Evaluation of Self-Concept in the Project for People with Intellectual Disabilities: “We Are All Campus”

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The self-concept of an affective nature, which is understood through the perception that a person manifests regarding their emotional development (Claiborne et al. 2010);

- The self-concept of an ethical nature, which is related to the honesty and vision of that person integrated into society with the civic values marked by it (Mullins and Preyde 2013);

- The self-concept of an autonomous nature, where the individual experience is perceived as the possibility of acting according to one’s own criteria (Fonseca et al. 2019);

- The self-concept related to self-realization, which reflects the achievement of planned goals and the state of the person in respect of her objectives (Mock and Love 2012).

“We Are All Campus” Program

- Provide training aimed at improving autonomy and job preparation;

- Facilitate resources to increase labor and social inclusion of the group;

- Provide participants with comprehensive, humanistic, and multipurpose labor training, maximizing their access and maintenance possibilities in the job market;

- Establish an inclusive training and standardization system within the framework of the university community;

- Develop the motivation and interest of the participants in learning and performing the different tasks, with efficiency and responsibility.

2. Objectives and Methodological Issues

2.1. Objectives

- GO1. Analyze the influence of the “We are all Campus” program on the self-concept of people with intellectual disabilities in their inclusion expectations.

- SO1. Explore the perception of the factors that affect the self-concept of people with intellectual disabilities.

- SO2. Establish relationships with the categories that emerged between the different factors that affect the self-concept of people with disabilities.

2.2. Method

2.3. Context and Sample

2.4. Data Collection Tool, SWOT Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

- Analysis of observations that present the purpose of stimulating research. This was carried out at the beginning of it when the need was detected. Exposing the initial results of the encoding in absolute numbers.

