However, in all the above cases, we generally do not have the reciprocal subset inclusion. This is what we will study for particular constraints.

2.2.1. Application to Thermodynamics

Assume first that the concentrations of the metabolites (resp., of the internal metabolites) are known and given. From Equations (

51) and (

52) and Lemma 1, we obtain

,

are thus flux cones and

,

flux polyhedra (possibly equal to

or empty (for polyhedra) if the flux directions imposed by the concentrations of the metabolites and by the second law of thermodynamics are incompatible with the steady-state assumption). When nonempty, they consist of a single flux tope. From Equation (

18), (

36) and (

39), it follows that

and the same for

and

. Now, considering the decomposition of

(resp.,

) into flux topes, we can proceed flux tope by flux tope for the computation of the sets above. Starting from a FT

(resp.,

), we have

(resp.,

) with

inf (where

inf is defined component-wise with

inf) and the four sets above are equal to ExVs (

), ExPs (

), ExVs (

) and EFMs (

) respectively. This is in particular the case if we split each reversible reaction into two irreversible ones as, in higher dimension,

(resp.,

) is reduced to a single flux tope defined by

, the all-positive sign vector, and thus

is obtained from

by changing each − into 0. Note also that

(resp.,

) consistent does not imply that

(resp.,

) is consistent (

being full support does not imply that

is full support).

Proposition 1. Given metabolite concentrations , the space of flux vectors in (resp., ) satisfying the thermodynamic constraint is a flux cone (resp., a flux polyhedron), made up of vectors of (resp., ) which conform to the thermodynamic sign vector given in Equation (44). Its elementary flux vectors, identical to elementary flux modes, (resp., elementary flux points, elementary flux vectors and elementary flux modes) are exactly those of (resp., FP) that satisfy the constraint, i.e., that conform to . The same result holds for internal metabolite concentrations and thermodynamic constraint with . Let us now consider the more usual case where the concentrations of the metabolites (at least those of internal metabolites) are unknown. From Equation (

45), we obtain one or the other form for the thermodynamic constraint (existentially quantified on metabolite concentrations):

Though the metabolite concentrations

are unknown, some lower bounds

and upper bounds

on these concentrations are often known. They are thus added as additional constraints:

The solution space in of these constraints is thus (idem for ) and (idem for ). From the result of Lemma 1, it follows that and (idem for and with ). This is obviously enough to take the union on the maximal ’s (resp., ’s) when varies. As these are at most , the union is finite.

Lemma 3. The set (resp., ) of vectors in satisfying the thermodynamic constraint (resp., ) is a union of closed orthants. More precisely, it is the (finite) union for all (resp., all bounded ) of the sets of vectors that conform to , i.e., ’s. The same result holds for and with M and .

It follows from Equations (

53), (

54), (

56) and (

57) that

and the same for

and

with

M and

, where all unions are finite.

From this and Equations (

18), (

36) and (

39), we get

and the analog for

,

and

. Now, considering the decomposition of

(resp.,

) into flux topes, we can proceed flux tope by flux tope for the computation of the sets above. Starting from a FT

(resp.,

), we have

(resp.,

) where

are the maximal sign vectors in {

inf and the four sets above are equal to

ExVs (

),

ExPs (

),

ExVs (

) and

EFMs (

), respectively. This is in particular the case if we split each reversible reaction into two irreversible ones as, in higher dimension,

(resp.,

) is reduced to a single flux tope defined by

. The analog holds for

,

and

.

Proposition 2. The space of flux vectors in (resp., ) satisfying the thermodynamic constraint , or , is a finite union of flux cones (resp., flux polyhedra), obtained as those vectors of (resp., ) which conform to , for a certain , or bounded . It is thus no longer convex but made up of particular faces (resp., ) of each flux tope for (resp., for ), with . Its elementary flux vectors, identical to elementary flux modes, (resp., elementary flux points, elementary flux vectors and elementary flux modes) are exactly those of (resp., FP) that satisfy the constraint, i.e., that conform to a certain , and coincide thus with the extreme vectors (resp., the extreme points, extreme vectors and elementary modes) of the ’s (resp., ’s). The same result holds for , or , with M and .

We will now refine this result in order to characterize the faces involved. Consider the case of a flux cone where the concentrations of external metabolites are given and assume first there are no bounds on the concentrations of the internal metabolites [

37]. As

and

, let us begin by studying

. We have

from Equation (

44). By applying the monotonic logarithm function and noting

the vector whose components are given by

, we obtain

. We will now make use of Gale’s theorem (or Kuhn–Fourier theorem), which is a form of Farkas’ duality lemma (for two vectors

,

,

means

for all

i):

Gale’s theorem (a form of Farkas’ lemma). For any and , exactly one of the following statements holds:

- (a)

there exists such that ;

- (b)

there exists such that , and .

Applying this theorem in the formula above to (where we note the subspace of vectors having a null component outside the support of ), given by , and , given by , provides where is defined by: .

We thus obtain

. This can be rewritten as

, where

is an open half-space with the hyperplane

as a frontier. Considering the decomposition of

into FTs

, this is equivalent to

for all

’s maximal sign vectors in

sign(

). Now, note that, in this formula,

is the minimal face (for set inclusion) of

containing

. We finally obtain finally:

