Abstract

Defect manipulation in metal oxide is of great importance in boosting catalytic performance for propane oxidation. Herein, a selective atom removal strategy was developed to construct a defective manganese oxide catalyst, which involved the partial etching of a Mg dopant in MnOx. The resulting MgMnOx-H catalysts exhibited superior low-temperature catalytic activity (T50 = 185 °C, T90 = 226 °C) with a propane conversion rate of 0.29 μmol·gcat.−1·h−1 for the propane oxidation reaction, which is 4.8 times that of pristine MnOx. Meanwhile, a robust hydrothermal stability was guaranteed at 250 °C for 30 h of reaction time. The comprehensive experimental characterizations revealed that the catalytic performance improvement was closely related to the defective structures including the abundant (metal and oxygen) vacancies, distorted crystals, valence imbalance, etc., which prominently weakened the Mn-O bond and stimulated the mobility of surface lattice oxygen, leading to the elevation in the intrinsic oxidation activity. This work exemplifies the significance of defect engineering for the promotion of the oxidation ability of metal oxide, which will be valuable for the further development of efficient non-noble metal catalysts for propane oxidation.

1. Introduction

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), primarily emitted from the transportation, chemistry, and energy industries, are the well-known detrimental air pollutants, severely endangering human health [1]. Meanwhile, VOCs can be converted into secondary pollutants, thus generating near-surface ozone, photochemical smog, PM2.5, etc., posing severe threats to the ecological environment [2]. To achieve an efficient VOC abatement, catalyst-aided oxidation at low temperature has been perceived to be one of the most advanced approaches [3,4]. Among VOCs, propane is typified as an ultra-stable light alkane and is often used as a probe molecule to screen high-performance VOC elimination catalysts [5]. Although noble metal catalysts show high catalytic performance, the high cost, scarcity, and inferior stability greatly limit their widespread application [6,7,8,9]. It is imperative to explore cost-effective and robust alternative non-precious metal catalysts [10,11,12,13,14].

Among them, transition metal oxides represented by manganese oxides (MnOx) are widely studied for propane oxidation due to their abundant availability, multiple valences, excellent redox properties, adjustable structures, etc. [15,16,17]. Particularly, there has been great research interest in amorphous MnOx due to their randomly arranged atomic structure and abundant coordination-unsaturated sites, which could promote reactant adsorption and facilitate oxygen mobility [18,19,20]. As reported in a previous work, the catalytic oxidation performance of MnOx heavily relies on their oxygen vacancies (Ov), which is responsible for the O2 trapping and transformation into active surface oxygen to enhance the intrinsic oxidation activity [21]. Meanwhile, engineering a high-valence Mn4+ of MnOx was also deemed to be vital for the benefit of alkane adsorption and activation [22].

A significant number of studies have been devoted to engineering defective MnOx catalysts for environmental catalysis application. For example, Liao et al. synthesized low-crystallinity MnOx catalysts through a simple pyrolysis method, demonstrating that the increase in surface defects such as oxygen vacancies (Ov) contributed to the enhancement in selective NO oxidation activity [23]. Dai et al. synthesized MnOx catalysts with high-index facets, via an ultrasound-assisted precipitation method, proposing that the steric effect between high-index facet catalysts with reactants could enhance toluene oxidation [24]. By far, heteroatom (with discrepant atomic radius and electronegativity to Mn atoms) doping in transition metal oxide has emerged as a decent way to induce crystal distortion and valence imbalance, endowing a profound defective structure and electronic state modulation [25,26,27,28]. For example, Xing et al. synthesized MnOx catalysts doped with varying amounts of Sb via the co-precipitation method. Sb doping was found to enhance the catalyst surface acidity, redox ability, and chemisorbed oxygen content, thereby improving catalytic activity for the removal of NO and toluene [29]. Zhao et al. constructed Ce-doped MnOx using a redox precipitation method, which demonstrated significantly increased Ov and active oxygens for efficient toluene oxidation [30]. Wang et al. unveiled the efficacy of Fe doping in MnOx for the stimulation of oxygen mobility and the increase in Mn4+ ratio to achieve efficient VOC oxidation [31]. Chen et al. developed a reflux strategy to prepare a Zr-doped amorphous MnOx catalyst, which displayed a remarkable redox property and augmented acidity, embodying an improved performance for the oxidation of chloride containing alkanes [32]. Moreover, the promoting effect of alkaline metal doping in MnOx has been successfully validated for toluene oxidation aided by the reinforcement of reducibility and CO2 desorption [33]. Despite the above endeavors, there is still a continuous demand for the structure manipulation of MnOx to advance the practical application in low-temperature VOC oxidation [17]. Based on the recognition of the importance of defect engineering by metal doping, a rational reasoning has been suggested regarding whether further structure tailoring could be achieved by selectively removing part of the dopant. Therefore, it is expected that the metal vacancies will be occupied, leading to local crystal defects, promoting Ov formation, and increasing Mn valences; this strategy, however, has not been explored for propane oxidation.

