Understanding How Intelligence and Academic Underachievement Relate to Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents with and Without a Migration Background

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. SWB and Life Satisfaction

1.2. Intelligence

1.3. The Relations Between Intelligence and SWB

1.4. The Relations Between Achievement and SWB

1.5. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Study Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Data

2.3.2. Intelligence

2.3.3. Academic Achievement

2.3.4. Underachievement/Overachievement

2.3.5. Life Satisfaction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mean Differences and Bivariate Correlations

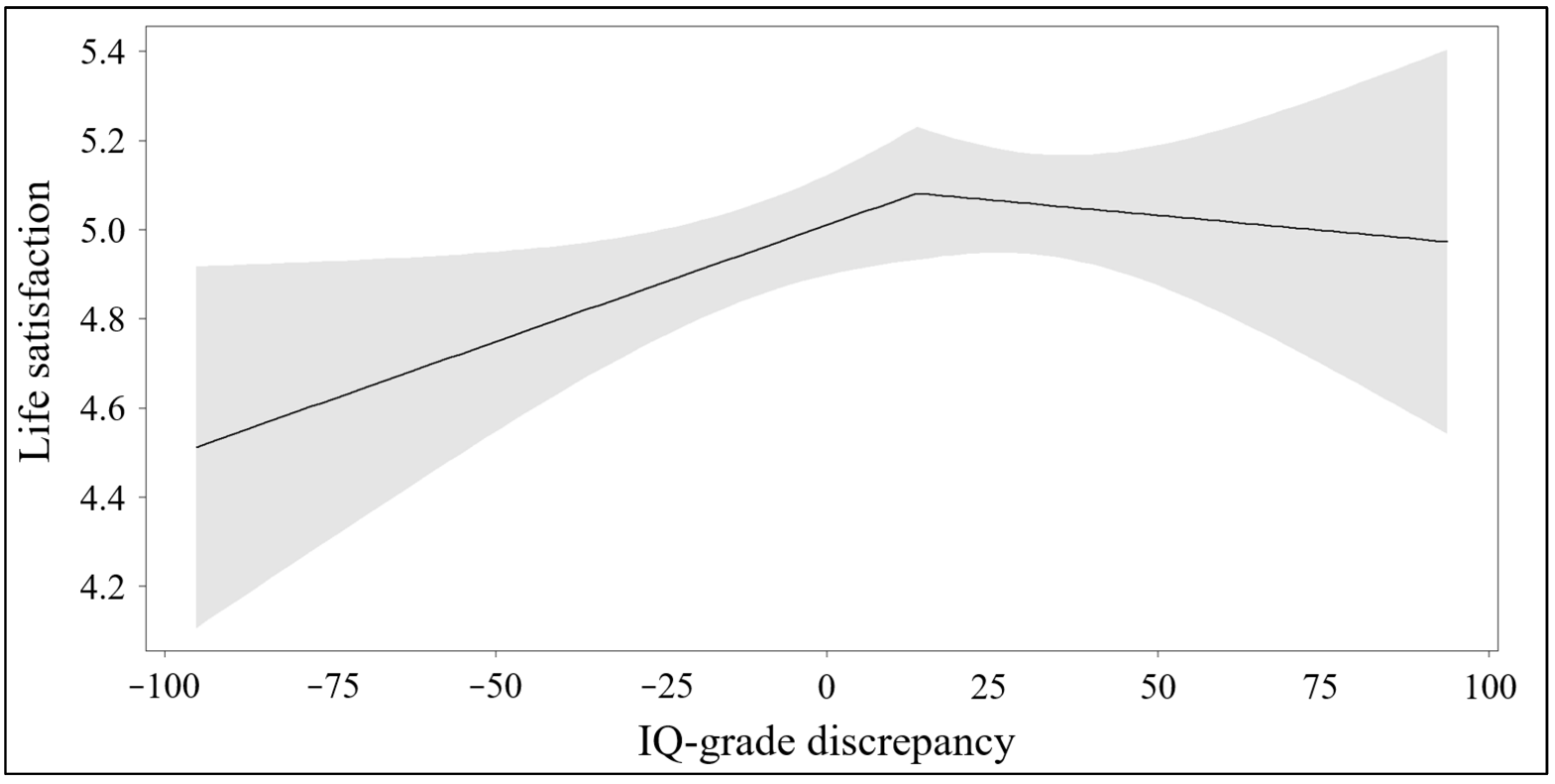

3.2. Segmented Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SWB | Subjective Well-Being |

| GLS | General Life Satisfaction Scale |

References

- Ali, Afia Gareth Ambler, Andre Strydom, Dheeraj Rai, Claudia Cooper, Sally McManus, Scott Weich, Howard Meltzer, Simon Dein, and Angela Hassiotis. 2013. The relationship between happiness and intelligent quotient: The contribution of socio-economic and clinical factors. Psychological Medicine 43: 1303–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alieva, Aigul, Vincent A. Hildebrand, and Philippe Van Kerm. 2024. The progression of achievement gap between immigrant and native-born students from primary to secondary education. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 92: 100961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zoubi, Samer M., and Mohammad A. Bani Younes. 2015. Low Academic Achievement: Causes and Results. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 5: 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, Jürgen, and Gundel Schümer. 2001. Familiäre Lebensverhältnisse, Bildungsbeteiligung und Kompetenzerwerb [Family living conditions, participation in education and skills acquisition]. In PISA 2000. Basiskompetenzen von Schülerinnen und Schülern im Internationalen Vergleich. Edited by Jürgen Baumert, Eckhard Klieme, Michael Neubrand, Manfred Prenzel, Ulrich Schiefele, Wolfgang Schneider, Petra Stanat, Klaus-Jürgen Tillmann and Manfred Weiß. Opladen: Leske und Budrich, pp. 323–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, Martin, and Filip Fors Connolly. 2019. The association between life satisfaction and affective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology 73: 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadouria, Nitu Singh, and Dipal Patel. 2025. The Influence of Self-Esteem, Subjective Well-Being and Teacher Relationship on Academic Success Among UG and PG Students. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 28: 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluemink, Chris, Tessa Jenniskens, Annemarie van Langen, Bianca Leest, and Maarten H. J. Wolbers. 2024. Underachievement among disadvantaged pupils in Dutch primary education. Irish Educational Studies, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, Bruce A., and E. F. Brown. 2006. Behavioral Identification and Assessment of Gifted and Talented Students. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 24: 112–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, Razia Syeda, and Jahan Sarwat Khanam. 2017. Relationship of academic performance and well-being in University Students. Pakistan Journal of Medical Research 56: 126–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bücker, Susanna, Sevim Nuraydin, Bianca A. Simonsmeier, Michael Schneider, and Maike Luhmann. 2018. Subjective well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality 74: 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, Trent N., and Tzu-Jung Lin. 2022. Psychological Well-Being of Intellectually and Academically Gifted Students in Self-Contained and Pull-Out Gifted Programs. Gifted Child Quarterly 66: 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, Maurice, Frans Lelie, Elif Keskiner, Laure Michon, and Ismintha Waldring. 2023. How do people without migration background experience and impact today’s superdiverse cities? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49: 1937–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbert, Claudia. 2002. HSWBS. Habituelle subjektive Wohlbefindensskala [Verfahrensdokumentation, Autorenbeschreibung und Fragebogen]. In Open Test Archive. Edited by Leibniz-Institut für Psychologie (ZPID). Trier: ZPID. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, Jesus Alfonso D., and Ronnel B. King. 2018. Subjective well-being is reciprocally associated with academic engagement: A two-wave longitudinal study. Journal of School Psychology 69: 100–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. 1984. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 95: 542–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Edward. 2023. Happiness: The science of subjective well-being. In Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. Edited by Robert Biswas-Diener and Ed Diener. Champaign: DEF Publishers. Available online: http://noba.to/qnw7g32t (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Giota, Joanna, and Jan-Eric Gustafsson. 2017. Perceived Demands of Schooling, Stress and Mental Health: Changes from Grade 6 to Grade 9 as a Function of Gender and Cognitive Ability. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress 33: 253–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottfredson, Linda S. 1997. Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography. Intelligence 24: 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, Linda S. 2008. Of what value is intelligence? In WISC-IV Clinical Assessment and Intervention, 2nd ed. Edited by Aurelio Prifitera, Donald H. Saklofske and Lawrence G. Weiss. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 545–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, Jan-Eric. 1984. A unifying model for the structure of intellectual abilities. Intelligence 8: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, Jan-Eric. 1988. Hierarchical models of individual differences in cognitive abilities. In Advances in the Psychology of Human Intelligence. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., vol. 4, pp. 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, Anthony, and Yael Brinbaum. 2014. Unequal Attainments: Ethnic Educational Inequalities in Ten Western Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the British Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Rahmi Luke, and Jae Yup Jung. 2022. The identification of gifted underachievement: Validity evidence for the commonly used methods. The British Journal of Educational Psychology 92: 1133–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, Satoshi. 2014. Why is intelligence associated with stability of happiness? British Journal of Psychology 105: 316–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Metin, and Cahit Erdem. 2021. Students’ Well-Being and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis Study. Child Indicators Research 14: 1743–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkcaldy, Bruce, Adrian Furnham, and Georg Siefen. 2004. The Relationship Between Health Efficacy, Educational Attainment, and Well-Being Among 30 Nations. European Psychologist 9: 107–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapp, Thea, Alli Klapp, and Jan-Eric Gustafsson. 2023. Relations between students’ well-being and academic achievement: Evidence from Swedish compulsory school. European Journal of Psychology of Education 39: 275–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Kit-Ling, and David W. Chan. 2001. Identification of underachievers in Hong Kong: Do different methods select different underachievers? Educational Studies 27: 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Ashley D., E. Scott Huebner, Patrick S. Malone, and Robert F. Valois. 2011. Life satisfaction and student engagement in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 40: 249–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, Jose, and Emily Long. 2021. A global decline in adolescents’ subjective well-being: A comparative study exploring patterns of change in the life satisfaction of 15-year-old students in 46 countries. Child Indicators Research 14: 1251–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueggo, Vito M. R. 2008. Segmented: An R package to fit regression models with broken-line relationships. R News 8: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Neihart, Maureen. 1999. The impact of giftedness on psychological well-being: What does the empirical literature say? Roeper Review 22: 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisser, Ulric, Gwyneth Boodoo, Thomas J. Bouchard, Jr., A. Wade Boykin, Nathan Brody, Stephen J. Ceci, Diane F. Halpern, John C. Loehlin, Robert Perloff, Robert J. Sternberg, and et al. 1996. Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns. American Psychologist 51: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Zi Jia, E. Scott Huebner, and Kimberly J. Hills. 2015. Life Satisfaction and Academic Performance in Early Adolescents: Evidence for Reciprocal Association. Journal of School Psychology 53: 479–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, Carol, Ed Diener, and Norbert Schwarz. 2011. Positive Affect and College Success. Journal of Happiness Studies 12: 717–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeier, Ramona, Gerda Hagenauer, and Michaela Gläser-Zikuda. 2021. Who feels good in school? Exploring profiles of scholastic well-being in secondary-school students and the effect on achievement. International Journal of Educational Research Open 2: 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2017. PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Student’s Well-Being. Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, Carmel, P. Alex Linley, and John Maltby. 2010. Very Happy Youths: Benefits of Very High Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents. Social Indicators Research 98: 519–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangvid, Beatrice Schindler. 2007. Sources of Immigrants’ Underachievement: Results from PISA—Copenhagen. Education Economics 15: 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, Sally M., and D. Betsy McCoach. 2000. The Underachievement of Gifted Students: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? Gifted Child Quarterly 44: 152–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roksa, Josipa, and Peter Kinsley. 2019. The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Research in Higher Education 60: 415–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Netzer, Pninit, and Ricardo Tarrasch. 