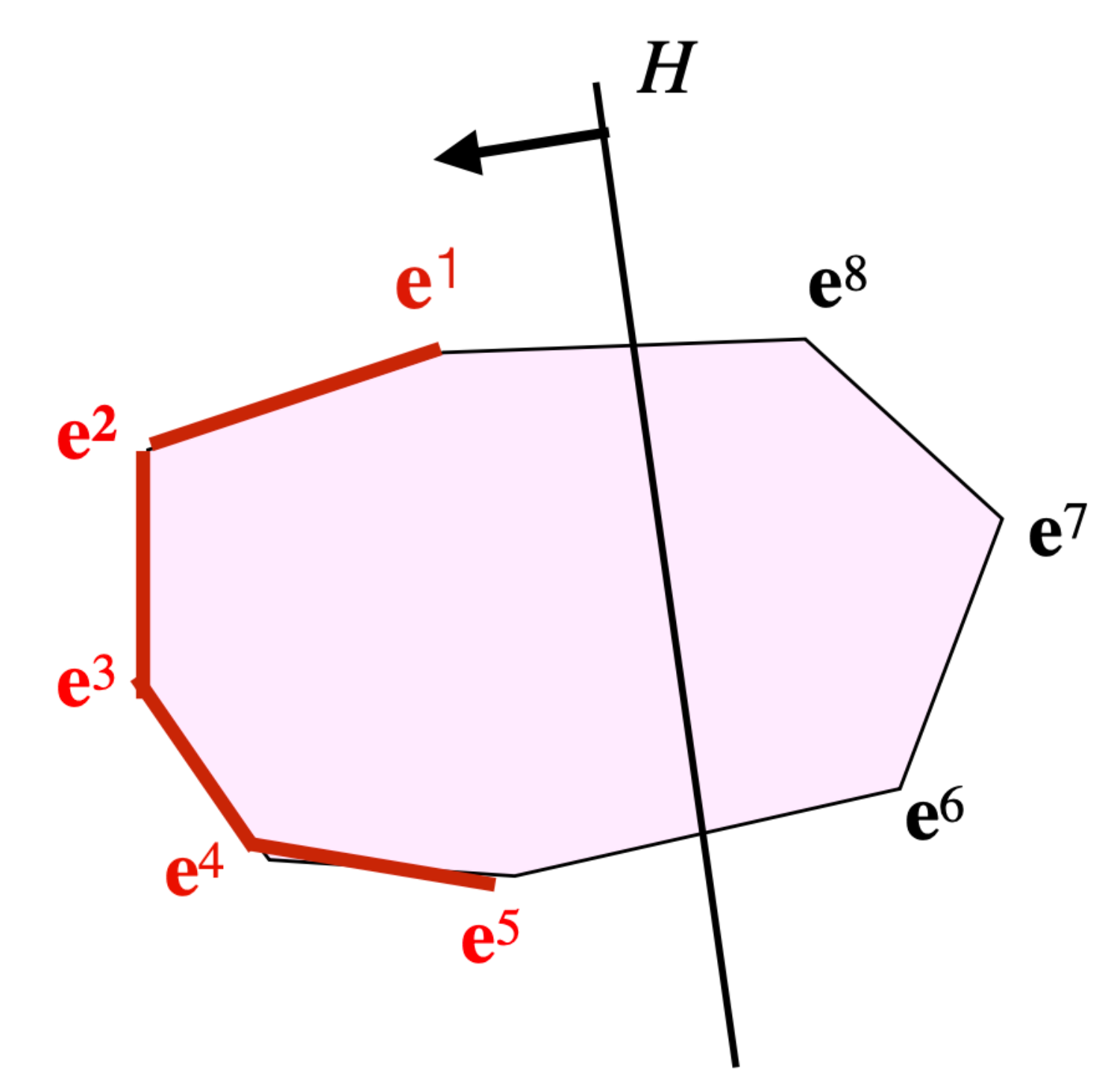

That is to say,

is the union of all the maximal faces

of the FTs for

such that

or, equivalently, the union of all maximal faces

of the

’s for all

r-orthants

O such that

(see

Figure 3).

A topological consequence of this characterization is that

is a connected set (actually arc-connected). Another consequence, regarding EFMs (or, equivalently, EFVs), is:

i.e., the elementary flux modes in the (non-convex) cone of those flux vectors in

satisfying the thermodynamic constraint

are exactly those elementary flux modes in

that satisfy

, i.e., that belong to the open half-space

. We can equivalently write

where

is the polyhedral cone obtained from

merely by adding the homogeneous linear inequality

[

38]. Each flux vector of

is a conformal conical sum of these EFMs, but the converse is false as

is not convex. Thus the set of EFMs, considered globally, does not characterize the solution space

. More precisely, we have

where

is as in Equation (

66), i.e.,

is characterized by the decomposition of the set of EFMs into the (non-disjoint) subsets

. Now, the

’s are exactly the maximal subsets of EFMs included in a given flux tope for

(i.e., in a given

r-orthant

O) and whose conical hull is included in

, i.e., all vectors in this hull must satisfy the constraint

:

maximal such that

EFMs

and

with

O r-orthant and

. Such an

is called a largest thermodynamically consistent set (LTCS) of EFMs [

39] in

O (or, equivalently, in the flux tope

defined by

O).

We could want to estimate the ratio of thermodynamically feasible EFMs on all EFMs, i.e., the ratio of EFMs on EFMs . If all reactions are reversible (), then the function maps the EFMs on one side of hyperplane onto the EFMs on the other side. Thus, if we neglect the EFMs that might belong to this hyperplane, it means that 50% of the EFMs are thermodynamically feasible (and thus only 50% eliminated). Now, intuitively, irreversible reactions given in come from an expert knowledge that can be seen as a form of compiled thermodynamic knowledge, as we saw that it is thermodynamics which imposes the direction in which a reaction may proceed. Therefore, we can assume, provided the adequacy of the model for some given environment (such as the concentrations of external metabolites, supposed here to be known), that any thermodynamically feasible EFM satisfies these irreversibility constraints. Under this assumption, the irreversibility constraints rule out only thermodynamically unfeasible EFMs so if we then apply the thermodynamic constraint we only eliminate at most than 50% of the remaining EFMs (from 50% when all reactions are reversible to 0% when all are irreversible, without splitting any reversible reaction into two irreversible ones).

If inhomogeneous linear constraints are added, we have

, with

Equation (

25) and we obtain in the same way, for all

’s maximal sign vectors in

sign(

)

That is to say, is the union of all the such that is a maximal face of a FT for verifying or, equivalently, the union of the for all maximal faces of the ’s for all r-orthants O such that . Take care because the ’s involved are faces of included in , but not any face of included in is included in (as such a face may be defined by inhomogeneous equality constraints coming from and not only by nullity constraints of the form ). is no longer a connected set in general.

We can sum up these results as follows.

Proposition 3. The space of flux vectors in satisfying the thermodynamic constraint is a finite union of flux cones, obtained as all the maximal faces of all the flux topes that are entirely contained (except the null vector) in the open half-space . The thermodynamically feasible EFMs are thus those EFMs which belong to this half-space and can be simply computed as the EFMs of the flux cone obtained from by adding to it the homogeneous linear inequality (and removing those EFMs that would belong to the frontier hyperplane of ). The set of these EFMs can be decomposed into (non-disjoint) maximal subsets of EFMs belonging to a same flux tope (i.e., a same r-orthant) and whose conical hull is made up of thermodynamically feasible vectors, each of these subsets thus representing the set of EFMs of one of the maximal faces above. At most 50% of the EFMs can thus be ruled out as thermodynamically infeasible, if we assume that no thermodynamically feasible flux vector violates given irreversibility constraints. In the presence of additional inhomogeneous linear constraints on flux vectors given by , the space of flux vectors in FP satisfying TC is a finite union of flux polyhedra, obtained as intersections of the flux cones above with the polyhedron defined by . All these results hold for constraint TC by just replacing the ’s by the ’s.

This applies in particular to and (after splitting each reversible reaction into two irreversible ones) with the simplification, as (resp., ) is reduced to a single flux tope defined by , that we must just consider the maximal faces of that are entirely contained (except the null vector) in the open half-space .

Consider now the case where certain bounds on the concentrations of internal metabolites are known, i.e., the case of the thermodynamic constraint

. We have

. From what precedes, we obtain

. Applying Gale’s theorem in this formula to

, with

, and

, with

, provides

where

is defined by

. Let

, where

and

.

is a flux cone in

of dimension

and

. We thus obtain

. This is equivalent to:

for all flux topes

for

. This can be rewritten as

, where we note

the open half-space with hyperplane

as a frontier. We have

and

. Now, note that, in the formula above,

is a face of the cone

(we note

the sign vector of dimension

obtained by concatenation of

of dimension

r and + of dimension

, thus

) whose intersection with

is equal to

, the minimal face of the tope

containing

. Actually, among all the faces of

whose intersection with

is equal to

, this is the maximal one (without any constraint on the

factor). Thus, finally,

.