Herein, an advanced defect engineering approach was proposed by selectively removing the Mg atoms in the Mg-doped MnOx. The “Less is more” function was realized by Mg de-doping, prominently stimulating the catalytic oxidation activity of propane and hydrothermal stability. With systematic characterizations, the structure–performance co-relationship was established. This work may pave a new path for the manipulation of high-performance non-precious metal catalysts in the application of VOC oxidation.

2. Experiment

2.1. Materials

The following compounds were used: KMnO4 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Shanghai China), Mn(Ac)2·4H2O (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Shanghai China), Mg(Ac)2·4H2O (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Shanghai China) and HNO3 solution (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Shanghai China), respectively. All thechemicals used in this study are reagent grade with higher than 99.0% purity.

2.2. Catalyst Preparation

MgMnOx: Mg-doped MnOx was prepared via a co-precipitation procedure. Typically, 1.85 g of KMnO4 was dissolved in 100 mL of deionized (DI) water with vigorous stirring to form a homogeneous solution. Then, 4.3 g of Mn(Ac)2·4H2O and 0.188 g of Mg(Ac)2·4H2O were added into the solution under continuous stirring at room temperature for 4 h. The obtained products were collected by filtration and washed several times with DI water and ethanol. Finally, the solids were dried in oven at 100 °C for 12 h and calcined at 300 °C for 4 h in air to obtain MgMnOx. As a reference, MgMnOx with different Mg(Ac)2·4H2O amounts of 0.038 g, 0.188 g, and 0.376 g was prepared, corresponding to MgMnOx-1, MgMnOx-2, and MgMnOx-3.

MgMnOx-H: To partially remove the Mg dopant, 0.3 g of MgMnOx was treated in 150 mL of HNO3 solution (5 mol·L−1) with stirring for 5 h at room temperature, followed by filtration and washing several times, which was dried at 100 °C for 12 h. The obtained sample is denoted as MgMnOx-H. As a reference, MgMnOx was also prepared with different acid washing times (3 h, 5 h, 7 h) to produce MgMnOx-H-t (t = 3 h, 5 h, 7 h).

2.3. Catalysts Characterizations

Details regarding X-ray Diffraction (XRD) patterns, nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM), H2 Temperature-Programmed Reduction (H2-TPR), Raman Spectroscopy, X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR), Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP), and in situ Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (in situ DRIFTs) are provided in the Supplementary Information.

2.4. Catalytic Performance Evaluation

As the setup in Figure S1 schematically shows, propane oxidation was carried out in a fixed-bed reactor using a reactant containing 0.5 vol.% C3H8 and 10 vol.% O2, balanced with Ar. The weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) was set at 60,000 mL·g−1·h−1 controlled by an MFC (Mass Flow Controller). The reaction temperature was increased from room temperature to 400 °C with a heating rate of 2 °C·min−1. The products were in situ-tested by a gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan, GC-2014).

C3H8 conversion was acquired from the following formulas:

where [C3H8]in and [C3H8]out represent the inlet and outlet C3H8 concentrations, respectively.

To obtain information of the apparent activation energy (Ea), the reaction was controlled in the kinetic regime (C3H8 conversion under 10%). The equation below was used for the calculation of Ea by acquiring the slope:

where k is the reaction rate, T stands for the absolute temperature, and R represents the molar gas constant.

