Less-Intelligent and Unaware? Accuracy and Dunning–Kruger Effects for Self-Estimates of Different Aspects of Intelligence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Correlational Accuracy of Self-Estimates of Intelligence

1.2. Above-Average Effects and the Miscalibration of Self-Estimates of Intelligence

1.3. Dunning–Kruger Effects

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials and Methods

2.2.1. Intelligence

2.2.2. Self-Estimated Intelligence

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

3.2. Linear Associations between Self-Estimated and Measured Intelligence

3.3. Above-Average Effects and Miscalibration

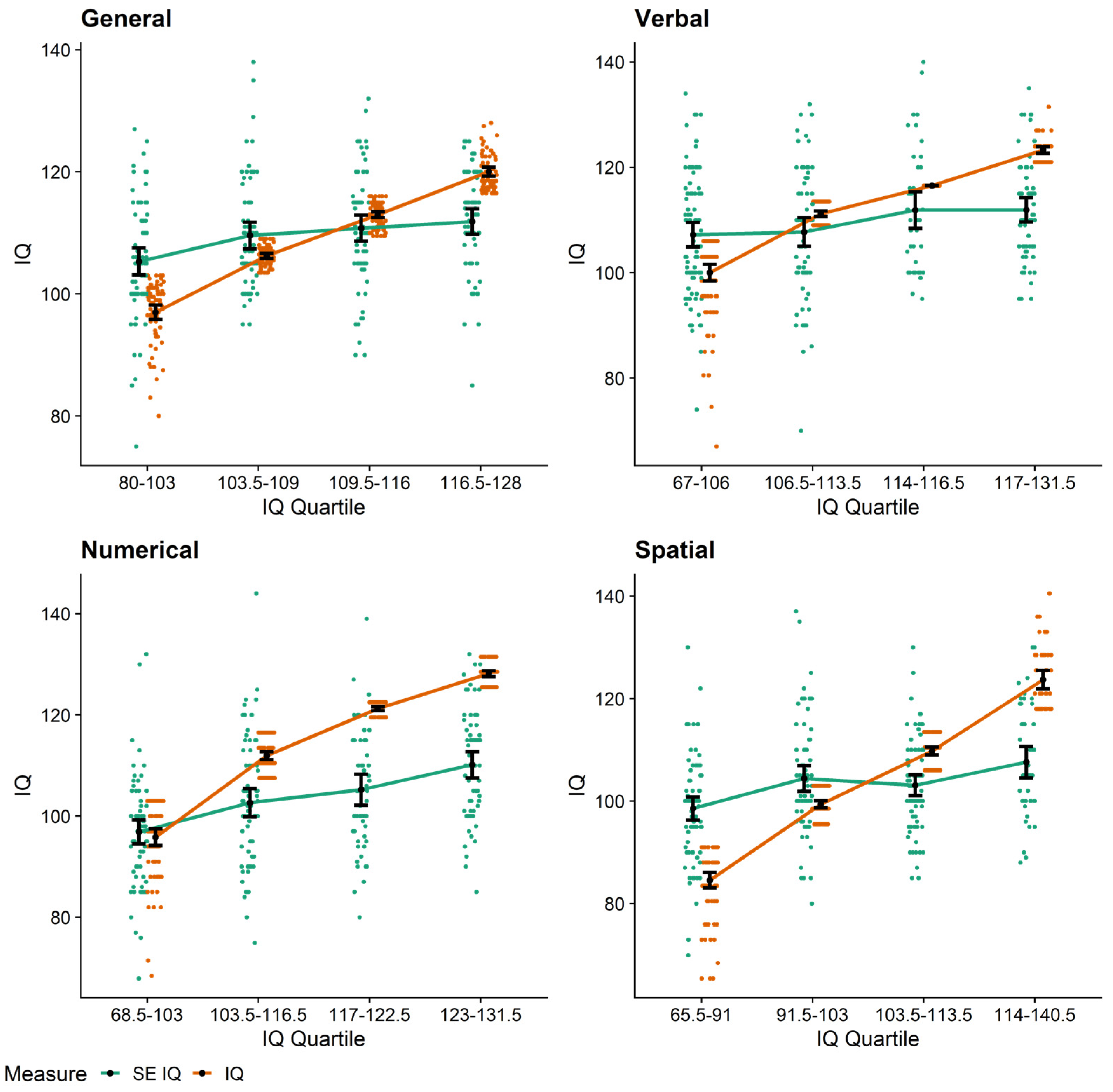

3.4. Dunning–Kruger Effects

3.4.1. Conventional Statistical Approach

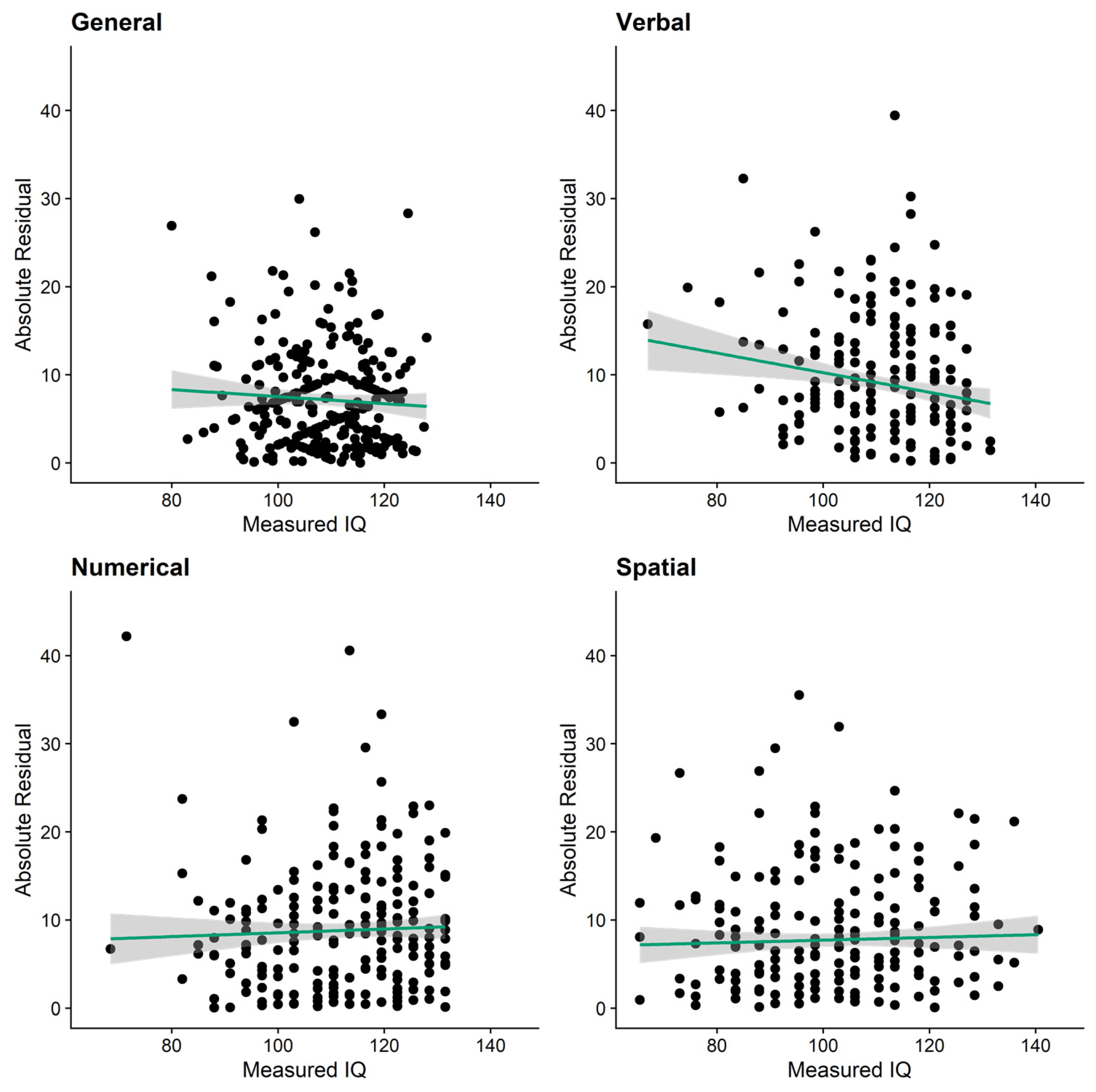

3.4.2. Heteroscedasticity

3.4.3. Nonlinear Regression

3.5. Exploratory Research Question

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Unfortunately, we had overlooked this discrepancy at the planning stage. However, we believe that the self-estimates of the remaining participants are still valid as they were either within the bounds of the intelligence tests or would have also corresponded to an over-/underestimation with intelligence tests with a broader range (e.g., a self-estimated IQ of 138 compared to a measured one of 104). |

References

- Ackerman, Phillip L., and Stacey D. Wolman. 2007. Determinants and validity of self-estimates of abilities and self-concept measures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 13: 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, Phillip L., Margaret E. Beier, and Kristy R. Bowen. 2002. What we really know about our abilities and our knowledge. Personality and Individual Differences 33: 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicke, Mark D., and Olesya Govorun. 2005. The better-than-average effect. In The Self in Social Judgment. Edited by Mark D. Alicke, David Dunning and Joachim I. Krueger. Hove: Psychology Press, pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Burson, Katherine A., Richard P. Larrick, and Joshua Klayman. 2006. Skilled or unskilled, but still unaware of it: How perceptions of difficulty drive miscalibration in relative comparisons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90: 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Campbell, Donald T., and David A. Kenny. 1999. A Primer on Regression Artifacts, 1st ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, Raymond B. 1963. Theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence: A critical experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology 54: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1992. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin 112: 155–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devega, Chauncey. 2020. Our Dunning-Kruger President: Trump’s Arrogance and Ignorance are Killing People. Salon. April 2. Available online: https://www.salon.com/2020/04/02/our-dunning-kruger-president-trumps-arrogance-and-ignorance-are-killing-people/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Diedenhofen, Birk, and Jochen Musch. 2015. cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS ONE 10: e0121945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dufner, Michael, Jochen E. Gebauer, Constantine Sedikides, and Jaap J.A. Denissen. 2018. Self-enhancement and psychological adjustment: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review 23: 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, David. 2011. The Dunning–Kruger effect: On being ignorant of one’s own ignorance. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Edited by James M. Olson and Mark P. Zanna. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 44, pp. 247–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, David, and Geoffrey L. Cohen. 1992. Egocentric definitions of traits and abilities in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63: 341–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, David, and Erik G. Helzer. 2014. Beyond the correlation coefficient in studies of self-assessment accuracy: Commentary on Zell & Krizan. Perspectives on Psychological Science 9: 126–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, David, and Rory O’Brien McElwee. 1995. Idiosyncratic trait definitions: Implications for self-description and social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68: 936–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlinger, Joyce, Kerri Johnson, Matthew Banner, David Dunning, and Justin Kruger. 2008. Why the unskilled are unaware: Further explorations of (absent) self-insight among the incompetent. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 105: 98–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, Seymour. 1983. Aggregation and beyond: Some basic issues on the prediction of behavior. Journal of Personality 51: 360–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fay, Ernst, Günter Trost, and Georg Gittler. 2001. Intelligenz-Struktur-Analyse (ISA). Netherlands: Swets Test Services. [Google Scholar]