Note that any

given by Equation (

71) is a face of a certain

given by Equation (

66) (i.e.,

).

is no longer a connected set in general. A consequence, for EFMs (or, equivalently, EFVs), is:

where

is the maximal face of

s.t.

. This means that the elementary flux modes in the (non-convex) cone of those flux vectors in

satisfying the thermodynamic constraint

are exactly those elementary flux modes

in

(or in

) that satisfy

, i.e., such that the maximal face of

whose intersection with

is equal to the ray

is included in

. Note that EFMs

is thus given by

Each flux vector of

is a conformal conical sum of these EFMs, but the converse is false as

is not convex. More precisely, we have

where

is as in Equation (

71), i.e.,

is characterized by the decomposition of the set of EFMs into the (non-disjoint) subsets

. Now, the

’s are exactly the maximal subsets of EFMs included in a given flux tope for

(i.e., in a given

r-orthant

O) and whose conical hull is included in

, i.e., all vectors in this hull must satisfy the constraint

:

maximal such that

EFMs

and

with

O r-orthant and

. Such an

is called a largest thermodynamically consistent (for bounded concentrations of internal metabolites) set (LTCbS) of EFMs [

39] in

O (or, equivalently, in the flux tope

defined by

O) and is included in a certain LTCS

as in Equation (

69).

If inhomogeneous linear constraints

are added, we have, for all

’s maximal sign vectors in

sign(

):

with

as in Equation (

71). That is to say,

is the union of all the

such that

is given as in Equation (

71).

We can sum up these results as follows.

Proposition 4. For a flux cone in , let us define its lift to as the flux cone . Thus, . For any flux tope for and any face of , its lift to is defined as the maximal face of whose intersection with is equal to . The space of flux vectors in satisfying the thermodynamic constraint is a finite union of flux cones, obtained as all the maximal faces of all the flux topes whose lifts to are entirely contained (except vectors from ) in the open half-space , where . The thermodynamically feasible EFMs in are those EFMs in whose lifts (as rays) are contained (except vectors from ) in this half-space. The set of these EFMs can be decomposed into (non-disjoint) maximal subsets of belonging to a same flux tope (i.e., a same r-orthant) and whose conical hull is made up of thermodynamically feasible vectors, each of these subsets representing thus the set of EFMs of one of the maximal faces above. In the presence of additional inhomogeneous linear constraints on flux vectors given by , the space of flux vectors in FP satisfying TCb is a finite union of flux polyhedra, obtained as intersections of the flux cones above with the polyhedron defined by .

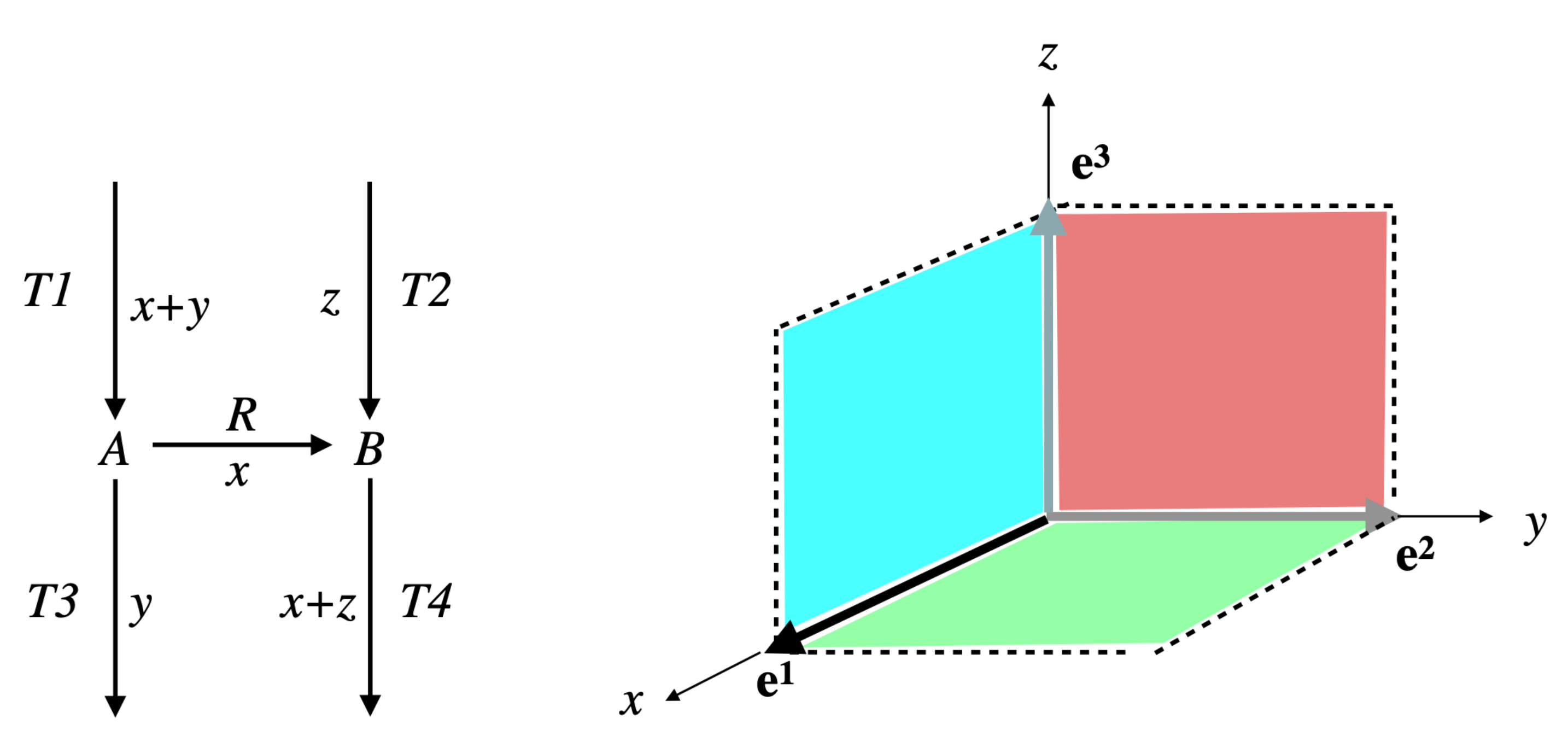

2.2.2. Application to Kinetics

In the same way, we obtain for the kinetic constraint in the absence of knowledge regarding values of concentrations of enzymes and metabolites:

Once more we can add optional lower and upper bounds

and

on metabolite concentrations and/or lower and upper bounds

and

on enzyme concentrations if they are known, and also a global enzymatic resource constraint, which is often considered, as

, where

is a constant positive vector of size

r and

W a positive constant:

We can also consider intermediate constraints, existentially quantified only on metabolite concentrations if enzyme concentrations are known:

possibly with bounds on metabolite concentrations in the quantification:

or only on enzyme concentrations if metabolite concentrations are known:

possibly with enzymatic resource constraint and bounds on enzyme concentrations in the quantification:

The solution space in of the constraint is , as the sign of is the thermodynamic sign vector . It is thus the same as the solution space of the thermodynamic constraint and is the closed orthant . It follows that the solution space of the constraint , given by , is the same as the solution space of the thermodynamic constraint and is the finite union of the closed orthants . Similarly, if the bounds are only on the metabolite concentrations, i.e., there are no bounds on enzyme concentrations. From , it follows that the flux vectors in are defined by the linear inequalities: for those i’s such that , for those i’s such that , for those i’s such that and . Thus is a convex polyhedron (a parallelepiped contained in the closed orthant , truncated by a hyperplane). Now, if , i.e., in the absence of positive lower bounds on enzyme concentrations, this polyhedron has as a vertex and is nothing else than , i.e., the closed orthant , truncated as a parallelepiped by the faces given by for those i’s such that and by the hyperplane . Consequently, is equal to a certain truncation of , defined as the finite union of truncations of the closed orthants (each becoming a parallelepiped, after being truncated by hyperplanes according to equations if (resp., if ), where (resp., ) applies to those such that , which gives a polyhedron, but also, in the presence of an enzymatic resource constraint, by an algebraic, nonlinear, surface, which gives in this case a local solution space in that is no longer a polyhedron and is not necessarily convex).

Proposition 5. Given metabolite concentrations , the kinetic constraint is identical to the thermodynamic constraint and thus the set of vectors in satisfying is the closed orthant defined by the thermodynamic sign vector . The kinetic constraint is identical to the thermodynamic constraint and thus the set of vectors in satisfying is a union of closed orthants. In the presence of bounds only on metabolite concentrations (and not on enzyme concentrations), the kinetic constraint is identical to the thermodynamic constraint and thus the set of vectors in satisfying is a union of closed orthants. Therefore, these kinetic constraints boil down to thermodynamic constraints and the results regarding the geometrical structure of the corresponding spaces of flux vectors and the characterization of elementary flux vectors (or elementary flux modes) given by Propositions 1–4 apply: in particular, is a flux cone and and are finite unions of flux cones. For a given and in the presence of bounds on enzyme concentrations, the set of vectors in satisfying is a convex polyhedron and is thus a flux polyhedron. In the particular case where positive lower bounds on enzyme concentrations are absent, is just the parallelepiped obtained by truncating the flux cone by hyperplanes originating from the upper bounds on enzyme concentrations and by a hyperplane originating from the enzymatic resource constraint and coincides thus with the said flux cone in a certain adequate neighborhood of , i.e., for sufficiently small values of the fluxes. In this case, is thus a truncation (by an algebraic surface) of and coincides with this union of flux cones in a certain adequate neighborhood of and the characterization of elementary flux vectors remains valid in this neighborhood. These results extend in the presence of additional inhomogeneous linear constraints on flux vectors given by by intersecting the solution spaces above with the polyhedron defined by , giving rise to flux polyhedra (results in a neighborhood of holding only if h < 0).

However, the geometric structure of , of and of in the presence of positive lower bounds on enzyme concentrations, depends on the kinetic function and , and are generally neither polyhedra nor convex.

Proposition 5 has important consequences on constrained enzyme allocation problems in kinetic metabolic networks. Considering a kinetic metabolic network, with possible bounds on metabolite concentrations, but not on enzyme concentrations, i.e., with solution space

, or

, which is a finite union, for

varying, of the flux cones

, the generic enzyme allocation problem consists in maximizing the specific flux (or specific rate, i.e., rate expressed per unit of biomass amount) of a given reaction, say

k, defined as

, where

is a flux vector in

or

and

denotes the total protein content in the system.

is expressed in all generality as a fixed weighted sum of the enzyme concentrations,

(the

’s being given positive weights that denote the fraction of the resource used per unit of enzyme), able to encode different enzymatic constraints (such as limited cellular or membrane surface space) as well as other constraints regarding the abundance of certain enzymes. Likewise, the steady-state flux component

may stand for diverse metabolic processes, ranging from the synthesis rate of a particular product within a specific pathway to the rate of overall cellular growth. The formation rate of a metabolic product expressed per gram of biomass and the specific growth rate of a cell are both examples of such specific rates. We look for maximization in the solution space by varying the metabolite concentrations (inside their bounds, if any) and the enzyme concentrations (without bounds), which gives rise to a complex non-convex optimization problem. Now, maximizing

is equivalent to fixing the rate

to a positive value, e.g., to 1, and minimizing the

needed to attain this level of

. This means minimizing the function

by varying

(with possible bounds) and, for each given

, the flux vector

in

(without bounds on

as we assume there are no bounds on enzyme concentrations). If all

’s are empty, the problem is unsolvable, i.e.,

is incompatible with the kinetics. Otherwise, i.e., when the problem is solvable, we consider successively each nonempty

. Such an

is a flux polyhedron whose elementary flux points (which are equal to the extreme points or vertices) correspond to the intersections of the hyperplane

with extreme rays (edges) of

, i.e., EFMs of

or

, and whose elementary vectors (equal to extreme vectors), if any, correspond to the extreme rays of

. As, for

fixed, the function to minimize is linear in

, its minimum on

is reached on a lower-dimensional face of

(as

,

and

is included in a closed orthant, this face is necessarily a convex hull of certain extreme points of

even if it is not a polytope, i.e., no extreme vector may occur as one of the generators of this face), and thus reached in particular at at least one extreme point, i.e., at an EFM. Now, as the total number of EFMs is finite, so is the number of those for which the minimum of the function occurs for any given

, considering all nonempty

’s. Therefore, when

varies in its domain, we obtain the result that the maximum of the specific flux

occurs (at least) at an EFM of

or

. In the case of

and assuming the

’s are continuous, this maximum is attained at an EFM at finite metabolite concentrations as

then varies in the compact set

. In the case of

, the maximum might not be attained at finite metabolite concentrations. This is the result already obtained in [

40,

41] and we followed a similar proof, but relying this time on a precise characterization of the solution space

or

and of the EFMs given by the Proposition 5, which was not the case in the above-quoted works. Finally, the enzyme allocation problem can theoretically be solved by computing all the thermodynamically feasible EFMs having

k in their support (i.e., satisfying the Boolean constraint

, see next subsection), say

(all components of which are fixed by

), and, for each one, by computing the minimum (if it exists) of

for

varying in its domain, such that

for all

, which is a much simpler optimization problem than the initial one. The global minimum, if it exists, is then the smallest of these local minima, for all

’s. We then obtain the maximum value of the specific flux

, an EFM where this maximum occurs and the values of the metabolite concentrations for which it occurs.

