluorescent sensing of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol: Synthesis, characterization and performance. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 286, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J.; Qi, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Wang, R. Study on the Luminescence Performance and Anti-Counterfeiting Application of Eu2+, Nd3+ Co-Doped SrAl2O4 Phosphor. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, F.; Liu, S.; Song, Z.; Liu, Q. An improved method to evaluate trap depth from thermoluminescence. J. Rare Earths 2025, 43, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitis, G.; Furetta, C. Non-empirical peak shape methods based on the physical model of the one trap one recombination center model. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2024, 212, 111463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, B.-g.; Huang, Y.M. Green photoluminescence and afterglow of Tb-doped SrAl2O4. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 52, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, F.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y. Enhanced afterglow performance of CaAl2O4:Eu2+, Nd3+ phosphors by co-doping Gd3+. J. Rare Earths 2021, 39, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakauchi, D.; Kato, T.; Kawaguchi, N.; Yanagida, T. Comparative studies on scintillation properties of Eu-doped CaAl2O4, SrAl2O4, and BaAl2O4 crystals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 62, 010607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.-G.; Huang, Y.-M. Green Afterglow of Undoped SrAl2O4. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Ion | Concentration Range (x, y, z) | Optimization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Eu2+ | x = 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05 | Optimized for maximum photoluminescence |

| Step 2 | Nd3+ | y = 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05 | Optimized for afterglow and emission properties |

| Step 3 | Pr3+ | z = 0.0005, 0.001, 0.0015, 0.0020, 0.0025 | Optimized for further enhancing afterglow performance |

| Temperature Range | Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ | 500–900 °C | After determining the optimal doping concentration, use this temperature range for sample synthesis at the optimum temperature. |

| 2θ (°) | hkl | Intensity (I) (a.u.) | FWHM (β) (°) | Lattice Spacing (d) (Å) | Crystallite Size (D) (nm) | Dislocation Density (δ) (m−2) | Micro Strain (ε) (Dimensionless) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.602 | 200 | 45 | 0.191 | 0.453 | 41.740 | 0.574 | 4.824 |

| 28.282 | 202 | 100 | 0.180 | 0.315 | 45.008 | 0.494 | 3.117 |

| 34.317 | 220 | 40 | 0.338 | 0.261 | 24.325 | 1.690 | 4.777 |

| 40.115 | 222 | 25 | 0.277 | 0.225 | 30.192 | 1.097 | 3.310 |

| 45.042 | 402 | 19 | 0.315 | 0.201 | 26.999 | 1.372 | 3.315 |

| Composition | EU (eV) | 95% CI (eV) | Fit Window (eV) | Points (n) | R2 | S = kT/EU (300 K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaAl2O4: Eu2+ | 0.656 | 0.643–0.669 | 3.71–4.01 | 25 | 0.9977 | 0.0394 |

| BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+ | 0.38 | 0.373–0.386 | 2.85–3.15 | 42 | 0.997 | 0.0681 |

| BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ | 0.491 | 0.485–0.497 | 2.79–3.09 | 43 | 0.9984 | 0.0527 |

| BaAl2O4 | Decay Lifetimes (μs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | τ1 | A2 | τ2 | τ* | |

| Eu2+ | 16,847 | 60 | 73 | 712 | 92 |

| Eu2+, Nd3+ | 15,046 | 10 | 32 | 480 | 54 |

| Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ | 15,880 | 10 | 10 | 500 | 25 |

| BaAl2O4 | Decay Lifetimes (s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | τ1 | A2 | τ2 | τ* | |

| Eu2+, Nd3+ | 2159 | 2 | 126 | 29 | 14 |

| Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ | 181 | 2 | 25 | 44 | 34 |

| Material | Doping Concentration | Fluorescence Lifetime (μs/ns) | Afterglow Decay Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BaAl2O4: Eu2+ | Eu2+ = 0.03 | 92 μs | 0 s |

| BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+ | Eu2+ = 0.03, Nd3+ = 0.03 | 54 μs | 14 s |

| BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ | Eu2+ = 0.03, Nd3+ = 0.03, Pr3+ = 0.0015 | 25 μs | 34 s |

| SrAl2O4: Eu2+ | Eu2+ = 0.02 | 404 ns | 0 s |

| SrAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+ | Eu2+ = 0.02, Nd3+ = 0.01 | 46 ns | 13 s |

| Host System | Representative Activators/Co-Dopants | Typical Synthesis Route & T | Dominant Emission (Qualitative) | Persistence Window (Qualitative) | Ink/Printing Compatibility | Application Notes/Positioning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaAl2O4 | Eu2+ (emitter); Nd3+/Pr3+ (trap engineering) | Combustion (this work): ~600 °C; also solid-state reported | Cyan/blue (Eu2+ 5d–4f) | Second scale (~14 s → ~34 s via co-doping) | High (fine powders, low-T processing, screen-print inks) | Time-gated; print-ready |

| SrAl2O4 | Eu2+ (emitter); Dy3+ (traps) | Solid-state, typically > 1200 °C; flux/atmosphere tuning common | Green (~520–530 nm) | Minutes–hours under optimized conditions | Moderate (higher-T process;) | Long-duration; signage |

| CaAl2O4 | Eu2+ (emitter); Nd3+/Dy3+ (traps) | Solid-state/combustion (composition- dependent) | Blue (~440–460 nm) | Minute-class in literature (composition- dependent) | Moderate (depends on particle) | Blue; tunable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Qi, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, H.; Lv, J.; Cheng, X.; Pan, D.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Combustion-Synthesized BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ Triple-Co-Doped Long-Afterglow Phosphors: Luminescence and Anti-Counterfeiting Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201578

Wang C, Wang J, Qi Y, Hu J, Li H, Lv J, Cheng X, Pan D, Li Z, Li J. Combustion-Synthesized BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ Triple-Co-Doped Long-Afterglow Phosphors: Luminescence and Anti-Counterfeiting Applications. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(20):1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201578

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chuanming, Jigang Wang, Yuansheng Qi, Jindi Hu, Haiming Li, Jianhui Lv, Xiaohan Cheng, Deyu Pan, Zhenjun Li, and Junming Li. 2025. "Combustion-Synthesized BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ Triple-Co-Doped Long-Afterglow Phosphors: Luminescence and Anti-Counterfeiting Applications" Nanomaterials 15, no. 20: 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201578

APA StyleWang, C., Wang, J., Qi, Y., Hu, J., Li, H., Lv, J., Cheng, X., Pan, D., Li, Z., & Li, J. (2025). Combustion-Synthesized BaAl2O4: Eu2+, Nd3+, Pr3+ Triple-Co-Doped Long-Afterglow Phosphors: Luminescence and Anti-Counterfeiting Applications. Nanomaterials, 15(20), 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201578