The Purposes of Intellectual Assessment in Early Childhood Education: An Analysis of Chilean Regulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purposes and Multi-Purposes of Assessments in Educational Contexts

1.2. Purposes of Intellectual Assessments in Early Childhood Education

1.3. Educational Inclusion Policy in Chile

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Selection of Normative Documents

2.2. Textual Corpus Obtained

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

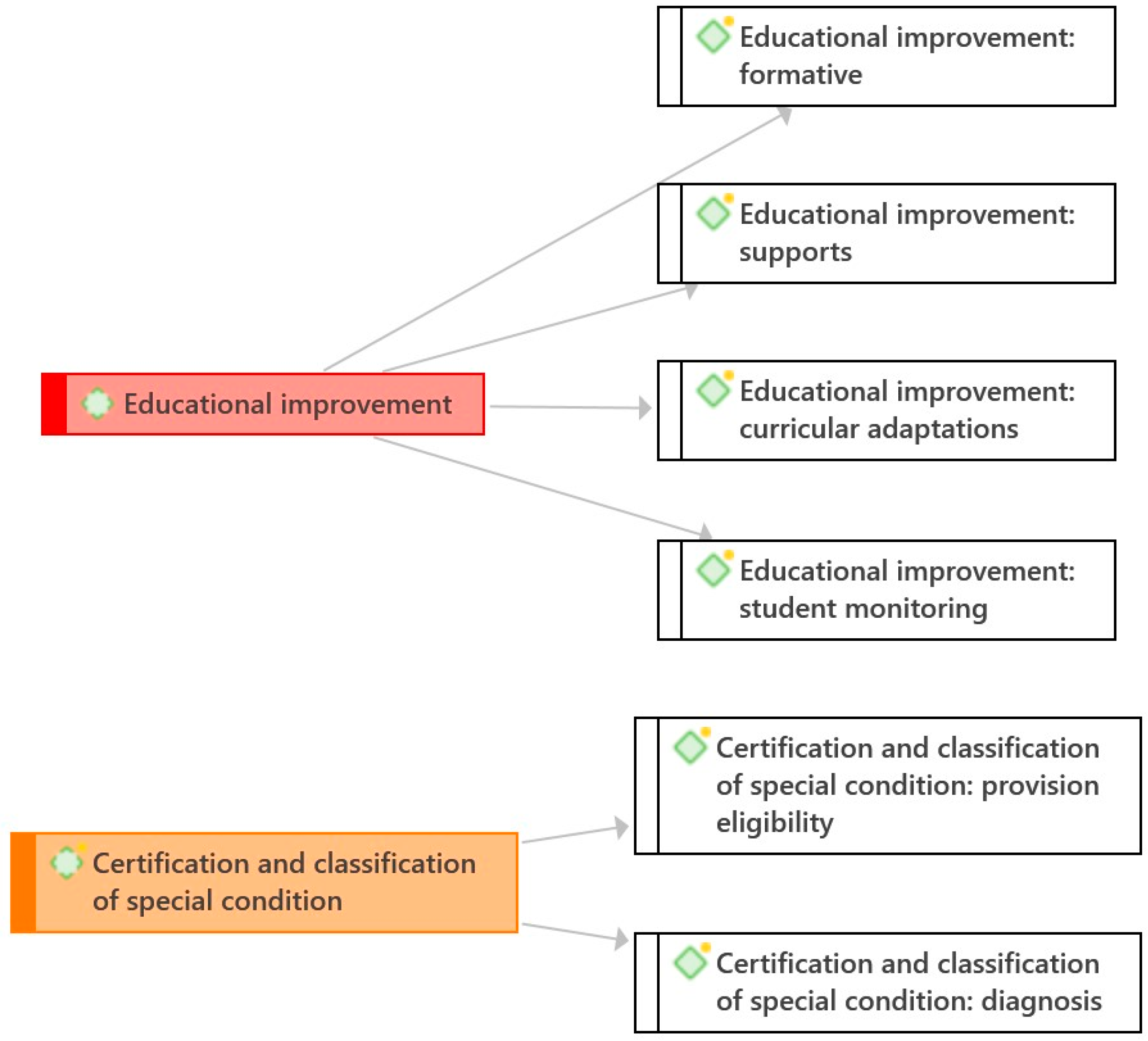

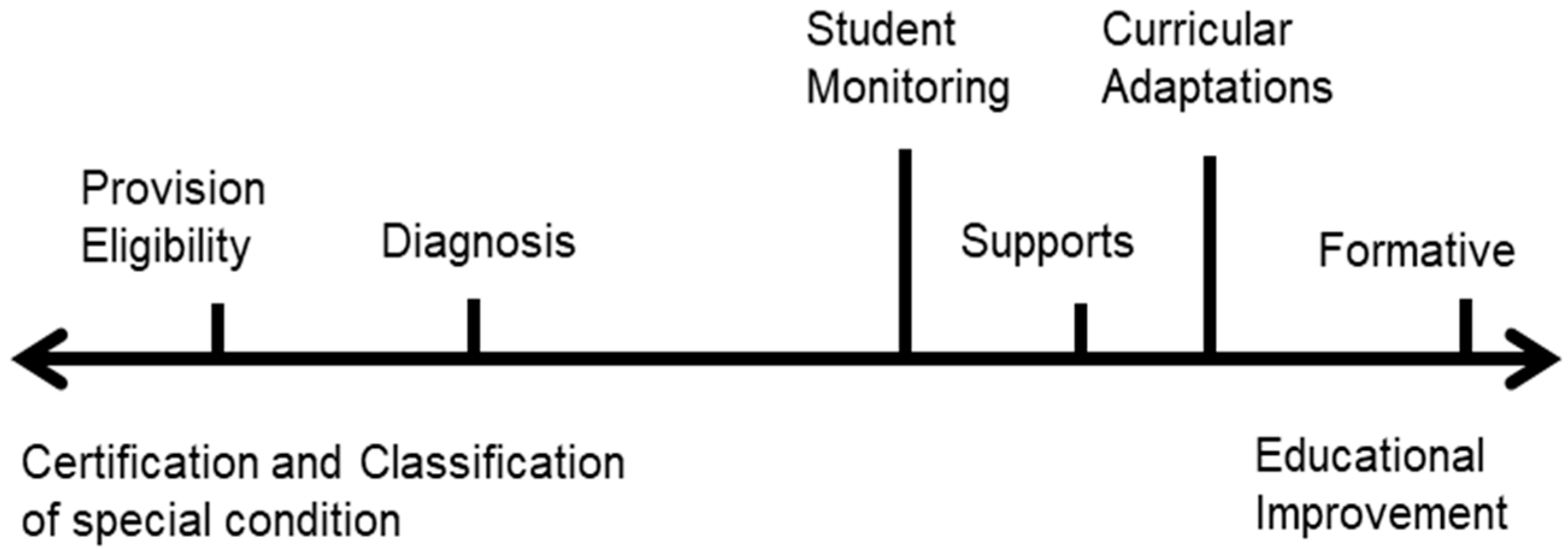

3.1. Assessment Purposes

3.1.1. Assessing to Certify and Classify the Special Condition

In many cases, this role [eligibility] has tended to be visualized and/or assumed in a bureaucratic manner, with the sole purpose of validating, administratively, that the student presents the deficit, disorder or disability condition that will allow him/her to be incorporated into the PIE and receive the special education subsidy.(Document G, p. 16)

Its purpose is to identify, broadly speaking, those SEN that require primary attention due to their impact on the student’s development and learning process, and that also imply extra measures of a temporary or permanent nature.(Document A, p. 46)

The assessment (…) focuses not only on the determination of the student’s difficulties but also on their potential, as well as on the identification of all those factors of the educational and familial context that may influence their educational progress.(Document A, p. 16)