Proposition 6. Given a kinetic metabolic network with possible bounds on metabolite concentrations, but not on enzyme concentrations, i.e., with solution space or , if the enzyme allocation problem, which consists in maximizing the specific flux (rate per unit of biomass amount) in a given reaction k, i.e., , where is a flux vector in or and is the total protein content in the system (the ’s being fixed positive weights), has an optimal solution (which is always the case for if the problem is solvable), then this solution is reached in particular at an EFM of or .

2.2.3. Application to Regulatory Constraints

From Lemma 2, we obtain that (resp., ) is the disjoint union of ’s (resp., ’s), for certain open orthants and, after merging, the disjoint union of ’s (resp., ’s), for certain semi-open orthants (orthants without some of their faces), without any further merging possible.

We will call open polyhedral cone (resp., open polyhedron) in dimension

an

r-polyhedral cone

C (resp.,

r-polyhedron

P) without its facets, and we will note it

(resp.,

) as it coincides with the topological interior of

C (resp.,

P) in the affine span of

C (resp.,

P). Reciprocally,

C (resp.,

P) is the topological closure of

(resp.,

) in

.

(resp.,

) is defined as in Equation (

7) (resp., in Equation (

26)) but with strict inequalities (and equalities for defining its affine space). We will in particular consider open faces of a cone

C or polyhedron

P as

for

F a face of

C or

P.

C (resp.,

P) is the disjoint union of its open faces (by convention, a face of dimension 0, i.e., a vertex, is equal to its open face).

It follows from these definitions that, for any closed r-orthant O and any open orthant , (resp., ) is an open face of (resp., a disjoint union of open faces of , as we have to keep faces corresponding to ). In all, we obtain that

(resp., ) is a disjoint union of open faces of the flux cone (resp., the flux polyhedron ) or, equivalently, that, for any flux tope FC&η for FC(resp., FP&η for FP), (resp., ) is a disjoint union of open faces of FC&η (resp., FP&η). As we grouped together open orthants into semi-open orthants in Lemma 2, we can also group together with such an open face

all those other open faces in question where is a face of F to obtain thus a (minimal) disjoint union of semi-open polyhedral cones (resp., semi-open polyhedra). Here, we call semi-open polyhedral cone (resp., semi-open polyhedron a polyhedral cone C (resp., polyhedron P) without certain (between zero and all) of its faces of lesser dimension, that can be thus expressed as a disjoint union of certain (between all and only , resp.,) of the open faces of C (resp., P). We have: , resp., ).

Proposition 7. Given an arbitrary Boolean constraint Bc, the solution space (resp., ) for the regulatory constraint is a finite disjoint union of open polyhedral cones (resp., open polyhedra), which are certain open faces of all the flux topes (resp., ). Grouping together certain of these open faces according to Lemma 2, we obtain a disjoint union of semi-open (i.e., without certain of their faces of lesser dimension) faces of the ’s (resp., ’s), without any possible further merging of two of them to make up a bigger semi-open face.

Note that the rules presented in the proof of Lemma 2 to group together open faces into semi-open faces are applied globally to all flux topes. If we choose to apply them separately for each flux tope, then the union of semi-open faces obtained is no longer disjoint in general as two such semi-open faces for two different flux topes may have a nonempty intersection (as (resp., ) and (resp., ), for two different closed r-orthants O and O′ may have open faces in common). Note also that, even after this merging, there may exist a strict inclusion relationship between the closures of two semi-open faces.

From this geometrical structure of the solution space, we will now deduce what its EFMs and its EFVs (or EFPs) are. Let us begin with a preliminary remark. We know that, by definition of EFVs, we have, for a flux cone , EFVs EFVs (and idem for a flux polyhedron with EFPs and EFVs), which remains true for any constrained flux cone subset (or constrained flux polyhedron subset ) whatever the biological constraint is. We saw that this equality was also satisfied by EFMs for : EFMs EFMs (and idem for ) and remained true for for any thermodynamic constraint or any kinetic constraint of the form , or (in the absence of bounds on enzyme concentrations), thus allowing in these cases to decompose the identification of EFMs flux tope by flux tope, as for EFVs. However this is no longer true for regulatory constraints. Actually, counter-examples can be found in the presence of reversible reactions, used in a given direction in an EFM local to a certain flux tope and in the other direction in an EFM local to another flux tope, choosing the Boolean constraint such that it imposes a strict set inclusion between the supports of these two local EFMs.

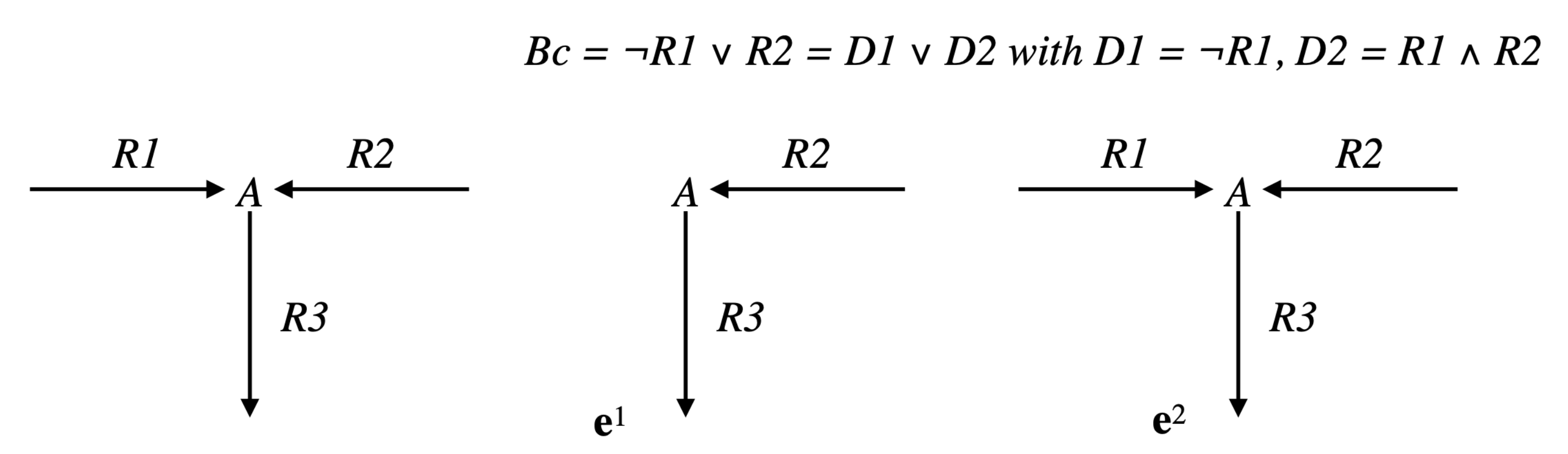

Example 1. Consider the simple network comprising one reaction , where A and B are the two internal metabolites, and four transfer reactions , , , , and assume that R and are reversible (we will note par rev() the reversed reaction), the three other reactions being irreversible (see Figure 4). It is obvious that , made up of , , made up of , and , made up of , are EFMs of . Consider now the Boolean constraint . Then, is an EFM of , belonging to . Moreover, any with is an EFM of (obviously, the sub-pathways and of do not belong to ). As and , we have and thus is not an EFM of . Now, from a biological point of view, it is not relevant to compare supports of two pathways with a certain reaction in a given direction in the first support and in the other direction in the second support (case of R and in the example). This means that the useful concept concerning minimality is not support-minimality, but sign-minimality (exactly in the same way as, concerning decomposition, we saw that the useful concept is not non-decomposability but conform non-decomposability), which is equivalent to comparing supports separately for each closed r-orthant, i.e., for each flux tope. We will thus identify the EFMs flux tope by flux tope (note that this is analog to distinguishing a positive flux from a negative flux in a regulatory constraint, e.g., distinguishing the constraints and in the example above, which could be done by adopting a tri-valued logic instead of a Boolean logic to represent these constraints; this is obviously done automatically when splitting each reversible reaction into two irreversible ones, where only the positive r-orthant has to be considered).

