Flexible Regulation of Positive and Negative Emotion Expression: Reexamining the Factor Structure of the Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression Scale (FREE) Based on Emotion Valence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Factor Structure of FREE

1.2. Expression Regulation Abilities for Mental Health and Social Functioning

1.3. Need to Differentiate between Positive and Negative Emotion Expression Abilities

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression (FREE) Scale

2.2.2. Emotion Regulation Self-Efficacy

2.2.3. Symptoms of Depressive, Anxiety, and Stress

2.2.4. College Students Stress

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

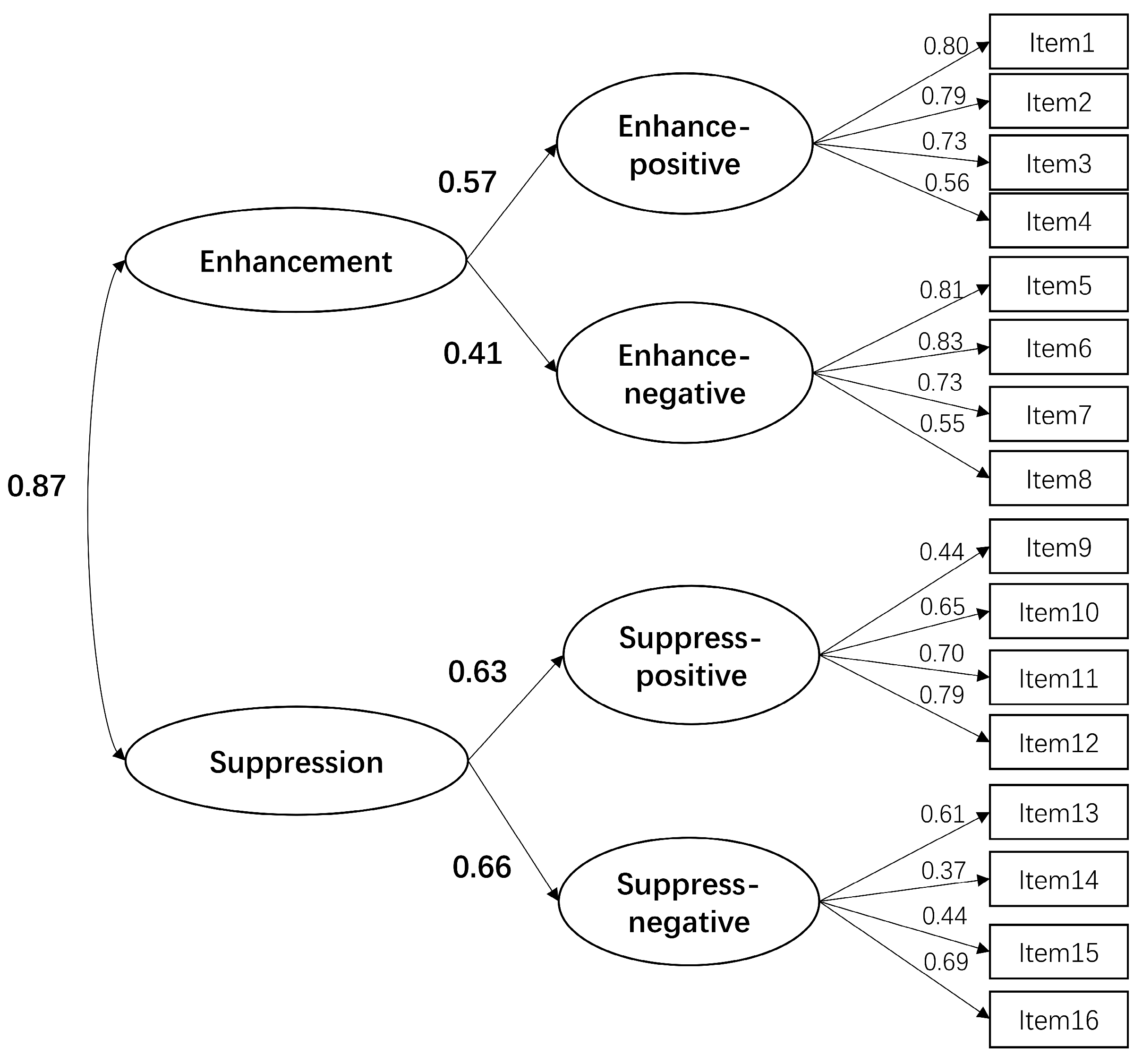

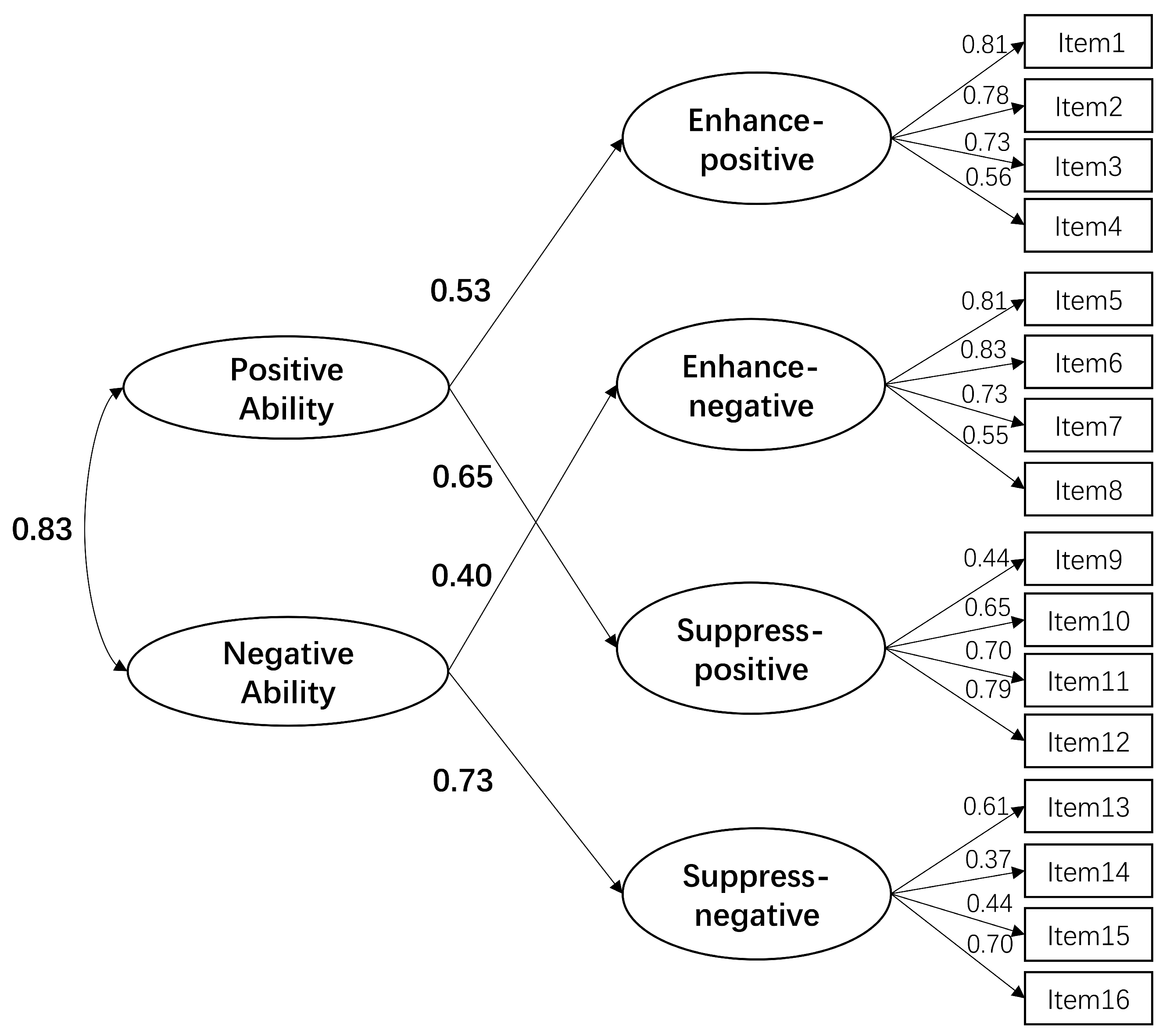

3.2. Factor Analysis

3.3. Internal Consistency and Test–Rest Reliability

3.4. Predictive Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldao, Amelia, and Susan Nolen-Hoeksema. 2012. The influence of context on the implementation of adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy 50: 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldao, Amelia, Gal Sheppes, and James J. Gross. 2015. Emotion Regulation Flexibility. Cognitive Therapy & Research 39: 263–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, Amelia, Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, and Susanne Schweizer. 2010. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review 30: 217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, Jen Yin Zhen, and William Tsai. 2023. Cultural differences in the relations between expressive flexibility and life satisfaction over time. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1204256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, George A., and Charles L. Burton. 2013. Regulatory Flexibility an Individual Differences Perspective on Coping and Emotion Regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science 8: 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, George A., Anthony Papa, Kathleen Lalande, Maren Westphal, and Karin Coifman. 2004. The importance of being flexible: The ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science 15: 482–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, Charles L., and George A. Bonanno. 2016. Measuring Ability to Enhance and Suppress Emotional Expression: The Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression (FREE) Scale. Psychological Assessment 28: 929–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, Gian Vittorio, Laura Di Giunta, Nancy Eisenberg, Maria Gerbino, Concetta Pastorelli, and Carlo Tramontano. 2008. Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychological Assessment 20: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shuquan, and George A. Bonanno. 2021. Components of emotion regulation flexibility: Linking latent profiles to depressive and anxious symptoms. Clinical Psychological Science 9: 236–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shuquan, Kaiwen Bi, Xuerui Han, Pei Sun, and George A. Bonanno. 