From Evidence to Insight: An Umbrella Review of Computational Thinking Research Syntheses

Abstract

1. Introduction

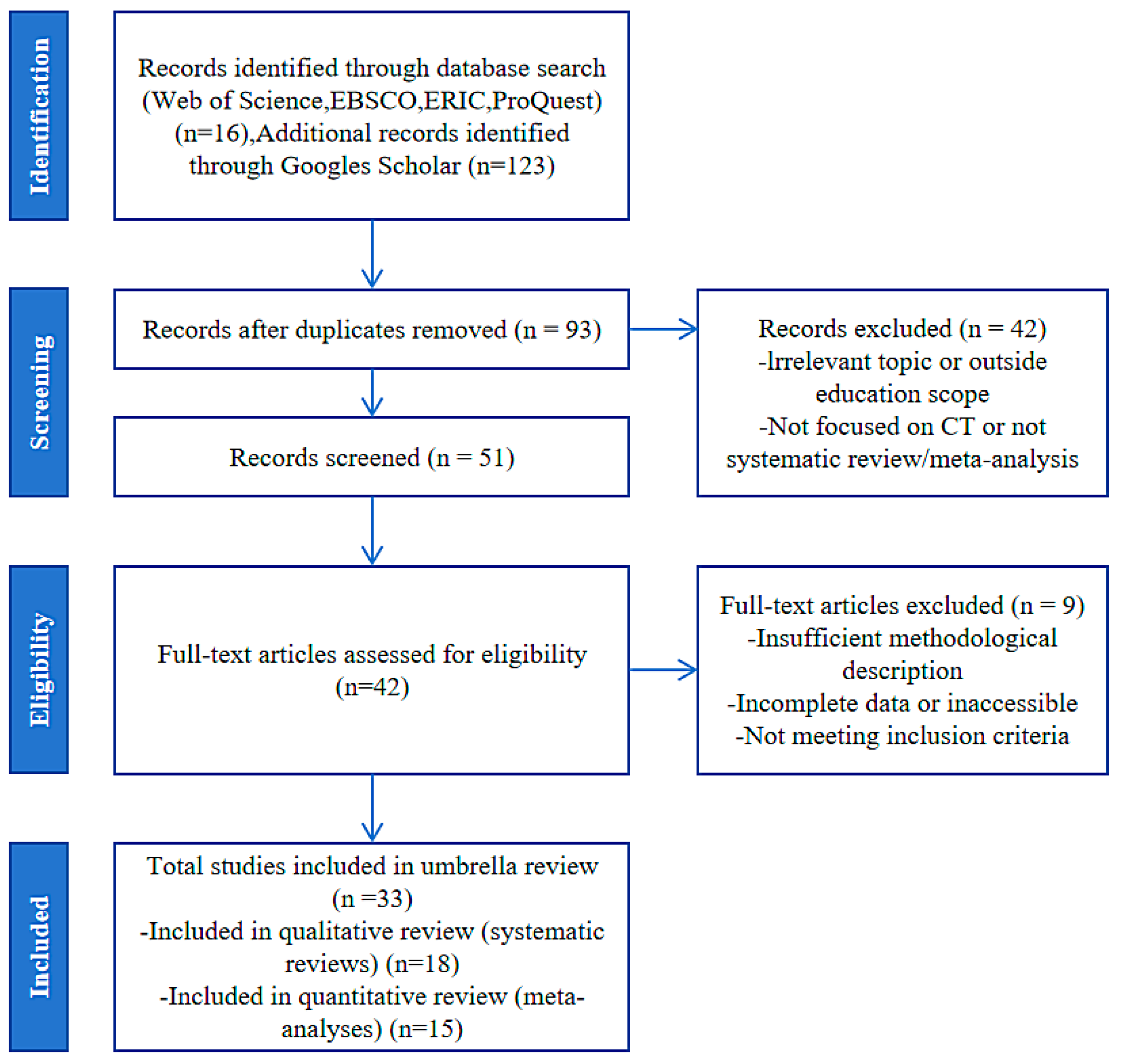

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Analysis

2.1.1. Data Interpretation

2.1.2. Quality Evaluation

2.1.3. Evaluation of Heterogeneity Between Studies

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Quality and Overall Trends of Included Studies

