Life Cycle Analysis of a Green Solvothermal Synthesis of LFP Nanoplates for Enhanced LIBs in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

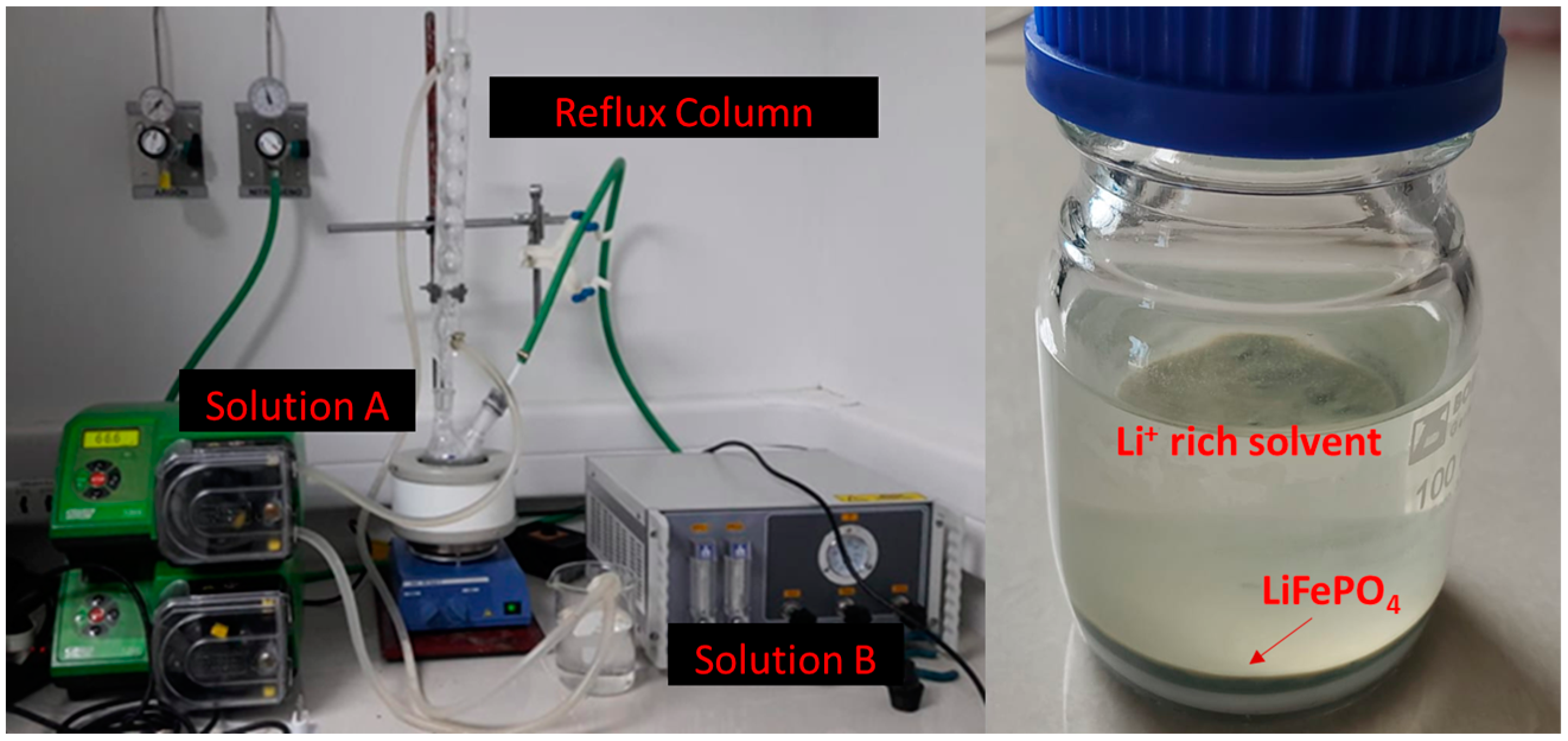

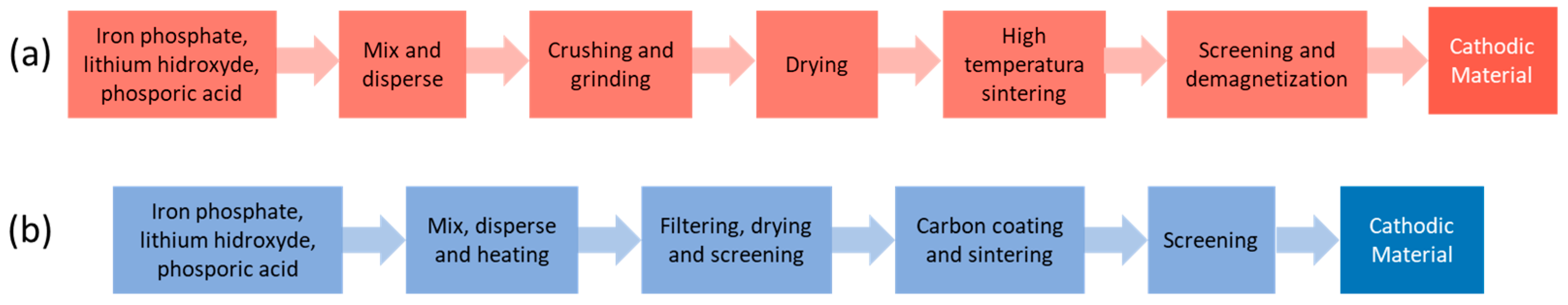

2.1. LiFePO4/C Synthesis

2.2. Electrochemical Characterization

2.3. LCA

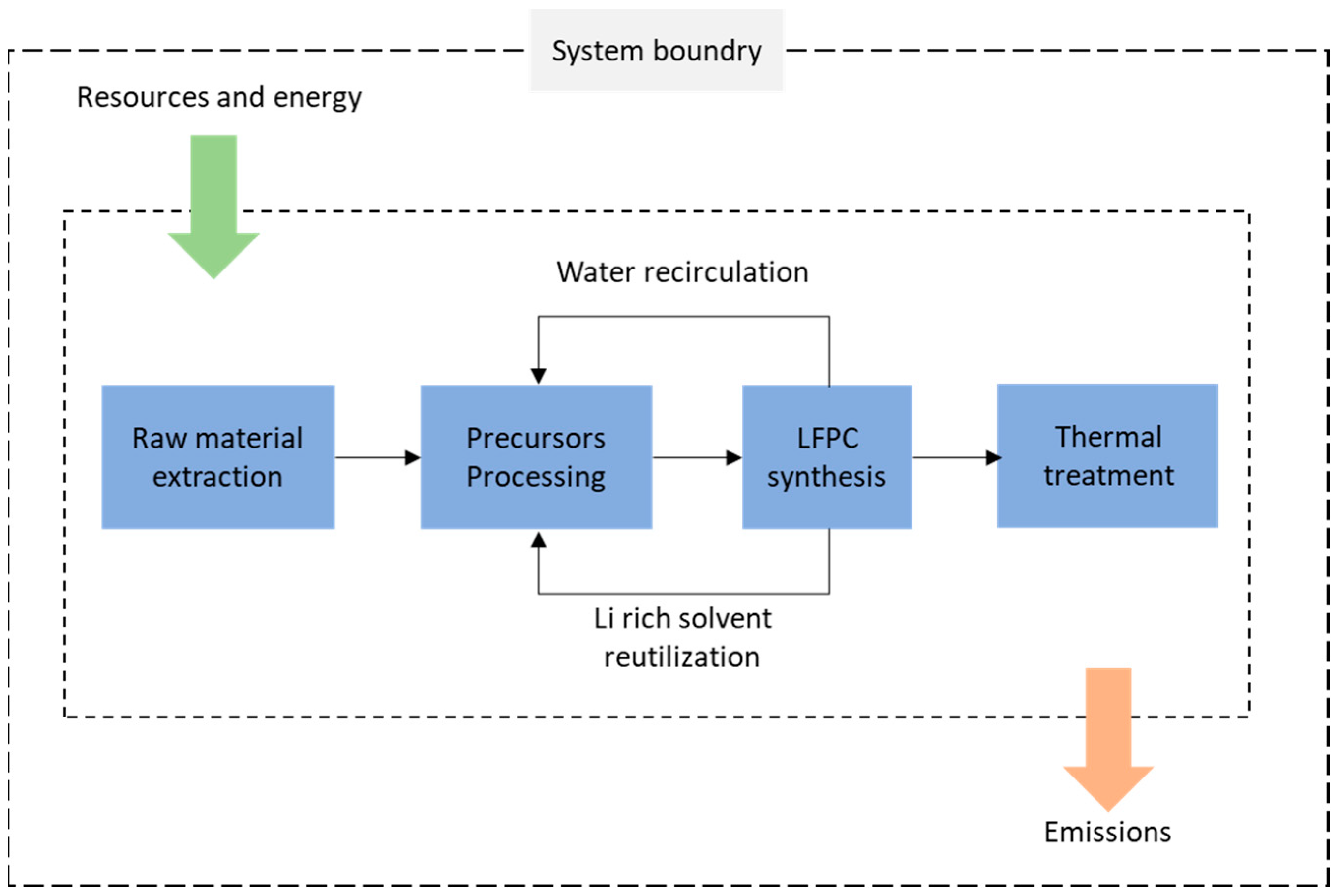

2.3.1. Scope and Function Unit

2.3.2. Life Cycle Impact Assessment Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

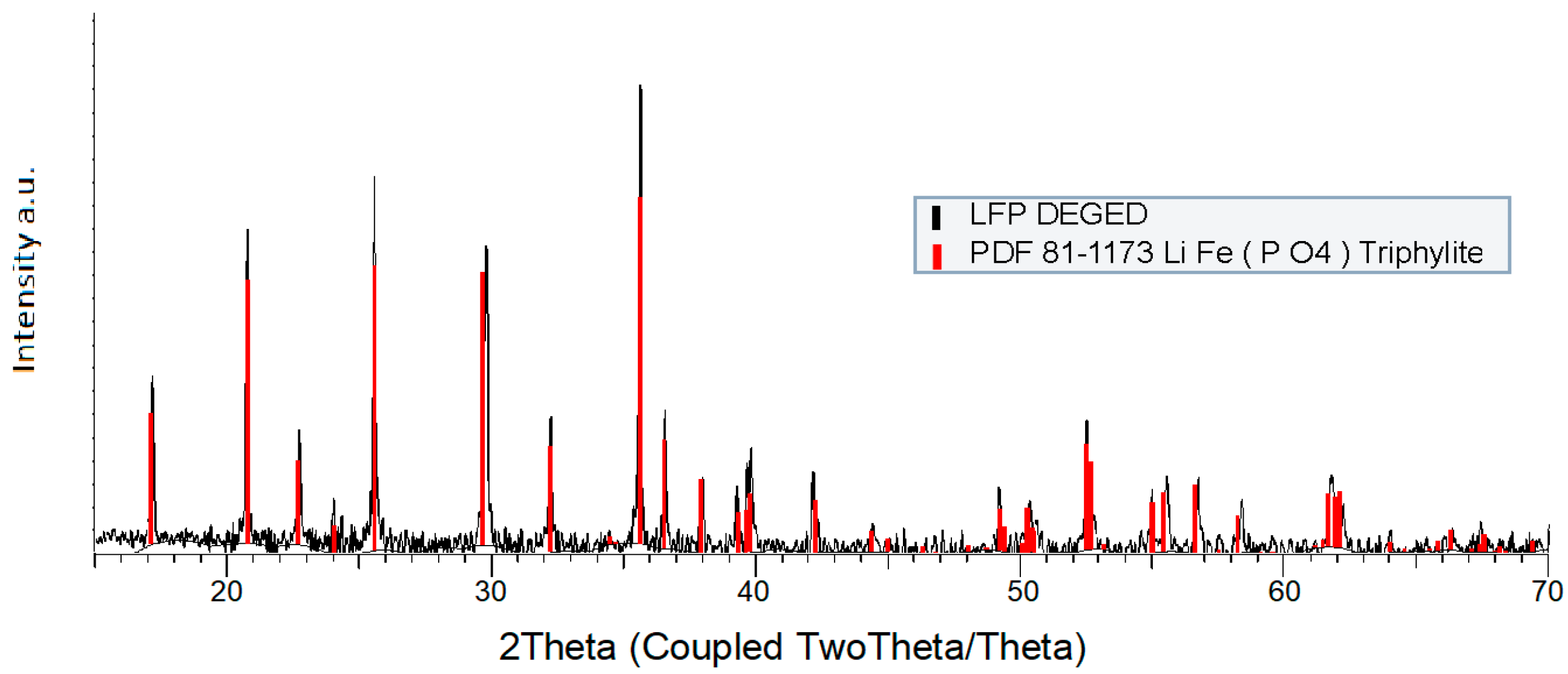

3.1. Chemical and Morphological Characterization

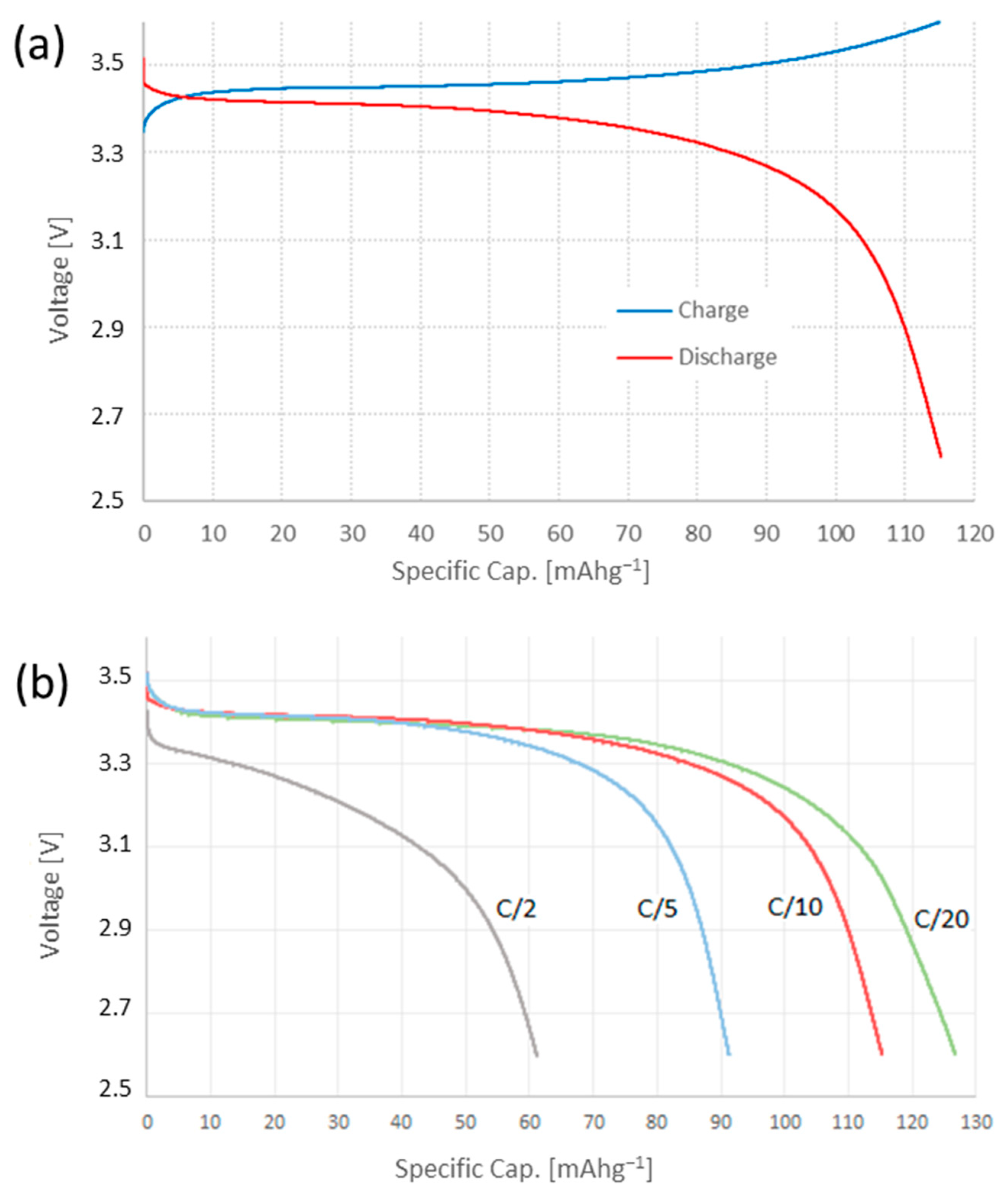

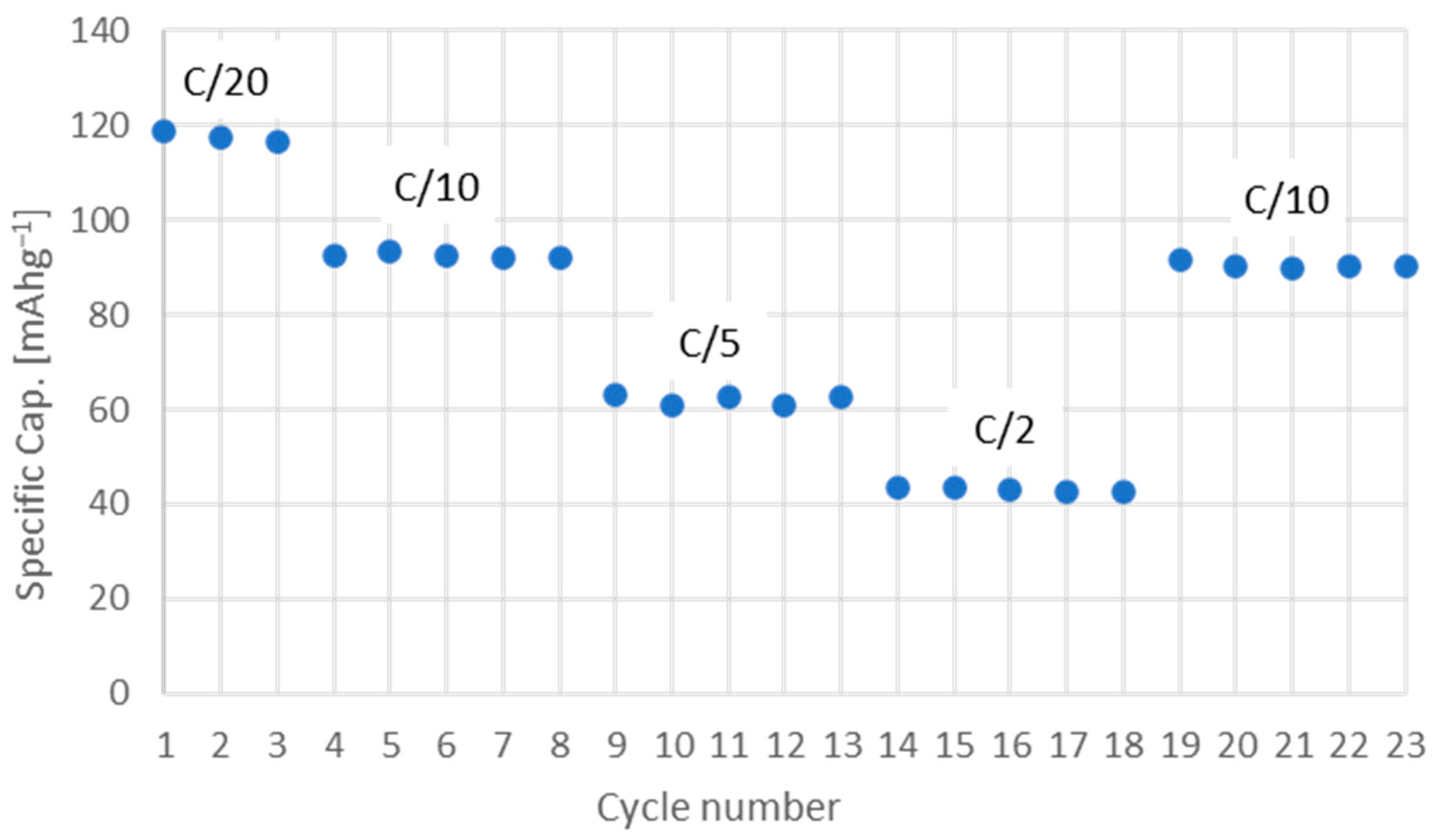

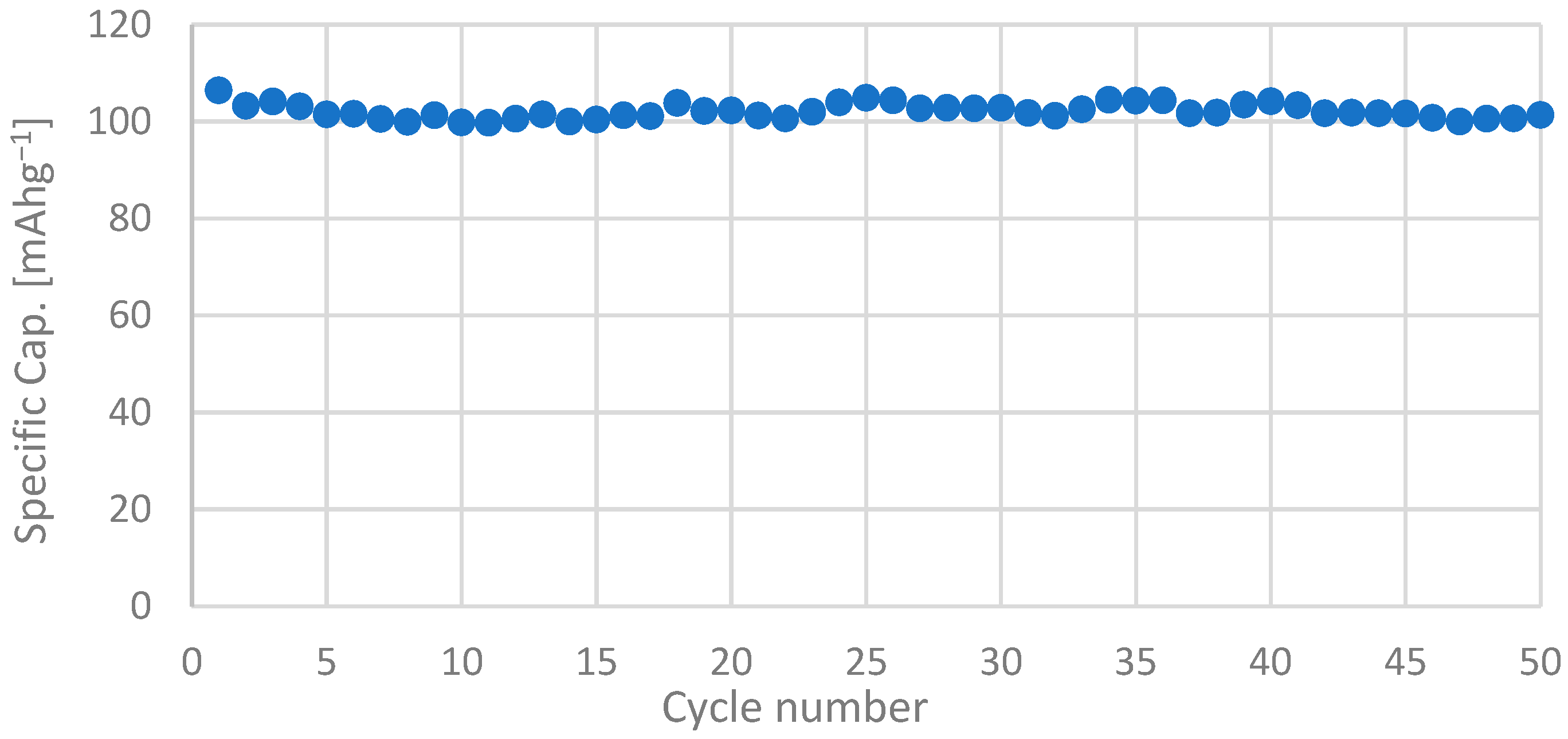

3.2. Electrochemical Characterization

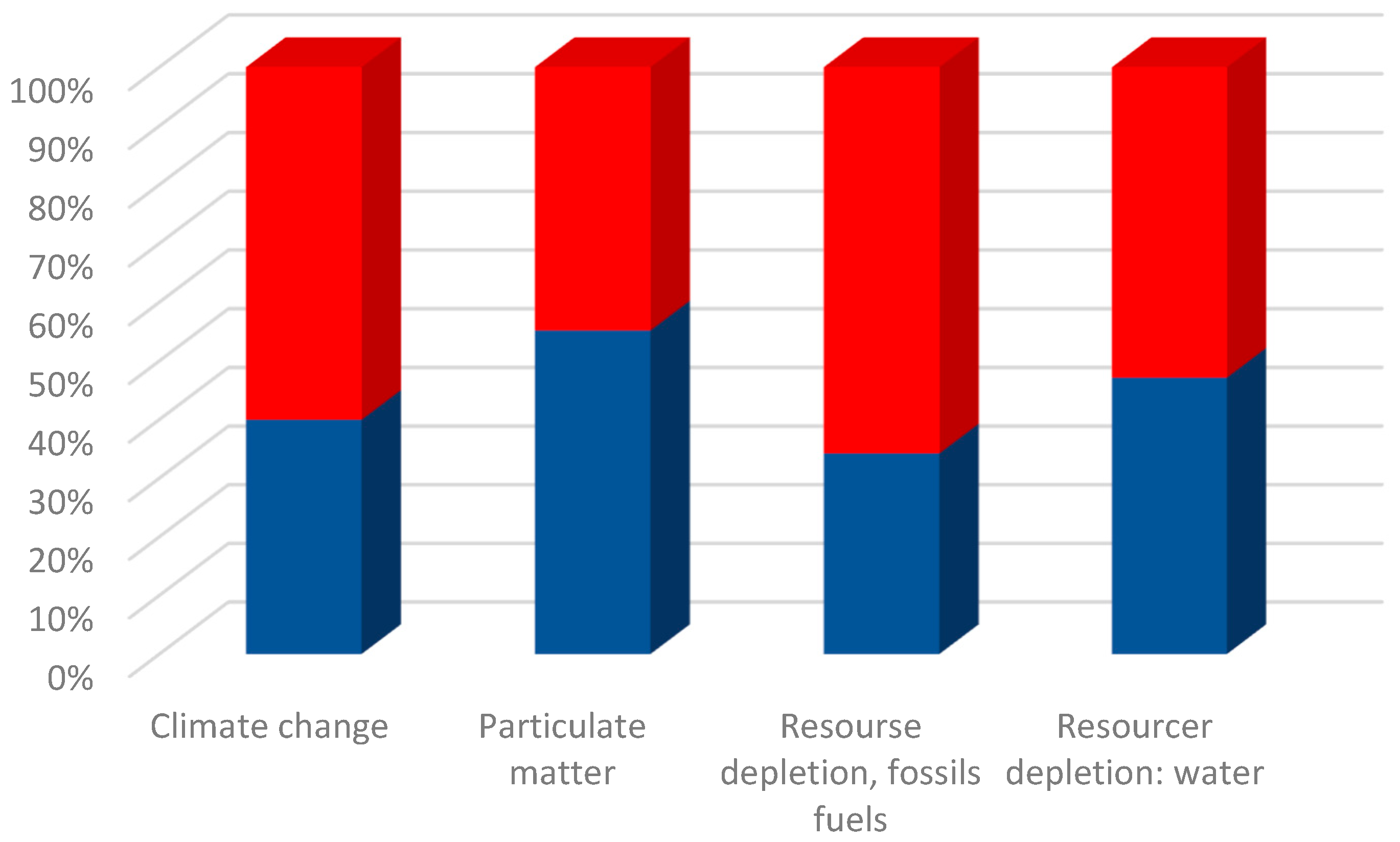

3.3. Life Cycle Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koroma, M.S.; Costa, D.; Philippot, M.; Cardellini, G.; Hosen, M.S.; Coosemans, T.; Messagie, M. Life cycle assessment of battery electric vehicles: Implications of future electricity mix and different battery end-of-life management. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Pang, B. China’s Development on New Energy Vehicle Battery Industry: Based on Market and Bibliometrics. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 581, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woody, M.; Vaishnav, P.; Keoleian, G.A.; De Kleine, R.; Kim, H.C.; Anderson, J.E.; Wallington, T. The role of pickup truck electrification in the decarbonization of light-duty vehicles. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 034031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llusco, A.; Grageda, M.; Ushak, S. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies on synthesis of Mg-doped LiMn2O4 nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2020, 10, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayfutdinov, T.; Vorobev, P. Optimal utilization strategy of the LiFePO4 battery storage. Appl. Energy 2022, 316, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, J.; Aparicio, M. Sol-Gel synthesis of nanocrystalline mesoporous Li4Ti5O12 thin-films as anodes for li-ion microbatteries. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeeban, R.; Saminathan, K.; Manojkumar, K.; Dilsha, C.; Krishnaraj, S. Battery economy: Past, present and future. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Lu, Y. Toward uniform in situ carbon coating on nano-LiFePO4 via a solid-state reaction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 13549–13555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, A.K.; Nanjundaswamy, K.S.; Goodenough, J.B. Phospho-olivines as positive-electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Junming, L.; Xiaochen, Y.; Hainan, S.; Xin, Y.; Jing, P.; Hongxu, X. Safety Analysis and System Design of Lithium Iron Phosphate Battery in Substation. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 256, 01017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, X.; Negnevitsky, M. Connecting battery technologies for electric vehicles from