2024. The path to life satisfaction in adolescence: Life orientations, prioritizing, and meaning in life. Current Psychology 43: 16591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerter, Jakob, Justine Stang-Rabrig, Ruben Kleinkorres, Johannes Bleher, Philipp Doebler, and Nele McElvany. 2024. Importance of students’ social resources for their academic achievement and well-being in elementary school. European Journal of Psychology of Education 39: 4515–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecki, Karen L., Elliot M. Tucker-Drob, Shigehiro Oishi, and Timothy A. Salthouse. 2008. Life satisfaction across adulthood: Different determinants at different ages? The Journal of Positive Psychology 3: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprong, Stefanie, and Jan Skopek. 2022. Academic achievement gaps by migration background at school starting age in Ireland. European Societies 24: 580–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang-Rabrig, JustineJakob Schwerter, Matthew Witmer, and Nele McElvany. 2023. Beneficial and negative factors for the development of students’ well-being in educational context. Current Psychology 42: 31294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt [Federal Statistical Office]. 2017. Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit. Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund. Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2016 [Population and Employment. Population with a Migration Background. Results of the 2016 Microcensus]. Fachserie 1, Reihe 2.2. Wiesbaden: Federal Statistical Office. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmayr, Ricarda, Josi Michels, and Anne Franziska Weidinger. 2017. Studie: FA(IR)BULOUS—Faire Beurteilung des Leistungspotenzials von Schülerinnen und Schülern [Study: FA(IR)BULOUS—Fair Assessment of Pupils’ Performance Potential]. Dortmund: TU Dortmund. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmayr, Ricarda, Julia Crede, Nele McElvany, and Linda Wirthwein. 2015. Subjective Well-Being, Test Anxiety, Academic Achievement: Testing for Reciprocal Effects. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Gonneke W. J. M., Maartje Boer, Peter F. Titzmann, Alina Cosma, and Sophie D. Walsh. 2020. Immigration status and bullying victimization: Associations across national and school contexts. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 66: 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, Shannon M., and E. Scott Huebner. 2006. Is extremely high life satisfaction during adolescence advantageous? Social Indicators Research 78: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, Shannon M., Emily J. Shaffer, and Kristen N. Riley. 2008. A social-cognitive-behavioral model of academic predictors of adolescents’ life satisfaction. School Psychology Quarterly 23: 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, Shannon M., Kristen N. Riley, and Emily J. Shaffer. 2006. Academic Correlates of Children and Adolescents’ Life Satisfaction. School Psychology International 27: 567–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, Chana, and Moshe Tatar. 2001. Psychological adjustment among Israeli adolescent immigrants: A report on life satisfaction, self-concept, and self-esteem. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 30: 449–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Batenburg-Eddes, Tamara, and Jelle Jolles. 2013. How does emotional wellbeing relate to underachievement in a general population sample of young adolescents: A neurocognitive perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 27: 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, Ruth. 2012. Happiness: Also Known as “Life Satisfaction” and “Subjective Well-Being”. In Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Research. Edited by Kenneth C. Land, Alex C. Michalos and M. Joseph Sirgy. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, Ruth, and Yowon Choi. 2012. Does intelligence boost happiness? Smartness of all pays more than being smarter than others. International Journal of Happiness and Development 1: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieno, Alessio, Massimo Santinello, Michela Lenzi, Daniela Baldassari, and Massimo Mirandola. 2009. Health status in immigrants and native early adolescents in Italy. Journal of Community Health 34: 181–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, Oliver, Gesa Ramm, Karin Zimmer, Heike Heidemeier, and Manfred Prenzel. 2006. PISA 2003-Kompetenzen von Jungen und Mädchen mit Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland. Ein Problem ungenutzter Potentiale? [PISA 2003 competences of boys and girls with a migration background in Germany. A problem of unutilised potential?]. Unterrichtswissenschaft 34: 146–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watten, Reidulf G., Jon Lars Syversen, and Trond Myhrer. 1995. Quality of life, intelligence and mood. Social Indicators Research 36: 287–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, Rudolf H. 2019. CFT 20-R mit WS/ZF-R. Grundintelligenztest Skala 2—Revision mit Wortschatztest und Zahlenfolgentest—Revision (2. Überarbeitete Auflage mit Aktualisierten und Erweiterten Normen). Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