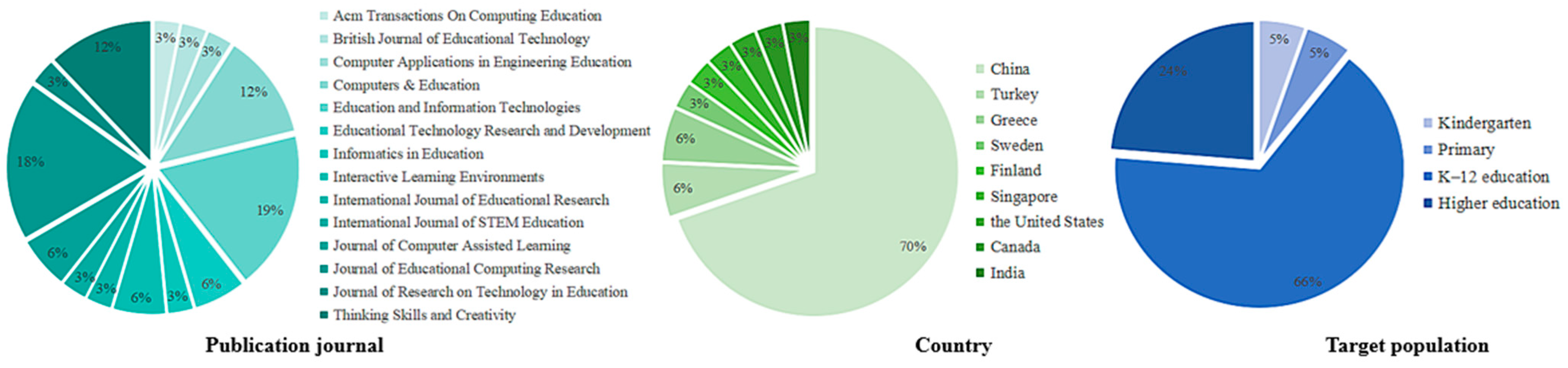

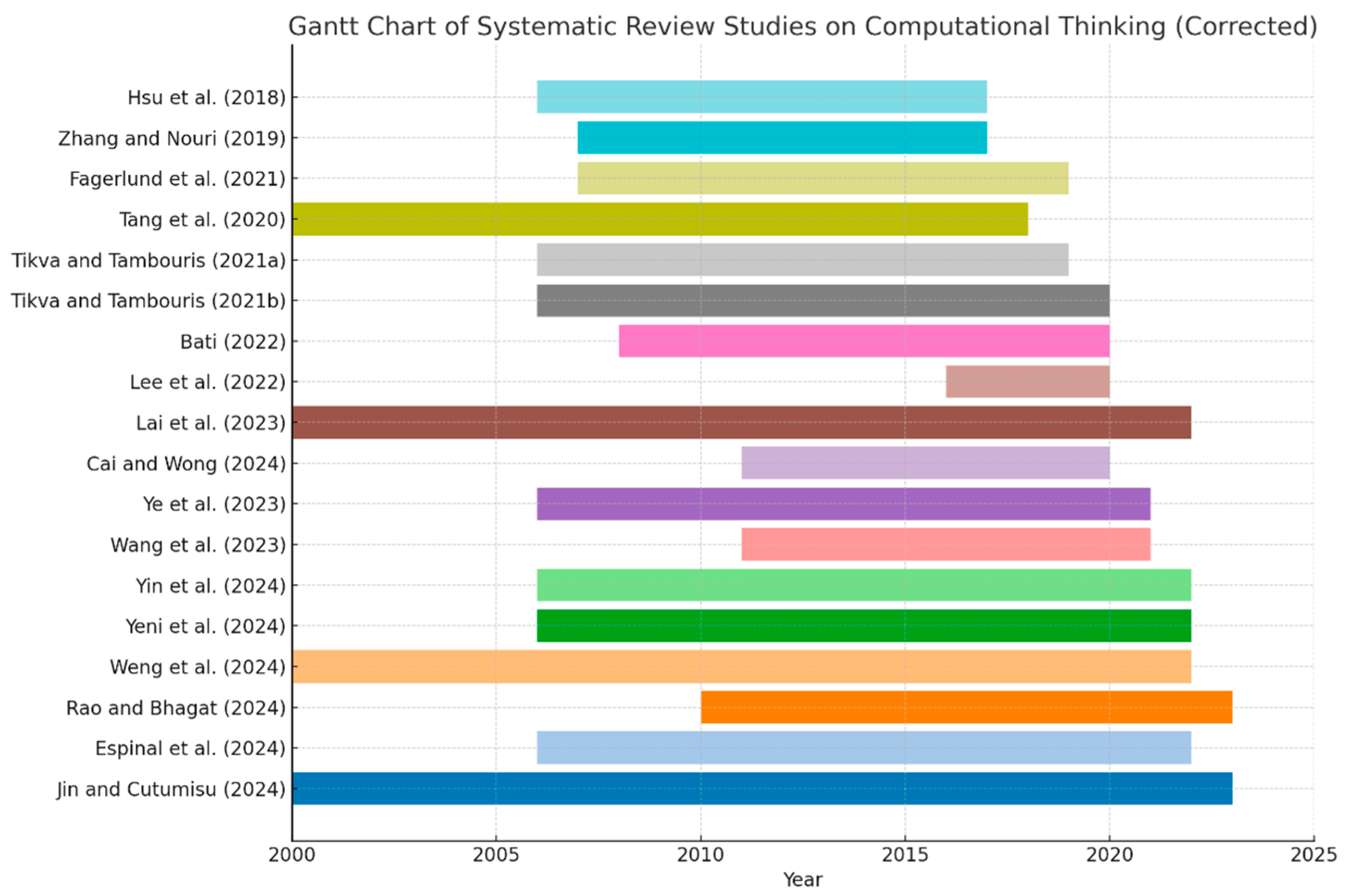

3.1.1. Descriptive Characteristics of Included Studies

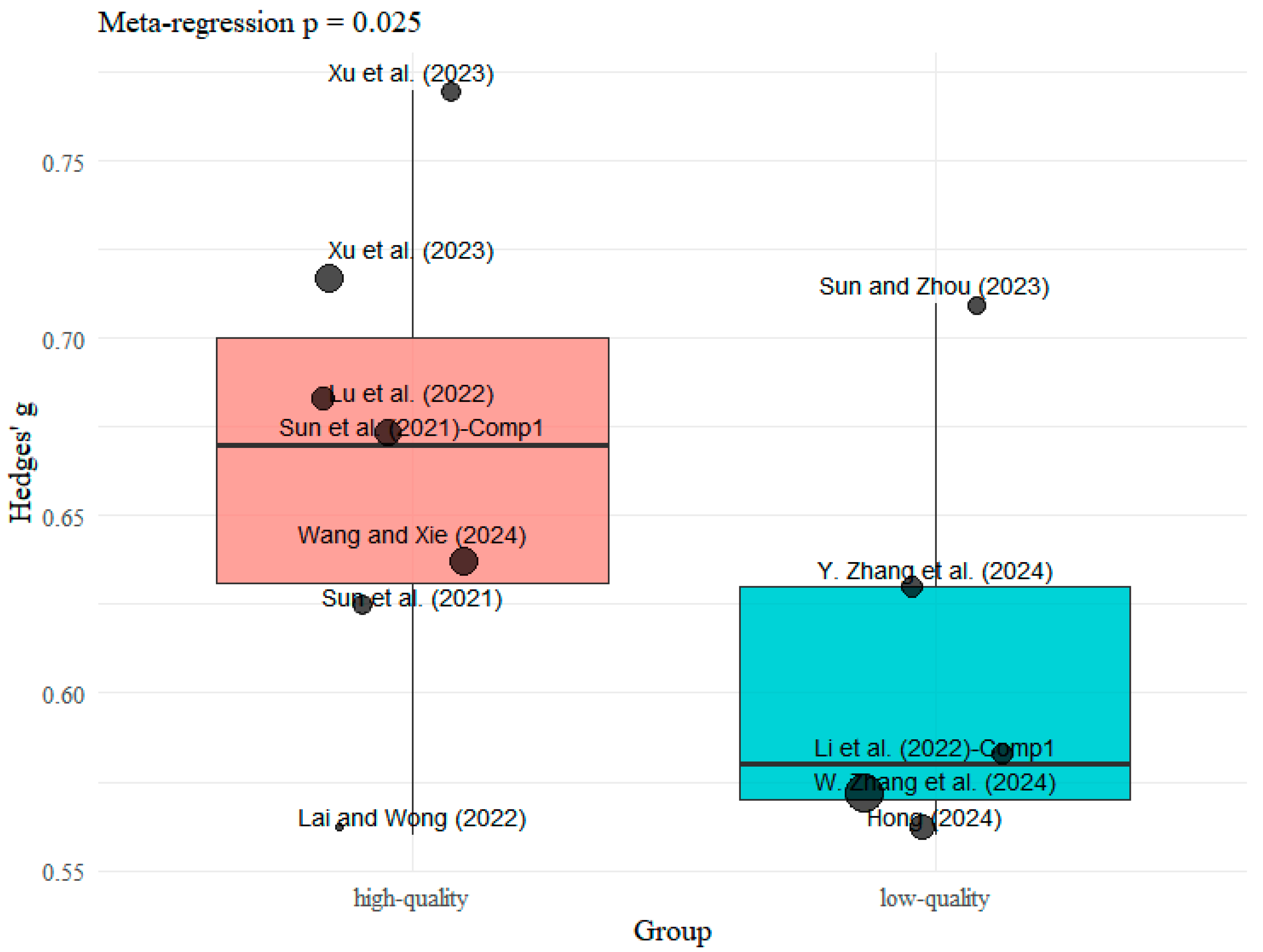

3.1.2. Quality Evaluation of Included Studies

3.1.3. Statistical Analysis of Overall Research Trends

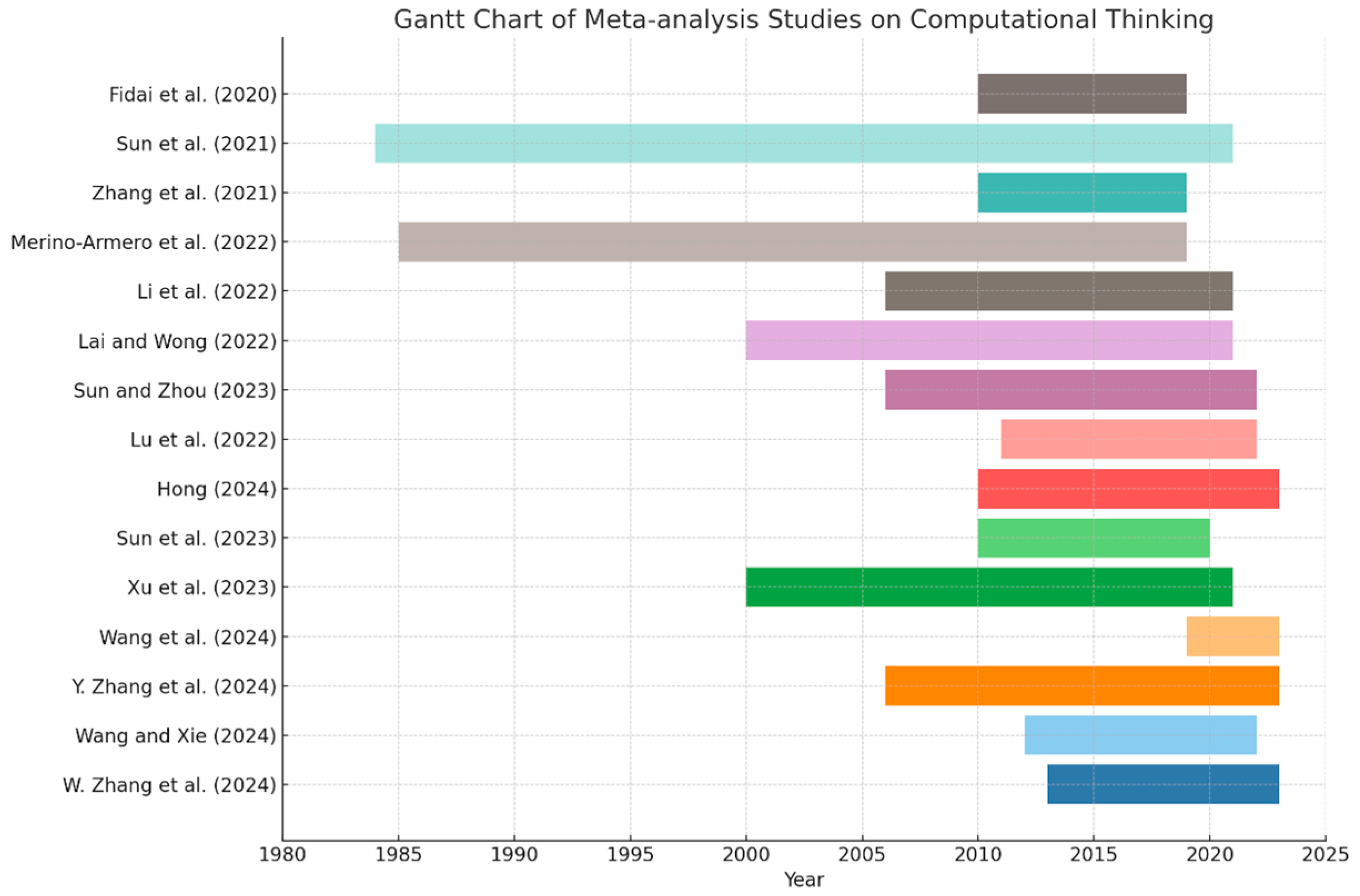

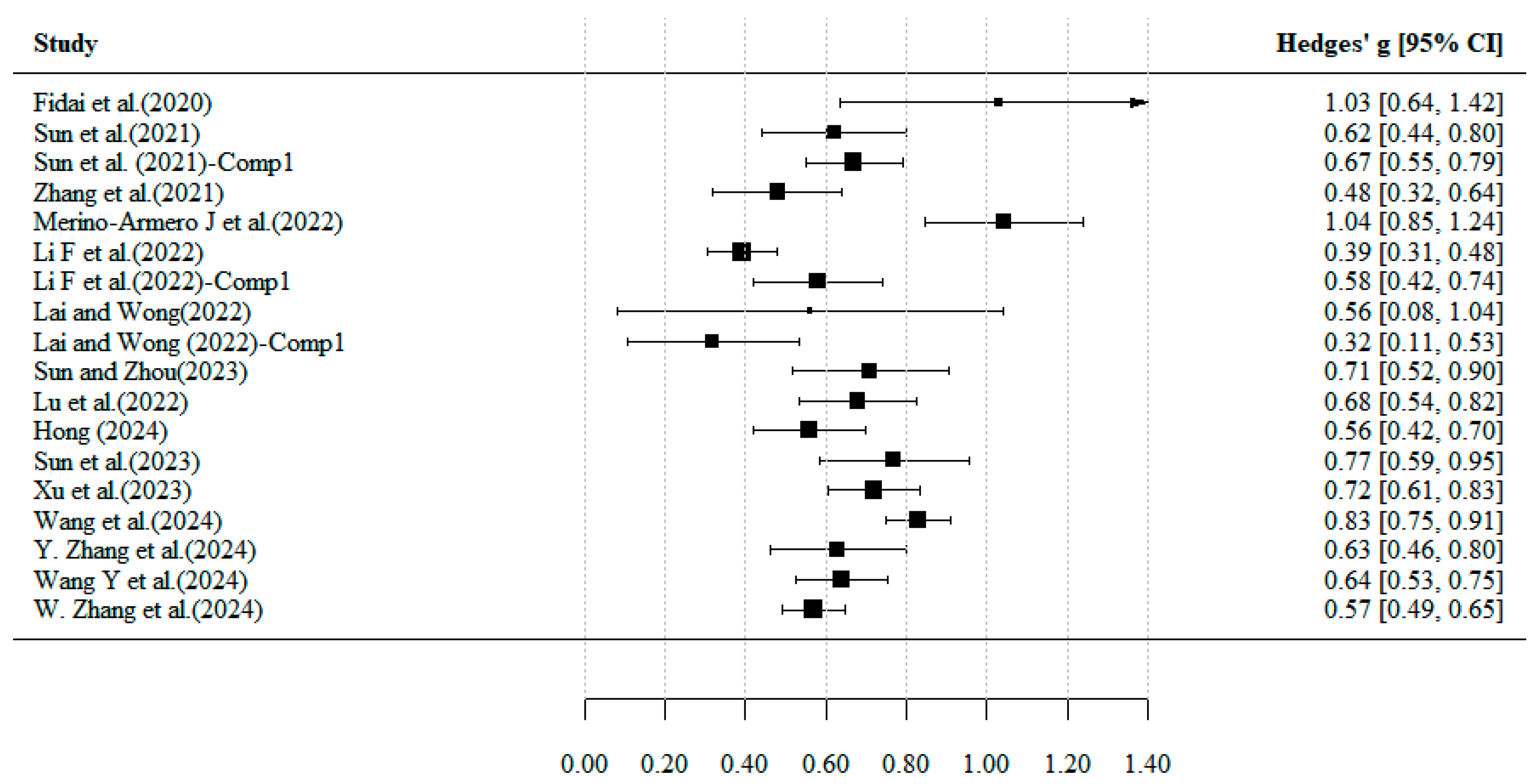

3.2. Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses

3.2.1. Intervention Strategies in CT Education

3.2.2. Moderating Variables in CT Interventions

- Learner characteristics

- Intervention design

- Instructional tools

- Assessment methods

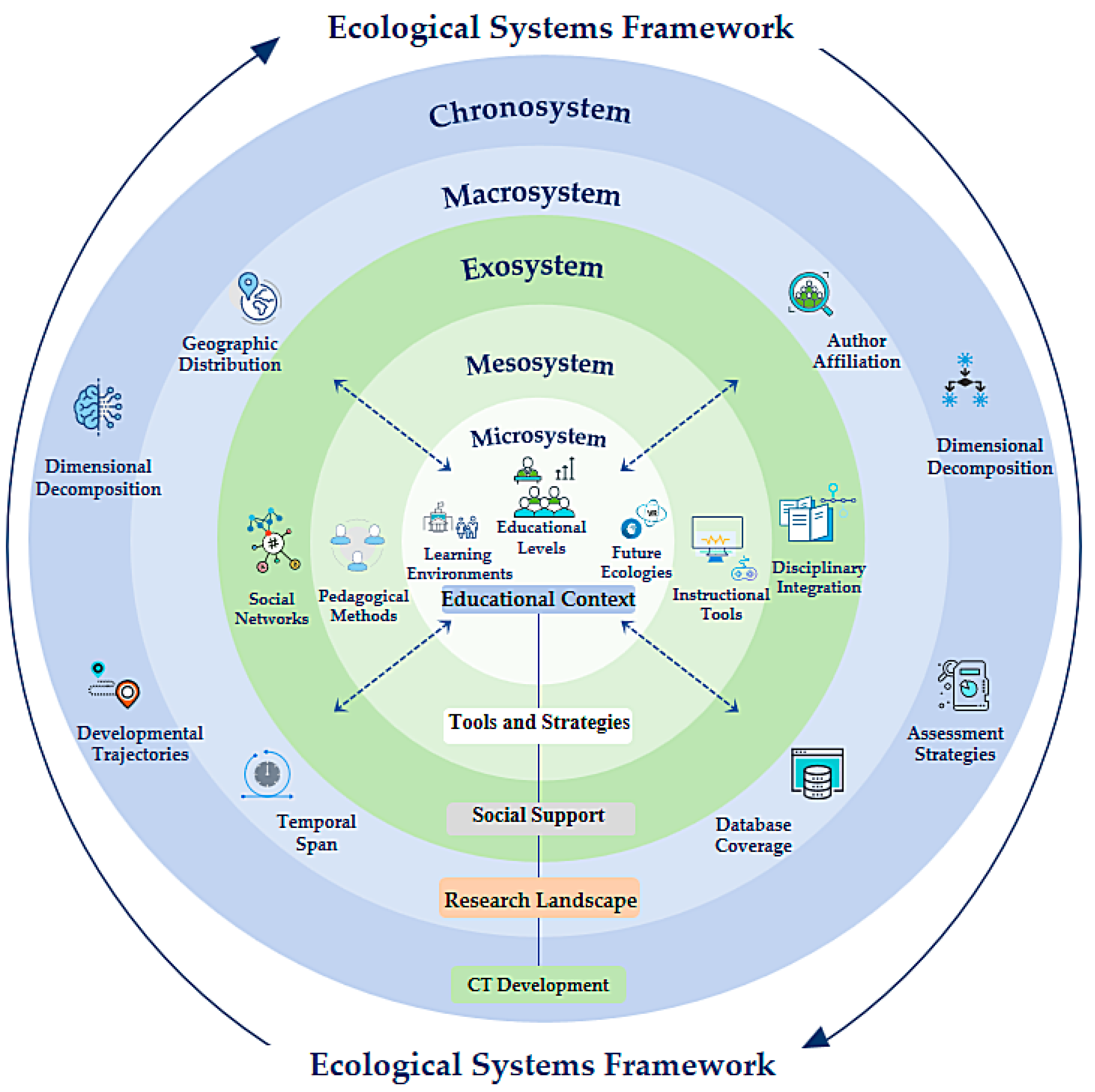

3.3. Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews

3.3.1. Microsystem

3.3.2. Mesosystem

3.3.3. Exosystem

3.3.4. Macrosystem

3.3.5. Chronosystem

4. Discussion and Limitations

4.1. What Is the Quality of Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews Related to CT, and What Overall Trends Do They Reflect?

4.2. How Effective Are Different Types of CT Intervention Strategies, and What Key Moderating Variables Influence Their Outcomes?

4.3. How Are Factors Influencing CT Development Distributed Across System Ecological Levels (Individual, Micro, Meso, Exo, Macro)?

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Authors (Year) | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 | A9 | A10 | A11 | A12 | A13 | A14 | A15 | A16 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (Y), No (N) | Yes (Y), Partial Yes (PY), No (N) | Y, N | Y, PY, N | Y, N | Y, N | Y, PY, N | Y, PY, N | Y, PY, N | Y, N | Y, N | Y, N | Y, N | Y, N | Y, N | Y, N | 0–16 | ||