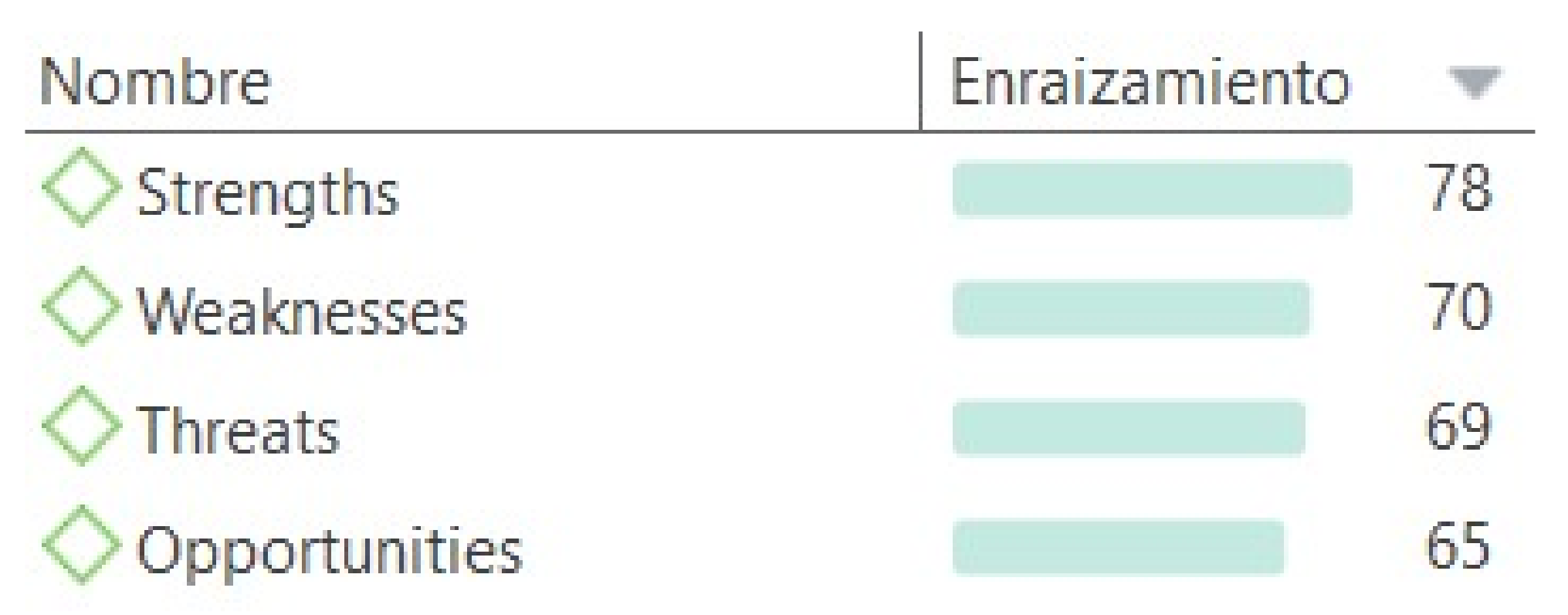

- Construction or use of descriptive systems. This consists of the coding of the extracted data to establish the categories. For this purpose, names of the SWOT matrix were deductively used as codes and, inductively, codes were created according to the topic addressed by the subjects. A more in-depth explanation of this is given in the descriptive analysis described in the next section.