2024. Emotion regulation flexibility and momentary affect in two cultures. Nature Mental Health 2: 450–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shuquan, Tong Chen, and George A. Bonanno. 2018. Expressive flexibility: Enhancement and suppression abilities differentially predict life satisfaction and psychopathology symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences 126: 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Cecilia, Hi-Po Bobo Lau, and Man-Pui Sally Chan. 2014. Coping flexibility and psychological adjustment to stressful life changes: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin 140: 1582–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, Gordon W., and Roger B. Rensvold. 2002. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling 9: 233–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorley, James D., and Todd B. Kashdan. 2021. Positive and Negative Emotion Regulation in College Athletes: A Preliminary Exploration of Daily Savoring, Acceptance, and Cognitive Reappraisal. Cognitive Therapy and Research 45: 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, Craig K. 2010. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Xu, Xi-yao Xie, Rui Xu, and Yue-jia Luo. 2010. Psychometric properties of the Chinese Versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology 18: 443–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Escamilla, Gabriel, Denise Dörfel, Miriam Becke, Janina Trefz, George A. Bonanno, and Sergiu Groppa. 2022. Associating Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression with Psychopathological Symptoms. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 16: 924305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Sumati, and George A. Bonanno. 2011. Complicated grief and deficits in emotional expressive flexibility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 120: 635–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, Ann-Christin, Christine B. Cha, Jennie G. Noll, Dylan G. Gee, Chad E. Shenk, Hannah M. Schreier, Christine M. Heim, Idan Shalev, Emma J. Rose, Alana Jorgensen, and et al. 2022. The Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression Scale for Youth (FREE-Y): Adaptation and Validation Across a Varied Sample of Children and Adolescents. Assessment 30: 1265–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. Paul, Daniella J. Furman, Catie Chang, Moriah E. Thomason, Emily Dennis, and Ian H. Gotlib. 2011. Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: Implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biological Psychiatry 70: 327–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis. Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, Sinead M., and Ann-Marie Creaven. 2017. Individual differences in positive and negative emotion regulation: Which strategies explain variability in loneliness? Personality and Mental Health 74: 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzo, Vittorio, Maria C. Quattropani, Alberto Sardella, Gabriella Martino, and George A. Bonanno. 2021. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Outbreak and Relationships with Expressive Flexibility and Context Sensitivity. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 623033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Hong, and Jinrong Mei. 2002. Development of the College Student Stress Scale. Applied Psychology 8: 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, Kimberly M., and Sanjay Srivastava. 2012. Up-regulating positive emotions in everyday life: Strategies, individual differences, and associations with positive emotion and well-being. Journal of Research in Personality 46: 504–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccallum, Fiona, Sophia Tran, and George A. Bonanno. 2021. Expressive flexibility and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders 281: 935–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan, and Jannay Morrow. 1993. Effects of rumination and distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cognition and Emotion 7: 561–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Juhyun, and Kristin Naragon-Gainey. 2024. Positive and Negative Emotion-Regulation Ability Profiles: Links with Strategies, Goals, and Internalizing Symptoms. Clinical Psychological Science, onlinefirst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollastri, Alisha R., Jacquelyn Raftery-Helmer, Esteban V. Cardemil, and Michael E. Addis. 2018. Social context, emotional expressivity, and social adjustment in adolescent males. Psychology of Men & Masculinities 19: 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, David A., Rodrigo Becerra, Ken Robinson, Justine Dandy, and Alfred Allan. 2018. Measuring emotion regulation ability across negative and positive emotions: The Perth emotion regulation competency inventory (PERCI). Personality and Individual Differences 135: 229–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattropani, Maria C., V. Lenzo, Alberto Sardella, and George A. Bonanno. 2022. Expressive flexibility and health-related quality of life: The predictive role of enhancement and suppression abilities and relationships with trait emotional intelligence. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 63: 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, Rebecca, George A. Bonanno, Nadia Rahman, Nicole A. Kouri, Richard A. Bryant, Charles R. Marmar, and Adam D. Brown. 2017. Expressive flexibility in combatveterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 207: 236–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Anthony, Steven P. Reise, and Mark G. Haviland. 2016. Applying Bifactor statistical indices in the evaluation of psychological measures. Journal of Personality Assessment 98: 223–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, Prachi, Akanksha Dubey, and Rakesh Pandey. 2011. Role of emotion regulation difficulties in predicting mental health and well-being. Journal of Projective Psychology & Mental Health 18: 147–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shangguan, Chenyu, Lihui Zhang, Yali Wang, Wei Wang, Meixian Shan, and Feng Liu. 2022. Expressive Flexibility and Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Social Support and Gender Differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppes, Gal, Susanne Scheibe, Gaurav Suri, Peter Radu, Jens Blechert, and James J. Gross. 