| 1 | Fidai et al. (2020) | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11.5 |

| 2 | Sun et al. (2021) | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 13.5 |

| 3 | Zhang et al. (2021) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 13 |

| 4 | Merino-Armero et al. (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | PY | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 11.5 |

| 5 | Li et al. (2022) | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | 10 |

| 6 | Lai and Wong (2022) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| 7 | Sun and Zhou (2023) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| 8 | Lu et al. (2022) | Y | N | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 10.5 |

| 9 | Hong (2024) | Y | N | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| 10 | Sun et al. (2023) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| 11 | Xu et al. (2023) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| 12 | Wang et al. (2024) | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | PY | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| 13 | Zhang et al. (2024b) | N | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | PY | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| 14 | Wang and Xie (2024) | Y | N | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 10.5 |

| 15 | Zhang et al. (2024a) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| ID | Authors (Year) | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 | A9 | A10 | A16 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (Y), No (N) | Yes (Y), Partial Yes (PY), No (N) | Y, N | Y, PY, N | Y, N | Y, N | Y, PY, N | Y, PY, N | Y, PY, N | Y, N | Y, N | 0–11 | ||

| 1 | Hsu et al. (2018) | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | 4 |

| 2 | Zhang and Nouri (2019) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | 5 |

| 3 | Fagerlund et al. (2021) | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | 4 |

| 4 | Tang et al. (2020) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | 6 |

| 5 | Tikva and Tambouris (2021a) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 6 |

| 6 | Tikva and Tambouris (2021b) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | 6 |

| 7 | Bati (2022) | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 5 |

| 8 | Lee et al. (2022) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | 6 |

| 9 | Lai et al. (2023) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | 6 |

| 10 | Cai and Wong (2024) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | 6 |

| 11 | Ye et al. (2023) | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | PY | N | N | Y | 4.5 |

| 12 | Wang et al. (2023) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | PY | N | N | Y | 5.5 |

| 13 | Yin et al. (2024) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | 6 |

| 14 | Yeni et al. (2024) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | 6 |

| 15 | Weng et al. (2024) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | 6 |

| 16 | Rao and Bhagat (2024) | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 5 |

| 17 | Espinal et al. (2024) | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | 4 |

| 18 | Jin and Cutumisu (2024) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | 6 |