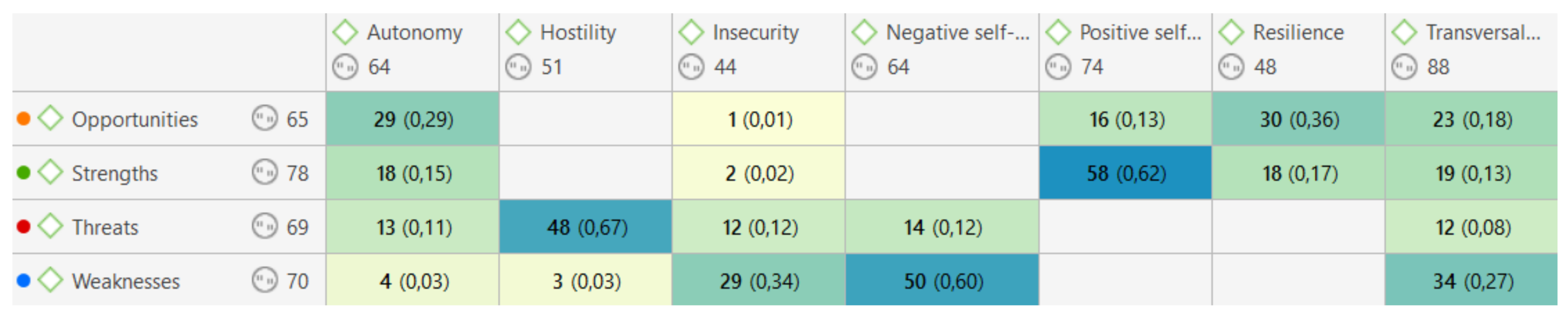

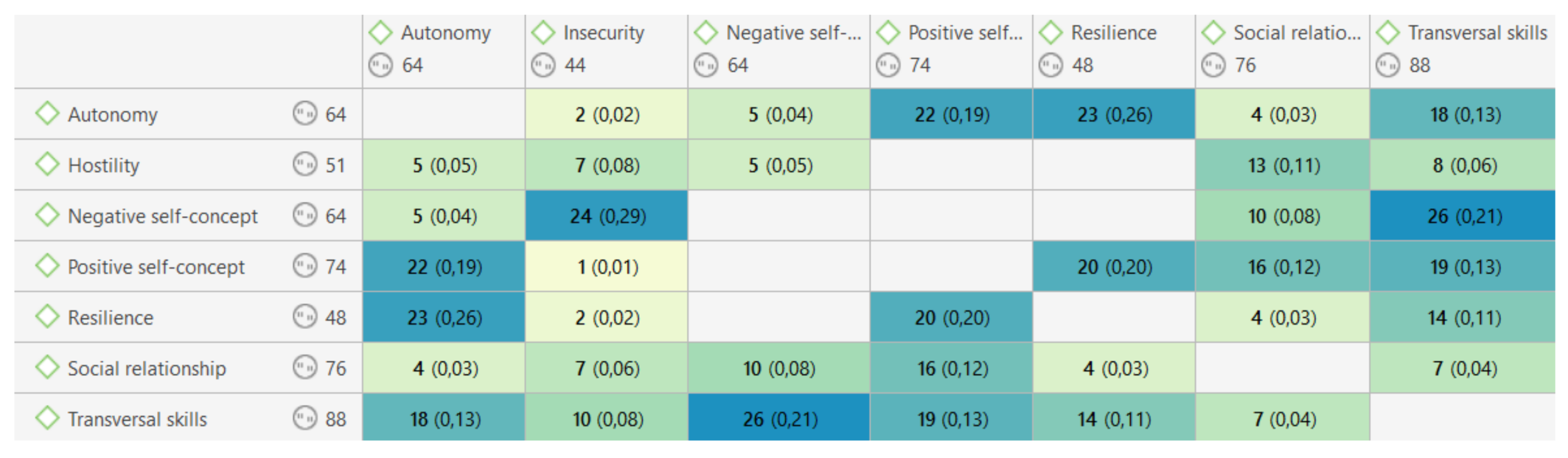

- Qualitative data suggesting relationships among variables were performed via an analysis of the co-occurrences between the emerged codes. These relationships are considered qualitative suggestions (quasi-statistics).

