Creative Self-Efficacy, Academic Performance and the 5Cs of Positive Youth Development in Spanish Undergraduates

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Procedure and Sample Composition

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Data Analysis Design

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

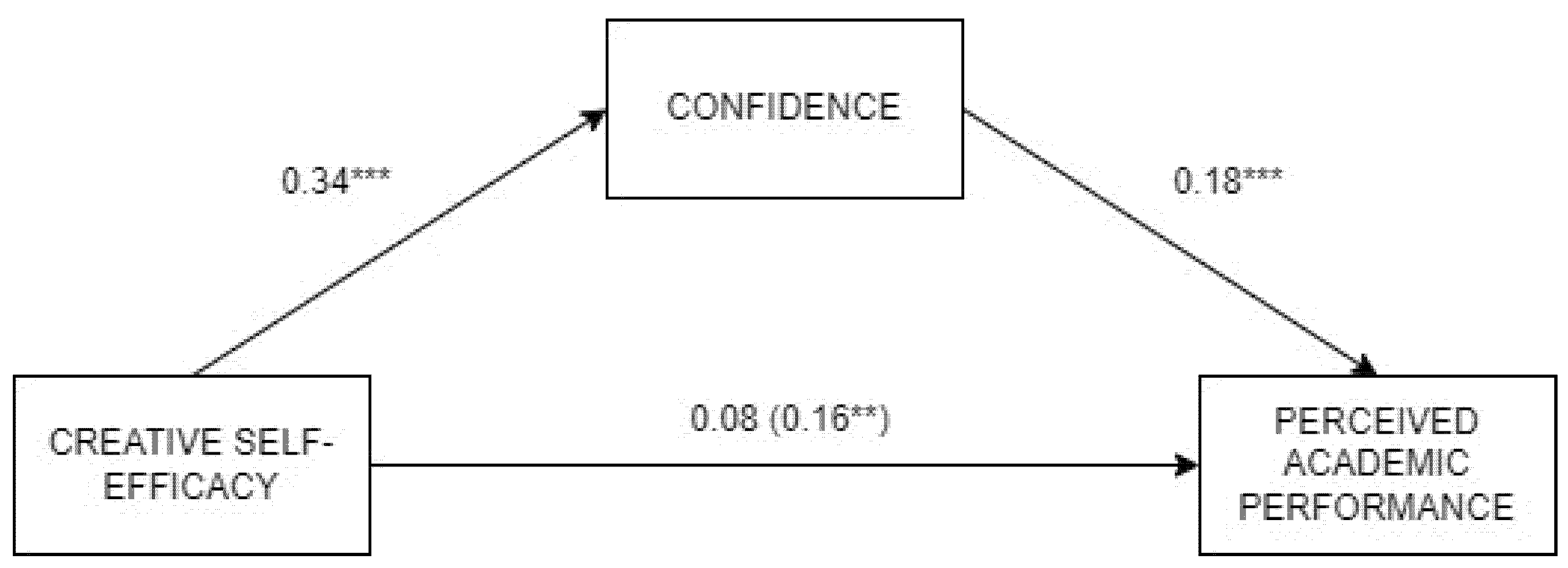

3.2. Regression and Mediation Analyses

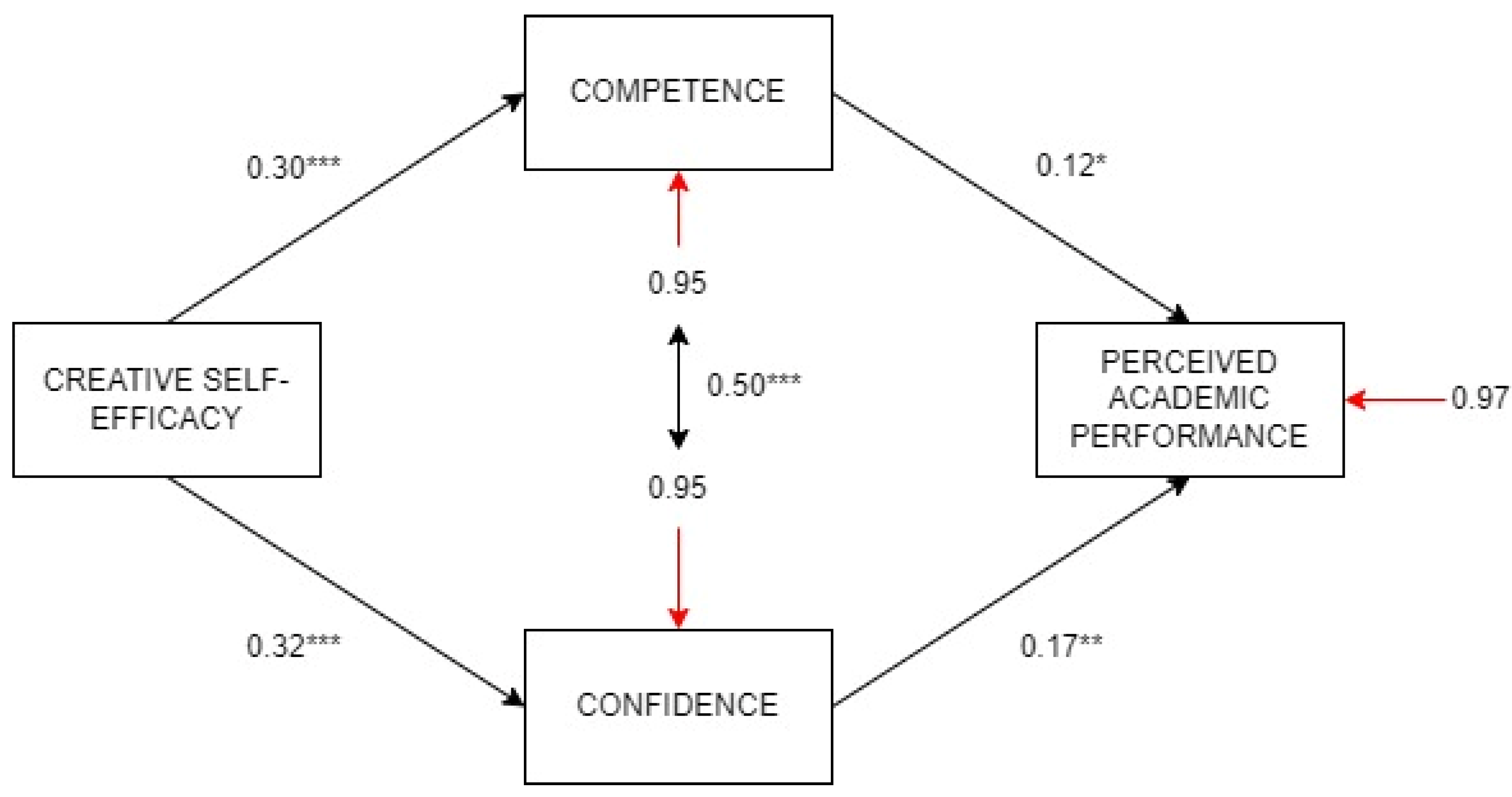

3.3. Structural Equation Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdul Kadir, Nor Ba’yah, Rusyda Helma Mohd, and Radosveta Dimitrova. 2021. Promoting mindfulness through the 7Cs of positive youth development in Malaysia. In Handbook of Positive Youth Development: Advancing Research, Policy, and Practice in Global Contexts. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro Muirhead, Amaranta Consuelo, Rolando Pérez, Matías Dodel, and Amalia Palma. 2024. Determinants of Creativity-Related Skills and Activities Among Young People in Three Latin American Countries. In Social Media, Youth, and the Global South: Comparative Perspectives. Cham: Springer Nature, pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Alt, Dorit, Yoav Kapshuk, and Heli Dekel. 2023. Promoting perceived creativity and innovative behavior: Benefits of future problem-solving programs for higher education students. Thinking Skills and Creativity 47: 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranguren, Maria, and Natalia Irrazabal. 2011. Estudio exploratorio de las propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Autoeficacia Creativa. Revista de Psicología de la Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina 7: 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Mary Elizabeth, and Ryan J. Gagnon. 2020. Positive youth development theory in practice: An update on the 4-H Thriving Model. Journal of Youth Development 15: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, Sarah L., Xu Wang, Daniel S. Quintana, and Anna Abraham. 2022. Predictors of creativity in young people: Using frequentist and Bayesian approaches in estimating the importance of individual and contextual factors. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 16: 209–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, John, and James C. Kaufman. 2008. Gender differences in creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior 42: 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman, vol. 604. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, Marianne, and Nora Wiium. 2019. Promoting academic achievement within a positive youth development framework. Norsk Epidemiologi 28: 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, Ronald A. 2006. Creative self-efficacy: Correlates in middle and secondary students. Creativity Research Journal 18: 447–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, Peter L. 2007. Developmental assets: An overview of theory, research, and practice. In Approaches to Positive Youth Development. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrge, Christian, and Chaoying Tang. 2015. Embodied creativity training: Effects on creative self-efficacy and creative production. Thinking Skills and Creativity 16: 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Barbara M. 2013. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, Aamparo, Bronwyn Laforêt, and PPilar Carrera. 2024. Abstract mindset favors well-being and reduces risk behaviors for adolescents in relative scarcity. Psychology, Society & Education 16: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, Paula, Paulo Vasco, Jose Lopes, Helena Silva, and Eva Morais. 2019. Cooperative learning on promoting creative thinking and mathematical creativity in higher education. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 17: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Margaret H., Steven C. Middleton, Daniel Nguyen, and Lauren K. Zwick. 2014. Mediating relationships between academic motivation, academic integration and academic performance. Learning and Individual Differences 33: 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLiello, Trudy C., and Jeffery D. Houghton. 2008. Creative potential and practised creativity: Identifying untapped creativity in organizations. Creativity and Innovation Management 17: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, Radosveta, and Nora Wiium. 2021. Handbook of Positive Youth Development: Advancing the Next Generation of Research, Policy and Practice in Global Contexts. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Kaiye, Yan Wang, Xuran Ma, Zheng Luo, Ling Wang, and Baoguo Shi. 2020. Achievement goals and creativity: The mediating role of creative self-efficacy. Educational Psychology 40: 1249–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fino, Emanuele, and Siyu Sun. 2022. “Let us create!”: The mediating role of Creative Self-Efficacy between personality and mental well-being in university students. Personality and Individual Differences 188: 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G. John, Edmond P. Bowers, Michelle J. Boyd, Megan K. Mueller, Christopher M. Napolitano, Kristina L. Schmid, Jacqueline V. Lerner, and Richard M. Lerner. 2014. Creation of short and very short measures of the five Cs of positive youth development. Journal of Research on Adolescence 24: 163–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baya, Diego, Ramon Mendoza, Susana Paino, and Margarida Gaspar de Matos. 2017. Perceived emotional intelligence as a predictor of depressive symptoms during mid-adolescence: A two-year longitudinal study on gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences 104: 303–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Jibao, Changqing He, and Hefu Liu. 2017. Supervisory styles and graduate student creativity: The mediating roles of creative self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. Studies in Higher Education 42: 721–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, Jennifer, Eva V. Hoff, Paul H. P. Hanel, and Åse Innes-Ker. 2018. A meta-analysis of the relation between creative self-efficacy and different creativity measurements. Creativity Research Journal 30: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karwowski, Maciej, Izabela Lebuda, and Ewa Wiśniewska. 