Mapping the Relationship Between Core Executive Functions and Mind Wandering in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mind Wandering: Definitions and Theoretical Explanations

1.2. Development of Executive Functions in Childhood and Adolescence

1.3. The Present Review

- RQ1: What is the association between EFs and MW?

- RQ2: Which EFs were most strongly associated with MW?

- RQ3: What kind of measures were utilised in the measurement of EFs and MW?

- RQ4: What are the limitations of previous approaches and what future directions for research have arisen from previous studies?

2. Materials and Methods

Keyword Search Criteria in Databases

- A combination of at least one core EF and one aspect of MW.

- Child or adolescent populations (up to 20 years old (Sawyer et al., 2018)).

- Quantitative studies.

- Peer-reviewed journal papers.

- English-language papers.

- The studies can use behavioural or self-report methodologies but not brain imaging.

3. Results

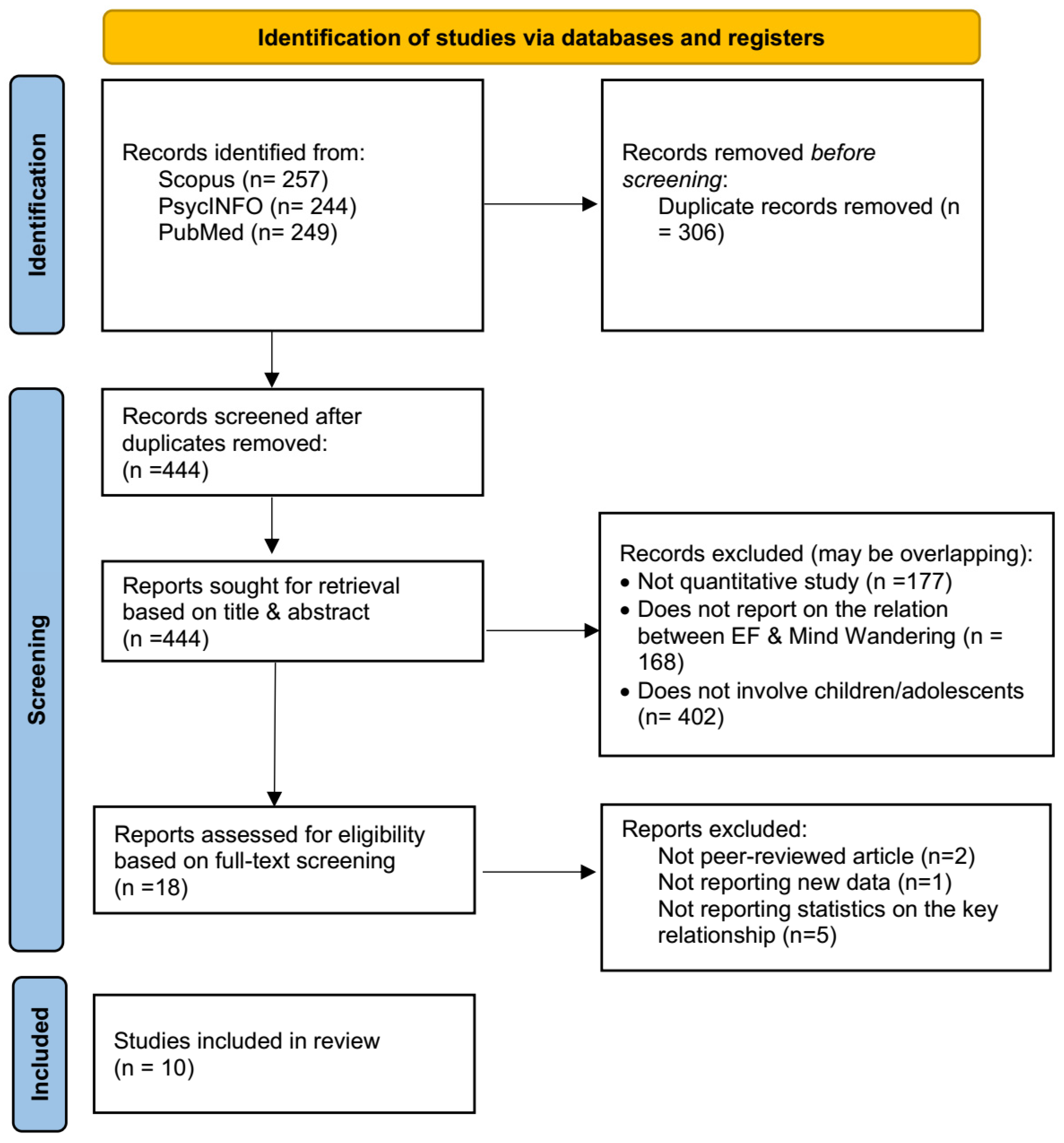

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Charting the Data

3.3. Quality Appraisal

3.4. Synthesis of Findings

3.4.1. Findings from Studies with Children

3.4.2. Findings from Studies with Adolescents

3.4.3. Grouping by Study Type and Robustness of Effect Sizes

4. Discussion

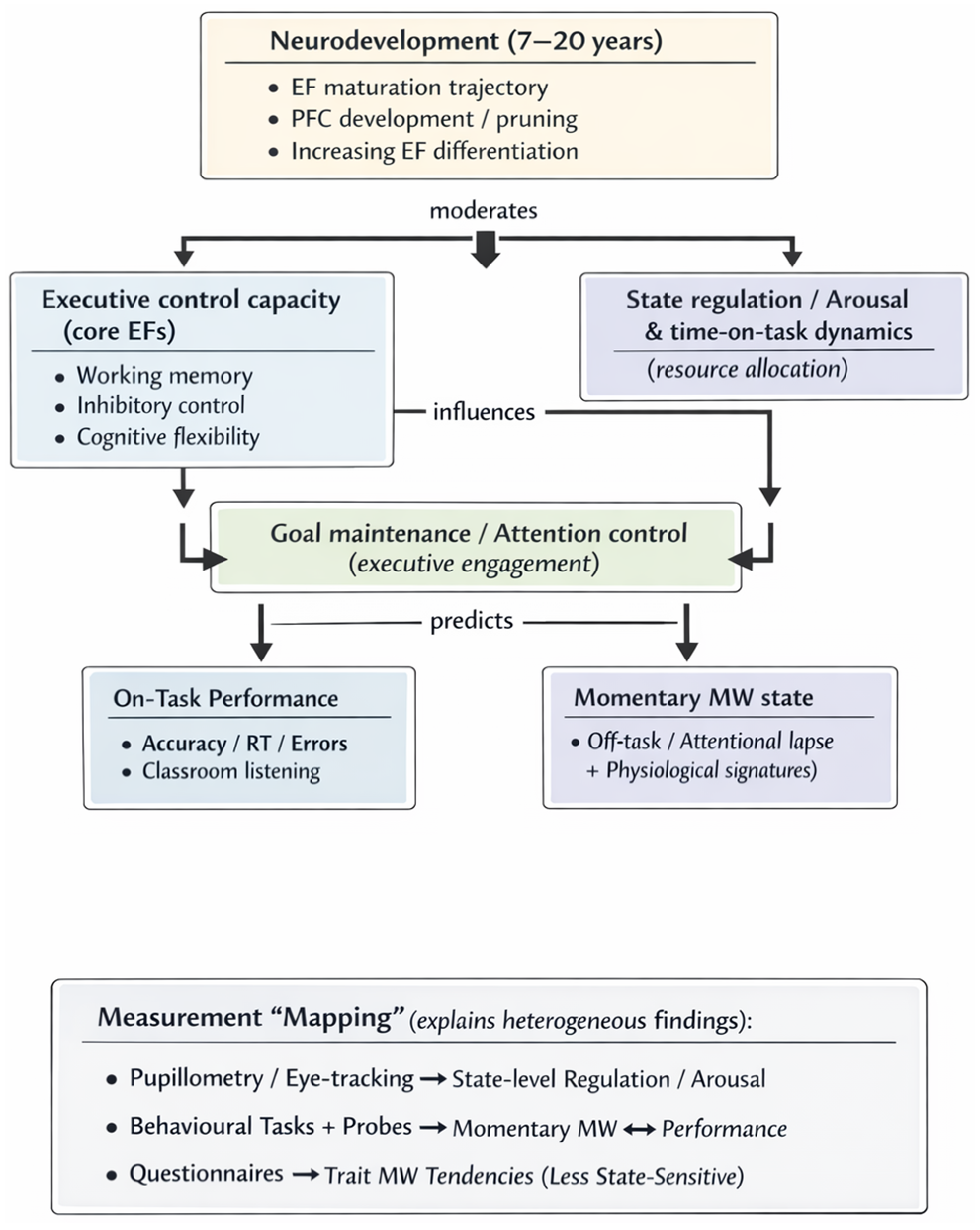

4.1. Executive-Failure Interpretations of MW–EF Associations

4.2. Resource-Control/Dynamic Regulation Lens

4.3. Developmental and Measurement Lens

4.4. Integrating the Findings in a Conceptual Model

4.5. Future Directions for Research and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| WM | working memory |

| MW | mind wandering |

| EFs | executive functions |

| SEM | structural equation modelling |

| RT | reaction time |

References

- Ayasse, N. D., & Wingfield, A. (2020). Anticipatory baseline pupil diameter is sensitive to differences in hearing thresholds. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddeley, A. (2020). Working memory. In A. D. Baddeley, M. W. Eysenck, & M. C. Anderson (Eds.), Memory (3rd ed., pp. 71–111). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S. P., & Barkley, R. A. (2018). Sluggish cognitive tempo. Oxford Textbook of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, J. F., Birney, D. P., & Sternberg, R. J. (2024). A novel approach to measuring an old construct: Aligning the conceptualisation and operationalisation of cognitive flexibility. Journal of Intelligence, 12(6), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, J., Lanier, J., DiSalvo, M., Noyes, E., Fried, R., Woodworth, K. Y., Biederman, I., & Faraone, S. V. (2019). Clinical correlates of mind wandering in adults with ADHD. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 117, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondé, P., Girardeau, J.-C., Sperduti, M., & Piolino, P. (2022). A wandering mind is a forgetful mind: A systematic review on the influence of mind wandering on episodic memory encoding. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 132, 774–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callard, F., Smallwood, J., Golchert, J., & Margulies, D. S. (2013). The era of the wandering mind? Twenty-first century research on self-generated mental activity. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (2019). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J., & Friedman, N. P. (2024). How the brain creates unity and diversity of executive functions. In M. T. Banich, S. N. Haber, & T. W. Robbins (Eds.), The frontal cortex: Organization, networks, and function. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, B. A., & Eriksen, C. W. (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics, 16(1), 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, H. J., Brunsdon, V. E. A., & Bradford, E. E. F. (2021). The developmental trajectories of executive function from adolescence to old age. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghetti, S., Mirandola, C., Angelini, L., Cornoldi, C., & Ciaramelli, E. (2011). Development of subjective recollection: Understanding of and introspection on memory states. Child Development, 82(6), 1954–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacometti Giordani, L., Crisafulli, A., Cantarella, G., Avenanti, A., & Ciaramelli, E. (2023). The role of posterior parietal cortex and medial prefrontal cortex in distraction and mind-wandering. Neuropsychologia, 188, 108639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruberger, M., Simon, E. B., Levkovitz, Y., Zangen, A., & Hendler, T. (2011). Towards a neuroscience of mind-wandering. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartung, J., Engelhardt, L. E., Thibodeaux, M. L., Harden, K. P., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2020). Developmental transformations in the structure of executive functions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 189, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, F., Hart, C. M., Graham, S. A., & Kam, J. W. Y. (2024). Inside a child’s mind: The relations between mind wandering and executive function across 8- to 12-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 240, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F., Shah, H. P., Kam, J. W. Y., & Murias, K. R. (2025). Unraveling the relationship between executive function and mind wandering in childhood ADHD. Child Neuropsychology, 31(5), 791–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, A. V. B., Hart, K. M., Marchak, F. M., & Hutchison, K. A. (2022). Patience is a virtue: Individual differences in cue-evoked pupil responses under temporal certainty. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 84(4), 1286–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C. (2011). Changes and challenges in 20 years of research into the development of executive functions. Infant and Child Development, 20(3), 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. D., & Balota, D. A. (2012). Mind-wandering in younger and older adults: Converging evidence from the sustained attention to response task and reading for comprehension. Psychology and Aging, 27(1), 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2020). Critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies. Joanna Briggs Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, M. J., Meier, M. E., Smeekens, B. A., Gross, G. M., Chun, C. A., Silvia, P. J., & Kwapil, T. R. (2016). Individual differences in the executive control of attention, memory, and thought, and their associations with schizotypy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(8), 1017–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. J., Smeekens, B. A., Meier, M. E., Welhaf, M. S., & Phillips, N. E. (2021). Testing the construct validity of competing measurement approaches to probed mind-wandering reports. Behavior Research Methods, 53(6), 2372–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, W., Hernández, S. P., Rahman, M. S., Voigt, K., & Malvaso, A. (2022). Inhibitory control development: A network neuroscience perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 651547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsantonis, I. (2024). Exploring age-related differences in metacognitive self-regulation: The influence of motivational factors in secondary school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1383118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, I., Hinuma, T., & Tanaka, S. C. (2023). Ecological momentary assessment of mind-wandering: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelbsch, C., Strasser, T., Chen, Y., Feigl, B., Gamlin, P. D., Kardon, R., Peters, T., Roecklein, K. A., Steinhauer, S. R., Szabadi, E., Zele, A. J., Wilhelm, H., & Wilhelm, B. J. (2019). Standards in pupillography. Frontiers in Neurology, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keulers, E. H. H., & Jonkman, L. M. (2019). Mind wandering in children: Examining task-unrelated thoughts in computerized tasks and a classroom lesson, and the association with different executive functions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 179, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kievit, R. A. (2020). Sensitive periods in cognitive development: A mutualistic perspective. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 36, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, S. M., & Rakic, P. (2022). Development of prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(1), 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzeniowski, C., Ison, M. S., & Difabio de Anglat, H. (2021). A summary of the developmental trajectory of executive functions from birth to adulthood. In P. Á. Gargiulo, & H. L. Mesones Arroyo (Eds.), Psychiatry and Neuroscience Update: From Epistemology to Clinical Psychiatry— (Vol. IV, pp. 459–473). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBurnett, K., Villodas, M., Burns, G. L., Hinshaw, S. P., Beaulieu, A., & Pfiffner, L. J. (2014). Structure and validity of sluggish cognitive tempo using an expanded item pool in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(1), 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, D. C. (2019). Measuring Young children’s executive function and self-regulation in classrooms and other real-world settings. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22(1), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2010a). Adrift in the stream of thought: The effects of mind wandering on executive control and working memory capacity. In A. Gruszka, G. Matthews, & B. Szymura (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in cognition (pp. 321–334). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2010b). Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008). Psychological Bulletin, 136, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., & Friedman, N. P. (2012). The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(1), 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari, S., Fitzgerald, P., & Kazemi, R. (2025). The relative accuracy of different methods for measuring mind wandering subtypes: A systematic review. Brain and Behavior, 15(8), e70764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelagatti, C., Blini, E., & Vannucci, M. (2025). Catching mind wandering with pupillometry: Conceptual and methodological challenges. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 16(1), e1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippi, C. L., Bruss, J., Boes, A. D., Albazron, F. M., Deifelt Streese, C., Ciaramelli, E., Rudrauf, D., & Tranel, D. (2021). Lesion network mapping demonstrates that mind-wandering is associated with the default mode network. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 99(1), 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common Method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K. A., Lee, Y., Bovee, E. A., Perez, T., Walton, S. P., Briedis, D., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2019). Motivation in transition: Development and roles of expectancy, task values, and costs in early college engineering. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 1081–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, M. K., Diede, N. T., Nicosia, J., Ball, B. H., & Bugg, J. M. (2022). A multimodal analysis of sustained attention in younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 37(3), 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, M. K., & Unsworth, N. (2019). Pupillometry tracks fluctuations in working memory performance. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81(2), 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouder, J. N., Kumar, A., & Haaf, J. M. (2023). Why many studies of individual differences with inhibition tasks may not localize correlations. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 30(6), 2049–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad, M. A., Ghanavati, E., Rashid, M. H. A., & Nitsche, M. A. (2021). Hot and cold executive functions in the brain: A prefrontal-cingular network. Brain and Neuroscience Advances, 5, 23982128211007769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Smilek, D., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(8), 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V. P. D., Carthery-Goulart, M. T., & Lukasova, K. (2024). Unity and diversity model of executive functions: State of the art and issues to be resolved. Psychology & Neuroscience, 17(4), 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, J. (2013). Distinguishing how from why the mind wanders: A process–occurrence framework for self-generated mental activity. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruyt, K., Herbillon, V., Putois, B., Franco, P., & Lachaux, J.-P. (2019). Mind-wandering, or the allocation of attentional resources, is sleep-driven across childhood. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyer, R., Mayer, A., Geiser, C., & Cole, D. A. (2015). A theory of states and traits—Revised. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11(1), 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tervo-Clemmens, B., Calabro, F. J., Parr, A. C., Fedor, J., Foran, W., & Luna, B. (2023). A canonical trajectory of executive function maturation from adolescence to adulthood. Nature Communications, 14(1), 6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D. R., Besner, D., & Smilek, D. (2015). A resource-control account of sustained attention: Evidence from mind-wandering and vigilance paradigms. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(1), 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, N., & Robison, M. K. (2017). The importance of arousal for variation in working memory capacity and attention control: A latent variable pupillometry study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 43(12), 1962–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unsworth, N., Robison, M. K., & Miller, A. L. (2019). Individual differences in baseline oculometrics: Examining variation in baseline pupil diameter, spontaneous eye blink rate, and fixation stability. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 19(4), 1074–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M., Sosa-Hernandez, L., & Henderson, H. A. (2022). Mind wandering and executive dysfunction predict children’s performance in the metronome response task. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 213, 105257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanesco, A. P., Denkova, E., & Jha, A. P. (2025). Mind-wandering increases in frequency over time during task performance: An individual-participant meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 151(2), 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavagnin, M., Borella, E., & De Beni, R. (2014). When the mind wanders: Age-related differences between young and older adults. Acta Psychologica, 145, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Meng, Y., Li, J., & Shen, X. (2024). Childhood adversity and mind wandering: The mediating role of cognitive flexibility and habitual tendencies. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 15(1), 2301844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search String (Boolean Logic) | Filters Applied | Number of Hits Retrieved 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((“executive function”[MeSH Terms] OR “executive function*”[tiab] OR “working memory”[MeSH Terms] OR “working memory”[tiab] OR “inhibitory control”[tiab] OR “response inhibition”[tiab] OR inhibition[tiab] OR “cognitive flexibility”[tiab] OR “set shifting”[tiab]) AND (“mind wandering”[tiab] OR “spontaneous thought”[tiab] OR “task-unrelated thought”[tiab] OR “off-task thought”[tiab] OR “daydreaming”[tiab])) AND (English[lang]) NOT (“review”[Publication Type] OR “case report”[Publication Type] OR “qualitative”[tiab] OR “meta-analysis”[Publication Type]) | English language, journal article only, empirical | 250 |