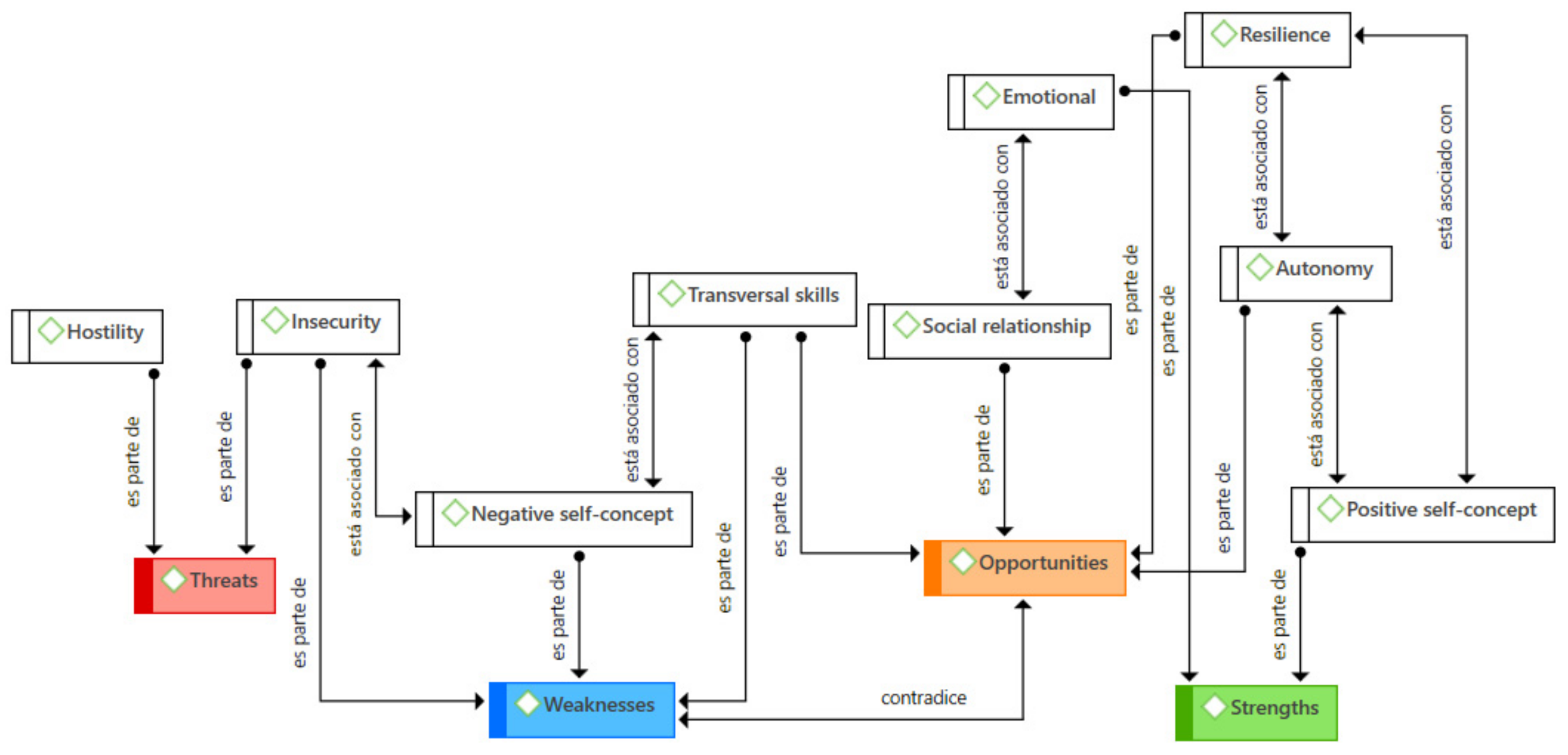

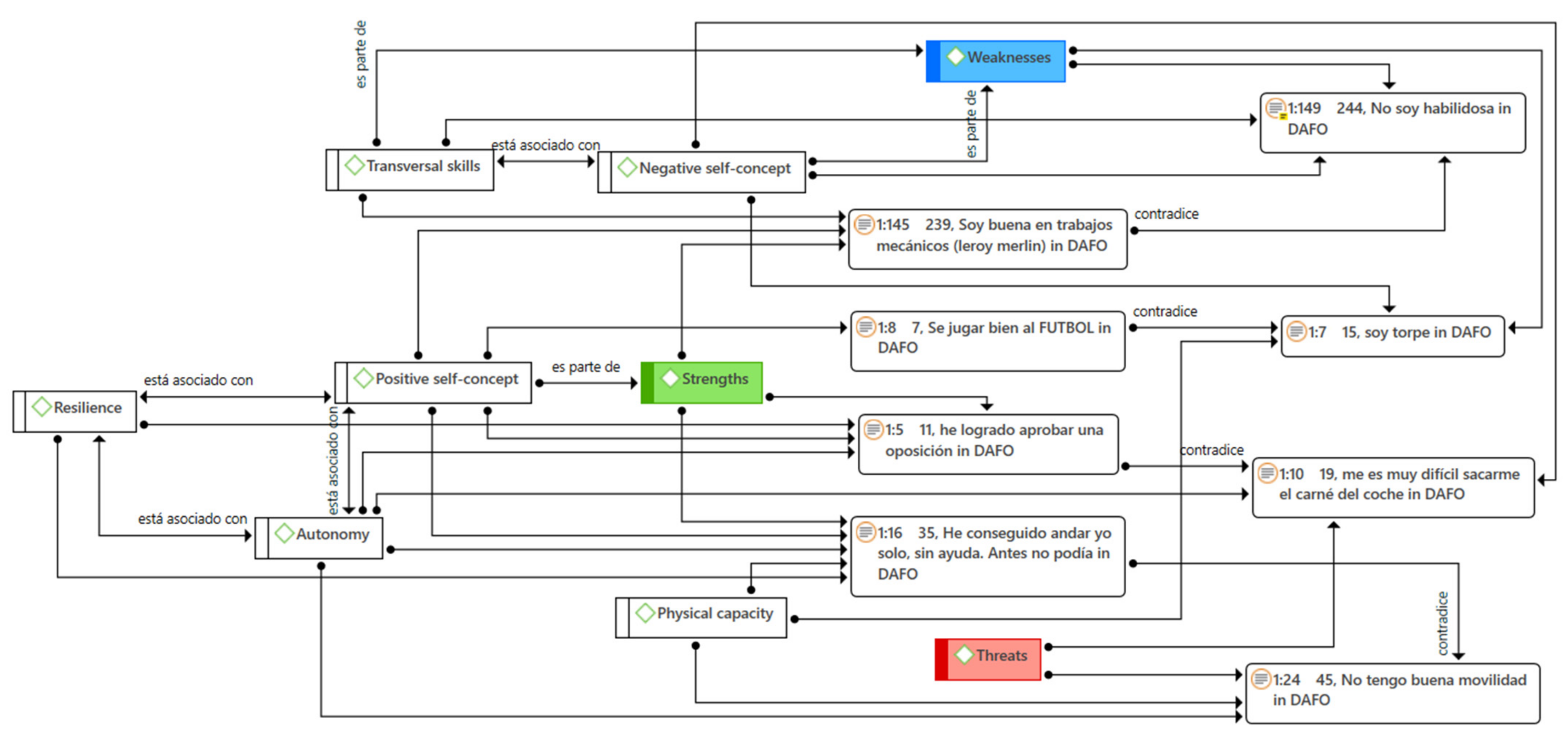

- Matrix formulations expressed through semantic networks where specific interrelations are expressed and from which different patterns can be extracted in the subjects.

- Qualitative analysis to support the theory focused on proposing trends and theoretically contrasting the different statements extracted from the analysis process.