Therefore, we will consider in the following an arbitrary closed

r-orthant

O given by a full support sign vector

(with

for

) and consider the part of the solution space limited to this orthant, i.e.,

(resp.,

), thus we can limit ourselves to sign vectors

that are maximal in

(resp.,

). We saw that we could rewrite the Boolean constraint as a disjunction of two by two exclusive disjuncts,

, decomposing thus the solution space

(resp.,

) into the disjoint solution spaces for each disjunct,

(resp.,

). The elementary flux vectors (i.e., faces of dimension one) of

that satisfy the constraint

are obviously elementary flux vectors of

and the reciprocal is also true: if a flux vector of the semi-open polyhedral cone

is not an elementary flux vector of

, i.e., is not a face of dimension one, then it belongs to the interior of a face of

of dimension at least two and is thus conformally decomposable in this face, i.e., is not elementary in

. It follows that the elementary flux vectors of

are made up of all the elementary flux vectors of the

’s. We can sum up the results regarding EFVs as:

This means that EFVs can be computed flux tope by flux tope and constraint-disjunct by constraint-disjunct. Moreover, the result holds also for EFPs (by considering vertices of ) and EFVs of .

However, for EFMs, we have to take care that a phenomenon similar to that described in the example above still arises and that, even in a given flux tope, an EFM of is not necessarily an EFM of .

Example 2. Consider the network comprising three irreversible reactions and one internal metabolite A: , , , and the Boolean constraint , decomposed as , with and (see Figure 5). Take . Then, , made up of , which is the only EFM of , is also the only EFM of . However any with , made up of , is an EFM of and is not an EFM of . Note that the way the constraint is decomposed matters. With the decomposition with and , the result for is identical to that for , but . This means that, if it is natural to study each

(resp.,

) separately in order to characterize the solution space and if EFVs are obtained in this way by collecting all the local EFVs, it is not the case for EFMs and, after collecting all local EFMs, we must only keep those with minimal support:

Proposition 8. Given an arbitrary regulatory constraint with , where the disjuncts are taken two by two inconsistent, and the associated constrained flux cone subset (resp., constrained flux polyhedron subset ), its EFVs (resp., EFPs and EFVs) are obtained by collecting these for each flux tope (i.e., in each r-orthant ) and for each disjunct, i.e., for each (resp., ), and are nothing else than the EFVs (resp., EFPs and EFVs) of (resp., ) satisfying the constraint . This is not the case for EFMs. First, an EFM of is not necessarily an EFM of , but actually the biologically relevant minimality concept being sign-minimality and not support-minimality, we will consider EFMs for each flux tope . Second, an EFM of is not necessarily an EFM of . EFMs of are actually obtained by collecting EFMs of for all k and keeping only those with minimal support.

This being said, we will now focus on an arbitrary disjunct

D of the form

with

. Thus,

(resp.,

) is the semi-open face

of

(resp.,

), obtained from the face

F defined by

(i.e.,

, idem with

) by removing its facets

for all

. Let’s note EFMs

EFMs

those EFMs of

that satisfy the constraint

and EFMs

EFMs

the EFMs of the part of the solution space in

. Obviously, EFMs

EFMs

. If

,

and EFMs

EFMs

, so we will consider the case

. In this case, and contrary to what happens for thermodynamic and kinetic (as described in Proposition 5) constraints, there is generally no longer identity between EFMs

and EFMs

[

42].

Example 3. Consider the network of Example 1 (thus ) and let and be the EFM of made up of and . Then, for any , , positive conformal combination of the two EFMs and of , has support and belongs to (see Figure 6). EFMs correspond to the faces of dimension one (edges or extreme rays), if any, of the semi-open face , i.e., the edges of the face F that have not been removed, which means that they are not included in any hyperplane of equation , for a certain , or equivalently that their supports contain I. Now, consider a face of F, of dimension at least two, such that but no facet of has its interior included in (i.e., any facet of is included in an hyperplane of equation , for a certain ), if any. Note that several such may exist, but none can be included in another one, i.e., they are not comparable for inclusion in the lattice of the faces of F. Then, all vectors of have the same minimal support, i.e., EFMs EFMs . If (with ) are representatives of the extreme vectors of , we have (which is actually the same as as we are in orthant ) and thus and the common minimal support of all vectors of is . Conversely, if EFMs , let be the minimal face of F containing . If has dimension one (extreme ray), then and EFMs . If has dimension at least two, then no facet of has its interior included in , because if it were the case for one facet, then any vector of its interior would have its support strictly included in the support of , which would contradict the minimality of the latter. Finally, and all vectors of have the same support as and belong to EFMs EFMs . We have thus characterized both EFMs and EFMs EFMs . We stipulate now, for the latter one, the decomposition of its vectors into EFMs EFMs , in order to compute their supports, which is generally the only useful information (the precise decomposition into fluxes not often being very relevant). Therefore, we consider a face of F, of dimension at least two, such that but no facet of has its interior included in and a minimal set of vectors in EFMs such that . Note that, for any k, (and, as we have seen, ), because if for a certain we had , then would belong to all hyperplanes of equation for , thus to all facets of , which is impossible for a non-null vector. Let us note and, for any k, , . Then, for any k, , because if for a certain we had , then the vectors of would verify the constraint and have their supports included in , thus equal to it as it is minimal for vectors in , which would contradict the minimality of . Finally, as by construction and for , we obtain that constitutes a partition of I and is a set of vectors in EFMs EFMs EFMs such that by construction and for any , otherwise, by the same reasoning as above, could be suppressed from the set , contradicting its minimality. Finally, we obtain that the support of any vector in EFMs EFMs can be written as , where , , are vectors in EFMs verifying and for all k and , where is a partition of I (note that we have the same result for EFMs by taking ). Now, a given is not necessarily minimal among the whole collection when we vary and . It is also possible that it strictly contains the support of a vector in EFMs . Therefore, to obtain exactly the supports of vectors in EFMs EFMs , we must only keep the minimal elements for inclusion w.r.t. the whole collection extended by EFMs .