3. Results and Discussions

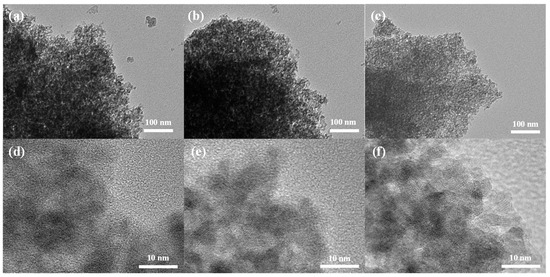

TEM and HR-TEM in Figure 1a,d show that MnOx has an overall amorphous structure with localized crystals in the framework. MgMnOx inherits the morphology of MnOx, but with a slightly looser structure (Figure 1b,e). The EDS elemental mapping (Figure S2a–d) shows that the Mg element is uniformly dispersed in MnOx, indicating that Mg atoms may be successfully doped in MnOx. MgMnOx was further etched by acid to enrich the defective structure. Compared with the MgMnOx sample, the MgMnOx-H sample (Figure 1c,f) shows a similar morphology, indicating that acid treatment did not destroy the whole texture. The Mg contents were determined to have decreased from 0.54 wt.% for MgMnOx to 0.17 wt.% for MgMnOx-H, as indicated by the ICP test. This demonstrates that the doped Mg atoms could be partially eliminated during the pickling process. Eventually, defect-rich MgMnOx-H was formed with the co-existence of metal vacancies derived from acid treatment as well as the remaining Mg dopant, which could also be indicated by the even distribution of Mg in the EDS elemental analysis in Figure S2e–h.

Figure 1.

(a–c) TEM and (d–f) HRTEM images of MnOx, MgMnOx, and MgMnOx-H.

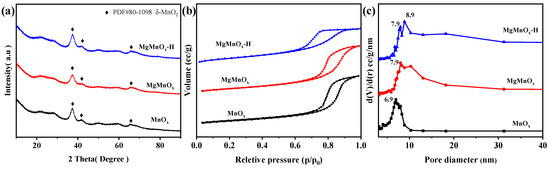

XRD was performed to explore the crystal phase of all catalysts, as shown in Figure 2a. It can be found that all catalysts display peaks at 25.3°, 37.0°, and 65.8°, assigned to birnessite-type MnO2 (δ-MnO2, JCPDS No. 80-1098). The broad and weak peaks indicate the poor crystallinity of all catalysts [34]. No Mg-related species are observed for MgMnOx and MgMnOx-H, indicating that Mg is doped into the lattice of MnOx without forming bulk Mg crystals. The N2 absorption–desorption isotherms in Figure 2b demonstrate a typical IV-type isotherm with an H2-type hysteresis loop, indicating the existence of abundant mesopores [35,36]. The mesoporous structure is further validated by the BJH pore size analysis (Figure 2c), which indicates that the mean pore size for MgMnOx-H is 7.9–8.9 nm, larger than those of MnOx (6.9 nm) and MgMnOx (7.9 nm). The specific surface area of MgMnOx-H is demonstrated to be 110.3 m2/g, smaller than those of MnOx (163.8 m2/g) and MgMnOx (126.8 m2/g) (Table 1), which may be due to the larger pore size in MgMnOx-H. Thus, the unique large mesopores of MgMnOx-H will be conducive to promoting mass transfer and alleviating the competitive adsorption of water molecules on active sites, thus benefitting the hydrothermal stability improvement.

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns, (b) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and (c) BJH pore-size distributions of MnOx, MgMnOx, and MgMnOx-H.

Table 1.

Pore structure and elemental information of the catalysts.

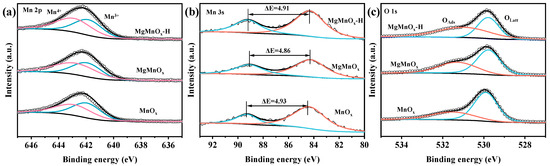

XPS analysis was employed to investigate the surface information of the catalyst. From Figure 3 and Table 1, it can be seen that Mn 2p3/2 XPS spectra can be deconvoluted into two peaks at 642.2 eV and 643.4 eV, corresponding to Mn3+ and Mn4+ species. As shown in Figure 3a and Table 1, the Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio of MgMnOx (1.21) is higher than that of MnOx (0.95). The increase in Mn valence state may be due to the partial substitution of divalent Mg for trivalent Mn ions. The Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio of MgMnOx-H (1.12) slightly decreases after acid etching but is still higher than that of the original MnOx. Furthermore, Mn 3s XPS spectra (Figure 3b) were deconvoluted to shed light on the AOS of Mn. As shown in Table 1, the AOS values for MnOx, MgMnOx, and MgMnOx-H are 3.40, 3.48, and 3.43, respectively. The change in AOS variation coincides with the trend of Mn4+/Mn3+ ratio variation. In addition, the O 1s spectra (Figure 3c) were fitted to two peaks at 529.8 eV and 531.5 eV, assigned to surface lattice oxygen (Olatt) and surface adsorbed oxygen (Oads) species, respectively [37,38]. Interestingly, the Oads/Olatt ratio of MgMnOx (0.40) increases after doping Mg in MnOx (0.32), indicating that the partial substitution of Mg for Mn ions generates more surface Ov. Furthermore, the Oads/Olatt ratio of MgMnOx-H (0.57) continues to increase after acid etching. This indicates that the partial de-doping of Mg further induces the formation of more Ov, which renders the gas-phase O2 easy to activate and convert to Oads, facilitating the deep oxidation of VOCs [39,40].