3. Results and Discussion

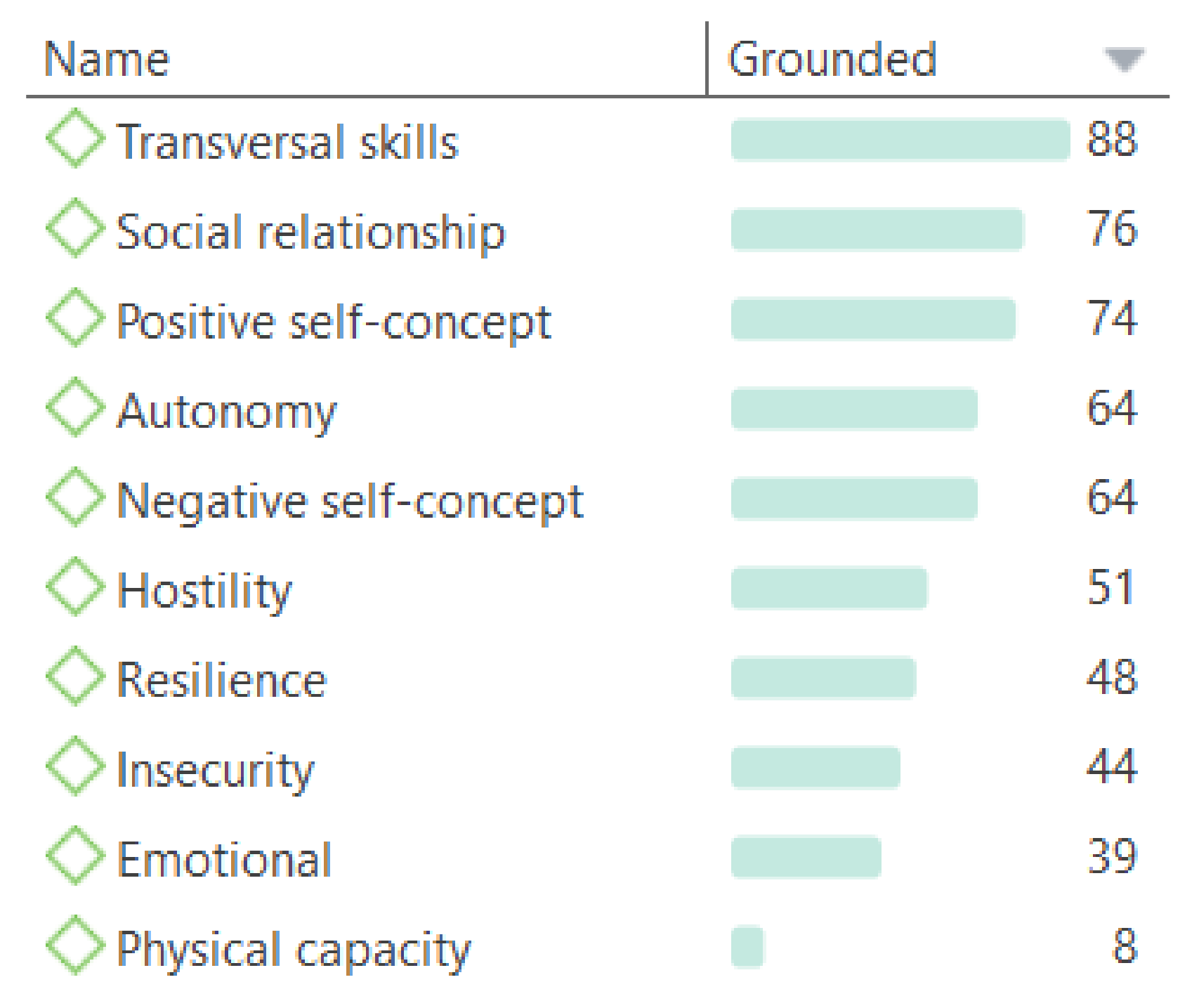

- Transversal skills: the largest of the categories in terms of quotes refers to different skills that are necessary for the daily life of the subjects, skills they express they still need, or skills they have already acquired, e.g., “I’m not good at handling money” (1:55)2.

- Social relationship: linked to quotes that refer to issues related to socialization with peers or other people, e.g., “I’m going to make friends at university” (1:28). This is highly valued by the whole sample.

- Positive/negative self-concept: the perception that subjects establish about themselves and their abilities, both negatively and positively, e.g., “I’m negative, I think everything will go wrong” (1:58).

- Autonomy: possible issues with dependency on other people or their freedom to act independently in society, e.g., “I usually do things for myself, I am independent” (1:31).

- Hostility: broad code used to indicate quotes in which harmful or aggressive aspects towards them are stated, such as bullying or lack of consideration by third parties, e.g., “Sometimes they laugh at me” (1:198).

- Resilience: adaptation with changes that provide positive results in adverse situations, in their case the cognitive deficiency itself, e.g., “I have succeeded in passing an exam” (1:5).

- Insecurity: any mention of situations of nervousness, fear, or incapacity in the face of a scenario or any problem caused by one’s perception of vulnerability, e.g., “I’m not sure if I will achieve my goals” (1:164).

- Emotional: code referring to expressions and quotes where subjects express ideas related to emotions and their stability in this sense. It was stated both positively and negatively, e.g., “Sometimes I feel excluded” (1:215).

- Physical capacity: used when referring to issues of this nature, e.g., “I have managed to walk alone, without help. I couldn’t do that before” (1:16).

4. Conclusions

- When exploring the perception of the factors that affect the self-concept of people with intellectual disabilities, it can be found that a total of eight categories have emerged. Among them, despite the substantial differences in their roots, it was observed that, to a greater or lesser extent, all of them are important for the development of the subjects and their inclusion in society. In addition, each one of them was present in a recurring way in the speech of all the subjects. Therefore, it can be concluded that, even though it is not a large sample, it has reached a theoretical saturation that allows the data to be extrapolated beyond this context.

- There was an objective to establish relationships between the categories emerged between the different factors that affect the self-concept of people with disabilities. Conceptually, a diversity of relationships developed between the codes used, both among those proposed before starting the data analysis process and among those that have emerged later. It can be inferred that there is a significant relationship between the different factors in which the subjects are involved and that an intervention from different angles, taking into account a diversity of aspects, is necessary.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | As the work was originally carried out in Spanish, the codes used are in that language. Strengths—Fortalezas; Weaknesses—Debilidades; Opportunities—Oportunidades; Threats—Amenazas. |

| 2 | To reference the citations extracted from the data, the coding offered by the ATLAS.ti 9 program has been used. Where the first number indicates the document where the appointment is located and the second is the appointment within said document. |

| 3 | In the different figures facilitated by the ATLAS.ti software, the greater intensity of the relationships is reflected in proportionally darker colours. |