If the diagnostic assessment determines the presence of SEN, the student should be subjected to psychoeducational intervention, for which, if they meet the criteria indicated in the regulations, the establishment can apply to a School Integration Program (PIE). If they do not meet them, other measures must be taken to support their learning process.(Document B, p. 24)

3.1.2. Assessing to Improve Educational Processes

3.2. Consistency of the Purposes Identified with the Current Regulations

3.2.1. Viability of the Identified Purposes in Relation to the Current Regulations

3.2.2. Coincidences between the Document Purposes and Current Regulations

4. Discussion

Study Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Apablaza, Marcela. 2018. Inclusion in education, occupational marginalization and apartheid: An analysis of Chilean education policies. Journal of Occupational Science 25: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspden, Karyn, Stacey M. Baxter, Sally Clendon, and Tara W. McLaughlin. 2022. Identification and referral for early intervention services in New Zealand: A look at teachers’ perspectives—Past and present. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 41: 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnato, Stephen J., Mary McLean, Marisa Macy, and John T. Neisworth. 2011. Identifying instructional targets for early childhood via authentic assessment: Alignment of professional standards and practice-based evidence. Journal of Early Intervention 33: 243–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Eva L. 2013. The chimera of validity. Teachers College Record 115: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Gavin. 2020. Responding to assessment for learning: A pedagogical method, not assessment. New Zealand Annual Review of Education 26: 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Gavin, and John Hattie. 2012. The benefits of regular standardized assessment in childhood education: Guiding improved instruction and learning. In Contemporary Debates in Childhood Education and Development. Edited by Sebastian Suggate and Elaine Reese. New York: Routledge, pp. 287–92. [Google Scholar]

- Brue, Alan. W., and Linda Wilmshurst. 2016. Essentials of Intellectual Disability Assessment and Identification. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Estudios del Ministerio de Educación. 2019. Estadísticas de la educación 2018 [Education Statistics of 2018]. Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, Dante, Miguel Brante, Sebastián Espinoza, and Isabel Zuñiga. 2020. The effect of the integration of students with special educational needs: Evidence from Chile. International Journal of Educational Development 74: 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, Carolina, Eduardo Olivera, Nancy Lepe, and Rubén Vidal. 2017. Perception of educational agents in relation to attention to diversity in educational establishments. Educare 21: 327–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, Marie, Maree Inder, and Richard Porter. 2015. Conducting qualitative research in mental health: Thematic and content analyses. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 49: 616–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decree No. 1. 1998. Reglamenta capitulo II título IV de la ley nº 19.284 que establece normas para la integración social de personas con discapacidad. Diario Oficial. 36.586. January 13. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=120356 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Decree No. 170. 2009. Fija normas para determinar los alumnos con necesidades educativas especiales que serán beneficiarios de las subvenciones para educación especial [Establishes Norms to Determine the Students with Special Dducation Needs That Will Be Beneficiaries of the Subsidies for Special Education]. Diario Oficial. 39.641. May 14. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1012570 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Decree No. 67. 2018. Aprueba normas mínimas nacionales sobre evaluación, calificación y promoción [Establishes Norms about Evaluation, Grading and Promotion]. Diario Oficial. 42.242. February 20. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1127255 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children. 2014. DEC Recommended Practices in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education 2014. Available online: http://www.dec-sped.org/dec-recommended-practices (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Farmer, Ryan L., and Randy Floyd. 2018. Use of intelligence tests in the identification of children and adolescents with intellectual disability. In Contemporary Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues, 4th ed. Edited by Dawn P. Flanagan and Erin M. McDonough. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 643–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Mary, and Luanna H. Meyer. 2002. Development and social competence after two years for students enrolled in inclusive and self-contained educational programs. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 27: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, Dawn P., and Vicente C. Alfonso. 2017. Essentials of WISC-V Assessment. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Flórez, María T., Tamara Rozas, Jacqueline Gysling, and José M. Olave. 2018. The consequences of metrics for social justice: Tensions, pending issues, and questions. Oxford Review of Education 44: 651–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, Randy G., and John H. Kranzler. 2015. The role of intelligence testing in understanding students’ academic problems. In Assessment for Intervention: A Problem-Solving Approach. Edited by Rachel Brown-Chidsey and Kristina J. Andren. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 229–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, Laurie, and V. Susan Dahinten. 2005. Use of intelligence tests in the assessment of preschoolers. In Contemporary Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues, 2nd ed. Edited by Dawn P. Flanagan and Patti L. Harrison. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 487–503. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, Laurie, Michelle L. Kozey, and Juliana Negreiros. 2012. Cognitive assessment in early childhood: Theoretical and practice perspectives. In Contemporary Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues, 3rd ed. Edited by Dawn P. Flanagan and Patti L. Harrison. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 585–622. [Google Scholar]

