Dissociable Effects of Verbalization on Solving Insight and Non-Insight Problems

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Predominantly Conscious Processes

1.2. Predominantly Unconscious Processes

1.3. Controversial Effects of Verbalization

2. Experiment

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

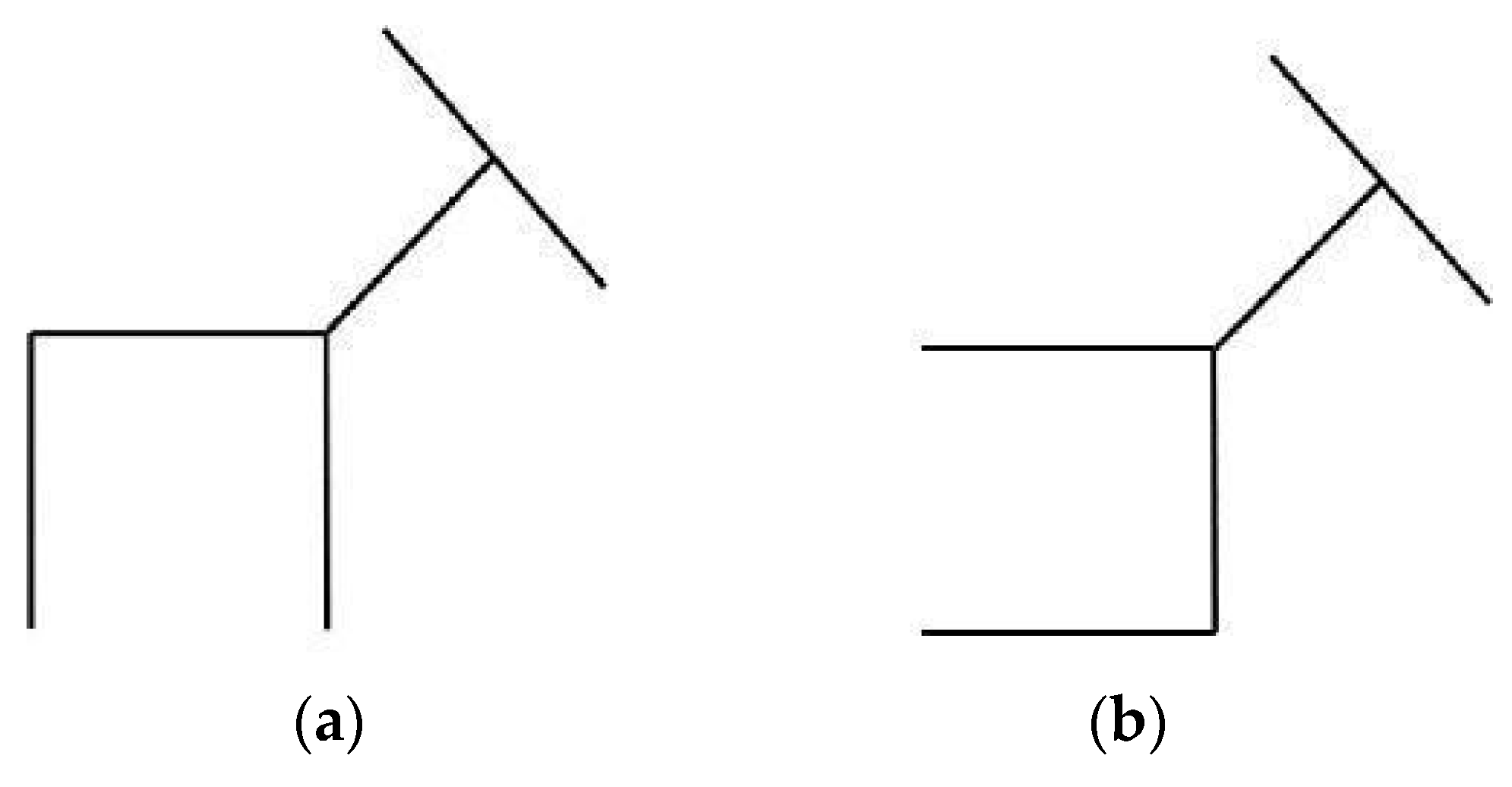

3.2. Materials

3.3. Analysis

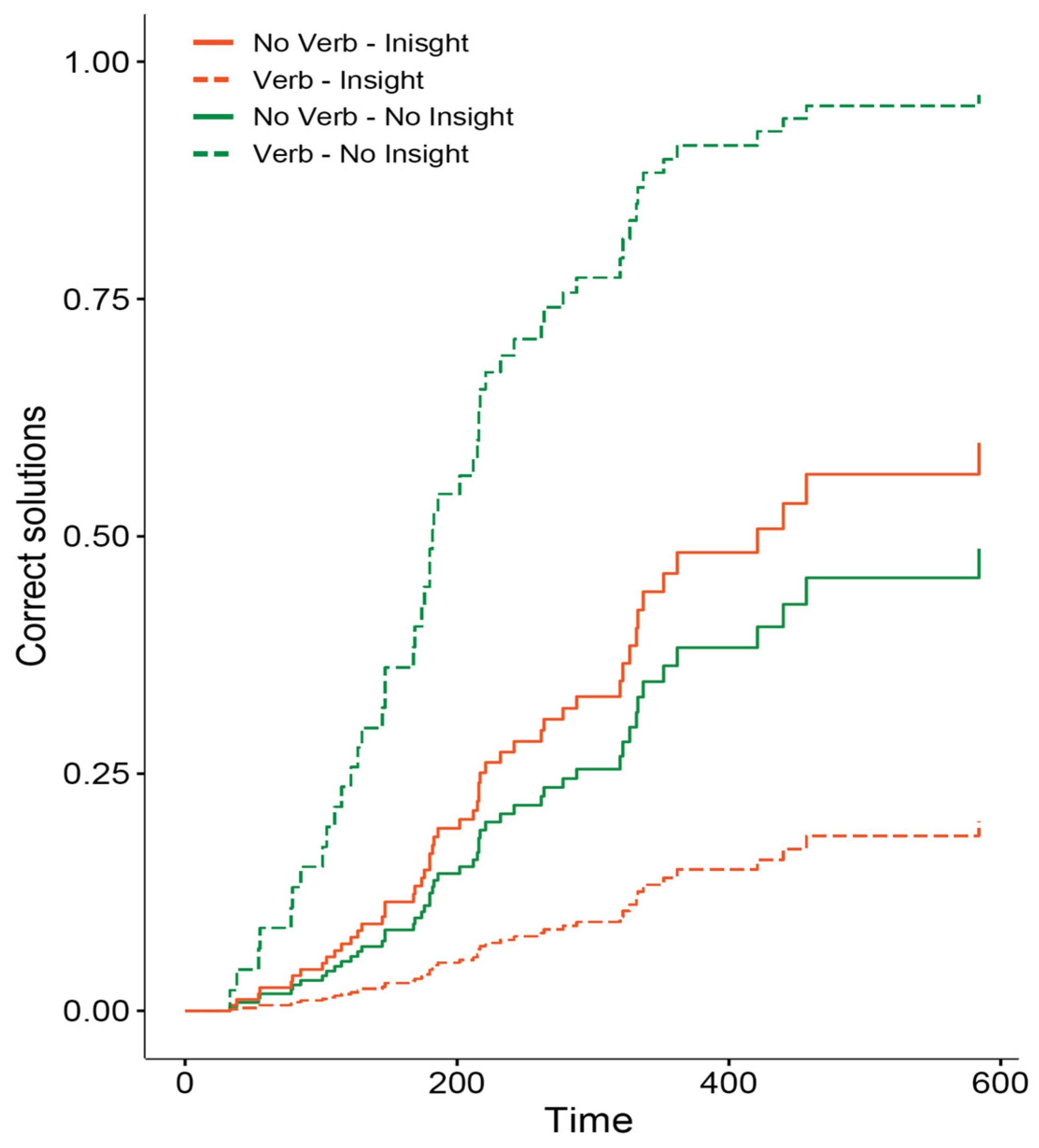

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | On the contrary, the low-demanding task required only a routinary mechanical procedure, leaving cognitive resources available at the unconscious level to solve the insight problem. This task resulted in the best performance (response rate and resolution time), thus confirming that insight problem resolution depended on an unconscious and analytical process. |