References

- Arnaiz, Pilar, Remedios De Haro, and Rosa M. Maldonado. 2019. Barriers to student learning and participation in an inclusive school as perceived by future education professionals. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 8: 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz, Pilar, Remedios De Haro, Salvador Alcaraz, and Ana B. Mirete. 2020. Schools That Promote the Improvement of Academic Performance and the Success of All Students. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, Allen H., and Paul F. Lazarsfeld. 1961. Some functions of Qualitative Analysis in Social Research. In Sociology: The Progress of a Decade. Edited by Seymour Martin Lipset and Neil Joseph Smelser. Hoboken: Prentice Hall, pp. 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte, María L., Lucía Mirete, and Begoña Galián. 2020. Evaluación de la pertinencia del título universitario “We are All Campus” dirigido a personas con discapacidad intelectual. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado: RIFOP 34: 263–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsdóttir, Kristín. 2017. Belonging to higher education: Inclusive education for students with intellectual disabilities. European Journal of Special Needs Education 32: 125–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Robin, and Sara Movahedazarhouligh. 2019. Students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in inclusive higher education: Perceptions of stakeholders in a first-year experience. International Journal of Inclusive Education 25: 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunbury, Stephen. 2018. Disability in higher education–do reasonable adjustments contribute to an inclusive curriculum? International Journal of Inclusive Education 24: 964–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claiborne, Lise, Sue Cornforth, Ava Gibson, and Alezandra Smith. 2010. Supporting students with impairments in higher education: Social inclusion or cold comfort? International Journal of Inclusive Education 15: 513–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, Robert F., Elizabeth Shaunessy-Dedrick, Shannon M. Suldo, and John M. Ferron. 2015. Psychometric properties of the school attitude assessment survey-revised with international baccalaureate high school students. Gifted Child Quarterly 59: 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desombre, Caroline, Mathilde Lamotte, and Mikael Jury. 2019. French teachers’ general attitude toward inclusion: The indirect effect of teacher efficacy. Educational Psychology 39: 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Ines, Bruno Almeida, Sara Roldão, Rita Jesus, Joana Lopes, and Sofía Santos. 2019. Self-concept in persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disability in Portugal: A systematic review. Análise Psicológica 37: 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, Diane, and Barry Coughlan. 2010. Transition from special education into postschool services for young adults with intellectual disability: Irish parents’ experience. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 7: 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigal, Meg, and Debra Hart. 2010. Think College! Postsecondary Education Options for Students with Intellectual Disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Samfieri, Roberto. 2014. Metodología de la Investigación. New York: McGrawHill. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Laurence. 2011. The path of least resistance: A voice-relational analysis of disabled students’ experiences of discrimination in English universities. International Journal of Inclusive Education 15: 711–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langørgen, Eli, and Eva Magnus. 2018. We are just ordinary people working hard to reach our goals! Disabled students’ participation in Norwegian higher education. Disability & Society 33: 598–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanera, Salvador, and Gaspar Brändle. 2019. The Type of Disability as a Differential Factor in Entrepreneurship. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education 22: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Manzanera, Salvador, and Pilar Ortiz. 2017. Disability and its relationship with the labor market. Socio-labor situation. In Entrepreneurship, Employment and Disability. A Diagnosis. Edited by Pilar Ortiz and Angel Olaz. Cizur Menor: Aranzadi, pp. 45–85. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Michael B., and Allan M. Huberman. 1984. Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, London and New Delhi: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Miñano, Pablo, Raquel Gilar, and Juan L. Castejón. 2012. A structural model of cognitivemotivational variables as explanatory factors of academic achievement in Spanish language and mathematics. Anales de Psicología 28: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mock, Martha, and Kristen Love. 2012. One state’s initiative to increase access to higher education for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 9: 289–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, Anabel. 2017. Inclusive education in higher education: Challenges and opportunities. European Journal of Special Needs Education 32: 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, Anabel, and Victor H. Perera. 