- Feld, Jan, Jan Sauermann, and Andries de Grip. 2017. Estimating the relationship between skill and overconfidence. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 68: 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freund, Philipp Alexander, and Nadine Kasten. 2012. How smart do you think you are? A meta-analysis on the validity of self-estimates of cognitive ability. Psychological Bulletin 138: 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Furnham, Adrian. 2001. Self-estimates of intelligence: Culture and gender difference in self and other estimates of both general (g) and multiple intelligences. Personality and Individual Differences 31: 1381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Howard. E. 1999. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gignac, Gilles. E. 2019. How2statsbook, 1st ed. Available online: http://www.how2statsbook.com/p/chapters.html (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Gignac, Gilles E. 2022. The association between objective and subjective financial literacy: Failure to observe the Dunning-Kruger effect. Personality and Individual Differences 184: 111224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, Gilles E., and Eva T. Szodorai. 2016. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences 102: 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, Gilles E., and Marcin Zajenkowski. 2019. People tend to overestimate their romantic partner’s intelligence even more than their own. Intelligence 73: 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, Gilles E., and Marcin Zajenkowski. 2020. The Dunning-Kruger effect is (mostly) a statistical artefact: Valid approaches to testing the hypothesis with individual differences data. Intelligence 80: 101449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glejser, Herbert. 1969. A new test for heteroskedasticity. Journal of the American Statistical Association 64: 316–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Joyce C., and Stéphane Côté. 2019. Self-insight into emotional and cognitive abilities is not related to higher adjustment. Nature Human Behaviour 3: 867–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, Patrick R., Daniel J. Simons, and Christopher F. Chabris. 2018. 65% of Americans believe they are above average in intelligence: Results of two nationally representative surveys. PLoS ONE 13: e0200103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herreen, Danielle, and Ian Zajac. 2018. The reliability and validity of a self-report measure of cognitive abilities in older adults: More personality than cognitive function. Journal of Intelligence 6: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofer, Gabriela, Laura Langmann, Roman Burkart, and Aljoscha C. Neubauer. 2021. Who knows what we are good at? Unique insights of the self, knowledgeable informants, and strangers into a person’s abilities. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, Gabriela, Silvia Macher, and Aljoscha C. Neubauer. 2022. Love is not blind: What romantic partners know about our abilities compared to ourselves, our close friends, and our acquaintances. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, Heinz, and Franzis Preckel. 2005. Self-estimates of intelligence––methodological approaches and gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences 38: 503–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrey, William J., Mary F. Lesch, Eve Mitsopoulos-Rubens, and John D. Lee. 2015. Calibration of skill and judgment in driving: Development of a conceptual framework and the implications for road safety. Accident Analysis & Prevention 76: 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Humberg, Sarah, Michael Dufner, Felix D. Schönbrodt, Katharina Geukes, Roos Hutteman, Albrecht C. P. Küfner, Maarten H. W. Van Zalk, Jaap J. A. Denissen, Steffen Nestler, and Mitja D. Back. 2019. Is accurate, positive, or inflated self-perception most advantageous for psychological adjustment? A competitive test of key hypotheses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 116: 835–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, Adolf O. 1984. Intelligenzstrukturforschung: Konkurrierende Modelle, neue Entwicklungen, Perspektiven. (Structural research on intelligence: Competing models, new developments, perspectives). Psychologische Rundschau 35: 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Rachel A., Anna N. Rafferty, and Thomas L. Griffiths. 2021. A rational model of the Dunning–Kruger effect supports insensitivity to evidence in low performers. Nature Human Behaviour 5: 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, Oliver P., and Richard W. Robins. 1993. Determinants of interjudge agreement on personality traits: The Big Five domains, observability, evaluativeness, and the unique perspective of the self. Journal of Personality 61: 521–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, Young-Hoon, and Chi-Yue Chiu. 2011. Emotional costs of inaccurate self-assessments: Both self-effacement and self-enhancement can lead to dejection. Emotion 11: 1096–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, Young-Hoon, Chi-yue Chiu, and Zhimin Zou. 2010. Know thyself: Misperceptions of actual performance undermine achievement motivation, future performance, and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 99: 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koo, Terry K., and Mae Y. Li. 2016. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 15: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krajč, Marian, and Andreas Ortmann. 2008. Are the unskilled really that unaware? An alternative explanation. Journal of Economic Psychology 29: 724–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krueger, Joachim, and Ross A. Mueller. 2002. Unskilled, unaware, or both? The better-than-average heuristic and statistical regression predict errors in estimates of own performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 180–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, Justin, and David Dunning. 1999. Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 1121–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, Aljoscha C., Anna Pribil, Alexandra Wallner, and Gabriela Hofer. 2018. The self–other knowledge asymmetry in cognitive intelligence, emotional intelligence, and creativity. Heliyon 4: e01061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neubauer, Aljoscha C., and Gabriela Hofer. 2020. Self- and other-estimates of intelligence. In The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence, 2nd ed. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, Aljoscha C., and Gabriela Hofer. 2021. Self-estimates of abilities are a better reflection of individuals’ personality traits than of their abilities and are also strong predictors of professional interests. Personality and Individual Differences 169: 109850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhfer, Edward, Christopher Cogan, Steven Fleisher, Eric Gaze, and Karl Wirth. 2016. Random number simulations reveal how random noise affects the measurements and graphical portrayals of self-assessed competency. Numeracy 9: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pietschnig, Jakob, and Martin Voracek. 2015. One century of global IQ gains: A formal meta-analysis of the Flynn effect (1909–2013). Perspectives on Psychological Science 10: 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressler, Jessica. 2017. Donald Trump, the Dunning-Kruger President. The Cut. January 9. Available online: https://www.thecut.com/2017/01/why-donald-trump-will-be-the-dunning-kruger-president.html (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Schraw, Gregory. 2009. A conceptual analysis of five measures of metacognitive monitoring. Metacognition and Learning 4: 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, Marshall. 2020. 5 Climate Skepticism Tactics Emerging with Coronavirus. Forbes. March 10. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/marshallshepherd/2020/03/10/5-climate-skepticism-tactics-emerging-with-coronavirus/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Simmons, Joseph P., Leif D. Nelson, and Uri Simonsohn. A 21 Word Solution. SSRN. October 14. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2160588 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Steiger, James H. 1980. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin 87: 245–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurstone, Louis L. 1938. Primary Mental Abilities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trahan, Lisa, Karla K. Stuebing, Merril K. Hiscock, and Jack M. Fletcher. 2014. The Flynn Effect: A Meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 140: 1332–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vazire, Simine. 2010. Who knows what about a person? The self–other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98: 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Visser, Beth A., Michael C. Ashton, and Philip A. Vernon. 2008. What makes you think you’re so smart? Measured abilities, personality, and sex differences in relation to self-estimates of multiple intelligences. Journal of Individual Differences 29: 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stumm, Sophie. 2014. Intelligence, gender, and assessment method affect the accuracy of self-estimated intelligence. British Journal of Psychology 105: 243–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Keon, and Asia A. Eaton. 2019. Prejudiced and unaware of it: Evidence for the Dunning-Kruger model in the domains of racism and sexism. Personality and Individual Differences 146: 111–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Evan J. 1959. The comparison of regression variables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 21: 396–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zell, Ethan, and Zlatan Krizan. 2014. Do people have insight into their abilities? A metasynthesis. Perspectives on Psychological Science 9: 111–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Min-Max | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | General IQ | 80.00–128.00 | 108.78 (9.06) | ||||||||||