2018. Measuring creative self-efficacy and creative personal identity. The International Journal of Creativity & Problem Solving 28: 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, James C. 2012. Counting the muses: Development of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS). Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 6: 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomegah, Roger Y. 2007. Predictors of academic performance of university students: An application of the goal efficacy model. College Student Journal 41: 407–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kozina, Ana, Nora Wiium, Jose Michael Gonzalez, and Radosveta Dimitrova. 2019. Positive youth development and academic achievement in Slovenia. Child & Youth Care Forum 48: 223–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Richard M., Jacqueline V. Lerner, and Janette. B. Benson. 2011. Positive youth development: Research and applications for promoting thriving in adolescence. Advances in Child Development and Behavior 41: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, Richard M., Jacqueline V. Lerner, Velma M. Murry, Emilie P. Smith, Edmond P. Bowers, G. John Geldhof, and Mary H. Buckingham. 2021. Positive youth development in 2020: Theory, research, programs, and the promotion of social justice. Journal of Research on Adolescence 31: 1114–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, Richard M., Jun Wang, Paul A. Chase, Akira S. Gutierrez, Elise M. Harris, Rachel O. Rubin, and Ceren Yalin. 2014. Using relational developmental systems theory to link program goals, activities, and outcomes: The sample case of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. New Directions for Youth Development 2014: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin-Bizan, Selva, Edmond P. Bowers, and Richard M. Lerner. 2010. One good thing leads to another: Cascades of positive youth development among American adolescents. Development and Psychopathology 22: 759–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yibing, Neda Bebiroglu, Erin Phelps, Richard M. Lerner, and Jacqueline V. Lerner. 2008. Out-of-school time activity participation, school engagement and positive youth development: Findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. Journal of Youth Development 3: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Lang, Erin Phelps, Jacqueline V. Lerner, and Richard M. Lerner. 2009. Academic competence for adolescents who bully and who are bullied: Findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence 29: 862–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, Gro E., and Kolbjorn S. Bronnick. 2009. Creative self-efficacy: An intervention study. International Journal of Educational Research 48: 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Angie L., and Amber D. Dumford. 2016. Creative cognitive processes in higher education. The Journal of Creative Behavior 50: 282–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeržitski, Stanislav, and Eda Heinla. 