| ID | Authors (Year) | Database | Time Span | Number of Studies | Number of Effect Sizes | Total Sample Size | Moderator Variables | Independent Variables | Outcome Variables | Effect Size Type | Effect Size | Confidence Interval | p Value | Q (P-Value) | I-squared | Publication Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fidai et al. (2020) | ERIC, PsyCINFO, Web of Science, LearnTechLib | 2010–2019 | 12 | 29 | 584 | grade level, study duration | Arduino-based interventions | CT skills | Cohen’s d | 1.03 | [0.630, 1.420] | <0.001 | 40.85 (0.000) | 87.32% | Y |

| 2 | Sun et al. (2021) | ScienceDirect, Spring, Web of Science | 1984–2021 | 54 | 114 | 11,827 | Subject, Sample size, Intervention duration, Programming activity forms, Programming instruments, Assessment types | Solo programming | CT skills | Hedges’ g | 0.622 | [0.442, 0.801] | <0.001 | 854.321 (0.000) | 86.77% | Y |

| 60 | Collaborative programming | 0.670 | [0.060, 0.552] | <0.001 | Y | |||||||||||

| 3 | Zhang et al. (2021) | Web of Science, ERIC, IEEE, ScienceDirect, Springer Link | 2010–2019 | 6 | 6 | 930 | Gender, Grade Levels, Experimental Periods | Educational Robots | CT skills | SMD | 0.48 | [0.32, 0.64] | <0.001 | NA | 86.00% | Y |

| 4 | Merino-Armero et al. (2022) | Web of Science Core Collection, ProQuest, ERIC, PubMed, EBSCO, etc. | before 2020 | 41 | 61 | 3852 | Educational level, Educational area, Kind of intervention, Type of learning tool, Assessment tool, Framework used, Session length, Intervention length, Intervention intensity, CT dimension worked | CT education | CT skills | Cohen’s d | 1.044 | [0.849, 1.238] | <0.001 | 375.5 (0.000) | 86% | Y |