| PsycINFO | (DE “Executive Function” OR “executive function*” OR “working memory” OR “inhibitory control” OR “response inhibition” OR “cognitive flexibility” OR “set shifting”) AND (“mind wandering” OR “task-unrelated thought*” OR “spontaneous thought*” OR “off-task thought*” OR “daydreaming”) AND (quantitative OR “statistical analysis” OR correlation OR regression OR experiment* OR “survey” OR “questionnaire” OR “structural equation model*” OR “reaction time” OR “behavioral measure*” OR “performance task”) NOT (DE “Qualitative Research” OR qualitative OR “case study” OR “review”) | English language, journal article only, empirical | 245 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY((“executive function*” OR “working memory” OR “inhibitory control” OR “response inhibition” OR “cognitive flexibility” OR “set shifting) AND (“mind wandering” OR “spontaneous thought*” OR “task-unrelated thought*” OR “off-task thought*” OR “daydreaming”) AND (quantitative OR “statistical analysis” OR correlation OR regression OR experiment* OR “structural equation model*” OR “reaction time” OR “behavioral measure*” OR “performance task”)) | English language, journal article only, empirical | 258 |

| Study | Study Population | Aim(s) of the Study | Methodology | Outcome Measures | Important and Relevant Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Robison & Unsworth, 2019) | Adolescents, university undergraduates (mean age: 19 years) | To examine the associations between WM capacity and pre-trial and task-evoked attention span and task-unrelated thoughts. | Behavioural tasks + pupillometry + self-report; correlational and time-series | WM task accuracy, pre-trial pupil diameter, task-evoked pupil dilation, on/off task probes | WM fluctuations co-occurred with attention span lapses. Smaller pupil diameter and smaller task-evoked responses reflected lapses of goal-directed attention. |

| (Hood et al., 2022) | Adolescents, university undergraduates | To examine whether explicit reminders reduce the WM–Stroop task performance lapses. | Behavioural task + pupillometry + self-report; mixed factorial design | Stroop interference; WM capacity span | Explicit goal reminders reduced the correlation between WM and Stroop-task failure, showing that MW reflects a failure of executive control. |

| (McBurnett et al., 2014) | Children (mean age: 8.66 years old) | To validate and refine the structure of the Sluggish Cognitive Tempo (SCT) task and examine the distinctness of the SCT factors from ADHD symptoms. | Parent and teacher reports; exploratory + confirmatory factor analyses | Parent and teacher-report on the Sluggish Cognitive Tempo task and on ADHD symptoms | Three-factor structure of the SCT task comprising daydreaming, working memory lapses, and sleepiness/tiredness. SCT and ADHD are related yet distinct constructs. |