Example 4. Let us continue with the network of Examples 1 and 3, so and . We have and (see Figure 4). The only partition of with a size is given by: and . The only vector in whose support contains and not is and the only one whose support contains and not is . Thus, . Actually, we have from Example 3: (see Figure 6). Consider now the following network comprising two internal metabolites and seven irreversible reactions, six of which are transfer reactions, , , , , , , (see Figure 7). Let and . Let made up of , made up of , made up of , made up of , made up of , made up of , made up of and made up of . We have and . The only partition of with a size is given by and . The vectors in whose support contains and not are and and those whose support contains and not are and . We have , , and . Each one of the four supports obtained is minimal in this collection, but the first three contain . Thus, . Actually, . Finally, consider another network comprising three internal metabolites and seven irreversible reactions, five of which are transfer reactions, , , , , , , . Let and (see Figure 8). Let made up of , made up of , made up of , made up of , made up of and made up of . We have and . There are four partitions of with a size . The partition gives nothing because there is no vector in whose support contains but neither nor . For the partition and , the vector in whose support contains and not is and those whose support contains and not are , and , providing , and . For the partition and , the vector in whose support contains and not is and those whose support contains and not are , and , providing , and . For the partition and , the vector in whose support contains and not is and those whose support contains and not are and , providing and . The minimal elements of this collection of supports are , and . Minimizing also w.r.t. gives thus . Actually, . We have thus proved the following result.

Proposition 9. Given a Boolean constraint D as a conjunction of literals and an arbitrary closed r-orthant , let be the constrained flux cone subset for the regulatory constraint in . Let F be the face of the flux cone defined as , then is the semi-open flux cone obtained from F by removing its facets for all . Let be the EFMs of that satisfy and be the EFMs of . We get but, unlike the case of thermodynamic and kinetic (as in Proposition 5) constraints, there is generally no longer identity between and . correspond to the extreme rays (faces of dimension one) of , i.e., the edges of F whose support contains I. are the vectors of the ’s for all faces of F of dimension at least two, such that (i.e., is not included in any hyperplane with ) but no facet of has its interior included in (i.e., any facet of is included in a certain hyperplane with ). The supports of those vectors in are obtained as , where , , are vectors in verifying and for all k and , where is a partition of I (they are actually the minimal elements, for subset inclusion and including the supports of when checking minimality, obtained like this, for any partition of I, of size at least two, and any choice of as above).

This characterization of EFMs for flux cones in the presence of regulatory constraints does not hold as simply for flux polyhedra, because the added inhomogeneous linear constraints , given by , may not respect the structure of at all and may cut the interior of flux cones; we already mentioned that there is no direct relationship between EFMs and extreme or elementary fluxes for a flux polyhedron. Nevertheless, the ideas developed above for flux cones can be applied to flux polyhedra , where certain of their faces have to be removed due to the constraint D because they are included in certain hyperplanes {vi = 0}, in order to determine \. Moreover, in practice, ILC is generally only used to bound (below and/or above) fluxes, in which case each extreme ray of is still partly present in as for example an edge [α−,α+]e, defined by the two vertices α−e and α+e. The results above can then be transposed by using convex-conformal decomposition into vertices and conformal decomposition into elementary vectors to characterize \.

We are now interested in looking for vectors in the solution space that are (in some sense) non-decomposable while not being support-minimal, and in characterizing them, if any. We could think of EFVs (or EFPs) but, from the study above regarding EFMs, we note that, for a flux cone constrained by the regulatory constraint

D, the vectors in EFMs

EFMs

are necessarily conformally decomposable, as they can be described as the interiors of polyhedral cones in

of dimension at least two (for example,

in Example 3 can be decomposed as

). More straightforwardly, we can notice that EFMs

is equal to EFVs

, i.e., precisely the conformally non-decomposable vectors. As already pointed out, what matters more than the precise decomposition into fluxes is the decomposition of the supports (in the decomposition above of

, the supports of the components are unchanged, i.e., equal to

). It follows that a relevant concept for a solution vector is not to be conformally non-decomposable but, less strictly, to be (conformally) support-wise non-decomposable, in the sense that the vector cannot be conformally decomposed into two vectors of different (necessarily not greater) supports. Now, for all faces

of

F of dimension at least two such that

, not covered by Proposition 9, i.e., owning at least one facet

with interior included in

, it so happens that all vectors of

are actually support-wise decomposable, as each such vector can always be decomposed into a vector of

of same support and into a vector of

of smaller support. Therefore, in the decomposition, we do not authorize the same support for one of the component vectors. Thus the really relevant (less strict) concept is that the vector cannot be conformally decomposed into two vectors of smaller supports and we call a nonzero vector

of a convex polyhedral cone

C as (conformally) support-wise non-strictly-decomposable, if

The (conformally) support-wise non-strictly-decomposable vectors in

C (resp., flux vectors in a flux cone

) will be noted swNSDVs (resp., swNSDFVs). Note that we could have defined support-wise non-strictly decomposability more generally without imposing a conformal decomposition, but, as already pointed out, this is not relevant for biological fluxes and we will only use this concept in a certain tope. It is obvious that, in such a tope (resp., flux tope), EMs, ExVs = EVs ⊆ swNSDVs (resp., ExVs = EFVs = EFMs = swNSDFVs, so that all four definitions coincide). We will introduce a similar definition with a convex combination for a polyhedron

P (the previous definition and the associated relationships above being valid for its recession cone

). A vector

of a polyhedron

P is called support-wise convex(-conformally) non-strictly-decomposable, if

The support-wise convex(-conformally) non-strictly-decomposable vectors in P (resp., flux vectors in a flux polyhedron ) will be called support-wise non-strictly-decomposable points (resp., support-wise non-strictly-decomposable flux points) and noted swNSDPs (resp., swNSDFPs). It is obvious that, in any given tope (resp., flux tope), EMs, ExPs = EPs ⊆ swNSDPs (resp., EFMs, ExPs = EFPs ⊆ swNSDFPs).

With the notations of Proposition 9, let swNSDFVs swNSDFVs and swNSDFVs swNSDFVs . We have thus EFMs swNSDFVs EFMs swNSDFVs but, unlike the case of thermodynamic and kinetic (as in Proposition 5) constraints for flux cones, not only there is no longer identity between swNSDFVs and swNSDFVs (consequence of the non-identity between EFMs and EFMs ), but we will now see that there is generally no longer identity between EFMs and swNSDFVs .

Example 5. Continuing with the network of Example 3, . More precisely, we have (by considering only a representative for each ray) (see Figure 9). Therefore, we extend the results of Proposition 9 by refining the structure in F of swNSDFVs . Let be representatives of the extreme vectors of F, thus . We get the following structure for regarding EFMs and swNSDFVs, given in the form of an algorithm.

Let . Then EFMs . Note that R can vary from ∅ to M, thus EFMs from ∅ to EFMs . If , then EFMs EFMs swNSDFVs EFMs and the analysis is done (if has been chosen maximal in , this case corresponds to ). We consider the case here below.