| 5 | Li et al. (2022) | Web of Science, EBSCO, Taylor & Francis, ScienceDirect, Springer | 2006–2021 | 29 | 31 | 2764 | Grade level, Interdisciplinary course, Experiment duration | Unplugged activities | CT skills | Hedges’ g | 0.392 | [0.308, 0.475] | <0.001 | 86.138 (0.000) | 83.75% | Y |

| Programming exercises | 0.576 | [0.408, 0.734] | <0.001 | Y | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Lai and Wong (2022) | ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, ERIC, Scopus | 2000–2021 | 33 | 220 | 4717 | Educational level, Programming environment, Duration of study, Grouping method, Group size, Educational level | Collaborative problem solving | CT skills | Hedges’ g | 0.562 | [0.08–1.04] | <0.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Individual problem solving | 0.316 | [0.10–0.53] | <0.001 | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||||

| 7 | Sun and Zhou (2023) | ScienceDirect, Spring and Web of Science | 2006–2022 | 19 | 37 | NA | Education level, Intervention duration, Text-based Programming Environment, Assessment tools, Sample size | Text-based programming | CT skills | Hedges’ g | 0.71 | [0.51, 0.90] | <0.001 | 176.05 (0.000) | 82.22% | Y |

| 8 | Lu et al. (2022) | EBSCO, Web of Science, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, CNKI, WanFang DATA | 2011–2022 | 24 | 28 | 2134 | Game type, Intervention duration, Grade level, Instrument type | Game-based learning | CT skills | Hedges’ g | 0.677 | [0.532, 0.821] | <0.001 | 117.264 (0.000) | 76.98% | Y |

| 9 | Hong (2024) | Web of Science, ERIC, SpringerLink, EBSCOhost, IEEE, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar | 2010–2023 | 27 | 36 | NA | Grade Levels, Teaching styles, Participation methods, Experimental cycles, Sample size | Educational robots | CT skills | SMD | 0.558 | [0.419,0.697] | <0.001 | 149.608 (0.000) | 76.61% | Y |

| 10 | Xu et al. (2023) | Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar | 2010–2020 | 22 | 39 | NA | Sample size, Grade level, Game usage mode, Game tool | Educational games | CT skills | Hedges’ g | 0.766 | [0.580, 0.951] | <0.001 | 311.834 (0.000) | 87.81% | Y |

| 11 | Xu et al. (2023) | Web of Science Core, ERIC, ScienceDirect | 2000–2021 | 28 | 98 | 4154 | Learning stage, Intervention duration, Learning scaffold, Programming tool, Evaluation tool | Programming teaching | CT skills | SMD | 0.72 | [0.60, 0.83] | <0.001 | NA | 88% | Y |

| 12 | Wang et al. (2024) | Web of Science | 2019–2023 | 17 | 35 | 1665 | Gender, Education level, Scaffolding, Intervention Length | Empirical interventions | CT skills | Cohen’s d | 0.83 | [0.730, 0.890] | <0.001 | 249.236 (0.000) | 88.26% | Y |

| 13 | Zhang et al. (2024b) | Web of Science, ERIC, IEEE, ScienceDirect, Springer Link, Google Scholar | 2006-2023 | 15 | 22 | NA | School level, Gender, Study duration, Subject, UP categories | Unplugged programming activities | CT skills | Hedges’ g | 0.631 | [0.463, 0.799] | <0.001 | NA | 75% | Y |

| 14 | Wang and Xie (2024) | Web of Science, Google Scholar, Science Direct | 2012–2022 | 26 | 33 | 3381 | Grade Level, Study duration, Culture, Learning strategy, Assessment tools | robot-supported learning | CT skills | Hedges’ g | 0.643 | [0.528, 0.757] | <0.001 | 105.082 (0.000) | 69.45% | Y |

| 15 | Zhang et al. (2024a) | IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, CNKI | 2013–2023 | 31 | NA | NA | Educational stages | project-based learning | CT skills | SMD | 0.57 | [0.50, 0.66] | <0.001 | 577.66 (0.000) | 78% | Y |