- García, Rosalba M. C., and Verónica López. 2019. Special education policies in Chile (2005–2015): Continuities and changes. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial 25: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gipps, Caroline V. 1994. Beyond Testing: Towards a Theory of Educational Assessment. London: The Falmer Press, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gysling, Jacqueline. 2016. The historical development of educational assessment in Chile: 1810–2014. Assessment in Education 23: 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Andrew D. 2014. Variety and drift in the functions and purposes of assessment in K–12 education. Teachers College Record 116: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenni, Oskar G., Sylvia Fintelmann, Jon Caflisch, Beatrice Latal, Valentin Rousson, and Aziz Chaouch. 2015. Stability of cognitive performance in children with mild intellectual disability. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 57: 463–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, Anders. 2020. Definitions of formative assessment need to make a distinction between a psychometric understanding of assessment and “evaluative judgment”. Frontiers in Education 5: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaya, Tomoe. 2019. Intelligence and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Journal of Intelligence 7: 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Alan S., Susan Engi Raiford, and Diane L. Coalson. 2016. Intelligent Testing with the WISC-V. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Martha J. 2013. The Multiple-use of accountability assessments: Implications for the process of validation. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 32: 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzler, John H. 1997. Educational and policy issues related to the use and interpretation of Intelligence tests in the schools. School Psychology Review 26: 150–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, Carmen, and Simon Whitaker. 2011. The use of IQ and descriptions of people with intellectual disabilities in the scientific literature. The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities 57: 175–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, Alysee, Annie Davis, Gracelyn Cruden, Christina Padilla, and Yonah Drazen. 2022. Early childhood suspension and expulsion: A content analysis of state legislation. Early Childhood Education Journal 50: 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Verónica, Pablo González, Dominique Manghi, Paula Ascorra, Juan C. Oyanedel, Silvia Redón, Francisco Leal, and Mauricio Salgado. 2018. Policies of educational inclusion in Chile: Three critical nodes. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas 26: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jiménez, Tatiana, Catalina Castillo, Javiera Taruman, and Allison Urzúa. 2021. Inclusive learning practices: A multiple case study in early childhood education. Revista Educación 45: 102–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, Marisa, Kevin Marks, and Alexander Towle. 2014. Miseed, misused, or mismanaged: Improving early detection system to optimize child outcomes. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 34: 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manghi, Dominique, María L. Conejeros, Andrea Bustos, Isabel Aranda, Vanessa Vega, and Kathiuska Díaz. 2020. Understanding inclusive education in Chile: An overview of policy and educational research. Cuadernos de Pesquisa 50: 114–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrew, Kevin S. 2015. Intellectual functioning. In The Death Penalty and Intellectual Disability. Edited by Edward A. Polloway. Silver Spring: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, pp. 85–111. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2018. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. 2011. Orientaciones para dar respuestas educativas a la diversidad y a las necesidades educativas especiales [Guidelines for Educational Responses to Diversity and Special Educational Needs]; Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. 2013. Orientaciones técnicas para programas de integración escolar (PIE) [Technical Guidelines for School Integration Programs (PIE)]; Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. 2015. Criterios y orientaciones de adecuación curricular para estudiantes con necesidades educativas especiales de educación parvularia y educación básica [Criteria and Guidelines for Curricular Accommodations for Students with Special Educational Needs in Early Childhood and Elementary Education]; Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. 2016. Programa de Integración Escolar PIE. Ley de Inclusión 20.845 [Program of School Integration PIE. Inclusion Law 20.845]; Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. 2017. Orientaciones sobre estrategias diversificadas de enseñanza para educación básica en el marco del decreto 83/2015 [Guidelines on Diversified Instruction Strategies for Elementary Education in the Framework of Decree 83/2015]; Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. 2018a. Bases Curriculares. Educación Parvularia [Curricular Foundations. Early Childhood Education]; Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. 2018b. Documento orientador para el desarrollo de prácticas inclusivas en educación parvularia. Ministerio de Educación [Guidance Document for the Development of Inclusive Practices in Early Childhood Education]; Santiago de Chile: Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia.