2014. Emotion regulation choice: A conceptual framework and supporting evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General 143: 163–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickland, Megan G., and Alexander J. Skolnick. 2020. Expressive flexibility and trait anxiety in India and the United States. Personality and Individual Differences 163: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, Masayuki, Toshiki Saito, Yutaka Matsuzaki, and Ryuta Kawashima. 2024. Role of positive and negative emotion regulation in well-being and health: The interplay between positive and negative emotion regulation abilities is linked to mental and physical health. Journal of Happiness Studies 25: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kleef, Rozemarijn S., Jan-Bernard C. Marsman, Evelien van Valen, Claudi L. H. Bockting, André Aleman, and Marie José van Tol. 2022. Neural basis of positive and negative emotion regulation in remitted depression. NeuroImage: Clinical 34: 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Yingqian, and Skyler T. Hawk. 2019. Expressive enhancement, suppression, and flexibility in childhood and adolescence: Longitudinal links with peer relations. Emotion 20: 1059–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yingqian, and Skyler T. Hawk. 2020. Development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Flexible Expressiveness (CAFE) Scale. Psychological Assessment 32: 358–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yujie, Kai Dou, and Yi Liu. 2013. Revision of the Scale of Regulatory Emotional Self-efficacy. Journal of Guangzhou University (Social Science Edition) 12: 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, Maren, Nicholas H. Seivert, and George A. Bonanno. 2010. Expressive flexibility. Emotion 10: 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, Katherine S., Christina F. Sandman, and Michelle G. Craske. 2019. Positive and negative emotion regulation in adolescence: Links to anxiety and depression. Brain Sciences 9: 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Shaohua, Junsheng Liu, Biao Sang, and Yuyang Zhao. 2023. Age and gender differences in expressive flexibility and the association with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1185820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yanhua, Kai Wu, Yuanyuan Wang, Guoxiang Zhao, and Entao Zhang. 2022. Construct validity of brief difficulties in emotion regulation scale and its revised version: Evidence for a general factor. Current Psychology 41: 1085–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | α | Gender | Age | Regulatory Self-Efficacy | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Relationship Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhance-positive | 4.57 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 0.09 * | −0.08 | 0.27 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.25 ** |

