In Vitro Evaluation of the Effect of Microabrasion and Resin Infiltration Materials on Enamel Microhardness and Penetration Depth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Enamel Samples

2.2. Sample Allocation

2.3. Initial Surface Microhardness Measurement

2.4. pH Cycling Protocol

2.5. Surface Microhardness Measurement After Demineralization

2.6. Application of Microabrasion Technique (Groups G1 and G3)

2.7. Application of the ICON Resin Infiltrant (Groups G3 and G4)

2.8. Application of the Experimental Resin Infiltrant (Groups G1 and G2)

2.9. Examination of Resin Penetration Depth

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

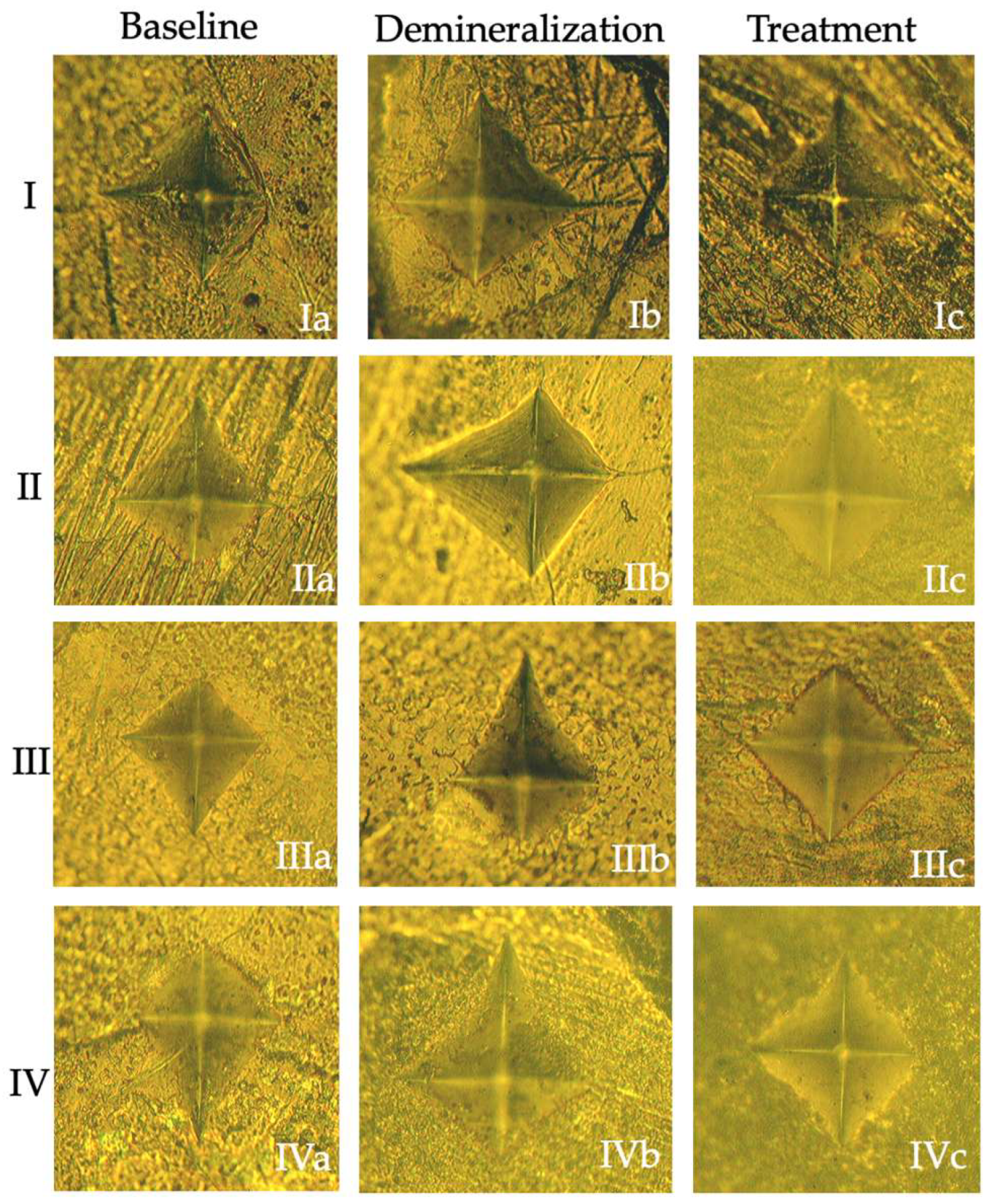