| (Zhou et al., 2024) | Adolescents, college students (mean age: 19.37 years old) | To examine whether early-life adversity predicts MW and the mediating effect of executive functions in the relationship between early-life adversity and MW. | Self-report scales; serial mediation using SEM | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; Cognitive Flexibility Inventory; Creature of Habit Scale; MW (deliberate and spontaneous) | Control facet of cognitive flexibility negatively predicted mind wandering. Childhood adversity predicted lower perceived control, which predicted more automatic behaviour, which predicted more mind wandering. |

| (Unsworth et al., 2019) | Adolescents, university students (mean age: 19.09 years old) | To examine how baseline oculometric measures relate to EFs, attention control, personality, and MW. | Eye-tracking + behavioural EF tasks + self-report; correlational modelling | Eye metrics, working memory and attentional control tasks, MW, and personality measures | Higher WM, better attention control, and less MW were associated with larger pupil diameter. |

| (Keulers & Jonkman, 2019) | Children (mean age: 10.12 years old) | To examine MW under two conditions: computerised EF task and real-world classroom listening task. To explore links between specific facets of EFs and MW. | Behavioural EF tasks + classroom listening task + self-report probes; cross-context correlational design | Questionnaires on attention-related cognitive errors and mindfulness attention scale; behavioural computerised EF task | MW frequency was similar between computerised and real-world classroom tasks. Inhibition strongly predicted MW. WM was not related to MW. Poor attention switching predicted more MW. |

| (Unsworth & Robison, 2017) | Adolescents, university undergraduates (mean age: 19.48 years old) | To explore how WM and executive attention control relate to off-task thinking and physiological indicators. | Behavioural EF battery + pupillometry + self-report; latent-variable SEM | Executive attention and WM tasks; self-report probes and pupillometric measures | Off-task MW states were related to slower reactions times, reduced accuracy rates, smaller pupil diameters. Off-task thinking predicted lower attention control and WM. |

| (Hasan et al., 2025) | Children (mean age: 9.98 years) | To explore the association between MW and EFs in children with ADHD | Behavioural EF battery + self-report; cross-sectional; regression analyses | Questionnaires on general daydreaming; self-report probes and computerised task | Children with more severe ADHD symptoms and higher WM capacity had few instances of MW. This result was not robust to multiple comparison correction. |

| (Hasan et al., 2024) | Children (mean age: 10.06 years) | To explore the relationship between MW and EFs in children (8 to 12 years old) | Behavioural EF battery + self-report; cross-sectional and regression analyses | Questionnaires on MW; self-report probes and computerised task | 12-year-olds with a greater WM capacity exhibited a lower frequency of MW. Greater inhibitory control was negatively correlated with MW in the 12-year-olds, whereas task switching did not interact with age in predicting MW. |

| (Wilson et al., 2022) | Children (mean age: 7.64 years) | To examine the link between MW during the Metronome Response Task and estimate the relationship between executive dysfunction and MW. | Behavioural EF battery + self-report + parent-report; cross-sectional; multilevel modelling | Questionnaire on executive dysregulation; self-report probes and computerised task | More frequent reports of being on-task rather than MW. Inhibition difficulties, but not WM difficulties, predicted more frequent MW. |

| (Robison & Unsworth, 2019) | (Hood et al., 2022) | (McBurnett et al., 2014) | (Zhou et al., 2024) | (Unsworth et al., 2019) | (Keulers & Jonkman, 2019) | (Unsworth & Robison, 2017) | (Hasan et al., 2025) | (Hasan et al., 2024) | (Wilson et al., 2022) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were objective, standard criteria used for measuring the condition? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were confounding factors identified? | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly | Partly |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Katsantonis, I.G.; Katsantonis, A. Mapping the Relationship Between Core Executive Functions and Mind Wandering in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Intell. 2026, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence14020020

Katsantonis IG, Katsantonis A. Mapping the Relationship Between Core Executive Functions and Mind Wandering in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Journal of Intelligence. 2026; 14(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence14020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatsantonis, Ioannis G., and Argyrios Katsantonis. 2026. "Mapping the Relationship Between Core Executive Functions and Mind Wandering in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review" Journal of Intelligence 14, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence14020020

APA StyleKatsantonis, I. G., & Katsantonis, A. (2026). Mapping the Relationship Between Core Executive Functions and Mind Wandering in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Journal of Intelligence, 14(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence14020020