Figure 3.

Deconvolution of (a) Mn 2p, (b) Mn 3s, and (c) O 1s XPS spectra of MnOx, MgMnOx, and MgMnOx-H.

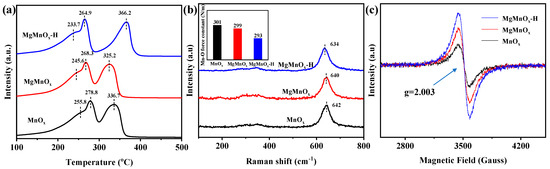

The reducibility of the metal oxide catalysts is closely associated with the mobility of surface reactive oxygen species and can be characterized by the H2-TPR. As shown in Figure 4a, two main reduction peaks at 260–300 °C and 300–400 °C can be clearly observed in all catalysts, corresponding to the sequential reduction of MnO2→Mn3O4→MnO [41]. By comparison, the low-temperature reduction peak follows MgMnOx-H (233.7 °C) < MgMnOx (245.6 °C) < MnOx (255.8 °C). This indicates that low-temperature oxygen mobility is improved after Mg doping and is further enhanced by the subsequent Mg de-doping. Raman spectra in Figure 4b show the peaks at 640 cm−1 and 350 cm−1, corresponding to the symmetrical vibration peak A1g (vs) of the Mn-O bond and the Eg vibrational peaks of the asymmetric stretching of Mn-O-Mn [42]. A distinct Raman peak deviation is evidenced for MgMnOx-H compared with MgMnOx and MnOx. This prominently suggests that more crystal defects (lattice compression, crystal distortion, etc.) are incubated for the acid-treated sample. Moreover, the force constant (k) of the surface Mn-O bond could be calculated based on Hooke’s law by the following equation [32,43]:

where ω is the Raman shift (cm−1), c is the speed of light, and μ is the effective mass of the Mn-O bond. As illustrated in the inset of Figure 4b, the force constant k of MgMnOx-H (293 N/m) is smaller than those of MgMnOx (299 N/m) and MnOx (301 N/m), implying that Mn-O could be greatly activated to engender a weaker Mn-O bond strength, which could facilitate Ov formation. The defect structures of the MnOx, MgMnOx, and MgMnOx-H catalysts were further measured using the EPR technique. As shown in Figure 4c, all the catalysts present a distinct feature at g = 2.003, stemming from the Ov filling with active oxygen species (i.e., O2− and O−) [44,45]. Obviously, the MgMnOx-H catalysts possess prominently more defective Ov than those in MnOx and MgMnOx catalysts. This reflects its superior redox ability of MgMnOx-H catalysts, which agrees well with the above H2-TPR and Raman results.

Figure 4.

(a) H2-TPR, (b) Raman spectra, and (c) EPR spectra of MnOx, MgMnOx, and MgMnOx-H.