| 2. | Verbal IQ | 67.00–131.50 | 110.96 (10.27) | .57 | |||||||||

| 3. | Numerical IQ | 68.50–131.50 | 113.28 (13.10) | .77 | .22 | ||||||||

| 4. | Spatial IQ | 65.50–140.50 | 102.11 (14.46) | .78 | .16 | .38 | |||||||

| 5. | SE General IQ | 75.00–138.00 | 109.29 (9.40) | .25 | .18 | .24 | .11 | ||||||

| 6. | SE Verbal IQ | 70.00–140.00 | 109.15 (11.28) | .09 | .10 | .12 | −.02 | .64 | |||||

| 7. | SE Numerical IQ | 68.00–144.00 | 103.35 (12.24) | .40 | .19 | .40 | .26 | .63 | .18 | ||||

| 8. | SE Spatial IQ | 70.00–137.00 | 102.90 (10.58) | .32 | .20 | .18 | .29 | .55 | .17 | .54 | |||

| 9. | SE Verbal Multi-Item | 1.70–4.90 | 3.49 (.61) | .14 | .18 | .15 | −.01 | .40 | .65 | .11 | .08 | ||

| 10. | SE Numerical Multi-Item | 1.00–5.00 | 3.03 (.98) | .40 | .16 | .40 | .28 | .34 | −.09 | .76 | .39 | .12 | |