| Enhance-negative | 3.35 | 1.08 | 0.82 | −0.02 | 0.008 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.09 * | 0.09 * | 0.06 |

| Suppress-positive | 4.18 | 1.03 | 0.73 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.27 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.20 ** |

| Suppress-negative | 3.30 | 0.91 | 0.60 | −0.11 * | 0.03 | 0.22 ** | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.03 |

| Enhancement | 3.96 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.15 ** | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.12 ** |

| Suppression | 3.74 | 0.77 | 0.71 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.31 ** | −0.08 † | −0.09 * | −0.13 ** | −0.15 ** |

| Positive emotion expressive ability | 4.37 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.33 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.28 ** |

| Negative emotion expressive ability | 3.32 | 0.77 | 0.71 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.11 ** | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Flexibility of enhancement and suppression | 7.50 | 1.54 | NA | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.31 ** | −0.08 † | −0.09 * | −0.13 ** | −0.15 ** |

| Flexibility of positive emotion expression | 8.39 | 2.06 | NA | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.27 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.21 ** |

| Flexibility of negative emotion expression | 6.61 | 1.82 | NA | −0.11 * | 0.03 | 0.22 ** | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.03 |

| Total FREE score | 3.85 | 0.64 | 0.78 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.28 ** | −0.08 † | −0.08 † | −0.11 * | −0.16 ** |

| SBχ2 | df | RMSEA (90% CI) | CFI | TLI | SRMR | AIC | BIC | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 2279.36 | 120 | 0.143 (0.136–0.150) | 0.401 | 0.309 | 0.123 | 32,043.493 | 32,255.103 | One-factor CFA |

| M2 | 1008.72 | 103 | 0.120 (0.114–0.127) | 0.581 | 0.511 | 0.115 | 31,632.215 | 31,848.233 | Two-factor CFA for enhance and suppression strategy ability |

| M3 | 760.61 | 103 | 0.103 (0.096–0.109) | 0.695 | 0.645 | 0.107 | 31,338.621 | 31,399.076 | Two-factor CFA for positive and negative ER ability |

| M4 | 189.54 | 98 | 0.039 (0.031–0.048) | 0.958 | 0.948 | 0.050 | 30,658.216 | 30,896.276 | Four-factor CFA for four subscales |

| M5 | 193.63 | 99 | 0.040 (0.031–0.048) | 0.956 | 0.947 | 0.051 | 30,661.468 | 30,895.120 | Second-order four-factor enhance and suppression strategies as higher-order factors |

| M6 | 193.07 | 99 | 0.040 (0.031–0.048) | 0.956 | 0.947 | 0.051 | 30,660.447 | 30,894.099 | Second-order four-factor positive ER ability and negative ER ability as higher-order factors |

| M7 | 234.71 | 100 | 0.047 (0.039–0.055) | 0.951 | 0.941 | 0.051 | 30,660.572 | 30,889.816 | One hierarchical second-order factor |