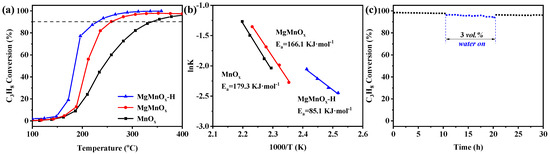

For the catalytic application in propane oxidation, the influence of Mg dopant amount was first scrutinized. As shown in Figure S3, the Mg doping amount follows a volcanic curve with catalytic performance, with MgMnOx-2 exhibiting the highest propane oxidation activity. It is speculated that excessive Mg could form MgO on the surface of MnOx, thereby covering part of the active sites, resulting in activity deterioration. Meanwhile, by changing the acid etching time, it was found that the MgMnOx treated by acid for 5 h has the highest activity (Figure S4). Too long an acid pickling time may result in a pore structure collapse and specific surface area reduction, leading to a decrease in the catalytic performance. The optimized MgMnOx-H was compared with MnOx and MgMnOx for propane oxidation, with the result shown in Figure 5a, and detailed activity data are illustrated in Table 2. Among them, the MgMnOx-H catalyst displays the best catalytic activity with a remarkably lower T50 (temperature for conversion of 50% propane) of 185 °C compared to those of the MnOx and MgMnOx catalysts (T50 = 242 and 208 °C, respectively). Meanwhile, the reaction rate of the MgMnOx-H catalyst was calculated to be 0.29 μmol·gcat.−1·s−1, 2.8 and 4.8 times those of MgMnOx (0.10 μmol·gcat.−1·s−1) and MnOx (0.06 μmol·gcat.−1·s−1) at 195 °C, respectively. Moreover, by evaluating Ea (Figure 5b) in the kinetic range (with propane conversion lower than 10%), it can be evidenced that MgMnOx-H has an Ea of 85.1 kJ·mol−1, significantly lower than those of MgMnOx (166.1 kJ·mol−1) and MnOx (179.3 kJ·mol−1). This sufficiently proves the excellent propane activation capacity of MgMnOx-H in achieving a superior propane oxidation activity. To investigate the influence of acid treatment, the pristine MnOx was also etched by the acid with a similar condition to that of MgMnOx-H. It can be seen from Figure S5 that MnOx-H shows a slight activity improvement with T50 reduced from 242 °C to 224 °C, which is, however, still obviously inferior to that of MgMnOx-H. This result strongly proves that the activity improvement for MgMnOx-H is more likely derived from the process of Mg atom de-doping.

Figure 5.

(a) Catalytic performance; (b) Arrhenius plots over MnOx, MgMnOx, and MgMnOx-H; and (c) hydrothermal stability test of MgMnOx-H catalysts at 250 °C (reaction conditions: 0.5 vol.% C3H8, 10 vol.% O2, Ar as balance gas, GHSV = 60,000 mL·g−1·h−1).

Table 2.

Catalytic activities, reaction rate at 195 °C, and apparent activation energy (Ea) of MnOx, MgMnOx, and MgMnOx-H catalysts.

Hydrothermal stability is another important factor in practical application. As shown in Figure 5c and Figure S6, both MnOx and MgMnOx demonstrate excellent stabilities under dry conditions, experiencing only a 5% and 4% decrease, respectively, in the first ten hours. However, when water was introduced, a more profound activity deterioration was evidenced with propane conversion decreasing by 11% and 8% for MnOx and MgMnOx, respectively. Once the water was cut off, the conversion could almost be recovered. Remarkably, it is observed that MgMnOx-H maintains an almost unchanged 97% propane conversion under dry conditions. The introduction of 3 vol.% H2O causes a slight decrease in propane conversion from 97% to 95% over an additional 10 h of reaction time. Once the water vapor is removed, the propane conversion swiftly rebounds to 96%, showcasing stable performance throughout another 10 h of testing. The higher hydrothermal stability for MgMnOx-H could be possibly attributed to the unique large mesopores, which will be conducive to promoting the mass transfer and alleviating the competitive adsorption of water molecules on active sites, thus benefitting steam resistance. These findings highlight the exceptional hydrothermal stability of MgMnOx-H, indicating its potential for applications requiring resilience to moisture.