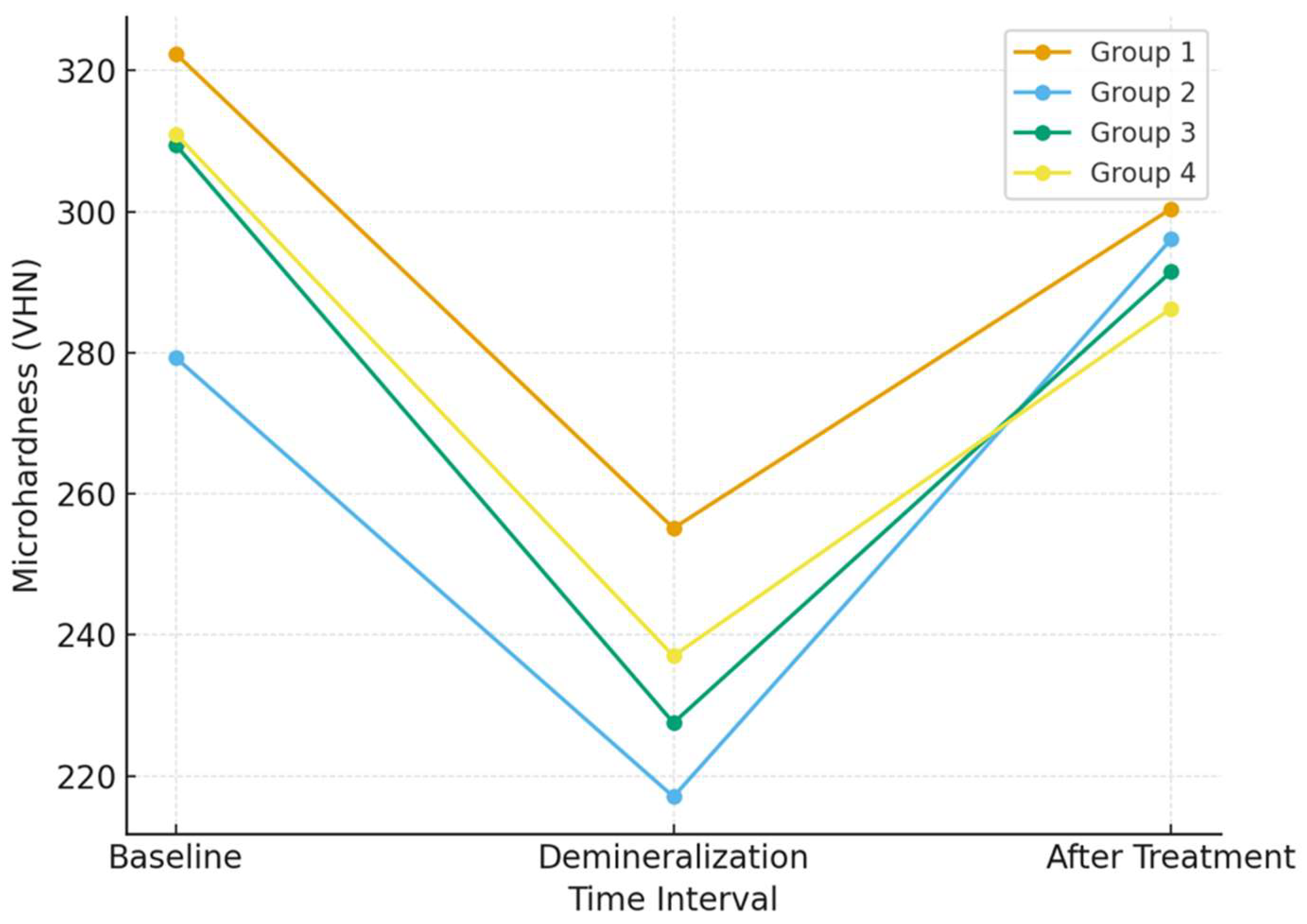

3.1. Microhardness Analysis

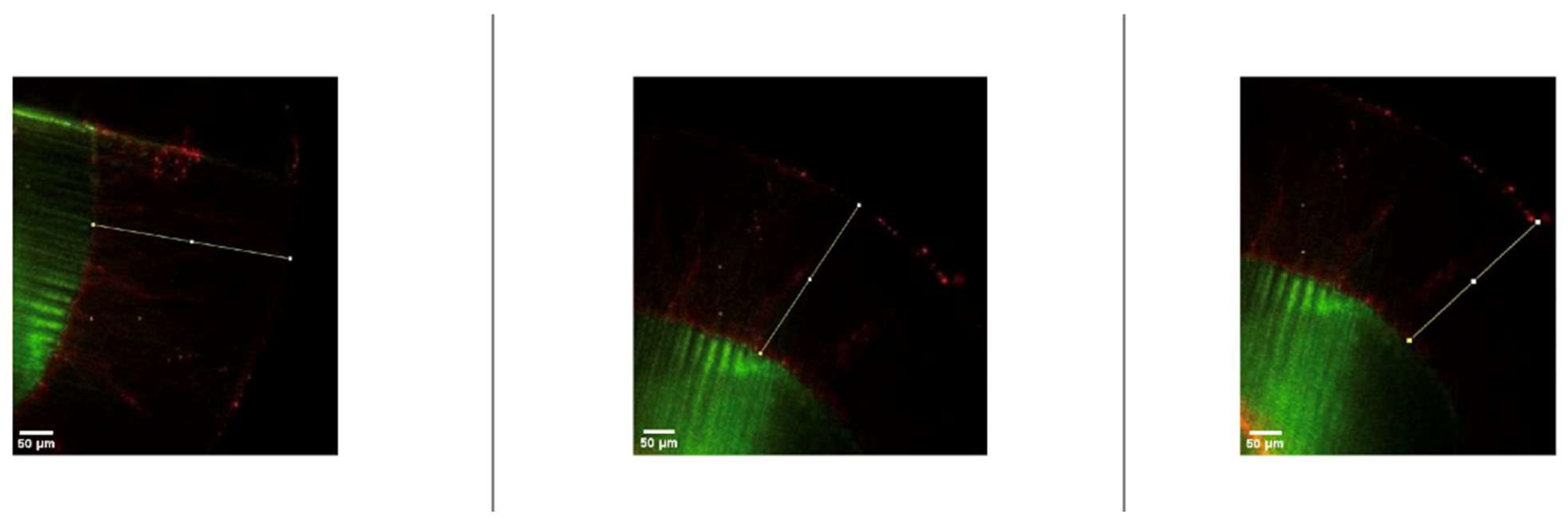

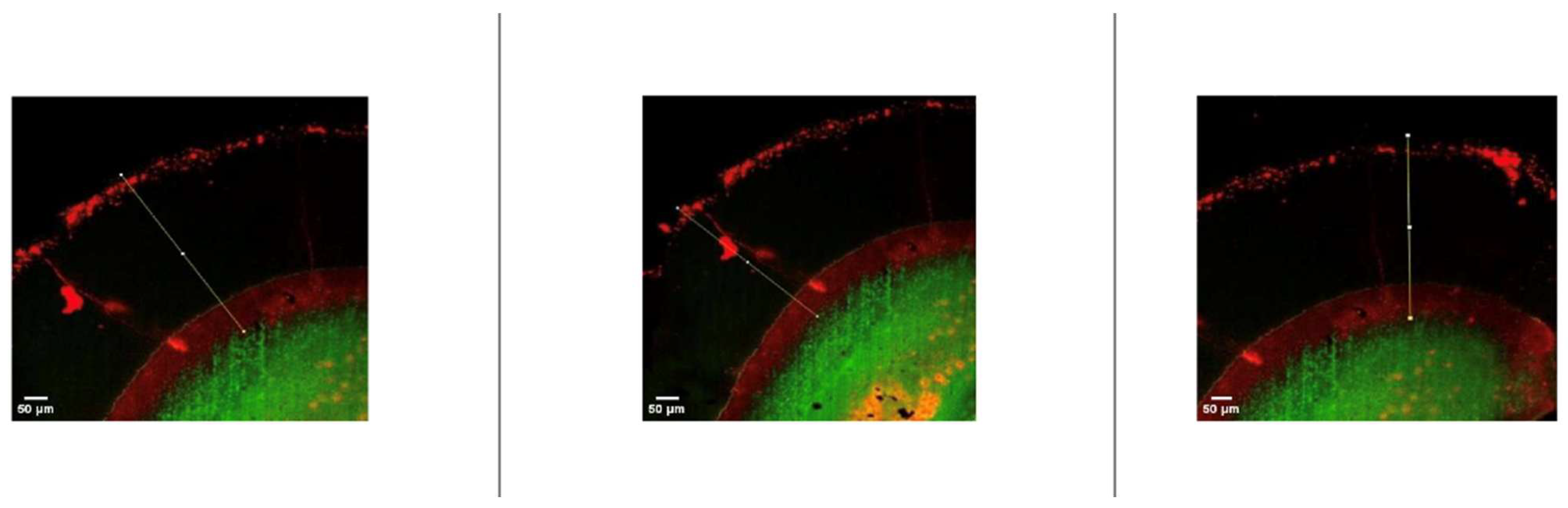

3.2. Penetration Depth Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Resin infiltration resulted in partial recovery of enamel surface microhardness after artificial demineralization; however, baseline hardness values were not fully restored, indicating surface stabilization rather than true remineralization.

- No significant differences in surface microhardness recovery were observed between the experimental resin infiltrant and the ICON system.

- The experimental resin infiltrant demonstrated measurable penetration into demineralized enamel lesions but exhibited significantly lower penetration depth compared with the commercially available ICON system.

- Microabrasion significantly increased resin penetration depth for both infiltrant materials; however, this effect did not translate into improved surface microhardness and should be interpreted cautiously due to the risk of irreversible enamel loss.

- These findings support the study objectives and hypotheses by confirming that the experimental resin can infiltrate demineralized enamel and contribute to lesion stabilization, while highlighting that its infiltration efficiency remains inferior to that of the ICON system.