References

- Alene, Kefyalew Addis, Lucas Hertzog, Beth Gilmour, Archie CA Clements, and Megan B. Murray. 2024. Interventions to prevent post-tuberculosis sequelae: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 70: 102511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, Evan David, and Rachelle Haroldson. 2021. Analysis of Computational Thinking in Children’s Literature for K-6 Students: Literature as a Non-Programming Unplugged Resource. Journal of Educational Computing Research 59: 1487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bati, Kaan. 2022. A systematic literature review regarding computational thinking and programming in early childhood education. Education and Information Technologies 27: 2059–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bers, Marina Umaschi, Amanda Strawhacker, and Amanda Sullivan. 2022. The state of the field of computational thinking in early childhood education. In OECD Education Working Papers. Paris: OECD Publishing, vol. 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocconi, Stefania. 2016. Developing Computational Thinking in Compulsory Education. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, Michael, Larry V. Hedges, Julian P. T. Higgins, and Hannah R. Rothstein. 2009. Effect Sizes Based on Means. In Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Karen, and Mitchel Resnick. 2012. New frameworks for studying and assessing the development of computational thinking. Paper presented at 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Vancouver, BC, Canada, April 13–17, vol. 1, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 2000. Ecological Systems Theory. Washington: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Haiyan, and Gary K. W. Wong. 2024. A systematic review of studies of parental involvement in computational thinking education. Interactive Learning Environments 32: 5373–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo Salamanca, Sandra Liliana, Andy Parra-Martínez, Ammi Chang, Yukiko Maeda, and Anne Traynor. 2024. The Effect of Scoring Rubrics Use on Self-Efficacy and Self-Regulation. Educational Psychology Review 36: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinal, Alejandro, Camilo Vieira, and Alejandra J. Magana. 2024. Professional Development in Computational Thinking: A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Transactions on Computing Education 24: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerlund, Janne, Päivi Häkkinen, Mikko Vesisenaho, and Jouni Viiri. 2021. Computational thinking in programming with Scratch in primary schools: A systematic review. Computer Applications in Engineering Education 29: 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanchamps, Nardie, Emily van Gool, Lou Slangen, and Paul Hennissen. 2024. The effect on computational thinking and identified learning aspects: Comparing unplugged smartGames with SRA-Programming with tangible or On-screen output. Education and Information Technologies 29: 2999–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidai, Aamir, Mary Margaret Capraro, and Robert M. Capraro. 2020. “Scratch”-ing computational thinking with Arduino: A meta-analysis. Thinking Skills and Creativity 38: 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Shuchen, Yuanyuan Zheng, and Xiaoming Zhai. 2024. Artificial intelligence in education research during 2013–2023: A review based on bibliometric analysis. Education and Information Technologies 29: 16387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Núñez, Sandra Erika, Aixchel Cordero-Hidalgo, and Javier Tarango. 2022. Implications of Computational Thinking Knowledge Transfer for Developing Educational Interventions. Contemporary Educational Technology 14: 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Lan. 2024. The impact of educational robots on students’ computational thinking: A meta-analysis of K-12. Education and Information Technologies 29: 13813–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Ting-Chia, and Mu-Sheng Chen. 2025. Effects of students using different learning approaches for learning computational thinking and AI applications. Education and Information Technologies 30: 7549–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Ting-Chia, Shao-Chen Chang, and Yu-Ting Hung. 2018. How to learn and how to teach computational thinking: Suggestions based on a review of the literature. Computers & Education 126: 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Álvarez, Vanessa, and Ana María Pinto-Llorente. 2025. Exploring Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions of the Educational Value and Benefits of Computational Thinking and Programming. Sustainability 17: 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Hao-Yue, and Maria Cutumisu. 2024. Cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal deeper learning domains: A systematic review of computational thinking. Education and Information Technologies 29: 22723–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafai, Yasmin B. 2005. Constructionism. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. Edited by R. K. Sawyer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaki, Kalliopi, Stergios Chatzakis, and Michail Kalogiannakis. 2025. Fostering Algorithmic Thinking and Environmental Awareness via Bee-Bot Activities in Early Childhood Education. Sustainability 17: 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kio, Su Iong. 2016. Extending social networking into the secondary education sector. British Journal of Educational Technology 47: 721–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kite, Vance, Soonhye Park, and Eric Wiebe. 2019. Recognizing and Questioning the CT Education Paradigm. Paper presented at 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, Minneapolis, MN, USA, February 27–March 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiger, Kurt, J. Kevin Ford, and Eduardo Salas. 1993. Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 311–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Chih-Chen, and Huei-Tse Hou. 2025. Game-based collaborative decision-making training: A framework and behavior analysis for a remote collaborative decision-making skill training game using multidimensional scaffolding. Universal Access in the Information Society 24: 867–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, Rainer, and Dave Bartram. 2002. Competency and Individual Performance: Modelling the World of Work. In Organizational Effectiveness. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 227–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Xiaoyan, and Gary Ka-wai Wong. 2022. Collaborative versus individual problem solving in computational thinking through programming: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology 53: 150–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Xiaoyan, Jiachu Ye, and Gary Ka Wai Wong. 2023. Effectiveness of collaboration in developing computational thinking skills: A systematic review of social cognitive factors. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 39: 1418–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sang Joon, Gregory M. Francom, and Jeremiah Nuatomue. 2022. Computer science education and K-12 students’ computational thinking: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research 114: 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Feng, Xi Wang, Xiaona He, Liang Cheng, and Yiyu Wang. 2022. The effectiveness of unplugged activities and programming exercises in computational thinking education: A Meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies 27: 7993–8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xinlei, Guoyuan Sang, Martin Valcke, and Johan van Braak. 2024. Computational thinking integrated into the English language curriculum in primary education: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies 29: 17705–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yeping, Alan H. Schoenfeld, Andrea A. diSessa, Arthur C. Graesser, Lisa C. Benson, Lyn D. English, and Richard A. Duschl. 2020. On Computational Thinking and STEM Education. Journal for STEM Education Research 3: 147–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Yu-Shan, Shih-Yeh Chen, Chia-Wei Tsai, and Ying-Hsun Lai. 2021. Exploring Computational Thinking Skills Training Through Augmented Reality and AIoT Learning. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 640115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Zhuotao, Ming M. Chiu, Yunhuo Cui, Weijie Mao, and Hao Lei. 2022. Effects of Game-Based Learning on Students’ Computational Thinking: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research 61: 235–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins de Souza, Adriano, Fabio Neves Puglieri, and Antonio Carlos de Francisco. 2024. Competitive Advantages of Sustainable Startups: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Directions. Sustainability 16: 7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menolli, André, and João Coelho Neto. 2022. Computational thinking in computer science teacher training courses in Brazil: A survey and a research roadmap. Education and Information Technologies 27: 2099–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Armero, José Miguel, González-Calero José Antonio, and Ramón Cózar-Gutiérrez. 2022. Computational thinking in K-12 education. An insight through meta-analysis. Journal of Research on Technology in Education 54: 410–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleenud, Inthira, Krittika Tanprasert, and Sakulkarn Waleeittipat. 2024. Lecture-Based and Project-Based Approaches to Instruction, Classroom Learning Environment, and Deep Learning. European Journal of Educational Research 13: 531–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papert, Seymour. 1980. Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. New York City: Basic Books, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Passey, Don. 2017. Computer science (CS) in the compulsory education curriculum: Implications for future research. Education and Information Technologies 22: 421–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, Miguel Antonio Soplin, Melany Dayana Cervantes-Marreros, José Dilmer Cubas-Pérez, Luis Alfredo Reategui-Apagueño, David Tito-Pezo, Jhim Max Piña-Rimarachi, Cesar Adolfo Vasquez-Perez, Claudio Leandro Correa-Vasquez, Jose Antonio Soplin Rios, Lisveth Flores del Pino, and et al. 2025. Project-Based Learning at Universities: A Sustainable Approach to Renewable Energy in Latin America—A Case Study. Sustainability 17: 5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Toluchuri Shalini Shanker, and Kaushal Kumar Bhagat. 2024. Computational thinking for the digital age: A systematic review of tools, pedagogical strategies, and assessment practices. Educational Technology Research and Development 72: 1893–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Core Team. [Google Scholar]