The temperature-resolved in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (in situ DRIFTS) spectra of MnOx, MgMnOx and MgMnOx-H catalysts were measured to analyze the catalytic reaction mechanism of propane oxidation. As shown in Figure S7, the peaks at 2850–3020 cm−1 can be identified, assigned to the stretching vibration of CH3 and CH2 of adsorbed propane [43]. The peaks at 1441 cm−1, 1530 cm−1, and 1724 cm−1 can be attributed to the vibrational vibrations of υs(C=O), υs(COO), and υs(CH3COO). The peaks at 1131 cm−1, 1196 cm−1, and 1342 cm−1 belong to υ(C-O-CH), υas(C-O), and υ(C-O-C) vibrations, separately [46]. In addition, υas(C=C) is also observed at 1429 cm−1, indicating that olefin is one of the transition intermediates. All the catalysts show similar reaction pathways, indicating that the propane oxidation follows similar reaction mechanisms. This shows that the oxidation of propane on manganese dioxide can be divided into three steps. Firstly, propane adsorbs onto the catalyst surface, followed by catalytic oxidation to form propanone or propene species. Subsequently, the intermediates decompose into formic acid or acetic acid, ultimately resulting in the formation of products CO2 and H2O. Generally, the conversion of propane to propylene has a low reaction energy barrier in the early stage of the reaction [47], which is favorable for the catalytic combustion of propane. MgMnOx-H delivered a more rapid decrease in carbonate carboxylate and olefin with the rise in temperature, which proves its higher lattice oxygen activity, accelerating the conversion of intermediates and improving the catalytic combustion performance of propane. Based on the catalyst characterizations, we can infer that the high catalytic performance could be closely related to the weakened Mn-O bond in MgMnOx-H, which remarkably promoted the Ov formation and strengthened the active oxygen mobility. Meanwhile, the increase in ratio of high-valence Mn4+ could also be responsible for the enhancement in propane adsorption and the following activation. Moreover, the larger mesoporous structure in MgMnOx-H plays an important function in facilitating mass transfer, avoiding the H2O coverage on the active sites and therefore ensuring an excellent hydrothermal stability.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we proposed a doping and partial de-doping strategy to obtain defective MgMnOx-H catalysts, which shows a superior low-temperature catalytic activity and excellent hydrothermal stability towards propane oxidation. The high catalytic performance could be due to the beneficial structures in the MgMnOx-H catalyst including activated Mn-O bonds, augmented oxygen vacancies, boosted active oxygen sites, enhanced oxygen mobility, higher Mn4+ ratios, and larger mesoporous textures. The facile defect engineering in this work will be valuable in guiding the upgrade in the catalyst for advanced VOC oxidation reactions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nano14110907/s1, Text S1 Catalysts characterizations; Figure S1: Set-up diagram of propane catalytic oxidation.; Figure S2. (a,e) SEM image and EDS elemental mapping (b,f) O, (c,g) Mn and (d,h) Mg of MgMnOx and MgMnOx-H.; Figure S3. Catalytic performance of MnOx, MgMnOx-1, MgMnOx-2 and MgMnOx-3.; Figure S4. Catalytic performance of MgMnOx, MgMnOx-3h, MgMnOx-5h, MgMnOx-7h.; Figure S5. Catalytic performance of MnOx and MnOx-H.; Figure S6. Hydrothermal stability test of (a) MnOx and (b) MgMnOx at temperature corresponding to propane conversion above 90% (Reaction conditions: 0.5 vol.% C3H8, 10 vol.% O2, Ar as balance gas, GHSV = 60,000 mL·g−1·h−1).; Figure S7. In-situ DRIFTS spectra of propane oxidation (0.5% C3H8, 10% O2, balanced with N2) on (a) MnOx, (b) MgMnOx and (c) MgMnOx-H.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.X.; Validation, L.Z.; Formal analysis, L.L.; Investigation, H.D., H.B. and X.L.; Resources, S.C.; Writing—original draft, W.X.; Writing—review & editing, X.L. and H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22072069), the Open Project Program of Chemical Synthesis and Pollution Control Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (CSPC202110) and the Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Coal Combustion (FSKLCCA2110).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lu, Z.; Guo, L.; Shen, Q.; Bi, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. The Application of Metal–Organic Frameworks and Their Derivatives in the Catalytic Oxidation of Typical Gaseous Pollutants: Recent Progress and Perspective. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 340, 126772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Zhu, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, W.; Xu, S.; Lin, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, M.; Guo, L. Anionic Defects Engineering of Co3O4 Catalyst for Toluene Oxidation. Fuel 2022, 314, 122774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Román, E.J.; Can, F.; Meille, V.; Guilhaume, N.; González-Cobos, J.; Gil, S. MnOx Catalysts Supported on SBA-15 and MCM-41 Silicas for a Competitive VOCs Mixture Oxidation: In-Situ DRIFTS Investigations. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 344, 123613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Su, H.; Hu, Y.; Gong, C.; Lu, J.; He, D.; Zhu, W.; Chen, D.; Cao, X.; Li, J.; et al. Highly Efficient Degradation of Sulfur-Containing Volatile Organic Compounds by Amorphous MnO2 at Room Temperature: Implications for Controlling Odor Pollutants. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 334, 122877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Wei, J.; Gao, B.