2020. Teachers’ creative self-efficacy, self-esteem, and creative teaching in Estonia: A framework for understanding teachers’ creativity-supportive behaviour. Creativity. Theories–Research-Applications 7: 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, Willis F. 2013. A new paradigm for developmental science: Relationism and relational-developmental systems. Applied Developmental Science 17: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Hye-sook, Seokmin Kang, and Sungyeun Kim. 2023. A longitudinal study of the effect of individual and socio-cultural factors on students’ creativity. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1068554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Diaz, Rogelio, and Judith Cavazos-Arroyo. 2018. An exploration of some antecedents and consequences of creative self-efficacy among college students. The Journal of Creative Behavior 52: 256–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Díaz, Rogelio. 2016. Creative self-efficacy: An exploration of its antecedents, consequences, and applied implications. The Journal of Psychology 150: 175–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Ruth, Dennis K. Kinney, Maria Benet, and Ann P. Merzel. 1988. Assessing everyday creativity: Characteristics of the Lifetime Creativity Scales and validation with three large samples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, Ryan, and Roni Reiter-Palmon. 2019. Creative self-efficacy as mediator between creative mindsets and creative problem-solving. The Journal of Creative Behavior 53: 472–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, Mark A., and Garrett J. Jaeger. 2012. The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal 24: 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, Mohd. 2014. Academic anxiety as a correlate of academic achievement. Journal of Education and Practice 5: 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano de Alencar, Eunice M., Denise de Souza Fleith, and Nielsen Pereira. 2017. Creativity in higher education: Challenges and facilitating factors. Temas em Psicologia 25: 553–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, Robert C., Angelicque T. Blackmon, Kimarie Engerman, Leslyn Tonge, and Camille A. McKayle. 2022. Poised for creativity: Benefits of exposing undergraduate students to creative problem-solving to moderate change in creative self-efficacy and academic achievement. Journal of Creativity 32: 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Rachel C., and Eadaoin K. Hui. 2012. Cognitive competence as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal 2012: 210953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, Pamela, and Steven M. Farmer. 2002. Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal 45: 1137–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, Pamela, and Steven M. Farmer. 2011. Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wismath, Shelly, and Maggie Zhong. 2014. Gender differences in university students’ perception of and confidence in problem-solving abilities. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering 20: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Xinfa. 2008. Creativity, Efficacy and Their Organizational Cultural Influences. Ph.D. thesis, Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie der Freien Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Available online: https://refubium.fu-berlin.de (accessed on 2 June 2025).