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. 2019. Profesionales asistentes de la educación: Orientaciones acerca de su rol y funciones en programas de integración escolar [Guidance on the Role and Functions of Education Assistant Professionals Who Participate in School Integration Programs]; Santiago de Chile: MINEDUC.

- Moreno, Antonio, and Mónica Peña. 2020. The good patient: An analysis of the relationship between children and professionals of the PIE school integration program. Estudios Pedagógicos 46: 267–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, Richard J., Sandra Glover Gagnon, and Pamela Kidder-Ashley. 2020. Issues in preschool assessment. In Psychoeducational Assessment of Preschool Children, 5th ed. Edited by Vicente C. Alfonso, Bruce A. Bracken and Richard J. Nagle. New York: Routledge, pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of School Psychologists. 2015. Early Childhood Services: Promoting Positive Outcomes for Young Children. Available online: https://n9.cl/3pbql (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Newton, Paul E. 2007. Clarifying the purposes of educational assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy y Practice 14: 149–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, Paul E. 2010. The multiple purposes of assessment. In International Encyclopedia of Education. Edited by Penelope L. Peterson, Eva Baker and Barry McGaw. New York: Elsevier, pp. 392–96. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Paul E. 2017. There is more to educational measurement than measuring: The importance of embracing purpose pluralism. Educational Measurement 36: 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, Carmen G., Mónica Peña, Bryan González, and Paula Ascorra. 2020. A view from the inclusion to the scholar integration program in chilean rural schools: An analysis of cases. Revista Colombiana de Educación 79: 347–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Cecil R., Robert A. Altmann, and Daniel N. Allen. 2021. Mastering Modern Psychological Testing: Theory and Methods, 2nd ed. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salend, Spencer J., and Laurel M. Garrick. 1999. The impact of inclusion on students with and without disabilities and their Educators. Remedial and Special Education 20: 114–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Vidal, Paulina I., Sergio Gatica-Ferrero, and Lidia Valdenegro-Fuentes. 2020. Evidence of overdiagnosis in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on neuropsychological evaluation: A study in Chilean students. Psicogente 23: 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalock, Robert L., Ruth Luckasson, and Marc J. Tassé. 2021. Intellectual Disability: Definition, Diagnosis, Classification, and Systems of Supports, 12th ed. Spring: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeiser, Cynthia B., and Catherine J. Welch. 2006. Test development. In Educational Measurement, 4th ed. Edited by Robert L. Brennan. Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 309–53. [Google Scholar]

- Snider, Laurel A., Devadrita Talapatra, Gloria Miller, and Duan Zhang. 2020. Expanding best practices in assessment for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Contemporary School Psychology 24: 429–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Patricia A., Corinne S. Wixson, Devadrita Talapatra, and Andrew Roach. 2008. Assessment in early childhood: Instruction-focused strategies to support response-to-intervention frameworks. Assessment for Effective Intervention 34: 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefel, Leanna, Michael Gottfried, Menbere Shiferaw, and Amy Schwartz. 2020. Is special education improving? Case evidence from New York City. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 32: 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobart, Gordon. 2008. Testing Times: The Uses and Abuses of Assessment. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina, Carolina, Pablo Basualto, Camila Durán, and Pablo Miranda. 2017. Co-teaching practices: The case of a teachers’ duo in the school integration program in Chile. Estudios Pedagógicos 63: 355–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwick, Rebecca. 2021. A century of testing controversies. In The History of Educational Measurement. Edited by Brian E. Clauser and Michael B. Bunch. London: Routledge, pp. 136–54. [Google Scholar]