| M8 | 112.52 | 88 | 0.021 (0.005–0.032) | 0.989 | 0.985 | 0.030 | 30,585.421 | 30,867.567 | Bifactor CFA with one general factor and four specific ER ability |

| DES | Anxiety | Stress | Relationship Stress | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

| Gender | −0.15 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.08 | −0.16 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.06 | −0.13 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.08 | −0.15 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.15 ** |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 * | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 * | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| ER-SEF | −0.31 ** | −0.32 ** | −0.32 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.38 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.36 ** | ||||

| Enhancement | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.09 | −0.26 | −0.26 | ||||||||

| Suppression | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.21 | 0.21 | ||||||||

| EH*SUP | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.03 ** | 0.09 ** | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.02 * | 0.10 ** | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.02 * | 0.12 ** | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 * | 0.13 ** | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Total R2 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Relationship Stress | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

| Gender | −0.15 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.08 | −0.16 ** | −0.14 * | −0.14 * | −0.06 | −0.13 ** | −0.12 * | −0.12 * | −0.08 | −0.15 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.10 * | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.10 * | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| ER−SEF | −0.31 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.32 ** | −0.32 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.38 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.33 ** | ||||

| PA | −0.54 ** | −0.56 ** | −0.43 * | −0.44 * | −0.46 * | −0.47 * | −0.66 ** | −0.66 ** | ||||||||

| NA | 0.56 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.46 * | 0.47 * | 0.46 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.61 * | 0.62 * | ||||||||

| PA*NA | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | ||||||||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.03 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.02 * | 0.001 | 0.02 * | 0.10 ** | 0.02 * | <0.001 | 0.02 * | 0.12 ** | 0.02 * | <0.001 | 0.01 * | 0.13 ** | 0.03 ** | <0.001 |

| Total R2 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Relationship Stress | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | step1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

| Gender | −0.15 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.08 | −0.16 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.06 | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.07 | −0.16 ** | −0.16 ** |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 * | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.10 * | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| ER-SEF | −0.31 ** | −0.31 | −0.33 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.35 | −0.37 ** | −0.36 ** | ||||

| Flexibility | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.04 | ||||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.03 ** | 0.09 ** | <0.001 | 0.02 ** | 0.10 ** | <0.001 | 0.02 * | 0.12 ** | <0.001 | 0.02 * | 0.13 ** | <0.003 |

| Total R2 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Relationship Stress | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

| Gender | −0.15 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.08 † | −0.16 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.06 | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.07 | −0.16 ** | −0.15 ** |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.10 * | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.10 * | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| ER_SEF | −0.31 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.36 ** | ||||

| Flexibility of PE | −0.08 † | −0.07 | −0.08 † | −0.11 * | ||||||||

| Flexibility of NE | 0.09 * | 0.08 † | 0.06 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.03 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.01 † | 0.02 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.01 | 0.02 * | 0.12 ** | 0.01 | 0.02 * | 0.13 ** | 0.01 * |

| Total R2 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Wang, P. Flexible Regulation of Positive and Negative Emotion Expression: Reexamining the Factor Structure of the Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression Scale (FREE) Based on Emotion Valence. J. Intell. 2024, 12, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12090085

Zhao Y, Wang P. Flexible Regulation of Positive and Negative Emotion Expression: Reexamining the Factor Structure of the Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression Scale (FREE) Based on Emotion Valence. Journal of Intelligence. 2024; 12(9):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12090085

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yanhua, and Ping Wang. 2024. "Flexible Regulation of Positive and Negative Emotion Expression: Reexamining the Factor Structure of the Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression Scale (FREE) Based on Emotion Valence" Journal of Intelligence 12, no. 9: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12090085

APA StyleZhao, Y., & Wang, P. (2024). Flexible Regulation of Positive and Negative Emotion Expression: Reexamining the Factor Structure of the Flexible Regulation of Emotional Expression Scale (FREE) Based on Emotion Valence. Journal of Intelligence, 12(9), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12090085