battery materials to management. iScience 2022, 25, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gao, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. Review—Recent Developments in the Doped LiFePO4 Cathode Materials for Power Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, A2600–A2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofre, P.; Quispe, A.; Grageda, M. Effect of particle-size distribution on LiFePO4 cathode electrochemical performance in Li-ion cells. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quím. 2022, 21, Mat2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, X. Factors that affect activation energy for Li diffusion in LiFePO4: A first-principles investigation. Solid State Ion. 2010, 181, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Bae, C.; Denlinger, A.; Miller, T. Electric vehicles batteries: Requirements and challenges. Joule 2020, 4, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Huang, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Yang, M. Asymmetric phenomenon of flow and heat transfer in charging process of thermal energy storage based on an entire domain model. Appl. Energy 2022, 316, 119122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Grágeda, M.; Quispe, A.; Ushak, S.; Sistat, P.; Cretin, M. Application and analysis of bipolar membrane electrodialysis for LiOH production at high electrolyte concentrations: Current scope and challenges. Membranes 2021, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.S.; Lee, S.J.; Yu, Y.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.M.; Theerthagiri, J.; Choi, M.Y. Novel approach for the synthesis and recovery of lithium carbonate using a pulsed laser irradiation technique. Mater. Lett. 2022, 308, 131218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosu, A.Y.; Kanari, N.; Bartier, D.; Vaughan, J.; Chagnes, A. Novel extraction route of lithium from α-spodumene by dry chlorination. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 21468–21481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiefeng, X.; Jia, L.; Zhenming, X. Novel Approach for in Situ Recovery of Lithium Carbonate from Spent Lithium Ion Batteries Using Vacuum Metallurgy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 11960–11966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Ding, Q.; An, X.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, M.; Fu, D. Preparation of LiFePO4/C cathode materials via a green synthesis route for lithium-ion battery applications. Materials 2018, 11, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Guang, T.; Hu, M.; Cheng, R.; Wang, R.; Shi, C.; Chen, J.; Hou, P.; Zhu, K. Green synthesis of high-performance LiFePO4 nanocrystals in pure water. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 5215–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunda, R.B. Potential environmental impacts of lithium mining. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 2020, 38, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.C.; Dai, Q.; Wang, M. Globally regional life cycle analysis of automotive lithium-ion nickel manganese cobalt batteries. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2020, 25, 371–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Gutiérrez, S.; Bouchard, J.; Laflamme, M.; Fytas, K. Project economics of lithium mines in Quebec: A critical review. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Gao, F.; Gong, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, B. Life cycle assessment of LFP cathode material production for power lithium-ion batteries. In Advances in Energy and Environmental Materials: Proceedings of Chinese Materials Conference 2017, 6–12 July 2017, Yinchuan, China; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2018; pp. 513–522. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/2279. Use of the Environmental Footprint methods to measure and communicate the life cycle environmental performance of products and organisations. Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, 471, 1–396. [Google Scholar]