Let us consider successively all faces of F of dimension at least two, such that , i.e., is not included in any hyperplane with (the lattice of faces of F can be explored for example in a way such that a sub-face is visited before a super-face; once such an has been found, all faces of F containing it are also suitable). Let , with , be representatives of the extreme vectors of . Thus, and . For each of these , three exclusive cases can now be distinguished.

If no facet of has its interior included in , i.e., any facet of is included in a certain hyperplane with (a necessary but insufficient condition is ), then EFMs EFMs and is a minimal support for vectors in .

If exactly one facet of has its interior included in , i.e., it is the only facet not included in any hyperplane with , then swNSDFVs EFMs and is a non-strictly-decomposable non-minimal support for vectors in (non-strictly-decomposable support means that any vector which is a conical sum of the ’s having this support is support-wise non-strictly-decomposable, independently of the choice of the non-negative coefficients fixing the contribution of each in the distribution of the fluxes). This result follows immediately from the facts that one facet is not enough to decompose a certain vector in strictly in terms of supports and that the support of the vectors in the interior of the facet in question is strictly included in the support of the vectors in .

If at least two facets of have their interior included in , i.e., these facets are not included in any hyperplane with , then let , with , be representatives of the extreme vectors of all these facets (note that we have then necessarily , i.e., ). Thus, the strict conical sum of the interiors of these facets, which is equal to , is not empty in (as there are at least two such facets) and is made up of the support-wise strictly-decomposable vectors of (by construction): swNSDFVs . Two subcases must therefore be distinguished.

If , i.e., the strict conical sum of the interiors of these facets is equal to , then swNSDFVs and is a strictly-decomposable support for vectors in (which means that any vector which is a conical sum of the ’s having this support is support-wise strictly-decomposable, independently of the choice of the non-negative coefficients fixing the contribution of each in the distribution of the fluxes).

If , then is split into two nonempty subsets: swNSDFVs and swNSDFV EFMs (note that is made up of the vectors of the conical decomposition of which on the ’s requires at least one with ). This means that part of the vectors of are support-wise non-strictly-decomposable and part are support-wise strictly-decomposable, while having the same non-minimal support (still equal to ). This proves that support-wise strict decomposability generally depends not only on the support, but also on the positive values of the fluxes and that, unlike the particular cases above, we cannot speak of a strictly-decomposable or non-strictly-decomposable support. Note that, in this subcase, the support-wise non-strictly-decomposable vectors of constitute the complementary, in the open cone , of the open sub-cone which is thus a finite disjoint union of semi-open cones, each of which is conically generated (with positive or non-negative coefficients according to faces that are present or not) by extreme vectors ’s with either or , thus in any case with , i.e., by extreme vectors EFMs EFMs .

We have finally proved the following result (keeping the notations of Proposition 9).

Proposition 10. Let be the support-wise non-strictly-decomposable vectors of . We obtain but, unlike the case of thermodynamic and kinetic (as in Proposition 5) constraints, there is in general no longer identity between and . Consider all faces of F of dimension at least two, such that (i.e., is not included in any hyperplane with ), and let . Result of Proposition 9 can be stated as . Now, we have . Note that the ’s considered here necessarily own at least one facet that is not included in any hyperplane with . There are actually two cases: For those ’s which own exactly one such facet (thus ), we obtain and the common support of vectors in is thus a non-strictly-decomposable (independently of the choice of the distribution of the fluxes) non-minimal support for vectors in . For those ’s which own at least two such facets , we obtain and , thus part of the vectors of (consisting of a finite disjoint union of semi-open cones) are support-wise non-strictly-decomposable and part (consisting of an open cone) are support-wise strictly-decomposable (depending on the choice of the distribution of the fluxes), while having the same non-minimal support.

Example 6. Let us continue with the network of Examples 3 and 5 (see Figure 9). is a pointed cone of dimension 3 included in the positive orthant of with axes in this order. We have . has 3 extreme rays (EFMs seen above) and 3 facets (see Figure 10). When we add the Boolean constraint , then and the solution space is the semi-open cone , i.e., F without its two edges corresponding to and . The only edge remaining in provides with support . There are three faces of F of dimension two with their interiors included in : , and . is the only one to have no facet with its interior included in , i.e., such that , thus . This means that the new EFMs that appear are all the positive combinations of and , all with the same minimal support . Regarding and , they both have as their only facet with interior included in , thus and and are both included in . and are thus non-strictly-decomposable (independently of the respective values of the fluxes in and or in and , respectively) non-minimal supports. The last face of F with its interior included in is F itself, of dimension three, with . As all the facets of F have their interior included in , we obtain . Thus, the pathways with nonzero fluxes in all five reactions, i.e., with support , are exactly the support-wise strictly-decomposable ones. Example 7. Let us consider the simple network comprising one reaction , where A and B are the two internal metabolites, and four transfer reactions , , , , and assume the five reactions irreversible (see Figure 11). is a pointed cone of dimension 3 included in the positive orthant of with axes in this order. We have: . has 4 facets and 4 extreme rays. Representatives of these extreme rays () are , , and , defined by their supports: , , and , respectively. Let us consider the Boolean constraint . Then, and the solution space is the semi-open cone , i.e., F without its two facets and .

The only EFM still present in is , thus with support .

There are two faces of F of dimension two with their interiors included in : and , both with as their only facet with interior included in . Thus, , , EFMs and . and are thus non-strictly-decomposable (independently of the respective values of the fluxes in and or in and , respectively) non-minimal supports.

The last face of F with its interior included in is F itself, of dimension three, with defined in by . F has exactly two facets with their interiors included in , namely, and and thus . The support-wise strictly-decomposable vectors constitute the open sub-cone of defined by : . They are the pathways of support such that the flux in is smaller than the flux in ; actually any vector with can be decomposed as , with arbitrary k, , i.e., into two support-wise non-strictly-decomposable vectors respectively in with support and in with support .

We thus have . The support-wise non-strictly-decomposable vectors constitute the semi-open sub-cone of defined by : . They are the pathways of support such that the flux in is not smaller than the flux in . Any vector with is equal to and belongs to if and to if .

However, in the case of a general constraint , take care that, if the support-wise strictly-decomposable vectors of each are support-wise strictly-decomposable in , it is not true for support-wise non-strictly-decomposable vectors and some of them for may be decomposable in .

This characterization of support-wise non-strictly-decomposable vectors in the presence of regulatory constraints does not extend directly from flux cones to flux polyhedra. The reason is that, due to inhomogeneous linear constraints , certain faces of are not defined by equalities of the form and thus play no role in the definition of the support of the vectors they contain. Consequently, the basis of the reasoning above, namely, that the support of vectors of the interior of any face is larger than the supports of vectors of the interior of any facet of this face, does not hold. Nevertheless, the ideas developed for flux cones for dealing with faces included in a certain hyperplane with , and thus removed from the solution space due to the Boolean constraint considered, can be applied. However, it is necessary at each step, when considering an arbitrary face, to distinguish its facets resulting from , not involved in the definition of the support, its facets included in a certain hyperplane with that are still present and contribute to the definition of the support, and its facets included in a certain hyperplane with that are removed.