- Overall, resin infiltration should be regarded as a lesion-arrest strategy, and further optimization of experimental resin formulations is required to achieve penetration performance comparable to established commercial systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pitts, N.B.; Zero, D.T.; Marsh, P.D.; Ekstrand, K.; Weintraub, J.A.; Ramos-Gomez, F.; Tagami, J.; Twetman, S.; Tsakos, G.; Ismail, A. Dental caries. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcenes, W.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Bernabé, E.; Flaxman, A.; Naghavi, M.; Lopez, A.; Murray, C.J.L. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990–2010: A systematic analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gölz, L.; Simonis, R.A.; Reichelt, J.; Stark, H.; Frentzen, M.; Allam, J.P.; Probstmeier, R.; Winter, J.; Kraus, D. In Vitro biocompatibility of ICON® and TEGDMA on human dental pulp stem cells. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.A.; Roberts, W.E.; Eckert, G.J.; Kula, K.S.; González-Cabezas, C. Risk factors for incidence and severity of white spot lesions during treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 138, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.; Tikku, T.; Khanna, R.; Sachan, K. Risk factors and management of white spot lesions in orthodontics. J. Orthod. Sci. 2013, 2, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, A.M.; Potra Cicalău, G.I.; Ciavoi, G. A Review of White Spot Lesions: Development and Treatment with Resin Infiltration. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekizer, A.; Zorba, Y.O.; Uysal, T.; Ayrikcil, S. Effects of demineralizaton-inhibition procedures on the bond strength of brackets bonded to demineralized enamel surface. Korean J. Orthod. 2012, 42, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, B.; Shivanna, V. Novel treatment of white spot lesions: A report of two cases. J. Conserv. Dent. 2011, 14, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, V.; Arun Kumar, S.; Arumugam, S.B.; Anand, V.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Methippara, J.J. Is Resin Infiltration a Microinvasive Approach to White Lesions of Calcified Tooth Structures? A Systemic Review. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2019, 12, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, E.Y.; Jeong, T.S.; Kim, J.W. The evaluation of resin infiltration for masking labial enamel white spot lesions. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2011, 21, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S.; Hopfenmuller, W.; Meyer-Lueckel, H. Resin infiltration of caries lesions: An efficacy randomized trial. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.; Rosa, P.; Ferreira, N.S.; Borges, A.B.; Torres, C.R.G.; Bü Hler Borges, A. Effect of Caries Infiltration Technique and Fluoride Therapy on Microhardness of Enamel Carious Lesions. Oper. Dent. 2012, 37, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorri, M.; Dunne, S.M.; Walsh, T.; Schwendicke, F. Micro-invasive interventions for managing proximal dental decay in primary and permanent teeth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD010431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, S.; Meyer-Lueckel, H. Infiltrants inhibit progression of natural caries lesions in vitro. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavuz, B.S.; Kargul, B. Comparative evaluation of the spectral-domain optical coherence tomography and microhardness for remineralization of enamel caries lesions. Dent. Mater. J. 2021, 40, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafifi, A.; Yassen, A.A.; Hassanein, O.E. Effectiveness of polyacrylic acid-bioactive glass air abrasion preconditioning with NovaMin remineralization on the microhardness of incipient enamel-like lesion. J. Conserv. Dent. 2019, 22, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Lueckel, H.; Paris, S. Improved resin infiltration of natural caries lesions. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.E.A.; Ismail, H.S.; Hamama, H. Evaluation methods of artificial demineralization protocols for coronal dentin: A systematic review of laboratory studies. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, S.; Tulga Öz, F. Süt Dişi Başlangıç Mine Lezyonlarının Remineralizasyonunda Kullanılan Farklı Yapıdaki Diş Macunlarının Mikrosertlik Üzerine Etkisinin İn Vitro Koşullarda Değerlendirilmesi. Selcuk. Dent. J. 2022, 9, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amend, S.; Stork, S.; Lücker, S.; Seipp, A.; Gärtner, U.; Frankenberger, R.; Krämer, N. Influence of different pre-treatments on the resin infiltration depth into enamel of teeth affected by molar-incisor hypomineralization (MIH). Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S.; Dörfer, C.E.; Meyer-Lueckel, H. Surface conditioning of natural enamel caries lesions in deciduous teeth in preparation for resin infiltration. J. Dent. 2010, 38, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer-Lueckel, H.; Paris, S.; Kielbassa, A.M. Surface layer erosion of natural caries lesions with phosphoric and hydrochloric acid gels in preparation for resin infiltration. Caries Res. 2007, 41, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.; Subar, P.E.; Young, D.A. Dental Caries: An Update on Dental Trends and Therapy. Adv. Pediatr. 2017, 64, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, S.; Bitter, K.; Renz, H.; Hopfenmuller, W.; Meyer-Lueckel, H. Validation of two dual fluorescence techniques for confocal microscopic visualization of resin penetration into enamel caries lesions. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2009, 72, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, D.; Nayak, R.; Pai, D.; Upadhya, N.; KBhaskar, V.; Kamath, P. Effect of Resin Infiltration on Artificial Caries: An in vitro Evaluation of Resin Penetration and Microhardness. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2017, 10, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Son, H.H.; Chang, J. Color and hardness changes in artificial white spot lesions after resin infilteration, restorative dentistry and endodontics. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2012, 37, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S.; Meyer-Lueckel, H.; Colfen, H.; Kielbassa, A.M. Penetration coefficients of commercially available and experimental composites intended to infiltrate enamel carious lesions. Dent. Mater. 2007, 23, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.; Abdalhady, A.A.; Noaman, K. A Comparative study in penetration depth of resin-based materials into White spot lesion. Eur. J. Health Sci. 2020, 5, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soveral, M.; Machado, V.; Botelho, J.; Mendes, J.J.; Manso, C. Effect of resin infiltration on enamel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Funct. Biomater. 2021, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D.F.A.; Hasmun, N.N.; Liew, Y.M.; Venkiteswaran, A. Repeated Etching Cycles of Resin Infiltration up to Nine Cycles on Demineralized Enamel: Surface Roughness and Esthetic Outcomes—In Vitro Study. Children 2023, 10, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, M.P.N.C.; Pereira, T.P.; Iatarola, B.O.; Vertuan, M.; Magalhães, A.C.; Zezell, D.M.; Francisconi-Dos-Rios, L.F. Etching on the edge: Enamel loss under repeated and active HCl applications as a resin infiltration pretreatment. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2025, 33, e20250103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak-Kowalska, K.; Pels, E. In vitro and in vivo assessment of enamel colour stability in teeth treated with low-viscosity resin infiltration—A literature review. J. Stomatol. 2019, 72, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Resin Infiltrants | Composition |