References

- Bagassi, Maria, and Laura Macchi. 2016. The interpretative function and the emergence of unconscious analytic thought. In Cognitive Unconscious and Human Rationality. Edited by Laura Macchi, Maria Bagassi and Riccardo Viale. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Linden J., John E. Marsh, Damien Litchfield, Rebecca L. Cook, and Natalie Booth. 2015. When distraction helps: Evidence that concurrent articulation and irrelevant speech can facilitate insight problem solving. Thinking & Reasoning 21: 76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Ivana, Erika Branchini, Roberto Burro, Elena Capitani, and Ugo Savardi. 2020. Overtly prompting people to “think in opposites” supports insight problem solving. Thinking & Reasoning 26: 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, Edward M., Mark Jung-Beeman, Jessica Fleck, and John Kounios. 2005. New approaches to demystifying insight. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9: 322–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caravona, Laura, and Laura Macchi. 2022. Different incubation tasks in insight problem solving: Evidence for unconscious analytic thought. Thinking & Reasoning 29: 559–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chronicle, Edward P., James N. MacGregor, and Thomas C. Ormerod. 2004. What makes an insight problem? The roles of heuristics, goal conception, and solution recoding in knowledge-lean problems. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 30: 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chuderski, Adam, and Jan Jastrzębski. 2018. Much ado about aha!: Insight problem solving is strongly related to working memory capacity and reasoning ability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 147: 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, David Roxbee, and David Oakes. 1984. Analysis of Survival Data. New York: CRC Press, vol. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Danek, Amory H., Jennifer Wiley, and Michael Öllinger. 2016. Solving classical insight problems without aha! experience: 9 dot, 8 coin, and matchstick arithmetic problems. The Journal of Problem Solving 9: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCaro, Marci S., and Mareike B. Wieth. 2016. When higher working memory capacity hinders insight. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 42: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K. Anders, and Herbert Alexander Simon. 1984. Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fedor, Anna, Eörs Szathmáry, and Michael Öllinger. 2015. Problem solving stages in the five square problem. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, Jessica I., and Robert W. Weisberg. 2004. The use of verbal protocols as data: An analysis of insight in the candle problem. Memory and Cognition 32: 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, Jessica I., and Robert W. Weisberg. 2013. Insight versus analysis: Evidence for diverse methods in problem solving. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 25: 436–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhooly, Kenneth J., Evie Fioratou, and Nigel Henretty. 2010. Verbalization and problem solving: Insight and spatial factors. British Journal of Psychology 101: 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilhooly, Kenneth J., Linden J. Ball, and Laura Macchi, eds. 2018. Creativity and Insight Problem Solving. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-50069-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Beeman, Mark, Edward M. Bowden, Jason Haberman, Jennifer L. Frymiare, Stella Arambel-Liu, Richard Greenblatt, Paul J. Reber, and John Kounios. 2004. Neural activity when people solve verbal problems with insight. Public Library of Science Biology 2: e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, Craig A., and Herbert A. Simon. 1990. In search of insight. Cognitive Psychology 22: 374–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, Trina C., and Stellan Ohlsson. 2004. Multiple causes of difficulty in insight: The case of the nine-dot problem. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 30: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblich, Günther, Stellan Ohlsson, and Gary E. Raney. 2001. An eye movement study of insight problem solving. Memory and Cognition 29: 1000–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblich, Günther, Stellan Ohlsson, Hilde Haider, and Detlef Rhenius. 1999. Constraint relaxation and chunk decomposition in insight problem solving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 25: 1534–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, Laura, and Maria Bagassi. 2012. Intuitive and analytical processes in insight problem solving: A psycho-rhetorical approach to the study of reasoning. Mind & Society 11: 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Macchi, Laura, and Maria Bagassi. 2015. When analytic thought is challenged by a misunderstanding. Thinking and Reasoning 21: 147–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, Janet, and David Wiebe. 1987. Intuition in insight and noninsight problem solving. Memory & Cognition 15: 238–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson, Stellan. 1992. Information-processing explanations of insight and related phenomena. In Advances in the Psychology of Thinking. Edited by Mark T. Keane and Kenneth J. Gilhooly. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, vol. 1, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson, Stellan. 2011. Deep Learning: How the Mind Overrides Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Öllinger, Michael, Gary Jones, and Günther Knoblich. 2006. Heuristics and representational change in two-move matchstick arithmetic tasks. Advances in Cognitive Psychology 2: 239–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, David. 1981. The Mind’s Best Work. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon-Mordekovich, Nirit, and Mark Leikin. 2023. Insight problem solving is not that special, but business is not quite’as usual’: Typical versus exceptional problem-solving strategies. Psychological Research 87: 1995–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schooler, Jonathan W., Stellan Ohlsson, and Kevin Brooks. 1993. Thoughts beyond words: When language overshadows insight. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 122: 166–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuyck, Hans, Axel Cleeremans, and Eva Van den Bussche. 2022. Aha! under pressure: The Aha! experience is not constrained by cognitive load. Cognition 219: 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therneau, Terry. 2024. A Package for Survival Analysis in R. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Weisberg, Robert W. 2006. Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg, Robert W. 2015. Toward an integrated theory of insight in problem solving. Thinking and Reasoning 21: 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, George Y., Michael P. Osborne, Qinggang Diao, and Qiqing Yu. 2017. Piecewise Cox models with right-censored data. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation 46: 7894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No Verbalization | Verbalization | |

|---|---|---|

| Insight problem | 57% | 13% |

| Non-insight problem | 30% | 80% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macchi, L.; Poli, F.; Caravona, L. Dissociable Effects of Verbalization on Solving Insight and Non-Insight Problems. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13030036

Macchi L, Poli F, Caravona L. Dissociable Effects of Verbalization on Solving Insight and Non-Insight Problems. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(3):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacchi, Laura, Francesco Poli, and Laura Caravona. 2025. "Dissociable Effects of Verbalization on Solving Insight and Non-Insight Problems" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 3: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13030036

APA StyleMacchi, L., Poli, F., & Caravona, L. (2025). Dissociable Effects of Verbalization on Solving Insight and Non-Insight Problems. Journal of Intelligence, 13(3), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13030036