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X. New Insight into the Antagonism Mechanism between Binary VOCs during Their Degradation over Pd/ZrO2 Catalysts. ACS EST Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezkrovnyi, O.; Vorokhta, M.; Pawlyta, M.; Ptak, M.; Piliai, L.; Xie, X.; Dinhová, T.N.; Khalakhan, I.; Matolínová, I.; Kepinski, L. In Situ Observation of Highly Oxidized Ru Species in Ru/CeO2 Catalyst under Propane Oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 16675–16684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, G.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, A.; Cao, H.; Zhang, C. Catalytic Oxidation of Propane over Nanorod-like TiO2 Supported Ru Catalysts: Structure-Activity Dependence and Mechanistic Insights. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ding, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Song, P.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhan, W. Highly Efficient Oxidation of Propane at Low Temperature over a Pt-Based Catalyst by Optimization Support. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 17278–17287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, T.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, B.; Tang, Q.; Cao, Q.; Fang, W. Synergistic Catalysis in Loaded PtRu Alloy Nanoparticles to Boost Base-Free Aerobic Oxidation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural. Mater. Today Catal. 2023, 3, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; He, D.; Deng, W.; Jin, G.; Li, K.; Luo, Y. Illustrating New Understanding of Adsorbed Water on Silica for Inducing Tetrahedral Cobalt(II) for Propane Dehydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, B.; Shakoor, N.; Adeel, M.; Zhang, P.; Huang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, Y.; Rui, Y. Catalytic Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds by Non-Noble Metal Catalyst: Current Advancement and Future Prospectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Aghamohammadi, S.; Li, D.; Li, K.; Farrauto, R. Structure Dependence of Nb2O5-X Supported Manganese Oxide for Catalytic Oxidation of Propane: Enhanced Oxidation Activity for MnOx on a Low Surface Area Nb2O5-X. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 244, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wen, M.; Li, G.; An, T. Recent Advances in VOC Elimination by Catalytic Oxidation Technology onto Various Nanoparticles Catalysts: A Critical Review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 281, 119447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; He, K.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, G.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Hao, Z. Defect Enhanced CoMnNiOx Catalysts Derived from Spent Ternary Lithium-Ion Batteries for Low-Temperature Propane Oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 309, 121231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Feng, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Yuan, L.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X. Mn-Based Catalysts Derived from the Non-Thermal Treatment of Mn-MIL-100 to Enhance Its Water-Resistance for Toluene Oxidation: Mechanism Study. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Shen, Y.; Liu, B.; Ji, J.; Dai, W.; Huang, P.; Zhang, D.; Li, G.; Xie, R.; Huang, H. Boosting Ozone Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene at Room Temperature by Using Hydroxyl-Mediated MnOx/Al2O3 Catalysts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7041–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, G.; Sun, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Ma, C.; Hao, Z. The Positive Effect of Water on Acetaldehyde Oxidation Depended on the Reaction Temperature and MnO2 Structure. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 303, 120886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Hao, J.; Wu, Y.; Xing, S. Non-Radical Activation of Peroxymonosulfate with Oxygen Vacancy-Rich Amorphous MnOx for Removing Sulfamethoxazole in Water. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 436, 135260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ji, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, D.; Liu, S.; Huang, H. Highly Efficient Ozone Decomposition against Harsh Environments over Long-Term Stable Amorphous MnOx Catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 315, 121552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, J.; Xu, P.; Zhao, K.; Tong, Q.; Lu, W.; He, D. The Structural Evolution of MnOx with Calcination Temperature and Their Catalytic Performance for Propane Total Oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 565, 150596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Lan, J.; Hu, H.; Jia, F.; Ai, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Surface Oxygen Vacancy-Dependent Molecular Oxygen Activation for Propane Combustion over α-MnO2. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Ren, Q.; Zou, S.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, J.; Fu, M.; Mo, D.; et al. Highly Efficient Mesoporous MnO2 Catalysts for the Total Toluene Oxidation: Oxygen-Vacancy Defect Engineering and Involved Intermediates Using in Situ DRIFTS. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 264, 118464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.-H.; Zhang, S.; Qin, Y.-H.; Chen, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.-W. Highly Disordered MnOx Catalyst for NO Oxidation at Medium–Low Temperatures. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Wang, R.; Shi, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L. Modulating the Steric Effect over High-Index Facet of MnOx Catalysts to Enhance Toluene Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liang, X.; Liu, H.; Cao, H.; Liu, X.; Jin, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Wu, X. Activation of Co-O Bond in (110) Facet Exposed Co3O4 by Cu Doping for the Boost of Propane Catalytic Oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Kim, M.; Cao, M.; Xie, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Nanjundan, A.K.; et al. Nitrogen and Sulfur Co-Doped Hierarchically Porous Carbon Nanotubes for Fast Potassium Ion Storage. Small 2022, 18, 2203545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, P.; Shi, L.