|---|---|

| Experimental Resin Infiltrant | TEGDMA 80–95 wt%, camphorquinone < 2 wt% |

| ICON Resin Infiltrant | TEGDMA 70–95 wt%, camphorquinone < 2.5 wt% |

| Groups | Pretreatment Protocol | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Demineralization (Mean ± SD) | Treatment (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | With microabrasion | 322.38 ± 21.26 a | 255.12 ± 16.47 b | 300.40 ± 40.91 a |

| Group 2 | Without microabrasion | 279.28 ± 40.17 a | 217.04 ± 19.39 b | 296.08 ± 42.74 a |

| Group 3 | With microabrasion | 309.44 ± 32.26 a | 227.52 ± 48.39 b | 291.48 ± 46.32 a |

| Group 4 | Without microabrasion | 311.00 ± 39.46 a | 237.00 ± 34.45 b | 286.28 ± 29.00 a |

| Groups | Pretreatment Protocol | Resin Type | n | Penetration Depth (Mean ± SD, µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | With microabrasion | Experimental resin | 6 | 278.5 ± 18.06 a |

| Group 2 | Without microabrasion | Experimental resin | 6 | 239.30 ± 14.1 b |

| Group 3 | With microabrasion | ICON resin | 6 | 412.9 ± 18.44 c |

| Group 4 | Without microabrasion | ICON resin | 6 | 356.76 ± 6.08 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Devrimci, E.E.; Gönüllü, İ.; Kemaloğlu, H.; Türkün, M.; Demirbaş, A. In Vitro Evaluation of the Effect of Microabrasion and Resin Infiltration Materials on Enamel Microhardness and Penetration Depth. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17020067

Devrimci EE, Gönüllü İ, Kemaloğlu H, Türkün M, Demirbaş A. In Vitro Evaluation of the Effect of Microabrasion and Resin Infiltration Materials on Enamel Microhardness and Penetration Depth. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(2):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17020067

Chicago/Turabian StyleDevrimci, Elif Ercan, İdil Gönüllü, Hande Kemaloğlu, Murat Türkün, and Ayşegül Demirbaş. 2026. "In Vitro Evaluation of the Effect of Microabrasion and Resin Infiltration Materials on Enamel Microhardness and Penetration Depth" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 2: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17020067

APA StyleDevrimci, E. E., Gönüllü, İ., Kemaloğlu, H., Türkün, M., & Demirbaş, A. (2026). In Vitro Evaluation of the Effect of Microabrasion and Resin Infiltration Materials on Enamel Microhardness and Penetration Depth. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(2), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17020067