- Schomberg, A.C.; Bringezu, S.; Flörke, M. Extended life cycle assessment reveals the spatially-explicit water scarcity footprint of a lithium-ion battery storage. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, J.; Marino, C.; Haering, D.; Stinner, C.; Nordlund, D.; Doeff, M.M.; Gasteiger, H.A.; Nilges, T. Facile, ethylene glycol-promoted microwave-assisted solvothermal synthesis of high-performance LiCoPO4 as a high-voltage cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 82984–82994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Mu, D.; Wu, B.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, R. Controllable synthesis of spherical precursor Ni0.8Co0.1Mn0.1(OH)2 for nickel-rich cathode material in Li-ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 9436–9445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatara, R.; Karayaylali, P.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Giordano, L.; Maglia, F.; Jung, R.; Schmidt, J.P.; Lund, I.; Shao-Horn, Y. The effect of electrode-electrolyte interface on the electrochemical impedance spectra for positive electrode in Li-ion battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A5090–A5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Diffusion impedance of electroactive materials, electrolytic solutions and porous electrodes: Warburg impedance and beyond. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 281, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zha, W.; Chen, D. Crystal growth kinetics, microstructure and electrochemical properties of LiFePO4/carbon nanocomposites fabricated using a chelating structure phosphorus source. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 3151–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Liang, G. Effect of spherical particle size on the electrochemical properties of lithium iron phosphate. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2019, 34, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguillarena, A.; Margallo, M.; Irabien, Á.; Urtiaga, A. Life cycle assessment of zinc and iron recovery from spent pickling acids by membrane-based solvent extraction and electrowinning. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 318, 115567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Balances. 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/world-energy-balances (accessed on 9 April 2023).

| Element | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Re | 10.31 | Ω |

| Rse | 110 | Ω |

| Rct | 37.48 | Ω |

| RW | 5.6 × 10−2 | ohm−1 |

| Ionic Diffusion (σ) | 6.96 × 10−12 | cm2s−1 |

| Impact Category | Top 3 Contributions to Impact Category for LFP Solvothermal Production | Top 3 Contributions to Impact Category for LFP Conventional Production |

|---|---|---|

| Climate change | Ethylene glycol production (0.575 kg CO2 eq) | Electricity generation from hard coal (0.891 kg CO2 eq) |

| Electricity generation from hard coal (0.369 kg CO2 eq) | Phosphate rock obtained at mine (0.471 kg CO2 eq) | |

| Iron (II) sulphate production (0.323 kg CO2 eq) | Liquid ammonia production (0.466 kg CO2 eq) | |

| Particulate matter | Ethylene glycol production (1.036 × 10−7 kg PM 2.5 eq) | Electricity generation from hard coal (4.8 × 10−7 kg PM 2.5 eq) |

| Iron (II) sulfate production (6.9 × 10−8 kg 2.5 eq) | Ferrite (iron ore) obtained at mine (6.34 × 10−8 kg PM 2.5 eq) | |

| Electricity generation from diesel (5.6 × 10−8 kg PM 2.5 eq) | Phosphate rock obtained at mine (3.6 × 10−8 kg PM 2.5 eq) | |

| Resource depletion: fossil fuels | Ethylene glycol production (15.057 kg Sb eq) | Electricity generation from diesel (14.018 Kg Sb eq) |

| Iron (II) sulfate production (6.95 kg Sb eq) | Sulphur production (9.760 kg Sb eq) | |

| Electricity generation from hard coal (3.72 kg Sb eq) | Electricity generation from hard coal (8.627 kg Sb eq) | |

| Resource depletion: water | Iron (II) sulfate production (0.452 m3 depriv) | Liquid ammonia production (0.542 m3 depriv) |

| Ethylene glycol production (0.231 m3 depriv) | Electricity generation from hydropower (0.197 m3 depriv) | |

| Phosphoric acid production (0.113 m3 depriv) | Soda ash production (0.164 m3 depriv) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cofré, P.; Viton, M.d.L.; Ushak, S.; Grágeda, M. Life Cycle Analysis of a Green Solvothermal Synthesis of LFP Nanoplates for Enhanced LIBs in Chile. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13091486

Cofré P, Viton MdL, Ushak S, Grágeda M. Life Cycle Analysis of a Green Solvothermal Synthesis of LFP Nanoplates for Enhanced LIBs in Chile. Nanomaterials. 2023; 13(9):1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13091486

Chicago/Turabian StyleCofré, Patricio, María de Lucia Viton, Svetlana Ushak, and Mario Grágeda. 2023. "Life Cycle Analysis of a Green Solvothermal Synthesis of LFP Nanoplates for Enhanced LIBs in Chile" Nanomaterials 13, no. 9: 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13091486

APA StyleCofré, P., Viton, M. d. L., Ushak, S., & Grágeda, M. (2023). Life Cycle Analysis of a Green Solvothermal Synthesis of LFP Nanoplates for Enhanced LIBs in Chile. Nanomaterials, 13(9), 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13091486