| 11. | SE Spatial Multi-Item | 1.22–5.00 | 3.16 (.80) | .15 | .11 | .01 | .20 | .19 | −.07 | .21 | .66 | .14 | .38 |

| Domain | SE (IQ) | SE (Multi-Item) | SE (Last Item) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General | .25 | ||

| [.12, .38] | |||

| p < .001 | |||

| Verbal | .10 | .19 | .17 |

| [−.02, .23] | [.08, .28] | [.05, .28] | |

| p = .100 | p < .001 | p = .001 | |

| Numerical | .40 | .40 | .34 |

| [.27, .49] | [.28, .49] | [.21, .44] | |

| p = .003 | p = .001 | p = .002 | |

| Spatial | .29 | .20 | .30 |

| [.18, .40] | [.08, .32] | [.18, .40] | |

| p = .001 | p = .001 | p = .001 |

| Domain | Effect | F | df1 | df2 | p | η2g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Quartile | 116.69 | 3 | 277 | <.001 | .391 |

| Measure | 0.78 | 1 | 277 | .378 | .001 | |

| Quartile × Measure | 37.86 | 3 | 277 | <.001 | .168 | |

| Verbal | Quartile | 84.46 | 3 | 277 | <.001 | .296 |

| Measure | 5.78 | 1 | 277 | .017 | .011 | |

| Quartile × Measure | 30.21 | 3 | 277 | <.001 | .150 | |

| Numerical | Quartile | 174.02 | 3 | 277 | <.001 | .501 |

| Measure | 200.55 | 1 | 277 | <.001 | .253 | |

| Quartile × Measure | 38.72 | 3 | 277 | <.001 | .164 | |

| Spatial | Quartile | 178.22 | 3 | 277 | <.001 | .516 |

| Measure | 1.54 | 1 | 277 | .216 | .002 | |

| Quartile × Measure | 96.01 | 3 | 277 | <.001 | .318 |

| Domain | Quartile | t | df | Mdiff | 95% BCa CI | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | 80–103 | 6.78 | 72 | 8.32 | [5.95; 10.68] | <.001 * | 0.79 |

| 103.5–109 | 2.93 | 68 | 3.33 | [1.20; 5.65] | <.001 * | 0.35 | |

| 109.5–116 | −2.01 | 73 | −2.20 | [−4.39; 0.03] | .055 | −0.23 | |

| 116.5–128 | −7.46 | 64 | −8.18 | [−10.38; −6.12] | <.001 * | −0.92 | |

| Verbal | 67–106 | 4.76 | 96 | 7.20 | [4.36; 10.09] | <.001 * | 0.48 |

| 106.5–113.5 | −2.45 | 74 | −3.44 | [−6.09; −0.86] | .012 * | −0.28 | |

| 114–116.5 | −2.68 | 42 | −4.64 | [−7.92; −1.08] | .018 | −0.41 | |

| 117–131.5 | −9.22 | 65 | −11.36 | [−13.71; −8.86] | <.001 * | −1.13 | |

| Numerical | 68.5–103 | 0.74 | 77 | 1.05 | [−1.58; 3.96] | .442 | 0.08 |

| 103.5–116.5 | −6.90 | 76 | −9.31 | [−11.97; −6.64] | <.001 * | −0.79 | |

| 117–122.5 | −10.13 | 58 | −16.04 | [−19.13; −12.91] | <.001 * | −1.32 | |

| 123–131.5 | −14.41 | 66 | −18.02 | [−20.26; −15.60] | <.001 * | −1.76 | |

| Spatial | 65.5–91 | 11.26 | 79 | 13.98 | [11.67; 16.36] | <.001 * | 1.26 |

| 91.5–103 | 3.91 | 75 | 5.03 | [2.54; 7.56] | <.001 * | 0.45 | |

| 103.5–113.5 | −6.12 | 77 | −6.69 | [−8.90; −4.54] | <.001 * | −0.69 | |

| 114–140.5 | −10.15 | 46 | −16.09 | [−19.15; −12.95] | <.001 * | −1.48 |

| Domain | Predictor | b | 95% CIb | β | 95% CIβ | sr² | 95% CIsr² | r | R² [95% CI] | ΔR² [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Step 1 | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 81.42 ** | [66.74, 95.86] | .061 ** | |||||||