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.-Creative self-efficacy | 2.99 | 0.51 | (1) | ||||||

| 2.-Academic performance | 3.34 | 0.86 | 0.15 ** | (1) | |||||

| 3.-Character | 3.87 | 0.47 | 0.38 *** | 0.19 *** | (1) | ||||

| 4.-Competence | 2.86 | 0.66 | 0.30 *** | 0.17 ** | 0.22 *** | (1) | |||

| 5.-Confidence | 3.68 | 0.65 | 0.36 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.54 *** | (1) | ||

| 6.-Caring | 4.17 | 0.59 | 0.17 ** | 0.18 *** | 0.39 *** | −0.01 | 0.02 | (1) | |

| 7.-Connection | 3.52 | 0.63 | 0.22 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.13 * | (1) |

| DV: Creative Self-Efficacy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/R2 | β | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Step 1 | 2.48/0.014 | |||

| Gender | 0.10 * | 0.01 | 0.45 | |

| Age | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.23 | |

| Step 2 | 12.41 ***/0.199 | |||

| Gender | 0.11 * | 0.02 | 0.45 | |

| Age | 0.11 * | 0.02 | 0.28 | |

| Character | 0.19 ** | 0.06 | 0.31 | |

| Competence | 0.15 * | 0.04 | 0.27 | |

| Confidence | 0.18 ** | 0.05 | 0.31 | |

| Caring | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.18 | |

| Connection | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.112 | |

| DV: Academic Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/R2 | β | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Step 1 | 1.94/0.011 | |||

| Gender | −0.10 | −0.44 | 0.01 | |

| Age | 0.02 | −0.12 | 0.18 | |

| Step 2 | 4.95 **/0.041 | |||

| Gender | −0.12 * | −0.48 | −0.03 | |

| Age | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.16 | |

| Creative self-efficacy | 0.18 ** | 0.07 | 0.28 | |

| Step 3 | 5.64 ***/0.117 | |||

| Gender | −0.10 | −0.44 | 0.02 | |

| Age | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.21 | |

| Creative self-efficacy | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.17 | |

| Character | −0.01 | −0.14 | 0.12 | |

| Competence | 0.13 * | 0.01 | 0.26 | |

| Confidence | 0.14 * | 0.01 | 0.28 | |

| Caring | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.22 | |

| Connection | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.20 | |

| CONF MEDIATION | PERF R2 = 0.065, CONF R2 = 0.118 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | Z | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Direct effect | ||||||

| CRE->PERF | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.55 | 0.122 | −0.02 | 0.19 |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| CRE->CONF->PERF | 0.07 | 0.02 | 3.42 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Total effect | ||||||

| CRE->PERF | 0.16 | 0.05 | 3.00 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.26 |

| Path coefficients | ||||||

| CONF->PERF | 0.22 | 0.06 | 3.92 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.32 |

| CRE->PERF | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.55 | 0.122 | −0.02 | 0.19 |

| CRE->CONF | 0.34 | 0.05 | 6.99 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.44 |

| COMP MEDIATION | PERF R2 = 0.055, COMP R2 = 0.096 | |||||

| Est | SE | Z | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Direct effect | ||||||

| CRE->PERF | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.80 | 0.072 | −0.01 | 0.21 |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| CRE->COMP->PERF | 0.06 | 0.02 | 2.98 | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.09 |

| Total effect | ||||||

| CRE->PERF | 0.16 | 0.05 | 2.94 | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.26 |

| Path coefficients | ||||||

| COMP->PERF | 0.18 | 0.05 | 3.40 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.29 |

| CRE->PERF | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.80 | 0.072 | −0.01 | 0.21 |

| CRE->COMP | 0.31 | 0.05 | 6.23 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomez-Baya, D.; Garcia-Moro, F.J.; Tomé, G.; Gaspar de Matos, M. Creative Self-Efficacy, Academic Performance and the 5Cs of Positive Youth Development in Spanish Undergraduates. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090120

Gomez-Baya D, Garcia-Moro FJ, Tomé G, Gaspar de Matos M. Creative Self-Efficacy, Academic Performance and the 5Cs of Positive Youth Development in Spanish Undergraduates. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(9):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090120

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomez-Baya, Diego, Francisco Jose Garcia-Moro, Gina Tomé, and Margarida Gaspar de Matos. 2025. "Creative Self-Efficacy, Academic Performance and the 5Cs of Positive Youth Development in Spanish Undergraduates" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 9: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090120

APA StyleGomez-Baya, D., Garcia-Moro, F. J., Tomé, G., & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2025). Creative Self-Efficacy, Academic Performance and the 5Cs of Positive Youth Development in Spanish Undergraduates. Journal of Intelligence, 13(9), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090120