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Gao, F.; Ha, Y.; Yin, J.; Liu, M.; Pan, H.; Wu, R. Fe-Doping-Induced Cation Substitution and Anion Vacancies Promoting Co3O4 Hexagonal Nanosheets for Efficient Overall Water Splitting. Mater. Today Catal. 2023, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Sun, S.; Xie, D.; Dai, S.; Shao, W.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, C.; Liang, G.; Li, X. Engineering Defective Co3O4 Containing Both Metal Doping and Vacancy in Octahedral Cobalt Site as High Performance Catalyst for Methane Oxidation. Mol. Catal. 2024, 553, 113768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Feng, S.; Shen, B.; Li, Z.; Gao, P.; Zhang, C.; Shi, G. Simultaneous Removal NO and Toluene over the Sb Enhanced MnOx Catalysts. Fuel 2024, 360, 130533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Leng, X.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, F.; Niu, X.; Zhu, Y. Synthesis of CeaMnOx Hollow Microsphere with Hierarchical Structure and Its Excellent Catalytic Performance for Toluene Combustion. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 245, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Deng, W.; Han, J.; Qin, L.; Zhao, B.; Guo, L.; Xing, F. Study on the Structure-Activity Relationship of Fe-Mn Oxide Catalysts for Chlorobenzene Catalytic Combustion. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395, 125172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hong, D.; Xia, H.; Sun, W.; Shao, S.; Gong, B.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Dai, Q. Amorphous and Homogeneously Zr-Doped MnOx with Enhanced Acid and Redox Properties for Catalytic Oxidation of 1,2-Dichloroethane. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Qu, Z. Effect of Alkaline Earth Metal Promoter on Catalytic Activity of MnO2 for the Complete Oxidation of Toluene. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 104, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Xu, T.; Zhang, P. Atomically Dispersed Y or La on Birnessite-Type MnO2 for the Catalytic Decomposition of Low-Concentration Toluene at Room Temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 17532–17542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Cui, Z.; Guo, P.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Li, Z. Fabrication of Ru/WO3-W2N/N-Doped Carbon Sheets for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 636, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S.; Lin, M.; Qi, P.; Shi, J.; Song, G.; Fan, W.; Sui, K.; Gao, C. Interfacial and Build-in Electric Fields Rooting in Gradient Polyelectrolyte Hydrogel Boosted Heavy Metal Removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 444, 136541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wu, B.; Yu, L.; Crocker, M.; Shi, C. Investigation into the Catalytic Roles of Various Oxygen Species over Different Crystal Phases of MnO2 for C6H6 and HCHO Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 6176–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Cen, W. Mechanism of Ce-Modified Birnessite-MnO2 in Promoting SO2 Poisoning Resistance for Low-Temperature NH3-SCR. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4125–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, C.; Muhammad, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Z. Solvent-Induced Fabrication of Cu/MnOx Nanosheets with Abundant Oxygen Vacancies for Efficient and Long-Lasting Photothermal Catalytic Degradation of Humid Toluene Vapor. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 328, 122509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Rong, S.; Jia, J. Creating Water-Resistant Oxygen Vacancies in δ-MnO2 by Chlorine Introduction for Catalytic Ozone Decomposition at Ambient Temperature. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 335, 122900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Guo, X.; Mao, D.; Meng, T.; Yu, J.; Ma, Z. Unveiling the Temperature-Dependent Effect of Zn on Phosphotungstic Acid-Modified MnOx Catalyst for Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx: A Poison at <180 °C or a Promoter at >180 °C. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Fu, K.; Zheng, Y.; Han, R.; Liu, C.; Ji, N.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q. Acid Etching-Induced In Situ Growth of λ-MnO2 over CoMn Spinel for Low-Temperature Volatile Organic Compound Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10381–10390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, S.; Zhang, P.; Liu, F.; Yang, Y. Engineering Crystal Facet of α-MnO2 Nanowire for Highly Efficient Catalytic Oxidation of Carcinogenic Airborne Formaldehyde. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 3435–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Wang, B.; Bing, Q.; Zalibera, M.; Büchel, R.; Xu, R.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Gianolio, D.; Tang, C.C.; et al. Adsorption and Activation of Molecular Oxygen over Atomic Copper(I/II) Site on Ceria. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Kong, F.; Wu, C.; Duan, H.; Yang, D. Pt-Stabilized Electron-Rich Ir Structures for Low Temperature Methane Combustion with Enhanced Sulfur-Resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Jiang, F.; Xiong, G.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Fei, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; et al. Revelation of Mn4+-Osur-Mn3+ Active Site and Combined Langmuir-Hinshelwood Mechanism in Propane Total Oxidation at Low Temperature over MnO2. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Yuan, Z.-Y. CrOx Supported on High-Silica HZSM-5 for Propane Dehydrogenation. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 47, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).