| Descriptive Statistics | Correlation Coefficients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Range | Empirical Range | M (SD) | IQ | Grade Average | IQ-Grade Discrepancy | |

| Life satisfaction | 1.0; 7.0 | 1.1; 7.0 | 5.0 (1.2) | −0.04 | −0.08 * | 0.08 * |

| Intelligence | - | 57.0; 148.0 | 98.1 (14.1) | −0.27 *** | −0.59 *** | |

| Grade average (not inverted) | 1.0; 6.0 | 1.0; 5.7 | 3.1 (0.7) | −0.57 *** | ||

| IQ-grade discrepancy | −100.0; 100.0 | −95.3; 93.8 | 7.0 (34.6) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neumann, A.; Steinmayr, R.; Roth, M.; Altmann, T. Understanding How Intelligence and Academic Underachievement Relate to Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents with and Without a Migration Background. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090105

Neumann A, Steinmayr R, Roth M, Altmann T. Understanding How Intelligence and Academic Underachievement Relate to Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents with and Without a Migration Background. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(9):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090105

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeumann, Alicia, Ricarda Steinmayr, Marcus Roth, and Tobias Altmann. 2025. "Understanding How Intelligence and Academic Underachievement Relate to Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents with and Without a Migration Background" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 9: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090105

APA StyleNeumann, A., Steinmayr, R., Roth, M., & Altmann, T. (2025). Understanding How Intelligence and Academic Underachievement Relate to Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents with and Without a Migration Background. Journal of Intelligence, 13(9), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090105