| IQ | 0.26 ** | [0.13, 0.39] | .25 | [.12, .37] | .06 | [.02, .13] | .25 ** | [.02, .13] | ||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||

| (Intercept) | 39.01 | [−108.62, 220.43] | .063 ** | .002 | ||||||

| IQ | 1.05 | [−2.25, 3.85] | 1.02 | [−2.21, 3.63] | .00 | [.00, .04] | .25 ** | [.02, .16] | [.00, .04] | |

| IQ² | −0.00 | [−0.02, 0.01] | −.77 | [−3.38, 2.42] | .00 | [.00, .04] | .24 ** | |||

| Verbal | Step 1 | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 96.81 ** | [79.90, 112.15] | .010 | |||||||

| IQ | 0.11 | [−0.02, 0.26] | .10 | [−.02, .23] | .01 | [.00, .05] | .10 | [.00, .05] | ||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||

| (Intercept) | 197.07 ** | [68.37, 281.14] | .028 * | .018 * | ||||||

| IQ | −1.79 * | [−3.31, 0.54] | −1.63 | [−3.00, .46] | .02 | [.00, .05] | .10 | [.01, .07] | [.00, .06] | |

| IQ² | 0.01 * | [−0.00, 0.02] | 1.73 | [−.28, 3.12] | .02 | [.00, .06] | .11 | |||

| Numerical | Step 1 | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 61.24 ** | [48.65, 74.45] | .158 ** | |||||||

| IQ | 0.37 ** | [0.25, 0.48] | .40 | [.28, .50] | .16 | [.08, .25] | .40 ** | [.08, .25] | ||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||

| (Intercept) | 148.79 ** | [42.72, 268.27] | .173 ** | .015 * | ||||||

| IQ | −1.26 | [−3.43, 0.66] | −1.35 | [−3.70, .69] | .01 | [.00, .07] | .40 ** | [.11, .27] | [.00, .08] | |

| IQ² | 0.01 * | [−0.00, 0.02] | 1.75 | [−.25, 4.06] | .02 | [.00, .08] | .41 ** | |||

| Spatial | Step 1 | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 81.06 ** | [72.00, 90.31] | .085 ** | |||||||

| IQ | 0.21 ** | [0.12, 0.30] | .29 | [.17, .40] | .09 | [.03, .16] | .29 ** | [.03, .16] | ||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||

| (Intercept) | 72.94 ** | [18.86, 121.24] | .086 ** | .000 | ||||||

| IQ | 0.38 | [−0.58, 1.44] | .51 | [−.82, 1.96] | .00 | [.00, .03] | .29 ** | [.03, .17] | [.00, .02] | |

| IQ² | −0.00 | [−0.01, 0.00] | −.22 | [−1.67, 1.12] | .00 | [.00, .02] | .29 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hofer, G.; Mraulak, V.; Grinschgl, S.; Neubauer, A.C. Less-Intelligent and Unaware? Accuracy and Dunning–Kruger Effects for Self-Estimates of Different Aspects of Intelligence. J. Intell. 2022, 10, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10010010

Hofer G, Mraulak V, Grinschgl S, Neubauer AC. Less-Intelligent and Unaware? Accuracy and Dunning–Kruger Effects for Self-Estimates of Different Aspects of Intelligence. Journal of Intelligence. 2022; 10(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleHofer, Gabriela, Valentina Mraulak, Sandra Grinschgl, and Aljoscha C. Neubauer. 2022. "Less-Intelligent and Unaware? Accuracy and Dunning–Kruger Effects for Self-Estimates of Different Aspects of Intelligence" Journal of Intelligence 10, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10010010

APA StyleHofer, G., Mraulak, V., Grinschgl, S., & Neubauer, A. C. (2022). Less-Intelligent and Unaware? Accuracy and Dunning–Kruger Effects for Self-Estimates of Different Aspects of Intelligence. Journal of Intelligence, 10(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence10010010