2018. Inclusive higher education in Spain: Students with disabilities speak out. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, Anabel, Martha Sandoval, and Fuensanta Carnerero. 2020a. Higher education inclusivity: When the disability enriches the university. Higher Education Research & Development 39: 1202–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, Anabel, Victor H. Perera, and Noelia Melero. 2020b. Difficulties and reasonable adjustments carried out by Spanish faculty members to include students with disabilities. British Journal of Special Education 47: 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, Laura, and Michele Preyde. 2013. The lived experience of students with an invisible disability at a Canadian university. Disability y Society 28: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, Anna, Joaquim Soler, Ausias Cebolla, and Ramon Cladellas. 2018. A positive psychological intervention for failing students: Does it improve academic achievement and motivation? A pilot study. Learning and Motivation 63: 126–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onion, Raquel, and Edurne Aranguren. 2021. Epistemological rethinking of the SWOT situational analysis in Social Work. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social 34: 127–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, Pilar, and Angel Olaz. 2018. Differential aspects in the entrepreneurship of people with disabilities. In Disability and Entrepreneurship. Dimensions and Interpretative Contexts in Qualitative Key. Edited by A. Olaz and P. Ortiz. Cizur Menor: Aranzadi, pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Cynthia, Maria Dahman, Emma Rose, Jinghui Cheng, and Glenn Bradford. 2016. Best practices for teaching accessibility in university classrooms: Cultivating awareness, understanding, and appreciation for diverse users. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing 8: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, Tonette. S. 2011. Challenging ableism, Understanding Disability, including Adults with Disabilities in Workplaces and Learning Spaces. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. Hoboken: John Wiley y Sons, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Álvarez, David, Estefanía Martín, and Pablo A. Haya. 2021. Collaborative Video-Based Learning Using Tablet Computers to Teach Job Skills to Students with Intellectual Disabilities. Education Sciences 11: 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Joseph B., Kristina N. Randall, Erica Walters, and Virginia Morash-MacNeil. 2019. Employment and independent living outcomes of a mixed model post-secondary education program for young adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 50: 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, Marta, Ceciclia Simón, and Gerardo Echeita. 2018. A critical review of education support practices in Spain. European Journal of Special Needs Education 34: 441–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, Kristen, Saba Kawas, Andrew J. Ko, and Richard E. Ladner. 2018. Who Teaches Accessibility? A Survey of U.S. Computing Faculty.Paper presented at the 49th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE ‘18), Baltimore, MD, USA, February 21–24; New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoecker, Randy. 1991. Evaluating and rethinking the case study. Social Review 39: 88–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bogdan, and Marjorie DeVault. 2015. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Teoli, Dac, Terrence Sanvictores, and Jason An. 2019. SWOT Analysis. NCBI Internet Bookshelf; StatPearls Publishing. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537302/ (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Van-Mieghem, Aster, Karine Verschueren, Katja Petry, and Elke Struyf. 2018. An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education 24: 675–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehmas, Simo, and Nick Watson. 2014. Moral wrongs, disadvantages, and disability: A critique of critical disability studies. Disability and Society 29: 638–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belmonte Almagro, M.L.; Bernárdez-Gómez, A. Evaluation of Self-Concept in the Project for People with Intellectual Disabilities: “We Are All Campus”. J. Intell. 2021, 9, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence9040050

Belmonte Almagro ML, Bernárdez-Gómez A. Evaluation of Self-Concept in the Project for People with Intellectual Disabilities: “We Are All Campus”. Journal of Intelligence. 2021; 9(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence9040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelmonte Almagro, María Luisa, and Abraham Bernárdez-Gómez. 2021. "Evaluation of Self-Concept in the Project for People with Intellectual Disabilities: “We Are All Campus”" Journal of Intelligence 9, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence9040050

APA StyleBelmonte Almagro, M. L., & Bernárdez-Gómez, A. (2021). Evaluation of Self-Concept in the Project for People with Intellectual Disabilities: “We Are All Campus”. Journal of Intelligence, 9(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence9040050