- Román-González, Marcos, Juan-Carlos Pérez-González, Jesús Moreno-León, and Gregorio Robles. 2018. Extending the nomological network of computational thinking with non-cognitive factors. Computers in Human Behavior 80: 441–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samdrup, Tshering, James Fogarty, Ram Pandit, Md Sayed Iftekhar, and Kinlay Dorjee. 2023. Does FDI in agriculture in developing countries promote food security? Evidence from meta-regression analysis. Economic Analysis and Policy 80: 1255–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, Beverley J., Barnaby C. Reeves, George Wells, Micere Thuku, Candyce Hamel, Julian Moran, David Moher, Peter Tugwell, Vivian Welch, Elizabeth Kristjansson, and et al. 2017. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 358: j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Dan, Chee-Kit Looi, Yan Li, Chengcong Zhu, Caifeng Zhu, and Miaoting Cheng. 2024. Block-based versus text-based programming: A comparison of learners’ programming behaviors, computational thinking skills and attitudes toward programming. Educational Technology Research and Development 72: 1067–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Lihui, and Liang Zhou. 2023. Does text-based programming improve K-12 students’ CT skills? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Thinking Skills and Creativity 49: 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Lihui, Guo Zhen, and Linlin Hu. 2023. Educational games promote the development of students’ computational thinking: A meta-analytic review. Interactive Learning Environments 31: 3476–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Lihui, Linlin Hu, and Danhua Zhou. 2021. Which way of design programming activities is more effective to promote K-12 students’ computational thinking skills? A meta-analysis. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 37: 1048–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Xiaodan, Yue Yin, Qiao Lin, Roxana Hadad, and Xiaoming Zhai. 2020. Assessing computational thinking: A systematic review of empirical studies. Computers & Education 148: 103798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threekunprapa, Arinchaya, and Pratchayapong Yasri. 2021. The role of augmented reality-based unplugged computer programming approach in the effectiveness of computational thinking. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation 15: 233–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikva, Christina, and Efthimios Tambouris. 2021a. A systematic mapping study on teaching and learning Computational Thinking through programming in higher education. Thinking Skills and Creativity 41: 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikva, Christina, and Efthimios Tambouris. 2021b. Mapping computational thinking through programming in K-12 education: A conceptual model based on a systematic literature Review. Computers & Education 162: 104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakhabova, Selima Aslambekovna, Valery V. Kosulin, and Ana Zizaeva. 2025. Artificial intelligence in education: Challenges and opportunities for sustainable development. Ekonomika i Upravlenie: Problemy, Resheniya 5: 173–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls Pou, Albert, Xavi Canaleta, and David Fonseca. 2022. Computational Thinking and Educational Robotics Integrated into Project-Based Learning. Sensors 22: 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, Wolfgang. 2010. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. Journal of Statistical Software 36: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaowen, Kan Kan Chan, Qianru Li, and Shing On Leung. 2024. Do 3–8 Years Old Children Benefit From Computational Thinking Development? A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research 62: 962–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xinyue, Mengmeng Cheng, and Xinfeng Li. 2023. Teaching and Learning Computational Thinking Through Game-Based Learning: A Systematic Review. Journal of Educational Computing Research 61: 1505–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yang, and Bin Xie. 2024. Can robot-supported learning enhance computational thinking?—A meta-analysis. Thinking Skills and Creativity 52: 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Xiaojing, Huiyan Ye, Yun Dai, and Oi-lam Ng. 2024. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Computational Thinking in Educational Contexts: A Systematic Review of Instructional Design and Student Learning Outcomes. Journal of Educational Computing Research 62: 1420–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, Jeannette M. 2006. Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM 49: 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfart, Olivia, and Ingo Wagner. 2023. Teachers’ role in digitalizing education: An umbrella review. Educational Technology Research and Development 71: 339–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwatkit, Charoenchai, Patcharin Panjaburee, Niwat Srisawasdi, and Pongpon Seprum. 2020. Moderating effects of gender differences on the relationships between perceived learning support, intention to use, and learning performance in a personalized e-learning. Journal of Computers in Education 7: 229–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Ting-Ting, Lusia Maryani Silitonga, and Astrid Tiara Murti. 2024. Enhancing English writing and higher-order thinking skills through computational thinking. Computers & Education 213: 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Enwei, Wei Wang, and Qingxia Wang. 2023. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of programming teaching in promoting K-12 students’ computational thinking. Education and Information Technologies 28: 6619–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Huiyan, Biyao Liang, Oi-Lam Ng, and Ching Sing Chai. 2023. Integration of computational thinking in K-12 mathematics education: A systematic review on CT-based mathematics instruction and student learning. International Journal of STEM Education 10: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeni, Sabiha, Nataša Grgurina, Mara Saeli, Felienne Hermans, Jos Tolboom, and Erik Barendsen. 2024. Interdisciplinary integration of computational thinking in K-12 education: A systematic review. Informatics in Education 23: 223–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Stella Xin, Dion Hoe-Lian Goh, and Choon Lang Quek. 2024. Collaborative Learning in K-12 Computational Thinking Education: A Systematic Review. Journal of Educational Computing Research 62: 1220–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, LeChen, and Jalal Nouri. 2019. A systematic review of learning computational thinking through Scratch in K-9. Computers & Education 141: 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Wuwen, Yurong Guan, and Zhihua Hu. 2024a. The efficacy of project-based learning in enhancing computational thinking among students: A meta-analysis of 31 experiments and quasi-experiments. Education and Information Technologies 29: 14513–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yanjun, Ronghua Luo, Yijin Zhu, and Yuan Yin. 2021. Educational Robots Improve K-12 Students’ Computational Thinking and STEM Attitudes: Systematic Review. Journal of Educational Computing Research 59: 1450–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yanjun, Yanping Liang, Xiaohong Tian, and Xiao Yu. 2024b. The effects of unplugged programming activities on K-9 students’ computational thinking: Meta-analysis. Educational Technology Research and Development 72: 1331–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Ning, Y.; Shi, Y. From Evidence to Insight: An Umbrella Review of Computational Thinking Research Syntheses. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13120157

Zhang J, Wu Y, Ning Y, Shi Y. From Evidence to Insight: An Umbrella Review of Computational Thinking Research Syntheses. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(12):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13120157

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jin, Yaxin Wu, Yimin Ning, and Yafei Shi. 2025. "From Evidence to Insight: An Umbrella Review of Computational Thinking Research Syntheses" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 12: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13120157

APA StyleZhang, J., Wu, Y., Ning, Y., & Shi, Y. (2025). From Evidence to Insight: An Umbrella Review of Computational Thinking Research Syntheses. Journal of Intelligence, 13(12), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13120157