| Alphabetical Identifier | Document Name | Target Level |

|---|---|---|

| A | Guidelines for educational responses to diversity and special educational needs (Ministerio de Educación MINEDUC 2011) | Early childhood education |

| B | Technical guidelines for school integration programs (MINEDUC 2013) | All educational levels |

| C | Criteria and guidelines for curricular adaptation for students with special educational needs in early childhood education and elementary education (MINEDUC 2015) | All educational levels |

| D | Guidelines on diversified instruction strategies for elementary education in the framework of decree 83/2015 (MINEDUC 2017) | Early childhood education |

| E | Support manual for the implementation of PIE (MINEDUC 2016) | All educational levels |

| F | Guidance document for the development of inclusive practices in early childhood education (MINEDUC 2018b) | Early childhood education |

| G | Guidance on the role and functions of education assistant professionals who participate in school integration programs (PIE) (MINEDUC 2019) | All educational levels |

| Term | Definition | Codification Rules |

|---|---|---|

| Student Monitoring | Determine whether students are progressing adequately over time against specific learning or intervention objectives. | Rule 1. This applies when the purpose is to determine the adequacy of supports and interventions while they are being provided. Rule 2. Does not imply an improvement in the classroom teacher’s instruction. |

| Learning Certifications | Indicate whether students have met the requirements (knowledge, skills, etc.) of a given course. | This applies when it is intended to indicate whether students have met the requirements associated with the knowledge, objectives, and skills of the level. |

| Formative | Identify student learning gaps or needs to guide and improve subsequent instruction and learning. | Rule 1. This applies when the classroom teacher decides to modify and improve their instruction for all the students in the class. Rule 2. This does not apply when the decision is made by the special education teacher. |

| Screening | Identify students who differ significantly from their peers in certain areas or dimensions to deepen assessment. | This applies when the decision involves referring the child for any kind of further evaluation. |

| Diagnosis | Clarify the type and extent of the student’s learning difficulties in light of specific criteria. | This applies when the decision is to establish a category, label, typology, or description that communicates the student’s learning difficulties or the extent (degree) of the difficulty. |

| Provision Eligibility | Determine whether the student meets the criteria for accessing special education services and aids. | Rule 1. This applies when the decision is whether to enter the School Integration Program (PIE) or not. Rule 2. This applies also when the decision is the discharge from the PIE program. |

| Placement | Placing students at particular instructional levels or in particular educational programs that are more educationally enriching for them. | This applies when the decision is to place students in certain educational levels or curricular acceleration programs. |

| Segregation | Segregate students into homogeneous groups based on ability or achievement to make instruction simpler or more viable. | This applies when the decision is to group students within the classroom or in special classrooms according to their aptitudes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ancapichún, A.; López-Jiménez, T. The Purposes of Intellectual Assessment in Early Childhood Education: An Analysis of Chilean Regulations. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11070134

Ancapichún A, López-Jiménez T. The Purposes of Intellectual Assessment in Early Childhood Education: An Analysis of Chilean Regulations. Journal of Intelligence. 2023; 11(7):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11070134

Chicago/Turabian StyleAncapichún, Alejandro, and Tatiana López-Jiménez. 2023. "The Purposes of Intellectual Assessment in Early Childhood Education: An Analysis of Chilean Regulations" Journal of Intelligence 11, no. 7: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11070134

APA StyleAncapichún, A., & López-Jiménez, T. (2023). The Purposes of Intellectual Assessment in Early Childhood Education: An Analysis of Chilean Regulations. Journal of Intelligence, 11(7), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11070134